User login

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma presenting as retinal hemorrhage

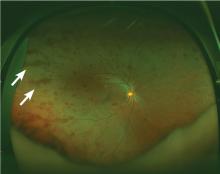

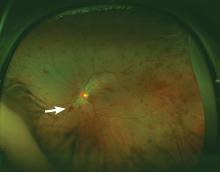

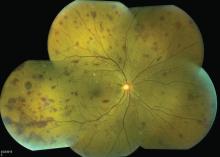

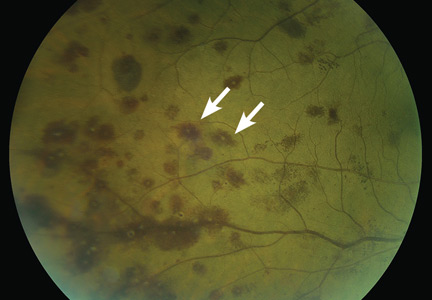

A 51-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to her primary care physician because of blurred vision, increased fatigue, palpitations, and intermittent episodes of epistaxis. Vital signs were within normal limits except for a heart rate of 110 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed pale conjunctivae and bilateral white-centered retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms

(Figures 1–4).

The results of laboratory studies:

- Hemoglobin 2.4 g/dL (reference range 12–16)

- Platelet count 78 × 109/L (150–400)

- White blood cell count 4.0 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Atypical lymphocytes 18% (0.0–3.0%)

- Reticulocyte index 0.3 (0.5–2.5%)

- Gamma gap 7.0 g/dL (< 4)

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) 5,560 mg/dL (61–356).

Bone marrow biopsy study showed complete effacement of the hematopoietic elements of normal marrow, and the diagnosis of B cell lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was made. Serum electrophoresis showed an elevated kappa-to-lambda ratio of 4.6500 (reference range 0.2600–1.6500). B cells expressed monotypic kappa surface immunoglobulin light chains CD19, CD20, and CD22. They did not express CD5. No testing was done for the MYD88 point mutation.

ROTH SPOTS

White-centered retinal hemorrhages, or Roth spots, are the result of rupture of retinal vessels with subsequent accumulation of platelets and fibrin surrounded by blood.1 Although Roth spots are mistakenly believed to be caused only by infective endocarditis, they are seen in a variety of conditions, including leukemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypoxia. Each of these conditions has a different mechanism for vessel rupture, which can include fragility of the smooth muscle vessel wall from hypoxemia and increased hydrostatic pressure in hyperviscosity syndrome.

Hypergammaglobulinemia is the most common cause of hyperviscosity syndrome and is usually associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, a type of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with the largest immunoglobulin, IgM. However, our patient presented with a variant of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with high levels of IgA, a small molecule that in high quantities can also cause hyperviscosity.

Immediate treatment is aimed at decreasing blood viscosity with plasmapheresis and controlling the underlying disease with chemotherapy.2 There have been cases of cancer-related Roth spots, in which the lesions disappeared after chemotherapy.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ROTH SPOTS

Roth spots share morphologic features with other retinal abnormalities such as “cotton wool” spots, Purtscher retinopathy, and cytomegalovirus retinitis. A thorough history and careful ophthalmologic examination can help differentiate these from Roth spots.

Cotton wool spots are a nonspecific sign of vascular insufficiency and represent an ischemic, inflammatory, or infectious condition or an embolic or neoplastic process. Most often, they represent retinopathy from poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On funduscopic examination, cotton wool spots are small, irregularly shaped, yellow-white plaques that may appear raised. They are often found over the posterior pole of the fundus. In contrast, Roth spots appear white or pale on a background of hemorrhage.

Purtscher retinopathy. Polygonal retinal whitening with sharp demarcation against the normal retina is pathognomonic of Purtscher retinopathy.4 Purtscher lesions may represent a traumatic or nontraumatic condition, including closed head injury, barotrauma, pancreatic disorder, connective tissue disease, fat embolism after long bone fracture, and even microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Patients usually describe diminished visual acuity in the context of injury or other systemic illness.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis is an important consideration in the immunocompromised patient presenting with retinal hemorrhage and is the most common cause of blindness in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).5 It is a slowly progressive disease, initially asymptomatic and involving one eye, but in some untreated patients with AIDS it may progress to the contralateral eye. When it progresses, patients usually present with floaters or vision loss. The retina can have cotton wool spots with a more diffuse pattern of hemorrhage on the periphery and white sheathing along blood vessels, eloquently described as “frosted branch angiitis.”

Our patient’s lesions appeared more punctate, in contrast to the often fulminant hemorrhagic necrosis or perivascular white lesions surrounding retinal vessels characteristic of cytomegalovirus retinitis.

THE NEED FOR ACTION

New-onset blurred vision should prompt a comprehensive history and physical examination, as it may be secondary to a life-threatening systemic disease. A thorough funduscopic examination may provide vital information and guide management and expeditious referrals for patients with time-sensitive conditions such as cancer.

Our patient decided to undergo treatment outside our hospital and so was lost to follow-up.

- Ling R, James B. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (Roth spots). Postgrad Med J 1998; 74:581–582.

- Mehta J, Singhal S. Hyperviscosity syndrome in plasma cell dyscrasias. Semin Thromb Hemost 2003; 29:467–471.

- Docherty SM, Reza M, Turner G, Bowles K. Resolution of Roth spots in chronic myeloid leukaemia after treatment with imatinib. Br J Haematol 2015; 170:744.

- Miguel AI, Henriques F, Azevedo LF, Loureiro AJ, Maberley DA. Systematic review of Purtscher’s and Purtscher-like retinopathies. Eye (Lond) 2013; 27:1–13.

- Kestelyn PG, Cunningham ET Jr. HIV/AIDS and blindness. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79:208–213.

A 51-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to her primary care physician because of blurred vision, increased fatigue, palpitations, and intermittent episodes of epistaxis. Vital signs were within normal limits except for a heart rate of 110 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed pale conjunctivae and bilateral white-centered retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms

(Figures 1–4).

The results of laboratory studies:

- Hemoglobin 2.4 g/dL (reference range 12–16)

- Platelet count 78 × 109/L (150–400)

- White blood cell count 4.0 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Atypical lymphocytes 18% (0.0–3.0%)

- Reticulocyte index 0.3 (0.5–2.5%)

- Gamma gap 7.0 g/dL (< 4)

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) 5,560 mg/dL (61–356).

Bone marrow biopsy study showed complete effacement of the hematopoietic elements of normal marrow, and the diagnosis of B cell lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was made. Serum electrophoresis showed an elevated kappa-to-lambda ratio of 4.6500 (reference range 0.2600–1.6500). B cells expressed monotypic kappa surface immunoglobulin light chains CD19, CD20, and CD22. They did not express CD5. No testing was done for the MYD88 point mutation.

ROTH SPOTS

White-centered retinal hemorrhages, or Roth spots, are the result of rupture of retinal vessels with subsequent accumulation of platelets and fibrin surrounded by blood.1 Although Roth spots are mistakenly believed to be caused only by infective endocarditis, they are seen in a variety of conditions, including leukemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypoxia. Each of these conditions has a different mechanism for vessel rupture, which can include fragility of the smooth muscle vessel wall from hypoxemia and increased hydrostatic pressure in hyperviscosity syndrome.

Hypergammaglobulinemia is the most common cause of hyperviscosity syndrome and is usually associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, a type of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with the largest immunoglobulin, IgM. However, our patient presented with a variant of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with high levels of IgA, a small molecule that in high quantities can also cause hyperviscosity.

Immediate treatment is aimed at decreasing blood viscosity with plasmapheresis and controlling the underlying disease with chemotherapy.2 There have been cases of cancer-related Roth spots, in which the lesions disappeared after chemotherapy.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ROTH SPOTS

Roth spots share morphologic features with other retinal abnormalities such as “cotton wool” spots, Purtscher retinopathy, and cytomegalovirus retinitis. A thorough history and careful ophthalmologic examination can help differentiate these from Roth spots.

Cotton wool spots are a nonspecific sign of vascular insufficiency and represent an ischemic, inflammatory, or infectious condition or an embolic or neoplastic process. Most often, they represent retinopathy from poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On funduscopic examination, cotton wool spots are small, irregularly shaped, yellow-white plaques that may appear raised. They are often found over the posterior pole of the fundus. In contrast, Roth spots appear white or pale on a background of hemorrhage.

Purtscher retinopathy. Polygonal retinal whitening with sharp demarcation against the normal retina is pathognomonic of Purtscher retinopathy.4 Purtscher lesions may represent a traumatic or nontraumatic condition, including closed head injury, barotrauma, pancreatic disorder, connective tissue disease, fat embolism after long bone fracture, and even microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Patients usually describe diminished visual acuity in the context of injury or other systemic illness.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis is an important consideration in the immunocompromised patient presenting with retinal hemorrhage and is the most common cause of blindness in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).5 It is a slowly progressive disease, initially asymptomatic and involving one eye, but in some untreated patients with AIDS it may progress to the contralateral eye. When it progresses, patients usually present with floaters or vision loss. The retina can have cotton wool spots with a more diffuse pattern of hemorrhage on the periphery and white sheathing along blood vessels, eloquently described as “frosted branch angiitis.”

Our patient’s lesions appeared more punctate, in contrast to the often fulminant hemorrhagic necrosis or perivascular white lesions surrounding retinal vessels characteristic of cytomegalovirus retinitis.

THE NEED FOR ACTION

New-onset blurred vision should prompt a comprehensive history and physical examination, as it may be secondary to a life-threatening systemic disease. A thorough funduscopic examination may provide vital information and guide management and expeditious referrals for patients with time-sensitive conditions such as cancer.

Our patient decided to undergo treatment outside our hospital and so was lost to follow-up.

A 51-year-old woman with no significant medical history presented to her primary care physician because of blurred vision, increased fatigue, palpitations, and intermittent episodes of epistaxis. Vital signs were within normal limits except for a heart rate of 110 beats per minute. Physical examination revealed pale conjunctivae and bilateral white-centered retinal hemorrhages and microaneurysms

(Figures 1–4).

The results of laboratory studies:

- Hemoglobin 2.4 g/dL (reference range 12–16)

- Platelet count 78 × 109/L (150–400)

- White blood cell count 4.0 × 109/L (3.7–11.0)

- Atypical lymphocytes 18% (0.0–3.0%)

- Reticulocyte index 0.3 (0.5–2.5%)

- Gamma gap 7.0 g/dL (< 4)

- Immunoglobulin A (IgA) 5,560 mg/dL (61–356).

Bone marrow biopsy study showed complete effacement of the hematopoietic elements of normal marrow, and the diagnosis of B cell lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma was made. Serum electrophoresis showed an elevated kappa-to-lambda ratio of 4.6500 (reference range 0.2600–1.6500). B cells expressed monotypic kappa surface immunoglobulin light chains CD19, CD20, and CD22. They did not express CD5. No testing was done for the MYD88 point mutation.

ROTH SPOTS

White-centered retinal hemorrhages, or Roth spots, are the result of rupture of retinal vessels with subsequent accumulation of platelets and fibrin surrounded by blood.1 Although Roth spots are mistakenly believed to be caused only by infective endocarditis, they are seen in a variety of conditions, including leukemia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and hypoxia. Each of these conditions has a different mechanism for vessel rupture, which can include fragility of the smooth muscle vessel wall from hypoxemia and increased hydrostatic pressure in hyperviscosity syndrome.

Hypergammaglobulinemia is the most common cause of hyperviscosity syndrome and is usually associated with Waldenström macroglobulinemia, a type of lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma associated with the largest immunoglobulin, IgM. However, our patient presented with a variant of Waldenström macroglobulinemia with high levels of IgA, a small molecule that in high quantities can also cause hyperviscosity.

Immediate treatment is aimed at decreasing blood viscosity with plasmapheresis and controlling the underlying disease with chemotherapy.2 There have been cases of cancer-related Roth spots, in which the lesions disappeared after chemotherapy.3

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF ROTH SPOTS

Roth spots share morphologic features with other retinal abnormalities such as “cotton wool” spots, Purtscher retinopathy, and cytomegalovirus retinitis. A thorough history and careful ophthalmologic examination can help differentiate these from Roth spots.

Cotton wool spots are a nonspecific sign of vascular insufficiency and represent an ischemic, inflammatory, or infectious condition or an embolic or neoplastic process. Most often, they represent retinopathy from poorly controlled diabetes mellitus or hypertension. On funduscopic examination, cotton wool spots are small, irregularly shaped, yellow-white plaques that may appear raised. They are often found over the posterior pole of the fundus. In contrast, Roth spots appear white or pale on a background of hemorrhage.

Purtscher retinopathy. Polygonal retinal whitening with sharp demarcation against the normal retina is pathognomonic of Purtscher retinopathy.4 Purtscher lesions may represent a traumatic or nontraumatic condition, including closed head injury, barotrauma, pancreatic disorder, connective tissue disease, fat embolism after long bone fracture, and even microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Patients usually describe diminished visual acuity in the context of injury or other systemic illness.

Cytomegalovirus retinitis is an important consideration in the immunocompromised patient presenting with retinal hemorrhage and is the most common cause of blindness in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).5 It is a slowly progressive disease, initially asymptomatic and involving one eye, but in some untreated patients with AIDS it may progress to the contralateral eye. When it progresses, patients usually present with floaters or vision loss. The retina can have cotton wool spots with a more diffuse pattern of hemorrhage on the periphery and white sheathing along blood vessels, eloquently described as “frosted branch angiitis.”

Our patient’s lesions appeared more punctate, in contrast to the often fulminant hemorrhagic necrosis or perivascular white lesions surrounding retinal vessels characteristic of cytomegalovirus retinitis.

THE NEED FOR ACTION

New-onset blurred vision should prompt a comprehensive history and physical examination, as it may be secondary to a life-threatening systemic disease. A thorough funduscopic examination may provide vital information and guide management and expeditious referrals for patients with time-sensitive conditions such as cancer.

Our patient decided to undergo treatment outside our hospital and so was lost to follow-up.

- Ling R, James B. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (Roth spots). Postgrad Med J 1998; 74:581–582.

- Mehta J, Singhal S. Hyperviscosity syndrome in plasma cell dyscrasias. Semin Thromb Hemost 2003; 29:467–471.

- Docherty SM, Reza M, Turner G, Bowles K. Resolution of Roth spots in chronic myeloid leukaemia after treatment with imatinib. Br J Haematol 2015; 170:744.

- Miguel AI, Henriques F, Azevedo LF, Loureiro AJ, Maberley DA. Systematic review of Purtscher’s and Purtscher-like retinopathies. Eye (Lond) 2013; 27:1–13.

- Kestelyn PG, Cunningham ET Jr. HIV/AIDS and blindness. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79:208–213.

- Ling R, James B. White-centred retinal haemorrhages (Roth spots). Postgrad Med J 1998; 74:581–582.

- Mehta J, Singhal S. Hyperviscosity syndrome in plasma cell dyscrasias. Semin Thromb Hemost 2003; 29:467–471.

- Docherty SM, Reza M, Turner G, Bowles K. Resolution of Roth spots in chronic myeloid leukaemia after treatment with imatinib. Br J Haematol 2015; 170:744.

- Miguel AI, Henriques F, Azevedo LF, Loureiro AJ, Maberley DA. Systematic review of Purtscher’s and Purtscher-like retinopathies. Eye (Lond) 2013; 27:1–13.

- Kestelyn PG, Cunningham ET Jr. HIV/AIDS and blindness. Bull World Health Organ 2001; 79:208–213.

An 85-year-old with muscle pain

An 85-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease presented to our clinic with diffuse muscle pain. The pain had been present for about 3 months, but it had become noticeably worse over the past few weeks.

He was not aware of any trauma. He described the muscle pain as dull and particularly severe in his lower extremities (his thighs and calves). The pain did not limit his daily activities, nor did physical exertion or the time of day have any effect on the level of the pain.

His medications at that time included metoprolol, aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and a daily multivitamin.

He was not in acute distress. On neurologic and musculoskeletal examinations, all deep-tendon reflexes were intact, with no tenderness to palpation of the upper and lower extremities. No abnormalities were noted on the joint examination. He had full range of motion, with 5/5 muscle strength in the upper and lower extremities bilaterally and normal muscle tone. He was able to walk with ease. Results of initial laboratory testing, including creatine kinase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, were normal.

1. What should be the next best step in the evaluation of this patient’s muscle pain?

- Order tests for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody and rheumatoid factor

- Advise him to refrain from physical activity until his symptoms resolve

- Take a more detailed history, including a review of medications and supplements

- Recommend a trial of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

- Send him for radiographic imaging

Since his muscle pain has persisted for several months without improvement, a more detailed history should be taken, including a review of current medications and supplements.

Testing CCP antibody and rheumatoid factor would be useful if rheumatoid arthritis were suspected, but in the absence of demonstrable arthritis on examination, these tests would have low specificity even if the results were positive.

An NSAID may temporarily alleviate his pain, but it will not help establish a diagnosis. And in elderly patients, NSAIDs are not without complications and so should be prescribed only in appropriate situations.

Imaging would be appropriate at this point only if there was clinical suspicion of a specific disease. However, our patient has no focal deficits, and the suspicion of fracture or malignancy is low.

The medical history should include asking about current drug regimens, recent medication changes, and the use of herbal supplements, since polypharmacy is common in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

On further questioning, our patient said that his dose of simvastatin had been increased from 40 mg daily to 80 mg daily about 1 month before his symptoms appeared. He was taking a daily multivitamin but was not using herbal supplements or other over-the-counter products. He did not recall any constitutional symptoms before the onset of his current symptoms, and he had never had similar muscle pain in the past.

2. Based on the additional information from the history, what is the most likely cause of his muscle pain?

- Limited myositis secondary to recent viral infection

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Hypothyroidism

- Drug-drug interaction

- Statin-induced myalgia

Our patient’s history provided nothing to suggest viral myositis. Hypothyroidism should always be considered in patients with myalgia, but this is not likely in our patient, as he does not display other characteristics, such as diminished reflexes, hypotonia, cold intolerance, and mood instability. Even though calcium channel blockers have been known to cause myalgia in patients on statins, a drug-drug reaction is not likely, as he had not started taking a calcium channel blocker before his symptoms began. This patient did not show signs or symptoms of rhabdomyolysis, a type of myopathy in which necrosis of the muscle tissue occurs, generally causing profound weakness and pain.1

Therefore, statin-induced myopathy is the most likely cause of his diffuse muscle pain, particularly since his simvastatin had been increased 1 month before the onset of symptoms.

3. What should be the next step in his management?

- Decrease the dose of simvastatin to the last known dose he was able to tolerate

- Continue simvastatin at the same dose and then monitor

- Switch to another statin

- Add coenzyme Q10

- Stop simvastatin

Decreasing the statin dosage to the last well-tolerated dose would not be appropriate in a patient with myopathy, as the symptoms would probably not improve.2–4 Also, one should not switch to a different statin while a patient is experiencing symptoms. Rather, the statin should be stopped for at least 6 weeks or until the symptoms have fully resolved.1

Adding coenzyme Q10 is another option, especially in a patient with previously diagnosed coronary artery disease,5 when continued statin therapy is thought necessary to reduce the likelihood of repeat coronary events.

We discontinued his simvastatin. Followup 3 weeks later in the outpatient clinic showed that his symptoms were slowly improving. The symptoms had resolved completely 4 months later.

4. How should we manage our patient’s hyperlipidemia once his symptoms have resolved?

- Restart simvastatin at the 80-mg dose

- Restart simvastatin at the 40-mg dose

- Start a hydrophilic statin at full dose

- Use a drug from another class of lipid-lowering drugs

- Wait another 3 months before prescribing any lipid-lowering drug

His treatment for hyperlipidemia should be continued, considering his comorbidities. However, restarting the same statin, even at a lower dose, will likely cause his symptoms to recur. Thus, a different statin should be tried once his muscle pain has resolved.

Other classes of lipid-lowering drugs are usually less efficacious than statins, particularly when trying to control low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, so a drug from another class should not be used until other statin options have been attempted.2,6,7

Simvastatin is lipophilic. Trying a statin with hydrophilic properties (eg, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin) has been shown to convey similar cardioprotective effects with a lower propensity for myalgia, as lipophilic statins have a higher propensity to penetrate muscle tissue than do hydrophilic statins.3,4,8

Once his symptoms resolved, our patient was started on a hydrophilic statin, fluvastatin 20 mg daily. Unfortunately, his pain recurred 3 weeks later. The statin was stopped, and his symptoms again resolved.

5. Since our patient was unable to tolerate a second statin, what should be the next step in his management?

- Restart simvastatin

- Use a drug from another class to control the hyperlipidemia

- Wait at least 6 months after symptoms resolve before trying any lipid-lowering drug

- Initiate therapy with coenzyme Q10 and fish oil

- Wait for symptoms to resolve, then restart a hydrophilic statin at a lower dose and lower frequency

Restarting simvastatin will likely cause a recurrence of the myalgia. Other lipid-lowering drugs such as nicotinic acid, bile acid resins, and fibrates are not as efficacious as statins. Coenzyme Q10 and fish oil can reduce lipid levels, but they are not as efficacious as statins.

In view of our patient’s lipid profile—LDL cholesterol elevated at 167 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 31 mg/dL, triglycerides 47 mg/dL—it is important to treat his hyperlipidemia. Therefore, another attempt at statin therapy should be made once his symptoms have resolved.

Studies have shown that restarting a statin at a low dose and low frequency is effective in patients who have experienced intolerance to a statin.3,4 Our patient was treated with low-dose pravastatin (20 mg), resulting in a moderate improvement in his LDL cholesterol to 123 mg/dL.

STATIN-INDUCED MYOPATHY: ADDRESSING THE DILEMMA

Treating hyperlipidemia is important to prevent vascular events in patients with or without coronary artery disease. Statins are the most effective agents available for controlling hypercholesterolemia, specifically LDL levels, as well as for preventing myocardial infarction.

Unfortunately, significant side effects have been reported, and myopathy is the most prevalent. Statin-induced myopathy includes a combination of muscle tenderness, myalgia, and weakness.2–11 In randomized controlled trials, the risk of myopathy was estimated to be between 1.5% and 5%.6 In unselected clinic patients on high-dose statins, the rate of muscle complaints may be as high as 20%.12

The cause of statin-induced myopathy is not known, although studies have linked it to genetic defects.7 Risk factors have been identified and include personal and family history of myalgia, Asian ethnicity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes. The incidence of statin-induced myalgia is two to three times higher in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Other risk factors include female sex, liver disease, and renal dysfunction.7,8

A less common etiology is anti-HMG coenzyme A reductase antibodies. Studies have shown that these antibody levels correlate well with the amount of myositis as measured by creatine kinase levels. However, there is no consensus yet on screening for these antibodies.13

Statin therapy poses a dilemma, as there is a thin line between the benefits and the risks of side effects, especially statin-induced myopathy.3,4 Current recommendations include discontinuing the statin until symptoms fully resolve. Creatine kinase levels may be useful in assessing for potential muscle breakdown, especially in patients with reduced renal function, as this predisposes them to statin-induced myopathy, yet normal values do not preclude the diagnosis of statin-induced myopathy.3,4,7,8

Once symptoms resolve and laboratory test results normalize, a trial of a different statin is recommended. If patients become symptomatic, a trial of a low-dose hydrophilic statin at a once- or twice-weekly interval has been recommended. Several studies have assessed the efficacy of a low-dose statin with decreased frequency of administration and have consistently shown significant improvement in lipid levels.3,4 For instance, once-weekly rosuvastatin at a dose between 5 mg and 20 mg resulted in a 29% reduction in LDL cholesterol levels, and 80% of patients did not experience a recurrence of myalgia.3 Furthermore, a study of patients treated with 5 mg to 10 mg of rosuvastatin twice a week resulted in a 26% decrease in LDL cholesterol levels.4 This study also showed that when an additional non-statin lipid-lowering drug was prescribed (eg, ezetimibe, bile acid resin, nicotinic acid), more than half of the patients reached their goal lipid level.4

The addition of coenzyme Q10 and fish oil has also been suggested. Although, the evidence to support this is inconclusive, the potential benefit outweighs the risk, since the side effects are minimal.1 However, no study yet has evaluated the risks vs the benefits in patients with elevated creatine kinase.

Statin-induced myopathy is a commonly encountered adverse effect. Currently, there are no guidelines on restarting statin therapy after statin-induced myopathy; however, data suggest that statin therapy should be restarted once symptoms resolve, and that variations in dose and frequency may be necessary.1–8,14

- Fernandez G, Spatz ES, Jablecki C, Phillips PS. Statin myopathy: a common dilemma not reflected in clinical trials. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:393–403.

- Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Crouse JR, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92:79–81.

- Backes JM, Moriarty PM, Ruisinger JF, Gibson CA. Effects of once weekly rosuvastatin among patients with a prior statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100:554–555.

- Gadarla M, Kearns AK, Thompson PD. Efficacy of rosuvastatin (5 mg and 10 mg) twice a week in patients intolerant to daily statins. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1747–1748.

- Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99:1409–1412.

- Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366:1267–1278.

- Tomaszewski M, Stepien KM, Tomaszewska J, Czuczwar SJ. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep 2011; 63:859–866.

- SEARCH Collaborative Group; Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, et al. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:789–799.

- Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003; 289:1681–1690.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF heart protection study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360:7–22.

- Guyton JR. Benefit versus risk in statin treatment. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:95C–97C.

- Buettner C, Davis RB, Leveille SG, Mittleman MA, Mukamal KJ. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and statin use. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23:1182–1186.

- Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:4087–4093.

- The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:1349–1357.

An 85-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease presented to our clinic with diffuse muscle pain. The pain had been present for about 3 months, but it had become noticeably worse over the past few weeks.

He was not aware of any trauma. He described the muscle pain as dull and particularly severe in his lower extremities (his thighs and calves). The pain did not limit his daily activities, nor did physical exertion or the time of day have any effect on the level of the pain.

His medications at that time included metoprolol, aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and a daily multivitamin.

He was not in acute distress. On neurologic and musculoskeletal examinations, all deep-tendon reflexes were intact, with no tenderness to palpation of the upper and lower extremities. No abnormalities were noted on the joint examination. He had full range of motion, with 5/5 muscle strength in the upper and lower extremities bilaterally and normal muscle tone. He was able to walk with ease. Results of initial laboratory testing, including creatine kinase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, were normal.

1. What should be the next best step in the evaluation of this patient’s muscle pain?

- Order tests for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody and rheumatoid factor

- Advise him to refrain from physical activity until his symptoms resolve

- Take a more detailed history, including a review of medications and supplements

- Recommend a trial of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

- Send him for radiographic imaging

Since his muscle pain has persisted for several months without improvement, a more detailed history should be taken, including a review of current medications and supplements.

Testing CCP antibody and rheumatoid factor would be useful if rheumatoid arthritis were suspected, but in the absence of demonstrable arthritis on examination, these tests would have low specificity even if the results were positive.

An NSAID may temporarily alleviate his pain, but it will not help establish a diagnosis. And in elderly patients, NSAIDs are not without complications and so should be prescribed only in appropriate situations.

Imaging would be appropriate at this point only if there was clinical suspicion of a specific disease. However, our patient has no focal deficits, and the suspicion of fracture or malignancy is low.

The medical history should include asking about current drug regimens, recent medication changes, and the use of herbal supplements, since polypharmacy is common in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

On further questioning, our patient said that his dose of simvastatin had been increased from 40 mg daily to 80 mg daily about 1 month before his symptoms appeared. He was taking a daily multivitamin but was not using herbal supplements or other over-the-counter products. He did not recall any constitutional symptoms before the onset of his current symptoms, and he had never had similar muscle pain in the past.

2. Based on the additional information from the history, what is the most likely cause of his muscle pain?

- Limited myositis secondary to recent viral infection

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Hypothyroidism

- Drug-drug interaction

- Statin-induced myalgia

Our patient’s history provided nothing to suggest viral myositis. Hypothyroidism should always be considered in patients with myalgia, but this is not likely in our patient, as he does not display other characteristics, such as diminished reflexes, hypotonia, cold intolerance, and mood instability. Even though calcium channel blockers have been known to cause myalgia in patients on statins, a drug-drug reaction is not likely, as he had not started taking a calcium channel blocker before his symptoms began. This patient did not show signs or symptoms of rhabdomyolysis, a type of myopathy in which necrosis of the muscle tissue occurs, generally causing profound weakness and pain.1

Therefore, statin-induced myopathy is the most likely cause of his diffuse muscle pain, particularly since his simvastatin had been increased 1 month before the onset of symptoms.

3. What should be the next step in his management?

- Decrease the dose of simvastatin to the last known dose he was able to tolerate

- Continue simvastatin at the same dose and then monitor

- Switch to another statin

- Add coenzyme Q10

- Stop simvastatin

Decreasing the statin dosage to the last well-tolerated dose would not be appropriate in a patient with myopathy, as the symptoms would probably not improve.2–4 Also, one should not switch to a different statin while a patient is experiencing symptoms. Rather, the statin should be stopped for at least 6 weeks or until the symptoms have fully resolved.1

Adding coenzyme Q10 is another option, especially in a patient with previously diagnosed coronary artery disease,5 when continued statin therapy is thought necessary to reduce the likelihood of repeat coronary events.

We discontinued his simvastatin. Followup 3 weeks later in the outpatient clinic showed that his symptoms were slowly improving. The symptoms had resolved completely 4 months later.

4. How should we manage our patient’s hyperlipidemia once his symptoms have resolved?

- Restart simvastatin at the 80-mg dose

- Restart simvastatin at the 40-mg dose

- Start a hydrophilic statin at full dose

- Use a drug from another class of lipid-lowering drugs

- Wait another 3 months before prescribing any lipid-lowering drug

His treatment for hyperlipidemia should be continued, considering his comorbidities. However, restarting the same statin, even at a lower dose, will likely cause his symptoms to recur. Thus, a different statin should be tried once his muscle pain has resolved.

Other classes of lipid-lowering drugs are usually less efficacious than statins, particularly when trying to control low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, so a drug from another class should not be used until other statin options have been attempted.2,6,7

Simvastatin is lipophilic. Trying a statin with hydrophilic properties (eg, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin) has been shown to convey similar cardioprotective effects with a lower propensity for myalgia, as lipophilic statins have a higher propensity to penetrate muscle tissue than do hydrophilic statins.3,4,8

Once his symptoms resolved, our patient was started on a hydrophilic statin, fluvastatin 20 mg daily. Unfortunately, his pain recurred 3 weeks later. The statin was stopped, and his symptoms again resolved.

5. Since our patient was unable to tolerate a second statin, what should be the next step in his management?

- Restart simvastatin

- Use a drug from another class to control the hyperlipidemia

- Wait at least 6 months after symptoms resolve before trying any lipid-lowering drug

- Initiate therapy with coenzyme Q10 and fish oil

- Wait for symptoms to resolve, then restart a hydrophilic statin at a lower dose and lower frequency

Restarting simvastatin will likely cause a recurrence of the myalgia. Other lipid-lowering drugs such as nicotinic acid, bile acid resins, and fibrates are not as efficacious as statins. Coenzyme Q10 and fish oil can reduce lipid levels, but they are not as efficacious as statins.

In view of our patient’s lipid profile—LDL cholesterol elevated at 167 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 31 mg/dL, triglycerides 47 mg/dL—it is important to treat his hyperlipidemia. Therefore, another attempt at statin therapy should be made once his symptoms have resolved.

Studies have shown that restarting a statin at a low dose and low frequency is effective in patients who have experienced intolerance to a statin.3,4 Our patient was treated with low-dose pravastatin (20 mg), resulting in a moderate improvement in his LDL cholesterol to 123 mg/dL.

STATIN-INDUCED MYOPATHY: ADDRESSING THE DILEMMA

Treating hyperlipidemia is important to prevent vascular events in patients with or without coronary artery disease. Statins are the most effective agents available for controlling hypercholesterolemia, specifically LDL levels, as well as for preventing myocardial infarction.

Unfortunately, significant side effects have been reported, and myopathy is the most prevalent. Statin-induced myopathy includes a combination of muscle tenderness, myalgia, and weakness.2–11 In randomized controlled trials, the risk of myopathy was estimated to be between 1.5% and 5%.6 In unselected clinic patients on high-dose statins, the rate of muscle complaints may be as high as 20%.12

The cause of statin-induced myopathy is not known, although studies have linked it to genetic defects.7 Risk factors have been identified and include personal and family history of myalgia, Asian ethnicity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes. The incidence of statin-induced myalgia is two to three times higher in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Other risk factors include female sex, liver disease, and renal dysfunction.7,8

A less common etiology is anti-HMG coenzyme A reductase antibodies. Studies have shown that these antibody levels correlate well with the amount of myositis as measured by creatine kinase levels. However, there is no consensus yet on screening for these antibodies.13

Statin therapy poses a dilemma, as there is a thin line between the benefits and the risks of side effects, especially statin-induced myopathy.3,4 Current recommendations include discontinuing the statin until symptoms fully resolve. Creatine kinase levels may be useful in assessing for potential muscle breakdown, especially in patients with reduced renal function, as this predisposes them to statin-induced myopathy, yet normal values do not preclude the diagnosis of statin-induced myopathy.3,4,7,8

Once symptoms resolve and laboratory test results normalize, a trial of a different statin is recommended. If patients become symptomatic, a trial of a low-dose hydrophilic statin at a once- or twice-weekly interval has been recommended. Several studies have assessed the efficacy of a low-dose statin with decreased frequency of administration and have consistently shown significant improvement in lipid levels.3,4 For instance, once-weekly rosuvastatin at a dose between 5 mg and 20 mg resulted in a 29% reduction in LDL cholesterol levels, and 80% of patients did not experience a recurrence of myalgia.3 Furthermore, a study of patients treated with 5 mg to 10 mg of rosuvastatin twice a week resulted in a 26% decrease in LDL cholesterol levels.4 This study also showed that when an additional non-statin lipid-lowering drug was prescribed (eg, ezetimibe, bile acid resin, nicotinic acid), more than half of the patients reached their goal lipid level.4

The addition of coenzyme Q10 and fish oil has also been suggested. Although, the evidence to support this is inconclusive, the potential benefit outweighs the risk, since the side effects are minimal.1 However, no study yet has evaluated the risks vs the benefits in patients with elevated creatine kinase.

Statin-induced myopathy is a commonly encountered adverse effect. Currently, there are no guidelines on restarting statin therapy after statin-induced myopathy; however, data suggest that statin therapy should be restarted once symptoms resolve, and that variations in dose and frequency may be necessary.1–8,14

An 85-year-old man with hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and coronary artery disease presented to our clinic with diffuse muscle pain. The pain had been present for about 3 months, but it had become noticeably worse over the past few weeks.

He was not aware of any trauma. He described the muscle pain as dull and particularly severe in his lower extremities (his thighs and calves). The pain did not limit his daily activities, nor did physical exertion or the time of day have any effect on the level of the pain.

His medications at that time included metoprolol, aspirin, hydrochlorothiazide, simvastatin, and a daily multivitamin.

He was not in acute distress. On neurologic and musculoskeletal examinations, all deep-tendon reflexes were intact, with no tenderness to palpation of the upper and lower extremities. No abnormalities were noted on the joint examination. He had full range of motion, with 5/5 muscle strength in the upper and lower extremities bilaterally and normal muscle tone. He was able to walk with ease. Results of initial laboratory testing, including creatine kinase and erythrocyte sedimentation rate, were normal.

1. What should be the next best step in the evaluation of this patient’s muscle pain?

- Order tests for cyclic citrullinated peptide (CCP) antibody and rheumatoid factor

- Advise him to refrain from physical activity until his symptoms resolve

- Take a more detailed history, including a review of medications and supplements

- Recommend a trial of a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

- Send him for radiographic imaging

Since his muscle pain has persisted for several months without improvement, a more detailed history should be taken, including a review of current medications and supplements.

Testing CCP antibody and rheumatoid factor would be useful if rheumatoid arthritis were suspected, but in the absence of demonstrable arthritis on examination, these tests would have low specificity even if the results were positive.

An NSAID may temporarily alleviate his pain, but it will not help establish a diagnosis. And in elderly patients, NSAIDs are not without complications and so should be prescribed only in appropriate situations.

Imaging would be appropriate at this point only if there was clinical suspicion of a specific disease. However, our patient has no focal deficits, and the suspicion of fracture or malignancy is low.

The medical history should include asking about current drug regimens, recent medication changes, and the use of herbal supplements, since polypharmacy is common in elderly patients with multiple comorbidities.

On further questioning, our patient said that his dose of simvastatin had been increased from 40 mg daily to 80 mg daily about 1 month before his symptoms appeared. He was taking a daily multivitamin but was not using herbal supplements or other over-the-counter products. He did not recall any constitutional symptoms before the onset of his current symptoms, and he had never had similar muscle pain in the past.

2. Based on the additional information from the history, what is the most likely cause of his muscle pain?

- Limited myositis secondary to recent viral infection

- Rhabdomyolysis

- Hypothyroidism

- Drug-drug interaction

- Statin-induced myalgia

Our patient’s history provided nothing to suggest viral myositis. Hypothyroidism should always be considered in patients with myalgia, but this is not likely in our patient, as he does not display other characteristics, such as diminished reflexes, hypotonia, cold intolerance, and mood instability. Even though calcium channel blockers have been known to cause myalgia in patients on statins, a drug-drug reaction is not likely, as he had not started taking a calcium channel blocker before his symptoms began. This patient did not show signs or symptoms of rhabdomyolysis, a type of myopathy in which necrosis of the muscle tissue occurs, generally causing profound weakness and pain.1

Therefore, statin-induced myopathy is the most likely cause of his diffuse muscle pain, particularly since his simvastatin had been increased 1 month before the onset of symptoms.

3. What should be the next step in his management?

- Decrease the dose of simvastatin to the last known dose he was able to tolerate

- Continue simvastatin at the same dose and then monitor

- Switch to another statin

- Add coenzyme Q10

- Stop simvastatin

Decreasing the statin dosage to the last well-tolerated dose would not be appropriate in a patient with myopathy, as the symptoms would probably not improve.2–4 Also, one should not switch to a different statin while a patient is experiencing symptoms. Rather, the statin should be stopped for at least 6 weeks or until the symptoms have fully resolved.1

Adding coenzyme Q10 is another option, especially in a patient with previously diagnosed coronary artery disease,5 when continued statin therapy is thought necessary to reduce the likelihood of repeat coronary events.

We discontinued his simvastatin. Followup 3 weeks later in the outpatient clinic showed that his symptoms were slowly improving. The symptoms had resolved completely 4 months later.

4. How should we manage our patient’s hyperlipidemia once his symptoms have resolved?

- Restart simvastatin at the 80-mg dose

- Restart simvastatin at the 40-mg dose

- Start a hydrophilic statin at full dose

- Use a drug from another class of lipid-lowering drugs

- Wait another 3 months before prescribing any lipid-lowering drug

His treatment for hyperlipidemia should be continued, considering his comorbidities. However, restarting the same statin, even at a lower dose, will likely cause his symptoms to recur. Thus, a different statin should be tried once his muscle pain has resolved.

Other classes of lipid-lowering drugs are usually less efficacious than statins, particularly when trying to control low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, so a drug from another class should not be used until other statin options have been attempted.2,6,7

Simvastatin is lipophilic. Trying a statin with hydrophilic properties (eg, pravastatin, rosuvastatin, fluvastatin) has been shown to convey similar cardioprotective effects with a lower propensity for myalgia, as lipophilic statins have a higher propensity to penetrate muscle tissue than do hydrophilic statins.3,4,8

Once his symptoms resolved, our patient was started on a hydrophilic statin, fluvastatin 20 mg daily. Unfortunately, his pain recurred 3 weeks later. The statin was stopped, and his symptoms again resolved.

5. Since our patient was unable to tolerate a second statin, what should be the next step in his management?

- Restart simvastatin

- Use a drug from another class to control the hyperlipidemia

- Wait at least 6 months after symptoms resolve before trying any lipid-lowering drug

- Initiate therapy with coenzyme Q10 and fish oil

- Wait for symptoms to resolve, then restart a hydrophilic statin at a lower dose and lower frequency

Restarting simvastatin will likely cause a recurrence of the myalgia. Other lipid-lowering drugs such as nicotinic acid, bile acid resins, and fibrates are not as efficacious as statins. Coenzyme Q10 and fish oil can reduce lipid levels, but they are not as efficacious as statins.

In view of our patient’s lipid profile—LDL cholesterol elevated at 167 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol 31 mg/dL, triglycerides 47 mg/dL—it is important to treat his hyperlipidemia. Therefore, another attempt at statin therapy should be made once his symptoms have resolved.

Studies have shown that restarting a statin at a low dose and low frequency is effective in patients who have experienced intolerance to a statin.3,4 Our patient was treated with low-dose pravastatin (20 mg), resulting in a moderate improvement in his LDL cholesterol to 123 mg/dL.

STATIN-INDUCED MYOPATHY: ADDRESSING THE DILEMMA

Treating hyperlipidemia is important to prevent vascular events in patients with or without coronary artery disease. Statins are the most effective agents available for controlling hypercholesterolemia, specifically LDL levels, as well as for preventing myocardial infarction.

Unfortunately, significant side effects have been reported, and myopathy is the most prevalent. Statin-induced myopathy includes a combination of muscle tenderness, myalgia, and weakness.2–11 In randomized controlled trials, the risk of myopathy was estimated to be between 1.5% and 5%.6 In unselected clinic patients on high-dose statins, the rate of muscle complaints may be as high as 20%.12

The cause of statin-induced myopathy is not known, although studies have linked it to genetic defects.7 Risk factors have been identified and include personal and family history of myalgia, Asian ethnicity, hypothyroidism, and type 1 diabetes. The incidence of statin-induced myalgia is two to three times higher in patients on corticosteroid therapy. Other risk factors include female sex, liver disease, and renal dysfunction.7,8

A less common etiology is anti-HMG coenzyme A reductase antibodies. Studies have shown that these antibody levels correlate well with the amount of myositis as measured by creatine kinase levels. However, there is no consensus yet on screening for these antibodies.13

Statin therapy poses a dilemma, as there is a thin line between the benefits and the risks of side effects, especially statin-induced myopathy.3,4 Current recommendations include discontinuing the statin until symptoms fully resolve. Creatine kinase levels may be useful in assessing for potential muscle breakdown, especially in patients with reduced renal function, as this predisposes them to statin-induced myopathy, yet normal values do not preclude the diagnosis of statin-induced myopathy.3,4,7,8

Once symptoms resolve and laboratory test results normalize, a trial of a different statin is recommended. If patients become symptomatic, a trial of a low-dose hydrophilic statin at a once- or twice-weekly interval has been recommended. Several studies have assessed the efficacy of a low-dose statin with decreased frequency of administration and have consistently shown significant improvement in lipid levels.3,4 For instance, once-weekly rosuvastatin at a dose between 5 mg and 20 mg resulted in a 29% reduction in LDL cholesterol levels, and 80% of patients did not experience a recurrence of myalgia.3 Furthermore, a study of patients treated with 5 mg to 10 mg of rosuvastatin twice a week resulted in a 26% decrease in LDL cholesterol levels.4 This study also showed that when an additional non-statin lipid-lowering drug was prescribed (eg, ezetimibe, bile acid resin, nicotinic acid), more than half of the patients reached their goal lipid level.4

The addition of coenzyme Q10 and fish oil has also been suggested. Although, the evidence to support this is inconclusive, the potential benefit outweighs the risk, since the side effects are minimal.1 However, no study yet has evaluated the risks vs the benefits in patients with elevated creatine kinase.

Statin-induced myopathy is a commonly encountered adverse effect. Currently, there are no guidelines on restarting statin therapy after statin-induced myopathy; however, data suggest that statin therapy should be restarted once symptoms resolve, and that variations in dose and frequency may be necessary.1–8,14

- Fernandez G, Spatz ES, Jablecki C, Phillips PS. Statin myopathy: a common dilemma not reflected in clinical trials. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:393–403.

- Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Crouse JR, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92:79–81.

- Backes JM, Moriarty PM, Ruisinger JF, Gibson CA. Effects of once weekly rosuvastatin among patients with a prior statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100:554–555.

- Gadarla M, Kearns AK, Thompson PD. Efficacy of rosuvastatin (5 mg and 10 mg) twice a week in patients intolerant to daily statins. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1747–1748.

- Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99:1409–1412.

- Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366:1267–1278.

- Tomaszewski M, Stepien KM, Tomaszewska J, Czuczwar SJ. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep 2011; 63:859–866.

- SEARCH Collaborative Group; Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, et al. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:789–799.

- Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003; 289:1681–1690.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF heart protection study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360:7–22.

- Guyton JR. Benefit versus risk in statin treatment. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:95C–97C.

- Buettner C, Davis RB, Leveille SG, Mittleman MA, Mukamal KJ. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and statin use. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23:1182–1186.

- Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:4087–4093.

- The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:1349–1357.

- Fernandez G, Spatz ES, Jablecki C, Phillips PS. Statin myopathy: a common dilemma not reflected in clinical trials. Cleve Clin J Med 2011; 78:393–403.

- Foley KA, Simpson RJ, Crouse JR, Weiss TW, Markson LE, Alexander CM. Effectiveness of statin titration on low-density lipoprotein cholesterol goal attainment in patients at high risk of atherogenic events. Am J Cardiol 2003; 92:79–81.

- Backes JM, Moriarty PM, Ruisinger JF, Gibson CA. Effects of once weekly rosuvastatin among patients with a prior statin intolerance. Am J Cardiol 2007; 100:554–555.

- Gadarla M, Kearns AK, Thompson PD. Efficacy of rosuvastatin (5 mg and 10 mg) twice a week in patients intolerant to daily statins. Am J Cardiol 2008; 101:1747–1748.

- Caso G, Kelly P, McNurlan MA, Lawson WE. Effect of coenzyme q10 on myopathic symptoms in patients treated with statins. Am J Cardiol 2007; 99:1409–1412.

- Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet 2005; 366:1267–1278.

- Tomaszewski M, Stepien KM, Tomaszewska J, Czuczwar SJ. Statin-induced myopathies. Pharmacol Rep 2011; 63:859–866.

- SEARCH Collaborative Group; Link E, Parish S, Armitage J, et al. SLCO1B1 variants and statin-induced myopathy—a genomewide study. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:789–799.

- Thompson PD, Clarkson P, Karas RH. Statin-associated myopathy. JAMA 2003; 289:1681–1690.

- Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF heart protection study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360:7–22.

- Guyton JR. Benefit versus risk in statin treatment. Am J Cardiol 2006; 97:95C–97C.

- Buettner C, Davis RB, Leveille SG, Mittleman MA, Mukamal KJ. Prevalence of musculoskeletal pain and statin use. J Gen Intern Med 2008; 23:1182–1186.

- Werner JL, Christopher-Stine L, Ghazarian SR, et al. Antibody levels correlate with creatine kinase levels and strength in anti-3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase-associated autoimmune myopathy. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64:4087–4093.

- The Long-Term Intervention with Pravastatin in Ischaemic Disease (LIPID) Study Group. Prevention of cardiovascular events and death with pravastatin in patients with coronary heart disease and a broad range of initial cholesterol levels. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:1349–1357.