User login

Are anti-TNF drugs safe for pregnant women with inflammatory bowel disease?

Yes, anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can be continued during pregnancy.

IBD is often diagnosed and treated in women during their reproductive years. Consequently, these patients face important decisions about the management of their disease and the safety of their baby. Clinicians should be prepared to offer guidance by discussing the risks and benefits of anti-TNF agents with their pregnant patients who have IBD, as well as with those considering pregnancy.

STUDIES OF THE POTENTIAL RISKS

Anti-TNF agents are monoclonal antibodies. Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are actively transported into the fetal circulation via the placenta, mainly during the second and third trimesters. Certolizumab crosses the placenta only by passive means, because it lacks the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region required for placental transfer.1

Effects on pregnancy outcomes

In a 2016 meta-analysis,2 of 1,242 pregnancies in women with IBD, 482 were in women on anti-TNF therapy. It found no statistically significant difference in rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes including congenital abnormality, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

A meta-analysis of 1,216 pregnant women with IBD found no statistically significant differences in rates of spontaneous or elective abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or congenital malformation in those on anti-TNF therapy vs controls.3

A systematic review of 58 studies including more than 1,500 pregnant women with IBD who were exposed to anti-TNF agents concluded that there was no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, stillbirth, low birth weight, congenital malformation, or infection.4

A retrospective cohort study of 66 pregnant patients with IBD from several centers in Spain found that anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy during pregnancy did not increase the risk of pregnancy complications or neonatal complications.5

Effects on newborns

Cord blood studies have shown that maternal use of infliximab and adalimumab results in a detectable serum level in newborns, while cord blood levels of certolizumab are much lower.1,6 In some studies, anti-TNF drugs were detectable in infants for up to 6 months after birth, whereas other studies found that detectable serum levels dropped soon after birth.1,7

Addressing concern about an increased risk of infection or dysfunctional immune development in newborns exposed to anti-TNF drugs in utero, a systematic review found no increased risk.4 A retrospective multicenter cohort study of 841 children also reported no association between in utero exposure to anti-TNF agents and risk of severe infection in the short term or long term (mean of 4 years).8 Additional studies are under way to determine long-term risk to the newborn.7

THE TORONTO CONSENSUS GUIDELINES

The Toronto consensus guidelines strongly recommend continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in women with IBD who began maintenance therapy before conception.6

If a patient strongly prefers to stop therapy during pregnancy to limit fetal exposure, the Toronto consensus recommends giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation. However, this should only be considered in patients whose IBD is in remission and at low risk of relapse.6,9

Although anti-TNF drugs may differ in terms of placental transfer, agents should not be switched in stable patients, as switching increases the risk of relapse.10

BENEFITS OF CONTINUING THERAPY

Active IBD poses a significantly greater risk to the mother and the baby than continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy.1,7 The primary benefit of continuing therapy is to maintain disease remission.

Among women with active IBD at the time of conception, one-third will have improvement in disease activity during the course of their pregnancy, one-third will have no change, and one-third will have worsening of disease activity. But if IBD is in remission at the time of conception, it will remain in remission in nearly 80% of women during pregnancy.1

Women with active IBD are at increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction.1,2,5 Also, women with IBD have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, particularly if they have active disease during pregnancy.1 Therefore, achieving and maintaining remission are vital in the management of the pregnant patient with IBD.

CONSIDERATIONS AFTER BIRTH: BREAST-FEEDING AND VACCINATION

Breast-feeding is considered safe. Minuscule amounts of infliximab or adalimumab are transferred in breast milk but are unlikely to result in systemic immune suppression in the infant.7

Live-attenuated vaccines should be avoided for the first 6 months in infants exposed to anti-TNF agents in utero.1,7,11 All other vaccines, including hepatitis B virus vaccine, should be given according to standard schedules.6

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

The goal of managing IBD in women of reproductive age is to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes for both mother and baby. We recommend a team approach, working closely with a gastroenterologist and a high-risk-pregnancy obstetrician, if available.

Patients should continue anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy because evidence supports its safety. If a woman wants to stop therapy and is at low risk of relapse, we recommend giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, then promptly resuming therapy postpartum.

Live-attenuated vaccines (eg, influenza, rotavirus) should be avoided for the first 6 months in babies born to mothers on anti-TNF therapy.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Clinician’s Guide. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2017. doi:10.1002/9781119077633

- Shihab Z, Yeomans ND, De Cruz P. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapies and inflammatory bowel disease pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10(8):979–988. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv234

- Narula N, Al-Dabbagh, Dhillon A, Sands BE, Marshall JK. Anti-TNF alpha therapies are safe during pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20(10):1862–1869. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000092

- Nielsen OH, Loftus EV Jr, Jess T. Safety of TNF-alpha inhibitors during IBD pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Med 2013; 11:174. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-174

- Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Domenech E, et al. Safety of thiopurines and anti-TNF-alpha drugs during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):433–440. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.430

- Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al; IBD in Pregnancy Consensus Group; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. The Toronto consensus statements for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(3):734–757.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.003

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro, M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1426–1438. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.171

- Chaparro M, Verreth A, Lobaton T, et al. Long-term safety of in utero exposure to anti-TNF alpha drugs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from the multicenter European TEDDY Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(3):396–403. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.501

- de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, van der Ent C, Steegers EA, van der Woude CJ. Tailored anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in patients with IBD: maternal and fetal safety. Gut 2016; 65(8):1261–1268. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309321

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ballet V, et al. Switch to adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease controlled by maintenance infliximab: prospective randomised SWITCH trial. Gut 2012; 61(2):229–234. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300755

- Saha S. Medication management in the pregnant IBD patient. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(5):667–669. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.22

Yes, anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can be continued during pregnancy.

IBD is often diagnosed and treated in women during their reproductive years. Consequently, these patients face important decisions about the management of their disease and the safety of their baby. Clinicians should be prepared to offer guidance by discussing the risks and benefits of anti-TNF agents with their pregnant patients who have IBD, as well as with those considering pregnancy.

STUDIES OF THE POTENTIAL RISKS

Anti-TNF agents are monoclonal antibodies. Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are actively transported into the fetal circulation via the placenta, mainly during the second and third trimesters. Certolizumab crosses the placenta only by passive means, because it lacks the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region required for placental transfer.1

Effects on pregnancy outcomes

In a 2016 meta-analysis,2 of 1,242 pregnancies in women with IBD, 482 were in women on anti-TNF therapy. It found no statistically significant difference in rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes including congenital abnormality, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

A meta-analysis of 1,216 pregnant women with IBD found no statistically significant differences in rates of spontaneous or elective abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or congenital malformation in those on anti-TNF therapy vs controls.3

A systematic review of 58 studies including more than 1,500 pregnant women with IBD who were exposed to anti-TNF agents concluded that there was no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, stillbirth, low birth weight, congenital malformation, or infection.4

A retrospective cohort study of 66 pregnant patients with IBD from several centers in Spain found that anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy during pregnancy did not increase the risk of pregnancy complications or neonatal complications.5

Effects on newborns

Cord blood studies have shown that maternal use of infliximab and adalimumab results in a detectable serum level in newborns, while cord blood levels of certolizumab are much lower.1,6 In some studies, anti-TNF drugs were detectable in infants for up to 6 months after birth, whereas other studies found that detectable serum levels dropped soon after birth.1,7

Addressing concern about an increased risk of infection or dysfunctional immune development in newborns exposed to anti-TNF drugs in utero, a systematic review found no increased risk.4 A retrospective multicenter cohort study of 841 children also reported no association between in utero exposure to anti-TNF agents and risk of severe infection in the short term or long term (mean of 4 years).8 Additional studies are under way to determine long-term risk to the newborn.7

THE TORONTO CONSENSUS GUIDELINES

The Toronto consensus guidelines strongly recommend continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in women with IBD who began maintenance therapy before conception.6

If a patient strongly prefers to stop therapy during pregnancy to limit fetal exposure, the Toronto consensus recommends giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation. However, this should only be considered in patients whose IBD is in remission and at low risk of relapse.6,9

Although anti-TNF drugs may differ in terms of placental transfer, agents should not be switched in stable patients, as switching increases the risk of relapse.10

BENEFITS OF CONTINUING THERAPY

Active IBD poses a significantly greater risk to the mother and the baby than continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy.1,7 The primary benefit of continuing therapy is to maintain disease remission.

Among women with active IBD at the time of conception, one-third will have improvement in disease activity during the course of their pregnancy, one-third will have no change, and one-third will have worsening of disease activity. But if IBD is in remission at the time of conception, it will remain in remission in nearly 80% of women during pregnancy.1

Women with active IBD are at increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction.1,2,5 Also, women with IBD have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, particularly if they have active disease during pregnancy.1 Therefore, achieving and maintaining remission are vital in the management of the pregnant patient with IBD.

CONSIDERATIONS AFTER BIRTH: BREAST-FEEDING AND VACCINATION

Breast-feeding is considered safe. Minuscule amounts of infliximab or adalimumab are transferred in breast milk but are unlikely to result in systemic immune suppression in the infant.7

Live-attenuated vaccines should be avoided for the first 6 months in infants exposed to anti-TNF agents in utero.1,7,11 All other vaccines, including hepatitis B virus vaccine, should be given according to standard schedules.6

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

The goal of managing IBD in women of reproductive age is to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes for both mother and baby. We recommend a team approach, working closely with a gastroenterologist and a high-risk-pregnancy obstetrician, if available.

Patients should continue anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy because evidence supports its safety. If a woman wants to stop therapy and is at low risk of relapse, we recommend giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, then promptly resuming therapy postpartum.

Live-attenuated vaccines (eg, influenza, rotavirus) should be avoided for the first 6 months in babies born to mothers on anti-TNF therapy.

Yes, anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) therapy for inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can be continued during pregnancy.

IBD is often diagnosed and treated in women during their reproductive years. Consequently, these patients face important decisions about the management of their disease and the safety of their baby. Clinicians should be prepared to offer guidance by discussing the risks and benefits of anti-TNF agents with their pregnant patients who have IBD, as well as with those considering pregnancy.

STUDIES OF THE POTENTIAL RISKS

Anti-TNF agents are monoclonal antibodies. Infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are actively transported into the fetal circulation via the placenta, mainly during the second and third trimesters. Certolizumab crosses the placenta only by passive means, because it lacks the fragment crystallizable (Fc) region required for placental transfer.1

Effects on pregnancy outcomes

In a 2016 meta-analysis,2 of 1,242 pregnancies in women with IBD, 482 were in women on anti-TNF therapy. It found no statistically significant difference in rates of adverse pregnancy outcomes including congenital abnormality, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

A meta-analysis of 1,216 pregnant women with IBD found no statistically significant differences in rates of spontaneous or elective abortion, preterm birth, low birth weight, or congenital malformation in those on anti-TNF therapy vs controls.3

A systematic review of 58 studies including more than 1,500 pregnant women with IBD who were exposed to anti-TNF agents concluded that there was no association with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as spontaneous abortion, preterm delivery, stillbirth, low birth weight, congenital malformation, or infection.4

A retrospective cohort study of 66 pregnant patients with IBD from several centers in Spain found that anti-TNF or thiopurine therapy during pregnancy did not increase the risk of pregnancy complications or neonatal complications.5

Effects on newborns

Cord blood studies have shown that maternal use of infliximab and adalimumab results in a detectable serum level in newborns, while cord blood levels of certolizumab are much lower.1,6 In some studies, anti-TNF drugs were detectable in infants for up to 6 months after birth, whereas other studies found that detectable serum levels dropped soon after birth.1,7

Addressing concern about an increased risk of infection or dysfunctional immune development in newborns exposed to anti-TNF drugs in utero, a systematic review found no increased risk.4 A retrospective multicenter cohort study of 841 children also reported no association between in utero exposure to anti-TNF agents and risk of severe infection in the short term or long term (mean of 4 years).8 Additional studies are under way to determine long-term risk to the newborn.7

THE TORONTO CONSENSUS GUIDELINES

The Toronto consensus guidelines strongly recommend continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in women with IBD who began maintenance therapy before conception.6

If a patient strongly prefers to stop therapy during pregnancy to limit fetal exposure, the Toronto consensus recommends giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation. However, this should only be considered in patients whose IBD is in remission and at low risk of relapse.6,9

Although anti-TNF drugs may differ in terms of placental transfer, agents should not be switched in stable patients, as switching increases the risk of relapse.10

BENEFITS OF CONTINUING THERAPY

Active IBD poses a significantly greater risk to the mother and the baby than continuing anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy.1,7 The primary benefit of continuing therapy is to maintain disease remission.

Among women with active IBD at the time of conception, one-third will have improvement in disease activity during the course of their pregnancy, one-third will have no change, and one-third will have worsening of disease activity. But if IBD is in remission at the time of conception, it will remain in remission in nearly 80% of women during pregnancy.1

Women with active IBD are at increased risk of preterm delivery, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction.1,2,5 Also, women with IBD have an increased risk of venous thromboembolism, particularly if they have active disease during pregnancy.1 Therefore, achieving and maintaining remission are vital in the management of the pregnant patient with IBD.

CONSIDERATIONS AFTER BIRTH: BREAST-FEEDING AND VACCINATION

Breast-feeding is considered safe. Minuscule amounts of infliximab or adalimumab are transferred in breast milk but are unlikely to result in systemic immune suppression in the infant.7

Live-attenuated vaccines should be avoided for the first 6 months in infants exposed to anti-TNF agents in utero.1,7,11 All other vaccines, including hepatitis B virus vaccine, should be given according to standard schedules.6

OUR RECOMMENDATIONS

The goal of managing IBD in women of reproductive age is to minimize the risk of adverse outcomes for both mother and baby. We recommend a team approach, working closely with a gastroenterologist and a high-risk-pregnancy obstetrician, if available.

Patients should continue anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy because evidence supports its safety. If a woman wants to stop therapy and is at low risk of relapse, we recommend giving the last dose at 22 to 24 weeks of gestation, then promptly resuming therapy postpartum.

Live-attenuated vaccines (eg, influenza, rotavirus) should be avoided for the first 6 months in babies born to mothers on anti-TNF therapy.

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Clinician’s Guide. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2017. doi:10.1002/9781119077633

- Shihab Z, Yeomans ND, De Cruz P. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapies and inflammatory bowel disease pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10(8):979–988. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv234

- Narula N, Al-Dabbagh, Dhillon A, Sands BE, Marshall JK. Anti-TNF alpha therapies are safe during pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20(10):1862–1869. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000092

- Nielsen OH, Loftus EV Jr, Jess T. Safety of TNF-alpha inhibitors during IBD pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Med 2013; 11:174. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-174

- Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Domenech E, et al. Safety of thiopurines and anti-TNF-alpha drugs during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):433–440. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.430

- Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al; IBD in Pregnancy Consensus Group; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. The Toronto consensus statements for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(3):734–757.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.003

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro, M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1426–1438. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.171

- Chaparro M, Verreth A, Lobaton T, et al. Long-term safety of in utero exposure to anti-TNF alpha drugs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from the multicenter European TEDDY Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(3):396–403. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.501

- de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, van der Ent C, Steegers EA, van der Woude CJ. Tailored anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in patients with IBD: maternal and fetal safety. Gut 2016; 65(8):1261–1268. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309321

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ballet V, et al. Switch to adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease controlled by maintenance infliximab: prospective randomised SWITCH trial. Gut 2012; 61(2):229–234. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300755

- Saha S. Medication management in the pregnant IBD patient. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(5):667–669. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.22

- Ananthakrishnan AN, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Clinician’s Guide. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2017. doi:10.1002/9781119077633

- Shihab Z, Yeomans ND, De Cruz P. Anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha therapies and inflammatory bowel disease pregnancy outcomes: a meta-analysis. J Crohns Colitis 2016; 10(8):979–988. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv234

- Narula N, Al-Dabbagh, Dhillon A, Sands BE, Marshall JK. Anti-TNF alpha therapies are safe during pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2014; 20(10):1862–1869. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000092

- Nielsen OH, Loftus EV Jr, Jess T. Safety of TNF-alpha inhibitors during IBD pregnancy: a systematic review. BMC Med 2013; 11:174. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-174

- Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Domenech E, et al. Safety of thiopurines and anti-TNF-alpha drugs during pregnancy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(3):433–440. doi:10.1038/ajg.2012.430

- Nguyen GC, Seow CH, Maxwell C, et al; IBD in Pregnancy Consensus Group; Canadian Association of Gastroenterology. The Toronto consensus statements for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in pregnancy. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(3):734–757.e1. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2015.12.003

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro, M. Safety of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy and breastfeeding in women with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(9):1426–1438. doi:10.1038/ajg.2013.171

- Chaparro M, Verreth A, Lobaton T, et al. Long-term safety of in utero exposure to anti-TNF alpha drugs for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: results from the multicenter European TEDDY Study. Am J Gastroenterol 2018; 113(3):396–403. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.501

- de Lima A, Zelinkova Z, van der Ent C, Steegers EA, van der Woude CJ. Tailored anti-TNF therapy during pregnancy in patients with IBD: maternal and fetal safety. Gut 2016; 65(8):1261–1268. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309321

- Van Assche G, Vermeire S, Ballet V, et al. Switch to adalimumab in patients with Crohn’s disease controlled by maintenance infliximab: prospective randomised SWITCH trial. Gut 2012; 61(2):229–234. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300755

- Saha S. Medication management in the pregnant IBD patient. Am J Gastroenterol 2017; 112(5):667–669. doi:10.1038/ajg.2017.22

In reply: Vitamin B12 deficiency

In Reply: We thank Dr. Phillips for his inquiry.

In general, serum vitamin B12 concentrations vary greatly, and we acknowledge that serum vitamin B12 may be normal in up to 5% of patients with documented B12 deficiency.1 In a prospective study of 1,599 patients, Matchar et al2 demonstrated that a single vitamin B12 level less than 200 pg/mL had a specificity greater than 95% at predicting vitamin B12 deficiency.2 We acknowledge that additional metabolite testing is necessary in equivocal cases in which the vitamin B12 level is between 200 and 300 pg/mL, which is often considered to be the normal range, but the patient has symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency such as dementia and unexplained macrocytosis, and neurologic symptoms.3

Based on the patient’s symptoms of neuropathy and fatigue in conjunction with a vitamin B12 level well below 200 pg/mL, we believe that the diagnosis can be made.2,3 Nonetheless, although we did not mention it in our article, we did indeed send for a methylmalonic acid measurement at the time of the initial evaluation, and the level was elevated at 396 nmol/L (normal 87–318 nmol/L), further confirming her vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Naurath HJ, Joosten E, Riezler R, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Lindenbaum J. Effects of vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin B6 supplements in elderly people with normal serum vitamin concentrations. Lancet 1995; 346:85–89.

- Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Millington DS, Feussner JR. Performance of the serum cobalamin assay for diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Am J Med Sci 1994; 308:276–283.

- Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Eng J Med 2013; 368:149–160.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Phillips for his inquiry.

In general, serum vitamin B12 concentrations vary greatly, and we acknowledge that serum vitamin B12 may be normal in up to 5% of patients with documented B12 deficiency.1 In a prospective study of 1,599 patients, Matchar et al2 demonstrated that a single vitamin B12 level less than 200 pg/mL had a specificity greater than 95% at predicting vitamin B12 deficiency.2 We acknowledge that additional metabolite testing is necessary in equivocal cases in which the vitamin B12 level is between 200 and 300 pg/mL, which is often considered to be the normal range, but the patient has symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency such as dementia and unexplained macrocytosis, and neurologic symptoms.3

Based on the patient’s symptoms of neuropathy and fatigue in conjunction with a vitamin B12 level well below 200 pg/mL, we believe that the diagnosis can be made.2,3 Nonetheless, although we did not mention it in our article, we did indeed send for a methylmalonic acid measurement at the time of the initial evaluation, and the level was elevated at 396 nmol/L (normal 87–318 nmol/L), further confirming her vitamin B12 deficiency.

In Reply: We thank Dr. Phillips for his inquiry.

In general, serum vitamin B12 concentrations vary greatly, and we acknowledge that serum vitamin B12 may be normal in up to 5% of patients with documented B12 deficiency.1 In a prospective study of 1,599 patients, Matchar et al2 demonstrated that a single vitamin B12 level less than 200 pg/mL had a specificity greater than 95% at predicting vitamin B12 deficiency.2 We acknowledge that additional metabolite testing is necessary in equivocal cases in which the vitamin B12 level is between 200 and 300 pg/mL, which is often considered to be the normal range, but the patient has symptoms of vitamin B12 deficiency such as dementia and unexplained macrocytosis, and neurologic symptoms.3

Based on the patient’s symptoms of neuropathy and fatigue in conjunction with a vitamin B12 level well below 200 pg/mL, we believe that the diagnosis can be made.2,3 Nonetheless, although we did not mention it in our article, we did indeed send for a methylmalonic acid measurement at the time of the initial evaluation, and the level was elevated at 396 nmol/L (normal 87–318 nmol/L), further confirming her vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Naurath HJ, Joosten E, Riezler R, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Lindenbaum J. Effects of vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin B6 supplements in elderly people with normal serum vitamin concentrations. Lancet 1995; 346:85–89.

- Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Millington DS, Feussner JR. Performance of the serum cobalamin assay for diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Am J Med Sci 1994; 308:276–283.

- Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Eng J Med 2013; 368:149–160.

- Naurath HJ, Joosten E, Riezler R, Stabler SP, Allen RH, Lindenbaum J. Effects of vitamin B12, folate, and vitamin B6 supplements in elderly people with normal serum vitamin concentrations. Lancet 1995; 346:85–89.

- Matchar DB, McCrory DC, Millington DS, Feussner JR. Performance of the serum cobalamin assay for diagnosis of cobalamin deficiency. Am J Med Sci 1994; 308:276–283.

- Stabler SP. Clinical practice. Vitamin B12 deficiency. N Eng J Med 2013; 368:149–160.

An unusual cause of vitamin B12 and iron deficiency

A 76-year-old woman visiting from Ethiopia presented for further evaluation of concomitant iron and vitamin B12 deficiency anemia that had developed over the previous 6 months. During that time, she had complained of ongoing fatigue and increasing paresthesias in the hands and feet.

At presentation, her hemoglobin concentration was 7.8 g/dL (reference range 11.5–15), with a mean corpuscular volume of 81.8 fL (81.5–97.0). These values were down from her baseline hemoglobin of 12 g/dL and corpuscular volume of 85.8 recorded more than 1 year ago. Serum studies showed an iron concentration of 21 µg/dL (37–170), ferritin 3 ng/mL (10–107), and percent saturation of transferrin 5% (20%–55%). Also noted was a low vitamin B12 level of 108 pg/mL (180–1,241 pg/mL). She had no overt signs of gastrointestinal blood loss. She did not report altered bowel habits or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Given her country of origin, she was sent for initial stool testing for ova and parasites, which was unrevealing.

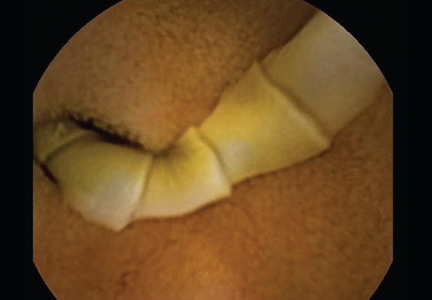

She underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, which revealed no underlying cause of her iron deficiency or vitamin B12 insufficiency. But further evaluation with capsule endoscopy showed evidence of a tapeworm in the distal duodenum (Figure 1).

She was given praziquantel in a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg. Repeat stool culture 1 month later showed no evidence of tapeworm infection, and at follow-up 3 months later, her hemoglobin had recovered to 13.2 g/dL with a corpuscular volume of 87.6 fL and no residual vitamin B12 or iron deficiency. She reported complete resolution of fatigue and of paresthesias of the hands and feet.

DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM LATUM

The appearance on capsule endoscopy indicated Diphyllobothrium latum as the likely parasite. This tapeworm is acquired by ingesting undercooked or raw fish. Infection is most common in Northern Europe but has been reported in Africa.1

As it grows, the tapeworm develops chains of segments and can reach a length of 1 to 15 meters.1 In humans, it typically resides in the small intestine. Most patients are asymptomatic or have moderate nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. A key differentiating aspect of D latum infection is vitamin B12 deficiency caused by consumption of the vitamin by the parasite, as well as by parasite-mediated dissociation of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex, thus making the vitamin unavailable to the host.

Up to 40% of people infected with D latum develop low levels of vitamin B12, and 2% develop symptomatic megaloblastic anemia.2 Iron deficiency anemia is uncommon but has been reported.3 In our patient, the concomitant iron deficiency was probably secondary to involvement of the duodenum, where a significant amount of dietary iron is absorbed.

The diagnosis is typically established by stool testing for ova and parasites. When stool samples do not reveal a cause of the symptoms, as in this patient, endoscopy can be used. Capsule endoscopy has not been widely used in the diagnosis of intestinal helminth infection, although reports exist describing the use of capsule endoscopy to detect intestinal parasites. Notably, as in this case, intestinal parasite infection is occasionally found during investigations of anemia and vitamin deficiencies of unknown cause.4

As in our patient, treatment of infection with this species of tapeworm typically involves a single oral dose of praziquantel; this off-label use has been shown to lead to resolution of symptoms in nearly all patients treated.5

- Schantz PM. Tapeworms (cestodiasis). Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:637–653.

- Scholz T, Garcia HH, Kuchta R, Wicht B. Update on the human broad tapeworm (genus Diphyllobothrium), including clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22:146–160,

- Stanciu C, Trifan A, Singeap AM, Sfarti C, Cojocariu C, Luca M. Diphyllobothrium latum identified by capsule endoscopy—an unusual cause of iron-deficiency anemia. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2009; 18:142.

- Soga K, Handa O, Yamada M, et al. In vivo imaging of intestinal helminths by capsule endoscopy. Parasitol Int 2014; 63:221–228.

- Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 3rd edition. Treatment guidelines from the Medical Letter 2010. The Medical Letter, Inc., New Rochelle, NY.

A 76-year-old woman visiting from Ethiopia presented for further evaluation of concomitant iron and vitamin B12 deficiency anemia that had developed over the previous 6 months. During that time, she had complained of ongoing fatigue and increasing paresthesias in the hands and feet.

At presentation, her hemoglobin concentration was 7.8 g/dL (reference range 11.5–15), with a mean corpuscular volume of 81.8 fL (81.5–97.0). These values were down from her baseline hemoglobin of 12 g/dL and corpuscular volume of 85.8 recorded more than 1 year ago. Serum studies showed an iron concentration of 21 µg/dL (37–170), ferritin 3 ng/mL (10–107), and percent saturation of transferrin 5% (20%–55%). Also noted was a low vitamin B12 level of 108 pg/mL (180–1,241 pg/mL). She had no overt signs of gastrointestinal blood loss. She did not report altered bowel habits or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Given her country of origin, she was sent for initial stool testing for ova and parasites, which was unrevealing.

She underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, which revealed no underlying cause of her iron deficiency or vitamin B12 insufficiency. But further evaluation with capsule endoscopy showed evidence of a tapeworm in the distal duodenum (Figure 1).

She was given praziquantel in a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg. Repeat stool culture 1 month later showed no evidence of tapeworm infection, and at follow-up 3 months later, her hemoglobin had recovered to 13.2 g/dL with a corpuscular volume of 87.6 fL and no residual vitamin B12 or iron deficiency. She reported complete resolution of fatigue and of paresthesias of the hands and feet.

DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM LATUM

The appearance on capsule endoscopy indicated Diphyllobothrium latum as the likely parasite. This tapeworm is acquired by ingesting undercooked or raw fish. Infection is most common in Northern Europe but has been reported in Africa.1

As it grows, the tapeworm develops chains of segments and can reach a length of 1 to 15 meters.1 In humans, it typically resides in the small intestine. Most patients are asymptomatic or have moderate nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. A key differentiating aspect of D latum infection is vitamin B12 deficiency caused by consumption of the vitamin by the parasite, as well as by parasite-mediated dissociation of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex, thus making the vitamin unavailable to the host.

Up to 40% of people infected with D latum develop low levels of vitamin B12, and 2% develop symptomatic megaloblastic anemia.2 Iron deficiency anemia is uncommon but has been reported.3 In our patient, the concomitant iron deficiency was probably secondary to involvement of the duodenum, where a significant amount of dietary iron is absorbed.

The diagnosis is typically established by stool testing for ova and parasites. When stool samples do not reveal a cause of the symptoms, as in this patient, endoscopy can be used. Capsule endoscopy has not been widely used in the diagnosis of intestinal helminth infection, although reports exist describing the use of capsule endoscopy to detect intestinal parasites. Notably, as in this case, intestinal parasite infection is occasionally found during investigations of anemia and vitamin deficiencies of unknown cause.4

As in our patient, treatment of infection with this species of tapeworm typically involves a single oral dose of praziquantel; this off-label use has been shown to lead to resolution of symptoms in nearly all patients treated.5

A 76-year-old woman visiting from Ethiopia presented for further evaluation of concomitant iron and vitamin B12 deficiency anemia that had developed over the previous 6 months. During that time, she had complained of ongoing fatigue and increasing paresthesias in the hands and feet.

At presentation, her hemoglobin concentration was 7.8 g/dL (reference range 11.5–15), with a mean corpuscular volume of 81.8 fL (81.5–97.0). These values were down from her baseline hemoglobin of 12 g/dL and corpuscular volume of 85.8 recorded more than 1 year ago. Serum studies showed an iron concentration of 21 µg/dL (37–170), ferritin 3 ng/mL (10–107), and percent saturation of transferrin 5% (20%–55%). Also noted was a low vitamin B12 level of 108 pg/mL (180–1,241 pg/mL). She had no overt signs of gastrointestinal blood loss. She did not report altered bowel habits or use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.

Given her country of origin, she was sent for initial stool testing for ova and parasites, which was unrevealing.

She underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy, which revealed no underlying cause of her iron deficiency or vitamin B12 insufficiency. But further evaluation with capsule endoscopy showed evidence of a tapeworm in the distal duodenum (Figure 1).

She was given praziquantel in a single oral dose of 10 mg/kg. Repeat stool culture 1 month later showed no evidence of tapeworm infection, and at follow-up 3 months later, her hemoglobin had recovered to 13.2 g/dL with a corpuscular volume of 87.6 fL and no residual vitamin B12 or iron deficiency. She reported complete resolution of fatigue and of paresthesias of the hands and feet.

DIPHYLLOBOTHRIUM LATUM

The appearance on capsule endoscopy indicated Diphyllobothrium latum as the likely parasite. This tapeworm is acquired by ingesting undercooked or raw fish. Infection is most common in Northern Europe but has been reported in Africa.1

As it grows, the tapeworm develops chains of segments and can reach a length of 1 to 15 meters.1 In humans, it typically resides in the small intestine. Most patients are asymptomatic or have moderate nonspecific symptoms such as abdominal pain and diarrhea. A key differentiating aspect of D latum infection is vitamin B12 deficiency caused by consumption of the vitamin by the parasite, as well as by parasite-mediated dissociation of the vitamin B12-intrinsic factor complex, thus making the vitamin unavailable to the host.

Up to 40% of people infected with D latum develop low levels of vitamin B12, and 2% develop symptomatic megaloblastic anemia.2 Iron deficiency anemia is uncommon but has been reported.3 In our patient, the concomitant iron deficiency was probably secondary to involvement of the duodenum, where a significant amount of dietary iron is absorbed.

The diagnosis is typically established by stool testing for ova and parasites. When stool samples do not reveal a cause of the symptoms, as in this patient, endoscopy can be used. Capsule endoscopy has not been widely used in the diagnosis of intestinal helminth infection, although reports exist describing the use of capsule endoscopy to detect intestinal parasites. Notably, as in this case, intestinal parasite infection is occasionally found during investigations of anemia and vitamin deficiencies of unknown cause.4

As in our patient, treatment of infection with this species of tapeworm typically involves a single oral dose of praziquantel; this off-label use has been shown to lead to resolution of symptoms in nearly all patients treated.5

- Schantz PM. Tapeworms (cestodiasis). Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:637–653.

- Scholz T, Garcia HH, Kuchta R, Wicht B. Update on the human broad tapeworm (genus Diphyllobothrium), including clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22:146–160,

- Stanciu C, Trifan A, Singeap AM, Sfarti C, Cojocariu C, Luca M. Diphyllobothrium latum identified by capsule endoscopy—an unusual cause of iron-deficiency anemia. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2009; 18:142.

- Soga K, Handa O, Yamada M, et al. In vivo imaging of intestinal helminths by capsule endoscopy. Parasitol Int 2014; 63:221–228.

- Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 3rd edition. Treatment guidelines from the Medical Letter 2010. The Medical Letter, Inc., New Rochelle, NY.

- Schantz PM. Tapeworms (cestodiasis). Gastroenterol Clin North Am 1996; 25:637–653.

- Scholz T, Garcia HH, Kuchta R, Wicht B. Update on the human broad tapeworm (genus Diphyllobothrium), including clinical relevance. Clin Microbiol Rev 2009; 22:146–160,

- Stanciu C, Trifan A, Singeap AM, Sfarti C, Cojocariu C, Luca M. Diphyllobothrium latum identified by capsule endoscopy—an unusual cause of iron-deficiency anemia. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2009; 18:142.

- Soga K, Handa O, Yamada M, et al. In vivo imaging of intestinal helminths by capsule endoscopy. Parasitol Int 2014; 63:221–228.

- Drugs for Parasitic Infections. 3rd edition. Treatment guidelines from the Medical Letter 2010. The Medical Letter, Inc., New Rochelle, NY.

Ulcerative colitis and an abnormal cholangiogram

A 49-year-old man has had ulcerative colitis for more than 30 years. It is well controlled with sulfasalazine (Azulfidine). Now, he has come to see his primary care physician because for the past 3 months he has had mild, intermittent pain in his right upper abdominal quadrant.

His physical examination is normal. Routine laboratory testing shows the following:

- Hemoglobin 14.2 g/dL (reference range 13.5–17.5)

- White blood cell count 6.7 × 109/L (3.5–10.5)

- Platelet count 279 × 109/L (150–450)

- Alkaline phosphatase 387 U/L (45–115)

- Total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL (0.1–1.0)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 35 U/L (35–48)

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 30 U/L (7–55).

WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS?

1. Based on this information, which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

The most likely diagnosis is primary sclerosing cholangitis, a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by diffuse inflammatory destruction of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver failure. Its cause is unknown, but it is likely the result of acquired exposures interacting with predisposing host factors. Current diagnostic criteria include:

- Characteristic cholangiographic abnormalities of the biliary tree

- Compatible clinical and biochemical findings (typically cholestasis with elevated alkaline phosphatase levels for at least 6 months)

- Exclusion of causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis: secondary sclerosing cholangitis is characterized by a similar multifocal biliary stricturing process, but with an identifiable cause such as long-term biliary obstruction, surgical biliary trauma, or recurrent pancreatitis.1

At presentation, the most common liver enzyme abnormality is an elevated alkaline phosphatase level, often three or four times the normal level.2 In contrast, aminotransferase levels are only modestly elevated, less than three times the upper limit of normal.3 At the time of diagnosis, serum bilirubin levels are normal in 60% of patients.4

Two large epidemiologic studies (one from Olmsted County, MN,5 the other from Swansea, Wales, UK6) estimated the age-adjusted incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis to be 0.9 per 100,000 individuals. The median age of the patients at onset was in the 30s or 40s, and most were men. At 10 years, an estimated 65% were still alive and had not undergone liver transplantation—a significantly lower percentage than in age- and sex-matched populations.

It is estimated that more than 70% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis also have inflammatory bowel disease.5 In fact, the most common presentation of primary sclerosing cholangitis is asymptomatic inflammatory bowel disease and persistently elevated alkaline phosphatase—usually first noted on routine biochemical screening, as in our patient.

Imaging of the biliary tree is essential for the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Typical findings on cholangiography include multifocal stricturing and beading, usually involving both the intrahepatic and the extrahepatic biliary systems, as in our patient (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is considered the gold standard imaging test, but recent studies have shown that magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an acceptable noninvasive substitute,7 and it may cost less per diagnosis.8

Liver biopsy alone is generally nondiagnostic because the histologic changes are quite variable in different segments of the same liver. The classic “onion-skin fibrosis” of primary sclerosing cholangitis is seen in fewer than 10% of biopsy specimens.9

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is chronic and is characterized by circulating autoantibodies and high serum globulin concentrations.10 Its presentation is heterogeneous, varying from no symptoms to nonspecific symptoms of malaise, fatigue, abdominal pain, itching, and arthralgia. Generally, elevations in aminotransferases are much more prominent than abnormalities in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels10—unlike the pattern in our patient.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis is diagnosed if the patient has at least two of these three clinical criteria:

- Biochemical evidence of cholestasis, with elevation of alkaline phosphatase for at least 6 months

- Antimitochondrial antibody

- Histologic evidence of nonsuppurative cholangitis and destruction of small or medium-sized bile ducts.11

In patients who lack antimitochondrial antibody, liver biopsy is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Given that primary biliary cirrhosis involves only small and medium-sized bile ducts, cholangiography is usually normal unless the patient has advanced cirrhosis.

Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia

Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia is a rare condition of unknown cause that involves the progressive destruction of segments of the small bile ducts inside the liver (“small-duct” biliary disease).12 Laboratory findings reveal a cholestatic pattern of liver injury, but biopsy samples show no features diagnostic or suggestive of another biliary disease; cholangiography is typically normal.12,13

ASSOCIATION WITH INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

2. Which statement best characterizes inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Crohn disease of the small bowel is the most common form

- Liver disease often precedes the bowel disease

- Treating the underlying bowel disease improves the long-term prognosis for the liver condition

- Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis are at higher risk of colonic dysplasia than patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone

From 70% to 80% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis also have inflammatory bowel disease, usually chronic ulcerative colitis.14,15 Conversely, 2.4% to 4% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 1.4% to 3.4% of patients with Crohn disease have primary sclerosing cholangitis.1

Typically, the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is made 8 to 10 years before the diagnosis of liver disease, although cases have also been reported to occur years after the diagnosis of cholangitis.15,16

No association between the severity of bowel disease and liver disease has been reported, and treating the inflammatory bowel disease does not alter the natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Particularly, proctocolectomy, the most aggressive treatment for chronic ulcerative colitis, appears to have no effect on the course of the cholangitis.17

In patients with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis, the risk of colonic dysplasia is higher than in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone.18 Recent studies have predicted that the risk of colorectal carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease is as high as 25% after 10 years.19,20 Therefore, annual colonoscopy with surveillance biopsy is recommended in patients with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis, since screening and early detection improve survival rates.15

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

After being diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, the patient inquires about ongoing medical therapy and long-term prognosis.

3. Which is the only life-prolonging therapy for primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Methotrexate (Trexall)

- Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (Actigall) at a standard dosage (13–15 mg/kg/day)

- UDCA at a high dosage (20–30 mg/kg/day)

- Liver transplantation

Drug therapy has not been shown to improve the prognosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

In randomized placebo-controlled trials, penicillamine (Depen), colchicine (Colcrys), methotrexate, and UDCA (13–15 mg/kg per day) failed to show efficacy.21–23

In pilot studies, high-dose UDCA (20 to 30 mg/kg/day) initially appeared to bring an improvement in survival probability, with trends toward histologic improvement,24,25 but larger randomized placebo-controlled trials found no improvement in symptoms, quality of life, survival rates, or risk of cholangiocarcinoma with high-dose UDCA.26,27 In fact, in 5 years of follow-up, patients on high-dose UDCA had a risk of death or transplantation two times higher than with placebo.27 One study indicated UDCA may decrease the incidence of colonic dysplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis.28 However, more prospective studies are required to better define the routine use of UDCA as a prophylactic agent.

Liver transplantation remains the most effective treatment for primary sclerosing cholangitis, and it improves the rate of survival.29 Nevertheless, about 20% of patients who undergo transplantation have a recurrence of cholangitis, and it may recur earlier after living-donor liver transplantation, particularly when the graft is from a biologically related donor.30 Proposed risk factors for recurrence include inflammatory bowel disease, prolonged ischemia time, the number of cellular rejection events, prior biliary surgery, cytomegalovirus infection, and lymphocytotoxic cross-match.31

4. In addition to cirrhosis and cholangitis, which of the following is a potential long-term complication of primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Colon cancer

- Cholangiocarcinoma

- Osteoporosis

- Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency

- All of the above

All are potential long-term complications.

Colon cancer. Concomitant chronic ulcerative colitis puts the patient at a higher risk of colonic dysplasia compared with patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone.18 According to recent studies of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease, 19,20 the risk of colorectal carcinoma after 10 years of disease is as high as 25%.

Cholangiocarcinoma. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is considered a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, with an estimated 10-year cumulative incidence of 7% to 9%.1,20 In a retrospective study of 30 patients,32 the median survival was 5 months from the time of diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma; at the time of diagnosis approximately 19 patients (63%) had metastatic disease.

At present, early detection of cholangiocarcinoma is hampered by the low sensitivity and specificity of standard diagnostic approaches. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 has been used as a marker, but it has questionable accuracy, since elevations of this antigen can also be a result of pancreatic malignancy and bacterial cholangitis. However, cholangiocarcinoma should be suspected when patients present with progressive jaundice, weight loss, abdominal discomfort, and a sudden rise in carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Conventional ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) have poor sensitivity for detecting this malignancy. ERCP with biliary brushings should be considered when evaluating for biliary malignancy. New diagnostic methods such as digitized image analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization on biliary brushings offer promise to evaluate bile duct lesions for cellular aneuploidy and chromosomal aberrations, which may improve the detection of cholangiocarcinoma.33 A recent large-scale study of nearly 500 patients showed that fluorescence in situ hybridization had a higher sensitivity (42.9%) than routine cytology (20.1%) with identical specificity (99.6%) for malignancy.34

Metabolic bone disease, usually osteoporosis rather than osteomalacia, is relatively common and is an important complication of primary sclerosing cholangitis.35 Patients with osteoporosis should be treated with vitamin D and calcium supplementation. Bisphosphonates have been used with varying results in primary biliary cirrhosis36 and can be considered in patients with advanced osteoporosis.

Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency is relatively common in primary sclerosing cholangitis, particularly as it progresses to advanced liver disease. Up to 40% of patients have vitamin A deficiency, 14% have vitamin D deficiency, and 2% have vitamin E deficiency.37 Patients can undergo simple oral replacement therapy.

A stone is removed, fever develops

Three years after the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis, the patient develops mild hyperbilirubinemia and undergoes ERCP at his local hospital. A stone is found obstructing the common bile duct and is successfully extracted.

Twenty-four hours after this procedure, he develops severe right-upper-quadrant pain and fever. He is seen at his local emergency department and blood cultures are drawn. He is started on antibiotics and is transferred to Mayo Clinic for further management.

5. In addition to continuing a broad-spectrum antibiotic, which would be the next best step for this patient?

- ERCP

- MRCP

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal CT

The patient’s clinical presentation is consistent with acute bacterial cholangitis. The classic Charcot triad of fever, right-upper-quadrant pain, and jaundice occurs in only 50% to 75% of patients with acute cholangitis.38 In addition to receiving a broad-spectrum antibiotic, patients with bacterial cholangitis require emergency endoscopic evaluation—ERCP—to find and remove stones from the bile ducts and, if necessary, to dilate the biliary strictures to allow adequate drainage.

In our experience, more than 10% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis who undergo ERCP develop complications requiring hospitalization.39 The procedure generally takes longer to perform and the incidence of cholangitis is higher, despite routine antibiotic prophylaxis, in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis than in those without it. However, the overall risk of pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding was similar in patients with or without sclerosing cholangitis.39

MRCP is a promising noninvasive substitute for ERCP in establishing the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.7,8 Unfortunately, as with other noninvasive imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasonography and CT, MRCP does not allow for therapeutic biliary decompression.

The patient undergoes ERCP with stenting

The patient’s acute cholangitis is thought to be a complication of his recent ERCP procedure. He undergoes emergency ERCP with balloon dilation and placement of a temporary left hepatic stent. His fever improves and he is discharged 48 hours later. He completes a 14-day course of antibiotics for Enterococcus faecalis bacteremia. Six weeks later, he undergoes ERCP yet again to remove the stent and tolerates the procedure well without complications.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a progressive cholestatic liver disease of unknown etiology that primarily affects men during the fourth decade of life.

- This condition is strongly associated with inflammatory bowel disease, particularly with ulcerative colitis.

- Cholangiocarcinoma and colon cancer are dreaded complications.

- Liver transplantation is the only life-extending therapy for primary sclerosing cholangitis; however, the condition can recur in the allograft.

- Chapman R, Fevery J, Kalloo A, et al; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Diagnosis and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2010; 51:660–678.

- Silveira MG, Lindor KD. Clinical features and management of primary sclerosing cholangitis. World J Gastroenterol 2008; 14:3338–3349.

- Lee YM, Kaplan MM. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. N Engl J Med 1995; 332:924–933.

- Talwalkar JA, Lindor KD. Primary sclerosing cholangitis. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2005; 11:62–72.

- Bambha K, Kim WR, Talwalkar J, et al. Incidence, clinical spectrum, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis in a United States community. Gastroenterology 2003; 125:1364–1369.

- Kingham JG, Kochar N, Gravenor MB. Incidence, clinical patterns, and outcomes of primary sclerosing cholangitis in South Wales, United Kingdom. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:1929–1930.

- Berstad AE, Aabakken L, Smith HJ, Aasen S, Boberg KM, Schrumpf E. Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance and endoscopic retrograde cholangiography in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:514–520.

- Talwalkar JA, Angulo P, Johnson CD, Petersen BT, Lindor KD. Cost-minimization analysis of MRC versus ERCP for the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2004; 40:39–45.

- Ludwig J, Barham SS, LaRusso NF, Elveback LR, Wiesner RH, McCall JT. Morphologic features of chronic hepatitis associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis. Hepatology 1981; 1:632–640.

- Krawitt EL. Autoimmune hepatitis. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:54–66.

- Lindor KD, Gershwin ME, Poupon R, Kaplan M, Bergasa NV, Heathcote EJ; American Association for Study of Liver Diseases. Primary biliary cirrhosis. Hepatology 2009; 50:291–308.

- Ludwig J, Wiesner RH, LaRusso NF. Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia. A cause of chronic cholestatic liver disease and biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol 1988; 7:193–199.

- Ludwig J. Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia: an update. Mayo Clin Proc 1998; 73:285–291.

- Fausa O, Schrumpf E, Elgjo K. Relationship of inflammatory bowel disease and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Semin Liver Dis 1991; 11:31–39.

- Loftus EV, Aguilar HI, Sandborn WJ, et al. Risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis following orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology 1998; 27:685–690.

- Loftus EV, Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, et al. Risk of colorectal neoplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1996; 110:432–440.

- Cangemi JR, Wiesner RH, Beaver SJ, et al. Effect of proctocolectomy for chronic ulcerative colitis on the natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1989; 96:790–794.

- Broomé U, Löfberg R, Veress B, Eriksson LS. Primary sclerosing cholangitis and ulcerative colitis: evidence for increased neoplastic potential. Hepatology 1995; 22:1404–1408.

- Kornfeld D, Ekbom A, Ihre T. Is there an excess risk for colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis and concomitant primary sclerosing cholangitis? A population based study. Gut 1997; 41:522–525.

- Claessen MM, Vleggaar FP, Tytgat KM, Siersema PD, van Buuren HR. High lifetime risk of cancer in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Hepatol 2009; 50:158–164.

- Lindor KD. Ursodiol for primary sclerosing cholangitis. Mayo Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis-Ursodeoxycholic Acid Study Group. N Engl J Med 1997; 336:691–695.

- Olsson R, Broomé U, Danielsson A, et al. Colchicine treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1995; 108:1199–1203.

- LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH, Ludwig J, MacCarty RL, Beaver SJ, Zinsmeister AR. Prospective trial of penicillamine in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 1988; 95:1036–1042.

- Mitchell SA, Bansi DS, Hunt N, Von Bergmann K, Fleming KA, Chapman RW. A preliminary trial of high-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology 2001; 121:900–907.

- Cullen SN, Rust C, Fleming K, Edwards C, Beuers U, Chapman RW. High dose ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis is safe and effective. J Hepatol 2008; 48:792–800.

- Olsson R, Boberg KM, de Muckadell OS, et al. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid in primary sclerosing cholangitis: a 5-year multicenter, randomized, controlled study. Gastroenterology 2005; 129:1464–1472.

- Lindor KD, Kowdley KV, Luketic VA, et al. High-dose ursodeoxycholic acid for the treatment of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 2009; 50:808–814.

- Tung BY, Emond MJ, Haggitt RC, et al. Ursodiol use is associated with lower prevalence of colonic neoplasia in patients with ulcerative colitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Intern Med 2001; 134:89–95.

- Wiesner RH, Porayko MK, Hay JE, et al. Liver transplantation for primary sclerosing cholangitis: impact of risk factors on outcome. Liver Transpl Surg 1996; 2(suppl 1):99–108..

- Tamura S, Sugawara Y, Kaneko J, Matsui Y, Togashi J, Makuuchi M. Recurrence of primary sclerosing cholangitis after living donor liver transplantation. Liver Int 2007; 27:86–94.

- Gautam M, Cheruvattath R, Balan V. Recurrence of autoimmune liver disease after liver transplantation: a systematic review. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:1813–1824.

- Rosen CB, Nagorney DM, Wiesner RH, Coffey RJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocarcinoma complicating primary sclerosing cholangitis. Ann Surg 1991; 213:21–25.

- Lazaridis KN, Gores GJ. Cholangiocarcinoma. Gastroenterology 2005; 128:1655–1667.

- Fritcher EG, Kipp BR, Halling KC, et al. A multivariable model using advanced cytologic methods for the evaluation of indeterminate pancreatobiliary strictures. Gastroenterology 2009; 136:2180–2186.

- Hay JE, Lindor KD, Wiesner RH, Dickson ER, Krom RA, LaRusso NF. The metabolic bone disease of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology 1991; 14:257–261.

- Guañabens N, Parés A, Ros I, et al. Alendronate is more effective than etidronate for increasing bone mass in osteopenic patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2003; 98:2268–2274.

- Jorgensen RA, Lindor KD, Sartin JS, LaRusso NF, Wiesner RH. Serum lipid and fat-soluble vitamin levels in primary sclerosing cholangitis. J Clin Gastroenterol 1995; 20:215–219.

- Saik RP, Greenburg AG, Farris JM, Peskin GW. Spectrum of cholangitis. Am J Surg 1975; 130:143–150.

- Bangarulingam SY, Gossard AA, Petersen BT, Ott BJ, Lindor KD. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104:855–860.

A 49-year-old man has had ulcerative colitis for more than 30 years. It is well controlled with sulfasalazine (Azulfidine). Now, he has come to see his primary care physician because for the past 3 months he has had mild, intermittent pain in his right upper abdominal quadrant.

His physical examination is normal. Routine laboratory testing shows the following:

- Hemoglobin 14.2 g/dL (reference range 13.5–17.5)

- White blood cell count 6.7 × 109/L (3.5–10.5)

- Platelet count 279 × 109/L (150–450)

- Alkaline phosphatase 387 U/L (45–115)

- Total bilirubin 0.9 mg/dL (0.1–1.0)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 35 U/L (35–48)

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 30 U/L (7–55).

WHAT IS THE DIAGNOSIS?

1. Based on this information, which of the following is the most likely diagnosis?

- Autoimmune hepatitis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Primary biliary cirrhosis

- Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

The most likely diagnosis is primary sclerosing cholangitis, a chronic cholestatic liver disease characterized by diffuse inflammatory destruction of intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts, resulting in fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver failure. Its cause is unknown, but it is likely the result of acquired exposures interacting with predisposing host factors. Current diagnostic criteria include:

- Characteristic cholangiographic abnormalities of the biliary tree

- Compatible clinical and biochemical findings (typically cholestasis with elevated alkaline phosphatase levels for at least 6 months)

- Exclusion of causes of secondary sclerosing cholangitis: secondary sclerosing cholangitis is characterized by a similar multifocal biliary stricturing process, but with an identifiable cause such as long-term biliary obstruction, surgical biliary trauma, or recurrent pancreatitis.1

At presentation, the most common liver enzyme abnormality is an elevated alkaline phosphatase level, often three or four times the normal level.2 In contrast, aminotransferase levels are only modestly elevated, less than three times the upper limit of normal.3 At the time of diagnosis, serum bilirubin levels are normal in 60% of patients.4

Two large epidemiologic studies (one from Olmsted County, MN,5 the other from Swansea, Wales, UK6) estimated the age-adjusted incidence of primary sclerosing cholangitis to be 0.9 per 100,000 individuals. The median age of the patients at onset was in the 30s or 40s, and most were men. At 10 years, an estimated 65% were still alive and had not undergone liver transplantation—a significantly lower percentage than in age- and sex-matched populations.

It is estimated that more than 70% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis also have inflammatory bowel disease.5 In fact, the most common presentation of primary sclerosing cholangitis is asymptomatic inflammatory bowel disease and persistently elevated alkaline phosphatase—usually first noted on routine biochemical screening, as in our patient.

Imaging of the biliary tree is essential for the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Typical findings on cholangiography include multifocal stricturing and beading, usually involving both the intrahepatic and the extrahepatic biliary systems, as in our patient (Figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is considered the gold standard imaging test, but recent studies have shown that magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) is an acceptable noninvasive substitute,7 and it may cost less per diagnosis.8

Liver biopsy alone is generally nondiagnostic because the histologic changes are quite variable in different segments of the same liver. The classic “onion-skin fibrosis” of primary sclerosing cholangitis is seen in fewer than 10% of biopsy specimens.9

Autoimmune hepatitis

Autoimmune hepatitis is chronic and is characterized by circulating autoantibodies and high serum globulin concentrations.10 Its presentation is heterogeneous, varying from no symptoms to nonspecific symptoms of malaise, fatigue, abdominal pain, itching, and arthralgia. Generally, elevations in aminotransferases are much more prominent than abnormalities in bilirubin and alkaline phosphatase levels10—unlike the pattern in our patient.

Primary biliary cirrhosis

Primary biliary cirrhosis is diagnosed if the patient has at least two of these three clinical criteria:

- Biochemical evidence of cholestasis, with elevation of alkaline phosphatase for at least 6 months

- Antimitochondrial antibody

- Histologic evidence of nonsuppurative cholangitis and destruction of small or medium-sized bile ducts.11

In patients who lack antimitochondrial antibody, liver biopsy is necessary to establish the diagnosis. Given that primary biliary cirrhosis involves only small and medium-sized bile ducts, cholangiography is usually normal unless the patient has advanced cirrhosis.

Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia

Idiopathic adulthood ductopenia is a rare condition of unknown cause that involves the progressive destruction of segments of the small bile ducts inside the liver (“small-duct” biliary disease).12 Laboratory findings reveal a cholestatic pattern of liver injury, but biopsy samples show no features diagnostic or suggestive of another biliary disease; cholangiography is typically normal.12,13

ASSOCIATION WITH INFLAMMATORY BOWEL DISEASE

2. Which statement best characterizes inflammatory bowel disease associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Crohn disease of the small bowel is the most common form

- Liver disease often precedes the bowel disease

- Treating the underlying bowel disease improves the long-term prognosis for the liver condition

- Patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis are at higher risk of colonic dysplasia than patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone

From 70% to 80% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis also have inflammatory bowel disease, usually chronic ulcerative colitis.14,15 Conversely, 2.4% to 4% of patients with ulcerative colitis and 1.4% to 3.4% of patients with Crohn disease have primary sclerosing cholangitis.1

Typically, the diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease is made 8 to 10 years before the diagnosis of liver disease, although cases have also been reported to occur years after the diagnosis of cholangitis.15,16

No association between the severity of bowel disease and liver disease has been reported, and treating the inflammatory bowel disease does not alter the natural history of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Particularly, proctocolectomy, the most aggressive treatment for chronic ulcerative colitis, appears to have no effect on the course of the cholangitis.17

In patients with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis, the risk of colonic dysplasia is higher than in patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone.18 Recent studies have predicted that the risk of colorectal carcinoma in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease is as high as 25% after 10 years.19,20 Therefore, annual colonoscopy with surveillance biopsy is recommended in patients with both primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis, since screening and early detection improve survival rates.15

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

After being diagnosed with primary sclerosing cholangitis, the patient inquires about ongoing medical therapy and long-term prognosis.

3. Which is the only life-prolonging therapy for primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Methotrexate (Trexall)

- Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) (Actigall) at a standard dosage (13–15 mg/kg/day)

- UDCA at a high dosage (20–30 mg/kg/day)

- Liver transplantation

Drug therapy has not been shown to improve the prognosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.

In randomized placebo-controlled trials, penicillamine (Depen), colchicine (Colcrys), methotrexate, and UDCA (13–15 mg/kg per day) failed to show efficacy.21–23

In pilot studies, high-dose UDCA (20 to 30 mg/kg/day) initially appeared to bring an improvement in survival probability, with trends toward histologic improvement,24,25 but larger randomized placebo-controlled trials found no improvement in symptoms, quality of life, survival rates, or risk of cholangiocarcinoma with high-dose UDCA.26,27 In fact, in 5 years of follow-up, patients on high-dose UDCA had a risk of death or transplantation two times higher than with placebo.27 One study indicated UDCA may decrease the incidence of colonic dysplasia in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and chronic ulcerative colitis.28 However, more prospective studies are required to better define the routine use of UDCA as a prophylactic agent.

Liver transplantation remains the most effective treatment for primary sclerosing cholangitis, and it improves the rate of survival.29 Nevertheless, about 20% of patients who undergo transplantation have a recurrence of cholangitis, and it may recur earlier after living-donor liver transplantation, particularly when the graft is from a biologically related donor.30 Proposed risk factors for recurrence include inflammatory bowel disease, prolonged ischemia time, the number of cellular rejection events, prior biliary surgery, cytomegalovirus infection, and lymphocytotoxic cross-match.31

4. In addition to cirrhosis and cholangitis, which of the following is a potential long-term complication of primary sclerosing cholangitis?

- Colon cancer

- Cholangiocarcinoma

- Osteoporosis

- Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency

- All of the above

All are potential long-term complications.

Colon cancer. Concomitant chronic ulcerative colitis puts the patient at a higher risk of colonic dysplasia compared with patients with chronic ulcerative colitis alone.18 According to recent studies of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and inflammatory bowel disease, 19,20 the risk of colorectal carcinoma after 10 years of disease is as high as 25%.

Cholangiocarcinoma. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is considered a risk factor for cholangiocarcinoma, with an estimated 10-year cumulative incidence of 7% to 9%.1,20 In a retrospective study of 30 patients,32 the median survival was 5 months from the time of diagnosis of cholangiocarcinoma; at the time of diagnosis approximately 19 patients (63%) had metastatic disease.

At present, early detection of cholangiocarcinoma is hampered by the low sensitivity and specificity of standard diagnostic approaches. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 has been used as a marker, but it has questionable accuracy, since elevations of this antigen can also be a result of pancreatic malignancy and bacterial cholangitis. However, cholangiocarcinoma should be suspected when patients present with progressive jaundice, weight loss, abdominal discomfort, and a sudden rise in carbohydrate antigen 19-9.

Conventional ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) have poor sensitivity for detecting this malignancy. ERCP with biliary brushings should be considered when evaluating for biliary malignancy. New diagnostic methods such as digitized image analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization on biliary brushings offer promise to evaluate bile duct lesions for cellular aneuploidy and chromosomal aberrations, which may improve the detection of cholangiocarcinoma.33 A recent large-scale study of nearly 500 patients showed that fluorescence in situ hybridization had a higher sensitivity (42.9%) than routine cytology (20.1%) with identical specificity (99.6%) for malignancy.34

Metabolic bone disease, usually osteoporosis rather than osteomalacia, is relatively common and is an important complication of primary sclerosing cholangitis.35 Patients with osteoporosis should be treated with vitamin D and calcium supplementation. Bisphosphonates have been used with varying results in primary biliary cirrhosis36 and can be considered in patients with advanced osteoporosis.

Fat-soluble vitamin deficiency is relatively common in primary sclerosing cholangitis, particularly as it progresses to advanced liver disease. Up to 40% of patients have vitamin A deficiency, 14% have vitamin D deficiency, and 2% have vitamin E deficiency.37 Patients can undergo simple oral replacement therapy.

A stone is removed, fever develops

Three years after the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis, the patient develops mild hyperbilirubinemia and undergoes ERCP at his local hospital. A stone is found obstructing the common bile duct and is successfully extracted.

Twenty-four hours after this procedure, he develops severe right-upper-quadrant pain and fever. He is seen at his local emergency department and blood cultures are drawn. He is started on antibiotics and is transferred to Mayo Clinic for further management.

5. In addition to continuing a broad-spectrum antibiotic, which would be the next best step for this patient?

- ERCP

- MRCP

- Abdominal ultrasonography

- Abdominal CT

The patient’s clinical presentation is consistent with acute bacterial cholangitis. The classic Charcot triad of fever, right-upper-quadrant pain, and jaundice occurs in only 50% to 75% of patients with acute cholangitis.38 In addition to receiving a broad-spectrum antibiotic, patients with bacterial cholangitis require emergency endoscopic evaluation—ERCP—to find and remove stones from the bile ducts and, if necessary, to dilate the biliary strictures to allow adequate drainage.

In our experience, more than 10% of patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis who undergo ERCP develop complications requiring hospitalization.39 The procedure generally takes longer to perform and the incidence of cholangitis is higher, despite routine antibiotic prophylaxis, in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis than in those without it. However, the overall risk of pancreatitis, perforation, and bleeding was similar in patients with or without sclerosing cholangitis.39

MRCP is a promising noninvasive substitute for ERCP in establishing the diagnosis of primary sclerosing cholangitis.7,8 Unfortunately, as with other noninvasive imaging studies such as abdominal ultrasonography and CT, MRCP does not allow for therapeutic biliary decompression.

The patient undergoes ERCP with stenting