User login

Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: Pathophysiology and treatment

Ms. V, age 58, presents to the emergency department after falling in the middle of the night while walking to the bathroom. Her medical history includes bipolar I disorder (BDI). According to her granddaughter, Ms. V has been stable on lithium 600 mg twice daily for 1 to 2 years. Her laboratory workup shows a serum creatinine level of 0.93 mg/dL (reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), high sodium (154 mEq/L; reference range 135 to 145 mEq/L), and a lithium level of 0.9 mEq/L (therapeutic range 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L). On Day 2 of admission, Ms. V’s sodium level remains high (152 mEq/L), her urine output is 5 L/d (normal output <2 L/d), and her serum osmolality is high (326 mmol/kg; reference range 275 to 295 mmol/kg).

After additional questioning, Ms. V says for the past 3 weeks she has been urinating approximately 4 times per night and experiencing excessive thirst. Given her laboratory values and physical presentation, a desmopressin challenge test is performed and confirms a diagnosis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (Li-NDI). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) occurs when the kidneys become unresponsive to the action of antidiuretic hormone (ADH; also known as vasopressin).1 The most common cause of NDI is lithium. The prevalence varies from 50% to 73% with long-term lithium use.1,2 It is important to recognize the homeostatic regulation of water prior to understanding Li-NDI. The excretion of water is regulated by ADH. ADH binds to the vasopressin receptors on the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct cells. This stimulates Gs protein and adenylate cyclase, which subsequently increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).1 Eventually, this leads to the activation of protein kinase A and phosphorylation of aquaporin 2 (AQP2) water channels. The AQP2 channels redistribute from storage vesicles to the apical membrane and the membrane becomes permeable to water, allowing for reabsorption.1,3

In Li-NDI, lithium enters the cells of the collecting duct through the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC).1,4 There, lithium inhibits the action of ADH, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) activity, and the generation of cAMP.1,4 It also induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in renal interstitial cells and the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).1,5-8 Lithium may also reduce the amount of AQP2 water channels in the apical membrane of the collecting duct. 1,3 Additionally, polymorphisms of the GSK-3 beta gene can occur, which may be related to differences in the extent of the lithium-induced renal concentrating defect among patients who take lithium.9

Symptoms of Li-NDI include polyuria (ie, urine production >3 L/day) and polydipsia.1 More than 40% of patients with symptomatic Li-NDI experience a significant interference with their daily routine and occupational activities, and may be at risk for severe dehydration with concurrent electrolyte disturbances, resulting in lithium toxicity.1,2 This could especially impact older adults, who may have a diminished thirst sensation and insufficient fluid intake (ie, psychological decompensation, decreased mobility).1,2

Li-NDI is reversible early in treatment; however, it may become irreversible over time.1 The degree of reversibility depends on the stage of kidney damage (ie, functional vs morphological) and/or duration of lithium treatment.7 Even with the discontinuation of lithium, symptoms may persist. Imaging can be used to identify the extent of kidney damage, but given the inconsistent data regarding the reversibility of Li-NDI, it would be difficult to predict if symptoms will resolve.8

Establishing the diagnosis

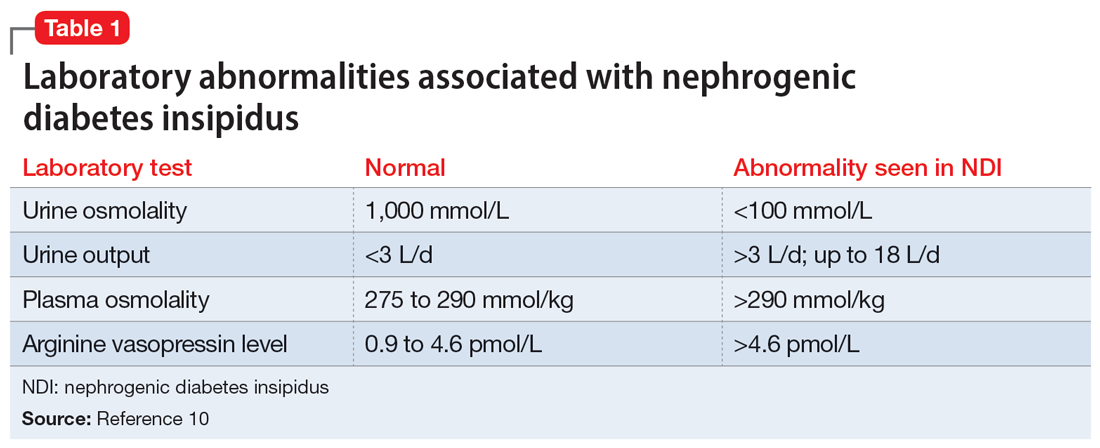

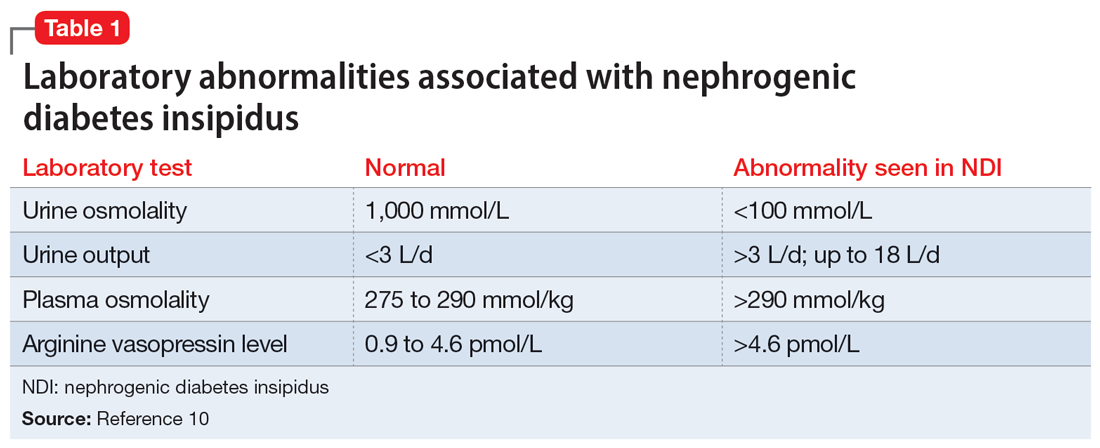

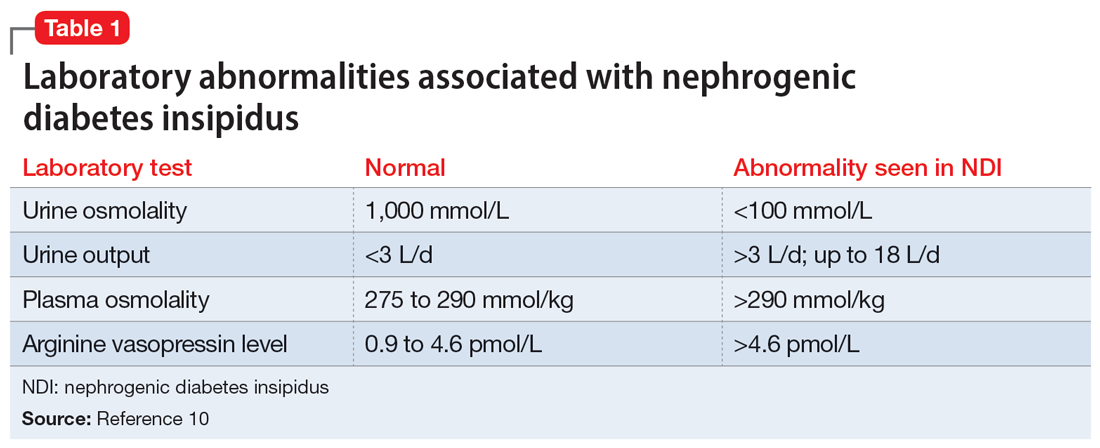

A physical examination and laboratory workup are the first steps in diagnosing and determining the underlying cause of NDI. Table 110 outlines common laboratory abnormalities associated with NDI. Additionally, serum sodium levels can be used to determine water balance; hypernatremia is often seen in cases of NDI.10 Water deprivation tests are useful for diagnosing diabetes insipidus and allow for differentiation of nephrogenic vs central diabetes insipidus.10 Once the patient is water-deprived for ≥4 hours, a single 5-unit dose of subcutaneous desmopressin may be administered. In Li-NDI, the urine often remains dilute with urine osmolality levels <200 mmol/kg, even after administration of exogenous arginine vasopressin.10

Several treatment options

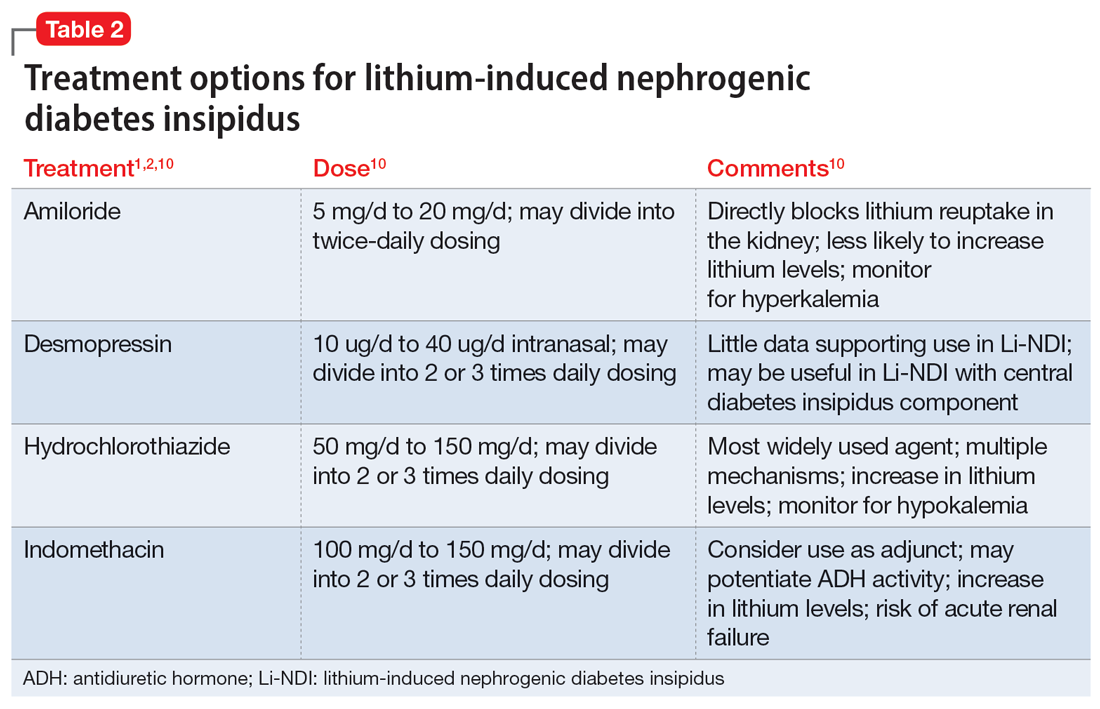

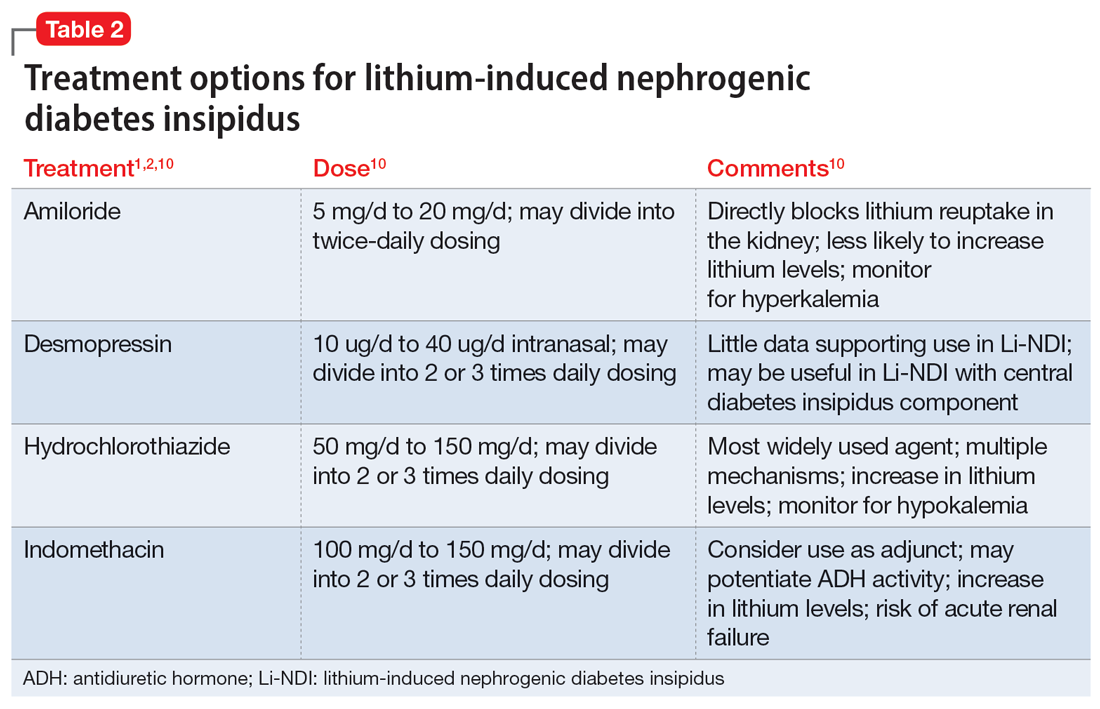

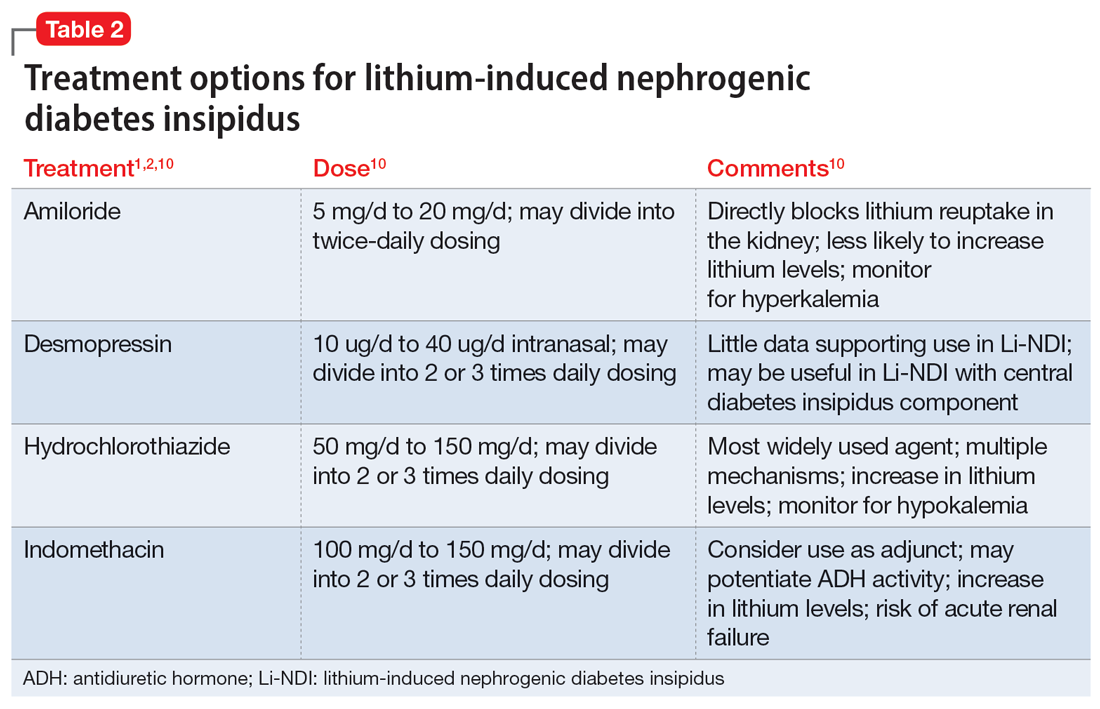

In many cases, Li-NDI symptoms can be reduced by using the lowest effective dose of lithium, switching to a once-daily formulation, or discontinuing therapy. Some patients may find relief from certain diuretics, such as amiloride. Thiazide diuretics can also be used but may require a ≥50% reduction in lithium dose. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, such as indomethacin, in combination with diuretics, have been found to be effective by increasing the concentration of urine.1,2Table 21,2,10 summarizes potential treatment options.

Continue to: Amiloride has the most...

Amiloride has the most supporting evidence in the treatment of Li-NDI. A potassium-sparing diuretic, amiloride works by blocking the ENaC in the distal and collecting duct. Blocking the ENaC inhibits uptake of lithium into the principal cells of the collecting duct within the kidney. Research has shown that amiloride can be effective in treating existing Li-NDI, but there is a lack of evidence supporting its preventative effects.1

Thiazide diuretics work by blocking the sodium-chloride cotransporter in the distal tubules of the kidney. They also upregulate the AQP2 water channels.1 Research has shown that sodium replacement counteracts the antidiuretic effect of thiazide diuretics; limitations in dietary sodium intake may be necessary for treatment efficacy.1

Within the kidneys, PGE2 inhibits adenyl cyclase and diminishes water permeability.10 This causes water to be excreted in urine rather than be reabsorbed.10 Indomethacin blocks PGE2 activity and increases water reabsorption in the collecting ducts, and sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle.10 This mechanism can lead to increased lithium reabsorption, which may precipitate toxicity. Research has shown increases in lithium levels by as much as 59% in addition to the risk of causing acute renal failure, especially in older adults.10 Due to these risks, indomethacin should not be considered a first-line treatment for Li-NDI.

Overall, several medications have shown benefits in the treatment of Li-NDI, with amiloride having the most data. There are currently no medications with sufficient evidence to support prophylactic use.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. V’s treatment team initiates amiloride 5 mg/d. They increase the dose to 10 mg/d after 2 days, and Ms. V’s hypernatremia resolves as her serum sodium normalizes to 142 mEq/L. Her urinary output also decreases to <3 L/d. Throughout treatment, Ms. V continues taking lithium carbonate to prevent destabilization of her BDI. The team subsequently discharges her, and she has been stable for the past 6 months.

Related Resources

- Andreasen A, Ellingrod V. Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: prevention and management. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):42-45.

- Zhang P, Gandhi H, Kassis N. Lithium-induced nephropathy; one medication with multiple side effects: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):309. doi:10.1186/s12882-022-02934-0

Drug Brand Names

Amiloride • Midamor

Desmopressin • DDAVP

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide

Indomethacin • Indocin, Tivorbex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

1. Schoot TS, Molmans THJ, Grootens KP, et al. Systematic review and practical guideline from the prevention and management of renal side effects of lithium therapy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:16-32.

2. Lithium induced diabetes insipidus. DiabetesInsipidus.org. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://diabetesinsipidus.org/lithium-induced-diabetes-insipidus

3. Rej S, Segal M, Low NC, et al. The McGill geriatric lithium-induced diabetes insipidus clinical study (McGLIDICS). Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(6):327-334.

4. Christensen BM, Zuber AM, Loffing J, et al. alphaENaC-mediated lithium absorption promotes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):253-261.

5. Bendz H, Aurell M, Balldin J, et al. Kidney damage in long-term lithium patients: a cross sectional study of patients with 15 years or more on lithium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(9):1250-1254.

6. Bendz H. Kidney function in a selected lithium population. A prospective, controlled, lithium-withdrawal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;72(5):451-463.

7. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28.

8. Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, et al. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):626-637.

9. Bucht G, Whalin A. Renal concentrating capacity in long-term lithium treatment and after withdrawal of lithium. Acta Med Scand. 1980;207(4):309-314.

10. Finch CK, Brooks TWA, Yam P, et al. Management and treatment of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Therapy. 2005;2(4):669-675. doi:10.1586/14750708.2.4.669

Ms. V, age 58, presents to the emergency department after falling in the middle of the night while walking to the bathroom. Her medical history includes bipolar I disorder (BDI). According to her granddaughter, Ms. V has been stable on lithium 600 mg twice daily for 1 to 2 years. Her laboratory workup shows a serum creatinine level of 0.93 mg/dL (reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), high sodium (154 mEq/L; reference range 135 to 145 mEq/L), and a lithium level of 0.9 mEq/L (therapeutic range 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L). On Day 2 of admission, Ms. V’s sodium level remains high (152 mEq/L), her urine output is 5 L/d (normal output <2 L/d), and her serum osmolality is high (326 mmol/kg; reference range 275 to 295 mmol/kg).

After additional questioning, Ms. V says for the past 3 weeks she has been urinating approximately 4 times per night and experiencing excessive thirst. Given her laboratory values and physical presentation, a desmopressin challenge test is performed and confirms a diagnosis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (Li-NDI). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) occurs when the kidneys become unresponsive to the action of antidiuretic hormone (ADH; also known as vasopressin).1 The most common cause of NDI is lithium. The prevalence varies from 50% to 73% with long-term lithium use.1,2 It is important to recognize the homeostatic regulation of water prior to understanding Li-NDI. The excretion of water is regulated by ADH. ADH binds to the vasopressin receptors on the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct cells. This stimulates Gs protein and adenylate cyclase, which subsequently increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).1 Eventually, this leads to the activation of protein kinase A and phosphorylation of aquaporin 2 (AQP2) water channels. The AQP2 channels redistribute from storage vesicles to the apical membrane and the membrane becomes permeable to water, allowing for reabsorption.1,3

In Li-NDI, lithium enters the cells of the collecting duct through the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC).1,4 There, lithium inhibits the action of ADH, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) activity, and the generation of cAMP.1,4 It also induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in renal interstitial cells and the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).1,5-8 Lithium may also reduce the amount of AQP2 water channels in the apical membrane of the collecting duct. 1,3 Additionally, polymorphisms of the GSK-3 beta gene can occur, which may be related to differences in the extent of the lithium-induced renal concentrating defect among patients who take lithium.9

Symptoms of Li-NDI include polyuria (ie, urine production >3 L/day) and polydipsia.1 More than 40% of patients with symptomatic Li-NDI experience a significant interference with their daily routine and occupational activities, and may be at risk for severe dehydration with concurrent electrolyte disturbances, resulting in lithium toxicity.1,2 This could especially impact older adults, who may have a diminished thirst sensation and insufficient fluid intake (ie, psychological decompensation, decreased mobility).1,2

Li-NDI is reversible early in treatment; however, it may become irreversible over time.1 The degree of reversibility depends on the stage of kidney damage (ie, functional vs morphological) and/or duration of lithium treatment.7 Even with the discontinuation of lithium, symptoms may persist. Imaging can be used to identify the extent of kidney damage, but given the inconsistent data regarding the reversibility of Li-NDI, it would be difficult to predict if symptoms will resolve.8

Establishing the diagnosis

A physical examination and laboratory workup are the first steps in diagnosing and determining the underlying cause of NDI. Table 110 outlines common laboratory abnormalities associated with NDI. Additionally, serum sodium levels can be used to determine water balance; hypernatremia is often seen in cases of NDI.10 Water deprivation tests are useful for diagnosing diabetes insipidus and allow for differentiation of nephrogenic vs central diabetes insipidus.10 Once the patient is water-deprived for ≥4 hours, a single 5-unit dose of subcutaneous desmopressin may be administered. In Li-NDI, the urine often remains dilute with urine osmolality levels <200 mmol/kg, even after administration of exogenous arginine vasopressin.10

Several treatment options

In many cases, Li-NDI symptoms can be reduced by using the lowest effective dose of lithium, switching to a once-daily formulation, or discontinuing therapy. Some patients may find relief from certain diuretics, such as amiloride. Thiazide diuretics can also be used but may require a ≥50% reduction in lithium dose. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, such as indomethacin, in combination with diuretics, have been found to be effective by increasing the concentration of urine.1,2Table 21,2,10 summarizes potential treatment options.

Continue to: Amiloride has the most...

Amiloride has the most supporting evidence in the treatment of Li-NDI. A potassium-sparing diuretic, amiloride works by blocking the ENaC in the distal and collecting duct. Blocking the ENaC inhibits uptake of lithium into the principal cells of the collecting duct within the kidney. Research has shown that amiloride can be effective in treating existing Li-NDI, but there is a lack of evidence supporting its preventative effects.1

Thiazide diuretics work by blocking the sodium-chloride cotransporter in the distal tubules of the kidney. They also upregulate the AQP2 water channels.1 Research has shown that sodium replacement counteracts the antidiuretic effect of thiazide diuretics; limitations in dietary sodium intake may be necessary for treatment efficacy.1

Within the kidneys, PGE2 inhibits adenyl cyclase and diminishes water permeability.10 This causes water to be excreted in urine rather than be reabsorbed.10 Indomethacin blocks PGE2 activity and increases water reabsorption in the collecting ducts, and sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle.10 This mechanism can lead to increased lithium reabsorption, which may precipitate toxicity. Research has shown increases in lithium levels by as much as 59% in addition to the risk of causing acute renal failure, especially in older adults.10 Due to these risks, indomethacin should not be considered a first-line treatment for Li-NDI.

Overall, several medications have shown benefits in the treatment of Li-NDI, with amiloride having the most data. There are currently no medications with sufficient evidence to support prophylactic use.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. V’s treatment team initiates amiloride 5 mg/d. They increase the dose to 10 mg/d after 2 days, and Ms. V’s hypernatremia resolves as her serum sodium normalizes to 142 mEq/L. Her urinary output also decreases to <3 L/d. Throughout treatment, Ms. V continues taking lithium carbonate to prevent destabilization of her BDI. The team subsequently discharges her, and she has been stable for the past 6 months.

Related Resources

- Andreasen A, Ellingrod V. Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: prevention and management. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):42-45.

- Zhang P, Gandhi H, Kassis N. Lithium-induced nephropathy; one medication with multiple side effects: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):309. doi:10.1186/s12882-022-02934-0

Drug Brand Names

Amiloride • Midamor

Desmopressin • DDAVP

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide

Indomethacin • Indocin, Tivorbex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Ms. V, age 58, presents to the emergency department after falling in the middle of the night while walking to the bathroom. Her medical history includes bipolar I disorder (BDI). According to her granddaughter, Ms. V has been stable on lithium 600 mg twice daily for 1 to 2 years. Her laboratory workup shows a serum creatinine level of 0.93 mg/dL (reference range 0.6 to 1.2 mg/dL), high sodium (154 mEq/L; reference range 135 to 145 mEq/L), and a lithium level of 0.9 mEq/L (therapeutic range 0.6 to 1.2 mEq/L). On Day 2 of admission, Ms. V’s sodium level remains high (152 mEq/L), her urine output is 5 L/d (normal output <2 L/d), and her serum osmolality is high (326 mmol/kg; reference range 275 to 295 mmol/kg).

After additional questioning, Ms. V says for the past 3 weeks she has been urinating approximately 4 times per night and experiencing excessive thirst. Given her laboratory values and physical presentation, a desmopressin challenge test is performed and confirms a diagnosis of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (Li-NDI). Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus (NDI) occurs when the kidneys become unresponsive to the action of antidiuretic hormone (ADH; also known as vasopressin).1 The most common cause of NDI is lithium. The prevalence varies from 50% to 73% with long-term lithium use.1,2 It is important to recognize the homeostatic regulation of water prior to understanding Li-NDI. The excretion of water is regulated by ADH. ADH binds to the vasopressin receptors on the basolateral membrane of the collecting duct cells. This stimulates Gs protein and adenylate cyclase, which subsequently increase intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP).1 Eventually, this leads to the activation of protein kinase A and phosphorylation of aquaporin 2 (AQP2) water channels. The AQP2 channels redistribute from storage vesicles to the apical membrane and the membrane becomes permeable to water, allowing for reabsorption.1,3

In Li-NDI, lithium enters the cells of the collecting duct through the epithelial sodium channel (ENaC).1,4 There, lithium inhibits the action of ADH, glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) activity, and the generation of cAMP.1,4 It also induces cyclooxygenase-2 expression in renal interstitial cells and the production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2).1,5-8 Lithium may also reduce the amount of AQP2 water channels in the apical membrane of the collecting duct. 1,3 Additionally, polymorphisms of the GSK-3 beta gene can occur, which may be related to differences in the extent of the lithium-induced renal concentrating defect among patients who take lithium.9

Symptoms of Li-NDI include polyuria (ie, urine production >3 L/day) and polydipsia.1 More than 40% of patients with symptomatic Li-NDI experience a significant interference with their daily routine and occupational activities, and may be at risk for severe dehydration with concurrent electrolyte disturbances, resulting in lithium toxicity.1,2 This could especially impact older adults, who may have a diminished thirst sensation and insufficient fluid intake (ie, psychological decompensation, decreased mobility).1,2

Li-NDI is reversible early in treatment; however, it may become irreversible over time.1 The degree of reversibility depends on the stage of kidney damage (ie, functional vs morphological) and/or duration of lithium treatment.7 Even with the discontinuation of lithium, symptoms may persist. Imaging can be used to identify the extent of kidney damage, but given the inconsistent data regarding the reversibility of Li-NDI, it would be difficult to predict if symptoms will resolve.8

Establishing the diagnosis

A physical examination and laboratory workup are the first steps in diagnosing and determining the underlying cause of NDI. Table 110 outlines common laboratory abnormalities associated with NDI. Additionally, serum sodium levels can be used to determine water balance; hypernatremia is often seen in cases of NDI.10 Water deprivation tests are useful for diagnosing diabetes insipidus and allow for differentiation of nephrogenic vs central diabetes insipidus.10 Once the patient is water-deprived for ≥4 hours, a single 5-unit dose of subcutaneous desmopressin may be administered. In Li-NDI, the urine often remains dilute with urine osmolality levels <200 mmol/kg, even after administration of exogenous arginine vasopressin.10

Several treatment options

In many cases, Li-NDI symptoms can be reduced by using the lowest effective dose of lithium, switching to a once-daily formulation, or discontinuing therapy. Some patients may find relief from certain diuretics, such as amiloride. Thiazide diuretics can also be used but may require a ≥50% reduction in lithium dose. Nonsteroid anti-inflammatory drugs, such as indomethacin, in combination with diuretics, have been found to be effective by increasing the concentration of urine.1,2Table 21,2,10 summarizes potential treatment options.

Continue to: Amiloride has the most...

Amiloride has the most supporting evidence in the treatment of Li-NDI. A potassium-sparing diuretic, amiloride works by blocking the ENaC in the distal and collecting duct. Blocking the ENaC inhibits uptake of lithium into the principal cells of the collecting duct within the kidney. Research has shown that amiloride can be effective in treating existing Li-NDI, but there is a lack of evidence supporting its preventative effects.1

Thiazide diuretics work by blocking the sodium-chloride cotransporter in the distal tubules of the kidney. They also upregulate the AQP2 water channels.1 Research has shown that sodium replacement counteracts the antidiuretic effect of thiazide diuretics; limitations in dietary sodium intake may be necessary for treatment efficacy.1

Within the kidneys, PGE2 inhibits adenyl cyclase and diminishes water permeability.10 This causes water to be excreted in urine rather than be reabsorbed.10 Indomethacin blocks PGE2 activity and increases water reabsorption in the collecting ducts, and sodium reabsorption in the thick ascending loop of Henle.10 This mechanism can lead to increased lithium reabsorption, which may precipitate toxicity. Research has shown increases in lithium levels by as much as 59% in addition to the risk of causing acute renal failure, especially in older adults.10 Due to these risks, indomethacin should not be considered a first-line treatment for Li-NDI.

Overall, several medications have shown benefits in the treatment of Li-NDI, with amiloride having the most data. There are currently no medications with sufficient evidence to support prophylactic use.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. V’s treatment team initiates amiloride 5 mg/d. They increase the dose to 10 mg/d after 2 days, and Ms. V’s hypernatremia resolves as her serum sodium normalizes to 142 mEq/L. Her urinary output also decreases to <3 L/d. Throughout treatment, Ms. V continues taking lithium carbonate to prevent destabilization of her BDI. The team subsequently discharges her, and she has been stable for the past 6 months.

Related Resources

- Andreasen A, Ellingrod V. Lithium-induced diabetes insipidus: prevention and management. Current Psychiatry. 2013;12(7):42-45.

- Zhang P, Gandhi H, Kassis N. Lithium-induced nephropathy; one medication with multiple side effects: a case report. BMC Nephrol. 2022;23(1):309. doi:10.1186/s12882-022-02934-0

Drug Brand Names

Amiloride • Midamor

Desmopressin • DDAVP

Hydrochlorothiazide • Microzide

Indomethacin • Indocin, Tivorbex

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

1. Schoot TS, Molmans THJ, Grootens KP, et al. Systematic review and practical guideline from the prevention and management of renal side effects of lithium therapy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:16-32.

2. Lithium induced diabetes insipidus. DiabetesInsipidus.org. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://diabetesinsipidus.org/lithium-induced-diabetes-insipidus

3. Rej S, Segal M, Low NC, et al. The McGill geriatric lithium-induced diabetes insipidus clinical study (McGLIDICS). Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(6):327-334.

4. Christensen BM, Zuber AM, Loffing J, et al. alphaENaC-mediated lithium absorption promotes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):253-261.

5. Bendz H, Aurell M, Balldin J, et al. Kidney damage in long-term lithium patients: a cross sectional study of patients with 15 years or more on lithium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(9):1250-1254.

6. Bendz H. Kidney function in a selected lithium population. A prospective, controlled, lithium-withdrawal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;72(5):451-463.

7. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28.

8. Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, et al. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):626-637.

9. Bucht G, Whalin A. Renal concentrating capacity in long-term lithium treatment and after withdrawal of lithium. Acta Med Scand. 1980;207(4):309-314.

10. Finch CK, Brooks TWA, Yam P, et al. Management and treatment of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Therapy. 2005;2(4):669-675. doi:10.1586/14750708.2.4.669

1. Schoot TS, Molmans THJ, Grootens KP, et al. Systematic review and practical guideline from the prevention and management of renal side effects of lithium therapy. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;31:16-32.

2. Lithium induced diabetes insipidus. DiabetesInsipidus.org. Accessed June 7, 2022. https://diabetesinsipidus.org/lithium-induced-diabetes-insipidus

3. Rej S, Segal M, Low NC, et al. The McGill geriatric lithium-induced diabetes insipidus clinical study (McGLIDICS). Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(6):327-334.

4. Christensen BM, Zuber AM, Loffing J, et al. alphaENaC-mediated lithium absorption promotes nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(2):253-261.

5. Bendz H, Aurell M, Balldin J, et al. Kidney damage in long-term lithium patients: a cross sectional study of patients with 15 years or more on lithium. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1994;9(9):1250-1254.

6. Bendz H. Kidney function in a selected lithium population. A prospective, controlled, lithium-withdrawal study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1985;72(5):451-463.

7. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28.

8. Garofeanu CG, Weir M, Rosas-Arellano MP, et al. Causes of reversible nephrogenic diabetes insipidus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45(4):626-637.

9. Bucht G, Whalin A. Renal concentrating capacity in long-term lithium treatment and after withdrawal of lithium. Acta Med Scand. 1980;207(4):309-314.

10. Finch CK, Brooks TWA, Yam P, et al. Management and treatment of lithium-induced nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Therapy. 2005;2(4):669-675. doi:10.1586/14750708.2.4.669

Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: Rare but serious

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

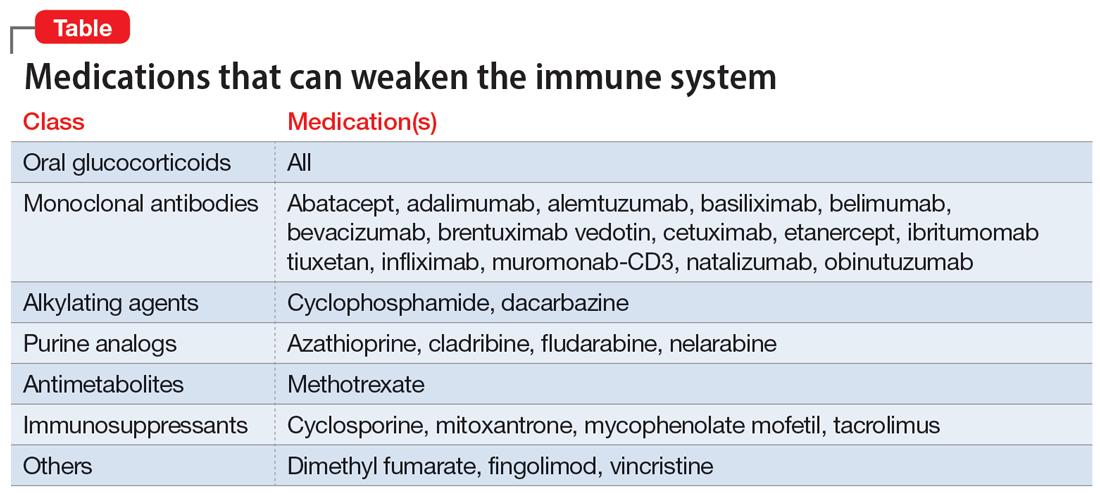

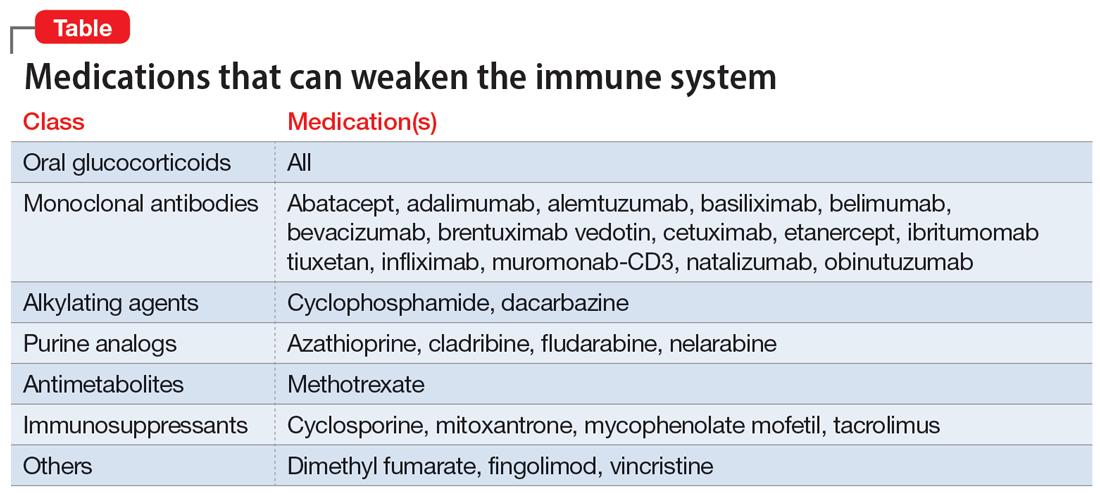

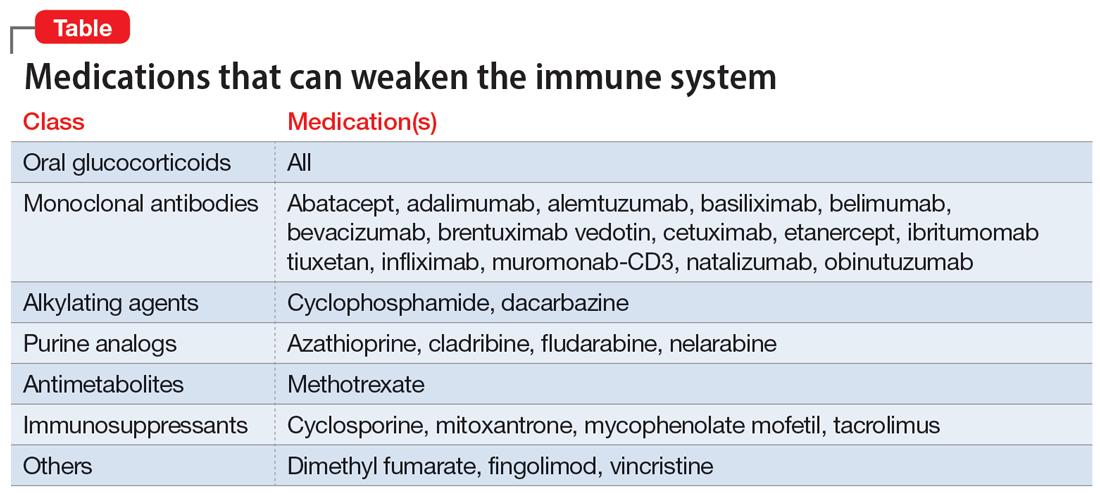

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Mr. P, age 67, presents to the clinic with vision changes and memory loss following a fall in his home due to limb weakness. Six years ago, his care team diagnosed him with rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Mr. P’s current medication regimen includes methotrexate 20 mg once weekly and etanercept 50 mg once weekly, and he has been stable on this plan for 3 years. Mr. P also was recently diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), but has not yet started treatment. Following a complete workup, an MRI of Mr. P’s brain revealed white matter demyelination. Due to these findings, he is scheduled for a brain biopsy, which confirms a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML).

PML is a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system caused by the John Cunningham virus (JCV), or JC polyomavirus, named for the first patient identified to have contracted the virus.1 Asymptomatic infection of JCV often occurs in childhood, and antibodies are found in ≤70% of healthy adults. In most individuals, JCV remains latent in the kidneys and lymphoid organs, but immunosuppression can cause it to reactivate.2

JCV infects oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and neurons, which results in white matter demyelination. Due to this demyelination, individuals can experience visual field defects, speech disturbances, ataxia, paresthesia, and cognitive impairments.2 Limb weakness presents in 60% of patients with PML, visual disturbances in 20%, and gait disturbances in 65%.3 Progression of these symptoms can lead to a more severe clinical presentation, including focal seizures in ≤10% of patients, and the mortality rate is 30% to 50%.3 Patients with comorbid HIV have a mortality rate ≤90%.2

Currently, there are no biomarkers that can identify PML in its early stages. A PML diagnosis is typically based on the patient’s clinical presentation, radiological imaging, and detection of JCV DNA. A brain biopsy is the gold standard for PML diagnosis.1

Interestingly, data suggest that glial cells harboring JCV in the brain express receptors for serotonin and dopamine.4 Researchers pinpointed 5HT2A receptors as JCV entry points into cells, and theorized that medications competing for binding, such as certain psychotropic agents, might decrease JCV entry. Cells lacking the 5HT2A receptor have shown immunity to JCV infection and the ability of cells to be infected was restored through transfection of 5HT2A receptors.4

Immunosuppressant medications can cause PML

PML was initially seen in individuals with conditions that cause immunosuppression, such as malignancies and HIV. However, “drug-induced PML” refers to cases in which drug-induced immunosuppression creates an environment that allows JCV to reactivate and disseminate back into the CNS.4 It is important to emphasize that drug-induced PML is a very rare effect of certain immunosuppressant medications. Medications that can weaken the immune system include glucocorticoids, monoclonal antibodies, alkylating agents, purine analogues, antimetabolites, and immunosuppressants (Table).1

These medications are used to treat conditions such as multiple sclerosis, RA, psoriatic arthritis, and lupus. Although drug-induced PML can result from the use of any of these agents, the highest incidence (1%) is found with natalizumab. Rates of incidence with other agents are either unknown or as low as .002%.1 Evidence suggests that the risk for PML increases with the duration of therapy.5

Continue to: Management

Management: Stop the offending agent, restore immune function

Specific pharmacologic treatments for PML are lacking. Management of drug-induced PML starts with discontinuing the offending agent. Restoring immune function has been found to be the most effective approach to treat PML.3 Restoration is possible through interleukin-2 (IL-2), IL-7, and T-cell infusions. Other treatment options are theoretical and include the development of a JCV vaccine to stimulate host response, plasma exchange to remove the medication from the host, and antiviral therapy targeting JCV replication. Diclofenac, isotretinoin, and mefloquine can inhibit JCV replication.3

Based on the theory that JCV requires 5HT2A receptors for entry into cells, researchers have studied medications that block this receptor as a treatment for PML. The first-generation antipsychotic chlorpromazine did not show benefit when combined with cidofovir, a replication inhibitor.3 Antipsychotics agents such as ziprasidone and olanzapine have shown in vitro inhibition of JCV, while risperidone has mixed results, with 1 trial failing to find a difference on JCV in fetal glial cells.3 Second-generation antipsychotics may be the preferred option due to more potent antagonism of the 5HT2A receptors and fewer adverse effects compared to agents such as chlorpromazine.4 The antidepressant mirtazapine has shown to have promising results, with evidence indicating that earlier initiation is more beneficial.3 Overall, data involving the use of medications that act on the 5HT2A receptor are mixed. Recent data suggest that JCV might enter cells independent of 5HT2A receptors; however, more research in this area is needed.2

The best strategy for treating drug-induced PML has not yet been determined. While combination therapy is thought to be more successful than monotherapy, ultimately, it depends on the patient’s immune response. If a psychotropic medication is chosen as adjunct treatment for drug-induced PML, it is prudent to assess the patient’s entire clinical picture to determine the specific indication for therapy (ie, treating symptomatology or drug-induced PML).

CASE CONTINUED

Following diagnosis, Mr. P is provided supportive therapy, and his care team discontinues methotrexate and etanercept. Although data are mixed on the efficacy of medications that work on 5HT2A receptors, because Mr. P was recently diagnosed with MDD, he is started on mirtazapine 15 mg/d at night in an attempt to manage both MDD and PML. It is possible that his depressive symptoms developed as a result of drug-induced PML rather than major depressive disorder. Discontinuing methotrexate and etanercept stabilizes Mr. P’s PML symptoms but leads to an exacerbation of his RA symptoms. Mr. P is initiated on hyd

Related Resources

- Castle D, Robertson NP. Treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Neurol. 2019;266(10):2587-2589. doi:10.1007/s00415-019-09501-y

Drug Brand Names

Abatacept • Orencia

Adalimumab • Humira

Alemtuzumab • Campath

Azathioprine • Azasan, Imuran

Basiliximab • Simulect

Belimumab • Benlysta

Bevacizumab • Avastin

Brentuximab vedotin • Adcetris

Cetuximab • Erbitux

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine, Largactil

Cidofovir • Vistide

Cladribine • Mavenclad

Cyclophosphamide • Cytoxan

Cyclosporine • Gengraf, Neoral

Dacarbazine • DTIC-Dome

Diclofenac • Cambia, Zorvolex

Dimethyl fumarate • Tecfidera

Etanercept • Enbrel

Fingolimod • Gilenya

Fludarabine • Fludara

Hydroxychloroquine • Plaquenil

Ibritumomab tiuxetan • Zevalin

Infliximab • Avsola, Inflectra

Isotretinoin • Absorica, Claravis

Mefloquine • Lariam

Methotrexate • Rheumatrex, Trexall

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Mitoxantrone • Novantrone

Muromonab-CD3 • Orthoclone OKT3

Mycophenolate mofetil • CellCept

Natalizumab • Tysabri

Nelarabine • Arranon

Obinutuzumab • Gazyva

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Risperidone • Risperdal

Tacrolimus • Prograf

Vincristine • Vincasar PFS

Ziprasidone • Geodon

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4

1. Yukitake M. Drug-induced progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in multiple sclerosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2018;9(1):37-47. doi:10.1111/cen3.12440

2. Alstadhaug KB, Myhr KM, Rinaldo CH. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen. 2017;137(23-24):10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.16.1092

3. Williamson EML, Berger JR. Diagnosis and treatment of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy associated with multiple sclerosis therapies. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(4):961-973. doi:10.1007/s13311-017-0570-7

4. Altschuler EL, Kast RE. The atypical antipsychotic agents ziprasidone, risperidone and olanzapine as treatment for and prophylaxis against progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Med Hypotheses. 2005;65(3):585-586.

5. Vinhas de Souza M, Keller-Stanislawski B, Blake K, et al. Drug-induced PML: a global agenda for a global challenge. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;91(4):747-750. doi:10.1038/clpt.2012.4