User login

Evaluation of Interventions by Clinical Pharmacy Specialists in Cardiology at a VA Ambulatory Cardiology Clinic

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

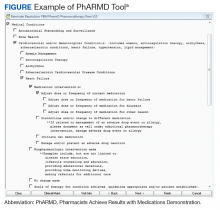

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Integration of CPSs into an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for other cardiology health care providers.

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

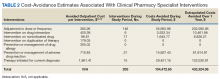

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

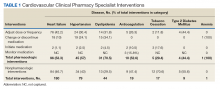

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

Health care providers face many challenges in utilizing cardiovascular therapies, such as anticipated shortages in physicians, patients with more complicated conditions, shifting medication regimens, management needs, and increased accountability for quality and performance measures.1 To meet the potential increase in service demand, cardiology practices are embracing cardiovascular team-based care.1 Advanced practice providers, such as advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs), physician assistants (PAs), and clinical pharmacy specialists (CPSs), have education, training, and experience to extend the team’s capability to meet these complex management needs.1

The role of CPSs within a cardiovascular care team includes providing a variety of patient-specific services, such as collaborating with other cardiology providers, to optimize evidence-based pharmacotherapy, preventing medication-related adverse events/errors, improving patient understanding of their medication regimen, and ultimately, improving patient outcomes.2 Health care systems, such as Kaiser Permanente of Colorado, have demonstrated improved clinical outcomes for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) by implementing a multidisciplinary collaborative cardiac care service, including a clinical pharmacy cardiac risk service, in which CPSs assisted with management of cholesterol-lowering, hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), and smoking-cessation therapies, which resulted in a 76% to 89% reduction in all-cause mortality associated with CAD in multiple evaluations.3,4

Pharmacists providing medication therapy management (MTM) services in Minnesota had higher goal attainment for patients with hypertension and hyperlipidemia than did pharmacists who did not provide MTM services.5 MTM services provided by pharmacists led to an improvement in clinical outcomes for patients as well as a reduction in overall health care expenditures compared with that of a control group of patients who did not receive MTM services.5 Furthermore, CPS integration in the heart failure (HF) setting has led to improvements in utilization and optimization of guideline-directed medical therapies, an area in which recent data have suggested deficiencies exist.6-8 A full review of the outcomes associated with CPS involvement in cardiovascular care is beyond the scope of this article; but the recent review by Dunn and colleagues provides more detail.2

With the increasing number of patients with cardiovascular disease,expanding integration of CPSs in the cardiovascular team providing MTM services may reduce the burden of other providers (MD, PA, APRN, etc), thereby increasing access for not only new patients, but also diagnostic and interventional work, while potentially improving clinical and economic outcomes.2 The value of integrating CPSs as members of the cardiovascular care team is recognized in a variety of inpatient and ambulatory practice settings.2-6 However, data are limited on the number and types of interventions made per encounter as direct patient care providers. Expanded granularity regarding the effect of CPSs as active members of the cardiovascular team is an essential component to evaluate the potential benefit of CPS integration into direct patient care.

Methods

The West Palm Beach (WPB) Veteran Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) outpatient cardiology clinic consists of 6 full-time employee (FTE) cardiologists, 4 PAs or APRNs, 10 other cardiology health care staff members (registered/license practical nurses and technicians), and 2 cardiology CPSs providing direct patient care

The cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic is open 20.5 hours per week with 41 appointment slots (30 minutes each), of which 7 appointments are delivered via clinic video telehealth and 34 appointments are traditional face-to-face visits.9 The remaining CPS time is assigned to other clinical care and administrative areas to fit facility need, including oversight of the CPS-run 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure clinic, postgraduate year 2 cardiology pharmacy practice residency program directorship, and other administrative activities for the facility.10

The cardiology CPSs practice under an advanced scope of practice in which they independently manage medications (initiate, modify, discontinue), order diagnostic testing (laboratory, monitoring, imaging, etc) needed for medication management, and create monitoring and treatment plans for patients referred to the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic by other cardiology providers. The diseases managed within the clinic vary based on patient-specific needs, but may include HF, dyslipidemia, hypertension, anticoagulation, CAD, arrhythmias, cardiovascular risk factor assessment and reduction, and medication reconciliation and teaching. Patients are referred for CPS management directly from facility cardiologist and cardiology clinic PAs and APRNs. Workload and interventions carried out are captured in the Pharmacists Achieve Results with Medications Demonstration (PhARMD) tool and patient care encounter tracking.9

Data Collection

Using local data from workload tracking, the number of CPS encounters was determined from July 6, 2015, to October 1, 2015. Data were collected on the types and volume of interventions made by CPSs in the cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic using the PhARMD tool (Figure).

The PhARMD tool was initially developed and implemented for CPSs in primary care pharmacotherapy clinics and was used to evaluate the types and volume of CPS interventions made in this setting.11 Since this initial evaluation, the tool has been updated, standardized nationally by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Pharmacy Benefits Management Clinical Pharmacy Practice Office, and integrated across numerous VAMCs and associated outpatient clinics. The tool remains embedded within the VA electronic health record (EHR) and allows the capture of specific CPS interventions of several types (ie, both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions, including adjust dose or frequency; change or discontinue medication; initiate medication; monitor medication; counsel on adherence, contraindications, drug interactions, and drugs not indicated; reconcile medication; and prevent or manage adverse drug events [ADEs]) specific to certain diseases, such as anemia, anticoagulation, HF, type 2 DM (T2DM), hypertension, dyslipidemia, and tobacco cessation.

Given that the interventions captured by the PhARMD tool are based on self-report of the CPS performing the intervention, a quality assurance (QA) measure was taken to audit a random sample of interventions to validate the accuracy of reported data. A Pharmacy Benefits Management PhARMD Project QA report provided the 20% random sample of encounters for each cardiology CPS to be reviewed. This percentage was determined by VAMC Clinical Pharmacy Program Office (CPPO) directives on implementation of the PhARMD tool. During the QA period, the provided sample was reviewed to determine whether the intervention(s) recorded with the PhARMD tool matched the actions documented in the EHR. The QA review was done through a manual chart review by an author not involved in recording the original interventions. Both WPB VAMC cardiology CPSs passed the QA review (> 80% concurrence with tool logged and chart documented interventions as required by VA CPPO directive), with a 90.9% concurrence between the EHR and PhARMD tool documentation.

Statistical Analyses

Data on intervention type and encounter number were evaluated with descriptive statistics. The information was characterized and diagrammed with Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) charts and graphs.

Cost-avoidance calculations were done using previously described methods and are included for exploratory analysis.11,12 Briefly, published estimates of cost avoidance associated with various interventions from the outpatient setting within a VAMC setting were applied as appropriate to the various interventions captured with the PhARMD tool.11,12 These estimates from Lee and colleagues were derived from detailed chart review of interventions made and the potential harm prevented.12 Costs or cost avoidances associated with interventions were calculated from pooled examination of 600 interventions in a VAMC with drug costs before and after the intervention, costs associated with harms prevented by the intervention, as well as the VAMC hourly pharmacist wages associated with making an intervention and processing and filling original vs recommended therapies.

The costs presented represent a “best-case” scenario in which all interventions made are expected to prevent patient harms. The costs related to avoided outcomes, facility overhead, and auxiliary staff cannot be included but highlight the many considerations that must be considered when examining potential cost-avoidance calculations. The estimates and methods at hand were chosen because, to our knowledge, no other consensus model exists that would be more appropriate for use in the situation and health care system at hand. Cost-avoidance estimates were calculated by extrapolating the 88-day study period values to a yearly estimate. All cost estimates were adjusted for inflation using the consumer price index calculator as per convention in previous analyses using the cost-avoidance estimates at hand.11-13

Results

From July 6, 2015, through October 1, 2015, 301 patient encounters occurred, and 529 interventions were documented with the PhARMD tool. The mean number of interventions per encounter was 1.8. Interventions were 65.2% pharmacologic and 34.8% nonpharmacologic. Of pharmacologic interventions, 27.1% were for HF, 12.7% for hypertension, 8.8% for dyslipidemia, 2.8% for anticoagulation, 1.4% for tobacco cessation, 1.1% for T2DM, 0.3% for anemia, and 45.8% for other conditions (Table 1).

The main types of pharmacologic interventions across all diseases were related to adjustments in medication dose or frequency (42.3%) and change or discontinuation of medications (20.0%).

Discussion

Evaluation of the interventions and encounters at the WPB VAMC ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic suggests that CPSs are able to contribute to direct patient care independently of interventions performed by other cardiology providers. Specifically, 1.8 interventions per encounter were made by CPSs in this study. In a prior evaluation of CPS interventions recorded with the PhARMD tool in a VAMC primary care setting, 2.3 interventions per encounter were recorded.11 In comparing the present volume of interventions with the volume recorded in the study by Hough and colleagues, the difference in practice setting may account for differences seen.11

The primary care medication management setting would capture a broader array of clinical interventions than would the ambulatory cardiology clinic of the present study, so it is reasonable that more interventions would be captured per encounter in the primary care clinic. The difference in practice settings affecting the character of collected interventions can be seen because most interventions in this study at an ambulatory cardiology clinic were related to HF, whereas in Hough and colleagues 39.2% of the disease-specific interventions were related to DM, and only 2.9% were related to HF.11 The differences inherent in the intervention populations can also be seen by comparing the percentage of interventions related to hypertension and dyslipidemia: 30% and 28% in the study by Hough and colleagues compared with 13% and 9%, respectively, in the present study.11

Comparison of the present evaluation and Hough and colleagues is also hindered by the PhARMD tool used. The PhARMD tool used in the initial evaluation has been modified on a national level to improve the granularity of intervention data collected.

Our cost-avoidance estimate of $433,324.06 per year seems lower than that estimated in the previous evaluation when all applicable interventions were included.11 However, this study had several differences compared with those of previous VAMC studies looking at clinical interventions performed by CPSs. The main differences are the volume and setting in which interventions were being made. For example, in comparison with Hough and colleagues, the studies include different practice settings (primary care vs cardiology specialty clinic) and number of FTEs involved in the study (4.65 vs 1). If the cost avoidance is distributed evenly per FTE in the previous study, the following calculation is observed: $649,551.99 per FTE, which is closer to this study’s estimation. Given that primary care is a broader setting than is ambulatory cardiology, it is not surprising that more types of interventions and the overall volume/absolute number of interventions would be higher. Thus, the lower estimated cost avoidance in our study may be attributed to the lower volume of intervention opportunities availed to the cardiology CPS. Another difference is that detailed types of interventions related to hypertension, DM, dyslipidemia, and HF were not included in Hough and colleagues, whereas our study included all applicable interventions regardless of relation to diseases, which may account for a degree of the variation in intervention breakdown between the 2 studies.11 However, as noted previously, some interventions for these particular diseases may not fully capture the rationale for pharmacotherapy interventions, such as drug dose changes or discontinuations, which may misrepresent the potential cost avoidance associated with them in reality.

Limitations

Of general importance, the PhARMD tool may underestimate the number of interventions made such that multiple interventions for a medical condition may have been completed but only captured as 1 intervention, which may represent a limitation of the tool when multiple interventions are made for the same disease (eg, titration of both β-blocker and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor doses at a single appointment in a patient with HF with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction). Improved clarity about interventions made would require laborious chart review, which was not feasible. The evaluation at hand included a preliminary QA review, adding confidence that overdocumentation was not being done and the values represented at worst an underestimation of actual CPS intervention impact. Because this study was an initial evaluation of interventions made by CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology pharmacotherapy setting, whether these same outcomes would exist in other patient cohorts is unclear. However, these data do provide a foundational understanding of what may be expected from CPS integration into a cardiovascular care team.

These findings may be limited in generalizability to other health care systems and situations in which CPSs are afforded the regulatory opportunity to practice independently within an established scope of practice or collaborative practice agreements. The Veterans Health Administration system has been a leader in integrating CPSs into direct patient care roles and serves as a potential model for application by other groups. This evaluation’s data support continued efforts to create such independent practice environments as they allow for qualified CPSs to practice to their full clinical potential and have the fullest possible effect on cardiovascular outcomes.

Previous studies looking at cost savings in MTM programs have established a substantial return in economic investment with patients being managed by pharmacists.5,14 Given that the interventions made in this study were not tied to attainment of clinical outcomes, a limitation to our study, the cost-avoidance estimates should be interpreted cautiously. However, we know of no such tool that is available to allow accurate capture of clinical event reduction in a single center with consistent CPS involvement in care. A clear opportunity exists regarding design of a model that measures clinical, economic, and humanistic outcomes related to the interventions performed by cardiology CPSs, but developing and deploying such a model may be challenging because guideline-directed medical therapies vary significantly based on many patient-specific issues, and identifying optimal or truly optimized medical therapy is at times a subjective task, especially in a single center. Using the types and volumes of interventions made by CPSs as a surrogate for these higher-level outcomes is still of value in order to understand the effect and role of CPSs in cardiovascular care. At present, the cost-avoidance estimates presented in this evaluation are based on the most appropriate system-specific data at hand, with the realization that actual cost avoidance in practice may vary widely and should be the topic of future research.

Conclusion

As cardiovascular team-based care continues to expand with the support of large organizations, such as the American College of Cardiology Foundation, Heart Failure Society of America, and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network, the need for understanding the effect of CPSs on patient care measures and health care costs becomes more pronounced.2,15 The results of this study demonstrate how integration of CPSs in an ambulatory cardiology clinic may translate to cost avoidance and a reduction in workload burden for cardiology physicians and providers, allowing more availability for diagnostic testing and care.

Interventions made by CPSs functioning as independent providers

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

1. Brush JE Jr, Handberg EM, Biga C, et al. 2015 ACC health policy statement on cardiovascular team-based care and the role of advanced practice providers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(19):2118-2136.

2. Dunn SP, Birtcher KK, Beavers CJ, et al. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the care of patients with cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(19):2129-2139.

3. Sandoff BG, Kuca S, Rasmussen J, Merenich JA. Collaborative cardiac care service: a multidisciplinary approach to caring for patients with coronary artery disease. Perm J. 2008;12(3):4-11.

4. Merenich JA, Olson KL, Delate T, Rasmussen J, Helling DK, Ward DG; Clinical Pharmacy Cardiac Risk Service Study Group. Mortality reduction benefits of a comprehensive cardiac care program for patients with occlusive coronary disease. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(10):1370-1378.

5. Isetts BJ, Schondelmeyer SW, Artz MB, et al. Clinical and economic outcomes of medication therapy management services: the Minnesota experience.

6. Martinez AS, Saef J, Paszcuzuk A, Bhatt-Chugani H. Implementation of a pharmacist-managed heart failure medication titration clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(12):1070-1076.

7. Roth GA, Poole JE, Zaha R, Zhou W, Skinner J, Morden NE. Use of guideline-directed medications for heart failure before cardioverter-defibrillator implantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(9):1062-1069.

8. Noschese LA, Bergman CL, Brar CK, Kansal MM. The pharmacist’s role in medication optimization for patients with chronic heart failure. Fed Pract. 2017;34(suppl 10):S10-S15.

9. Coakley C, Hough A, Dwyer D, Parra D. Clinical video telehealth in a cardiology pharmacotherapy clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(22):1974-1975.

10. Khazan E, Anastasia E, Hough A, Parra D. Pharmacist-managed ambulatory blood pressure monitoring service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(4):190-195.

11. Hough A, Vartan CM, Groppi JA, Reyes S, Beckey NP. Evaluation of clinical pharmacy interventions in a Veterans Affairs medical center primary care clinic. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(13):1168-1172.

12. Lee AJ, Boro MS, Knapp KK, Meier JL, Korman NE. Clinical and economic outcomes of pharmacist recommendations in a Veterans Affairs medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2002;59(21):2070-2077.

13. US Department of Labor. CPI inflation calculator. www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm. Accessed January 18, 2019.

14. Perez A, Doloresco F, Hoffman JM, et al. Economic evaluations of clinical pharmacy services: 2001-2005. Pharmacotherapy. 2008;29(1):128.

15. Milfred-LaForest SK, Chow SL, DiDomenico RJ, et al. Clinical pharmacy services in heart failure: an opinion paper from the Heart Failure Society of America and American College of Clinical Pharmacy Cardiology Practice and Research Network. Pharmacotherapy. 2013;33(5):529-548.

Roundtable Discussion: Anticoagulation Management

Case 1

Tracy Minichiello, MD. The first case we’ll discuss is a 75-year-old man with mild chronic kidney disease (CKD). His calculated creatinine clearance (CrCl) is about 52 mL/min, and he has a remote history of a gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding 3 years previously from a peptic ulcer. He presents with new onset nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF), and he’s already on aspirin for his stable coronary artery disease (CAD).

How do we think about anticoagulant selection in this patient? We have a number of new oral anticoagulants and we have warfarin. How do we decide between warfarin vs one of the direct-acting oral anticoagulants (DOACs)? If we choose a DOAC, which one would we select?

David Parra, PharmD. The first step for anticoagulation is to assess a patient’s thromboembolic risk utilizing the CHA2DS2-VASc and bleeding risk using a HAS-BLED score, or something similar. The next question is which oral anticoagulant to use. We have widespread experience with warfarin and can measure the anticoagulant effect easily. Warfarin has a long duration of action, so perhaps it’s more forgiving if you miss a dose. It also has an antidote. Lastly, organ dysfunction doesn’t preclude use of warfarin as you can still monitor the anticoagulant effect. So there still may be patients that may benefit significantly from warfarin vs a DOAC.

On the flip side, DOACs are easier to use and perform quite acceptably in comparison with warfarin in nonvalvular AF. There are some scenarios where a specific DOAC may be preferred over another, such as recent GI bleeding.

Dr. Minichiello. Do you consider renal function, bleeding history, or concomitant antiplatelet therapy?

Geoffrey Barnes, MD, MSc. A couple of factors are relevant. I think we should consider renal function for this gentleman. However, I look at some of the other features as Dr. Parra suggested. What’s the likelihood that this patient is going to take the medicine as prescribed? Is a twice-a-day regimen going to be something that’s particularly challenging? I also look at the real-world vs randomized trial experience.

This patient has a remote GI bleeding history. Some of the real-world data suggest there might be some more GI bleeding with rivaroxaban, but across the board, apixaban (in both the randomized trials and much of the real-world data) seem to have a favorable bleeding risk profile. For a patient who is open and reliable for taking medicine twice a day, apixaban might be a good option as long as we make sure that the dose is appropriate.

Arthur L. Allen, PharmD, CACP. In pivotal trial experience, dabigatran and rivaroxaban demonstrated an increased incidence of GI bleeding compared with warfarin. In some of the real-world studies, rivaroxaban mirrors warfarin with regard to bleeding, whereas dabigatran and apixaban have a lower incidence. In the pivotal trials, apixaban did not have a trigger of increased GI bleeding, but I would let the details of this patient’s GI bleeding history help me determine how important an issue this is at this point.

The other thing that is important to understand when considering choice of agents: As Dr. Parra mentioned, we do have quite a bit of experience with warfarin. But comparing the quality of evidence, the DOACs have been investigated in a far more rigorous fashion and in far more patients than warfarin ever was in its more than 60 years on the market. For example, the RE-LY trial alone enrolled more than 18,000 patients. Each of the DOACs have been studied in tens of thousands of patients for their approved indications. Further, we shouldn’t forget that the risk of intracranial hemorrhage is reduced by roughly 50% by choosing a DOAC over warfarin, which should be a consideration in this elderly gentleman.

Dr. Minichiello. In the veteran population, there is a sense of comfort with warfarin, and some concerns have been raised over a lack of reversibility for the newer agents. We have patients who have trepidation about starting one of the new anticoagulants. However, there is a marked reduction in the risk of the most devastating bleeding complication, namely intracranial hemorrhage, making the use of these agents most compelling. And when they did have bleeding complications, at least in the trials, their outcomes were no worse than they were with warfarin, where there is a reversal agent. In most cases the outcomes were actually better.

Dr. Barnes. You often have to remind patients that there was no reversal agent in these huge trials where the DOACs showed similar or safer bleeding risk profiles, especially for the most serious bleeding, such as intracranial hemorrhage. I find patients often are reassured by knowing that.

Dr. Allen. I agree that there is concern about the lack of reversibility, but I think it has been completely overplayed. In the pivotal trials, patients who bled on DOAC therapy actually had better outcomes than those that bled on warfarin. This includes intracranial hemorrhage. There was a paper published in Stroke in 2012 that evaluated the subgroup of patients in the RE-LY trial that suffered intracranial hemorrhage. Patients on dabigatran actually fared better despite a lack of a specific reversal agent. When evaluating the available data about reversal of the DOACs, I’m not 100% convinced that we’re significantly impacting outcomes by reversing these agents. We’re certainly running up the bill, but are we treating the patient or treating the providers? As long as the renal function remains intact, the DOACs clear quickly, perhaps more quickly than warfarin can typically be reversed with standard reversal agents.

Dr. Minichiello. Remember that this patient has a history of a GI bleed. We are going to start him on full-dose anticoagulation for stroke prevention for his nonvalvular AF. He’s also on aspirin, and he has stable coronary disease. He does not have any stents in place but he did have a remote non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) a number of years ago. Do we feel that the risk of dual therapy—anticoagulation combined with antiplatelet therapy—outweighs the risks? And how do we approach that risk?

Dr. Barnes. This is an important point to discuss. There has been a lot of discussion in the literature recently. When I start this type of patient on an oral anticoagulant, I try to discontinue the antiplatelet agent because I know how much bleeding risk that brings. The European guidelines (for example, Eur Heart J. 2014;35[45]:3155-3179) have been forward thinking with this for the last couple of years and have highlighted that if there’s an indication for anticoagulation for patients with stable coronary disease, meaning no MI and no stent within the past year, then we should stop the antiplatelet agents after a year in order to reduce the risk of MI. This is based on a lot of older literature where warfarin was compared with aspirin and shown to be protective in coronary patients, but at the risk of bleeding.

It’s important because there have been recent studies that have raised questions, including a recent Swedish article in (Circulation. 2017;136:1183-1192) that suggested discontinuing aspirin led to increased mortality. But it’s important to look at the details. While that was true for most patients, it was not true for the group of patients who were on an oral anticoagulant. Many colleagues ask me questions about that particular paper and its media coverage. I tell them that for our patients on chronic oral anticoagulants, the paper supports the notion that there is not increased mortality when aspirin use is stopped. We know that aspirin plus an anticoagulant leads to increased bleeding, so I try to stop it for patients who have stable CAD but are on long-term anticoagulation.

Dr. Allen. This isn’t a new thought. Back in early 2012, the 9th edition of the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) Antithrombotic Guidelines probably gave us the best guidance that we had ever seen to help us address this issue. Since that time the cardiology guidelines have caught up to recommend that we do not need additional antiplatelet therapy for stable CAD, and, in fact, it should be limited even in the setting of acute coronary syndromes and percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

Dr. Minichiello. That’s a good point because people are not necessarily clear about when there would be an indication to continue dual therapy and when it is safe to go to monotherapy. Scenarios where benefit of dual therapy may outweigh risk suggested in the CHEST 2012 guidelines include acute coronary syndrome or a recent stent, high-risk mechanical valves, and history of coronary artery bypass surgery.

I think the important thing is to consider each case individually and not to reflexively continue aspirin therapy. Often what we see is once on aspirin—always on aspirin. Being thoughtful about it, we should acknowledge that it likely results in a 2-fold increased risk of bleeding and make sure that we believe that the benefit outweighs the risk.

Dr. Allen. I agree. We probably have better evidence in the CAD population, but what do we do for patients with significant peripheral vascular disease, or those patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis or history of strokes? Some of the European guidance suggests taking a similar approach to CAD, but these are the patients for whom stopping aspirin makes me more nervous.

Dr. Parra. This is a perfect example of where less is more. All too often the reflex is to continue aspirin treatment indefinitely because the patient has a history of acute coronary syndrome or even peripheral arterial disease, when the best thing to do would be to drop the aspirin. It involves an individualized risk assessment and underscores the need to periodically do a risk/benefit assessment in all patients on anticoagulants, whether it’s warfarin or a DOAC.

I’d like to take a moment and step back to the case in the context of the GI bleeding. When we look at patients with a history of GI bleeding, it is important to understand the circumstances that surround it. This individual had a GI bleed 3 years previously and peptic ulcer disease. In these situations I ask whether the patient was taking over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflamitory drugs at the time, had excessive alcohol use, or was successfully treated for Helicobacter pylori. All of these may influence whether or not I think the GI bleed is significant to influence the DOAC choice.

The other thing I consider is that the overall risk of major GI bleeding in those pivotal DOAC trials was quite small, < 1.5% per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily and < 1% per year with apixaban. The numbers needed to harm were quite high, over 200 patients per year with dabigatran 150 mg twice daily vs warfarin and over 350 patients per year with edoxaban 60 mg daily vs warfarin. There are no head-to-head comparisons with DOACs, but this small increased risk vs warfarin may still be an important consideration in some patients. In addition, it is important to remember that intracranial hemorrhage and fatal bleeding was less in all the pivotal NVAF trials with the DOACs when compared with warfarin. So that is something we need to reinforce with patients when we discuss treatment regardless of the DOAC selected.

Case 2

Dr. Minichiello. The next case is a 63-year-old man with hypertension, diabetes mellitus, nonvalvular AF, and he is taking dabigatran for stroke prevention. He presents in the emergency department with chest pain, and he is found to have a non-ST elevation MI. He goes to the cath lab and he is found to have a lesion in his left circumflex. The patient receives a newer generation drug-eluting stent. What are we going to do with his anticoagulation? We know he’s going to get some antiplatelet therapy, but what are our thoughts on this?

Dr. Parra. This is something that we run into all too often. I think the estimates are about 20% to 30% of patients who have indications for anticoagulation also end up having ischemic heart disease that requires PCI. The second thing is that we know combining an anticoagulant with antiplatelet therapy is associated with a 4% to 16% risk of fatal and nonfatal bleeding, and we have found out in patients with ischemic heart disease that when they bleed, they also have a higher mortality rate.

We’re trying to find the optimal balance between ischemic and thrombotic risk and bleeding risk. This is where some of the risk assessment tools that we have come into play. First, we need to establish the thrombotic risk by considering the CHA2DS2-VASc score, and the factors associated with increasing bleeding risk and stent thrombosis. You have time to work this out because, initially, all patients that are at sufficiently high thrombotic risk will receive dual antiplatelet therapy and anticoagulation therapy for a given period. This gives providers time to use some of those resources and figure out a long-term plan for the patient.

Dr. Allen. The fear and loathing that this brings up comes back to some historic things that should be considered. What we did for drug-eluting stents or bare-metal stents comes from older data where different stent technology was used. The stents used today are safer with a lower risk of in-stent thrombosis. Historically, we knew what to do for ACS and PCI and we knew what to do for AF, but we didn’t know what to do when the 2 crossed paths. We would put patients on warfarin and say, “Well, for now, target the INR between 2 and 2.5 and good luck with that.” That was all we had. The good news is now we have some evidence to move away from the use of dual antiplatelet plus anticoagulant therapies.

There were 2 DOAC studies recently published: The PIONEER-AF trial used rivaroxaban and more recently the RE-DUAL PCI trial used dabigatran. Each of the studies had some issues, but they were both studied in AF populations and aimed to address this issue of triple therapy. The PIONEER-AF trial looked at a number of different scenarios on different doses of rivaroxaban with either single or dual antiplatelet therapy compared to triple therapy with warfarin. The RE-DUAL PCI trial with dabigatran was less complex. Both studies were powered to look at safety, and they did show that with single antiplatelet plus oral anticoagulation regimens, the incidence of major bleeding complications was reduced.

However, that brings up some issues about how the studies were conducted. Both studied AF populations and in some cases did not study doses approved for AF. Yet at the same time, the studies were not powered to look at stroke outcomes, which raises the question: Are we running the risk of giving up stroke efficacy for reduced bleeding? I don’t think that we’ve fully answered that, certainly not with the PIONEER AF trial.

Dr. Parra. I agree. When we look at those trials, 2 things come to mind. First, the doses of dabigatran used in the RE-DUAL PCI trial were doses that have been shown to be beneficial in the nonvalvular AF population. Second, a take-home point from those trials is the P2Y12 inhibitor that was utilized—close to 90% or more used clopidogrel in the PIONEER-AF trial. Clopidogrel remains the P2Y12 inhibitor of choice. One of the other findings is that the aspirin dosing should be low, < 100 mg daily, and that we need to consider routine use of proton pump inhibitors to protect against the bleeding that can be found with the antiplatelet agents.

Also of interest, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) recently released a focused update with some excellent recommendations on dual antiplatelet therapy in coronary artery disease in which they incorporated the results from the PIONEER-AF-PCI trial. The RE-DUAL PCI trial had not been published when these came out. If you’re concerned about ischemic risk prevailing, ESC recommendations based upon risk stratification are triple therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, and an oral anticoagulant for longer than 1 month and up to 6 months and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months; afterward just oral anticoagulation alone. If the concerns about bleeding prevail, then we have 2 different pathways: one limiting triple therapy to 1 month and then dual therapy with 1 antiplatelet agent and an oral anticoagulant to complete the 12 months. But the ESC also has a second recommendation for patients at high risk of bleeding, which is dual therapy with clopidogrel and an oral anticoagulant at the offset for up to 12 months. I found these guidelines to be particularly helpful in terms of how to put this into practice.

Dr. Allen. There’s still so much concern about in-stent thrombosis. Although a smaller trial, we knew from the WOEST trial that single antiplatelet therapy with warfarin was reasonable. We know from the PIONEER-AF and RE-DUAL PCI trials that we didn’t get significantly more in-stent thrombosis by giving up the second antiplatelet. Whether or not we answered the stroke question is another issue, but the cardiology societies are still hanging on to dual antiplatelet therapy. I question if that’s based on the older data and the older stent technologies.