User login

Pruritic Eruption With Skinfold Sparing

The Diagnosis: Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji

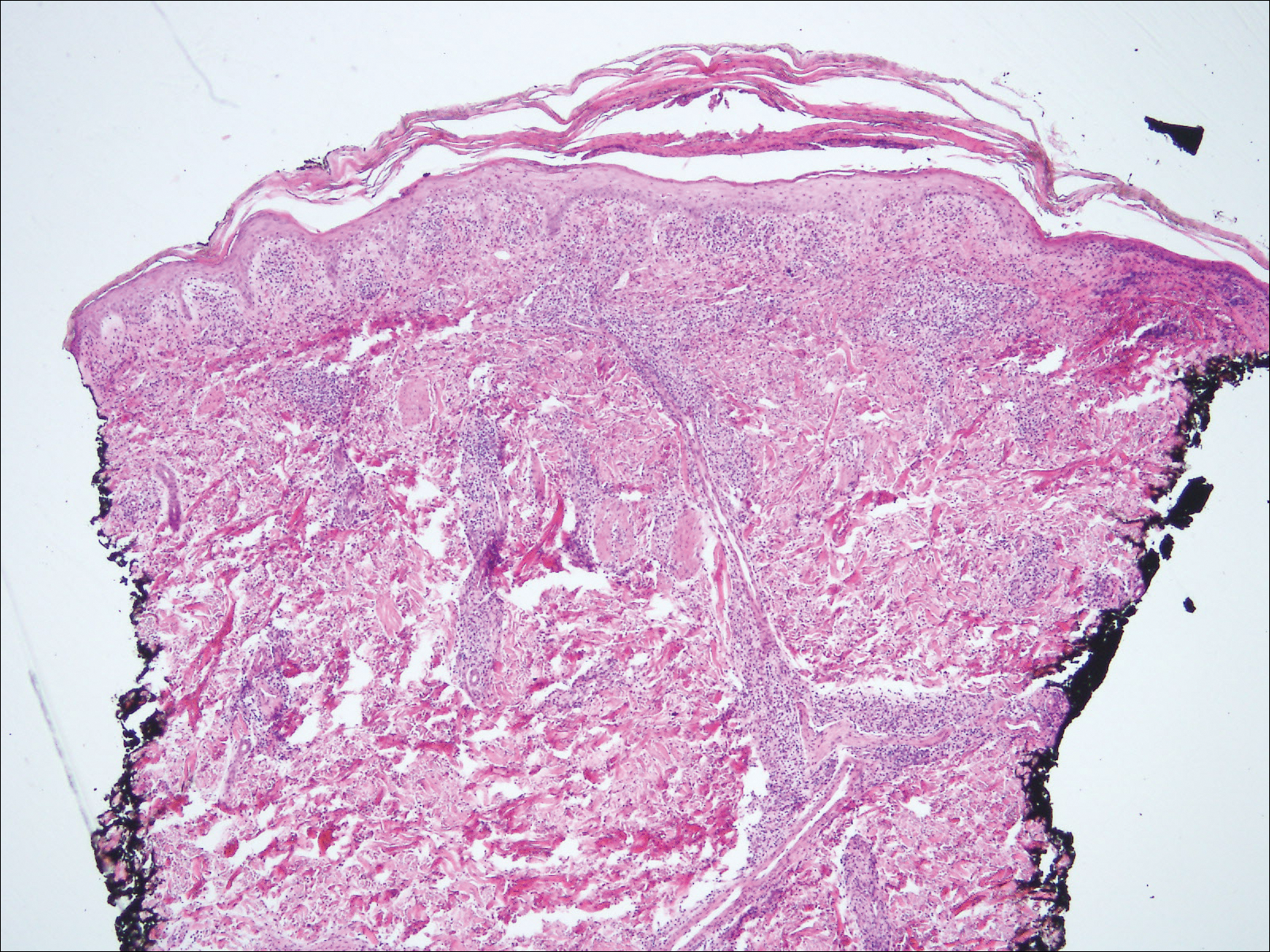

The patient presented with a characteristic finding of skinfold sparing, known as the "deck-chair sign" (Figure 1).1 A repeat biopsy at our institution revealed a dermal perivascular and bandlike infiltrate with lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). The epidermis showed mild spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, and rare necrotic keratinocytes. A T-cell gene rearrangement assay was negative for a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes. Based on the clinical and histologic features, the diagnosis was most consistent with papuloerythroderma of Ofuji (PEO); however, a lymphoproliferative disorder needed to be excluded. Further workup included a peripheral smear, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, IgE level, and hepatitis panel; all were normal, except for an elevated serum IgE level. Human immunodeficiency virus and age-appropriate malignancy screening were negative. The patient was prescribed betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which resulted in near-complete resolution of the rash and marked improvement in pruritus.

In 1984, PEO was described as an entity of generalized pruritic erythroderma characterized by flat-topped, red to brown, coalescing papules with sparing of the skinfolds, later coined the deck-chair sign.1,2 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji commonly presents in elderly Asian males with a male to female ratio of 4:1.3 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji is a T cell-mediated skin disease; however, the etiology of the signature rash remains unclear. One explanation includes circulating factors in the skin that elicit an inflammatory response, which does not occur in areas of external pressure.3 The deck-chair sign may occur more frequently in elderly individuals due to increased skin laxity, which creates crease lines that are spared from rubbing and excoriations.4

Although Ofuji et al2 initially reported 4 idiopathic cases, subsequent authors described PEO in association with other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and atopic diathesis, and infections, as well as secondary to medications. Some authors have suggested that PEO may be an early variant of mycosis fungoides; therefore, physicians should monitor patients closely.5-7 Maher et al6 commented that multiple causative factors including CTCL underlie the development of papuloerythroderma.

In a review of PEO, Torchia et al3 proposed diagnostic criteria and an etiologic classification to address whether PEO represents an independent entity or an unusual manifestation of other dermatoses. They established 4 categories of papuloerythroderma--primary, secondary, papuloerythrodermalike CTCL, and pseudopapuloerythroderma--and proposed that primary PEO is a diagnosis of exclusion. If no secondary association is found, they proposed 10 criteria for primary PEO: 5 major criteria include coalescing flat-topped papules, the deck-chair sign, pruritus, histopathologic exclusion of diseases such as CTCL, and a negative workup to exclude other causes.3 In 2018, Maher et al6 recommended workup to rule out cutaneous malignancy, including skin biopsy, flow cytometry, Sézary cell count, T-cell rearrangement, lactate dehydrogenase, and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. The 5 minor criteria proposed by Torchia et al3 include age older than 55 years, male sex, eosinophilia, elevated IgE level, and lymphopenia. Our patient fulfilled all 5 major criteria and 3 minor criteria; eosinophilia and lymphopenia were absent.

Clinically, PEO has been associated with the deck-chair sign, a pattern of selective sparing of skinfolds, including axillary, inguinal, submammary, and other flexural areas. Although the deck-chair sign was originally considered pathognomonic for PEO, this clinical pattern also has been observed in other entities, such as angioimmunoblastic lymphoma, cutaneous Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and acanthosis nigricans.5,8,9

Specific characteristics of the rash and certain clinical symptoms may help to distinguish the deck-chair sign of PEO from its other causes. Although malignant acanthosis nigricans may spare the skinfolds, lesions have a classic velvety thickening and brownish hyperpigmentation, which is not characteristic of the reddish brown, flat-topped papules of PEO.9 Pai et al5 described a patient with parthenium dermatitis presenting with the deck-chair sign that developed years after repeated exposure to the allergen. Our patient did not have a history of repeated episodes of allergic contact dermatitis. In addition, areas of sparing may mimic the appearance of pityriasis rubra pilaris. As in our patient, those with PEO generally lack the follicular hyperkeratotic papules, palmoplantar keratoderma, widespread orange-red erythema, and characteristic histopathologic finding of hyperkeratosis with alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, allowing these entities to be easily distinguished in most instances.10

Histopathologically, primary PEO shows a nonspecific spongiotic dermatitis-like pattern characterized by slight epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and a predominantly perivascular dermal infiltrate with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils.3 These histologic findings may at times show some overlap with CTCL, and therefore T-cell gene rearrangement and flow cytometry may be performed in those instances.6

Treatment includes the management of any underlying condition causing the papuloerythroderma.3,6 There are no large clinical trials of treatment options for primary PEO due to its rarity. Topical or systemic corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment.3 Alternative treatments used with variable success include phototherapy, interferon, etretinate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine.11 Allegue et al11 successfully used methotrexate to treat a patient with primary PEO and postulated that methotrexate may act through an immunosuppressive mechanism on activated T cells due to the involvement of helper T cells TH2 and TH22 in its pathogenesis.

Although the cutaneous manifestations of PEO may respond well to topical steroids, it is important to consider the possible presence of an underlying malignancy and other associated systemic conditions.

- Farthing CF, Staughton RC, Harper JI, et al. Papuloerythroderma--a further case with the 'deck chair sign.' Dermatologica. 1986;172:65-66.

- Ofuji S, Furukawa F, Miyachi Y, et al. Papuloerythroderma. Dermatologica. 1984;169:125-130.

- Torchia D, Miteva M, Hu S, et al. Papuloerythroderma 2009: two new cases and systematic review of the worldwide literature 25 years after its identification by Ofuji et al. Dermatology. 2010;220:311-320.

- Ochi H, Ang CC. Novel association of a papuloerythroderma of Ofuji phenotype with dermatitis herpetiformis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:856-857.

- Pai S, Shetty S, Rao R. Parthenium dermatitis with deck-chair sign. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:906-907.

- Maher AM, Ward CE, Glassman S, et al. The importance of excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in patients with a working diagnosis of papuloerythroderma of Ofuji: a case series. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:46-54.

- Grob JJ, Collet-Villette AM, Horchowski N, et al. Ofuji papuloerythroderma. report of a case with T cell skin lymphoma and discussion of the nature of this disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(5 pt 2):927-931.

- Ferran M, Gallardo F, Baena V, et al. The 'deck chair sign' in specific cutaneous involvement by angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Dermatology. 2006;213:50-52.

- Murao K, Sadamoto Y, Kubo Y, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans with "deck-chair sign." Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:377-378.

- Regina G, Paramita L, Radiono S, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji in Indonesia: the first case report. JDVI. 2016;1:93-98.

- Allegue F, Fachal C, Gonzalez-Vilas D, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji successfully treated with methotrexate. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12638.

The Diagnosis: Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji

The patient presented with a characteristic finding of skinfold sparing, known as the "deck-chair sign" (Figure 1).1 A repeat biopsy at our institution revealed a dermal perivascular and bandlike infiltrate with lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). The epidermis showed mild spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, and rare necrotic keratinocytes. A T-cell gene rearrangement assay was negative for a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes. Based on the clinical and histologic features, the diagnosis was most consistent with papuloerythroderma of Ofuji (PEO); however, a lymphoproliferative disorder needed to be excluded. Further workup included a peripheral smear, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, IgE level, and hepatitis panel; all were normal, except for an elevated serum IgE level. Human immunodeficiency virus and age-appropriate malignancy screening were negative. The patient was prescribed betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which resulted in near-complete resolution of the rash and marked improvement in pruritus.

In 1984, PEO was described as an entity of generalized pruritic erythroderma characterized by flat-topped, red to brown, coalescing papules with sparing of the skinfolds, later coined the deck-chair sign.1,2 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji commonly presents in elderly Asian males with a male to female ratio of 4:1.3 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji is a T cell-mediated skin disease; however, the etiology of the signature rash remains unclear. One explanation includes circulating factors in the skin that elicit an inflammatory response, which does not occur in areas of external pressure.3 The deck-chair sign may occur more frequently in elderly individuals due to increased skin laxity, which creates crease lines that are spared from rubbing and excoriations.4

Although Ofuji et al2 initially reported 4 idiopathic cases, subsequent authors described PEO in association with other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and atopic diathesis, and infections, as well as secondary to medications. Some authors have suggested that PEO may be an early variant of mycosis fungoides; therefore, physicians should monitor patients closely.5-7 Maher et al6 commented that multiple causative factors including CTCL underlie the development of papuloerythroderma.

In a review of PEO, Torchia et al3 proposed diagnostic criteria and an etiologic classification to address whether PEO represents an independent entity or an unusual manifestation of other dermatoses. They established 4 categories of papuloerythroderma--primary, secondary, papuloerythrodermalike CTCL, and pseudopapuloerythroderma--and proposed that primary PEO is a diagnosis of exclusion. If no secondary association is found, they proposed 10 criteria for primary PEO: 5 major criteria include coalescing flat-topped papules, the deck-chair sign, pruritus, histopathologic exclusion of diseases such as CTCL, and a negative workup to exclude other causes.3 In 2018, Maher et al6 recommended workup to rule out cutaneous malignancy, including skin biopsy, flow cytometry, Sézary cell count, T-cell rearrangement, lactate dehydrogenase, and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. The 5 minor criteria proposed by Torchia et al3 include age older than 55 years, male sex, eosinophilia, elevated IgE level, and lymphopenia. Our patient fulfilled all 5 major criteria and 3 minor criteria; eosinophilia and lymphopenia were absent.

Clinically, PEO has been associated with the deck-chair sign, a pattern of selective sparing of skinfolds, including axillary, inguinal, submammary, and other flexural areas. Although the deck-chair sign was originally considered pathognomonic for PEO, this clinical pattern also has been observed in other entities, such as angioimmunoblastic lymphoma, cutaneous Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and acanthosis nigricans.5,8,9

Specific characteristics of the rash and certain clinical symptoms may help to distinguish the deck-chair sign of PEO from its other causes. Although malignant acanthosis nigricans may spare the skinfolds, lesions have a classic velvety thickening and brownish hyperpigmentation, which is not characteristic of the reddish brown, flat-topped papules of PEO.9 Pai et al5 described a patient with parthenium dermatitis presenting with the deck-chair sign that developed years after repeated exposure to the allergen. Our patient did not have a history of repeated episodes of allergic contact dermatitis. In addition, areas of sparing may mimic the appearance of pityriasis rubra pilaris. As in our patient, those with PEO generally lack the follicular hyperkeratotic papules, palmoplantar keratoderma, widespread orange-red erythema, and characteristic histopathologic finding of hyperkeratosis with alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, allowing these entities to be easily distinguished in most instances.10

Histopathologically, primary PEO shows a nonspecific spongiotic dermatitis-like pattern characterized by slight epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and a predominantly perivascular dermal infiltrate with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils.3 These histologic findings may at times show some overlap with CTCL, and therefore T-cell gene rearrangement and flow cytometry may be performed in those instances.6

Treatment includes the management of any underlying condition causing the papuloerythroderma.3,6 There are no large clinical trials of treatment options for primary PEO due to its rarity. Topical or systemic corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment.3 Alternative treatments used with variable success include phototherapy, interferon, etretinate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine.11 Allegue et al11 successfully used methotrexate to treat a patient with primary PEO and postulated that methotrexate may act through an immunosuppressive mechanism on activated T cells due to the involvement of helper T cells TH2 and TH22 in its pathogenesis.

Although the cutaneous manifestations of PEO may respond well to topical steroids, it is important to consider the possible presence of an underlying malignancy and other associated systemic conditions.

The Diagnosis: Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji

The patient presented with a characteristic finding of skinfold sparing, known as the "deck-chair sign" (Figure 1).1 A repeat biopsy at our institution revealed a dermal perivascular and bandlike infiltrate with lymphocytes and occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). The epidermis showed mild spongiosis, lymphocytic exocytosis, and rare necrotic keratinocytes. A T-cell gene rearrangement assay was negative for a monoclonal population of T lymphocytes. Based on the clinical and histologic features, the diagnosis was most consistent with papuloerythroderma of Ofuji (PEO); however, a lymphoproliferative disorder needed to be excluded. Further workup included a peripheral smear, complete blood cell count with differential, comprehensive metabolic panel, IgE level, and hepatitis panel; all were normal, except for an elevated serum IgE level. Human immunodeficiency virus and age-appropriate malignancy screening were negative. The patient was prescribed betamethasone dipropionate cream 0.05% twice daily, which resulted in near-complete resolution of the rash and marked improvement in pruritus.

In 1984, PEO was described as an entity of generalized pruritic erythroderma characterized by flat-topped, red to brown, coalescing papules with sparing of the skinfolds, later coined the deck-chair sign.1,2 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji commonly presents in elderly Asian males with a male to female ratio of 4:1.3 Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji is a T cell-mediated skin disease; however, the etiology of the signature rash remains unclear. One explanation includes circulating factors in the skin that elicit an inflammatory response, which does not occur in areas of external pressure.3 The deck-chair sign may occur more frequently in elderly individuals due to increased skin laxity, which creates crease lines that are spared from rubbing and excoriations.4

Although Ofuji et al2 initially reported 4 idiopathic cases, subsequent authors described PEO in association with other conditions, including cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) and atopic diathesis, and infections, as well as secondary to medications. Some authors have suggested that PEO may be an early variant of mycosis fungoides; therefore, physicians should monitor patients closely.5-7 Maher et al6 commented that multiple causative factors including CTCL underlie the development of papuloerythroderma.

In a review of PEO, Torchia et al3 proposed diagnostic criteria and an etiologic classification to address whether PEO represents an independent entity or an unusual manifestation of other dermatoses. They established 4 categories of papuloerythroderma--primary, secondary, papuloerythrodermalike CTCL, and pseudopapuloerythroderma--and proposed that primary PEO is a diagnosis of exclusion. If no secondary association is found, they proposed 10 criteria for primary PEO: 5 major criteria include coalescing flat-topped papules, the deck-chair sign, pruritus, histopathologic exclusion of diseases such as CTCL, and a negative workup to exclude other causes.3 In 2018, Maher et al6 recommended workup to rule out cutaneous malignancy, including skin biopsy, flow cytometry, Sézary cell count, T-cell rearrangement, lactate dehydrogenase, and human T-cell lymphotropic virus 1. The 5 minor criteria proposed by Torchia et al3 include age older than 55 years, male sex, eosinophilia, elevated IgE level, and lymphopenia. Our patient fulfilled all 5 major criteria and 3 minor criteria; eosinophilia and lymphopenia were absent.

Clinically, PEO has been associated with the deck-chair sign, a pattern of selective sparing of skinfolds, including axillary, inguinal, submammary, and other flexural areas. Although the deck-chair sign was originally considered pathognomonic for PEO, this clinical pattern also has been observed in other entities, such as angioimmunoblastic lymphoma, cutaneous Waldenström macroglobulinemia, and acanthosis nigricans.5,8,9

Specific characteristics of the rash and certain clinical symptoms may help to distinguish the deck-chair sign of PEO from its other causes. Although malignant acanthosis nigricans may spare the skinfolds, lesions have a classic velvety thickening and brownish hyperpigmentation, which is not characteristic of the reddish brown, flat-topped papules of PEO.9 Pai et al5 described a patient with parthenium dermatitis presenting with the deck-chair sign that developed years after repeated exposure to the allergen. Our patient did not have a history of repeated episodes of allergic contact dermatitis. In addition, areas of sparing may mimic the appearance of pityriasis rubra pilaris. As in our patient, those with PEO generally lack the follicular hyperkeratotic papules, palmoplantar keratoderma, widespread orange-red erythema, and characteristic histopathologic finding of hyperkeratosis with alternating orthokeratosis and parakeratosis, allowing these entities to be easily distinguished in most instances.10

Histopathologically, primary PEO shows a nonspecific spongiotic dermatitis-like pattern characterized by slight epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and a predominantly perivascular dermal infiltrate with lymphocytes, histiocytes, and eosinophils.3 These histologic findings may at times show some overlap with CTCL, and therefore T-cell gene rearrangement and flow cytometry may be performed in those instances.6

Treatment includes the management of any underlying condition causing the papuloerythroderma.3,6 There are no large clinical trials of treatment options for primary PEO due to its rarity. Topical or systemic corticosteroids remain the mainstay of treatment.3 Alternative treatments used with variable success include phototherapy, interferon, etretinate, cyclosporine, and azathioprine.11 Allegue et al11 successfully used methotrexate to treat a patient with primary PEO and postulated that methotrexate may act through an immunosuppressive mechanism on activated T cells due to the involvement of helper T cells TH2 and TH22 in its pathogenesis.

Although the cutaneous manifestations of PEO may respond well to topical steroids, it is important to consider the possible presence of an underlying malignancy and other associated systemic conditions.

- Farthing CF, Staughton RC, Harper JI, et al. Papuloerythroderma--a further case with the 'deck chair sign.' Dermatologica. 1986;172:65-66.

- Ofuji S, Furukawa F, Miyachi Y, et al. Papuloerythroderma. Dermatologica. 1984;169:125-130.

- Torchia D, Miteva M, Hu S, et al. Papuloerythroderma 2009: two new cases and systematic review of the worldwide literature 25 years after its identification by Ofuji et al. Dermatology. 2010;220:311-320.

- Ochi H, Ang CC. Novel association of a papuloerythroderma of Ofuji phenotype with dermatitis herpetiformis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:856-857.

- Pai S, Shetty S, Rao R. Parthenium dermatitis with deck-chair sign. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:906-907.

- Maher AM, Ward CE, Glassman S, et al. The importance of excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in patients with a working diagnosis of papuloerythroderma of Ofuji: a case series. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:46-54.

- Grob JJ, Collet-Villette AM, Horchowski N, et al. Ofuji papuloerythroderma. report of a case with T cell skin lymphoma and discussion of the nature of this disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(5 pt 2):927-931.

- Ferran M, Gallardo F, Baena V, et al. The 'deck chair sign' in specific cutaneous involvement by angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Dermatology. 2006;213:50-52.

- Murao K, Sadamoto Y, Kubo Y, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans with "deck-chair sign." Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:377-378.

- Regina G, Paramita L, Radiono S, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji in Indonesia: the first case report. JDVI. 2016;1:93-98.

- Allegue F, Fachal C, Gonzalez-Vilas D, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji successfully treated with methotrexate. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12638.

- Farthing CF, Staughton RC, Harper JI, et al. Papuloerythroderma--a further case with the 'deck chair sign.' Dermatologica. 1986;172:65-66.

- Ofuji S, Furukawa F, Miyachi Y, et al. Papuloerythroderma. Dermatologica. 1984;169:125-130.

- Torchia D, Miteva M, Hu S, et al. Papuloerythroderma 2009: two new cases and systematic review of the worldwide literature 25 years after its identification by Ofuji et al. Dermatology. 2010;220:311-320.

- Ochi H, Ang CC. Novel association of a papuloerythroderma of Ofuji phenotype with dermatitis herpetiformis. Int J Dermatol. 2018;57:856-857.

- Pai S, Shetty S, Rao R. Parthenium dermatitis with deck-chair sign. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:906-907.

- Maher AM, Ward CE, Glassman S, et al. The importance of excluding cutaneous T-cell lymphomas in patients with a working diagnosis of papuloerythroderma of Ofuji: a case series. Case Rep Dermatol. 2018;10:46-54.

- Grob JJ, Collet-Villette AM, Horchowski N, et al. Ofuji papuloerythroderma. report of a case with T cell skin lymphoma and discussion of the nature of this disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989;20(5 pt 2):927-931.

- Ferran M, Gallardo F, Baena V, et al. The 'deck chair sign' in specific cutaneous involvement by angioimmunoblastic T cell lymphoma. Dermatology. 2006;213:50-52.

- Murao K, Sadamoto Y, Kubo Y, et al. Generalized malignant acanthosis nigricans with "deck-chair sign." Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:377-378.

- Regina G, Paramita L, Radiono S, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji in Indonesia: the first case report. JDVI. 2016;1:93-98.

- Allegue F, Fachal C, Gonzalez-Vilas D, et al. Papuloerythroderma of Ofuji successfully treated with methotrexate. Dermatol Ther. 2018;31:E12638.

An 89-year-old Asian man presented with a generalized pruritic eruption of 2 months' duration. The rash started on the flanks and later spread to the arms and legs, abdomen, and back; the face and palms were spared. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous papules coalescing into large scaly plaques on the trunk, arms, and legs. There were noticeable areas of sparing of the skinfolds, especially the axillary, inframammary, and inguinal folds, as well as the midline of the back. A biopsy performed by an outside physician showed findings consistent with a possible pityriasiform drug eruption; however, there were no recent changes in medication history.

Disseminated Vesicles and Necrotic Papules

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

The Diagnosis: Lues Maligna

Laboratory evaluation demonstrated a total CD4 count of 26 cells/μL (reference range, 443-1471 cells/μL) with a viral load of 1,770,111 copies/mL (reference range, 0 copies/mL), as well as a positive rapid plasma reagin (RPR) test with a titer of 1:8 (reference range, nonreactive). A reactive treponemal antibody test confirmed a true positive RPR test result. Viral culture as well as direct fluorescence antibodies for varicella-zoster virus and an active vesicle of herpes simplex virus (HSV) were negative. Serum immunoglobulin titers for varicella-zoster virus demonstrated low IgM with a positive IgG demonstrating immunity without recent infection. Blood and lesional skin tissue cultures were negative for additional infectious etiologies including bacterial and fungal elements. A lumbar puncture was not performed.

Biopsy of a papulonodule on the left arm demonstrated a lichenoid lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with superficial and deep inflammation (Figure 1). Neutrophils also were noted within a follicle with ballooning and acantholysis within the follicular epithelium. Additional staining for Mycobacterium, HSV-1, HSV-2, and Treponema were negative. In the clinical setting, this histologic pattern was most consistent with secondary syphilis. Pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta also was included in the histopathologic differential diagnosis by a dermatopathologist (M.C.).

Based on the clinical, microbiologic, and histopathologic findings, a diagnosis of lues maligna (cutaneous secondary syphilis) with a vesiculonecrotic presentation was made. The patient's low RPR titer was attributed to profound immunosuppression, while a confirmation of syphilis infection was made with treponemal antibody testing. Histopathologic examination was consistent with lues maligna and did not demonstrate evidence of any other infectious etiologies.

Following 7 days of intravenous penicillin, the patient demonstrated dramatic improvement of all skin lesions and was discharged receiving once-weekly intramuscular penicillin for 4 weeks. In accordance with the diagnosis, the patient demonstrated rapid improvement of the lesions following appropriate antibiotic therapy.

After the diagnosis of lues maligna was made, the patient disclosed a sexual encounter with a male partner 6 weeks prior to the current presentation, after which he developed a self-resolving genital ulcer suspicious for a primary chancre.

Increasing rates of syphilis transmission have been attributed to males aged 15 to 44 years who have sexual encounters with other males.1 Although syphilis commonly is known as the great mimicker, syphilology texts state that lesions are not associated with syphilis if vesicles are part of the cutaneous eruption in an adult.2 However, rare reports of secondary syphilis presenting as vesicles, pustules, bullae, and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta-like eruptions also have been documented.2-4

Initial screening for suspected syphilis involves sensitive, but not specific, nontreponemal RPR testing reported in the form of a titer. Nontreponemal titers in human immunodeficiency virus-positive individuals can be unusually high or low, fluctuate rapidly, and/or be unresponsive to antibiotic therapy.1

Lues maligna is a rare form of malignant secondary syphilis that most commonly presents in human immunodeficiency virus-positive hosts.5 Although lues maligna often presents with ulceronodular lesions, 2 cases presenting with vesiculonecrotic lesions also have been reported.6 Patients often experience systemic symptoms including fever, fatigue, and joint pain. Rapid plasma reagin titers can range from 1:8 to 1:128 in affected individuals.6 Diagnosis is dependent on serologic and histologic confirmation while ruling out viral, fungal, and bacterial etiologies. Characteristic red-brown lesions of secondary syphilis involving the palms and soles (Figure 2) alsoaid in diagnosis.1 Additionally, identification of the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction following treatment and rapid response to antibiotic therapy are helpful diagnostic findings.6,7 While histopathologic examination of lues maligna typically does not reveal evidence of spirochetes, it also is important to rule out other infectious etiologies.7

Our case emphasizes the importance of early recognition and treatment of the variable clinical, laboratory, and histologic presentations of lues maligna.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

- Syphilis fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/stdfact-syphilis.htm. Updated June 13, 2017. Accessed March 22, 2018.

- Lawrence P, Saxe N. Bullous secondary syphilis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1992;17:44-46.

- Pastuszczak M, Woz´niak W, Jaworek AK, et al. Pityriasis lichenoides-like secondary syphilis and neurosyphilis in a HIV-infected patient. Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2013;30:127-130.

- Schnirring-Judge M, Gustaferro C, Terol C. Vesiculobullous syphilis: a case involving an unusual cutaneous manifestation of secondary syphilis [published online November 24, 2010]. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50:96-101.

- Pföhler C, Koerner R, von Müller L, et al. Lues maligna in a patient with unknown HIV infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2011. pii: bcr0520114221. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2011.4221.

- Don PC, Rubinstein R, Christie S. Malignant syphilis (lues maligna) and concurrent infection with HIV. Int J Dermatol. 1995;34:403-407.

- Tucker JD, Shah S, Jarell AD, et al. Lues maligna in early HIV infection case report and review of the literature. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:512-514.

A 30-year-old man who had contracted human immunodeficiency virus from a male sexual partner 4 years prior presented to the emergency department with fevers, chills, night sweats, and rhinorrhea of 2 weeks' duration. He reported that he had been off highly active antiretroviral therapy for 2 years. Physical examination revealed numerous erythematous, papulonecrotic, crusted lesions on the face, neck, chest, back, arms, and legs that had developed over the past 4 days. Fluid-filled vesicles also were noted on the arms and legs, while erythematous, indurated nodules with overlying scaling were noted on the bilateral palms and soles. The patient reported that he had been vaccinated for varicella-zoster virus as a child without primary infection.