User login

Nutraceuticals for traumatic brain injury: Should you recommend their use?

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects more than 2 million people in the United States each year.1 TBI can trigger a cascade of secondary injury mechanisms, such as inflammation, hypoxic/ischemic injury, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress,2 that could contribute to cognitive and behavioral changes. Although neuropsychiatric symptoms might not be obvious after a TBI, they have a high prevalence in these patients, can last long term, and may be difficult to treat.3 Despite research advances in understanding the biological basis of TBI and identifying potential therapeutic targets, treatment options for individuals with TBI remain limited.

As a result, clinicians have turned to alternative treatments for TBI, including nutraceuticals. In this article, we will:

- provide an overview of nutraceuticals used in treating TBI, first exploring outcomes soon after TBI, then concentrating on neuropsychiatric outcomes

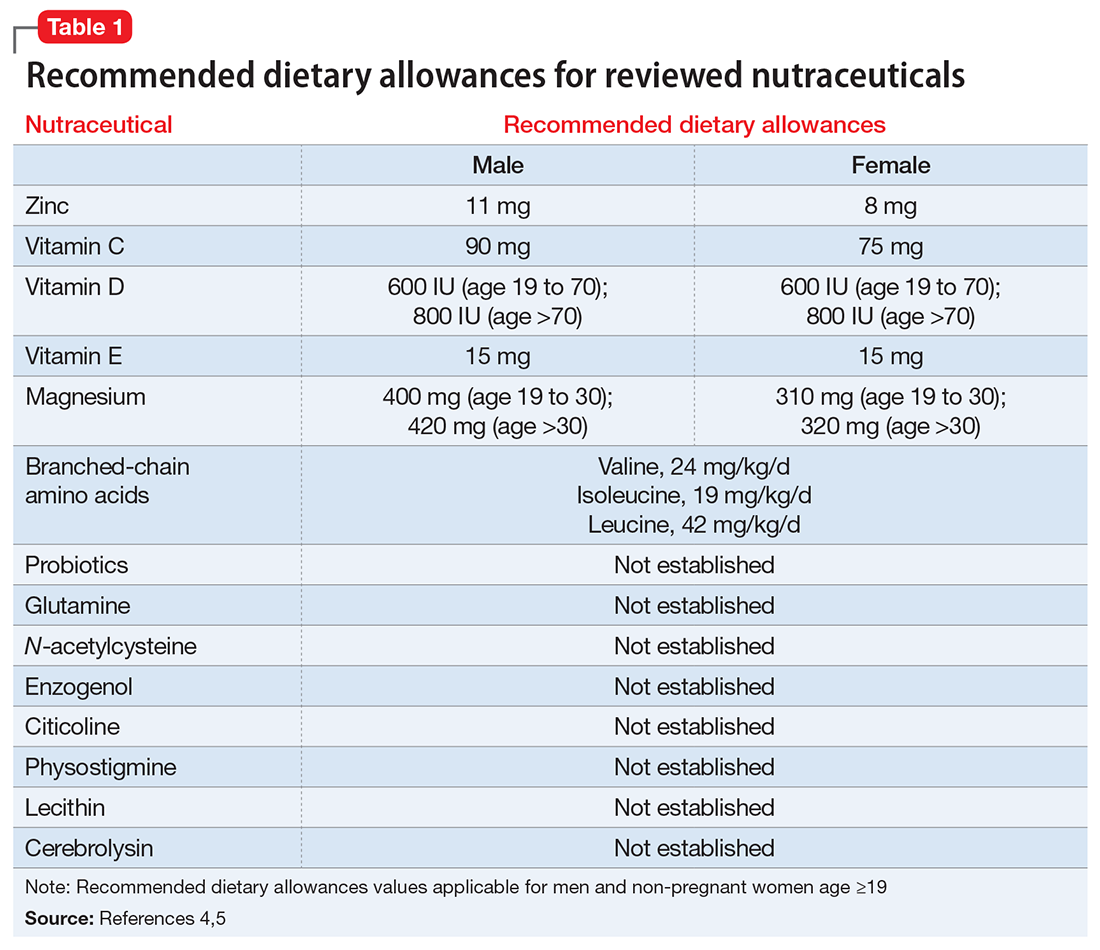

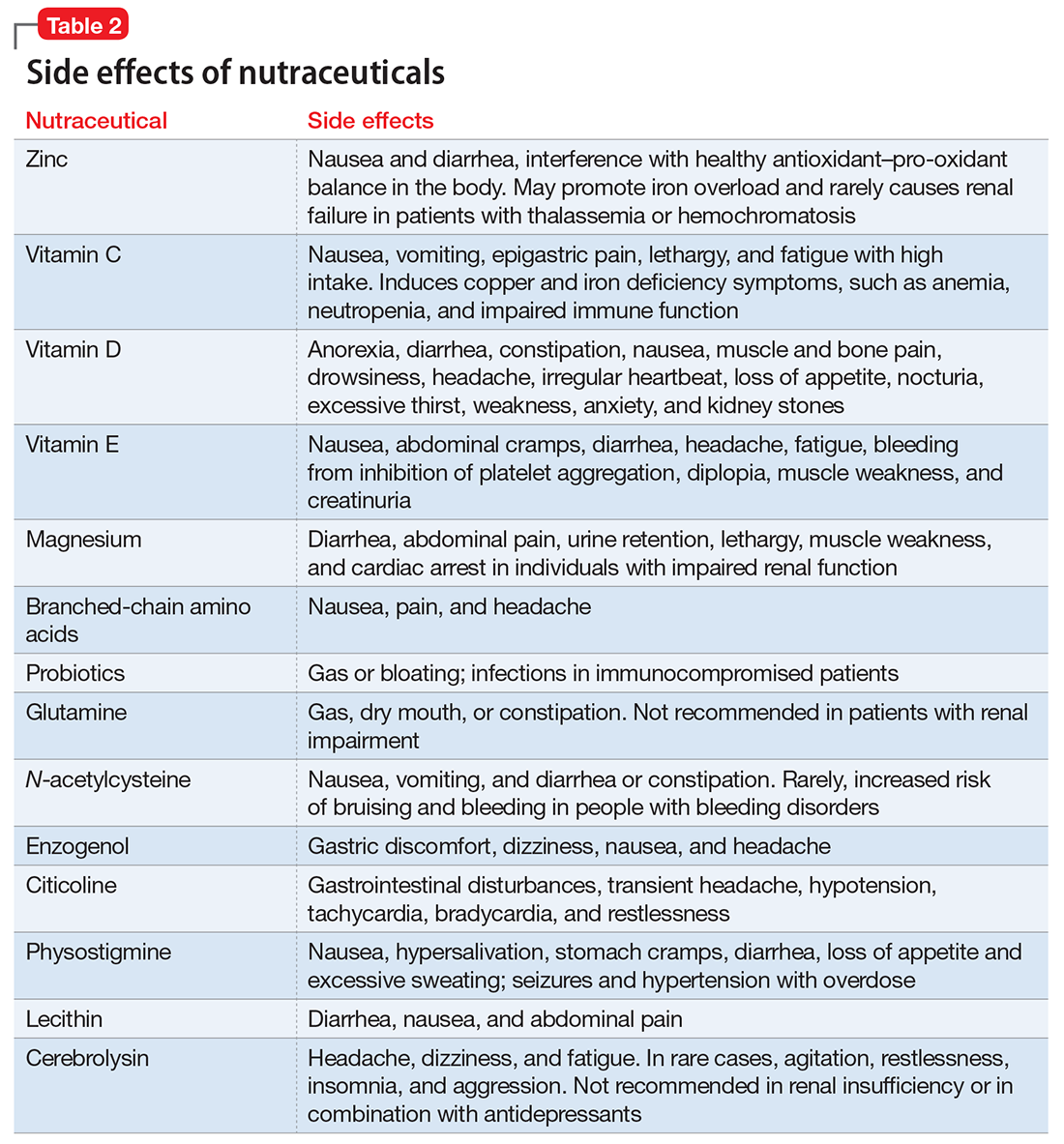

- evaluate the existing evidence, including recommended dietary allowances (Table 1)4,5 and side effects (Table 2)

- review recommendations for their clinical use.

Pharmacologic approaches are limited

Nutraceuticals have gained attention for managing TBI-associated neuropsychiatric disorders because of the limited evidence supporting current approaches. Existing strategies encompass pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions, psychoeducation, supportive and behavioral psychotherapies, and cognitive rehabilitation.6

Many pharmacologic options exist for specific neurobehavioral symptoms, but the evidence for their use is based on small studies, case reports, and knowledge extrapolated from their use in idiopathic psychiatric disorders.7,8 No FDA-approved drugs have been effective for treating neuropsychiatric disturbances after a TBI. Off-label use of antidepressants, anticonvulsants, dopaminergic agents, and cholinesterase inhibitors in TBI has been associated with inadequate clinical response and/or intolerable side effects.9,10

What are nutraceuticals?

DeFelice11 introduced the term “nutraceutical” to refer to “any substance that is a food or part of a food and provides medical or health benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease.” The term has been expanded to include dietary supplements, such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbal or other botanicals, and food products that provide health benefits beyond what they normally provide in food form. The FDA does not regulate the marketing or manufacturing of nutraceuticals; therefore, their bioavailability and metabolism can vary.

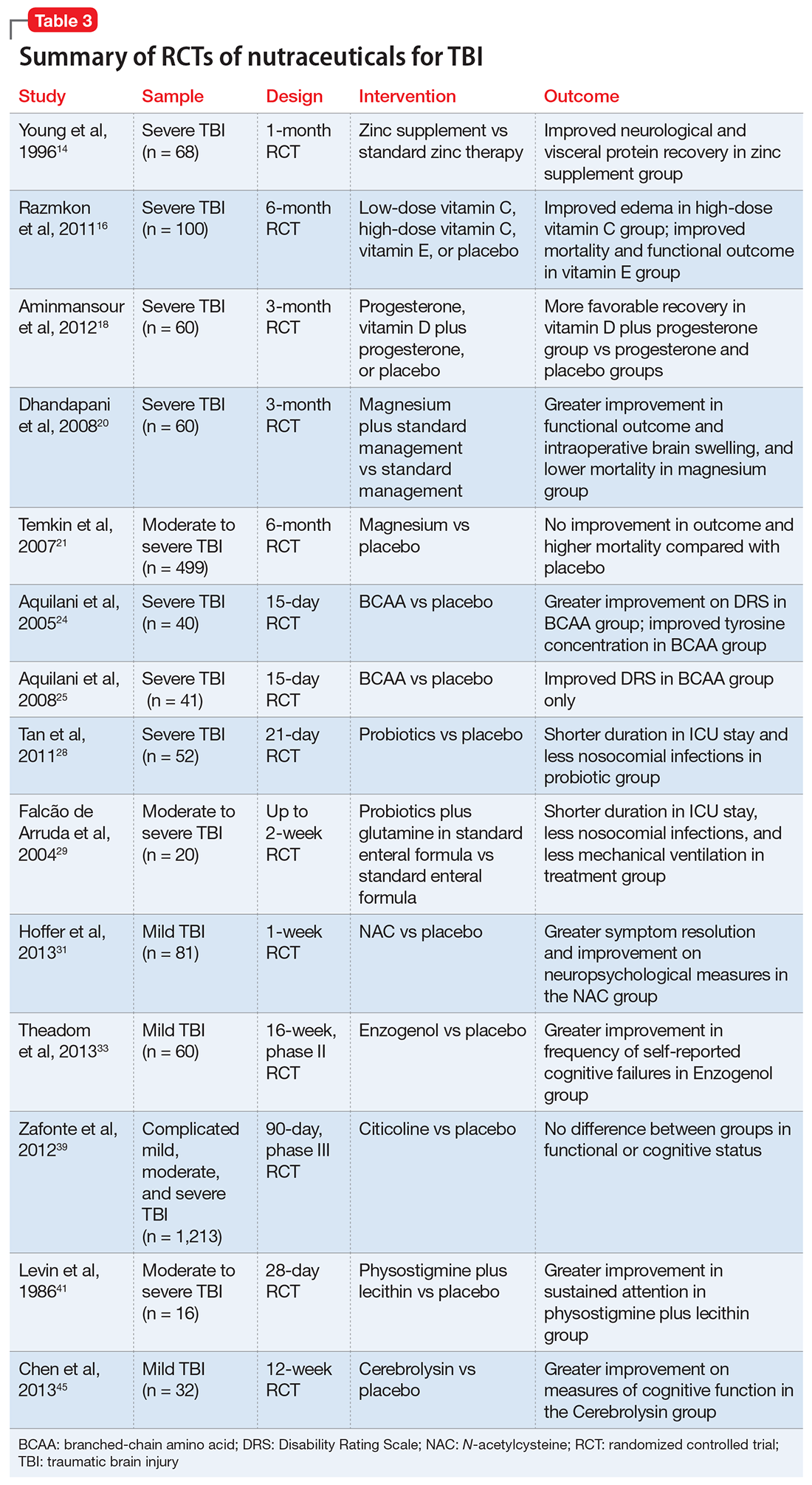

Despite their widespread use, the evidence supporting the efficacy of nutraceuticals for patients with TBI is limited. Their effects might vary by population and depend on dose, timing, TBI severity, and whether taken alone or in combination with other nutraceutical or pharmaceutical agents. Fourteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have addressed the use of nutraceuticals in TBI (Table 3), but further research is needed to clarify for which conditions they provide maximum benefit.

Nutraceuticals and their potential use in TBI

Zinc is considered essential for optimal CNS functioning. Patients with TBI might be at risk for zinc deficiency, which has been associated with increased cell death and behavioral deficits.12,13 A randomized, prospective, double-blinded controlled trial examined the effects of supplemental zinc administration (12 mg for 15 days) compared with standard zinc therapy (2.5 mg for 15 days) over 1 month in 68 adults with acute severe closed head injury.14 The supplemental zinc group showed improved visceral protein levels, lower mortality, and more favorable neurologic recovery based on higher adjusted mean Glasgow Coma Scale score on day 28 and mean motor score on days 15 and 21.

Rodent studies have shown that zinc supplementation could reduce deficits in spatial learning and memory and depression-like behaviors and help decrease stress and anxiety,12 although no human clinical trials have been conducted. Despite the potential neuroprotective effects of zinc supplementation, evidence exists that endogenous zinc release and accumulation following TBI can trigger cellular changes that result in neuronal death.13

Vitamins C and E. Oxidative damage is believed to play a significant role in secondary injury in TBI, so research has focused on the role of antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, to promote post-TBI recovery.15 One RCT16 of 100 adults with acute severe head injury reported that vitamin E administration was associated with reduced mortality and lower Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores, and vitamin C was associated with stabilized or reduced perilesional edema/infarct on CT scan.

Vitamin D. An animal study reported that vitamin D supplementation can help reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in TBI, and that vitamin D deficiency has been associated with increased inflammation and behavioral deficits.17 Further evidence suggests that vitamin D may have a synergistic effect when used in combination with the hormone progesterone. A RCT of 60 patients with severe TBI reported that 60% of those who received progesterone plus vitamin D had GOS scores of 4 (good recovery) or 5 (moderate disability) vs 45% receiving progesterone alone or 25% receiving placebo.18

Magnesium, one of the most widely used nutraceuticals, is considered essential for CNS functioning, including the regulation of N-methyl-

A RCT evaluated the safety and efficacy of magnesium supplementation in 60 patients with severe closed TBI, with one-half randomized to standard care and the other also receiving magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; initiation dose of 4 g IV and 10 g IM, continuation dose of 5 g IM every 4 hours for 24 hours).20 After 3 months, more patients in the MgSO4 group had higher GOS scores than controls (73.3% vs 40%), lower 1-month mortality rates (13.3% vs 43.3%), and lower rates of intraoperative brain swelling (29.4% vs 73.3%).

However, a larger RCT of 499 patients with moderate or severe TBI randomized to high-dose (1.25 to 2.5 mmol/L) or low-dose (1.0 to 1.85 mmol/L) IV MgSO4 or placebo provided conflicting results.21 Participants received MgSO4 8 hours after injury and continued for 5 days. After 6 months, patients in the high-dose MgSO4 and placebo groups had similar composite primary outcome measures (eg, seizures, neuropsychological measures, functional status measures), although the high-dose group had a higher mortality rate than the placebo group. Patients who received low-dose MgSO4 showed worse outcomes than those assigned to placebo.

Amino acids. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), including valine, isoleucine, and leucine, are essential in protein and neurotransmitter synthesis. Reduced levels of endogenous BCAAs have been reported in patients with mild or severe TBI.22 Preclinical studies suggest that BCAAs can improve hippocampal-dependent cognitive functioning following TBI.23

Two RCTs of BCAAs have been conducted in humans. One study randomized 40 men with severe TBI to IV BCAAs or placebo.24 After 15 days, the BCAA group showed greater improvement in Disability Rating Scale scores. The study also found that supplementation increased total BCAA levels without negatively affecting plasma levels of neurotransmitter precursors tyrosine and tryptophan. A second study found that 41 patients in a vegetative or minimally conscious state who received BCAA supplementation for 15 days had higher Disability Rating Scale scores than those receiving placebo.25

Probiotics and glutamine. Probiotics are non-pathogenic microorganisms that have been shown to modulate the host’s immune system.26 TBI is associated with immunological changes, including a shift from T-helper type 1 (TH1) cells to T-helper type 2 (TH2) cells that increase susceptibility to infection.27

A RCT of 52 patients with severe TBI suggested a correlation between probiotic administration-modulated cytokine levels and TH1/TH2 balance.28 A 3-times daily probiotic mix of Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophilus for 21 days led to shorter average ICU stays (6.8 vs 10.7 days, P = .034) and a decrease in nosocomial infections (34.6% vs 57.7%, P = .095) vs placebo, although the latter difference was not statistically significant.28

A prospective RCT of 20 patients with brain injury29 found a similar impact of early enteral nutrition supplemented with Lactobacillus johnsonii and glutamine, 30 g, vs a standard enteral nutrition formula. The treatment group experienced fewer nosocomial infections (50% vs 100%, P = .03), shorter ICU stays (10 vs 22 days, P < .01), and fewer days on mechanical ventilation (7 vs 14, P = .04). Despite these studies, evidence for the use of glutamine in patients with TBI is scarce and inconclusive.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) comes from the amino acid L-cysteine. NAC is an effective scavenger of free radicals and improves cerebral microcirculatory blood flow and tissue oxygenation.30 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral NAC supplementation in 81 active duty service members with mild TBI found NAC had a significant effect on outcomes.31 Oral NAC supplementation led to improved neuropsychological test results, number of mild TBI symptoms, complete symptom resolution by day 7 of treatment compared with placebo, and NAC was well tolerated. Lack of replication studies and generalizability of findings to civilian, moderate, or chronic TBI populations are key limitations of this study.

Proposed mechanisms for the neuroprotective benefit of NAC include its antioxidant and inflammatory activation of cysteine/glutamate exchange, metabotropic glutamate receptor modulation, and glutathione synthesis.32 NAC has poor blood–brain permeability, but the vascular disruption seen in acute TBI might facilitate its delivery to affected neural sites.31 As such, the benefits of NAC in subacute or chronic TBI are questionable.

Neuropsychiatric outcomes of nutraceuticals

Enzogenol. This flavonoid-rich extract from the bark of the Monterey pine tree (Pinus radiata), known by the trade name Enzogenol, reportedly has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may counter oxidative damage and neuroinflammation following TBI. A phase II trial randomized participants to Enzogenol, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo for 6 weeks, then all participants received Enzogenol for 6 weeks followed by placebo for 4 weeks.33 Enzogenol was well tolerated with few side effects.

Compared with placebo, participants receiving Enzogenol showed no significant change in mood, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and greater improvement in overall cognition as assessed by the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. However, measures of working memory (digit span, arithmetic, and letter–number sequencing subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) and episodic memory (California Verbal Learning Test) showed no benefit from Enzogenol.

Citicoline (CDP-choline) is an endogenous compound widely available as a nutraceutical that has been approved for TBI therapy in 59 countries.34 Animal studies indicate that it could possess neuroprotective properties. Proposed mechanisms for such effects have included stabilizing cell membranes, reducing inflammation, reducing the presence of free radicals, or stimulating production of acetylcholine.35,36 A study in rats found that CDP-choline was associated with increased levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus and neocortex, which may help reduce neurobehavioral deficits.37

A study of 14 adults with mild to moderate closed head injury38 found that patients who received CDP-choline showed a greater reduction in post-concussion symptoms and improvement in recognition memory than controls who received placebo. However, the Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial, a large randomized trial of 1,213 adults with complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI, reported that CDP-choline did not improve functional and cognitive status.39

Physostigmine and lecithin. The cholinergic system is a key modulatory neurotransmitter system of the brain that mediates conscious awareness, attention, learning, and working memory.40 A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 16 patients with moderate to severe closed head injury provided inconsistent evidence for the efficacy of physostigmine and lecithin in the treatment of memory and attention disturbances.41The results showed no differences between the physostigmine–lecithin combination vs lecithin alone, although sustained attention on the Continuous Performance Test was more efficient with physostigmine than placebo when the drug condition occurred first in the crossover design. The lack of encouraging data and concerns about its cardiovascular and proconvulsant properties in patients with TBI may explain the dearth of studies with physostigmine.

Cerebrolysin. A peptide preparation produced from purified pig brain proteins, known by the trade name Cerebrolysin, is popular in Asia and Europe for its nootropic properties. Cerebrolysin may activate cerebral mechanisms related to attention and memory processes,42 and some data have shown efficacy in improving cognitive symptoms and daily activities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease43 and TBI.44

A blinded 12-week study of 32 participants with acute mild TBI reported that those randomized to Cerebrolysin showed improvement in cognitive functioning vs the placebo group.45 The authors concluded that Cerebrolysin provides an advantage for patients with mild TBI and brain contusion if treatment starts within 24 hours of mild TBI onset. Cerebrolysin was well tolerated. Major limitations of this study were small sample size, lack of information regarding comorbid neuropsychiatric conditions and treatments, and short treatment duration.

A recent Cochrane review of 6 RCTs with 1,501 participants found no clinical benefit of Cerebrolysin for treating acute ischemic stroke, and found moderate-quality evidence of an increase with non-fatal serious adverse events but not in total serious adverse events.46 We do not recommend Cerebrolysin use in patients with TBI at this time until additional efficacy and safety data are available.

Nutraceuticals used in other populations

Other nutraceuticals with preclinical evidence of possible benefit in TBI but lacking evidence from human clinical trials include omega-3 fatty acids,47 curcumin,48 and resveratrol,49 providing further proof that results from experimental studies do not necessarily extend to clinical trials.50

Studies of nutraceuticals in other neurological and psychiatric populations have yielded some promising results. Significant interest has focused on the association between vitamin D deficiency, dementia, and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease.51 The role of vitamin D in regulation of calcium-mediated neuronal excitotoxicity and oxidative stress and in the induction of synaptic structural proteins, neurotrophic factors, and deficient neurotransmitters makes it an attractive candidate as a neuroprotective agent.52

RCTs of nutraceuticals also have reported positive findings for a variety of mood and anxiety disorders, such as St. John’s wort, S-adenosylmethionine, omega-3 fatty acids for major depression53 and bipolar depression,54 and kava for generalized anxiety disorder.55 More research, however, is needed in these areas.

The use of nonpharmacologic agents in TBI often relies on similar neuropsychiatric symptom profiles of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) closely resembles TBI, but systemic reviews of studies of zinc, magnesium, and polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in ADHD provide no evidence of therapeutic benefit.56-58

Educate patients in role of nutraceuticals

Despite lack of FDA oversight and limited empirical support, nutraceuticals continue to be widely marketed and used for their putative health benefits59 and have gained increased attention among clinicians.60 Because nutritional deficiency may make the brain less able than other organs to recover from injury,61 supplementation is an option, especially in individuals who could be at greater risk of TBI (eg, athletes and military personnel).

Lacking robust scientific evidence to support the use of nutraceuticals either for enhancing TBI recovery or treating neuropsychiatric disturbances, clinicians must educate patients that these agents are not completely benign and can have significant side effects and drug interactions.62,63 Nutraceuticals may contain multiple ingredients, some of which can be toxic, particularly at higher doses. Many patients may not volunteer information about their nutraceutical use to their health care providers,64 so we must ask them about that and inform them of the potential for adverse events and drug interactions.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pubs/congress_epi_rehab.html. Updated January 22, 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(1):4-9.

3. Vaishnavi S, Rao V, Fann JR. Neuropsychiatric problems after traumatic brain injury: unraveling the silent epidemic. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):198-205.

4. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all. Accessed June 5, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2002.

6. Rao V, Koliatsos V, Ahmed F, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with traumatic brain injury: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(1):64-82.

7. Chew E, Zafonte RD. Pharmacological management of neurobehavioral disorders following traumatic brain injury—a state-of-the-art review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):851-879.

8. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533; discussion 1533.

9. Bengtsson M, Godbolt AK. Effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on cognitive function in patients with chronic traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(1):1-5.

10. Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working Group; Warden DL, Gordon B, McAllister TW, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1468-1501.

11. DeFelice SL. The nutraceutical revolution: its impact on food industry R&D. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1995;6(2):59-61.

12. Cope EC, Morris DR, Levenson CW. Improving treatments and outcomes: an emerging role for zinc in traumatic brain injury. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(7):410-413.

13. Morris DR, Levenson CW. Zinc in traumatic brain injury: from neuroprotection to neurotoxicity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(6):708-711.

14. Young B, Ott L, Kasarskis E, et al. Zinc supplementation is associated with improved neurologic recovery rate and visceral protein levels of patients with severe closed head injury. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13(1):25-34.

15. Fernández-Gajardo R, Matamala JM, Carrasco R, et al. Novel therapeutic strategies for traumatic brain injury: acute antioxidant reinforcement. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(3):229-248.

16. Razmkon A, Sadidi A, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh E, et al. Administration of vitamin C and vitamin E in severe head injury: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin Neurosurg. 2011;58:133-137.

17. Cekic M, Cutler SM, VanLandingham JW, et al. Vitamin D deficiency reduces the benefits of progesterone treatment after brain injury in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(5):864-874.

18. Aminmansour B, Nikbakht H, Ghorbani A, et al. Comparison of the administration of progesterone versus progesterone and vitamin D in improvement of outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trial with placebo group. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:58.

19. Cernak I, Savic VJ, Kotur J, et al. Characterization of plasma magnesium concentration and oxidative stress following graded traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(1):53-68.

20. Dhandapani SS, Gupta A, Vivekanandhan S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of magnesium sulphate in severe closed traumatic brain injury. The Indian Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008;5(1):27-33.

21. Temkin NR, Anderson GD, Winn HR, et al. Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(1):29-38.

22. Jeter CB, Hergenroeder GW, Ward NH 3rd, et al. Human mild traumatic brain injury decreases circulating branched-chain amino acids and their metabolite levels. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(8):671-679.

23. Cole JT, Mitala CM, Kundu S, et al. Dietary branched chain amino acids ameliorate injury-induced cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(1):366-371.

24. Aquilani R, Iadarola P, Contardi A, et al. Branched-chain amino acids enhance the cognitive recovery of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(9):1729-1735.

25. Aquilani R, Boselli M, Boschi F, et al. Branched-chain amino acids may improve recovery from a vegetative or minimally conscious state in patients with traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1642-1647.

26. Kang HJ, Im SH. Probiotics as an immune modulator. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2015;61(suppl):S103-S105.

27. DiPiro JT, Howdieshell TR, Goddard JK, et al. Association of interleukin-4 plasma levels with traumatic injury and clinical course. Arch Surg. 1995;130(11):1159-1162; discussion 1162-1163.

28. Tan M, Zhu JC, Du J, et al. Effects of probiotics on serum levels of Th1/Th2 cytokine and clinical outcomes in severe traumatic brain-injured patients: a prospective randomized pilot study. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R290.

29. Falcão de Arruda IS, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Benefits of early enteral nutrition with glutamine and probiotics in brain injury patients. Clin Sci (Lond). 2004;106(3):287-292.

30. Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Costantino G, et al. Beneficial effects of n-acetylcysteine on ischaemic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130(6):1219-1226.

31. Hoffer ME, Balaban C, Slade MD, et al. Amelioration of acute sequelae of blast induced mild traumatic brain injury by N-acetyl cysteine: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54163.

32. Eakin K, Baratz-Goldstein R, Pick CG, et al. Efficacy of N-acetyl cysteine in traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e90617.

33. Theadom A, Mahon S, Barker-Collo S, et al. Enzogenol for cognitive functioning in traumatic brain injury: a pilot placebo-controlled RCT. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(8):1135-1144.

34. Arenth PM, Russell KC, Ricker JH, et al. CDP-choline as a biological supplement during neurorecovery: a focused review. PM R. 2011;3(6 suppl 1):S123-S131.

35. Clark WM. Efficacy of citicoline as an acute stroke treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(5):839-846.

36. Guseva MV, Hopkins DM, Scheff SW, et al. Dietary choline supplementation improves behavioral, histological, and neurochemical outcomes in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(8):975-983.

37. Dixon CE, Ma X, Marion DW. Effects of CDP-choline treatment on neurobehavioral deficits after TBI and on hippocampal and neocortical acetylcholine release. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14(3):161-169.

38. Levin HS. Treatment of postconcussional symptoms with CDP-choline. J Neurol Sci. 1991;103(suppl):S39-S42.

39. Zafonte RD, Bagiella E, Ansel BM, et al. Effect of citicoline on functional and cognitive status among patients with traumatic brain injury: Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial (COBRIT). JAMA. 2012;308(19):1993-2000.

40. Perry E, Walker M, Grace J, et al. Acetylcholine in mind: a neurotransmitter correlate of consciousness? Trends Neurosci. 1999;22(6):273-280.

41. Levin HS, Peters BH, Kalisky Z, et al. Effects of oral physostigmine and lecithin on memory and attention in closed head-injured patients. Cent Nerv Syst Trauma. 1986;3(4):333-342.

42. Alvarez XA, Lombardi VR, Corzo L, et al. Oral cerebrolysin enhances brain alpha activity and improves cognitive performance in elderly control subjects. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:315-328.

43. Ruether E, Husmann R, Kinzler E, et al. A 28-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with cerebrolysin in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(5):253-263.

44. Wong GK, Zhu XL, Poon WS. Beneficial effect of cerebrolysin on moderate and severe head injury patients: result of a cohort study. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:59-60.

45. Chen CC, Wei ST, Tsaia SC, et al. Cerebrolysin enhances cognitive recovery of mild traumatic brain injury patients: double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(6):803-807.

46. Ziganshina LE, Abakumova T, Vernay L. Cerebrolysin for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD007026.

47. Barrett EC, McBurney MI, Ciappio ED. ω-3 fatty acid supplementation as a potential therapeutic aid for the recovery from mild traumatic brain injury/concussion. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(3):268-277.

48. Sharma S, Zhuang Y, Ying Z, et al. Dietary curcumin supplementation counteracts reduction in levels of molecules involved in energy homeostasis after brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2009;161(4):1037-1044.

49. Gatson JW, Liu MM, Abdelfattah K, et al. Resveratrol decreases inflammation in the brain of mice with mild traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):470-475; discussion 474-475.

50. Grey A, Bolland M. Clinical trial evidence and use of fish oil supplements. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):460-462.

51. Mpandzou G, Aït Ben Haddou E, Regragui W, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and its role in neurological conditions: a review. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2016;172(2):109-122.

52. Karakis I, Pase MP, Beiser A, et al. Association of serum vitamin D with the risk of incident dementia and subclinical indices of brain aging: The Framingham Heart Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(2):451-461.

53. Sarris J, Papakostas GI, Vitolo O, et al. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) versus escitalopram and placebo in major depression RCT: efficacy and effects of histamine and carnitine as moderators of response. J Affect Disord. 2014;164:76-81.

54. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

55. Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman C, et al. Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(5):643-648.

56. Hariri M, Azadbakht L. Magnesium, iron, and zinc supplementation for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review on the recent literature. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:83.

57. Gillies D, Sinn JKh, Lad SS, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007986.

58. Ghanizadeh A, Berk M. Zinc for treating of children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):122-124.

59. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Can a dietary supplement treat a concussion? No! http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm378845.htm. Updated February 13, 2015. Accessed June 5, 2017.

60. Sarris J, Logan AC, Akbaraly TN, et al; International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):271-274.

61. Desai A, Kevala K, Kim HY. Depletion of brain docosahexaenoic acid impairs recovery from traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86472.

62. Edie CF, Dewan N. Which psychotropics interact with four common supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):16-30.

63. Di Lorenzo C, Ceschi A, Kupferschmidt H, et al. Adverse effects of plant food supplements and botanical preparations: a systematic review with critical evaluation of causality. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(4):578-592.

64. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary and alternative medicine: what people aged 50 and older discuss with their health care providers. https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/2010. Published 2011. Accessed June 5, 2017.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects more than 2 million people in the United States each year.1 TBI can trigger a cascade of secondary injury mechanisms, such as inflammation, hypoxic/ischemic injury, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress,2 that could contribute to cognitive and behavioral changes. Although neuropsychiatric symptoms might not be obvious after a TBI, they have a high prevalence in these patients, can last long term, and may be difficult to treat.3 Despite research advances in understanding the biological basis of TBI and identifying potential therapeutic targets, treatment options for individuals with TBI remain limited.

As a result, clinicians have turned to alternative treatments for TBI, including nutraceuticals. In this article, we will:

- provide an overview of nutraceuticals used in treating TBI, first exploring outcomes soon after TBI, then concentrating on neuropsychiatric outcomes

- evaluate the existing evidence, including recommended dietary allowances (Table 1)4,5 and side effects (Table 2)

- review recommendations for their clinical use.

Pharmacologic approaches are limited

Nutraceuticals have gained attention for managing TBI-associated neuropsychiatric disorders because of the limited evidence supporting current approaches. Existing strategies encompass pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions, psychoeducation, supportive and behavioral psychotherapies, and cognitive rehabilitation.6

Many pharmacologic options exist for specific neurobehavioral symptoms, but the evidence for their use is based on small studies, case reports, and knowledge extrapolated from their use in idiopathic psychiatric disorders.7,8 No FDA-approved drugs have been effective for treating neuropsychiatric disturbances after a TBI. Off-label use of antidepressants, anticonvulsants, dopaminergic agents, and cholinesterase inhibitors in TBI has been associated with inadequate clinical response and/or intolerable side effects.9,10

What are nutraceuticals?

DeFelice11 introduced the term “nutraceutical” to refer to “any substance that is a food or part of a food and provides medical or health benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease.” The term has been expanded to include dietary supplements, such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbal or other botanicals, and food products that provide health benefits beyond what they normally provide in food form. The FDA does not regulate the marketing or manufacturing of nutraceuticals; therefore, their bioavailability and metabolism can vary.

Despite their widespread use, the evidence supporting the efficacy of nutraceuticals for patients with TBI is limited. Their effects might vary by population and depend on dose, timing, TBI severity, and whether taken alone or in combination with other nutraceutical or pharmaceutical agents. Fourteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have addressed the use of nutraceuticals in TBI (Table 3), but further research is needed to clarify for which conditions they provide maximum benefit.

Nutraceuticals and their potential use in TBI

Zinc is considered essential for optimal CNS functioning. Patients with TBI might be at risk for zinc deficiency, which has been associated with increased cell death and behavioral deficits.12,13 A randomized, prospective, double-blinded controlled trial examined the effects of supplemental zinc administration (12 mg for 15 days) compared with standard zinc therapy (2.5 mg for 15 days) over 1 month in 68 adults with acute severe closed head injury.14 The supplemental zinc group showed improved visceral protein levels, lower mortality, and more favorable neurologic recovery based on higher adjusted mean Glasgow Coma Scale score on day 28 and mean motor score on days 15 and 21.

Rodent studies have shown that zinc supplementation could reduce deficits in spatial learning and memory and depression-like behaviors and help decrease stress and anxiety,12 although no human clinical trials have been conducted. Despite the potential neuroprotective effects of zinc supplementation, evidence exists that endogenous zinc release and accumulation following TBI can trigger cellular changes that result in neuronal death.13

Vitamins C and E. Oxidative damage is believed to play a significant role in secondary injury in TBI, so research has focused on the role of antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, to promote post-TBI recovery.15 One RCT16 of 100 adults with acute severe head injury reported that vitamin E administration was associated with reduced mortality and lower Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores, and vitamin C was associated with stabilized or reduced perilesional edema/infarct on CT scan.

Vitamin D. An animal study reported that vitamin D supplementation can help reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in TBI, and that vitamin D deficiency has been associated with increased inflammation and behavioral deficits.17 Further evidence suggests that vitamin D may have a synergistic effect when used in combination with the hormone progesterone. A RCT of 60 patients with severe TBI reported that 60% of those who received progesterone plus vitamin D had GOS scores of 4 (good recovery) or 5 (moderate disability) vs 45% receiving progesterone alone or 25% receiving placebo.18

Magnesium, one of the most widely used nutraceuticals, is considered essential for CNS functioning, including the regulation of N-methyl-

A RCT evaluated the safety and efficacy of magnesium supplementation in 60 patients with severe closed TBI, with one-half randomized to standard care and the other also receiving magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; initiation dose of 4 g IV and 10 g IM, continuation dose of 5 g IM every 4 hours for 24 hours).20 After 3 months, more patients in the MgSO4 group had higher GOS scores than controls (73.3% vs 40%), lower 1-month mortality rates (13.3% vs 43.3%), and lower rates of intraoperative brain swelling (29.4% vs 73.3%).

However, a larger RCT of 499 patients with moderate or severe TBI randomized to high-dose (1.25 to 2.5 mmol/L) or low-dose (1.0 to 1.85 mmol/L) IV MgSO4 or placebo provided conflicting results.21 Participants received MgSO4 8 hours after injury and continued for 5 days. After 6 months, patients in the high-dose MgSO4 and placebo groups had similar composite primary outcome measures (eg, seizures, neuropsychological measures, functional status measures), although the high-dose group had a higher mortality rate than the placebo group. Patients who received low-dose MgSO4 showed worse outcomes than those assigned to placebo.

Amino acids. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), including valine, isoleucine, and leucine, are essential in protein and neurotransmitter synthesis. Reduced levels of endogenous BCAAs have been reported in patients with mild or severe TBI.22 Preclinical studies suggest that BCAAs can improve hippocampal-dependent cognitive functioning following TBI.23

Two RCTs of BCAAs have been conducted in humans. One study randomized 40 men with severe TBI to IV BCAAs or placebo.24 After 15 days, the BCAA group showed greater improvement in Disability Rating Scale scores. The study also found that supplementation increased total BCAA levels without negatively affecting plasma levels of neurotransmitter precursors tyrosine and tryptophan. A second study found that 41 patients in a vegetative or minimally conscious state who received BCAA supplementation for 15 days had higher Disability Rating Scale scores than those receiving placebo.25

Probiotics and glutamine. Probiotics are non-pathogenic microorganisms that have been shown to modulate the host’s immune system.26 TBI is associated with immunological changes, including a shift from T-helper type 1 (TH1) cells to T-helper type 2 (TH2) cells that increase susceptibility to infection.27

A RCT of 52 patients with severe TBI suggested a correlation between probiotic administration-modulated cytokine levels and TH1/TH2 balance.28 A 3-times daily probiotic mix of Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophilus for 21 days led to shorter average ICU stays (6.8 vs 10.7 days, P = .034) and a decrease in nosocomial infections (34.6% vs 57.7%, P = .095) vs placebo, although the latter difference was not statistically significant.28

A prospective RCT of 20 patients with brain injury29 found a similar impact of early enteral nutrition supplemented with Lactobacillus johnsonii and glutamine, 30 g, vs a standard enteral nutrition formula. The treatment group experienced fewer nosocomial infections (50% vs 100%, P = .03), shorter ICU stays (10 vs 22 days, P < .01), and fewer days on mechanical ventilation (7 vs 14, P = .04). Despite these studies, evidence for the use of glutamine in patients with TBI is scarce and inconclusive.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) comes from the amino acid L-cysteine. NAC is an effective scavenger of free radicals and improves cerebral microcirculatory blood flow and tissue oxygenation.30 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral NAC supplementation in 81 active duty service members with mild TBI found NAC had a significant effect on outcomes.31 Oral NAC supplementation led to improved neuropsychological test results, number of mild TBI symptoms, complete symptom resolution by day 7 of treatment compared with placebo, and NAC was well tolerated. Lack of replication studies and generalizability of findings to civilian, moderate, or chronic TBI populations are key limitations of this study.

Proposed mechanisms for the neuroprotective benefit of NAC include its antioxidant and inflammatory activation of cysteine/glutamate exchange, metabotropic glutamate receptor modulation, and glutathione synthesis.32 NAC has poor blood–brain permeability, but the vascular disruption seen in acute TBI might facilitate its delivery to affected neural sites.31 As such, the benefits of NAC in subacute or chronic TBI are questionable.

Neuropsychiatric outcomes of nutraceuticals

Enzogenol. This flavonoid-rich extract from the bark of the Monterey pine tree (Pinus radiata), known by the trade name Enzogenol, reportedly has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may counter oxidative damage and neuroinflammation following TBI. A phase II trial randomized participants to Enzogenol, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo for 6 weeks, then all participants received Enzogenol for 6 weeks followed by placebo for 4 weeks.33 Enzogenol was well tolerated with few side effects.

Compared with placebo, participants receiving Enzogenol showed no significant change in mood, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and greater improvement in overall cognition as assessed by the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. However, measures of working memory (digit span, arithmetic, and letter–number sequencing subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) and episodic memory (California Verbal Learning Test) showed no benefit from Enzogenol.

Citicoline (CDP-choline) is an endogenous compound widely available as a nutraceutical that has been approved for TBI therapy in 59 countries.34 Animal studies indicate that it could possess neuroprotective properties. Proposed mechanisms for such effects have included stabilizing cell membranes, reducing inflammation, reducing the presence of free radicals, or stimulating production of acetylcholine.35,36 A study in rats found that CDP-choline was associated with increased levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus and neocortex, which may help reduce neurobehavioral deficits.37

A study of 14 adults with mild to moderate closed head injury38 found that patients who received CDP-choline showed a greater reduction in post-concussion symptoms and improvement in recognition memory than controls who received placebo. However, the Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial, a large randomized trial of 1,213 adults with complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI, reported that CDP-choline did not improve functional and cognitive status.39

Physostigmine and lecithin. The cholinergic system is a key modulatory neurotransmitter system of the brain that mediates conscious awareness, attention, learning, and working memory.40 A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 16 patients with moderate to severe closed head injury provided inconsistent evidence for the efficacy of physostigmine and lecithin in the treatment of memory and attention disturbances.41The results showed no differences between the physostigmine–lecithin combination vs lecithin alone, although sustained attention on the Continuous Performance Test was more efficient with physostigmine than placebo when the drug condition occurred first in the crossover design. The lack of encouraging data and concerns about its cardiovascular and proconvulsant properties in patients with TBI may explain the dearth of studies with physostigmine.

Cerebrolysin. A peptide preparation produced from purified pig brain proteins, known by the trade name Cerebrolysin, is popular in Asia and Europe for its nootropic properties. Cerebrolysin may activate cerebral mechanisms related to attention and memory processes,42 and some data have shown efficacy in improving cognitive symptoms and daily activities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease43 and TBI.44

A blinded 12-week study of 32 participants with acute mild TBI reported that those randomized to Cerebrolysin showed improvement in cognitive functioning vs the placebo group.45 The authors concluded that Cerebrolysin provides an advantage for patients with mild TBI and brain contusion if treatment starts within 24 hours of mild TBI onset. Cerebrolysin was well tolerated. Major limitations of this study were small sample size, lack of information regarding comorbid neuropsychiatric conditions and treatments, and short treatment duration.

A recent Cochrane review of 6 RCTs with 1,501 participants found no clinical benefit of Cerebrolysin for treating acute ischemic stroke, and found moderate-quality evidence of an increase with non-fatal serious adverse events but not in total serious adverse events.46 We do not recommend Cerebrolysin use in patients with TBI at this time until additional efficacy and safety data are available.

Nutraceuticals used in other populations

Other nutraceuticals with preclinical evidence of possible benefit in TBI but lacking evidence from human clinical trials include omega-3 fatty acids,47 curcumin,48 and resveratrol,49 providing further proof that results from experimental studies do not necessarily extend to clinical trials.50

Studies of nutraceuticals in other neurological and psychiatric populations have yielded some promising results. Significant interest has focused on the association between vitamin D deficiency, dementia, and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease.51 The role of vitamin D in regulation of calcium-mediated neuronal excitotoxicity and oxidative stress and in the induction of synaptic structural proteins, neurotrophic factors, and deficient neurotransmitters makes it an attractive candidate as a neuroprotective agent.52

RCTs of nutraceuticals also have reported positive findings for a variety of mood and anxiety disorders, such as St. John’s wort, S-adenosylmethionine, omega-3 fatty acids for major depression53 and bipolar depression,54 and kava for generalized anxiety disorder.55 More research, however, is needed in these areas.

The use of nonpharmacologic agents in TBI often relies on similar neuropsychiatric symptom profiles of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) closely resembles TBI, but systemic reviews of studies of zinc, magnesium, and polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in ADHD provide no evidence of therapeutic benefit.56-58

Educate patients in role of nutraceuticals

Despite lack of FDA oversight and limited empirical support, nutraceuticals continue to be widely marketed and used for their putative health benefits59 and have gained increased attention among clinicians.60 Because nutritional deficiency may make the brain less able than other organs to recover from injury,61 supplementation is an option, especially in individuals who could be at greater risk of TBI (eg, athletes and military personnel).

Lacking robust scientific evidence to support the use of nutraceuticals either for enhancing TBI recovery or treating neuropsychiatric disturbances, clinicians must educate patients that these agents are not completely benign and can have significant side effects and drug interactions.62,63 Nutraceuticals may contain multiple ingredients, some of which can be toxic, particularly at higher doses. Many patients may not volunteer information about their nutraceutical use to their health care providers,64 so we must ask them about that and inform them of the potential for adverse events and drug interactions.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects more than 2 million people in the United States each year.1 TBI can trigger a cascade of secondary injury mechanisms, such as inflammation, hypoxic/ischemic injury, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress,2 that could contribute to cognitive and behavioral changes. Although neuropsychiatric symptoms might not be obvious after a TBI, they have a high prevalence in these patients, can last long term, and may be difficult to treat.3 Despite research advances in understanding the biological basis of TBI and identifying potential therapeutic targets, treatment options for individuals with TBI remain limited.

As a result, clinicians have turned to alternative treatments for TBI, including nutraceuticals. In this article, we will:

- provide an overview of nutraceuticals used in treating TBI, first exploring outcomes soon after TBI, then concentrating on neuropsychiatric outcomes

- evaluate the existing evidence, including recommended dietary allowances (Table 1)4,5 and side effects (Table 2)

- review recommendations for their clinical use.

Pharmacologic approaches are limited

Nutraceuticals have gained attention for managing TBI-associated neuropsychiatric disorders because of the limited evidence supporting current approaches. Existing strategies encompass pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic interventions, psychoeducation, supportive and behavioral psychotherapies, and cognitive rehabilitation.6

Many pharmacologic options exist for specific neurobehavioral symptoms, but the evidence for their use is based on small studies, case reports, and knowledge extrapolated from their use in idiopathic psychiatric disorders.7,8 No FDA-approved drugs have been effective for treating neuropsychiatric disturbances after a TBI. Off-label use of antidepressants, anticonvulsants, dopaminergic agents, and cholinesterase inhibitors in TBI has been associated with inadequate clinical response and/or intolerable side effects.9,10

What are nutraceuticals?

DeFelice11 introduced the term “nutraceutical” to refer to “any substance that is a food or part of a food and provides medical or health benefits, including the prevention and treatment of disease.” The term has been expanded to include dietary supplements, such as vitamins, minerals, amino acids, herbal or other botanicals, and food products that provide health benefits beyond what they normally provide in food form. The FDA does not regulate the marketing or manufacturing of nutraceuticals; therefore, their bioavailability and metabolism can vary.

Despite their widespread use, the evidence supporting the efficacy of nutraceuticals for patients with TBI is limited. Their effects might vary by population and depend on dose, timing, TBI severity, and whether taken alone or in combination with other nutraceutical or pharmaceutical agents. Fourteen randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have addressed the use of nutraceuticals in TBI (Table 3), but further research is needed to clarify for which conditions they provide maximum benefit.

Nutraceuticals and their potential use in TBI

Zinc is considered essential for optimal CNS functioning. Patients with TBI might be at risk for zinc deficiency, which has been associated with increased cell death and behavioral deficits.12,13 A randomized, prospective, double-blinded controlled trial examined the effects of supplemental zinc administration (12 mg for 15 days) compared with standard zinc therapy (2.5 mg for 15 days) over 1 month in 68 adults with acute severe closed head injury.14 The supplemental zinc group showed improved visceral protein levels, lower mortality, and more favorable neurologic recovery based on higher adjusted mean Glasgow Coma Scale score on day 28 and mean motor score on days 15 and 21.

Rodent studies have shown that zinc supplementation could reduce deficits in spatial learning and memory and depression-like behaviors and help decrease stress and anxiety,12 although no human clinical trials have been conducted. Despite the potential neuroprotective effects of zinc supplementation, evidence exists that endogenous zinc release and accumulation following TBI can trigger cellular changes that result in neuronal death.13

Vitamins C and E. Oxidative damage is believed to play a significant role in secondary injury in TBI, so research has focused on the role of antioxidants, such as vitamins C and E, to promote post-TBI recovery.15 One RCT16 of 100 adults with acute severe head injury reported that vitamin E administration was associated with reduced mortality and lower Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS) scores, and vitamin C was associated with stabilized or reduced perilesional edema/infarct on CT scan.

Vitamin D. An animal study reported that vitamin D supplementation can help reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and cell death in TBI, and that vitamin D deficiency has been associated with increased inflammation and behavioral deficits.17 Further evidence suggests that vitamin D may have a synergistic effect when used in combination with the hormone progesterone. A RCT of 60 patients with severe TBI reported that 60% of those who received progesterone plus vitamin D had GOS scores of 4 (good recovery) or 5 (moderate disability) vs 45% receiving progesterone alone or 25% receiving placebo.18

Magnesium, one of the most widely used nutraceuticals, is considered essential for CNS functioning, including the regulation of N-methyl-

A RCT evaluated the safety and efficacy of magnesium supplementation in 60 patients with severe closed TBI, with one-half randomized to standard care and the other also receiving magnesium sulfate (MgSO4; initiation dose of 4 g IV and 10 g IM, continuation dose of 5 g IM every 4 hours for 24 hours).20 After 3 months, more patients in the MgSO4 group had higher GOS scores than controls (73.3% vs 40%), lower 1-month mortality rates (13.3% vs 43.3%), and lower rates of intraoperative brain swelling (29.4% vs 73.3%).

However, a larger RCT of 499 patients with moderate or severe TBI randomized to high-dose (1.25 to 2.5 mmol/L) or low-dose (1.0 to 1.85 mmol/L) IV MgSO4 or placebo provided conflicting results.21 Participants received MgSO4 8 hours after injury and continued for 5 days. After 6 months, patients in the high-dose MgSO4 and placebo groups had similar composite primary outcome measures (eg, seizures, neuropsychological measures, functional status measures), although the high-dose group had a higher mortality rate than the placebo group. Patients who received low-dose MgSO4 showed worse outcomes than those assigned to placebo.

Amino acids. Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), including valine, isoleucine, and leucine, are essential in protein and neurotransmitter synthesis. Reduced levels of endogenous BCAAs have been reported in patients with mild or severe TBI.22 Preclinical studies suggest that BCAAs can improve hippocampal-dependent cognitive functioning following TBI.23

Two RCTs of BCAAs have been conducted in humans. One study randomized 40 men with severe TBI to IV BCAAs or placebo.24 After 15 days, the BCAA group showed greater improvement in Disability Rating Scale scores. The study also found that supplementation increased total BCAA levels without negatively affecting plasma levels of neurotransmitter precursors tyrosine and tryptophan. A second study found that 41 patients in a vegetative or minimally conscious state who received BCAA supplementation for 15 days had higher Disability Rating Scale scores than those receiving placebo.25

Probiotics and glutamine. Probiotics are non-pathogenic microorganisms that have been shown to modulate the host’s immune system.26 TBI is associated with immunological changes, including a shift from T-helper type 1 (TH1) cells to T-helper type 2 (TH2) cells that increase susceptibility to infection.27

A RCT of 52 patients with severe TBI suggested a correlation between probiotic administration-modulated cytokine levels and TH1/TH2 balance.28 A 3-times daily probiotic mix of Bifidobacterium longum, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Streptococcus thermophilus for 21 days led to shorter average ICU stays (6.8 vs 10.7 days, P = .034) and a decrease in nosocomial infections (34.6% vs 57.7%, P = .095) vs placebo, although the latter difference was not statistically significant.28

A prospective RCT of 20 patients with brain injury29 found a similar impact of early enteral nutrition supplemented with Lactobacillus johnsonii and glutamine, 30 g, vs a standard enteral nutrition formula. The treatment group experienced fewer nosocomial infections (50% vs 100%, P = .03), shorter ICU stays (10 vs 22 days, P < .01), and fewer days on mechanical ventilation (7 vs 14, P = .04). Despite these studies, evidence for the use of glutamine in patients with TBI is scarce and inconclusive.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) comes from the amino acid L-cysteine. NAC is an effective scavenger of free radicals and improves cerebral microcirculatory blood flow and tissue oxygenation.30 A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of oral NAC supplementation in 81 active duty service members with mild TBI found NAC had a significant effect on outcomes.31 Oral NAC supplementation led to improved neuropsychological test results, number of mild TBI symptoms, complete symptom resolution by day 7 of treatment compared with placebo, and NAC was well tolerated. Lack of replication studies and generalizability of findings to civilian, moderate, or chronic TBI populations are key limitations of this study.

Proposed mechanisms for the neuroprotective benefit of NAC include its antioxidant and inflammatory activation of cysteine/glutamate exchange, metabotropic glutamate receptor modulation, and glutathione synthesis.32 NAC has poor blood–brain permeability, but the vascular disruption seen in acute TBI might facilitate its delivery to affected neural sites.31 As such, the benefits of NAC in subacute or chronic TBI are questionable.

Neuropsychiatric outcomes of nutraceuticals

Enzogenol. This flavonoid-rich extract from the bark of the Monterey pine tree (Pinus radiata), known by the trade name Enzogenol, reportedly has antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties that may counter oxidative damage and neuroinflammation following TBI. A phase II trial randomized participants to Enzogenol, 1,000 mg/d, or placebo for 6 weeks, then all participants received Enzogenol for 6 weeks followed by placebo for 4 weeks.33 Enzogenol was well tolerated with few side effects.

Compared with placebo, participants receiving Enzogenol showed no significant change in mood, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, and greater improvement in overall cognition as assessed by the Cognitive Failures Questionnaire. However, measures of working memory (digit span, arithmetic, and letter–number sequencing subtests of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale) and episodic memory (California Verbal Learning Test) showed no benefit from Enzogenol.

Citicoline (CDP-choline) is an endogenous compound widely available as a nutraceutical that has been approved for TBI therapy in 59 countries.34 Animal studies indicate that it could possess neuroprotective properties. Proposed mechanisms for such effects have included stabilizing cell membranes, reducing inflammation, reducing the presence of free radicals, or stimulating production of acetylcholine.35,36 A study in rats found that CDP-choline was associated with increased levels of acetylcholine in the hippocampus and neocortex, which may help reduce neurobehavioral deficits.37

A study of 14 adults with mild to moderate closed head injury38 found that patients who received CDP-choline showed a greater reduction in post-concussion symptoms and improvement in recognition memory than controls who received placebo. However, the Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial, a large randomized trial of 1,213 adults with complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI, reported that CDP-choline did not improve functional and cognitive status.39

Physostigmine and lecithin. The cholinergic system is a key modulatory neurotransmitter system of the brain that mediates conscious awareness, attention, learning, and working memory.40 A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 16 patients with moderate to severe closed head injury provided inconsistent evidence for the efficacy of physostigmine and lecithin in the treatment of memory and attention disturbances.41The results showed no differences between the physostigmine–lecithin combination vs lecithin alone, although sustained attention on the Continuous Performance Test was more efficient with physostigmine than placebo when the drug condition occurred first in the crossover design. The lack of encouraging data and concerns about its cardiovascular and proconvulsant properties in patients with TBI may explain the dearth of studies with physostigmine.

Cerebrolysin. A peptide preparation produced from purified pig brain proteins, known by the trade name Cerebrolysin, is popular in Asia and Europe for its nootropic properties. Cerebrolysin may activate cerebral mechanisms related to attention and memory processes,42 and some data have shown efficacy in improving cognitive symptoms and daily activities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease43 and TBI.44

A blinded 12-week study of 32 participants with acute mild TBI reported that those randomized to Cerebrolysin showed improvement in cognitive functioning vs the placebo group.45 The authors concluded that Cerebrolysin provides an advantage for patients with mild TBI and brain contusion if treatment starts within 24 hours of mild TBI onset. Cerebrolysin was well tolerated. Major limitations of this study were small sample size, lack of information regarding comorbid neuropsychiatric conditions and treatments, and short treatment duration.

A recent Cochrane review of 6 RCTs with 1,501 participants found no clinical benefit of Cerebrolysin for treating acute ischemic stroke, and found moderate-quality evidence of an increase with non-fatal serious adverse events but not in total serious adverse events.46 We do not recommend Cerebrolysin use in patients with TBI at this time until additional efficacy and safety data are available.

Nutraceuticals used in other populations

Other nutraceuticals with preclinical evidence of possible benefit in TBI but lacking evidence from human clinical trials include omega-3 fatty acids,47 curcumin,48 and resveratrol,49 providing further proof that results from experimental studies do not necessarily extend to clinical trials.50

Studies of nutraceuticals in other neurological and psychiatric populations have yielded some promising results. Significant interest has focused on the association between vitamin D deficiency, dementia, and neurodegenerative conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson’s disease.51 The role of vitamin D in regulation of calcium-mediated neuronal excitotoxicity and oxidative stress and in the induction of synaptic structural proteins, neurotrophic factors, and deficient neurotransmitters makes it an attractive candidate as a neuroprotective agent.52

RCTs of nutraceuticals also have reported positive findings for a variety of mood and anxiety disorders, such as St. John’s wort, S-adenosylmethionine, omega-3 fatty acids for major depression53 and bipolar depression,54 and kava for generalized anxiety disorder.55 More research, however, is needed in these areas.

The use of nonpharmacologic agents in TBI often relies on similar neuropsychiatric symptom profiles of idiopathic psychiatric disorders. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) closely resembles TBI, but systemic reviews of studies of zinc, magnesium, and polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation in ADHD provide no evidence of therapeutic benefit.56-58

Educate patients in role of nutraceuticals

Despite lack of FDA oversight and limited empirical support, nutraceuticals continue to be widely marketed and used for their putative health benefits59 and have gained increased attention among clinicians.60 Because nutritional deficiency may make the brain less able than other organs to recover from injury,61 supplementation is an option, especially in individuals who could be at greater risk of TBI (eg, athletes and military personnel).

Lacking robust scientific evidence to support the use of nutraceuticals either for enhancing TBI recovery or treating neuropsychiatric disturbances, clinicians must educate patients that these agents are not completely benign and can have significant side effects and drug interactions.62,63 Nutraceuticals may contain multiple ingredients, some of which can be toxic, particularly at higher doses. Many patients may not volunteer information about their nutraceutical use to their health care providers,64 so we must ask them about that and inform them of the potential for adverse events and drug interactions.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pubs/congress_epi_rehab.html. Updated January 22, 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(1):4-9.

3. Vaishnavi S, Rao V, Fann JR. Neuropsychiatric problems after traumatic brain injury: unraveling the silent epidemic. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):198-205.

4. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all. Accessed June 5, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2002.

6. Rao V, Koliatsos V, Ahmed F, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with traumatic brain injury: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(1):64-82.

7. Chew E, Zafonte RD. Pharmacological management of neurobehavioral disorders following traumatic brain injury—a state-of-the-art review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):851-879.

8. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533; discussion 1533.

9. Bengtsson M, Godbolt AK. Effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on cognitive function in patients with chronic traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(1):1-5.

10. Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working Group; Warden DL, Gordon B, McAllister TW, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1468-1501.

11. DeFelice SL. The nutraceutical revolution: its impact on food industry R&D. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1995;6(2):59-61.

12. Cope EC, Morris DR, Levenson CW. Improving treatments and outcomes: an emerging role for zinc in traumatic brain injury. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(7):410-413.

13. Morris DR, Levenson CW. Zinc in traumatic brain injury: from neuroprotection to neurotoxicity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(6):708-711.

14. Young B, Ott L, Kasarskis E, et al. Zinc supplementation is associated with improved neurologic recovery rate and visceral protein levels of patients with severe closed head injury. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13(1):25-34.

15. Fernández-Gajardo R, Matamala JM, Carrasco R, et al. Novel therapeutic strategies for traumatic brain injury: acute antioxidant reinforcement. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(3):229-248.

16. Razmkon A, Sadidi A, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh E, et al. Administration of vitamin C and vitamin E in severe head injury: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin Neurosurg. 2011;58:133-137.

17. Cekic M, Cutler SM, VanLandingham JW, et al. Vitamin D deficiency reduces the benefits of progesterone treatment after brain injury in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(5):864-874.

18. Aminmansour B, Nikbakht H, Ghorbani A, et al. Comparison of the administration of progesterone versus progesterone and vitamin D in improvement of outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trial with placebo group. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:58.

19. Cernak I, Savic VJ, Kotur J, et al. Characterization of plasma magnesium concentration and oxidative stress following graded traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(1):53-68.

20. Dhandapani SS, Gupta A, Vivekanandhan S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of magnesium sulphate in severe closed traumatic brain injury. The Indian Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008;5(1):27-33.

21. Temkin NR, Anderson GD, Winn HR, et al. Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection after traumatic brain injury: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(1):29-38.

22. Jeter CB, Hergenroeder GW, Ward NH 3rd, et al. Human mild traumatic brain injury decreases circulating branched-chain amino acids and their metabolite levels. J Neurotrauma. 2013;30(8):671-679.

23. Cole JT, Mitala CM, Kundu S, et al. Dietary branched chain amino acids ameliorate injury-induced cognitive impairment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(1):366-371.

24. Aquilani R, Iadarola P, Contardi A, et al. Branched-chain amino acids enhance the cognitive recovery of patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2005;86(9):1729-1735.

25. Aquilani R, Boselli M, Boschi F, et al. Branched-chain amino acids may improve recovery from a vegetative or minimally conscious state in patients with traumatic brain injury: a pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2008;89(9):1642-1647.

26. Kang HJ, Im SH. Probiotics as an immune modulator. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2015;61(suppl):S103-S105.

27. DiPiro JT, Howdieshell TR, Goddard JK, et al. Association of interleukin-4 plasma levels with traumatic injury and clinical course. Arch Surg. 1995;130(11):1159-1162; discussion 1162-1163.

28. Tan M, Zhu JC, Du J, et al. Effects of probiotics on serum levels of Th1/Th2 cytokine and clinical outcomes in severe traumatic brain-injured patients: a prospective randomized pilot study. Crit Care. 2011;15(6):R290.

29. Falcão de Arruda IS, de Aguilar-Nascimento JE. Benefits of early enteral nutrition with glutamine and probiotics in brain injury patients. Clin Sci (Lond). 2004;106(3):287-292.

30. Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Costantino G, et al. Beneficial effects of n-acetylcysteine on ischaemic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. 2000;130(6):1219-1226.

31. Hoffer ME, Balaban C, Slade MD, et al. Amelioration of acute sequelae of blast induced mild traumatic brain injury by N-acetyl cysteine: a double-blind, placebo controlled study. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54163.

32. Eakin K, Baratz-Goldstein R, Pick CG, et al. Efficacy of N-acetyl cysteine in traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e90617.

33. Theadom A, Mahon S, Barker-Collo S, et al. Enzogenol for cognitive functioning in traumatic brain injury: a pilot placebo-controlled RCT. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20(8):1135-1144.

34. Arenth PM, Russell KC, Ricker JH, et al. CDP-choline as a biological supplement during neurorecovery: a focused review. PM R. 2011;3(6 suppl 1):S123-S131.

35. Clark WM. Efficacy of citicoline as an acute stroke treatment. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2009;10(5):839-846.

36. Guseva MV, Hopkins DM, Scheff SW, et al. Dietary choline supplementation improves behavioral, histological, and neurochemical outcomes in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2008;25(8):975-983.

37. Dixon CE, Ma X, Marion DW. Effects of CDP-choline treatment on neurobehavioral deficits after TBI and on hippocampal and neocortical acetylcholine release. J Neurotrauma. 1997;14(3):161-169.

38. Levin HS. Treatment of postconcussional symptoms with CDP-choline. J Neurol Sci. 1991;103(suppl):S39-S42.

39. Zafonte RD, Bagiella E, Ansel BM, et al. Effect of citicoline on functional and cognitive status among patients with traumatic brain injury: Citicoline Brain Injury Treatment Trial (COBRIT). JAMA. 2012;308(19):1993-2000.

40. Perry E, Walker M, Grace J, et al. Acetylcholine in mind: a neurotransmitter correlate of consciousness? Trends Neurosci. 1999;22(6):273-280.

41. Levin HS, Peters BH, Kalisky Z, et al. Effects of oral physostigmine and lecithin on memory and attention in closed head-injured patients. Cent Nerv Syst Trauma. 1986;3(4):333-342.

42. Alvarez XA, Lombardi VR, Corzo L, et al. Oral cerebrolysin enhances brain alpha activity and improves cognitive performance in elderly control subjects. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:315-328.

43. Ruether E, Husmann R, Kinzler E, et al. A 28-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with cerebrolysin in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer’s disease. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(5):253-263.

44. Wong GK, Zhu XL, Poon WS. Beneficial effect of cerebrolysin on moderate and severe head injury patients: result of a cohort study. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2005;95:59-60.

45. Chen CC, Wei ST, Tsaia SC, et al. Cerebrolysin enhances cognitive recovery of mild traumatic brain injury patients: double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized study. Br J Neurosurg. 2013;27(6):803-807.

46. Ziganshina LE, Abakumova T, Vernay L. Cerebrolysin for acute ischaemic stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;12:CD007026.

47. Barrett EC, McBurney MI, Ciappio ED. ω-3 fatty acid supplementation as a potential therapeutic aid for the recovery from mild traumatic brain injury/concussion. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(3):268-277.

48. Sharma S, Zhuang Y, Ying Z, et al. Dietary curcumin supplementation counteracts reduction in levels of molecules involved in energy homeostasis after brain trauma. Neuroscience. 2009;161(4):1037-1044.

49. Gatson JW, Liu MM, Abdelfattah K, et al. Resveratrol decreases inflammation in the brain of mice with mild traumatic brain injury. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74(2):470-475; discussion 474-475.

50. Grey A, Bolland M. Clinical trial evidence and use of fish oil supplements. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):460-462.

51. Mpandzou G, Aït Ben Haddou E, Regragui W, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and its role in neurological conditions: a review. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2016;172(2):109-122.

52. Karakis I, Pase MP, Beiser A, et al. Association of serum vitamin D with the risk of incident dementia and subclinical indices of brain aging: The Framingham Heart Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;51(2):451-461.

53. Sarris J, Papakostas GI, Vitolo O, et al. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) versus escitalopram and placebo in major depression RCT: efficacy and effects of histamine and carnitine as moderators of response. J Affect Disord. 2014;164:76-81.

54. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

55. Sarris J, Stough C, Bousman C, et al. Kava in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(5):643-648.

56. Hariri M, Azadbakht L. Magnesium, iron, and zinc supplementation for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review on the recent literature. Int J Prev Med. 2015;6:83.

57. Gillies D, Sinn JKh, Lad SS, et al. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;7:CD007986.

58. Ghanizadeh A, Berk M. Zinc for treating of children and adolescents with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review of randomized controlled clinical trials. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2013;67(1):122-124.

59. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Can a dietary supplement treat a concussion? No! http://www.fda.gov/forconsumers/consumerupdates/ucm378845.htm. Updated February 13, 2015. Accessed June 5, 2017.

60. Sarris J, Logan AC, Akbaraly TN, et al; International Society for Nutritional Psychiatry Research. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(3):271-274.

61. Desai A, Kevala K, Kim HY. Depletion of brain docosahexaenoic acid impairs recovery from traumatic brain injury. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e86472.

62. Edie CF, Dewan N. Which psychotropics interact with four common supplements. Current Psychiatry. 2005;4(1):16-30.

63. Di Lorenzo C, Ceschi A, Kupferschmidt H, et al. Adverse effects of plant food supplements and botanical preparations: a systematic review with critical evaluation of causality. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(4):578-592.

64. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary and alternative medicine: what people aged 50 and older discuss with their health care providers. https://nccih.nih.gov/research/statistics/2010. Published 2011. Accessed June 5, 2017.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report to Congress on traumatic brain injury in the United States: epidemiology and rehabilitation. https://www.cdc.gov/traumaticbraininjury/pubs/congress_epi_rehab.html. Updated January 22, 2016. Accessed June 5, 2017.

2. Werner C, Engelhard K. Pathophysiology of traumatic brain injury. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(1):4-9.

3. Vaishnavi S, Rao V, Fann JR. Neuropsychiatric problems after traumatic brain injury: unraveling the silent epidemic. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(3):198-205.

4. National Institutes of Health Office of Dietary Supplements. Dietary supplement fact sheets. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/list-all. Accessed June 5, 2017.

5. Institute of Medicine, Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary reference intakes for energy, carbohydrate, fiber, fat, fatty acids, cholesterol, protein, and amino acids. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences; 2002.

6. Rao V, Koliatsos V, Ahmed F, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbances associated with traumatic brain injury: a practical approach to evaluation and management. Semin Neurol. 2015;35(1):64-82.

7. Chew E, Zafonte RD. Pharmacological management of neurobehavioral disorders following traumatic brain injury—a state-of-the-art review. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2009;46(6):851-879.

8. Petraglia AL, Maroon JC, Bailes JE. From the field of play to the field of combat: a review of the pharmacological management of concussion. Neurosurgery. 2012;70(6):1520-1533; discussion 1533.

9. Bengtsson M, Godbolt AK. Effects of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors on cognitive function in patients with chronic traumatic brain injury: a systematic review. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48(1):1-5.

10. Neurobehavioral Guidelines Working Group; Warden DL, Gordon B, McAllister TW, et al. Guidelines for the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral sequelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;23(10):1468-1501.

11. DeFelice SL. The nutraceutical revolution: its impact on food industry R&D. Trends Food Sci Technol. 1995;6(2):59-61.

12. Cope EC, Morris DR, Levenson CW. Improving treatments and outcomes: an emerging role for zinc in traumatic brain injury. Nutr Rev. 2012;70(7):410-413.

13. Morris DR, Levenson CW. Zinc in traumatic brain injury: from neuroprotection to neurotoxicity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2013;16(6):708-711.

14. Young B, Ott L, Kasarskis E, et al. Zinc supplementation is associated with improved neurologic recovery rate and visceral protein levels of patients with severe closed head injury. J Neurotrauma. 1996;13(1):25-34.

15. Fernández-Gajardo R, Matamala JM, Carrasco R, et al. Novel therapeutic strategies for traumatic brain injury: acute antioxidant reinforcement. CNS Drugs. 2014;28(3):229-248.

16. Razmkon A, Sadidi A, Sherafat-Kazemzadeh E, et al. Administration of vitamin C and vitamin E in severe head injury: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin Neurosurg. 2011;58:133-137.

17. Cekic M, Cutler SM, VanLandingham JW, et al. Vitamin D deficiency reduces the benefits of progesterone treatment after brain injury in aged rats. Neurobiol Aging. 2011;32(5):864-874.

18. Aminmansour B, Nikbakht H, Ghorbani A, et al. Comparison of the administration of progesterone versus progesterone and vitamin D in improvement of outcomes in patients with traumatic brain injury: a randomized clinical trial with placebo group. Adv Biomed Res. 2012;1:58.

19. Cernak I, Savic VJ, Kotur J, et al. Characterization of plasma magnesium concentration and oxidative stress following graded traumatic brain injury in humans. J Neurotrauma. 2000;17(1):53-68.

20. Dhandapani SS, Gupta A, Vivekanandhan S, et al. Randomized controlled trial of magnesium sulphate in severe closed traumatic brain injury. The Indian Journal of Neurotrauma. 2008;5(1):27-33.