User login

Medical Communities Go Virtual

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

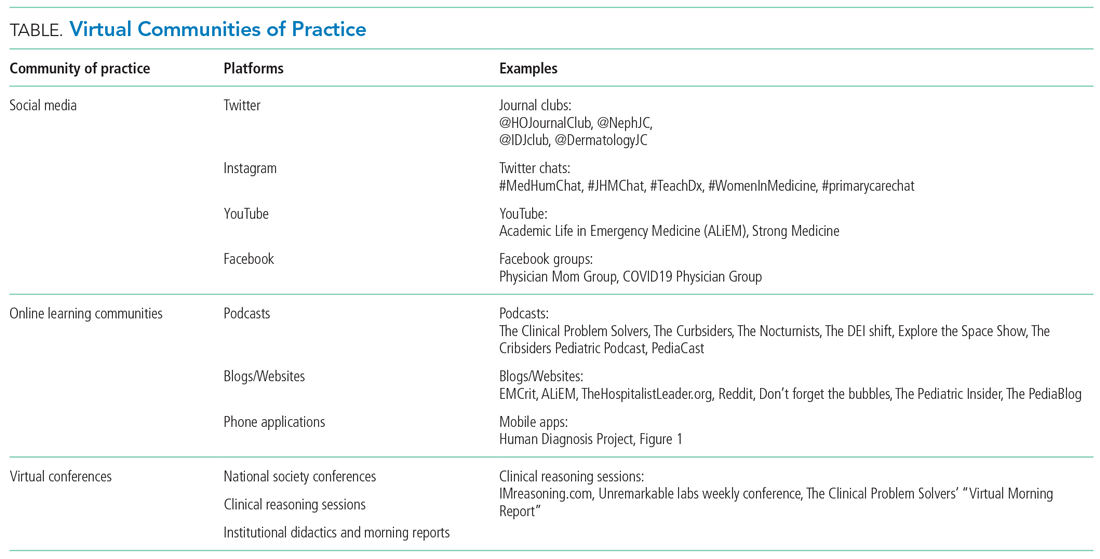

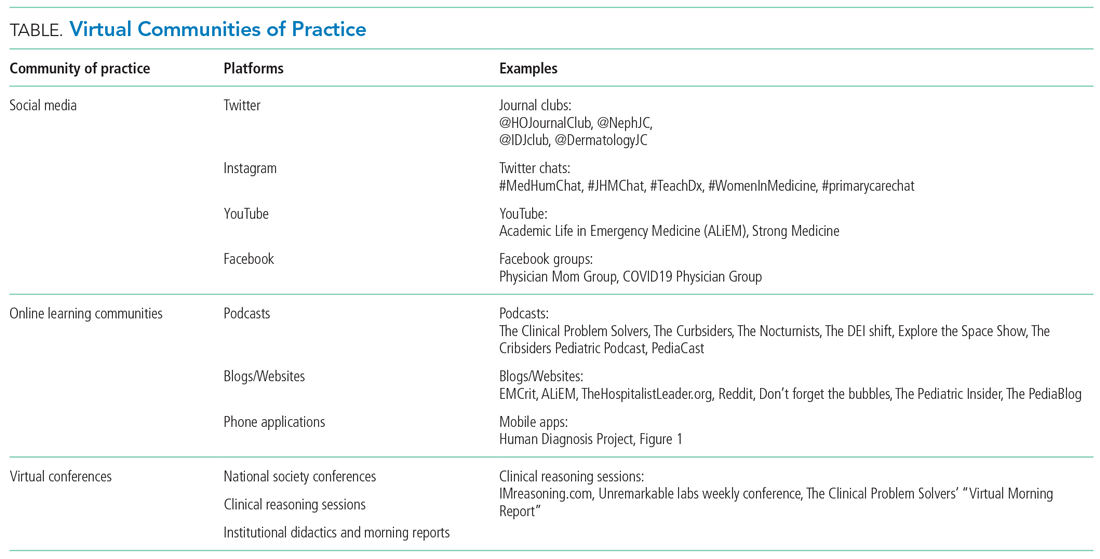

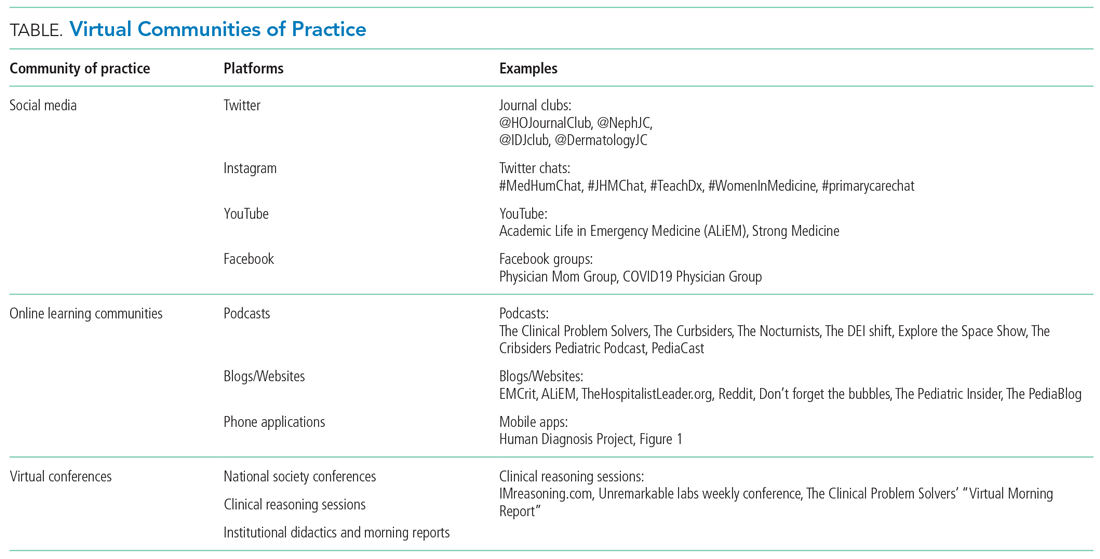

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

Throughout history, physicians have formed communities to aid in the dissemination of knowledge, skills, and professional norms. From local physician groups to international societies and conferences, this drive to connect with members of our profession across the globe is timeless. We do so to learn from each other and continue to move the field of medicine forward.

Yet, these communities are being strained by necessary physical distancing required during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many physicians accustomed to a sense of community are now finding themselves surprisingly isolated and alone. Into this distanced landscape, however, new digital groups—specifically social media (SoMe), online learning communities, and virtual conferences—have emerged. We are all active members in virtual communities; all of the authors are team members of The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast and one author of this paper, A.P., has previously served as the medical education lead for the Human Diagnosis Project. Both entities are described later in this article. Here, we provide an overview of these virtual communities and discuss how they have the potential to more equitably and effectively disseminate medical knowledge and education both during and after the COVID-19 pandemic (Table).

SOCIAL MEDIA

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, SoMe—especially Twitter—had become a virtual gathering place where digital colleagues exchange Twitter handles like business cards.1,2 They celebrate each other’s achievements and provide support during difficult times.

Importantly, the format of Twitter tends toward a flattened hierarchy. It is this egalitarian nature that has served SoMe well in its position as a modern learning community. Users from across the experience spectrum engage with and create novel educational content. This often occurs in the form of Tweetorials, or short lessons conveyed over a series of linked tweets. These have gained immense popularity on the platform and are becoming increasingly recognized forms of scholarship.3 Further, case-based lessons have become ubiquitous and are valuable opportunities for users to learn from other members of their digital communities. During the current pandemic, SoMe has become extremely important in the early dissemination and critique of the slew of research on the COVID-19 crisis.4

Beyond its role as an educational platform, SoMe functions as a virtual gathering place for members of the medical community to discuss topics relevant to the field. Subspecialists and researchers have gathered in digital journal clubs (eg, #NephJC, #IDJClub, #BloodandBone) and a number of journals have hosted live Twitter chats covering topics like controversies in clinical practice or professional development (eg, #JHMChat). More recently, social issues affecting the medical field, such as gender equity and the growing antiracism movement, have led to robust discussion on this medium.

Beyond Twitter, many medical professionals gather and exchange ideas on other platforms. Virtual networking and educational groups have arisen using Slack and Facebook.5-7 Trainees and faculty members alike consume and produce content on YouTube, which often serve to teach technical skills.8 Given widespread use of SoMe, we anticipate that the range of platforms utilized by medical professionals will continue to expand in the future.

ONLINE LEARNING COMMUNITIES

There have long existed multiple print and online forums dedicated to the development of clinical skills. These include clinical challenges in medical journals, interactive online cases, and more formal diagnostic education curricula at academic centers.9-11 With the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become more difficult to ensure that trainees have an in-person learning community to discuss and receive feedback. This has led to a wider adoption of application-based clinical exercises, educational podcasts, and curricular innovations to support these virtual efforts.

The Human Diagnosis Project (Human Dx) is a smart-phone application that provides a platform for individuals to submit clinical cases that can be rapidly peer-reviewed and disseminated to the larger user pool. Human Dx is notable for fostering a strong sense of community amongst its users.12,13 Case consumers and case creators are able to engage in further discussion after solving a case, and opportunities for feedback and growth are ample.

Medical education podcasts have taken on greater importance during the pandemic.14,15 Many educators have begun referring their learners towards certain podcasts as in-person learning communities have been put on hold. Medical professionals may appreciate the up-to-date and candid conversations held on many podcasts, which can provide both educationally useful and emotionally sympathetic connections to their distanced peers. Similarly, while academic clinicians previously benefitted from invited grand rounds speakers, they may now find that such expert discussants are most easily accessible through their appearances on podcasts.

As institutions suspended clerkships during the pandemic, many created virtual communities for trainees to engage in diagnostic reasoning and education. They built novel curricula that meld asynchronous learning with online community-based learning.14 Gamified learning tools and quizzes have also been incorporated into these hybrid curricula to help ensure participation of learners within their virtual communities.16,17

VIRTUAL CONFERENCES

Perhaps the most notable advance in digital communities catalyzed by the COVID-19 pandemic has been the increasing reliance on and comfort with video-based software. While many of our clinical, administrative, and social activities have migrated toward these virtual environments, they have also been used for a variety of activities related to education and professional development.

As institutions struggled to adapt to physical distancing, many medical schools and residency programs have moved their regular meetings and conferences to virtual platforms. Similar free and open-access conferences have also emerged, including the “Virtual Morning Report” (VMR) series from The Clinical Problem Solvers podcast, wherein a few individuals are invited to discuss a case on the video conference, with the remainder of the audience contributing via the chat feature.

Beyond the growing popularity of video conferencing for education, these virtual sessions have become their own community. On The Clinical Problem Solvers VMR, many participants, ranging from preclinical students to seasoned attendings, show up on a daily basis and interact with each other as close friends, as do members of more insular institutional sessions (eg, residency run reports). In these strangely isolating times, many of us have experienced comfort in seeing the faces of our friends and colleagues joining us to listen and discuss cases.

Separately, many professional societies have struggled with how to replace their large yearly in-person conferences, which would pose substantial infectious risks were they to be held in person. While many of those scheduled to occur during the early days of the pandemic were canceled or held limited online sessions, the trend towards virtual conference platforms seems to be accelerating. Organizers of the 2020 Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (March 8-11, 2020) decided to convert from an in-person to entirely virtual conference 48 hours before it started. With the benefit of more forewarning, other conferences are planning and exploring best practices to promote networking and advancement of research goals at future academic meetings.18,19

BENEFITS OF VIRTUAL COMMUNITIES

The growing importance of these new digital communities could be viewed as a necessary evolution in the way that we gather and learn from each other. Traditional physician communities were inherently restricted by location, specialty, and hierarchy, thereby limiting the dissemination of knowledge and changes to professional norms. These restrictions could conceivably insulate and promote elite institutions in a fashion that perpetuates the inequalities within global medical systems. Unrestricted and open-access virtual communities, in contrast, have the potential to remove historical barriers and connect first-class mentors with trainees they would never have met otherwise.

Beyond promoting a more equitable distribution of knowledge and resources, these virtual communities are well suited to harness the benefits of group learning. The concept of communities of practice (CoP) refers to groupings of individuals involved in a personal or professional endeavor, with the community facilitating advancement of their own knowledge and skill set. Members of the CoP learn from each other, with more established members passing down essential knowledge and cultural norms. The three main components of CoP are maintaining a social network, a mutual enterprise (eg, a common goal), and a shared repertoire (eg, experiences, languages, etc).

Designing virtual learning spaces with these aspects in mind may allow these communities to function as CoPs. Some strategies include use of chat functions in videoconferences (to promote further dialogue) and development of dedicated sessions for specific subgroups or aims (eg, professional mentorship). The anticipated benefits of integrating virtual CoPs into medical education are notable, as a number of studies have already suggested that they are effective for disseminating knowledge, enhancing social learning, and aiding with professional development.7,20-23 These virtual CoPs continue to evolve, however, and further research is warranted to clarify how best to utilize them in medical education and professional societies.

CONCLUSION

Amidst the tragic loss of lives and financial calamity, the COVID-19 pandemic has also spurred innovation and change in the way health professionals learn and communicate. Going forward, the medical establishment should capitalize on these recent innovations and work to further build, recognize, and foster such digital gathering spaces in order to more equitably and effectively disseminate knowledge and educational resources.

Despite physical distancing, health professionals have grown closer during these past few months. Innovations spurred by the pandemic have made us stronger and more united. Our experience with social media, online learning communities, and virtual conferences suggests the opportunity to grow and evolve from this experience. As Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, said in March 2020, “...life is not going to be how it used to be [after the pandemic]…” Let’s hope he’s right.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Reza Manesh, MD, Rabih Geha, MD, and Jack Penner, MD, for their careful review of the manuscript.

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

1. Markham MJ, Gentile D, Graham DL. Social media for networking, professional development, and patient engagement. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:782-787. https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_180077

2. Melvin L, Chan T. Using Twitter in clinical education and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):581-582. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-14-00342.1

3. Breu AC. Why is a cow? Curiosity, Tweetorials, and the return to why. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(12):1097-1098. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906790

4. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020:10.1111/anae.15057. https://doi.org/10.1111/anae.15057

5. Pander T, Pinilla S, Dimitriadis K, Fischer MR. The use of Facebook in medical education--a literature review. GMS Z Med Ausbild. 2014;31(3):Doc33. https://doi.org/10.3205/zma000925

6. Cree-Green M, Carreau AM, Davis SM, et al. Peer mentoring for professional and personal growth in academic medicine. J Investig Med. 2020;68(6):1128-1134. https://doi.org/10.1136/jim-2020-001391

7. Yarris LM, Chan TM, Gottlieb M, Juve AM. Finding your people in the digital age: virtual communities of practice to promote education scholarship. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(1):1-5. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-01093.1

8. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92(7):1043-1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617

9. Manesh R, Dhaliwal G. Digital tools to enhance clinical reasoning. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(3):559-565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.015

10. Subramanian A, Connor DM, Berger G, et al. A curriculum for diagnostic reasoning: JGIM’s exercises in clinical reasoning. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(3):344-345. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4689-y

11. Olson APJ, Singhal G, Dhaliwal G. Diagnosis education - an emerging field. Diagnosis (Berl). 2019;6(2):75-77. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0029

12. Chatterjee S, Desai S, Manesh R, Sun J, Nundy S, Wright SM. Assessment of a simulated case-based measurement of physician diagnostic performance. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(1):e187006. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.7006

13. Russell SW, Desai SV, O’Rourke P, et al. The genealogy of teaching clinical reasoning and diagnostic skill: the GEL Study. Diagnosis (Berl). 2020;7(3):197-203. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2019-0107

14. Geha R, Dhaliwal G. Pilot virtual clerkship curriculum during the COVID-19 pandemic: podcasts, peers, and problem-solving. Med Educ. 2020;54(9):855-856. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14246

15. AlGaeed M, Grewal M, Richardson PK, Leon Guerrero CR. COVID-19: Neurology residents’ perspective. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;78:452-453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2020.05.032

16. Moro C, Stromberga Z. Enhancing variety through gamified, interactive learning experiences. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14251

17. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020. Online ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14253

18. Rubinger L, Gazendam A, Ekhtiari S, et al. Maximizing virtual meetings and conferences: a review of best practices. Int Orthop. 2020;44(8):1461-1466. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-020-04615-9

19. Woolston C. Learning to love virtual conferences in the coronavirus era. Nature. 2020;582(7810):135-136. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01489-0

20. Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Medicine as a community of practice: implications for medical education. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):185-191. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001826

21. McLoughlin C, Patel KD, O’Callaghan T, Reeves S. The use of virtual communities of practice to improve interprofessional collaboration and education: findings from an integrated review. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(2):136-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2017.1377692

22. Barnett S, Jones SC, Caton T, Iverson D, Bennett S, Robinson L. Implementing a virtual community of practice for family physician training: a mixed-methods case study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(3):e83. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3083

23. Healy MG, Traeger LN, Axelsson CGS, et al. NEJM Knowledge+ Question of the Week: a novel virtual learning community effectively utilizing an online discussion forum. Med Teach. 2019;41(11):1270-1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2019.1635685

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

More Is Less

A 64-year-old man presented with a 2-month history of a nonproductive cough, weight loss, and subjective fevers. He had no chest pain, hemoptysis, or shortness of breath. He also described worsening anorexia and a 15-pound weight loss over the previous 3 months. He had no arthralgias, myalgias, abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, or diarrhea.

Two weeks prior to his presentation, he was diagnosed with pneumonia and given a 5-day course of azithromycin. His symptoms did not improve, so he presented to the emergency room.

He had not been seen regularly by a physician in decades and had no known medical conditions. He did not take any medications. He immigrated from China 3 years prior and lived with his wife in California. He had a 30 pack-year smoking history. He drank a shot glass of liquor daily and denied any drug use.

Weight loss might result from inflammatory disorders like cancer or noninflammatory causes such as decreased oral intake (eg, diminished appetite) or malabsorption (eg, celiac disease). However, his fevers suggest inflammation, which usually reflects an underlying infection, cancer, or autoimmune process. While chronic cough typically results from upper airway cough syndrome (allergic or nonallergic rhinitis), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or asthma, it can also point to pathology of the lung, which may be intrinsic (bronchiectasis) or extrinsic (mediastinal mass). The duration of 2 months makes a typical infectious process like pneumococcal pneumonia unlikely. Atypical infections such as tuberculosis, melioidosis, and talaromycosis are possible given his immigration from East Asia, and coccidioidomycosis given his residence in California. He might have undiagnosed medical conditions, such as diabetes, that could be relevant to his current presentation and classify him as immunocompromised. His smoking history prompts consideration of lung cancer.

His temperature was 36.5 oC, heart rate 70 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/66 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 98% on room air, and body mass index 23 kg/m2. He was in no acute distress. The findings from the cardiac, lung, abdominal, and neurological exams were normal.

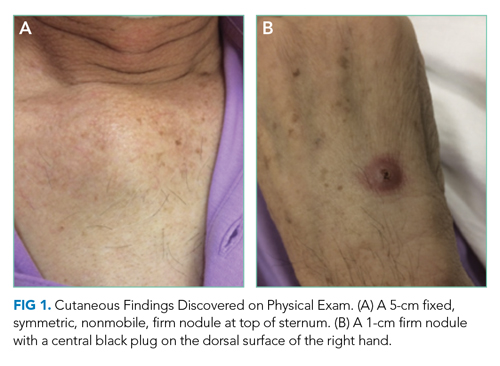

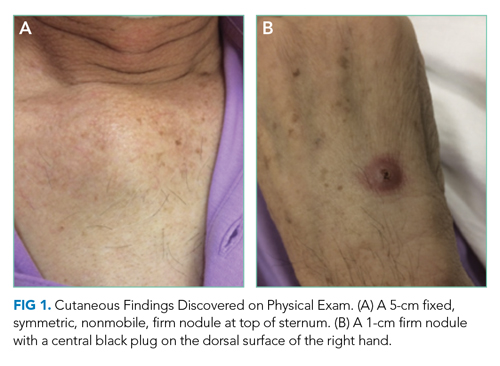

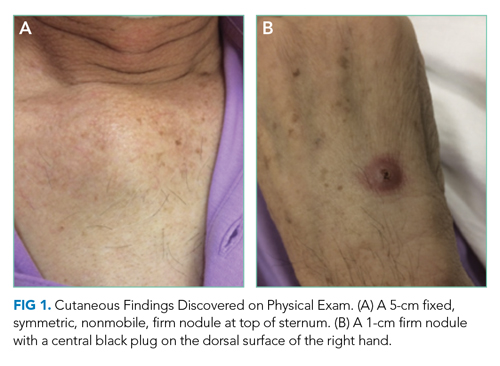

Skin examination found a fixed, symmetric, 5-cm, firm nodule at top of sternum (Figure 1A). In addition, he had two 1-cm, mobile, firm, subcutaneous nodules, one on his anterior left chest and another underneath his right axilla. He also had two 2-cm, erythematous, tender nodules on his left anterior forearm and a 1-cm nodule with a central black plug on the dorsal surface of his right hand (Figure 1B). He did not have any edema.

The white blood cell count was 10,500/mm3 (42% neutrophils, 37% lymphocytes, 16.4% monocytes, and 2.9% eosinophils), hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 91 fL, and the platelet count was 441,000/mm3. Basic metabolic panel, aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were within reference ranges. Serum albumin was 3.1 g/dL. Serum total protein was elevated at 8.8 g/dL. Serum calcium was 9.0 mg/dL. Urinalysis results were normal.

The slightly low albumin, mildly elevated platelet count, monocytosis, and normocytic anemia suggest inflammation, although monocytosis might represent a hematologic malignancy like chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). His subjective fevers and weight loss further corroborate underlying inflammation. What is driving the inflammation? There are two localizing findings: cough and nodular skin lesions.

His lack of dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and lung exam make an extrapulmonary cause of cough such as lymphadenopathy or mediastinal infection possible. The number of nodular skin lesions, wide-spread distribution, and appearance (eg, erythematous, tender) point to either a primary cutaneous disease with systemic manifestations (eg, cutaneous lymphoma) or a systemic disease with cutaneous features (eg, sarcoidosis).

Three categories—inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic—account for most nodular skin lesions. Usually microscopic evaluation is necessary for definitive diagnosis, though epidemiology, associated symptoms, and characteristics of the nodules help prioritize the differential diagnosis. Tender nodules might reflect a panniculitis; erythema nodosum is the most common type, and while this classically develops on the anterior shins, it may also occur on the forearm. His immigration from China prompts consideration of tuberculosis and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Coccidioidomycosis can lead to inflammation and nodular skin lesions. Other infections such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, nocardiosis, and cryptococcosis may cause disseminated infection with pulmonary and skin manifestations. His smoking puts him at risk of lung cancer, which rarely results in metastatic subcutaneous infiltrates.

A chest radiograph demonstrated a prominent density in the right paratracheal region of the mediastinum with adjacent streaky opacities. A computed tomography scan of the chest with intravenous contrast demonstrated centrilobular emphysematous changes and revealed a 2.6 × 4.7-cm necrotic mass in the anterior chest wall with erosion into the manubrium, a 3.8 × 2.1-cm centrally necrotic soft-tissue mass in the right hilum, a 5-mm left upper-lobe noncalcified solid pulmonary nodule, and prominent subcarinal, paratracheal, hilar, and bilateral supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (Figure 2).

Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood did not demonstrate a lymphoproliferative disorder. Blood smear demonstrated normal red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet morphology. HIV antibody was negative. Hemoglobin A1c was 6.1%. Smear microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) was negative and sputum AFB samples were sent for culture. Bacterial, fungal, and AFB blood cultures were collected and pending.

Causes of necrotizing pneumonia include liquid (eg, lymphoma) and solid (eg, squamous cell carcinoma) cancers, infections, and noninfectious inflammatory processes such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Given his subacute presentation and extrapulmonary cutaneous manifestations, consideration of mycobacteria, fungi (eg, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, and Cryptococcus), and filamentous bacteria (eg, Nocardia and Actinomyces) is prioritized among the myriad of infections that can cause a lung cavity. His smoking history and centrilobular emphysematous changes are highly suggestive of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which puts him at increased risk of bacterial colonization and recurrent pulmonary infections. Tuberculosis is still possible despite three negative AFB-sputa smears given the sensitivity of smear microscopy (with three specimens) is roughly 70% in an immunocompetent host.

The lymphadenopathy likely reflects spread from the necrotic lung mass. The frequency of non-Hodgkin lymphoma increases with age. The results of the peripheral flow cytometry do not exclude the possibility of an aggressive lymphoma with pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations.

The erosive property of the chest wall mass makes an autoimmune process like GPA unlikely. An aggressive and disseminated infection or cancer is most likely. A pathologic process that originated in the lung and then spread to the lymph nodes and skin is more likely than a disorder which started in the skin. It would be unlikely for a primary cutaneous disorder to cause such a well-defined necrotic lung mass. Lung cancer rarely metastasizes to the skin and, instead, preferentially involves the chest. Ultimately, ascertaining what the patient experienced first (ie, respiratory or cutaneous symptoms) will determine where the pathology originated.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated multiple ill-defined lytic lesions in the pelvis, including a 12-mm lesion of the left sacral ala and multiple subcentimeter lesions in the medial left iliac bone and superior right acetabulum. In addition, there were two 1-cm, rim-enhancing, hypodense nodules in the subcutaneous fat of the right flank at the level of L5 and the left lower quadrant, respectively. There was also a 2.2 × 1.9-cm faintly rim-enhancing hypodensity within the left iliopsoas muscle belly.

These imaging findings further corroborate a widely metastatic process probably originating in the lung and spreading to the lymph nodes, skin, muscles, and bones. The characterization of lesions as lytic as opposed to blastic is less helpful because many diseases can cause both. It does prompt consideration of multiple myeloma; however, multiple myeloma less commonly manifests with extramedullary plasmacytomas and is less likely given his normal renal function and calcium level. Bone lesions lessen the likelihood of GPA, and his necrotic lung mass makes sarcoidosis unlikely. Atypical infections and cancers are the prime suspect of his multisystemic disease.

There are no data yet to suggest a weakened immune system, which would increase his risk for atypical infections. His chronic lung disease, identified on imaging, is a risk factor for nocardiosis. This gram-positive, weakly acid-fast bacterium can involve any organ, although lung, brain, and skin are most commonly involved. Disseminated nocardiosis can result from a pulmonary or cutaneous site of origin. Mycobacteria; Actinomyces; dimorphic fungi like Histoplasma, Coccidioides, and Blastomyces; and molds such as Aspergillus can also cause disseminated disease with pulmonary, cutaneous, and musculoskeletal manifestations.

While metastases to muscle itself are rare, they can occur with primary lung cancers. Primary lung cancer with extrapulmonary features is feasible. Squamous cell lung cancer is the most likely to cavitate, although it rarely spreads to the skin. An aggressive lymphoma like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma or cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (higher occurrence in Asians) might also explain his constellation of findings. If culture data remain negative, then biopsy of the chest wall mass might be the safest and highest-yield target.

On hospital day 2, the patient developed new-onset severe neck pain. Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical, thoracic, and lumbar spine revealed multilevel, bony, lytic lesions with notable cortical breakthrough of the C2 and C3 vertebrae into the prevertebral space, as well as epidural extension and paraspinal soft-tissue extension of the thoracic and lumbar vertebral lesions (Figure 3).

On hospital day 3, the patient reported increased tenderness in his skin nodules with one on his left forearm spontaneously draining purulent fluid. Repeat complete blood count demonstrated a white blood cell count of 12,600/mm3 (45% neutrophils, 43% lymphocytes, 8.4% monocytes, and 4.3% eosinophils), hemoglobin of 16 g/dL, and platelet count of 355,000/mm3.

The erosion into the manubrium and cortical destruction of the cervical spine attests to the aggressiveness of the underlying disease process. Noncutaneous lymphoma and lung cancer are unlikely to have such prominent skin findings; the visceral pathology, necrotizing lung mass, and bone lesions make cutaneous lymphoma less likely. At this point, a disseminated infectious process is most likely. Leading considerations based on his emigration from China and residence in California are tuberculosis and coccidioidomycosis, respectively. Tuberculous spondylitis most commonly involves the lower thoracic and upper lumbar region, and less commonly the cervical spine. His three negative AFB sputa samples further reduce its posttest probability. Ultimately microbiologic data are needed to distinguish between a disseminated fungal process, like coccidioidomycosis, or tuberculosis.

Given the concern for malignancy, a fine needle aspiration of the left supraclavicular lymph node was pursued. This revealed fungal microorganisms morphologically compatible with Coccidioides spp. with a background of necrotizing granulomas and acute inflammation. Fungal blood cultures grew Coccidioides immitis. AFB blood cultures were discontinued due to overgrowth of mold. The Coccidioides immitis antibody immunodiffusion titer was positive at 1:256.

During the remainder of the hospitalization, the patient was treated with oral fluconazole 800 mg daily. The patient underwent surgical debridement of the manubrium. In addition, given the concern for cervical spine instability, neurosurgery recommended follow-up with interval imaging. Since his discharge from the hospital, the patient continues to take oral fluconazole with resolution of his cutaneous lesions and respiratory symptoms. His titers have incrementally decreased from 1:256 to 1:16 after 8 months of treatment.

COMMENTARY

This elderly gentleman from China presented with subacute symptoms and was found to have numerous cutaneous nodules, lymphadenopathy, and diffuse osseous lesions. This multisystem illness posed a diagnostic challenge, forcing our discussant to search for a disease process that could lead to such varied findings. Ultimately, epidemiologic and clinical clues suggested a diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis, which was later confirmed on lymph node biopsy.

Coccidioides species are important fungal pathogens in the Western Hemisphere. This organism exhibits dimorphism, existing as mycelia (with arthroconidia) in soil and spherules in tissues. Coccidioides spp are endemic to the Southwestern United States, particularly California’s central valley and parts of Arizona; it additionally remains an important pathogen in Mexico, Central America, and South America.1 Newer epidemiologic studies have raised concerns that the incidence of coccidioidomycosis is increasing and that its geographic range may be more extensive than previously appreciated, with it now being found as far north as Washington state.2

Coccidioidal infection can take several forms. One-half to two-thirds of infections may be asymptomatic.3 Clinically significant infections can include an acute self-limiting respiratory illness, pulmonary nodules and cavities, chronic fibrocavitary pneumonia, and infections with extrapulmonary dissemination. Early respiratory infection is often indistinguishable from typical community-acquired pneumonia (10%-15% of pneumonia in endemic areas) but can be associated with certain suggestive features, such as erythema nodosum, erythema multiforme, prominent arthralgias (ie, “desert rheumatism”), and a peripheral eosinophilia.4,5

Extrapulmonary dissemination is rare and most commonly associated with immunocompromising states.6 However, individuals of African or Filipino ancestry also appear to be at increased risk for disseminated disease, which led to a California court decision that excluded African American inmates from state prisons located in Coccidioides endemic areas.7 The most common sites of extrapulmonary dissemination include the skin and soft tissues, bones and joints, and the central nervous system (CNS).6 CNS disease has a predilection to manifest as a chronic basilar meningitis, most often complicated by hydrocephalus, vasculitic infarction, and spinal arachnoiditis.8

Cutaneous manifestations of coccidioidomycosis can occur as immunologic phenomenon associated with pulmonary disease or represent skin and soft tissue foci of disseminated infection.9 In primary pulmonary infection, skin findings can range from a nonspecific exanthem to erythema nodosum and erythema multiforme, which are thought to represent hypersensitivity responses. In contrast, Coccidioides spp can infect the skin either through direct inoculation (as in primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis) or via hematogenous dissemination.9,10 A variety of lesions have been described, with painless nodules being the most frequently encountered morphotype in one study.11,12 On histopathologic examination, these lesions often have features of granulomatous dermatitis, eosinophilic infiltration, gummatous necrosis, microabscesses, or perivascular inflammation.13

Another common and highly morbid site of extrapulmonary dissemination is the musculoskeletal system. Bone and joint coccidioidomycosis most frequently affect the axial skeleton, although peripheral skeletal structures and joints can also be involved.6,12 Vertebral coccidioidomycosis is associated with significant morbidity. A study describing the magnetic resonance imaging findings of patients with vertebral coccidioidomycosis found that Coccidioides spp appeared to have a predilection for the thoracic vertebrae (in up to 80% of the study’s cohort).14 Skip lesions with noncontiguously involved vertebrae occurred in roughly half of patients, highlighting the usefulness of imaging the total spine in suspected cases.

The diagnosis of coccidioidomycosis is often established through serologic testing or by isolation of Coccidioides spp. on histopathology or culture. Obtaining sputum or tissue may be difficult, so clinicians often rely on noninvasive diagnostic tests such as coccidioidal antigen and serologies by enzyme immunoassays, immunodiffusion, and complement fixation. Enzyme immunoassays IgM and IgG results are positive early in the disease process and need to be confirmed with immunodiffusion or complement fixation testing. Complement fixation IgG is additionally useful to monitor disease activity over time and can help inform risk of disseminated disease.15 The gold standard of diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis infection remains histopathologic confirmation either by direct visualization of a spherule or growth in fungal cultures.16 Polymerase chain reaction testing of sputum samples is an emerging diagnostic technique that has been found to have similar sensitivity rates to fungal culture.17

Treatment decisions in coccidioidomycosis are complex and vary by site of infection, immune status of the host, and extent of disease.16 While uncomplicated primary pulmonary infections can often be managed with observation alone, prolonged medical therapy with azole antifungals is often recommended for complicated pulmonary infections, symptomatic cavitary disease, and virtually all forms of extrapulmonary disease. Intravenous liposomal amphotericin is often used as initial therapy in immunosuppressed individuals, pregnant women, and those with extensive disease. CNS disease represents a particularly challenging treatment scenario and requires lifelong azole therapy.8,16

The patient in this case initially presented with vague inflammatory symptoms, with each aliquot revealing further evidence of a metastatic disease process. Such multisystem presentations are diagnostically challenging and force clinicians to reach for some feature around which to build their differential diagnosis. It is with this in mind that we are often taught to “localize the lesion” in order to focus our search for a unifying diagnosis. Yet, in this case, the sheer number of disease foci ultimately helped the discussant to narrow the range of diagnostic possibilities because only a limited number of conditions could present with such widespread, multisystem manifestations. Therefore, this case serves as a reminder that, sometimes in clinical reasoning, “more is less.”

KEY TEACHING POINTS

- Coccidioidomycosis is a fungal infection that can present with pulmonary or extrapulmonary disease. Risk of extrapulmonary dissemination is greatest among immunocompromised individuals and those of African or Filipino ancestry.3,7

- The most common sites of extrapulmonary dissemination include the skin and soft tissues, bones and joints, and the CNS.6

- While serologic testing can be diagnostically useful, the gold standard for diagnosis of disseminated coccidioidomycosis infection remains histopathologic confirmation with direct visualization of a spherule or growth in fungal cultures.16

1. Benedict K, McCotter OZ, Brady S, et al. Surveillance for Coccidioidomycosis - United States, 2011-2017. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2019;68(No. SS-7):1-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6807a1

2. McCotter OZ, Benedict K, Engelthaler DM, et al. Update on the epidemiology of coccidioidomycosis in the United States. Med Mycol. 2019;57(Suppl 1):S30-s40. https://doi.org/10.1093/mmy/myy095

3. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. Coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;41(9):1217-1223. https://doi.org/10.1086/496991

4. Chang DC, Anderson S, Wannemuehler K, et al. Testing for coccidioidomycosis among patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(7):1053-1059. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1407.070832

5. Saubolle MA, McKellar PP, Sussland D. Epidemiologic, clinical, and diagnostic aspects of coccidioidomycosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(1):26-30. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.02230-06

6. Adam RD, Elliott SP, Taljanovic MS. The spectrum and presentation of disseminated coccidioidomycosis. Am J Med. 2009;122(8):770-777. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.12.024

7. Wheeler C, Lucas KD, Mohle-Boetani JC. Rates and risk factors for Coccidioidomycosis among prison inmates, California, USA, 2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(1):70-75. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2101.140836

8. Johnson RH, Einstein HE. Coccidioidal meningitis. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42(1):103-107. https://doi.org/10.1086/497596

9. Blair JE. State-of-the-art treatment of coccidioidomycosis: skin and soft-tissue infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1111:411-421. https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1406.010

10. Chang A, Tung RC, McGillis TS, Bergfeld WF, Taylor JS. Primary cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(5):944-949. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0190-9622(03)00462-6

11. Quimby SR, Connolly SM, Winkelmann RK, Smilack JD. Clinicopathologic spectrum of specific cutaneous lesions of disseminated coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26(1):79-85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0190-9622(92)70011-4

12. Crum NF, Lederman ER, Stafford CM, Parrish JS, Wallace MR. Coccidioidomycosis: a descriptive survey of a reemerging disease. clinical characteristics and current controversies. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83(3):149-175. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.md.0000126762.91040.fd

13. Carpenter JB, Feldman JS, Leyva WH, DiCaudo DJ. Clinical and pathologic characteristics of disseminated cutaneous coccidioidomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(5):831-837. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2008.07.031

14. Crete RN, Gallmann W, Karis JP, Ross J. Spinal coccidioidomycosis: MR imaging findings in 41 patients. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2018;39(11):2148-2153. https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.a5818

15. McHardy IH, Dinh BN, Waldman S, et al. Coccidioidomycosis complement fixation titer trends in the age of antifungals. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56(12):e01318-18. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01318-18

16. Galgiani JN, Ampel NM, Blair JE, et al. 2016 Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) clinical practice guideline for the treatment of coccidioidomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63(6):e112-e146. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw360

17. Vucicevic D, Blair JE, Binnicker MJ, et al. The utility of Coccidioides polymerase chain reaction testing in the clinical setting. Mycopathologia. 2010;170(5):345-351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-010-9327-0

A 64-year-old man presented with a 2-month history of a nonproductive cough, weight loss, and subjective fevers. He had no chest pain, hemoptysis, or shortness of breath. He also described worsening anorexia and a 15-pound weight loss over the previous 3 months. He had no arthralgias, myalgias, abdominal pain, nausea, emesis, or diarrhea.

Two weeks prior to his presentation, he was diagnosed with pneumonia and given a 5-day course of azithromycin. His symptoms did not improve, so he presented to the emergency room.

He had not been seen regularly by a physician in decades and had no known medical conditions. He did not take any medications. He immigrated from China 3 years prior and lived with his wife in California. He had a 30 pack-year smoking history. He drank a shot glass of liquor daily and denied any drug use.

Weight loss might result from inflammatory disorders like cancer or noninflammatory causes such as decreased oral intake (eg, diminished appetite) or malabsorption (eg, celiac disease). However, his fevers suggest inflammation, which usually reflects an underlying infection, cancer, or autoimmune process. While chronic cough typically results from upper airway cough syndrome (allergic or nonallergic rhinitis), gastroesophageal reflux disease, or asthma, it can also point to pathology of the lung, which may be intrinsic (bronchiectasis) or extrinsic (mediastinal mass). The duration of 2 months makes a typical infectious process like pneumococcal pneumonia unlikely. Atypical infections such as tuberculosis, melioidosis, and talaromycosis are possible given his immigration from East Asia, and coccidioidomycosis given his residence in California. He might have undiagnosed medical conditions, such as diabetes, that could be relevant to his current presentation and classify him as immunocompromised. His smoking history prompts consideration of lung cancer.

His temperature was 36.5 oC, heart rate 70 beats per minute, blood pressure 118/66 mm Hg, respiratory rate 16 breaths per minute, oxygen saturation 98% on room air, and body mass index 23 kg/m2. He was in no acute distress. The findings from the cardiac, lung, abdominal, and neurological exams were normal.

Skin examination found a fixed, symmetric, 5-cm, firm nodule at top of sternum (Figure 1A). In addition, he had two 1-cm, mobile, firm, subcutaneous nodules, one on his anterior left chest and another underneath his right axilla. He also had two 2-cm, erythematous, tender nodules on his left anterior forearm and a 1-cm nodule with a central black plug on the dorsal surface of his right hand (Figure 1B). He did not have any edema.

The white blood cell count was 10,500/mm3 (42% neutrophils, 37% lymphocytes, 16.4% monocytes, and 2.9% eosinophils), hemoglobin was 12.2 g/dL with a mean corpuscular volume of 91 fL, and the platelet count was 441,000/mm3. Basic metabolic panel, aminotransferase, bilirubin, and alkaline phosphatase were within reference ranges. Serum albumin was 3.1 g/dL. Serum total protein was elevated at 8.8 g/dL. Serum calcium was 9.0 mg/dL. Urinalysis results were normal.

The slightly low albumin, mildly elevated platelet count, monocytosis, and normocytic anemia suggest inflammation, although monocytosis might represent a hematologic malignancy like chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML). His subjective fevers and weight loss further corroborate underlying inflammation. What is driving the inflammation? There are two localizing findings: cough and nodular skin lesions.

His lack of dyspnea and normal oxygen saturation, respiratory rate, and lung exam make an extrapulmonary cause of cough such as lymphadenopathy or mediastinal infection possible. The number of nodular skin lesions, wide-spread distribution, and appearance (eg, erythematous, tender) point to either a primary cutaneous disease with systemic manifestations (eg, cutaneous lymphoma) or a systemic disease with cutaneous features (eg, sarcoidosis).

Three categories—inflammatory, infectious, and neoplastic—account for most nodular skin lesions. Usually microscopic evaluation is necessary for definitive diagnosis, though epidemiology, associated symptoms, and characteristics of the nodules help prioritize the differential diagnosis. Tender nodules might reflect a panniculitis; erythema nodosum is the most common type, and while this classically develops on the anterior shins, it may also occur on the forearm. His immigration from China prompts consideration of tuberculosis and cutaneous leishmaniasis. Coccidioidomycosis can lead to inflammation and nodular skin lesions. Other infections such as nontuberculous mycobacteria, nocardiosis, and cryptococcosis may cause disseminated infection with pulmonary and skin manifestations. His smoking puts him at risk of lung cancer, which rarely results in metastatic subcutaneous infiltrates.

A chest radiograph demonstrated a prominent density in the right paratracheal region of the mediastinum with adjacent streaky opacities. A computed tomography scan of the chest with intravenous contrast demonstrated centrilobular emphysematous changes and revealed a 2.6 × 4.7-cm necrotic mass in the anterior chest wall with erosion into the manubrium, a 3.8 × 2.1-cm centrally necrotic soft-tissue mass in the right hilum, a 5-mm left upper-lobe noncalcified solid pulmonary nodule, and prominent subcarinal, paratracheal, hilar, and bilateral supraclavicular lymphadenopathy (Figure 2).

Flow cytometry of the peripheral blood did not demonstrate a lymphoproliferative disorder. Blood smear demonstrated normal red blood cell, white blood cell, and platelet morphology. HIV antibody was negative. Hemoglobin A1c was 6.1%. Smear microscopy for acid-fast bacilli (AFB) was negative and sputum AFB samples were sent for culture. Bacterial, fungal, and AFB blood cultures were collected and pending.

Causes of necrotizing pneumonia include liquid (eg, lymphoma) and solid (eg, squamous cell carcinoma) cancers, infections, and noninfectious inflammatory processes such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). Given his subacute presentation and extrapulmonary cutaneous manifestations, consideration of mycobacteria, fungi (eg, Coccidioides, Aspergillus, and Cryptococcus), and filamentous bacteria (eg, Nocardia and Actinomyces) is prioritized among the myriad of infections that can cause a lung cavity. His smoking history and centrilobular emphysematous changes are highly suggestive of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which puts him at increased risk of bacterial colonization and recurrent pulmonary infections. Tuberculosis is still possible despite three negative AFB-sputa smears given the sensitivity of smear microscopy (with three specimens) is roughly 70% in an immunocompetent host.

The lymphadenopathy likely reflects spread from the necrotic lung mass. The frequency of non-Hodgkin lymphoma increases with age. The results of the peripheral flow cytometry do not exclude the possibility of an aggressive lymphoma with pulmonary and cutaneous manifestations.

The erosive property of the chest wall mass makes an autoimmune process like GPA unlikely. An aggressive and disseminated infection or cancer is most likely. A pathologic process that originated in the lung and then spread to the lymph nodes and skin is more likely than a disorder which started in the skin. It would be unlikely for a primary cutaneous disorder to cause such a well-defined necrotic lung mass. Lung cancer rarely metastasizes to the skin and, instead, preferentially involves the chest. Ultimately, ascertaining what the patient experienced first (ie, respiratory or cutaneous symptoms) will determine where the pathology originated.

Computed tomography scan of the abdomen and pelvis with intravenous contrast demonstrated multiple ill-defined lytic lesions in the pelvis, including a 12-mm lesion of the left sacral ala and multiple subcentimeter lesions in the medial left iliac bone and superior right acetabulum. In addition, there were two 1-cm, rim-enhancing, hypodense nodules in the subcutaneous fat of the right flank at the level of L5 and the left lower quadrant, respectively. There was also a 2.2 × 1.9-cm faintly rim-enhancing hypodensity within the left iliopsoas muscle belly.

These imaging findings further corroborate a widely metastatic process probably originating in the lung and spreading to the lymph nodes, skin, muscles, and bones. The characterization of lesions as lytic as opposed to blastic is less helpful because many diseases can cause both. It does prompt consideration of multiple myeloma; however, multiple myeloma less commonly manifests with extramedullary plasmacytomas and is less likely given his normal renal function and calcium level. Bone lesions lessen the likelihood of GPA, and his necrotic lung mass makes sarcoidosis unlikely. Atypical infections and cancers are the prime suspect of his multisystemic disease.