User login

Evaluation of a Dementia Resource Fair for Veterans, Caregivers, and Staff

Due to the increasing number of older adults, the annual number of new cases of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia is projected to double by 2050.1 The cost of caring for persons with dementia is rising as well. In 2015, the expected health care cost for persons with dementia in the U.S. is estimated to be $226 billion.1 There is a growing awareness of the needs of persons with dementia and of the importance of providing caregivers with support and education that enables them to keep their loved ones at home as long as possible. Additionally, caregiver stress adversely affects health and increases mortality risk.2-4 Efficacious interventions that teach caregivers to cope with challenging behaviors and functional decline are also available.5,6 Yet many caregivers encounter barriers that prevent access to these interventions. Some may not be able to access interventions due to lack of insurance plan coverage; others may not have the time to participate in these programs.7,8

The VA has requested that its VISNs and VAMCs develop dementia committees so that VA employees can establish goals focused on improving dementia care. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Dementia Committee determined that veterans, caregivers, and staff needed simple, clear information about dementia, based on consensus opinion. In 2013, one of the committee co-chairs, a clinical nurse specialist in the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), introduced the concept of a dementia resource fair. There is evidence supporting the use of interdisciplinary health fairs to educate allied health trainees (eg, nursing students and social workers) through service learning.9 But to the authors’ knowledge, the use of such a fair to provide dementia information has not been evaluated.

The fair drew from the evidence base for formal psychoeducational interventions for caregiversand for those with dementia or cognitive impairment.10,11 The goal of the fair was to provide information about resources for and management of dementia to veterans, families, staff, caregivers, and the community, using printed material and consultation with knowledgeable staff. The GRECC staff also initiated a systematic evaluation of this new initiative and collaborated with the Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center staff on the evaluation process.

Initial Plan

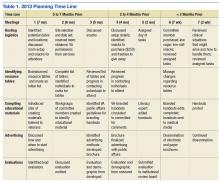

A subcommittee, composed of interdisciplinary professionals who work with veterans diagnosed with dementia, planned the initial dementia resource fair. The subcommittee representatives included geriatric medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy, psychology, recreational therapy, and social work. Subcommittee members were charged with developing VA-branded handouts as educational tools to address key issues related to dementia, such as advance directive planning, behavioral management, home safety, and medication management. The subcommittee met monthly for 6 months and focused on logistics, identification of resource tables, creation of educational materials, advertising, and development of an evaluation. Table 1 provides an overview of the planning time line for the 2013 fair held in San Jose. Findings from a systematic evaluation of the 2013 fair were used to improve the 2015 fair held in Menlo Park. A discussion about the evaluation method and results follows.

Methods

The first fair was held at a VA community-based outpatient clinic in a small conference room with 13 resource tables. Feedback from attendees in 2013 included suggestions for having more tables, larger event space, more publicity, and alternate locations for the fair. In response to the feedback, the 2015 fair was held at a division of the main VAMC in a large conference room and hosted 20 tables arranged in a horseshoe shape. The second fair included an activity table staffed by a psychology fellow and recreation therapist who provided respite to caregivers if their loved one with dementia accompanied them to the event. Both the 2013 and 2015 fairs were 4 hours long.

A 1-page, anonymous survey was developed to assess attendees’ opinions about the fair. The survey included information about whether attendees were caregivers, veterans, or VA staff but did not ask other demographic questions to preserve anonymity. In 2013, the survey asked attendees to choose the category that best described them, but in 2015, the survey asked attendees to indicate the number of individuals from each category in their party. The 2015 survey assessed 2 additional categories (family member, other) and added a question about the number of people in each party to better estimate attendance. Both surveys also asked attendees to check which resource tables they visited.

The following assessment questions were consistent across both fairs to allow for comparisons. The authors assessed attitudes and learning as a result of the fair, using 2 statements that were rated with a 5-point Likert scale. The authors asked 3 open-ended questions to ascertain the helpful aspects of the fair, unmet needs, and suggestions for improvement. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed this program evaluation plan and determined that the program evaluation project did not require IRB approval.

When attendees arrived at the fair, they received a folder containing branded handouts, a reusable bag, and a survey. Committee members asked that 1 person per party complete the survey at the end of the visit. Attendees visited tables, obtained written materials, and spoke with subcommittee members who staffed the tables. Snacks and light refreshments were provided. The reusable bag was provided by the VAMC Suicide Prevention Program to increase awareness of the VAPAHCS Suicide Prevention Program. As attendees were leaving, they were reminded to complete the survey. Attendees deposited completed surveys in a box to ensure anonymity.

Results

Thirty-six individuals attended the 2013 fair, and 138 individuals attended the 2015 fair. Thirty-one surveys were completed in 2013, yielding an 86% response rate. One hundred six surveys were returned and represented responses for 129 individuals in 2015, yielding a 94% response rate in 2015. Most of the 2013 attendees were caregivers, followed by veterans, VA staff, and outside staff (Table 2). In contrast, most of the 2015 attendees were VA staff, followed by veterans, caregivers/family members, outside staff, and others. Distributions of attendees differed significantly across the fairs: χ2(4) = 12.66; P = .01.

The surveys assessed which tables attendees visited and their perceptions of the fair. The most frequently visited resource table for both 2013 and 2015 fairs was the Alzheimer’s Association table. Other popular resource tables were VA Benefits and VA Caregiver Support in 2013 and Home Safety and End of Life Care in 2015. Ninety-six percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees strongly agreed or agreed that “attending the dementia fair was worth my time and effort.” Eighty-three percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees felt that they had learned something useful at the fair. The proportion of individuals reporting that they had learned something useful significantly increased from 2013 to 2015: χ2(2) = 18.07; P = .0001.

To summarize the open-ended responses to the question “What was most helpful about the fair?” the authors constructed a word cloud that displays the 75 most frequently used words in attendees’ descriptions of the 2015 fair (Figure). Attendees provided suggestions about additional information and resources they desired, which included VA benefits enrollment, books and movies about dementia (eg, Still Alice), speech and swallowing disorders representatives, varied types of advance directives, class discussion, question-and-answer time with speakers, and resources for nonveteran older adults. General suggestions for future fairs included hosting the fair at the main division of the VA health care system, having more room between tables, inviting more vendors, using more visual posters at the tables, and additional advertising for VA services.

Discussion

Dementia is a costly disease with detrimental health and well-being effects on caregivers. The dementia resource fairs aimed to connect caregivers with resources for veterans with dementia in the VA and in the community. Given that nearly half the 2015 fair attendees were VA staff, there is an apparent need for increasing dementia education and access to care resource for this VAMC’s workforce. The high proportion of staff attendees at the 2015 fair may be attributed to the 2 VA community living centers at the VAMC site where the fair was held. This unexpected finding points to the importance of informal and interactive education opportunities for staff, particularly those working with veterans with dementia. The fair served an important role for VA staff seeking information on dementia for professional and personal reasons. This systematic evaluation of the fair demonstrated a need for improving access to information about dementia.

The idea of hosting a dementia resource fair was met with enthusiasm from attendees and subcommittee members in 2013. Feedback helped refine the second fair. The increase in self-reported learning from 2013 to 2015 suggests improvements may have been made between the first and second fair; however, this must be interpreted in light of the different compositions of the attendees at each fair and the absence of a control group. Attendees desired even more information about dementia at the second fair, as evidenced by suggestions to have presentations, speakers, and class discussions. These responses suggest that other sites may wish to consider holding similar events. Next steps include researching the effectiveness of low-cost, pragmatic educational initiatives for caregivers. In fact, randomized, controlled trials of dementia caregiver education and skill-building interventions are underway at VAPAHCS.

Conclusion

The primary lesson learned from the most recent fair was that marketing is the key to success. The authors created an efficient hospital publicity plan in 2015 that included (1) flyers posted throughout 2 main medical center campuses; (2) announcements on closed-circuit VA waiting room televisions; (3) e-mail announcements sent to staff; and (4) VA social media announcements. Flyers also were mailed to known caregivers, and announcements of the event were provided to local community agencies. This focus on publicity likely contributed to the substantial increase in participation from the 2013 to 2015 fair.

Future fairs may be improved by providing more detailed information about dementia through formal presentations. The authors aim to increase the number of family caregivers in attendance possibly through coordinating the fair to coincide with primary care clinic hours, advertising the availability of brief respite at the fair, and conducting additional outreach to veterans.

This systematic evaluation of the dementia resource fair confirmed that providing resources in a drop-in setting resulted in self-reported learning about resources available for veterans with dementia. VA dementia care providers are encouraged to use the authors’ time line and lessons learned to develop dementia resource fairs for their sites.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the 2013 and 2015 Dementia Resource Fair Committees, chaired by Betty Wexler and Kathleen McConnell, respectively. Dr. Gould is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001478) and by Ellen Schapiro & Gerald Axelbaum through a 2014 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Scanlon is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001240; I21 RX001710), U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-15-1-0246), Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, and Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center. Drs. Gould and Scanlon also receive support from Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3)332-384.

2. Schulz R, Beach SR, Cook TB, Martire LM, Tomlinson JM, Monin JK. Predictors and consequences of perceived lack of choice in becoming an informal caregiver. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(6):712-721.

3. Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, et al; World Federation of Biological Psychiatry – Old Age Taskforce. Systematic review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(6):856-870.

4. Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1991;282(23):2215-2219.

5. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946-953.

6. Gitlin LN. Good news for dementia care: caregiver interventions reduce behavioral symptoms in people with dementia and family distress. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):894-897.

7. Ho A, Collins SR, Davis K, Doty MM. A look at working-age caregivers roles, health concerns, and need for support. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2005;(854):1-12.

8. Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Smit F, et al. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? A randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30936.

9. Kolomer S, Quinn ME, Steele K. Interdisciplinary health fairs for older adults and the value of interprofessional service learning. J Community Pract. 2010;18(2-3):267-279.

10. Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):130-143.

11. Quinn C, Toms G, Anderson D, Clare L. A review of self-management interventions for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;pii:0733464814566852.

Due to the increasing number of older adults, the annual number of new cases of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia is projected to double by 2050.1 The cost of caring for persons with dementia is rising as well. In 2015, the expected health care cost for persons with dementia in the U.S. is estimated to be $226 billion.1 There is a growing awareness of the needs of persons with dementia and of the importance of providing caregivers with support and education that enables them to keep their loved ones at home as long as possible. Additionally, caregiver stress adversely affects health and increases mortality risk.2-4 Efficacious interventions that teach caregivers to cope with challenging behaviors and functional decline are also available.5,6 Yet many caregivers encounter barriers that prevent access to these interventions. Some may not be able to access interventions due to lack of insurance plan coverage; others may not have the time to participate in these programs.7,8

The VA has requested that its VISNs and VAMCs develop dementia committees so that VA employees can establish goals focused on improving dementia care. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Dementia Committee determined that veterans, caregivers, and staff needed simple, clear information about dementia, based on consensus opinion. In 2013, one of the committee co-chairs, a clinical nurse specialist in the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), introduced the concept of a dementia resource fair. There is evidence supporting the use of interdisciplinary health fairs to educate allied health trainees (eg, nursing students and social workers) through service learning.9 But to the authors’ knowledge, the use of such a fair to provide dementia information has not been evaluated.

The fair drew from the evidence base for formal psychoeducational interventions for caregiversand for those with dementia or cognitive impairment.10,11 The goal of the fair was to provide information about resources for and management of dementia to veterans, families, staff, caregivers, and the community, using printed material and consultation with knowledgeable staff. The GRECC staff also initiated a systematic evaluation of this new initiative and collaborated with the Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center staff on the evaluation process.

Initial Plan

A subcommittee, composed of interdisciplinary professionals who work with veterans diagnosed with dementia, planned the initial dementia resource fair. The subcommittee representatives included geriatric medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy, psychology, recreational therapy, and social work. Subcommittee members were charged with developing VA-branded handouts as educational tools to address key issues related to dementia, such as advance directive planning, behavioral management, home safety, and medication management. The subcommittee met monthly for 6 months and focused on logistics, identification of resource tables, creation of educational materials, advertising, and development of an evaluation. Table 1 provides an overview of the planning time line for the 2013 fair held in San Jose. Findings from a systematic evaluation of the 2013 fair were used to improve the 2015 fair held in Menlo Park. A discussion about the evaluation method and results follows.

Methods

The first fair was held at a VA community-based outpatient clinic in a small conference room with 13 resource tables. Feedback from attendees in 2013 included suggestions for having more tables, larger event space, more publicity, and alternate locations for the fair. In response to the feedback, the 2015 fair was held at a division of the main VAMC in a large conference room and hosted 20 tables arranged in a horseshoe shape. The second fair included an activity table staffed by a psychology fellow and recreation therapist who provided respite to caregivers if their loved one with dementia accompanied them to the event. Both the 2013 and 2015 fairs were 4 hours long.

A 1-page, anonymous survey was developed to assess attendees’ opinions about the fair. The survey included information about whether attendees were caregivers, veterans, or VA staff but did not ask other demographic questions to preserve anonymity. In 2013, the survey asked attendees to choose the category that best described them, but in 2015, the survey asked attendees to indicate the number of individuals from each category in their party. The 2015 survey assessed 2 additional categories (family member, other) and added a question about the number of people in each party to better estimate attendance. Both surveys also asked attendees to check which resource tables they visited.

The following assessment questions were consistent across both fairs to allow for comparisons. The authors assessed attitudes and learning as a result of the fair, using 2 statements that were rated with a 5-point Likert scale. The authors asked 3 open-ended questions to ascertain the helpful aspects of the fair, unmet needs, and suggestions for improvement. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed this program evaluation plan and determined that the program evaluation project did not require IRB approval.

When attendees arrived at the fair, they received a folder containing branded handouts, a reusable bag, and a survey. Committee members asked that 1 person per party complete the survey at the end of the visit. Attendees visited tables, obtained written materials, and spoke with subcommittee members who staffed the tables. Snacks and light refreshments were provided. The reusable bag was provided by the VAMC Suicide Prevention Program to increase awareness of the VAPAHCS Suicide Prevention Program. As attendees were leaving, they were reminded to complete the survey. Attendees deposited completed surveys in a box to ensure anonymity.

Results

Thirty-six individuals attended the 2013 fair, and 138 individuals attended the 2015 fair. Thirty-one surveys were completed in 2013, yielding an 86% response rate. One hundred six surveys were returned and represented responses for 129 individuals in 2015, yielding a 94% response rate in 2015. Most of the 2013 attendees were caregivers, followed by veterans, VA staff, and outside staff (Table 2). In contrast, most of the 2015 attendees were VA staff, followed by veterans, caregivers/family members, outside staff, and others. Distributions of attendees differed significantly across the fairs: χ2(4) = 12.66; P = .01.

The surveys assessed which tables attendees visited and their perceptions of the fair. The most frequently visited resource table for both 2013 and 2015 fairs was the Alzheimer’s Association table. Other popular resource tables were VA Benefits and VA Caregiver Support in 2013 and Home Safety and End of Life Care in 2015. Ninety-six percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees strongly agreed or agreed that “attending the dementia fair was worth my time and effort.” Eighty-three percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees felt that they had learned something useful at the fair. The proportion of individuals reporting that they had learned something useful significantly increased from 2013 to 2015: χ2(2) = 18.07; P = .0001.

To summarize the open-ended responses to the question “What was most helpful about the fair?” the authors constructed a word cloud that displays the 75 most frequently used words in attendees’ descriptions of the 2015 fair (Figure). Attendees provided suggestions about additional information and resources they desired, which included VA benefits enrollment, books and movies about dementia (eg, Still Alice), speech and swallowing disorders representatives, varied types of advance directives, class discussion, question-and-answer time with speakers, and resources for nonveteran older adults. General suggestions for future fairs included hosting the fair at the main division of the VA health care system, having more room between tables, inviting more vendors, using more visual posters at the tables, and additional advertising for VA services.

Discussion

Dementia is a costly disease with detrimental health and well-being effects on caregivers. The dementia resource fairs aimed to connect caregivers with resources for veterans with dementia in the VA and in the community. Given that nearly half the 2015 fair attendees were VA staff, there is an apparent need for increasing dementia education and access to care resource for this VAMC’s workforce. The high proportion of staff attendees at the 2015 fair may be attributed to the 2 VA community living centers at the VAMC site where the fair was held. This unexpected finding points to the importance of informal and interactive education opportunities for staff, particularly those working with veterans with dementia. The fair served an important role for VA staff seeking information on dementia for professional and personal reasons. This systematic evaluation of the fair demonstrated a need for improving access to information about dementia.

The idea of hosting a dementia resource fair was met with enthusiasm from attendees and subcommittee members in 2013. Feedback helped refine the second fair. The increase in self-reported learning from 2013 to 2015 suggests improvements may have been made between the first and second fair; however, this must be interpreted in light of the different compositions of the attendees at each fair and the absence of a control group. Attendees desired even more information about dementia at the second fair, as evidenced by suggestions to have presentations, speakers, and class discussions. These responses suggest that other sites may wish to consider holding similar events. Next steps include researching the effectiveness of low-cost, pragmatic educational initiatives for caregivers. In fact, randomized, controlled trials of dementia caregiver education and skill-building interventions are underway at VAPAHCS.

Conclusion

The primary lesson learned from the most recent fair was that marketing is the key to success. The authors created an efficient hospital publicity plan in 2015 that included (1) flyers posted throughout 2 main medical center campuses; (2) announcements on closed-circuit VA waiting room televisions; (3) e-mail announcements sent to staff; and (4) VA social media announcements. Flyers also were mailed to known caregivers, and announcements of the event were provided to local community agencies. This focus on publicity likely contributed to the substantial increase in participation from the 2013 to 2015 fair.

Future fairs may be improved by providing more detailed information about dementia through formal presentations. The authors aim to increase the number of family caregivers in attendance possibly through coordinating the fair to coincide with primary care clinic hours, advertising the availability of brief respite at the fair, and conducting additional outreach to veterans.

This systematic evaluation of the dementia resource fair confirmed that providing resources in a drop-in setting resulted in self-reported learning about resources available for veterans with dementia. VA dementia care providers are encouraged to use the authors’ time line and lessons learned to develop dementia resource fairs for their sites.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the 2013 and 2015 Dementia Resource Fair Committees, chaired by Betty Wexler and Kathleen McConnell, respectively. Dr. Gould is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001478) and by Ellen Schapiro & Gerald Axelbaum through a 2014 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Scanlon is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001240; I21 RX001710), U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-15-1-0246), Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, and Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center. Drs. Gould and Scanlon also receive support from Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research.

Due to the increasing number of older adults, the annual number of new cases of Alzheimer disease and other types of dementia is projected to double by 2050.1 The cost of caring for persons with dementia is rising as well. In 2015, the expected health care cost for persons with dementia in the U.S. is estimated to be $226 billion.1 There is a growing awareness of the needs of persons with dementia and of the importance of providing caregivers with support and education that enables them to keep their loved ones at home as long as possible. Additionally, caregiver stress adversely affects health and increases mortality risk.2-4 Efficacious interventions that teach caregivers to cope with challenging behaviors and functional decline are also available.5,6 Yet many caregivers encounter barriers that prevent access to these interventions. Some may not be able to access interventions due to lack of insurance plan coverage; others may not have the time to participate in these programs.7,8

The VA has requested that its VISNs and VAMCs develop dementia committees so that VA employees can establish goals focused on improving dementia care. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Dementia Committee determined that veterans, caregivers, and staff needed simple, clear information about dementia, based on consensus opinion. In 2013, one of the committee co-chairs, a clinical nurse specialist in the Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC), introduced the concept of a dementia resource fair. There is evidence supporting the use of interdisciplinary health fairs to educate allied health trainees (eg, nursing students and social workers) through service learning.9 But to the authors’ knowledge, the use of such a fair to provide dementia information has not been evaluated.

The fair drew from the evidence base for formal psychoeducational interventions for caregiversand for those with dementia or cognitive impairment.10,11 The goal of the fair was to provide information about resources for and management of dementia to veterans, families, staff, caregivers, and the community, using printed material and consultation with knowledgeable staff. The GRECC staff also initiated a systematic evaluation of this new initiative and collaborated with the Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center staff on the evaluation process.

Initial Plan

A subcommittee, composed of interdisciplinary professionals who work with veterans diagnosed with dementia, planned the initial dementia resource fair. The subcommittee representatives included geriatric medicine, nursing, occupational therapy, pharmacy, psychology, recreational therapy, and social work. Subcommittee members were charged with developing VA-branded handouts as educational tools to address key issues related to dementia, such as advance directive planning, behavioral management, home safety, and medication management. The subcommittee met monthly for 6 months and focused on logistics, identification of resource tables, creation of educational materials, advertising, and development of an evaluation. Table 1 provides an overview of the planning time line for the 2013 fair held in San Jose. Findings from a systematic evaluation of the 2013 fair were used to improve the 2015 fair held in Menlo Park. A discussion about the evaluation method and results follows.

Methods

The first fair was held at a VA community-based outpatient clinic in a small conference room with 13 resource tables. Feedback from attendees in 2013 included suggestions for having more tables, larger event space, more publicity, and alternate locations for the fair. In response to the feedback, the 2015 fair was held at a division of the main VAMC in a large conference room and hosted 20 tables arranged in a horseshoe shape. The second fair included an activity table staffed by a psychology fellow and recreation therapist who provided respite to caregivers if their loved one with dementia accompanied them to the event. Both the 2013 and 2015 fairs were 4 hours long.

A 1-page, anonymous survey was developed to assess attendees’ opinions about the fair. The survey included information about whether attendees were caregivers, veterans, or VA staff but did not ask other demographic questions to preserve anonymity. In 2013, the survey asked attendees to choose the category that best described them, but in 2015, the survey asked attendees to indicate the number of individuals from each category in their party. The 2015 survey assessed 2 additional categories (family member, other) and added a question about the number of people in each party to better estimate attendance. Both surveys also asked attendees to check which resource tables they visited.

The following assessment questions were consistent across both fairs to allow for comparisons. The authors assessed attitudes and learning as a result of the fair, using 2 statements that were rated with a 5-point Likert scale. The authors asked 3 open-ended questions to ascertain the helpful aspects of the fair, unmet needs, and suggestions for improvement. The Stanford University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed this program evaluation plan and determined that the program evaluation project did not require IRB approval.

When attendees arrived at the fair, they received a folder containing branded handouts, a reusable bag, and a survey. Committee members asked that 1 person per party complete the survey at the end of the visit. Attendees visited tables, obtained written materials, and spoke with subcommittee members who staffed the tables. Snacks and light refreshments were provided. The reusable bag was provided by the VAMC Suicide Prevention Program to increase awareness of the VAPAHCS Suicide Prevention Program. As attendees were leaving, they were reminded to complete the survey. Attendees deposited completed surveys in a box to ensure anonymity.

Results

Thirty-six individuals attended the 2013 fair, and 138 individuals attended the 2015 fair. Thirty-one surveys were completed in 2013, yielding an 86% response rate. One hundred six surveys were returned and represented responses for 129 individuals in 2015, yielding a 94% response rate in 2015. Most of the 2013 attendees were caregivers, followed by veterans, VA staff, and outside staff (Table 2). In contrast, most of the 2015 attendees were VA staff, followed by veterans, caregivers/family members, outside staff, and others. Distributions of attendees differed significantly across the fairs: χ2(4) = 12.66; P = .01.

The surveys assessed which tables attendees visited and their perceptions of the fair. The most frequently visited resource table for both 2013 and 2015 fairs was the Alzheimer’s Association table. Other popular resource tables were VA Benefits and VA Caregiver Support in 2013 and Home Safety and End of Life Care in 2015. Ninety-six percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees strongly agreed or agreed that “attending the dementia fair was worth my time and effort.” Eighty-three percent of 2013 attendees and 100% of 2015 attendees felt that they had learned something useful at the fair. The proportion of individuals reporting that they had learned something useful significantly increased from 2013 to 2015: χ2(2) = 18.07; P = .0001.

To summarize the open-ended responses to the question “What was most helpful about the fair?” the authors constructed a word cloud that displays the 75 most frequently used words in attendees’ descriptions of the 2015 fair (Figure). Attendees provided suggestions about additional information and resources they desired, which included VA benefits enrollment, books and movies about dementia (eg, Still Alice), speech and swallowing disorders representatives, varied types of advance directives, class discussion, question-and-answer time with speakers, and resources for nonveteran older adults. General suggestions for future fairs included hosting the fair at the main division of the VA health care system, having more room between tables, inviting more vendors, using more visual posters at the tables, and additional advertising for VA services.

Discussion

Dementia is a costly disease with detrimental health and well-being effects on caregivers. The dementia resource fairs aimed to connect caregivers with resources for veterans with dementia in the VA and in the community. Given that nearly half the 2015 fair attendees were VA staff, there is an apparent need for increasing dementia education and access to care resource for this VAMC’s workforce. The high proportion of staff attendees at the 2015 fair may be attributed to the 2 VA community living centers at the VAMC site where the fair was held. This unexpected finding points to the importance of informal and interactive education opportunities for staff, particularly those working with veterans with dementia. The fair served an important role for VA staff seeking information on dementia for professional and personal reasons. This systematic evaluation of the fair demonstrated a need for improving access to information about dementia.

The idea of hosting a dementia resource fair was met with enthusiasm from attendees and subcommittee members in 2013. Feedback helped refine the second fair. The increase in self-reported learning from 2013 to 2015 suggests improvements may have been made between the first and second fair; however, this must be interpreted in light of the different compositions of the attendees at each fair and the absence of a control group. Attendees desired even more information about dementia at the second fair, as evidenced by suggestions to have presentations, speakers, and class discussions. These responses suggest that other sites may wish to consider holding similar events. Next steps include researching the effectiveness of low-cost, pragmatic educational initiatives for caregivers. In fact, randomized, controlled trials of dementia caregiver education and skill-building interventions are underway at VAPAHCS.

Conclusion

The primary lesson learned from the most recent fair was that marketing is the key to success. The authors created an efficient hospital publicity plan in 2015 that included (1) flyers posted throughout 2 main medical center campuses; (2) announcements on closed-circuit VA waiting room televisions; (3) e-mail announcements sent to staff; and (4) VA social media announcements. Flyers also were mailed to known caregivers, and announcements of the event were provided to local community agencies. This focus on publicity likely contributed to the substantial increase in participation from the 2013 to 2015 fair.

Future fairs may be improved by providing more detailed information about dementia through formal presentations. The authors aim to increase the number of family caregivers in attendance possibly through coordinating the fair to coincide with primary care clinic hours, advertising the availability of brief respite at the fair, and conducting additional outreach to veterans.

This systematic evaluation of the dementia resource fair confirmed that providing resources in a drop-in setting resulted in self-reported learning about resources available for veterans with dementia. VA dementia care providers are encouraged to use the authors’ time line and lessons learned to develop dementia resource fairs for their sites.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the members of the 2013 and 2015 Dementia Resource Fair Committees, chaired by Betty Wexler and Kathleen McConnell, respectively. Dr. Gould is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001478) and by Ellen Schapiro & Gerald Axelbaum through a 2014 NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Research Foundation. Dr. Scanlon is supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (IK2 RX001240; I21 RX001710), U.S. Department of Defense (W81XWH-15-1-0246), Sierra-Pacific Mental Illness Research Education and Clinical Center, and Stanford/VA Alzheimer’s Research Center. Drs. Gould and Scanlon also receive support from Palo Alto Veterans Institute for Research.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3)332-384.

2. Schulz R, Beach SR, Cook TB, Martire LM, Tomlinson JM, Monin JK. Predictors and consequences of perceived lack of choice in becoming an informal caregiver. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(6):712-721.

3. Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, et al; World Federation of Biological Psychiatry – Old Age Taskforce. Systematic review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(6):856-870.

4. Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1991;282(23):2215-2219.

5. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946-953.

6. Gitlin LN. Good news for dementia care: caregiver interventions reduce behavioral symptoms in people with dementia and family distress. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):894-897.

7. Ho A, Collins SR, Davis K, Doty MM. A look at working-age caregivers roles, health concerns, and need for support. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2005;(854):1-12.

8. Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Smit F, et al. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? A randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30936.

9. Kolomer S, Quinn ME, Steele K. Interdisciplinary health fairs for older adults and the value of interprofessional service learning. J Community Pract. 2010;18(2-3):267-279.

10. Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):130-143.

11. Quinn C, Toms G, Anderson D, Clare L. A review of self-management interventions for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;pii:0733464814566852.

1. Alzheimer’s Association. 2015 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(3)332-384.

2. Schulz R, Beach SR, Cook TB, Martire LM, Tomlinson JM, Monin JK. Predictors and consequences of perceived lack of choice in becoming an informal caregiver. Aging Ment Health. 2012;16(6):712-721.

3. Cooper C, Mukadam N, Katona C, et al; World Federation of Biological Psychiatry – Old Age Taskforce. Systematic review of the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions to improve quality of life of people with dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24(6):856-870.

4. Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: the Caregiver Health Effects Study. JAMA. 1991;282(23):2215-2219.

5. Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946-953.

6. Gitlin LN. Good news for dementia care: caregiver interventions reduce behavioral symptoms in people with dementia and family distress. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):894-897.

7. Ho A, Collins SR, Davis K, Doty MM. A look at working-age caregivers roles, health concerns, and need for support. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2005;(854):1-12.

8. Joling KJ, van Marwijk HWJ, Smit F, et al. Does a family meetings intervention prevent depression and anxiety in family caregivers of dementia patients? A randomized trial. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e30936.

9. Kolomer S, Quinn ME, Steele K. Interdisciplinary health fairs for older adults and the value of interprofessional service learning. J Community Pract. 2010;18(2-3):267-279.

10. Jensen M, Agbata IN, Canavan M, McCarthy G. Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2015;30(2):130-143.

11. Quinn C, Toms G, Anderson D, Clare L. A review of self-management interventions for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. J Appl Gerontol. 2015;pii:0733464814566852.

Development and Evaluation of a Geriatric Mood Management Program

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

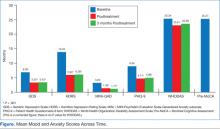

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Blow FC, Owen RE. Specialty care for veterans with depression in the VHA 2002 national registry report. Ann Arbor, MI: VHA Health Services Research and Development; 2003.

2. Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1554-1562.

3. Stanley MA, Roberts RE, Bourland SL, Novy DM. Anxiety disorders among older primary care patients. J Clin Geropsychology. 2001;7(2):105-116.

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193-204.

6. Pérés K, Jagger C, Matthews FE; MRC CFAS. Impact of late-life self-reported emotional problems on disability-free life expectancy: Results from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):643-649.

7. Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276-1282.

8. Small GW. Treatment of geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):32-42.

9. Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans health administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49-52.

10. Mavandadi S, Klaus JR, Oslin DW. Age group differences among veterans enrolled in a clinical service for behavioral health issues in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):205-214.

11. Lindley S, Cacciapaglia H, Noronha D, Carlson E, Schatzberg A. Monitoring mental health treatment acceptance and initial treatment adherence in veterans: Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom versus other veterans of other eras. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1208:104-113.

12. American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):236-260.

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Blow FC, Owen RE. Specialty care for veterans with depression in the VHA 2002 national registry report. Ann Arbor, MI: VHA Health Services Research and Development; 2003.

2. Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1554-1562.

3. Stanley MA, Roberts RE, Bourland SL, Novy DM. Anxiety disorders among older primary care patients. J Clin Geropsychology. 2001;7(2):105-116.

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193-204.

6. Pérés K, Jagger C, Matthews FE; MRC CFAS. Impact of late-life self-reported emotional problems on disability-free life expectancy: Results from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):643-649.

7. Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276-1282.

8. Small GW. Treatment of geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):32-42.

9. Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans health administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49-52.