User login

“We’ve Learned It’s a Medical Illness, Not a Moral Choice”: Qualitative Study of the Effects of a Multicomponent Addiction Intervention on Hospital Providers’ Attitudes and Experiences

Substance use disorders (SUD) represent a national epidemic with death rates exceeding those of HIV at its peak.1 Hospitals are increasingly filled with people suffering from medical complications of addiction.2,3 While the US health system spends billions of dollars annually on hospital care for medical problems resulting from SUD,4 most hospitals lack expertise or care systems to directly address SUD or connect people to treatment after discharge. 5,6

Patients with SUD often feel stigmatized in healthcare settings and want providers who understand SUD and how to treat it.7 Providers feel underprepared8 and commonly have negative attitudes toward patients with SUD.9,10 Caring for patients can be a source of resentment, dissatisfaction, and burnout.9 Such negative attitudes can adversely affect patient care. Studies show that patients who perceive discrimination by providers are less likely to complete treatment11 and providers’ negative attitudes may disempower patients.9

Evaluations of hospital interventions for adults with SUD focus primarily on patient-level outcomes of SUD severity,12 healthcare utilization,13 and treatment engagement.14,15 Little is known about how such interventions can affect interprofessional providers’ attitudes and experiences, or how systems-level interventions influence hospital culture.16

We performed a qualitative study of multidisciplinary hospital providers to 1) understand the challenges that hospital providers face in managing care for patients with SUD, and 2) explore how integrating SUD treatment in a hospital setting affects providers’ attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of the care environment. This study was part of a formative evaluation of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT). IMPACT includes a hospital-based, interprofessional addiction medicine consultation service and rapid-access pathways to community addiction care after hospitalization.17. IMPACT is an intensive intervention that includes SUD assessments, withdrawal management, medications for addiction (eg, methadone, buprenorphine induction), counseling and behavioral SUD treatment, peer engagement and support, and linkages to community-based addiction care. We described the rationale and design of IMPACT in earlier publications.7,17

METHODS

Setting

We conducted in-person interviews and focus groups (FGs) with interprofessional hospital providers at a single urban academic medical center between February and July 2016, six months after starting IMPACT implementation. Oregon Health and Science University’s (OHSU) institutional review board approved the protocol.

Participants

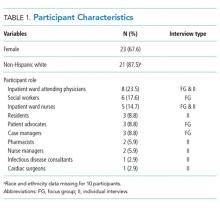

We conducted 12 individual informant interviews (IIs) and 6 (FGs) (each comprising 3-6 participants) with a wide range of providers, including physicians, nurses, social workers, residents, patient advocates, case managers, and pharmacists. In total, 34 providers participated. We used purposive sampling to choose participants with experience both caring for patients with SUD and with exposure to IMPACT. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Data Collection

We employed 2 different types of interviews. In situations where multiple providers occupied a similar role (eg, social workers), we chose to use a focus group format to elicit a range of perspectives and experiences through participant interaction.18 We conducted individual interviews to gain input from key informants who had unique roles in the program (eg, a cardiac surgeon) and to include providers who would otherwise be unable to participate due to scheduling barriers (eg, residents). We interviewed all participants using a semi-structured interview guide that was developed by an interdisciplinary team, including expert qualitative researchers, IMPACT clinical team members, and other OHSU clinicians (Appendix A). An interviewer who was not a part of the IMPACT clinical team asked all participants about their experience caring for patients with SUD, their experience with IMPACT, and how they might improve care. FGs lasted between 41-57 minutes, and individual key informant interviews lasted between 11-38 minutes. We ended recruitment after reaching theme saturation. Our goal was to achieve saturation across the sample as a whole and not within distinct participant groups. We noted if certain themes were more salient for 1 particular group. We audio-recorded all interviews and FGs. Recordings were transcribed, de-identified, and transferred to ATLAS.ti for data analysis.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using an inductive approach at the semantic level.19 Using an iterative process, we generated a preliminary coding schema after reviewing an initial selection of transcripts. Coders then independently coded transcripts and met in dyads to both discuss and reconcile codes, and resolve any discrepancies through discussion until reaching a consensus. One coder (DC) coded all transcripts; 3 coders (EP, SPP, MR) divided the transcripts evenly. All authors met periodically to discuss codebook revisions and emergent themes. We identified themes that represented patterns, had meaning to study participants, and captured important findings related to our research questions.19

As expected, the style of IIs differed from that of FGs and informants were able to provide information specific to their roles. Overall, the information provided by IIs was complementary to that of FGs and helped triangulate findings. Thus, we combined them in the results.18

RESULTS

We organized our findings into 3 main groupings, including (1) care before IMPACT, (2) care with IMPACT, and (3) perceived limitations of IMPACT. We included a table (Table 2) with additional quotations, beyond those in the body of the results, to support emergent themes described below.

Care before IMPACT

Providers felt hospitalization did not address addiction for many reasons, including ethical and legal concerns, medical knowledge gaps, and lack of treatment options.

Before IMPACT, many participants noted that hospitalization ignored or avoided addressing addiction, leading to a chaotic care environment that adversely affected patient care and provider experience. As one social worker stated, “prior to IMPACT we provided assessments, and we provided resources. But we didn’t address addiction.”

Providers cited multiple explanations for this, including the common misperception that using methadone to treat withdrawal violated federal regulations, and concerns about the ethicality of using opioids in patients with SUD. Across disciplines, providers described a “huge knowledge gap” and little confidence in addressing withdrawal, complex chronic pain, medications for addiction, and challenging patient behaviors. Providers also described limited expertise and scarce treatment options as a deterrent. As one attending reflected, “I would ask those questions [about SUD] before, but then … I had the information, but I couldn’t do anything with it.”

Providers felt the failure to address SUD adversely affected patient care, leading to untreated withdrawal, disruptive behaviors, and patients leaving against medical advice (AMA).

Participants across disciplines described wide variability in the medical management of SUD, particularly around the management of opioid withdrawal and pain, with some providers who “simply wouldn’t prescribe methadone or any opiates” and others who prescribed high doses without anticipating risks. As one attending recalled:

“You would see this pattern, especially in the intravenous drug-using population: left AMA, left AMA, left AMA … nine times out of ten, nobody was dealing with the fact that they were gonna go into withdrawal.”

Respondents recalled that disruptive behaviors from patients’ active use or withdrawal frequently threatened safety; imposed a tremendous burden on staff time and morale; and were a consistent source of providers’ distress. As one patient advocate explained:

“[Providers] get called to the unit because the person is yelling and throwing things or comes back after being gone for a long period and appears impaired … it often blows up, and they get discharged or they leave against medical advice or they go out and don’t come back. We don’t really know what happened to them, and they’re vulnerable. And the staff are vulnerable. And other patients are distressed by the disruption and commotion.”

Absent standards and systems to address SUD, providers felt they were “left to their own,” resulting in a reactive and chaotic care environment.

Providers noted inconsistent rules and policies regarding smoke breaks, room searches, and visitors. As a result, care felt “reckless and risky” and led to a “nonalliance” across disciplines. Providers frequently described inconsistent and loose expectations until an event -- often active use – triggered an ad hoc ratcheting up of the rules, damaging patient-provider relationships and limiting providers’ ability to provide medical care. Facing these conflicts, “staff gets escalated, and everybody gets kind of spun up.” As one attending reflected:

“I could not get any sort of engagement even in just her medical issues … I was trying to talk to her and educate her about heart failure and salt intake and food intake, but every time I walked in the room … I’d have to come in and be like, ‘your UDS [urine drug screen] was positive again, so here’s the changes to your behavioral plan, and OK, let’s talk about your heart failure …’ At that point, the relationship had completely disintegrated until it was very nonproductive.”

Providers described widespread “moral distress,” burnout, and feelings of futility before IMPACT.

Consequently, providers felt that caring for people with SUD was “very emotionally draining and very time consuming.” As one patient advocate described:

“We’ve been watching staff try to manage these patients for years without the experts and the resources and the skills that they need … As a result, there was a crescendo effect of moral distress, and [staff] bring in all of their past experiences which influence the interaction … Some staff are very skilled, but you also saw some really punitive responses.”

Many felt that providing intensive medical care without addressing people’s underlying SUD was a waste of time and resources. As one cardiac surgeon reflected:

“[Patients] ended up either dead or reinfected. Nobody wanted to do stuff because we felt it was futile. Well, of course, it’s futile …. you’re basically trying to fix the symptoms. It’s like having a leaky roof and just running around with a bunch of buckets, which is like surgery. You gotta fix the roof…otherwise they will continue to inject bacteria into their bodies.”

Care with IMPACT:

Providers felt integrating hospital-based systems to address SUD legitimized addiction as a treatable disease.

Participants described IMPACT as a “sea change” that “completely reframes” addiction as “a medical condition that actually has a treatment.” As one social worker observed, “when it’s somebody in a white coat with expertise who’s talking to another doctor it really can shift mindsets in an amazing way.” Others echoed this, stating that an addiction team “legitimized the fact that this is an actual disease that we need to treat - and a failure to treat it is a failure to be a good doctor.”

Providers felt that by addressing addiction directly, “IMPACT elevated the consciousness of providers and nurses … that substance use disorders are brain disorders and not bad behavior.” They described that this legitimization, combined with seeing firsthand the stabilizing effects of medications for addiction, allowed providers to understand SUD as a chronic disease, and not a moral failing.

Providers felt IMPACT improved patient engagement and humanized care by treating withdrawal, directly communicating about SUD, and modeling compassionate care.

Providers noted that treating withdrawal had a dramatic effect on patient engagement and care. One surgeon explained, “by managing their opioid dependence and other substance abuse issues … it’s easier for the staff to take care of them, it’s safer, and the patients feel better taken care of because the staff will engage with them.” Many noted that conflict-ridden “conversations were able to go to the side, and we were able to talk about other things to build rapport.” Others noted that this shift felt like “more productive time.”

In addition, providers repeatedly emphasized that having clear hospital standards and a process to engage patients “really helps … establish rapport with patients: ‘This is how we work this. These are your boundaries. And this is what will happen if you push those boundaries.’ There it is.” Providers attributed improved patient-provider communication to “frank conversation,” “the right amount of empathy,” and a less judgmental environment. As one attending described, “I don’t know if it gives them a voice or allows us to hear them better … but something’s happening with communication.”

Many participants highlighted that IMPACT modeled compassionate bedside interactions, exposed the role of trauma in many patients’ lives, and helped providers see SUD as a disease spectrum. One attending noted that to “actually appreciate the subtleties – just the severity of the disorder – has been powerful.” One resident said:

“There’s definitely a lot of stigma around patients with use disorders that probably shows itself in subtle ways throughout their hospitalization. I think IMPACT does a good job … keeping the patient in the center and keeping their use disorder contextualized in the greater person … [IMPACT] role models bedside interactions and how to treat people like humans.”

Providers valued post-hospital SUD treatment pathways.

Providers valued previously nonexistent post-hospital SUD treatment pathways, stating “this relationship with [community treatment] … it’s like an answer to prayers,” and “this isn’t just like we’re being nicer.” One attending described:

“Starting them on [methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone] and then making the next step in the outpatient world happen has been huge. That transition is so critical … that’s been probably the biggest impact.”

Providers felt relief after IMPACT implementation.

Providers felt that by addressing SUD treatment gaps and providing addiction expertise, IMPACT helped alleviate the previously widespread feelings of “moral distress.” One resident explained “having [IMPACT] as a lifeline, it just feels so good.” As an infectious disease consultant noted, “it makes people more open to treating people if they don’t feel isolated and out of their depth.” Others noted that IMPACT supported better multidisciplinary collaboration, which “reduced a lot of tension between the teams.” One nurse summarized:

“I think you feel more empowered when you’ve got the right medication, … the knowledge, and you feel like you have the resources. You actually feel like you’re making a difference.”

Respondents acknowledged that even with IMPACT, some patients leave AMA or relapse. However, by understanding addiction as a relapsing and remitting disease, providers reconceptualized “success,” further reducing feelings of emotional burnout and stress: “there will be ups and downs, it’s not gonna be a straight linear success.” One case manager reflected,

“Maybe that’s part of the nature of the illness, you progress, and then you kind of hold your breath and then it slips again … at least with IMPACT at the table I can say we’ve done the best we can for this person.”

Perceived limitations of IMPACT:

Providers noted several key limitations of IMPACT, including that hospital-based interventions do not address poverty and have limited ability to address socioeconomic determinants such as “social support, … housing, or nutrition.” Providers also felt that IMPACT had limited ability to alleviate patients’ feelings of boredom and isolation associated with prolonged hospitalization, and that IMPACT had limited effectiveness for highly ambivalent patients (Table 2).

Finally, while many described increased confidence managing SUD after working with IMPACT, others cautioned against deferring too much to specialists. As one resident doctor said:

“We shouldn’t forget that all providers should know how to handle some form of people with addiction … I just don’t want it to be like, ‘oh, well, no, I don’t need to think about this … because we have an addiction specialist.’”

Participants across disciplines repeatedly suggested formal, ongoing initiatives to educate and train providers to manage SUD independently.

DISCUSSION

This study explores provider perspectives on care for hospitalized adults with SUD. Before IMPACT, providers felt care was chaotic, unsafe, and frustrating. Providers perceived variable care quality, resulting in untreated withdrawal, inconsistent care plans, and poor patient outcomes, leading to widespread “moral distress” and feelings of futility among providers. Yet this experience was not inevitable. Providers described that a hospital-based intervention to treat SUD reframed addiction as a treatable chronic disease, transformed culture, and improved patient care and provider experience.

Our findings are consistent with and build on previous research in several ways. First, widespread anxiety and difficulty managing patients with SUD was not unique to our hospital. In a systematic review, van Boekel and colleagues describe that healthcare providers perceived violence, manipulation, and poor motivation as factors impeding care for patients with SUD.9 Our study demonstrates the resulting feelings of powerlessness and frustration may be alleviated through an intervention that provides SUD care.

Second, our study is consistent with a recent survey-based study by Wakeman and colleagues that found that a hospital-based SUD intervention improved providers’ feelings of preparedness and satisfaction.20 Our study provides a rich qualitative description and elucidates mechanisms by which such interventions may work.

The finding that a hospital-based SUD intervention can shift providers’ views of addiction is important. Earlier studies have shown that providers who perceive addiction as a choice are more likely to have negative attitudes toward people with SUD.11 While our intervention did not provide formal education aimed at changing attitudes, participants reported that seeing firsthand effects of treatment on patient behaviors was a powerful tool that radically shifted providers’ understanding and reduced stigma.

Stigma can occur at both individual and organizational levels. Structural stigma refers to practices, policies, and norms of institutions that exclude needs of a particular group.21 The absence of systems to address SUD sends a message to both patients and providers that addiction is a not a treatable or worthy disease. IMPACT was in and of itself a systems-level intervention; by creating a consultation service, hospital-wide policies, and pathways to care after hospitalization, IMPACT ‘legitimized’ SUD and reduced institutional stigma.

Several studies have shown the feasibility and effectiveness of starting medications for addiction (MAT) in the hospital.13-15 Our study builds on this work by highlighting systems-level elements valued by providers. These elements may be important to support and scale widespread adoption of MAT in hospitals. Specifically, providers felt that IMPACT’s attention to hospital policies, use of addiction medicine specialists, and direct linkages to outpatient SUD treatment proved instrumental in shifting care systems.

Our study has several limitations. As a single-site study, our goal was not generalizability, but transferability. As such, we aimed to obtain rich, in-depth information that can inform implementation of similar efforts. Because our study was conducted after the implementation of IMPACT, providers’ perspectives on care before IMPACT may have been influenced by the intervention. However, this also strengthens our findings by allowing participants the opportunity for insights under a different system. It likely leads to distinct findings compared to what we might have uncovered in a pre-post study. While respondents noted perceived limitations of IMPACT, there were few instances of negative remarks in the data we collected. It is possible that providers with more negative interpretations chose not to participate in interviews; however, we elicited wide viewpoints and encouraged participants to share both strengths and weaknesses. Finally, IMPACT implementation depends on regional as well as local factors such as Medicaid expansion, community treatment resources, and the existence of addiction medicine expertise that will differ across settings.

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. For clinical practice, our findings highlight the importance of treating withdrawal to address challenging patient behaviors and the value of integrating MAT into the hospital setting. Our findings also underscore the role of expert consultation for addiction. Importantly, our results emphasize that reframing SUD as a brain disease can have significant implications for clinical care and providers’ well-being. Provider distress is not inevitable and can change with the right support and systems.

At the hospital and health systems level, our findings suggest that hospitals can and should address SUD. This may include forming interprofessional teams with SUD expertise, providing standardized guidelines for addiction care such as patient safety plans and methadone policies, and creating rapid-access pathways to outpatient SUD care. By addressing SUD, hospitals may simultaneously improve care and reduce provider burnout. Providers’ important concerns about shifting SUD treatment to a specialty team and their discomfort managing SUD pre-IMPACT suggest the need to integrate SUD education across all levels of interprofessional education. Furthermore, provider concerns that IMPACT has limited ability to engage ambivalent patients underscores the need for hospital-based approaches that emphasize harm reduction strategies.

As the SUD epidemic worsens, SUD-related hospitalizations are skyrocketing, and people are dying at unprecedented rates.2,3 Many efforts to address SUD have been in primary care or community settings. While important, many people with SUD are unable or unlikely to seek primary care. 22 Hospitals need a workforce and systems that can address both the physical and behavioral health needs of this population. By implementing SUD improvements, hospitals can support staff and reduce burnout, better engage patients, improve care, and reduce stigma from this devastating disease

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Rossen L, Bastian B, Warner M, Khan D, Chong Y. Drug poisoning mortality: United States, 1999-2015. 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/drug-poisoning-mortality/. Accessed 7-11, 2017.

2. Tedesco D, Asch SM, Curtin C, et al. Opioid abuse and poisoning: trends in inpatient and emergency department discharges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1748-1753. http:// doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0260. PubMed

3. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barrett ML, Steiner CA, Bailey MK, O’Malley L. Statistical Brief #219: Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits by State, 2009-2014. 2017; https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp?utm_source=AHRQ&utm_medium=EN-2&utm_term=&utm_content=2&utm_campaign=AHRQ_EN12_20_2016. Accessed July 11, 2017. PubMed

4. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. http:// doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424. PubMed

5. Infectious Diseases Society of America Emerging Infections Network. Report for Query: ‘Injection Drug Use (IDU) and Infectious Disease Practice’. 2017; https://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/Research/EIN/FinalReport_IDUandID.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2017.

6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481-485. http:// doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024. PubMed

7. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an Experience, a Life Learning Experience”: A qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4. PubMed

8. Wakeman SE, Pham-Kanter G, Donelan K. Attitudes, practices, and preparedness to care for patients with substance use disorder: Results from a survey of general internists. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):635-641. http:// doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2016.1187240. PubMed

9. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. http:// doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 PubMed

10. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327-333. http:// doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10625.x. PubMed

11. Brener L, Von Hippel W, Kippax S, Preacher KJ. The role of physician and nurse attitudes in the health care of injecting drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(7-8):1007-1018. http:// doi.org/10.3109/10826081003659543. PubMed

12. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z. PubMed

13. Wei J, Defries T, Lozada M, Young N, Huen W, Tulsky J. An inpatient treatment and discharge planning protocol for alcohol dependence: efficacy in reducing 30-day readmissions and emergency department visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):365-370. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2968-9. PubMed

14. Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. http:// doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556. PubMed

15. Shanahan CW, Beers D, Alford DP, Brigandi E, Samet JH. A transitional opioid program to engage hospitalized drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):803-808. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1311-3. PubMed

16. Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F, Baillie N, Schaafsma ME, Eccles MP. The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):33. http:// doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-33. PubMed

17. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the improving addiction care team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. http:// doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736. PubMed

18. Lambert SD, Loiselle CG. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(2):228-237. http:// doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x. PubMed

19. Braun VC, Victoria. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3:25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

20. Wakeman SE, Kanter GP, Donelan K. Institutional substance use disorder intervention improves general internist preparedness, attitudes, and clinical practice. J Addict Med. 2017;11(4):308-314. http:// doi.org/10.1097/ADM.0000000000000314. PubMed

21. Paterson B, Hirsch G, Andres K. Structural factors that promote stigmatization of drug users with hepatitis C in hospital emergency departments. Int J Drug Policy. 2013;24(5):471-478. http:// doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2013.01.008 PubMed

22. Ross LE, Vigod S, Wishart J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to primary care for people with mental health and/or substance use issues: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16:135. http:// doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0353-3. PubMed

Substance use disorders (SUD) represent a national epidemic with death rates exceeding those of HIV at its peak.1 Hospitals are increasingly filled with people suffering from medical complications of addiction.2,3 While the US health system spends billions of dollars annually on hospital care for medical problems resulting from SUD,4 most hospitals lack expertise or care systems to directly address SUD or connect people to treatment after discharge. 5,6

Patients with SUD often feel stigmatized in healthcare settings and want providers who understand SUD and how to treat it.7 Providers feel underprepared8 and commonly have negative attitudes toward patients with SUD.9,10 Caring for patients can be a source of resentment, dissatisfaction, and burnout.9 Such negative attitudes can adversely affect patient care. Studies show that patients who perceive discrimination by providers are less likely to complete treatment11 and providers’ negative attitudes may disempower patients.9

Evaluations of hospital interventions for adults with SUD focus primarily on patient-level outcomes of SUD severity,12 healthcare utilization,13 and treatment engagement.14,15 Little is known about how such interventions can affect interprofessional providers’ attitudes and experiences, or how systems-level interventions influence hospital culture.16

We performed a qualitative study of multidisciplinary hospital providers to 1) understand the challenges that hospital providers face in managing care for patients with SUD, and 2) explore how integrating SUD treatment in a hospital setting affects providers’ attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of the care environment. This study was part of a formative evaluation of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT). IMPACT includes a hospital-based, interprofessional addiction medicine consultation service and rapid-access pathways to community addiction care after hospitalization.17. IMPACT is an intensive intervention that includes SUD assessments, withdrawal management, medications for addiction (eg, methadone, buprenorphine induction), counseling and behavioral SUD treatment, peer engagement and support, and linkages to community-based addiction care. We described the rationale and design of IMPACT in earlier publications.7,17

METHODS

Setting

We conducted in-person interviews and focus groups (FGs) with interprofessional hospital providers at a single urban academic medical center between February and July 2016, six months after starting IMPACT implementation. Oregon Health and Science University’s (OHSU) institutional review board approved the protocol.

Participants

We conducted 12 individual informant interviews (IIs) and 6 (FGs) (each comprising 3-6 participants) with a wide range of providers, including physicians, nurses, social workers, residents, patient advocates, case managers, and pharmacists. In total, 34 providers participated. We used purposive sampling to choose participants with experience both caring for patients with SUD and with exposure to IMPACT. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Data Collection

We employed 2 different types of interviews. In situations where multiple providers occupied a similar role (eg, social workers), we chose to use a focus group format to elicit a range of perspectives and experiences through participant interaction.18 We conducted individual interviews to gain input from key informants who had unique roles in the program (eg, a cardiac surgeon) and to include providers who would otherwise be unable to participate due to scheduling barriers (eg, residents). We interviewed all participants using a semi-structured interview guide that was developed by an interdisciplinary team, including expert qualitative researchers, IMPACT clinical team members, and other OHSU clinicians (Appendix A). An interviewer who was not a part of the IMPACT clinical team asked all participants about their experience caring for patients with SUD, their experience with IMPACT, and how they might improve care. FGs lasted between 41-57 minutes, and individual key informant interviews lasted between 11-38 minutes. We ended recruitment after reaching theme saturation. Our goal was to achieve saturation across the sample as a whole and not within distinct participant groups. We noted if certain themes were more salient for 1 particular group. We audio-recorded all interviews and FGs. Recordings were transcribed, de-identified, and transferred to ATLAS.ti for data analysis.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using an inductive approach at the semantic level.19 Using an iterative process, we generated a preliminary coding schema after reviewing an initial selection of transcripts. Coders then independently coded transcripts and met in dyads to both discuss and reconcile codes, and resolve any discrepancies through discussion until reaching a consensus. One coder (DC) coded all transcripts; 3 coders (EP, SPP, MR) divided the transcripts evenly. All authors met periodically to discuss codebook revisions and emergent themes. We identified themes that represented patterns, had meaning to study participants, and captured important findings related to our research questions.19

As expected, the style of IIs differed from that of FGs and informants were able to provide information specific to their roles. Overall, the information provided by IIs was complementary to that of FGs and helped triangulate findings. Thus, we combined them in the results.18

RESULTS

We organized our findings into 3 main groupings, including (1) care before IMPACT, (2) care with IMPACT, and (3) perceived limitations of IMPACT. We included a table (Table 2) with additional quotations, beyond those in the body of the results, to support emergent themes described below.

Care before IMPACT

Providers felt hospitalization did not address addiction for many reasons, including ethical and legal concerns, medical knowledge gaps, and lack of treatment options.

Before IMPACT, many participants noted that hospitalization ignored or avoided addressing addiction, leading to a chaotic care environment that adversely affected patient care and provider experience. As one social worker stated, “prior to IMPACT we provided assessments, and we provided resources. But we didn’t address addiction.”

Providers cited multiple explanations for this, including the common misperception that using methadone to treat withdrawal violated federal regulations, and concerns about the ethicality of using opioids in patients with SUD. Across disciplines, providers described a “huge knowledge gap” and little confidence in addressing withdrawal, complex chronic pain, medications for addiction, and challenging patient behaviors. Providers also described limited expertise and scarce treatment options as a deterrent. As one attending reflected, “I would ask those questions [about SUD] before, but then … I had the information, but I couldn’t do anything with it.”

Providers felt the failure to address SUD adversely affected patient care, leading to untreated withdrawal, disruptive behaviors, and patients leaving against medical advice (AMA).

Participants across disciplines described wide variability in the medical management of SUD, particularly around the management of opioid withdrawal and pain, with some providers who “simply wouldn’t prescribe methadone or any opiates” and others who prescribed high doses without anticipating risks. As one attending recalled:

“You would see this pattern, especially in the intravenous drug-using population: left AMA, left AMA, left AMA … nine times out of ten, nobody was dealing with the fact that they were gonna go into withdrawal.”

Respondents recalled that disruptive behaviors from patients’ active use or withdrawal frequently threatened safety; imposed a tremendous burden on staff time and morale; and were a consistent source of providers’ distress. As one patient advocate explained:

“[Providers] get called to the unit because the person is yelling and throwing things or comes back after being gone for a long period and appears impaired … it often blows up, and they get discharged or they leave against medical advice or they go out and don’t come back. We don’t really know what happened to them, and they’re vulnerable. And the staff are vulnerable. And other patients are distressed by the disruption and commotion.”

Absent standards and systems to address SUD, providers felt they were “left to their own,” resulting in a reactive and chaotic care environment.

Providers noted inconsistent rules and policies regarding smoke breaks, room searches, and visitors. As a result, care felt “reckless and risky” and led to a “nonalliance” across disciplines. Providers frequently described inconsistent and loose expectations until an event -- often active use – triggered an ad hoc ratcheting up of the rules, damaging patient-provider relationships and limiting providers’ ability to provide medical care. Facing these conflicts, “staff gets escalated, and everybody gets kind of spun up.” As one attending reflected:

“I could not get any sort of engagement even in just her medical issues … I was trying to talk to her and educate her about heart failure and salt intake and food intake, but every time I walked in the room … I’d have to come in and be like, ‘your UDS [urine drug screen] was positive again, so here’s the changes to your behavioral plan, and OK, let’s talk about your heart failure …’ At that point, the relationship had completely disintegrated until it was very nonproductive.”

Providers described widespread “moral distress,” burnout, and feelings of futility before IMPACT.

Consequently, providers felt that caring for people with SUD was “very emotionally draining and very time consuming.” As one patient advocate described:

“We’ve been watching staff try to manage these patients for years without the experts and the resources and the skills that they need … As a result, there was a crescendo effect of moral distress, and [staff] bring in all of their past experiences which influence the interaction … Some staff are very skilled, but you also saw some really punitive responses.”

Many felt that providing intensive medical care without addressing people’s underlying SUD was a waste of time and resources. As one cardiac surgeon reflected:

“[Patients] ended up either dead or reinfected. Nobody wanted to do stuff because we felt it was futile. Well, of course, it’s futile …. you’re basically trying to fix the symptoms. It’s like having a leaky roof and just running around with a bunch of buckets, which is like surgery. You gotta fix the roof…otherwise they will continue to inject bacteria into their bodies.”

Care with IMPACT:

Providers felt integrating hospital-based systems to address SUD legitimized addiction as a treatable disease.

Participants described IMPACT as a “sea change” that “completely reframes” addiction as “a medical condition that actually has a treatment.” As one social worker observed, “when it’s somebody in a white coat with expertise who’s talking to another doctor it really can shift mindsets in an amazing way.” Others echoed this, stating that an addiction team “legitimized the fact that this is an actual disease that we need to treat - and a failure to treat it is a failure to be a good doctor.”

Providers felt that by addressing addiction directly, “IMPACT elevated the consciousness of providers and nurses … that substance use disorders are brain disorders and not bad behavior.” They described that this legitimization, combined with seeing firsthand the stabilizing effects of medications for addiction, allowed providers to understand SUD as a chronic disease, and not a moral failing.

Providers felt IMPACT improved patient engagement and humanized care by treating withdrawal, directly communicating about SUD, and modeling compassionate care.

Providers noted that treating withdrawal had a dramatic effect on patient engagement and care. One surgeon explained, “by managing their opioid dependence and other substance abuse issues … it’s easier for the staff to take care of them, it’s safer, and the patients feel better taken care of because the staff will engage with them.” Many noted that conflict-ridden “conversations were able to go to the side, and we were able to talk about other things to build rapport.” Others noted that this shift felt like “more productive time.”

In addition, providers repeatedly emphasized that having clear hospital standards and a process to engage patients “really helps … establish rapport with patients: ‘This is how we work this. These are your boundaries. And this is what will happen if you push those boundaries.’ There it is.” Providers attributed improved patient-provider communication to “frank conversation,” “the right amount of empathy,” and a less judgmental environment. As one attending described, “I don’t know if it gives them a voice or allows us to hear them better … but something’s happening with communication.”

Many participants highlighted that IMPACT modeled compassionate bedside interactions, exposed the role of trauma in many patients’ lives, and helped providers see SUD as a disease spectrum. One attending noted that to “actually appreciate the subtleties – just the severity of the disorder – has been powerful.” One resident said:

“There’s definitely a lot of stigma around patients with use disorders that probably shows itself in subtle ways throughout their hospitalization. I think IMPACT does a good job … keeping the patient in the center and keeping their use disorder contextualized in the greater person … [IMPACT] role models bedside interactions and how to treat people like humans.”

Providers valued post-hospital SUD treatment pathways.

Providers valued previously nonexistent post-hospital SUD treatment pathways, stating “this relationship with [community treatment] … it’s like an answer to prayers,” and “this isn’t just like we’re being nicer.” One attending described:

“Starting them on [methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone] and then making the next step in the outpatient world happen has been huge. That transition is so critical … that’s been probably the biggest impact.”

Providers felt relief after IMPACT implementation.

Providers felt that by addressing SUD treatment gaps and providing addiction expertise, IMPACT helped alleviate the previously widespread feelings of “moral distress.” One resident explained “having [IMPACT] as a lifeline, it just feels so good.” As an infectious disease consultant noted, “it makes people more open to treating people if they don’t feel isolated and out of their depth.” Others noted that IMPACT supported better multidisciplinary collaboration, which “reduced a lot of tension between the teams.” One nurse summarized:

“I think you feel more empowered when you’ve got the right medication, … the knowledge, and you feel like you have the resources. You actually feel like you’re making a difference.”

Respondents acknowledged that even with IMPACT, some patients leave AMA or relapse. However, by understanding addiction as a relapsing and remitting disease, providers reconceptualized “success,” further reducing feelings of emotional burnout and stress: “there will be ups and downs, it’s not gonna be a straight linear success.” One case manager reflected,

“Maybe that’s part of the nature of the illness, you progress, and then you kind of hold your breath and then it slips again … at least with IMPACT at the table I can say we’ve done the best we can for this person.”

Perceived limitations of IMPACT:

Providers noted several key limitations of IMPACT, including that hospital-based interventions do not address poverty and have limited ability to address socioeconomic determinants such as “social support, … housing, or nutrition.” Providers also felt that IMPACT had limited ability to alleviate patients’ feelings of boredom and isolation associated with prolonged hospitalization, and that IMPACT had limited effectiveness for highly ambivalent patients (Table 2).

Finally, while many described increased confidence managing SUD after working with IMPACT, others cautioned against deferring too much to specialists. As one resident doctor said:

“We shouldn’t forget that all providers should know how to handle some form of people with addiction … I just don’t want it to be like, ‘oh, well, no, I don’t need to think about this … because we have an addiction specialist.’”

Participants across disciplines repeatedly suggested formal, ongoing initiatives to educate and train providers to manage SUD independently.

DISCUSSION

This study explores provider perspectives on care for hospitalized adults with SUD. Before IMPACT, providers felt care was chaotic, unsafe, and frustrating. Providers perceived variable care quality, resulting in untreated withdrawal, inconsistent care plans, and poor patient outcomes, leading to widespread “moral distress” and feelings of futility among providers. Yet this experience was not inevitable. Providers described that a hospital-based intervention to treat SUD reframed addiction as a treatable chronic disease, transformed culture, and improved patient care and provider experience.

Our findings are consistent with and build on previous research in several ways. First, widespread anxiety and difficulty managing patients with SUD was not unique to our hospital. In a systematic review, van Boekel and colleagues describe that healthcare providers perceived violence, manipulation, and poor motivation as factors impeding care for patients with SUD.9 Our study demonstrates the resulting feelings of powerlessness and frustration may be alleviated through an intervention that provides SUD care.

Second, our study is consistent with a recent survey-based study by Wakeman and colleagues that found that a hospital-based SUD intervention improved providers’ feelings of preparedness and satisfaction.20 Our study provides a rich qualitative description and elucidates mechanisms by which such interventions may work.

The finding that a hospital-based SUD intervention can shift providers’ views of addiction is important. Earlier studies have shown that providers who perceive addiction as a choice are more likely to have negative attitudes toward people with SUD.11 While our intervention did not provide formal education aimed at changing attitudes, participants reported that seeing firsthand effects of treatment on patient behaviors was a powerful tool that radically shifted providers’ understanding and reduced stigma.

Stigma can occur at both individual and organizational levels. Structural stigma refers to practices, policies, and norms of institutions that exclude needs of a particular group.21 The absence of systems to address SUD sends a message to both patients and providers that addiction is a not a treatable or worthy disease. IMPACT was in and of itself a systems-level intervention; by creating a consultation service, hospital-wide policies, and pathways to care after hospitalization, IMPACT ‘legitimized’ SUD and reduced institutional stigma.

Several studies have shown the feasibility and effectiveness of starting medications for addiction (MAT) in the hospital.13-15 Our study builds on this work by highlighting systems-level elements valued by providers. These elements may be important to support and scale widespread adoption of MAT in hospitals. Specifically, providers felt that IMPACT’s attention to hospital policies, use of addiction medicine specialists, and direct linkages to outpatient SUD treatment proved instrumental in shifting care systems.

Our study has several limitations. As a single-site study, our goal was not generalizability, but transferability. As such, we aimed to obtain rich, in-depth information that can inform implementation of similar efforts. Because our study was conducted after the implementation of IMPACT, providers’ perspectives on care before IMPACT may have been influenced by the intervention. However, this also strengthens our findings by allowing participants the opportunity for insights under a different system. It likely leads to distinct findings compared to what we might have uncovered in a pre-post study. While respondents noted perceived limitations of IMPACT, there were few instances of negative remarks in the data we collected. It is possible that providers with more negative interpretations chose not to participate in interviews; however, we elicited wide viewpoints and encouraged participants to share both strengths and weaknesses. Finally, IMPACT implementation depends on regional as well as local factors such as Medicaid expansion, community treatment resources, and the existence of addiction medicine expertise that will differ across settings.

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. For clinical practice, our findings highlight the importance of treating withdrawal to address challenging patient behaviors and the value of integrating MAT into the hospital setting. Our findings also underscore the role of expert consultation for addiction. Importantly, our results emphasize that reframing SUD as a brain disease can have significant implications for clinical care and providers’ well-being. Provider distress is not inevitable and can change with the right support and systems.

At the hospital and health systems level, our findings suggest that hospitals can and should address SUD. This may include forming interprofessional teams with SUD expertise, providing standardized guidelines for addiction care such as patient safety plans and methadone policies, and creating rapid-access pathways to outpatient SUD care. By addressing SUD, hospitals may simultaneously improve care and reduce provider burnout. Providers’ important concerns about shifting SUD treatment to a specialty team and their discomfort managing SUD pre-IMPACT suggest the need to integrate SUD education across all levels of interprofessional education. Furthermore, provider concerns that IMPACT has limited ability to engage ambivalent patients underscores the need for hospital-based approaches that emphasize harm reduction strategies.

As the SUD epidemic worsens, SUD-related hospitalizations are skyrocketing, and people are dying at unprecedented rates.2,3 Many efforts to address SUD have been in primary care or community settings. While important, many people with SUD are unable or unlikely to seek primary care. 22 Hospitals need a workforce and systems that can address both the physical and behavioral health needs of this population. By implementing SUD improvements, hospitals can support staff and reduce burnout, better engage patients, improve care, and reduce stigma from this devastating disease

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Substance use disorders (SUD) represent a national epidemic with death rates exceeding those of HIV at its peak.1 Hospitals are increasingly filled with people suffering from medical complications of addiction.2,3 While the US health system spends billions of dollars annually on hospital care for medical problems resulting from SUD,4 most hospitals lack expertise or care systems to directly address SUD or connect people to treatment after discharge. 5,6

Patients with SUD often feel stigmatized in healthcare settings and want providers who understand SUD and how to treat it.7 Providers feel underprepared8 and commonly have negative attitudes toward patients with SUD.9,10 Caring for patients can be a source of resentment, dissatisfaction, and burnout.9 Such negative attitudes can adversely affect patient care. Studies show that patients who perceive discrimination by providers are less likely to complete treatment11 and providers’ negative attitudes may disempower patients.9

Evaluations of hospital interventions for adults with SUD focus primarily on patient-level outcomes of SUD severity,12 healthcare utilization,13 and treatment engagement.14,15 Little is known about how such interventions can affect interprofessional providers’ attitudes and experiences, or how systems-level interventions influence hospital culture.16

We performed a qualitative study of multidisciplinary hospital providers to 1) understand the challenges that hospital providers face in managing care for patients with SUD, and 2) explore how integrating SUD treatment in a hospital setting affects providers’ attitudes, experiences, and perceptions of the care environment. This study was part of a formative evaluation of the Improving Addiction Care Team (IMPACT). IMPACT includes a hospital-based, interprofessional addiction medicine consultation service and rapid-access pathways to community addiction care after hospitalization.17. IMPACT is an intensive intervention that includes SUD assessments, withdrawal management, medications for addiction (eg, methadone, buprenorphine induction), counseling and behavioral SUD treatment, peer engagement and support, and linkages to community-based addiction care. We described the rationale and design of IMPACT in earlier publications.7,17

METHODS

Setting

We conducted in-person interviews and focus groups (FGs) with interprofessional hospital providers at a single urban academic medical center between February and July 2016, six months after starting IMPACT implementation. Oregon Health and Science University’s (OHSU) institutional review board approved the protocol.

Participants

We conducted 12 individual informant interviews (IIs) and 6 (FGs) (each comprising 3-6 participants) with a wide range of providers, including physicians, nurses, social workers, residents, patient advocates, case managers, and pharmacists. In total, 34 providers participated. We used purposive sampling to choose participants with experience both caring for patients with SUD and with exposure to IMPACT. Participant characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Data Collection

We employed 2 different types of interviews. In situations where multiple providers occupied a similar role (eg, social workers), we chose to use a focus group format to elicit a range of perspectives and experiences through participant interaction.18 We conducted individual interviews to gain input from key informants who had unique roles in the program (eg, a cardiac surgeon) and to include providers who would otherwise be unable to participate due to scheduling barriers (eg, residents). We interviewed all participants using a semi-structured interview guide that was developed by an interdisciplinary team, including expert qualitative researchers, IMPACT clinical team members, and other OHSU clinicians (Appendix A). An interviewer who was not a part of the IMPACT clinical team asked all participants about their experience caring for patients with SUD, their experience with IMPACT, and how they might improve care. FGs lasted between 41-57 minutes, and individual key informant interviews lasted between 11-38 minutes. We ended recruitment after reaching theme saturation. Our goal was to achieve saturation across the sample as a whole and not within distinct participant groups. We noted if certain themes were more salient for 1 particular group. We audio-recorded all interviews and FGs. Recordings were transcribed, de-identified, and transferred to ATLAS.ti for data analysis.

Analysis

We conducted a thematic analysis using an inductive approach at the semantic level.19 Using an iterative process, we generated a preliminary coding schema after reviewing an initial selection of transcripts. Coders then independently coded transcripts and met in dyads to both discuss and reconcile codes, and resolve any discrepancies through discussion until reaching a consensus. One coder (DC) coded all transcripts; 3 coders (EP, SPP, MR) divided the transcripts evenly. All authors met periodically to discuss codebook revisions and emergent themes. We identified themes that represented patterns, had meaning to study participants, and captured important findings related to our research questions.19

As expected, the style of IIs differed from that of FGs and informants were able to provide information specific to their roles. Overall, the information provided by IIs was complementary to that of FGs and helped triangulate findings. Thus, we combined them in the results.18

RESULTS

We organized our findings into 3 main groupings, including (1) care before IMPACT, (2) care with IMPACT, and (3) perceived limitations of IMPACT. We included a table (Table 2) with additional quotations, beyond those in the body of the results, to support emergent themes described below.

Care before IMPACT

Providers felt hospitalization did not address addiction for many reasons, including ethical and legal concerns, medical knowledge gaps, and lack of treatment options.

Before IMPACT, many participants noted that hospitalization ignored or avoided addressing addiction, leading to a chaotic care environment that adversely affected patient care and provider experience. As one social worker stated, “prior to IMPACT we provided assessments, and we provided resources. But we didn’t address addiction.”

Providers cited multiple explanations for this, including the common misperception that using methadone to treat withdrawal violated federal regulations, and concerns about the ethicality of using opioids in patients with SUD. Across disciplines, providers described a “huge knowledge gap” and little confidence in addressing withdrawal, complex chronic pain, medications for addiction, and challenging patient behaviors. Providers also described limited expertise and scarce treatment options as a deterrent. As one attending reflected, “I would ask those questions [about SUD] before, but then … I had the information, but I couldn’t do anything with it.”

Providers felt the failure to address SUD adversely affected patient care, leading to untreated withdrawal, disruptive behaviors, and patients leaving against medical advice (AMA).

Participants across disciplines described wide variability in the medical management of SUD, particularly around the management of opioid withdrawal and pain, with some providers who “simply wouldn’t prescribe methadone or any opiates” and others who prescribed high doses without anticipating risks. As one attending recalled:

“You would see this pattern, especially in the intravenous drug-using population: left AMA, left AMA, left AMA … nine times out of ten, nobody was dealing with the fact that they were gonna go into withdrawal.”

Respondents recalled that disruptive behaviors from patients’ active use or withdrawal frequently threatened safety; imposed a tremendous burden on staff time and morale; and were a consistent source of providers’ distress. As one patient advocate explained:

“[Providers] get called to the unit because the person is yelling and throwing things or comes back after being gone for a long period and appears impaired … it often blows up, and they get discharged or they leave against medical advice or they go out and don’t come back. We don’t really know what happened to them, and they’re vulnerable. And the staff are vulnerable. And other patients are distressed by the disruption and commotion.”

Absent standards and systems to address SUD, providers felt they were “left to their own,” resulting in a reactive and chaotic care environment.

Providers noted inconsistent rules and policies regarding smoke breaks, room searches, and visitors. As a result, care felt “reckless and risky” and led to a “nonalliance” across disciplines. Providers frequently described inconsistent and loose expectations until an event -- often active use – triggered an ad hoc ratcheting up of the rules, damaging patient-provider relationships and limiting providers’ ability to provide medical care. Facing these conflicts, “staff gets escalated, and everybody gets kind of spun up.” As one attending reflected:

“I could not get any sort of engagement even in just her medical issues … I was trying to talk to her and educate her about heart failure and salt intake and food intake, but every time I walked in the room … I’d have to come in and be like, ‘your UDS [urine drug screen] was positive again, so here’s the changes to your behavioral plan, and OK, let’s talk about your heart failure …’ At that point, the relationship had completely disintegrated until it was very nonproductive.”

Providers described widespread “moral distress,” burnout, and feelings of futility before IMPACT.

Consequently, providers felt that caring for people with SUD was “very emotionally draining and very time consuming.” As one patient advocate described:

“We’ve been watching staff try to manage these patients for years without the experts and the resources and the skills that they need … As a result, there was a crescendo effect of moral distress, and [staff] bring in all of their past experiences which influence the interaction … Some staff are very skilled, but you also saw some really punitive responses.”

Many felt that providing intensive medical care without addressing people’s underlying SUD was a waste of time and resources. As one cardiac surgeon reflected:

“[Patients] ended up either dead or reinfected. Nobody wanted to do stuff because we felt it was futile. Well, of course, it’s futile …. you’re basically trying to fix the symptoms. It’s like having a leaky roof and just running around with a bunch of buckets, which is like surgery. You gotta fix the roof…otherwise they will continue to inject bacteria into their bodies.”

Care with IMPACT:

Providers felt integrating hospital-based systems to address SUD legitimized addiction as a treatable disease.

Participants described IMPACT as a “sea change” that “completely reframes” addiction as “a medical condition that actually has a treatment.” As one social worker observed, “when it’s somebody in a white coat with expertise who’s talking to another doctor it really can shift mindsets in an amazing way.” Others echoed this, stating that an addiction team “legitimized the fact that this is an actual disease that we need to treat - and a failure to treat it is a failure to be a good doctor.”

Providers felt that by addressing addiction directly, “IMPACT elevated the consciousness of providers and nurses … that substance use disorders are brain disorders and not bad behavior.” They described that this legitimization, combined with seeing firsthand the stabilizing effects of medications for addiction, allowed providers to understand SUD as a chronic disease, and not a moral failing.

Providers felt IMPACT improved patient engagement and humanized care by treating withdrawal, directly communicating about SUD, and modeling compassionate care.

Providers noted that treating withdrawal had a dramatic effect on patient engagement and care. One surgeon explained, “by managing their opioid dependence and other substance abuse issues … it’s easier for the staff to take care of them, it’s safer, and the patients feel better taken care of because the staff will engage with them.” Many noted that conflict-ridden “conversations were able to go to the side, and we were able to talk about other things to build rapport.” Others noted that this shift felt like “more productive time.”

In addition, providers repeatedly emphasized that having clear hospital standards and a process to engage patients “really helps … establish rapport with patients: ‘This is how we work this. These are your boundaries. And this is what will happen if you push those boundaries.’ There it is.” Providers attributed improved patient-provider communication to “frank conversation,” “the right amount of empathy,” and a less judgmental environment. As one attending described, “I don’t know if it gives them a voice or allows us to hear them better … but something’s happening with communication.”

Many participants highlighted that IMPACT modeled compassionate bedside interactions, exposed the role of trauma in many patients’ lives, and helped providers see SUD as a disease spectrum. One attending noted that to “actually appreciate the subtleties – just the severity of the disorder – has been powerful.” One resident said:

“There’s definitely a lot of stigma around patients with use disorders that probably shows itself in subtle ways throughout their hospitalization. I think IMPACT does a good job … keeping the patient in the center and keeping their use disorder contextualized in the greater person … [IMPACT] role models bedside interactions and how to treat people like humans.”

Providers valued post-hospital SUD treatment pathways.

Providers valued previously nonexistent post-hospital SUD treatment pathways, stating “this relationship with [community treatment] … it’s like an answer to prayers,” and “this isn’t just like we’re being nicer.” One attending described:

“Starting them on [methadone or buprenorphine-naloxone] and then making the next step in the outpatient world happen has been huge. That transition is so critical … that’s been probably the biggest impact.”

Providers felt relief after IMPACT implementation.

Providers felt that by addressing SUD treatment gaps and providing addiction expertise, IMPACT helped alleviate the previously widespread feelings of “moral distress.” One resident explained “having [IMPACT] as a lifeline, it just feels so good.” As an infectious disease consultant noted, “it makes people more open to treating people if they don’t feel isolated and out of their depth.” Others noted that IMPACT supported better multidisciplinary collaboration, which “reduced a lot of tension between the teams.” One nurse summarized:

“I think you feel more empowered when you’ve got the right medication, … the knowledge, and you feel like you have the resources. You actually feel like you’re making a difference.”

Respondents acknowledged that even with IMPACT, some patients leave AMA or relapse. However, by understanding addiction as a relapsing and remitting disease, providers reconceptualized “success,” further reducing feelings of emotional burnout and stress: “there will be ups and downs, it’s not gonna be a straight linear success.” One case manager reflected,

“Maybe that’s part of the nature of the illness, you progress, and then you kind of hold your breath and then it slips again … at least with IMPACT at the table I can say we’ve done the best we can for this person.”

Perceived limitations of IMPACT:

Providers noted several key limitations of IMPACT, including that hospital-based interventions do not address poverty and have limited ability to address socioeconomic determinants such as “social support, … housing, or nutrition.” Providers also felt that IMPACT had limited ability to alleviate patients’ feelings of boredom and isolation associated with prolonged hospitalization, and that IMPACT had limited effectiveness for highly ambivalent patients (Table 2).

Finally, while many described increased confidence managing SUD after working with IMPACT, others cautioned against deferring too much to specialists. As one resident doctor said:

“We shouldn’t forget that all providers should know how to handle some form of people with addiction … I just don’t want it to be like, ‘oh, well, no, I don’t need to think about this … because we have an addiction specialist.’”

Participants across disciplines repeatedly suggested formal, ongoing initiatives to educate and train providers to manage SUD independently.

DISCUSSION

This study explores provider perspectives on care for hospitalized adults with SUD. Before IMPACT, providers felt care was chaotic, unsafe, and frustrating. Providers perceived variable care quality, resulting in untreated withdrawal, inconsistent care plans, and poor patient outcomes, leading to widespread “moral distress” and feelings of futility among providers. Yet this experience was not inevitable. Providers described that a hospital-based intervention to treat SUD reframed addiction as a treatable chronic disease, transformed culture, and improved patient care and provider experience.

Our findings are consistent with and build on previous research in several ways. First, widespread anxiety and difficulty managing patients with SUD was not unique to our hospital. In a systematic review, van Boekel and colleagues describe that healthcare providers perceived violence, manipulation, and poor motivation as factors impeding care for patients with SUD.9 Our study demonstrates the resulting feelings of powerlessness and frustration may be alleviated through an intervention that provides SUD care.

Second, our study is consistent with a recent survey-based study by Wakeman and colleagues that found that a hospital-based SUD intervention improved providers’ feelings of preparedness and satisfaction.20 Our study provides a rich qualitative description and elucidates mechanisms by which such interventions may work.

The finding that a hospital-based SUD intervention can shift providers’ views of addiction is important. Earlier studies have shown that providers who perceive addiction as a choice are more likely to have negative attitudes toward people with SUD.11 While our intervention did not provide formal education aimed at changing attitudes, participants reported that seeing firsthand effects of treatment on patient behaviors was a powerful tool that radically shifted providers’ understanding and reduced stigma.

Stigma can occur at both individual and organizational levels. Structural stigma refers to practices, policies, and norms of institutions that exclude needs of a particular group.21 The absence of systems to address SUD sends a message to both patients and providers that addiction is a not a treatable or worthy disease. IMPACT was in and of itself a systems-level intervention; by creating a consultation service, hospital-wide policies, and pathways to care after hospitalization, IMPACT ‘legitimized’ SUD and reduced institutional stigma.

Several studies have shown the feasibility and effectiveness of starting medications for addiction (MAT) in the hospital.13-15 Our study builds on this work by highlighting systems-level elements valued by providers. These elements may be important to support and scale widespread adoption of MAT in hospitals. Specifically, providers felt that IMPACT’s attention to hospital policies, use of addiction medicine specialists, and direct linkages to outpatient SUD treatment proved instrumental in shifting care systems.

Our study has several limitations. As a single-site study, our goal was not generalizability, but transferability. As such, we aimed to obtain rich, in-depth information that can inform implementation of similar efforts. Because our study was conducted after the implementation of IMPACT, providers’ perspectives on care before IMPACT may have been influenced by the intervention. However, this also strengthens our findings by allowing participants the opportunity for insights under a different system. It likely leads to distinct findings compared to what we might have uncovered in a pre-post study. While respondents noted perceived limitations of IMPACT, there were few instances of negative remarks in the data we collected. It is possible that providers with more negative interpretations chose not to participate in interviews; however, we elicited wide viewpoints and encouraged participants to share both strengths and weaknesses. Finally, IMPACT implementation depends on regional as well as local factors such as Medicaid expansion, community treatment resources, and the existence of addiction medicine expertise that will differ across settings.

Despite these limitations, our study has several important implications. For clinical practice, our findings highlight the importance of treating withdrawal to address challenging patient behaviors and the value of integrating MAT into the hospital setting. Our findings also underscore the role of expert consultation for addiction. Importantly, our results emphasize that reframing SUD as a brain disease can have significant implications for clinical care and providers’ well-being. Provider distress is not inevitable and can change with the right support and systems.

At the hospital and health systems level, our findings suggest that hospitals can and should address SUD. This may include forming interprofessional teams with SUD expertise, providing standardized guidelines for addiction care such as patient safety plans and methadone policies, and creating rapid-access pathways to outpatient SUD care. By addressing SUD, hospitals may simultaneously improve care and reduce provider burnout. Providers’ important concerns about shifting SUD treatment to a specialty team and their discomfort managing SUD pre-IMPACT suggest the need to integrate SUD education across all levels of interprofessional education. Furthermore, provider concerns that IMPACT has limited ability to engage ambivalent patients underscores the need for hospital-based approaches that emphasize harm reduction strategies.

As the SUD epidemic worsens, SUD-related hospitalizations are skyrocketing, and people are dying at unprecedented rates.2,3 Many efforts to address SUD have been in primary care or community settings. While important, many people with SUD are unable or unlikely to seek primary care. 22 Hospitals need a workforce and systems that can address both the physical and behavioral health needs of this population. By implementing SUD improvements, hospitals can support staff and reduce burnout, better engage patients, improve care, and reduce stigma from this devastating disease

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

1. Rossen L, Bastian B, Warner M, Khan D, Chong Y. Drug poisoning mortality: United States, 1999-2015. 2017; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-visualization/drug-poisoning-mortality/. Accessed 7-11, 2017.

2. Tedesco D, Asch SM, Curtin C, et al. Opioid abuse and poisoning: trends in inpatient and emergency department discharges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1748-1753. http:// doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0260. PubMed

3. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Barrett ML, Steiner CA, Bailey MK, O’Malley L. Statistical Brief #219: Opioid-Related Inpatient Stays and Emergency Department Visits by State, 2009-2014. 2017; https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb219-Opioid-Hospital-Stays-ED-Visits-by-State.jsp?utm_source=AHRQ&utm_medium=EN-2&utm_term=&utm_content=2&utm_campaign=AHRQ_EN12_20_2016. Accessed July 11, 2017. PubMed

4. Ronan MV, Herzig SJ. Hospitalizations related to opioid abuse/dependence and associated serious infections increased sharply, 2002-12. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(5):832-837. http:// doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1424. PubMed

5. Infectious Diseases Society of America Emerging Infections Network. Report for Query: ‘Injection Drug Use (IDU) and Infectious Disease Practice’. 2017; https://www.int-med.uiowa.edu/Research/EIN/FinalReport_IDUandID.pdf. Accessed July 11, 2017.

6. Rosenthal ES, Karchmer AW, Theisen-Toupal J, Castillo RA, Rowley CF. Suboptimal addiction interventions for patients hospitalized with injection drug use-associated infective endocarditis. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):481-485. http:// doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.09.024. PubMed

7. Velez CM, Nicolaidis C, Korthuis PT, Englander H. “It’s been an Experience, a Life Learning Experience”: A qualitative study of hospitalized patients with substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(3):296-303. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3919-4. PubMed

8. Wakeman SE, Pham-Kanter G, Donelan K. Attitudes, practices, and preparedness to care for patients with substance use disorder: Results from a survey of general internists. Subst Abus. 2016;37(4):635-641. http:// doi.org/10.1080/08897077.2016.1187240. PubMed

9. van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HF. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;131(1-2):23-35. http:// doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 PubMed

10. Merrill JO, Rhodes LA, Deyo RA, Marlatt GA, Bradley KA. Mutual mistrust in the medical care of drug users: the keys to the “narc” cabinet. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(5):327-333. http:// doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10625.x. PubMed

11. Brener L, Von Hippel W, Kippax S, Preacher KJ. The role of physician and nurse attitudes in the health care of injecting drug users. Subst Use Misuse. 2010;45(7-8):1007-1018. http:// doi.org/10.3109/10826081003659543. PubMed

12. Wakeman SE, Metlay JP, Chang Y, Herman GE, Rigotti NA. Inpatient addiction consultation for hospitalized patients increases post-discharge abstinence and reduces addiction severity. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(8):909-916. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4077-z. PubMed

13. Wei J, Defries T, Lozada M, Young N, Huen W, Tulsky J. An inpatient treatment and discharge planning protocol for alcohol dependence: efficacy in reducing 30-day readmissions and emergency department visits. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):365-370. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-2968-9. PubMed

14. Liebschutz JM, Crooks D, Herman D, et al. Buprenorphine treatment for hospitalized, opioid-dependent patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1369-1376. http:// doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.2556. PubMed

15. Shanahan CW, Beers D, Alford DP, Brigandi E, Samet JH. A transitional opioid program to engage hospitalized drug users. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(8):803-808. http:// doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1311-3. PubMed

16. Parmelli E, Flodgren G, Beyer F, Baillie N, Schaafsma ME, Eccles MP. The effectiveness of strategies to change organisational culture to improve healthcare performance: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):33. http:// doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-33. PubMed

17. Englander H, Weimer M, Solotaroff R, et al. Planning and designing the improving addiction care team (IMPACT) for hospitalized adults with substance use disorder. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(5):339-342. http:// doi.org/10.12788/jhm.2736. PubMed