User login

Factors Associated with Differential Readmission Diagnoses Following Acute Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Readmissions following hospitalization for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common and economically burdensome.1 The Affordable Care Act2 outlined the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP),3 which aims to improve the quality of care and reduce the costs for patients with pneumonia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and COPD.3 With the implementation of the HRRP, readmission reduction has become a key priority of health systems.

Multiple approaches to reduce readmissions are published, with variable degrees of success across respiratory and all-cause rehospitalizations.4 Patient self-management programs are heterogenous with inconsistent utilization reductions.5-7 While some transitional care programs demonstrate benefits,8-10 one notable study of an intensive transitional care and self-management program showed increaseNod acute care utilization without improving health-related quality of life.11-13 Another study of COPD comprehensive care management was stopped prematurely for increased mortality in the intervention group.14 Telehealth monitoring may predict exacerbations,15,16 but inconsistent effects on quality of life and utilization are observed.17,18 Pulmonary rehabilitation improves quality of life but not healthcare utilization.19 Dispensing respiratory medications at hospital discharge shows improved prescription fills and fewer readmissions,20 further reinforced by inhaler training prior to discharge.21 Postdischarge oxygen therapy does not improve health-related quality of life or acute care utilization.22 The fact that these approaches have not reliably succeeded raises the need for further study on the drivers of readmissions in COPD. Previous studies found differences in factors associated with the timing of COPD readmissions and return diagnoses.23,24 While HRRP is Medicare-specific, health systems likely use programs targeting their entire population when planning readmission reduction strategies. Previous analyses were primarily single-center studies25 and Medicare24 or private insurance claims.26

In this analysis, we explore how comorbidity burden27-29 may differentially influence readmissions for recurrent COPD exacerbations versus other diagnoses. Our approach uses a national all-payer sample that covers a diverse geographic area across the United States, providing robust estimates of factors influencing readmission and valuable insights for planning and implementing effective readmission reduction programs. By including data from a period that encompasses the implementation of HRRP, we also provide new information on the factors in the HRRP postimplementation that are not yet available in published literature.

METHODS

Data Source

The Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) is a nationally representative, all-payer, 100% sample of community acute care hospital discharges from multiple states.30 We pooled COPD discharge records spanning 2010-2016, excluding those where the patients were not residents of the state in which they were hospitalized to minimize loss to follow-up.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Selection criteria mirrored the methodology used by the HRRP,31,32 defining an index discharge as a patient ≥40 years of age with a qualifying COPD diagnosis (Appendix Tables 1-2), discharged alive, with at least 30 days elapsed since previous hospitalization. We excluded discharges against medical advice or those from a hospital with fewer than 25 COPD discharges in that calendar year as per HRRP,31,32 as well as those involving lung transplants. In this pooled cross-sectional analysis, record identifiers were not reliably unique across years. We restricted to observations originating February-November because January stays may not have had the requisite HRRP 30-day washout period from last admission and December stays could not be tracked into the subsequent January.

Outcomes

We defined a readmission as subsequent hospitalization for any cause within 30 days of the index discharge, with exemptions defined by the HRRP (Appendix Figure 1).31,32 We segmented the readmission outcome into two parts: those readmitted with diagnoses that met the COPD HRRP criteria versus for any other diagnoses. We also tabulated diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) coded for the readmission observation to capture attributable cause for rehospitalization.

Our main independent variable was the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score,33 constructed using adaptations of published software,34,35 having previously validated its use for modeling COPD readmissions.36 We involved covariates provided with the database, including sociodemographic variables (eg, age, sex, community characteristics, payer, and median income at patient’s ZIP code) and hospital characteristics (eg, size, ownership, teaching status). We constructed additional covariates to account for in-hospital events by aggregating ICD diagnosis and procedure codes (eg, mechanical ventilation), hospital discharge volume, and proportion of annual within-hospital Medicaid patient days as a surrogate marker for safety-net hospitals. A detailed explanation of database construction and selection criteria is found in the Supplemental Methods Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

We tabulated patient-level descriptive statistics across the three outcomes of interest (ie, not readmitted, readmitted for a stay that would have qualified as COPD-related by HRRP criteria and readmitted for any other diagnosis). Continuous variables were compared using Welch’s t-tests (ie, unequal variance) and categorical variables using Chi-squared tests. At the hospital level, we tabulated the proportions of hospitals within categories in key variables of interest and a sub-population readmission rate for that particular characteristic, compared using Chi-squared tests.

We fit a multilevel multinomial logistic regression with random intercepts at the hospital cluster level, with the tripartite readmission outcome described above with “not readmitted” as the reference group. We included fixed effects for year, Elixhauser score, and patient- and hospital-level covariates as described above. Time to readmission for each group was plotted to assess the time distribution for each outcome. In-hospital mortality during each readmission event was tabulated.

Sensitivity Analyses and Missing Data

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether a lower age cutoff (≥18 years) affects modeling. We also tested the stability of our estimates across each individual year of the pooled analysis. To test the effect of time to differential readmission, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model within the readmitted patient subgroup with Huber-White standard errors clustered at the hospital level to estimate the differential hazard of readmission for COPD versus non-COPD diagnoses across the same variables of interest as a sensitivity analysis. We also tested using a liberal classification of readmission diagnoses by sorting into “respiratory” versus “nonrespiratory” returns, with DRGs 163 through 208 for “respiratory” versus all others, respectively. We tested the agreement between the HRRP ICD-based classification and DRG classification using Cohen’s kappa.

We designated a threshold of 10% missing data to necessitate imputation techniques, determined a priori for our main variables, none of which met this level. Complete case analyses were used for all models. Analyses were performed in Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with weighted estimates reported using patient-level survey weights for national representativeness.37 The study protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board at the University of California, Los Angeles, and deemed exempt from oversight due to the publicly available, deidentified nature of the data (IRB# 18-001208).

RESULTS

Out of 104,897,595 hospitalizations in the NRD, a final sample of 1,622,983 COPD discharges was identified for our analysis (sample weighted effective population 3,743,164). The overall readmission rate was 17.25%, with 7.69% of patients readmitted for COPD and 9.56% readmitted for other diagnoses. Those with COPD readmissions were significantly younger with a lower proportion of Medicare and a higher proportion of Medicaid as the primary payer compared with those readmitted for all other causes (Table 1). Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients were more frequently discharged home without services and had shorter lengths of stay. Noninvasive ventilation was more common among COPD readmissions while mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy placement were less frequent compared with non-COPD readmissions. Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients had significantly lower mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores (17.8 vs 22.8), rates of congestive heart failure (28.3% vs 38.6%), and renal failure (11.8% vs 21.5%; Appendix Table 3).

Readmission rates were significantly higher for non-COPD causes than for COPD causes across all hospital types by ownership, teaching status, or size (Table 2). Parallel patterns were observed for non-COPD and COPD readmissions across hospital types, with two key exceptions. Across categories of hospital ownership, for-profit hospitals had the highest rates for non-COPD readmissions, with no differences in hospital control for COPD rehospitalizations. While rates did not vary for non-COPD readmissions by within-hospital Medicaid prevalence, COPD readmission rates significantly increased as Medicaid-paid patient-days increased within hospitals.

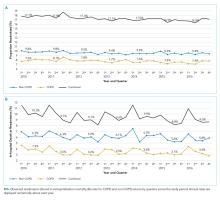

The median time to non-COPD readmission was 13 days, whereas COPD readmission was 14 days. More COPD readmissions occurred in the first 2.4 days after discharge, after which the proportion of non-COPD cases readmitted consistently increased. Observed readmission rates for COPD and other diagnoses trended down over the study period (Figure 1A), as did mortality rates during readmission stays (Figure 1B). Sepsis, heart failure, and respiratory infections were seven of the top 10 ranked DRGs for the non-COPD rehospitalizations (Appendix Table 4). In trend analyses (Appendix Tables 5-8), sepsis and DRGs with major comorbidities increased in proportion each year across the study period, possibly reflecting changes in coding practices.38

In our adjusted multinomial logistic regression model (Table 3), where the outcomes were not readmitted (reference category) versus readmitted for non-COPD diagnosis or for qualifying COPD diagnosis, the effect size of comorbidity, operationalized by change in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, was larger for non-COPD than non-COPD readmissions (odds ratio [OR] 1.19 vs 1.04 per one-half standard deviation of Elixhauser Index, an approximately 7.5 unit change in score). Increases in age were associated with higher non-COPD readmissions (OR 1.06 per 10 years) while actually protective against COPD readmissions (OR 0.89 per 10 years). Compared with Medicare patients, Medicaid patients had higher odds of COPD readmission (OR 1.10 vs 1.03) while the converse was observed in the privately insured (OR 0.65 vs 0.76). Transfers to postacute care facilities, referenced against discharges home, had a larger association with readmissions for non-COPD causes (OR 1.35 vs 1.00), whereas home-health had nearly equal adjusted readmission odds for each outcome (1.31 vs 1.30). Length of stay was associated with 1% greater odds per day for readmission for non-COPD causes than COPD returns. Regarding in-hospital events, odds of COPD readmission were higher for noninvasive ventilation (OR 1.37 vs 0.89) and mechanical ventilation (OR 0.87 vs 0.79, Appendix Table 9), which should be interpreted in the context that analyses were restricted to those discharged alive from their index admission, possibly biasing the true effect estimates due to competing risk of index in-hospital mortality.

In sensitivity analyses, we found no significant differences between our Cox proportional hazards model (Appendix Table 10) and our multinomial model. When we liberalized readmission outcome definitions to respiratory versus nonrespiratory DRGs, we observed 86% agreement between the HRRP and DRG classification systems (κ = 0.73, P < .001). Among the discordant observations, 13% of non-COPD readmissions under HRRP criteria were reclassified as respiratory by DRG and 1% of COPD readmissions under HRRP reclassified as nonrespiratory. When our multinomial model (Appendix Table 11) was re-fit using the DRG-based outcome, only slight changes in effect size occurred. For the Elixhauser Index, the OR for COPD by HRRP was slightly lower than that for respiratory DRGs (1.04 vs 1.05), parallel with the difference between non-COPD by HRRP and nonrespiratory DRG classification (1.19 vs 1.21, respectively). This result underscores the greater influence of comorbidity on non-COPD than COPD readmissions. Only one sign change was observed in those who underwent tracheostomy (OR 0.91 for “nonrespiratory” DRG vs 1.07 for “non-COPD” by HRRP), likely reflecting the shift of some non-COPD diagnoses into the respiratory categorization based on tracheostomy having its own DRG. We also evaluated the multinomial model without the Elixhauser Index (only covariates) and found minor adjustments to the effect sizes of the covariates, particularly for discharge disposition. However, no sign changes were observed for any of the odds ratios (Appendix Table 12). Readmission odds by the Elixhauser score for each condition were stable across years (Appendix Figure 2 & Appendix Table 13). Finally, including 18-39-year-old patients in the cohort did not substantially change our estimates (Appendix Table 14).

DISCUSSION

In this assessment of readmission odds following hospitalizations for COPD in a nationally representative all-payer sample, we demonstrate that 55% of rehospitalizations following COPD exacerbations are attributable to non-COPD diagnoses and describe the important role of comorbidity on influencing diagnoses at rehospitalization. These findings are consistent with a prior study of Medicare patients by Shah et al.24 and expand upon the results of Jacobs et al. using a pre-HRRP sample of the NRD.23 Our study offers an expanded analysis by including data spanning HRRP implementation, which went into effect for COPD in October 2014.3 Effect estimates were stable across all seven years of our study in sensitivity analyses, demonstrating the robustness of our findings. Our analysis also adds to the existing body of literature by assessing which factors are associated with readmissions related to ongoing COPD versus other diagnoses.

In our study, an increase in aggregated comorbidity by the Elixhauser Index was associated with a significantly higher readmission odds, with over four times the effect size for non-COPD than COPD returns. Comorbidity also moderated the effect of other factors, such as income and discharge disposition. While overall readmission rates declined across the course of the study period, the effect of comorbidity on readmission odds for both groups remained significant in annualized models. We also observed higher rates of nearly every individual Elixhauser component comorbidity in those readmitted for non-COPD causes compared with those readmitted for COPD causes. Taken together, these results underscore the need to account for comorbidities at the individual and composite levels when identifying those at highest risk for readmissions and necessitate a multidisciplinary approach to reduce risk for the multimorbid patient.

In a 2018 report, the American Thoracic Society highlighted the focus of programs on adherence to guidelines and reducing variability in COPD care as a potential pitfall in efforts to reduce COPD readmissions.39 We demonstrate that a majority of patients who are readmitted return for diagnoses other than COPD. This finding further highlights that readmission reduction programs need not only focus on COPD control but on the overall management of the patient’s complex medical comorbidities. HRRP penalties are assessed for all-cause readmissions,31,32 and attention to the entire range of diagnoses leading to return to hospital is important to reduce readmission rates and expenditures. Use of strategies such as multispecialty clinics or integrated practice units may be useful in mitigating risk in multimorbid COPD patients.

Other significant factors that deserve further investigation include the use of postacute care services, including home health and skilled nursing facilities. Both factors were associated with higher likelihood of returning for non-COPD than for COPD-related diagnoses. This finding may be collinear to some degree with comorbidity because complex patients are probably less likely to be discharged home directly. Interestingly, those discharged to a postacute care facility had substantially high odds of readmission for a non-COPD cause. Transitional care programs, including short stays in a nursing home, are often employed to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes after discharge in sicker patients,40 which may be insufficient based on these data.

We applied the HRRP criteria for coding a COPD-related admission to the readmission diagnoses, which is more stringent than using only a principal diagnosis or DRGs, to maintain the same standard for defining the index and readmission event. In the sensitivity analyses, we did not find significant differences in our estimates of comorbidity’s effect on outcomes using a more liberal DRG classification system.

We also used DRGs to classify the readmission causes in order to use the same grouping logic that a payer would use when determining the cause. When evaluating which DRG patients returned for following a COPD exacerbation, pneumonia or other respiratory infections make up 13.8%, which may represent the evolution of respiratory infections that provoked the original exacerbation. Heart failure comprised 9.1% of the non-COPD causes, with about one-third of our COPD cohort having known comorbid heart failure at the time of index admission, illustrating significant overlap between these two conditions. Heart failure and pneumonia are conditions of interest in the HRRP and would potentially garner their own penalties had sufficient time elapsed since a prior hospitalization. Among other causes in the top 20 return DRGs were esophagitis, gastritis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and psychoses, which may be potentially associated with the use of corticosteroids to treat a COPD exacerbation, as described in other population studies.41,42 Lack of medication regimen data in our analysis precludes further attribution of these causes, but the potential associations are interesting and warrant additional study.

The structure of our data as pooled annual cross sections rather than a true longitudinal cohort limited us to use only 10 months (February to November) of index hospitalizations in order to stay aligned with HRRP policy inclusion criteria. As such, we may have missed some important observations during peak respiratory virus season. As in any administrative data analysis, we are limited to codes in the discharge records, which may not reflect the entire nature of a hospitalization. Administrative data are particularly problematic in identifying true COPD exacerbations, particularly with multiple comorbid cardiopulmonary conditions.43,44 Validating coding algorithms for identifying COPD was beyond the scope of our evaluation, which purposefully used HRRP methodology. Further study thereof would be a useful endeavor, especially with transition to ICD-10, considering that previously published evaluation was limited to ICD-9.44 Despite these limitations, we were left with a robust and representative national cohort, which is an acceptable tradeoff.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the importance of understanding comorbidity as a major determinant of readmissions following COPD exacerbations, particularly in distinguishing which patients will return for COPD versus non-COPD-related diagnoses. At the health system level, readmission programs should be designed with the multimorbid patient in mind. Engagement of care teams, facilitating communication, and shared decision making are strategies to mitigate readmission risk in addition to COPD-focused disease management.39 These data highlight the need to use risk prediction tools in assigning resources to reduce readmissions,45 as well as the need to move readmission reduction programs beyond COPD management alone. Developing such systems to prospectively identify which patients are at risk of returning for both COPD and non-COPD reasons may further elucidate readmission mitigation strategies and should be a subject of future prospective study.

Acknowledgments

Data were made available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization Project. A full list of partner organizations providing data for the Nationwide Readmission Database can be found at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/hcupdatapartners.jsp.

Prior Presentation

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2018 American Thoracic Society International Conference (May 2018, San Diego, CA). This manuscript is derived from the doctoral dissertation for the degree of PhD in Health Policy and Management of the corresponding author, conferred in June 2019.

Disclaimer

This article does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the USPSTF.

1. Press VG, Konetzka RT, White SR. Insights about the economic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions post implementation of the hospital readmission reduction program. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(2):138-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000454.

2. Patient protection and affordable care act, 124. Stat. 1886;10939:119 U.S.C, §3025(q). 2010).

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. Updated 30 November 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Published. Accessed February 7, 2018; 2017.

4. Shah T, Press VG, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD readmissions: addressing COPD in the era of Value-Based Health Care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916-926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.002.

5. Gadoury MA, Schwartzman K, Rouleau M, et al. Self-management reduces both short- and long-term hospitalisation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):853-857. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00093204.

6. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3(3):CD002990. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub3.

7. Lenferink A, van der Palen J, van der Valk PDLPM, et al. Exacerbation action plans for patients with COPD and comorbidities: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(5). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02134-2018.

8. Jackson CT, Trygstad TK, DeWalt DA, DuBard CA. Transitional care cut hospital readmissions for North Carolina Medicaid patients with complex chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1407-1415. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0047.

9. Verhaegh KJ, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Eslami S et al. Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1531-1539. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0160.

10. Ridwan ES, Hadi H, Wu YL, Tsai PS. Effects of transitional care on hospital readmission and mortality rate in subjects With COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2019;64(9):1146-1156. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06959.

11. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a program combining transitional care and long-term self-management support on outcomes of hospitalized patients With chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2335-2343. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.17933.

12. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a program combining transitional care and long-term self-management support on outcomes of hospitalized patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2335-2343. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.17933.

13. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a hospital-initiated program combining transitional care and long-term self-management support on outcomes of patients hospitalized with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;322(14):1371-1380. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.11982.

14. Fan VS, Gaziano JM, Lew R, et al. A comprehensive care management program to prevent chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospitalizations: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(10):673-683. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-156-10-201205150-00003.

15. Jensen MH, Cichosz SL, Dinesen B, Hejlesen OK. Moving prediction of exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for patients in telecare. J Telemed Telecare. 2012;18(2):99-103. https://doi.org/10.1258/jtt.2011.110607.

16. Pedone C, Chiurco D, Scarlata S, Incalzi RA. Efficacy of multiparametric telemonitoring on respiratory outcomes in elderly people with COPD: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:82. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-82.

17. Pinnock H, Hanley J, McCloughan L, et al. Effectiveness of telemonitoring integrated into existing clinical services on hospital admission for exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: researcher blind, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347:f6070. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f6070.

18. McLean S, Nurmatov U, Liu JL et al. Telehealthcare for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;7(7):CD007718. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007718.pub2.

19. Ko FW, Dai DL, Ngai J, et al. Effect of early pulmonary rehabilitation on health care utilization and health status in patients hospitalized with acute exacerbations of COPD. Respirology. 2011;16(4):617-624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01921.x.

20. Blee J, Roux RK, Gautreaux S, Sherer JT, Garey KW. Dispensing inhalers to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on hospital discharge: effects on prescription filling and readmission. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2015;72(14):1204-1208. https://doi.org/10.2146/ajhp140621.

21. Press VG, Arora VM, Trela KC, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to teach metered-dose and Diskus inhaler techniques. A randomized trial. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2016;13(6):816-824. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-603OC.

22. Eaton T, Fergusson W, Kolbe J, Lewis CA, West T. Short-burst oxygen therapy for COPD patients: a 6-month randomised, controlled study. Eur Respir J. 2006;27(4):697-704. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.06.00098805.

23. Jacobs DM, Noyes K, Zhao J, et al. Early hospital readmissions after an acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2018;15(7):837-845. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201712-913OC.

24. Shah T, Churpek MM, Coca Perraillon M, Konetzka RT. Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansion. Chest. 2015;147(5):1219-1226. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2181.

25. Glaser JB, El-Haddad H. Exploring novel Medicare readmission risk variables in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at high risk of readmission within 30 days of hospital discharge. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2015;12(9):1288-1293. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201504-228OC.

26. Sharif R, Parekh TM, Pierson KS, Kuo YF, Sharma G. Predictors of early readmission among patients 40 to 64 years of age hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2014;11(5):685-694. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-358OC.

27. Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the prevention, diagnosis, and management of COPD. https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-v1.7-FINAL-14Nov2018-WMS.pdf. Published; 2019.

28. Spece LJ, Epler EM, Donovan LM, et al. Role of comorbidities in treatment and outcomes after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2018;15(9):1033-1038. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-255OC.

29. Westney G, Foreman MG, Xu J et al. Impact of comorbidities Among Medicaid enrollees With chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, United States, 2009. Prev Chronic Dis. 2017;14:E31. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd14.160333.

30. HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nrdoverview.jsp; 2010-2016. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Accessed September 1, 2018.

31. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2016 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2016. Available from: https://www.qualitynet.org/files/5d0d3ac7764be766b0104a88?filename=2016_Rdmsn_Msr_Resources.zip. Accessed August 29, 2018.

32. Yale New Haven Health Services Corporation/Center for Outcomes Research & Evaluation. 2017 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures. Baltimore, MD: Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services; 2016. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Downloads/AMI-HF-PN-COPD-and-Stroke-Readmission-Updates.zip. Accessed November 7, 2018.

33. Moore BJ, White S, Washington R, Coenen N, Elixhauser A. Identifying increased risk of readmission and in-hospital mortality using hospital administrative data: the AHRQ Elixhauser comorbidity index. Med Care. 2017;55(7):698-705. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000735.

34. Stagg V. Elixhauser. Stata Module to Calculate Elixhauser Index of Comorbidity [computer program]. Boston: College Department of Economics: Statistical Software Components; 2015.

35. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. HCUP Elixhauser comorbidity software. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp. Accessed March 1, 2019.

36. Buhr RG, Jackson NJ, Kominski GF, et al. Comorbidity and thirty-day hospital readmission odds in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a comparison of the Charlson and Elixhauser comorbidity indices. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):701. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4549-4.

37. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2010-2016.jsp. Published. Updated August 2018. Accessed October 15, 2018.

38. Steinwald B, Dummit LA. Hospital case-mix change: sicker patients or DRG creep? Health Aff (Millwood). 1989;8(2):35-47. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.8.2.35.

39. Press VG, Au DH, Bourbeau J, et al. Reducing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease hospital readmissions. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. Ann Am Thorac Soc. An Official American Thoracic Society Workshop Report. 2019;16(2):161-170. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201811-755WS.

40. McHugh JP, Foster A, Mor V, et al. Reducing hospital readmissions Through preferred networks of skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1591-1598. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0211.

41. Huang KW, Kuan YC, Chi NF et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease is associated with increased recurrent peptic ulcer bleeding risk. Eur J Intern Med. 2017;37:75-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2016.09.020.

42. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Brown ES, et al. Adverse consequences of glucocorticoid medication: psychological, cognitive, and behavioral effects. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(10):1045-1051. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091264.

43. Stein BD, Bautista A, Schumock GT, et al. The validity of International Classification of Diseases, ninth Revision, Clinical Modification diagnosis codes for identifying patients hospitalized for COPD exacerbations. Chest. 2012;141(1):87-93. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.11-0024.

44. Prieto-Centurion V, Rolle AJ, Au DH et al.Multicenter study comparing case definitions used to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(9):989-995. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201406-1166OC.

45. Press VG. Is it time to move on from identifying risk factors for 30-day chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmission? A call for risk prediction tools. Ann Am Thor Soc. 2018;15(7):801-803. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201804-246ED.

Readmissions following hospitalization for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common and economically burdensome.1 The Affordable Care Act2 outlined the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP),3 which aims to improve the quality of care and reduce the costs for patients with pneumonia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and COPD.3 With the implementation of the HRRP, readmission reduction has become a key priority of health systems.

Multiple approaches to reduce readmissions are published, with variable degrees of success across respiratory and all-cause rehospitalizations.4 Patient self-management programs are heterogenous with inconsistent utilization reductions.5-7 While some transitional care programs demonstrate benefits,8-10 one notable study of an intensive transitional care and self-management program showed increaseNod acute care utilization without improving health-related quality of life.11-13 Another study of COPD comprehensive care management was stopped prematurely for increased mortality in the intervention group.14 Telehealth monitoring may predict exacerbations,15,16 but inconsistent effects on quality of life and utilization are observed.17,18 Pulmonary rehabilitation improves quality of life but not healthcare utilization.19 Dispensing respiratory medications at hospital discharge shows improved prescription fills and fewer readmissions,20 further reinforced by inhaler training prior to discharge.21 Postdischarge oxygen therapy does not improve health-related quality of life or acute care utilization.22 The fact that these approaches have not reliably succeeded raises the need for further study on the drivers of readmissions in COPD. Previous studies found differences in factors associated with the timing of COPD readmissions and return diagnoses.23,24 While HRRP is Medicare-specific, health systems likely use programs targeting their entire population when planning readmission reduction strategies. Previous analyses were primarily single-center studies25 and Medicare24 or private insurance claims.26

In this analysis, we explore how comorbidity burden27-29 may differentially influence readmissions for recurrent COPD exacerbations versus other diagnoses. Our approach uses a national all-payer sample that covers a diverse geographic area across the United States, providing robust estimates of factors influencing readmission and valuable insights for planning and implementing effective readmission reduction programs. By including data from a period that encompasses the implementation of HRRP, we also provide new information on the factors in the HRRP postimplementation that are not yet available in published literature.

METHODS

Data Source

The Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) is a nationally representative, all-payer, 100% sample of community acute care hospital discharges from multiple states.30 We pooled COPD discharge records spanning 2010-2016, excluding those where the patients were not residents of the state in which they were hospitalized to minimize loss to follow-up.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Selection criteria mirrored the methodology used by the HRRP,31,32 defining an index discharge as a patient ≥40 years of age with a qualifying COPD diagnosis (Appendix Tables 1-2), discharged alive, with at least 30 days elapsed since previous hospitalization. We excluded discharges against medical advice or those from a hospital with fewer than 25 COPD discharges in that calendar year as per HRRP,31,32 as well as those involving lung transplants. In this pooled cross-sectional analysis, record identifiers were not reliably unique across years. We restricted to observations originating February-November because January stays may not have had the requisite HRRP 30-day washout period from last admission and December stays could not be tracked into the subsequent January.

Outcomes

We defined a readmission as subsequent hospitalization for any cause within 30 days of the index discharge, with exemptions defined by the HRRP (Appendix Figure 1).31,32 We segmented the readmission outcome into two parts: those readmitted with diagnoses that met the COPD HRRP criteria versus for any other diagnoses. We also tabulated diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) coded for the readmission observation to capture attributable cause for rehospitalization.

Our main independent variable was the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score,33 constructed using adaptations of published software,34,35 having previously validated its use for modeling COPD readmissions.36 We involved covariates provided with the database, including sociodemographic variables (eg, age, sex, community characteristics, payer, and median income at patient’s ZIP code) and hospital characteristics (eg, size, ownership, teaching status). We constructed additional covariates to account for in-hospital events by aggregating ICD diagnosis and procedure codes (eg, mechanical ventilation), hospital discharge volume, and proportion of annual within-hospital Medicaid patient days as a surrogate marker for safety-net hospitals. A detailed explanation of database construction and selection criteria is found in the Supplemental Methods Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

We tabulated patient-level descriptive statistics across the three outcomes of interest (ie, not readmitted, readmitted for a stay that would have qualified as COPD-related by HRRP criteria and readmitted for any other diagnosis). Continuous variables were compared using Welch’s t-tests (ie, unequal variance) and categorical variables using Chi-squared tests. At the hospital level, we tabulated the proportions of hospitals within categories in key variables of interest and a sub-population readmission rate for that particular characteristic, compared using Chi-squared tests.

We fit a multilevel multinomial logistic regression with random intercepts at the hospital cluster level, with the tripartite readmission outcome described above with “not readmitted” as the reference group. We included fixed effects for year, Elixhauser score, and patient- and hospital-level covariates as described above. Time to readmission for each group was plotted to assess the time distribution for each outcome. In-hospital mortality during each readmission event was tabulated.

Sensitivity Analyses and Missing Data

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether a lower age cutoff (≥18 years) affects modeling. We also tested the stability of our estimates across each individual year of the pooled analysis. To test the effect of time to differential readmission, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model within the readmitted patient subgroup with Huber-White standard errors clustered at the hospital level to estimate the differential hazard of readmission for COPD versus non-COPD diagnoses across the same variables of interest as a sensitivity analysis. We also tested using a liberal classification of readmission diagnoses by sorting into “respiratory” versus “nonrespiratory” returns, with DRGs 163 through 208 for “respiratory” versus all others, respectively. We tested the agreement between the HRRP ICD-based classification and DRG classification using Cohen’s kappa.

We designated a threshold of 10% missing data to necessitate imputation techniques, determined a priori for our main variables, none of which met this level. Complete case analyses were used for all models. Analyses were performed in Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with weighted estimates reported using patient-level survey weights for national representativeness.37 The study protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board at the University of California, Los Angeles, and deemed exempt from oversight due to the publicly available, deidentified nature of the data (IRB# 18-001208).

RESULTS

Out of 104,897,595 hospitalizations in the NRD, a final sample of 1,622,983 COPD discharges was identified for our analysis (sample weighted effective population 3,743,164). The overall readmission rate was 17.25%, with 7.69% of patients readmitted for COPD and 9.56% readmitted for other diagnoses. Those with COPD readmissions were significantly younger with a lower proportion of Medicare and a higher proportion of Medicaid as the primary payer compared with those readmitted for all other causes (Table 1). Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients were more frequently discharged home without services and had shorter lengths of stay. Noninvasive ventilation was more common among COPD readmissions while mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy placement were less frequent compared with non-COPD readmissions. Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients had significantly lower mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores (17.8 vs 22.8), rates of congestive heart failure (28.3% vs 38.6%), and renal failure (11.8% vs 21.5%; Appendix Table 3).

Readmission rates were significantly higher for non-COPD causes than for COPD causes across all hospital types by ownership, teaching status, or size (Table 2). Parallel patterns were observed for non-COPD and COPD readmissions across hospital types, with two key exceptions. Across categories of hospital ownership, for-profit hospitals had the highest rates for non-COPD readmissions, with no differences in hospital control for COPD rehospitalizations. While rates did not vary for non-COPD readmissions by within-hospital Medicaid prevalence, COPD readmission rates significantly increased as Medicaid-paid patient-days increased within hospitals.

The median time to non-COPD readmission was 13 days, whereas COPD readmission was 14 days. More COPD readmissions occurred in the first 2.4 days after discharge, after which the proportion of non-COPD cases readmitted consistently increased. Observed readmission rates for COPD and other diagnoses trended down over the study period (Figure 1A), as did mortality rates during readmission stays (Figure 1B). Sepsis, heart failure, and respiratory infections were seven of the top 10 ranked DRGs for the non-COPD rehospitalizations (Appendix Table 4). In trend analyses (Appendix Tables 5-8), sepsis and DRGs with major comorbidities increased in proportion each year across the study period, possibly reflecting changes in coding practices.38

In our adjusted multinomial logistic regression model (Table 3), where the outcomes were not readmitted (reference category) versus readmitted for non-COPD diagnosis or for qualifying COPD diagnosis, the effect size of comorbidity, operationalized by change in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, was larger for non-COPD than non-COPD readmissions (odds ratio [OR] 1.19 vs 1.04 per one-half standard deviation of Elixhauser Index, an approximately 7.5 unit change in score). Increases in age were associated with higher non-COPD readmissions (OR 1.06 per 10 years) while actually protective against COPD readmissions (OR 0.89 per 10 years). Compared with Medicare patients, Medicaid patients had higher odds of COPD readmission (OR 1.10 vs 1.03) while the converse was observed in the privately insured (OR 0.65 vs 0.76). Transfers to postacute care facilities, referenced against discharges home, had a larger association with readmissions for non-COPD causes (OR 1.35 vs 1.00), whereas home-health had nearly equal adjusted readmission odds for each outcome (1.31 vs 1.30). Length of stay was associated with 1% greater odds per day for readmission for non-COPD causes than COPD returns. Regarding in-hospital events, odds of COPD readmission were higher for noninvasive ventilation (OR 1.37 vs 0.89) and mechanical ventilation (OR 0.87 vs 0.79, Appendix Table 9), which should be interpreted in the context that analyses were restricted to those discharged alive from their index admission, possibly biasing the true effect estimates due to competing risk of index in-hospital mortality.

In sensitivity analyses, we found no significant differences between our Cox proportional hazards model (Appendix Table 10) and our multinomial model. When we liberalized readmission outcome definitions to respiratory versus nonrespiratory DRGs, we observed 86% agreement between the HRRP and DRG classification systems (κ = 0.73, P < .001). Among the discordant observations, 13% of non-COPD readmissions under HRRP criteria were reclassified as respiratory by DRG and 1% of COPD readmissions under HRRP reclassified as nonrespiratory. When our multinomial model (Appendix Table 11) was re-fit using the DRG-based outcome, only slight changes in effect size occurred. For the Elixhauser Index, the OR for COPD by HRRP was slightly lower than that for respiratory DRGs (1.04 vs 1.05), parallel with the difference between non-COPD by HRRP and nonrespiratory DRG classification (1.19 vs 1.21, respectively). This result underscores the greater influence of comorbidity on non-COPD than COPD readmissions. Only one sign change was observed in those who underwent tracheostomy (OR 0.91 for “nonrespiratory” DRG vs 1.07 for “non-COPD” by HRRP), likely reflecting the shift of some non-COPD diagnoses into the respiratory categorization based on tracheostomy having its own DRG. We also evaluated the multinomial model without the Elixhauser Index (only covariates) and found minor adjustments to the effect sizes of the covariates, particularly for discharge disposition. However, no sign changes were observed for any of the odds ratios (Appendix Table 12). Readmission odds by the Elixhauser score for each condition were stable across years (Appendix Figure 2 & Appendix Table 13). Finally, including 18-39-year-old patients in the cohort did not substantially change our estimates (Appendix Table 14).

DISCUSSION

In this assessment of readmission odds following hospitalizations for COPD in a nationally representative all-payer sample, we demonstrate that 55% of rehospitalizations following COPD exacerbations are attributable to non-COPD diagnoses and describe the important role of comorbidity on influencing diagnoses at rehospitalization. These findings are consistent with a prior study of Medicare patients by Shah et al.24 and expand upon the results of Jacobs et al. using a pre-HRRP sample of the NRD.23 Our study offers an expanded analysis by including data spanning HRRP implementation, which went into effect for COPD in October 2014.3 Effect estimates were stable across all seven years of our study in sensitivity analyses, demonstrating the robustness of our findings. Our analysis also adds to the existing body of literature by assessing which factors are associated with readmissions related to ongoing COPD versus other diagnoses.

In our study, an increase in aggregated comorbidity by the Elixhauser Index was associated with a significantly higher readmission odds, with over four times the effect size for non-COPD than COPD returns. Comorbidity also moderated the effect of other factors, such as income and discharge disposition. While overall readmission rates declined across the course of the study period, the effect of comorbidity on readmission odds for both groups remained significant in annualized models. We also observed higher rates of nearly every individual Elixhauser component comorbidity in those readmitted for non-COPD causes compared with those readmitted for COPD causes. Taken together, these results underscore the need to account for comorbidities at the individual and composite levels when identifying those at highest risk for readmissions and necessitate a multidisciplinary approach to reduce risk for the multimorbid patient.

In a 2018 report, the American Thoracic Society highlighted the focus of programs on adherence to guidelines and reducing variability in COPD care as a potential pitfall in efforts to reduce COPD readmissions.39 We demonstrate that a majority of patients who are readmitted return for diagnoses other than COPD. This finding further highlights that readmission reduction programs need not only focus on COPD control but on the overall management of the patient’s complex medical comorbidities. HRRP penalties are assessed for all-cause readmissions,31,32 and attention to the entire range of diagnoses leading to return to hospital is important to reduce readmission rates and expenditures. Use of strategies such as multispecialty clinics or integrated practice units may be useful in mitigating risk in multimorbid COPD patients.

Other significant factors that deserve further investigation include the use of postacute care services, including home health and skilled nursing facilities. Both factors were associated with higher likelihood of returning for non-COPD than for COPD-related diagnoses. This finding may be collinear to some degree with comorbidity because complex patients are probably less likely to be discharged home directly. Interestingly, those discharged to a postacute care facility had substantially high odds of readmission for a non-COPD cause. Transitional care programs, including short stays in a nursing home, are often employed to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes after discharge in sicker patients,40 which may be insufficient based on these data.

We applied the HRRP criteria for coding a COPD-related admission to the readmission diagnoses, which is more stringent than using only a principal diagnosis or DRGs, to maintain the same standard for defining the index and readmission event. In the sensitivity analyses, we did not find significant differences in our estimates of comorbidity’s effect on outcomes using a more liberal DRG classification system.

We also used DRGs to classify the readmission causes in order to use the same grouping logic that a payer would use when determining the cause. When evaluating which DRG patients returned for following a COPD exacerbation, pneumonia or other respiratory infections make up 13.8%, which may represent the evolution of respiratory infections that provoked the original exacerbation. Heart failure comprised 9.1% of the non-COPD causes, with about one-third of our COPD cohort having known comorbid heart failure at the time of index admission, illustrating significant overlap between these two conditions. Heart failure and pneumonia are conditions of interest in the HRRP and would potentially garner their own penalties had sufficient time elapsed since a prior hospitalization. Among other causes in the top 20 return DRGs were esophagitis, gastritis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and psychoses, which may be potentially associated with the use of corticosteroids to treat a COPD exacerbation, as described in other population studies.41,42 Lack of medication regimen data in our analysis precludes further attribution of these causes, but the potential associations are interesting and warrant additional study.

The structure of our data as pooled annual cross sections rather than a true longitudinal cohort limited us to use only 10 months (February to November) of index hospitalizations in order to stay aligned with HRRP policy inclusion criteria. As such, we may have missed some important observations during peak respiratory virus season. As in any administrative data analysis, we are limited to codes in the discharge records, which may not reflect the entire nature of a hospitalization. Administrative data are particularly problematic in identifying true COPD exacerbations, particularly with multiple comorbid cardiopulmonary conditions.43,44 Validating coding algorithms for identifying COPD was beyond the scope of our evaluation, which purposefully used HRRP methodology. Further study thereof would be a useful endeavor, especially with transition to ICD-10, considering that previously published evaluation was limited to ICD-9.44 Despite these limitations, we were left with a robust and representative national cohort, which is an acceptable tradeoff.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the importance of understanding comorbidity as a major determinant of readmissions following COPD exacerbations, particularly in distinguishing which patients will return for COPD versus non-COPD-related diagnoses. At the health system level, readmission programs should be designed with the multimorbid patient in mind. Engagement of care teams, facilitating communication, and shared decision making are strategies to mitigate readmission risk in addition to COPD-focused disease management.39 These data highlight the need to use risk prediction tools in assigning resources to reduce readmissions,45 as well as the need to move readmission reduction programs beyond COPD management alone. Developing such systems to prospectively identify which patients are at risk of returning for both COPD and non-COPD reasons may further elucidate readmission mitigation strategies and should be a subject of future prospective study.

Acknowledgments

Data were made available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization Project. A full list of partner organizations providing data for the Nationwide Readmission Database can be found at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/hcupdatapartners.jsp.

Prior Presentation

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2018 American Thoracic Society International Conference (May 2018, San Diego, CA). This manuscript is derived from the doctoral dissertation for the degree of PhD in Health Policy and Management of the corresponding author, conferred in June 2019.

Disclaimer

This article does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the USPSTF.

Readmissions following hospitalization for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) are common and economically burdensome.1 The Affordable Care Act2 outlined the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP),3 which aims to improve the quality of care and reduce the costs for patients with pneumonia, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, and COPD.3 With the implementation of the HRRP, readmission reduction has become a key priority of health systems.

Multiple approaches to reduce readmissions are published, with variable degrees of success across respiratory and all-cause rehospitalizations.4 Patient self-management programs are heterogenous with inconsistent utilization reductions.5-7 While some transitional care programs demonstrate benefits,8-10 one notable study of an intensive transitional care and self-management program showed increaseNod acute care utilization without improving health-related quality of life.11-13 Another study of COPD comprehensive care management was stopped prematurely for increased mortality in the intervention group.14 Telehealth monitoring may predict exacerbations,15,16 but inconsistent effects on quality of life and utilization are observed.17,18 Pulmonary rehabilitation improves quality of life but not healthcare utilization.19 Dispensing respiratory medications at hospital discharge shows improved prescription fills and fewer readmissions,20 further reinforced by inhaler training prior to discharge.21 Postdischarge oxygen therapy does not improve health-related quality of life or acute care utilization.22 The fact that these approaches have not reliably succeeded raises the need for further study on the drivers of readmissions in COPD. Previous studies found differences in factors associated with the timing of COPD readmissions and return diagnoses.23,24 While HRRP is Medicare-specific, health systems likely use programs targeting their entire population when planning readmission reduction strategies. Previous analyses were primarily single-center studies25 and Medicare24 or private insurance claims.26

In this analysis, we explore how comorbidity burden27-29 may differentially influence readmissions for recurrent COPD exacerbations versus other diagnoses. Our approach uses a national all-payer sample that covers a diverse geographic area across the United States, providing robust estimates of factors influencing readmission and valuable insights for planning and implementing effective readmission reduction programs. By including data from a period that encompasses the implementation of HRRP, we also provide new information on the factors in the HRRP postimplementation that are not yet available in published literature.

METHODS

Data Source

The Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) is a nationally representative, all-payer, 100% sample of community acute care hospital discharges from multiple states.30 We pooled COPD discharge records spanning 2010-2016, excluding those where the patients were not residents of the state in which they were hospitalized to minimize loss to follow-up.

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

Selection criteria mirrored the methodology used by the HRRP,31,32 defining an index discharge as a patient ≥40 years of age with a qualifying COPD diagnosis (Appendix Tables 1-2), discharged alive, with at least 30 days elapsed since previous hospitalization. We excluded discharges against medical advice or those from a hospital with fewer than 25 COPD discharges in that calendar year as per HRRP,31,32 as well as those involving lung transplants. In this pooled cross-sectional analysis, record identifiers were not reliably unique across years. We restricted to observations originating February-November because January stays may not have had the requisite HRRP 30-day washout period from last admission and December stays could not be tracked into the subsequent January.

Outcomes

We defined a readmission as subsequent hospitalization for any cause within 30 days of the index discharge, with exemptions defined by the HRRP (Appendix Figure 1).31,32 We segmented the readmission outcome into two parts: those readmitted with diagnoses that met the COPD HRRP criteria versus for any other diagnoses. We also tabulated diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) coded for the readmission observation to capture attributable cause for rehospitalization.

Our main independent variable was the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index score,33 constructed using adaptations of published software,34,35 having previously validated its use for modeling COPD readmissions.36 We involved covariates provided with the database, including sociodemographic variables (eg, age, sex, community characteristics, payer, and median income at patient’s ZIP code) and hospital characteristics (eg, size, ownership, teaching status). We constructed additional covariates to account for in-hospital events by aggregating ICD diagnosis and procedure codes (eg, mechanical ventilation), hospital discharge volume, and proportion of annual within-hospital Medicaid patient days as a surrogate marker for safety-net hospitals. A detailed explanation of database construction and selection criteria is found in the Supplemental Methods Appendix.

Statistical Analysis

We tabulated patient-level descriptive statistics across the three outcomes of interest (ie, not readmitted, readmitted for a stay that would have qualified as COPD-related by HRRP criteria and readmitted for any other diagnosis). Continuous variables were compared using Welch’s t-tests (ie, unequal variance) and categorical variables using Chi-squared tests. At the hospital level, we tabulated the proportions of hospitals within categories in key variables of interest and a sub-population readmission rate for that particular characteristic, compared using Chi-squared tests.

We fit a multilevel multinomial logistic regression with random intercepts at the hospital cluster level, with the tripartite readmission outcome described above with “not readmitted” as the reference group. We included fixed effects for year, Elixhauser score, and patient- and hospital-level covariates as described above. Time to readmission for each group was plotted to assess the time distribution for each outcome. In-hospital mortality during each readmission event was tabulated.

Sensitivity Analyses and Missing Data

We conducted sensitivity analyses to determine whether a lower age cutoff (≥18 years) affects modeling. We also tested the stability of our estimates across each individual year of the pooled analysis. To test the effect of time to differential readmission, we fit a Cox proportional hazards model within the readmitted patient subgroup with Huber-White standard errors clustered at the hospital level to estimate the differential hazard of readmission for COPD versus non-COPD diagnoses across the same variables of interest as a sensitivity analysis. We also tested using a liberal classification of readmission diagnoses by sorting into “respiratory” versus “nonrespiratory” returns, with DRGs 163 through 208 for “respiratory” versus all others, respectively. We tested the agreement between the HRRP ICD-based classification and DRG classification using Cohen’s kappa.

We designated a threshold of 10% missing data to necessitate imputation techniques, determined a priori for our main variables, none of which met this level. Complete case analyses were used for all models. Analyses were performed in Stata version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas) with weighted estimates reported using patient-level survey weights for national representativeness.37 The study protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board at the University of California, Los Angeles, and deemed exempt from oversight due to the publicly available, deidentified nature of the data (IRB# 18-001208).

RESULTS

Out of 104,897,595 hospitalizations in the NRD, a final sample of 1,622,983 COPD discharges was identified for our analysis (sample weighted effective population 3,743,164). The overall readmission rate was 17.25%, with 7.69% of patients readmitted for COPD and 9.56% readmitted for other diagnoses. Those with COPD readmissions were significantly younger with a lower proportion of Medicare and a higher proportion of Medicaid as the primary payer compared with those readmitted for all other causes (Table 1). Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients were more frequently discharged home without services and had shorter lengths of stay. Noninvasive ventilation was more common among COPD readmissions while mechanical ventilation and tracheostomy placement were less frequent compared with non-COPD readmissions. Compared with non-COPD-readmitted patients, COPD-readmitted patients had significantly lower mean Elixhauser Comorbidity Index scores (17.8 vs 22.8), rates of congestive heart failure (28.3% vs 38.6%), and renal failure (11.8% vs 21.5%; Appendix Table 3).

Readmission rates were significantly higher for non-COPD causes than for COPD causes across all hospital types by ownership, teaching status, or size (Table 2). Parallel patterns were observed for non-COPD and COPD readmissions across hospital types, with two key exceptions. Across categories of hospital ownership, for-profit hospitals had the highest rates for non-COPD readmissions, with no differences in hospital control for COPD rehospitalizations. While rates did not vary for non-COPD readmissions by within-hospital Medicaid prevalence, COPD readmission rates significantly increased as Medicaid-paid patient-days increased within hospitals.

The median time to non-COPD readmission was 13 days, whereas COPD readmission was 14 days. More COPD readmissions occurred in the first 2.4 days after discharge, after which the proportion of non-COPD cases readmitted consistently increased. Observed readmission rates for COPD and other diagnoses trended down over the study period (Figure 1A), as did mortality rates during readmission stays (Figure 1B). Sepsis, heart failure, and respiratory infections were seven of the top 10 ranked DRGs for the non-COPD rehospitalizations (Appendix Table 4). In trend analyses (Appendix Tables 5-8), sepsis and DRGs with major comorbidities increased in proportion each year across the study period, possibly reflecting changes in coding practices.38

In our adjusted multinomial logistic regression model (Table 3), where the outcomes were not readmitted (reference category) versus readmitted for non-COPD diagnosis or for qualifying COPD diagnosis, the effect size of comorbidity, operationalized by change in the Elixhauser Comorbidity Index, was larger for non-COPD than non-COPD readmissions (odds ratio [OR] 1.19 vs 1.04 per one-half standard deviation of Elixhauser Index, an approximately 7.5 unit change in score). Increases in age were associated with higher non-COPD readmissions (OR 1.06 per 10 years) while actually protective against COPD readmissions (OR 0.89 per 10 years). Compared with Medicare patients, Medicaid patients had higher odds of COPD readmission (OR 1.10 vs 1.03) while the converse was observed in the privately insured (OR 0.65 vs 0.76). Transfers to postacute care facilities, referenced against discharges home, had a larger association with readmissions for non-COPD causes (OR 1.35 vs 1.00), whereas home-health had nearly equal adjusted readmission odds for each outcome (1.31 vs 1.30). Length of stay was associated with 1% greater odds per day for readmission for non-COPD causes than COPD returns. Regarding in-hospital events, odds of COPD readmission were higher for noninvasive ventilation (OR 1.37 vs 0.89) and mechanical ventilation (OR 0.87 vs 0.79, Appendix Table 9), which should be interpreted in the context that analyses were restricted to those discharged alive from their index admission, possibly biasing the true effect estimates due to competing risk of index in-hospital mortality.

In sensitivity analyses, we found no significant differences between our Cox proportional hazards model (Appendix Table 10) and our multinomial model. When we liberalized readmission outcome definitions to respiratory versus nonrespiratory DRGs, we observed 86% agreement between the HRRP and DRG classification systems (κ = 0.73, P < .001). Among the discordant observations, 13% of non-COPD readmissions under HRRP criteria were reclassified as respiratory by DRG and 1% of COPD readmissions under HRRP reclassified as nonrespiratory. When our multinomial model (Appendix Table 11) was re-fit using the DRG-based outcome, only slight changes in effect size occurred. For the Elixhauser Index, the OR for COPD by HRRP was slightly lower than that for respiratory DRGs (1.04 vs 1.05), parallel with the difference between non-COPD by HRRP and nonrespiratory DRG classification (1.19 vs 1.21, respectively). This result underscores the greater influence of comorbidity on non-COPD than COPD readmissions. Only one sign change was observed in those who underwent tracheostomy (OR 0.91 for “nonrespiratory” DRG vs 1.07 for “non-COPD” by HRRP), likely reflecting the shift of some non-COPD diagnoses into the respiratory categorization based on tracheostomy having its own DRG. We also evaluated the multinomial model without the Elixhauser Index (only covariates) and found minor adjustments to the effect sizes of the covariates, particularly for discharge disposition. However, no sign changes were observed for any of the odds ratios (Appendix Table 12). Readmission odds by the Elixhauser score for each condition were stable across years (Appendix Figure 2 & Appendix Table 13). Finally, including 18-39-year-old patients in the cohort did not substantially change our estimates (Appendix Table 14).

DISCUSSION

In this assessment of readmission odds following hospitalizations for COPD in a nationally representative all-payer sample, we demonstrate that 55% of rehospitalizations following COPD exacerbations are attributable to non-COPD diagnoses and describe the important role of comorbidity on influencing diagnoses at rehospitalization. These findings are consistent with a prior study of Medicare patients by Shah et al.24 and expand upon the results of Jacobs et al. using a pre-HRRP sample of the NRD.23 Our study offers an expanded analysis by including data spanning HRRP implementation, which went into effect for COPD in October 2014.3 Effect estimates were stable across all seven years of our study in sensitivity analyses, demonstrating the robustness of our findings. Our analysis also adds to the existing body of literature by assessing which factors are associated with readmissions related to ongoing COPD versus other diagnoses.

In our study, an increase in aggregated comorbidity by the Elixhauser Index was associated with a significantly higher readmission odds, with over four times the effect size for non-COPD than COPD returns. Comorbidity also moderated the effect of other factors, such as income and discharge disposition. While overall readmission rates declined across the course of the study period, the effect of comorbidity on readmission odds for both groups remained significant in annualized models. We also observed higher rates of nearly every individual Elixhauser component comorbidity in those readmitted for non-COPD causes compared with those readmitted for COPD causes. Taken together, these results underscore the need to account for comorbidities at the individual and composite levels when identifying those at highest risk for readmissions and necessitate a multidisciplinary approach to reduce risk for the multimorbid patient.

In a 2018 report, the American Thoracic Society highlighted the focus of programs on adherence to guidelines and reducing variability in COPD care as a potential pitfall in efforts to reduce COPD readmissions.39 We demonstrate that a majority of patients who are readmitted return for diagnoses other than COPD. This finding further highlights that readmission reduction programs need not only focus on COPD control but on the overall management of the patient’s complex medical comorbidities. HRRP penalties are assessed for all-cause readmissions,31,32 and attention to the entire range of diagnoses leading to return to hospital is important to reduce readmission rates and expenditures. Use of strategies such as multispecialty clinics or integrated practice units may be useful in mitigating risk in multimorbid COPD patients.

Other significant factors that deserve further investigation include the use of postacute care services, including home health and skilled nursing facilities. Both factors were associated with higher likelihood of returning for non-COPD than for COPD-related diagnoses. This finding may be collinear to some degree with comorbidity because complex patients are probably less likely to be discharged home directly. Interestingly, those discharged to a postacute care facility had substantially high odds of readmission for a non-COPD cause. Transitional care programs, including short stays in a nursing home, are often employed to mitigate the risk of adverse outcomes after discharge in sicker patients,40 which may be insufficient based on these data.

We applied the HRRP criteria for coding a COPD-related admission to the readmission diagnoses, which is more stringent than using only a principal diagnosis or DRGs, to maintain the same standard for defining the index and readmission event. In the sensitivity analyses, we did not find significant differences in our estimates of comorbidity’s effect on outcomes using a more liberal DRG classification system.

We also used DRGs to classify the readmission causes in order to use the same grouping logic that a payer would use when determining the cause. When evaluating which DRG patients returned for following a COPD exacerbation, pneumonia or other respiratory infections make up 13.8%, which may represent the evolution of respiratory infections that provoked the original exacerbation. Heart failure comprised 9.1% of the non-COPD causes, with about one-third of our COPD cohort having known comorbid heart failure at the time of index admission, illustrating significant overlap between these two conditions. Heart failure and pneumonia are conditions of interest in the HRRP and would potentially garner their own penalties had sufficient time elapsed since a prior hospitalization. Among other causes in the top 20 return DRGs were esophagitis, gastritis, gastrointestinal bleeding, and psychoses, which may be potentially associated with the use of corticosteroids to treat a COPD exacerbation, as described in other population studies.41,42 Lack of medication regimen data in our analysis precludes further attribution of these causes, but the potential associations are interesting and warrant additional study.

The structure of our data as pooled annual cross sections rather than a true longitudinal cohort limited us to use only 10 months (February to November) of index hospitalizations in order to stay aligned with HRRP policy inclusion criteria. As such, we may have missed some important observations during peak respiratory virus season. As in any administrative data analysis, we are limited to codes in the discharge records, which may not reflect the entire nature of a hospitalization. Administrative data are particularly problematic in identifying true COPD exacerbations, particularly with multiple comorbid cardiopulmonary conditions.43,44 Validating coding algorithms for identifying COPD was beyond the scope of our evaluation, which purposefully used HRRP methodology. Further study thereof would be a useful endeavor, especially with transition to ICD-10, considering that previously published evaluation was limited to ICD-9.44 Despite these limitations, we were left with a robust and representative national cohort, which is an acceptable tradeoff.

CONCLUSION

Our study highlights the importance of understanding comorbidity as a major determinant of readmissions following COPD exacerbations, particularly in distinguishing which patients will return for COPD versus non-COPD-related diagnoses. At the health system level, readmission programs should be designed with the multimorbid patient in mind. Engagement of care teams, facilitating communication, and shared decision making are strategies to mitigate readmission risk in addition to COPD-focused disease management.39 These data highlight the need to use risk prediction tools in assigning resources to reduce readmissions,45 as well as the need to move readmission reduction programs beyond COPD management alone. Developing such systems to prospectively identify which patients are at risk of returning for both COPD and non-COPD reasons may further elucidate readmission mitigation strategies and should be a subject of future prospective study.

Acknowledgments

Data were made available through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s Healthcare Utilization Project. A full list of partner organizations providing data for the Nationwide Readmission Database can be found at https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/hcupdatapartners.jsp.

Prior Presentation

Portions of this work were presented in abstract form at the 2018 American Thoracic Society International Conference (May 2018, San Diego, CA). This manuscript is derived from the doctoral dissertation for the degree of PhD in Health Policy and Management of the corresponding author, conferred in June 2019.

Disclaimer

This article does not necessarily represent the views and policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the USPSTF.

1. Press VG, Konetzka RT, White SR. Insights about the economic impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease readmissions post implementation of the hospital readmission reduction program. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2018;24(2):138-146. https://doi.org/10.1097/MCP.0000000000000454.

2. Patient protection and affordable care act, 124. Stat. 1886;10939:119 U.S.C, §3025(q). 2010).

3. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Readmissions Reduction Program. Updated 30 November 2017. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions-Reduction-Program.html. Published. Accessed February 7, 2018; 2017.

4. Shah T, Press VG, Huisingh-Scheetz M, White SR. COPD readmissions: addressing COPD in the era of Value-Based Health Care. Chest. 2016;150(4):916-926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2016.05.002.

5. Gadoury MA, Schwartzman K, Rouleau M, et al. Self-management reduces both short- and long-term hospitalisation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2005;26(5):853-857. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.05.00093204.

6. Zwerink M, Brusse-Keizer M, van der Valk PD, et al. Self management for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;3(3):CD002990. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002990.pub3.

7. Lenferink A, van der Palen J, van der Valk PDLPM, et al. Exacerbation action plans for patients with COPD and comorbidities: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J. 2019;54(5). https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.02134-2018.

8. Jackson CT, Trygstad TK, DeWalt DA, DuBard CA. Transitional care cut hospital readmissions for North Carolina Medicaid patients with complex chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(8):1407-1415. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0047.

9. Verhaegh KJ, MacNeil-Vroomen JL, Eslami S et al. Transitional care interventions prevent hospital readmissions for adults with chronic illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1531-1539. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0160.

10. Ridwan ES, Hadi H, Wu YL, Tsai PS. Effects of transitional care on hospital readmission and mortality rate in subjects With COPD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Care. 2019;64(9):1146-1156. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.06959.

11. Aboumatar H, Naqibuddin M, Chung S, et al. Effect of a program combining transitional care and long-term self-management support on outcomes of hospitalized patients With chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320(22):2335-2343. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.17933.