User login

A First Look at the VA MISSION Act Veteran Health Administration Medical School Scholarship and Loan Repayment Programs

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

Health Professions Scholarship

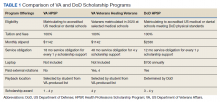

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

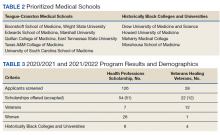

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

Health Professions Scholarship

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

As one of 4 statutory missions, the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) educates and trains health professionals to enhance the quality of and timely access to care provided to veterans within the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). To achieve its mission to

Despite its long-term success affiliating with medical schools, VA has continued to be challenged by physician staff shortages with wide variability in the number and specialty of available health care professionals across facilities.3,4 A 2020 VA Office of Inspector General report on VHA occupational staffing shortages concluded that numerous physician specialties were difficult to recruit due to a lack of qualified applicants, noncompetitive salary, and less desirable geographic locations.3

Federal health professions scholarship programs and loan repayment programs have long been used to address physician shortages.4 Focusing on physician shortages in underserved areas in the US, the Emergency Health Personnel Act of 1970 and its subsequent amendments paved the way for various federal medical school scholarship and loan repayment programs.5 Similarly, physician shortages in the armed forces were mitigated through the Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972 (USHPRA).6,7

In 2018, Congress passed the VA MISSION (Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks) Act, which included sections designed to alleviate physician shortages in the VHA.8 These sections authorized scholarships similar to those offered by the US Department of Defense (DoD) and loan repayment programs. Section 301 created the Health Professions Scholarship Program (HPSP), which offers scholarships for physicians and dentists. Section 302 increased the maximum debt reduction through the Education Debt Reduction Program (EDRP). Section 303 authorizes the Specialty Education Loan Repayment Program (SELRP), which provides for repayment of educational loans for physicians in specialties deemed necessary for VA. Finally, Section 304 created the Veterans Healing Veterans (VHV), a pilot scholarship specifically for veteran medical students.

Program Characteristics

Health Professions Scholarship

The VA HPSP is a program for physicians and dentists that extends from 2020 to 2033. The HPSP funds the costs of tuition, fees, and provides a stipend with a service obligation of 18 months for each year of support. The program is authorized for 10 years and must provide a minimum of 50 scholarships annually for physicians or dentists based on VHA needs. Applications are screened based on criteria that include a commitment to rural or underserved populations, veteran status, grade point average, essays, and letters of recommendation. Although the minimum required number of scholarships annually is 50, VA anticipates providing 1000 scholarships over 10 years with an aim to significantly increase the number physicians at VHA facilities (Table 1).

Implemented in 2020, the VHV was a 1-year pilot program. It offered scholarships to 2 veterans attending medical school at each of the 5 Teague-Cranston and the 4 Historically Black College and University (HBCU) medical schools (Table 2). The intent of the program was to determine the feasibility of increasing the pool of veteran physicians at VHA. Eligible applicants were notified of the scholarship opportunity through the American Medical College Application Service or through the medical school. Applicants must have separated from military service within the preceding 10 years of being admitted to medical school. In exchange for full tuition, fees, a monthly stipend, and rotation travel costs, the recipients accepted a 4-year clinical service obligation at VA facilities after completing their residency training.

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

The SELRP is a loan repayment program available to recently graduated physicians. Applicants must have graduated from an accredited medical or osteopathic school, matched to an accredited residency program and be ≥ 2 years from completion of residency. The specialties qualifying for SELRP are determined through an analysis of succession planning by the VA Office of Workforce Management and Consulting and change based on VA physician workforce needs. The SELRP provides loan repayment in the amount of $40,000 per year for up to 4 years, with a service obligation of 1 year for each $40,000 of support. In April 2021, VA began accepting applications from the eligible specialties of family medicine, internal medicine, gastroenterology, psychiatry, emergency medicine, and geriatrics.

Education Debt Reduction

The EDRP offers debt relief to clinicians in the most difficult to recruit professions, including physicians (generalists and specialists), registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, social workers, and psychologists. The list of difficult to recruit positions is developed annually by VA facilities. Annual reimbursements through the program may be used for tuition and expenses, such as fees, books, supplies, equipment, and other materials. In 2018, through the MISSION Act Section 302, the annual loan repayment was increased from $24,000 to $40,000, and the maximum level of support was increased from $120,000 to $200,000 over 5 years. Recipients receive reimbursement for loan repayment at the end of each year or service period and recipients are not required to remain in VA for 5 years.

Program Results

Health Professions Scholarship

For academic years 2020/2021 and 2021/2022, 126 HPSP applications from both allopathic and osteopathic schools were submitted and 51 scholarships were awarded (Table 3). Assuming an average residency length of 4 years, VHA estimates that these awards will yield 204 service-year equivalents by 2029.

Veterans Healing Veterans

In the VHV program, scholarship recipients came from 5 Teague-Cranston schools; 2 at University of South Carolina, 2 at East Tennessee State University, 2 at Wright State University, 1 at Texas A&M College of Medicine, 1 at Marshall University; and 3 HBCUs; 2 at Howard University, 1 at Morehouse School of Medicine and 1 at Meharry Medical College. The Charles R. Drew University of Medicine and Science did not nominate any students for the scholarship. Assuming all recipients complete postgraduate training, the VHV scholarship program will provide an additional 12 veteran physicians to serve at VA for at least 4 years each (48 service years).

Specialty Education Loan Repayment

Fourteen applicants have been approved, including 5 in psychiatry, 4 in family medicine, 3 in internal medicine, 1 in emergency medicine, and 1 in geriatrics. The mean loan repayment is anticipated to be $110,000 and equating to 38.5 VA service years or a mean of 2.3 years of service obligation per individual for the first cohort. The program has no termination date, and with continued funding, VA anticipates granting 100 loan repayments annually.

Education Debt Reduction

Since 2018, 1,546 VA physicians have received EDRP awards. Due to the increased reimbursement provided through the MISSION Act, average physician award amounts have increased from $96,090 in 2018 to $142,557 in 2019 and $148,302 in 2020.

Conclusions

The VA physician scholarship and loan repayment programs outlined in the MISSION Act build on the success of existing federal scholarship programs by providing opportunities for physician trainees to alleviate educational debt and explore a VA health professions career.

Looking ahead, VA must focus on measuring the success of the MISSION scholarship and loan repayment programs by tracking rates of acceptance and student graduation, residency and fellowship completion, and placement in VA medical facilities—both for the service obligation and future employment. Ultimately, the total impact on VA staffing, especially at rural and underresourced sites, will determine the success of the MISSION programs.

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

1. VA Policy Memorandum #2. Policy in Association of Veterans’ Hospitals with Medical Schools. US Department of Veterans Affairs. January 20, 1946. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf 2. Gilman SC, Chang BK, Zeiss RA, Dougherty MB, Marks WJ, Ludke DA, Cox M. “The academic mission of the Department of Veterans Affairs.” In: Praeger Handbook of Veterans’ Health: History, Challenges, Issues, and Developments. Praeger; 2012:53-82.

3. Office of Inspector General, Veterans Health Administration OIG Determination of VHA Occupational Staffing Shortages FY2020. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Published September 23, 2020. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.va.gov/oig/pubs/VAOIG-20-01249-259.pdf

4. Hussey PS, Ringel J, et al. Resources and capabilities of the Department of Veterans Affairs to provide timely and accessible care to veterans. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(4). Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR1100/RR1165z2/RAND_RR1165z2.pdf

5. Lynch A, Best T, Gutierrez SC, Daily JA. What Should I Do With My Student Loans? A Proposed Strategy for Educational Debt Management. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(1):11-15. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00279.1

6. The Uniformed Services Health Professions Revitalization Act of 1972, PL 92-426. US Government Publishing Office. Published 1972. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/STATUTE-86/pdf/STATUTE-86-Pg713.pdf

7. Armed Forces Health Professions Financial Assistance Programs, 10 USC § 105 (2006).

8. ‘‘VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act of 2018’’. H.R. 5674. 115th Congress; Report No. 115-671, Part 1. May 3, 2018. Accessed February 17, 2022. https://www.congress.gov/115/bills/hr5674/BILLS-115hr5674rh.pdf

A Year 3 Progress Report on Graduate Medical Education Expansion in the Veterans Choice Act

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution

To distribute these newly created GME positions as mandated by Congress, the OAA is using a system with 3 types of request for proposal (RFP) applications. These include planning, infrastructure, and position grants. This phased approach was taken with the understanding that the development of new training sites requires a properly staffed education office and dedicated faculty time. Planning and infrastructure grants provide start-up funds for smaller VAMCs, allowing them to keep facility resources focused on their clinical mission.

Planning grants (of up to $250,000 over 2 years) primarily were designed for VA facilities with no or low numbers of physician residents at the desired teaching location. Priority was given to facilities in rural and/or underserved areas as well as those developing new affiliations. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with peer-selected Designated Education Officers (DEOs) from VA facilities across the nation that were not applying for the grants. Awards were based on the priorities mentioned earlier, with additional credit for programs focused on 2 VHA fundamental services areas—primary care and/or mental health training. Facilities receiving planning grants were mentored by an OAA physician staff member, anticipating a 2- to 3-year time line to request positions and begin GME training.

Infrastructure grants (of up to $520,000 used over 2-3 years) were designed as bridge funds after approval of Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) GME positions. Infrastructure grants are appropriate to sustain a local education office, develop VA faculty, purchase equipment, and make minor modifications to the clinical space in the VAMCs or CBOCs to enhance the learning environment during the period before VA supportive funds from the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) (similar to indirect GME funds from CMS) become available. Applications were managed the same as planning grant submissions.

Position RFPs, unlike planning and infrastructure RFPs, are available to all VAMCs. The primary purpose of the VACAA Position RFP is to fund new positions in primary care and psychiatry. Graduate medical education positions in subspecialty programs also are considered when there is documentation of critical need to improve access to these services. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with selected DEOs from VA facilities around the U.S. Award criteria prioritized primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics), and mental health (psychiatry and psychiatry subspecialties). Priority also was given to positions in areas with a documented shortage of physicians and areas with high concentrations of veterans.

Current Progress

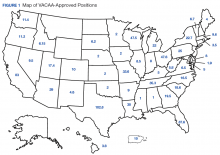

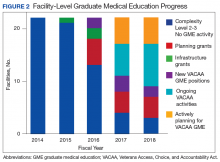

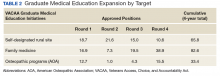

To date the OAA has offered 3 RFP cycles consisting of planning/infrastructure grants, and 4 RFP cycles for salary/benefit support for additional resident full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Resident positions were defined as residency or fellowship FTEs that were part of an ACGME or AOA-accredited training program. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of awarded GME positions.

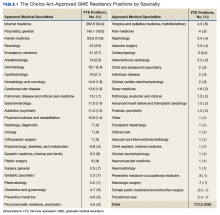

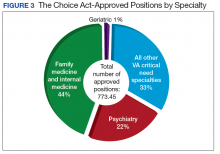

In primary care specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics, a total of 349.4 FTE positions have been approved (Table 1). Due to a low number of applications, only 6.3 of these positions were awarded in geriatrics. In mental health, 167.6 FTE positions have been approved, whereas in critical needs specialties (needed to support rural/underserved healthcare and improve specialty access) 256.5 FTE positions have been added.

Discussion

There are several important desired short-term outcomes from VACAA. The first is improved access to high-quality care for both rural and urban veterans. There is an emphasis on primary care and mental health because shortages in these areas across the U.S. are well established.3,4,10 Likewise, rural areas have been prioritized because often there is a disparity of care.

One area of concern is the small number of applicants in geriatrics. Even with VACAA specifically targeting geriatrics as a primary care specialty, we have only received enough applications to approve 6.3 positions over the first 3 years of the program. As the veteran and overall population in the U.S. ages, it is important to develop a medical workforce that is willing and able to address their needs.

The VACAA statute is not intended to alter medical students’ career choice but rather to provide funded positions for those choosing primary care, geriatrics, psychiatry (including psychiatric subspecialties), and experience in the VA clinical settings. The hope is that this experience will encourage practitioners to competently care for veterans after training in the VA and/or other civilian settings.

By enabling smaller VA facilities to become training sites through planning and infrastructure grants, residents have the opportunity to gain experience in more rural settings. Physicians who choose to train in rural areas are likely to spend time practicing in those areas after they complete training.15 The process of developing facilities with no GME into training sitestakes time and resources. Establishing an education office and choosing site directors and core faculty are all important steps that must be done before resident rotations begin. Resources provided through VACAA have enabled the VHA to reduce the number of VAMCs with no GME activity to just 3.

Another benefit of VACAA GME expansion is the opportunity to engage new LCME/AOA-accredited medical schools and ACGME/AOA-accredited residency-sponsoring institutions.16,17 Representatives of these institutions may have perceived a reluctance of their local VAs to develop GME affiliations in the past. This statute has enabled many VAMCs to use nontraditional training sites and modalities to overcome barriers and create new academic affiliations.

However, VACAA only provides funds for training that occurs in established VA sites of care. This can hinder the development of partnerships where other funding sources are required for non-VA rotations. Another VACAA limitation is that it does not fund undergraduate medical education as does the Armed Forces Health Professional Scholarship Program (HPSP). In addition, the primary financial relationship is between the VA and the sponsoring institution, thus VHA cannot send residents to underserved locations.

Conclusion

The VHA has a rich tradition of educating physician and other health care providers in the U.S. More than 60% of U.S. trained physicians received a portion of their training through VHA.2 Through VACAA GME expansion initiative, the 113th Congress has asked VHA to continue its important training mission “to bind up the Nations wounds” and “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.”18

Acknowledgments

In memoriam – Robert Louis Jesse MD, PhD. Dr. Jesse, the Chief of the Office of Academic Affiliations passed away on September 2, 2017, at age 64. He had an illustrious medical career as a cardiologist and served in many leadership roles including Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His expertise, visionary leadership, and friendship will be missed by all involved in the VA’s academic training mission but particularly by those of us who worked for and with him at OAA.

1. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Policy Memorandum No. 2. Policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf. Published January 30, 1947. Accessed December 13, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www .va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2018.

3. IHS, Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand 2016 update: projections from 2014 to 2025, final report. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2017.

4. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-114.

5. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America 2011-2015. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publica tions/2017/acs/acs-36.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

6. Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Wang S, Lee A, Kazis LE. Rural-urban disparities in health-related quality of life within disease categories of veterans. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):204-211.

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO-18-124. VHA Physician Staffing and Recruitment. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687853.pdf. Published October 19, 2017. Accessed January 23, 2018.

8. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, section 301 (b): Increase of graduate medical education residency positions, 38 USC § 74 (2014) .

9. Jeff Miller and Richard Blumenthal Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2016, 38 USC §101 (2016).

10. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328.

11. Garibaldi RA, Popkave C, Bylsma W. Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):507-512.

12. West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247.

13. Stimmel B, Haddow S, Smith L. The practice of general internal medicine by subspecialists. J Urban Health. 1998;75(1):184-190.

14. Shea JA, Kleetke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37(4):333-338.

15. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Paynter NP. Critical factors for designing

16. Accredited MD programs in the United States. http://lcme.org /directory/accredited-u-s-programs/. Updated December 12, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

17. Osteopathic medical schools. http://www.osteopathic.org/in side-aoa/about/affiliates/Pages/osteopathic-medical-schools.aspx Published 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

18. Lincoln A. Second inaugural address. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/vamotto.pdf. Accessed January 8. 2018.

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution

To distribute these newly created GME positions as mandated by Congress, the OAA is using a system with 3 types of request for proposal (RFP) applications. These include planning, infrastructure, and position grants. This phased approach was taken with the understanding that the development of new training sites requires a properly staffed education office and dedicated faculty time. Planning and infrastructure grants provide start-up funds for smaller VAMCs, allowing them to keep facility resources focused on their clinical mission.

Planning grants (of up to $250,000 over 2 years) primarily were designed for VA facilities with no or low numbers of physician residents at the desired teaching location. Priority was given to facilities in rural and/or underserved areas as well as those developing new affiliations. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with peer-selected Designated Education Officers (DEOs) from VA facilities across the nation that were not applying for the grants. Awards were based on the priorities mentioned earlier, with additional credit for programs focused on 2 VHA fundamental services areas—primary care and/or mental health training. Facilities receiving planning grants were mentored by an OAA physician staff member, anticipating a 2- to 3-year time line to request positions and begin GME training.

Infrastructure grants (of up to $520,000 used over 2-3 years) were designed as bridge funds after approval of Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) GME positions. Infrastructure grants are appropriate to sustain a local education office, develop VA faculty, purchase equipment, and make minor modifications to the clinical space in the VAMCs or CBOCs to enhance the learning environment during the period before VA supportive funds from the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) (similar to indirect GME funds from CMS) become available. Applications were managed the same as planning grant submissions.

Position RFPs, unlike planning and infrastructure RFPs, are available to all VAMCs. The primary purpose of the VACAA Position RFP is to fund new positions in primary care and psychiatry. Graduate medical education positions in subspecialty programs also are considered when there is documentation of critical need to improve access to these services. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with selected DEOs from VA facilities around the U.S. Award criteria prioritized primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics), and mental health (psychiatry and psychiatry subspecialties). Priority also was given to positions in areas with a documented shortage of physicians and areas with high concentrations of veterans.

Current Progress

To date the OAA has offered 3 RFP cycles consisting of planning/infrastructure grants, and 4 RFP cycles for salary/benefit support for additional resident full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Resident positions were defined as residency or fellowship FTEs that were part of an ACGME or AOA-accredited training program. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of awarded GME positions.

In primary care specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics, a total of 349.4 FTE positions have been approved (Table 1). Due to a low number of applications, only 6.3 of these positions were awarded in geriatrics. In mental health, 167.6 FTE positions have been approved, whereas in critical needs specialties (needed to support rural/underserved healthcare and improve specialty access) 256.5 FTE positions have been added.

Discussion

There are several important desired short-term outcomes from VACAA. The first is improved access to high-quality care for both rural and urban veterans. There is an emphasis on primary care and mental health because shortages in these areas across the U.S. are well established.3,4,10 Likewise, rural areas have been prioritized because often there is a disparity of care.

One area of concern is the small number of applicants in geriatrics. Even with VACAA specifically targeting geriatrics as a primary care specialty, we have only received enough applications to approve 6.3 positions over the first 3 years of the program. As the veteran and overall population in the U.S. ages, it is important to develop a medical workforce that is willing and able to address their needs.

The VACAA statute is not intended to alter medical students’ career choice but rather to provide funded positions for those choosing primary care, geriatrics, psychiatry (including psychiatric subspecialties), and experience in the VA clinical settings. The hope is that this experience will encourage practitioners to competently care for veterans after training in the VA and/or other civilian settings.

By enabling smaller VA facilities to become training sites through planning and infrastructure grants, residents have the opportunity to gain experience in more rural settings. Physicians who choose to train in rural areas are likely to spend time practicing in those areas after they complete training.15 The process of developing facilities with no GME into training sitestakes time and resources. Establishing an education office and choosing site directors and core faculty are all important steps that must be done before resident rotations begin. Resources provided through VACAA have enabled the VHA to reduce the number of VAMCs with no GME activity to just 3.

Another benefit of VACAA GME expansion is the opportunity to engage new LCME/AOA-accredited medical schools and ACGME/AOA-accredited residency-sponsoring institutions.16,17 Representatives of these institutions may have perceived a reluctance of their local VAs to develop GME affiliations in the past. This statute has enabled many VAMCs to use nontraditional training sites and modalities to overcome barriers and create new academic affiliations.

However, VACAA only provides funds for training that occurs in established VA sites of care. This can hinder the development of partnerships where other funding sources are required for non-VA rotations. Another VACAA limitation is that it does not fund undergraduate medical education as does the Armed Forces Health Professional Scholarship Program (HPSP). In addition, the primary financial relationship is between the VA and the sponsoring institution, thus VHA cannot send residents to underserved locations.

Conclusion

The VHA has a rich tradition of educating physician and other health care providers in the U.S. More than 60% of U.S. trained physicians received a portion of their training through VHA.2 Through VACAA GME expansion initiative, the 113th Congress has asked VHA to continue its important training mission “to bind up the Nations wounds” and “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.”18

Acknowledgments

In memoriam – Robert Louis Jesse MD, PhD. Dr. Jesse, the Chief of the Office of Academic Affiliations passed away on September 2, 2017, at age 64. He had an illustrious medical career as a cardiologist and served in many leadership roles including Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His expertise, visionary leadership, and friendship will be missed by all involved in the VA’s academic training mission but particularly by those of us who worked for and with him at OAA.

The VHA is the largest healthcare delivery system in the U.S. It includes 146 medical centers (VAMCs), 1,063 community-based outpatient centers (CBOCs) and various other sites of care. General Omar Bradley, the first VA Secretary, established education as one of VA’s 4 statutory missions in Policy Memorandum No.2.1 In addition to training physicians to care for active-duty service members and veterans, 38 USC §7302 directs the VA to assist in providing an adequate supply of health personnel. The 4 statutory missions of the VA are inclusive of not only developing, operating, and maintaining a health care system for veterans, but also including contingency support services as part of emergency preparedness, conducting research, and offering a program of education for health professions.

Background

Today, with few exceptions, the VHA does not act as a graduate medical education (GME) sponsoring institution. Through its Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA), the VHA develops partnerships with Liaison Committee for Medical Education (LCME)/American Osteopathic Association (AOA)-approved medical colleges/universities and with institutions that sponsor Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)/AOA-accredited residency program-sponsoring institutions. These collaborations include 144 out of 149 allopathic medical schools and all 34 osteopathic medical schools. The VHA provided training to 43,565 medical residents and 24,683 medical students through these partnerships in 2017.2 Since funding of the GME positions is not provided through the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), program sponsors may use these partnerships to expand GME positions beyond their funding (but not ACGME) cap.

The gap between supply and demand of physicians continues to grow nationally.3,4 This gap is particularly significant in rural and other underserved areas. U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 5 million veterans (24%) live in rural areas.5 Compared with the urban veteran population, the rural veteran experiences higher disease prevalence and lower physical and mental quality-of-life scores.6 Addressing the problem of physician shortages is a mission-critical priority for the VHA.7

With an eye toward enhancing 2 of the 4 statutory missions of the VA and to mitigate the shortage of physicians and improve the access of veterans to VHA medical services, on August 7, 2014, the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014 (Public Law [PL] 113-146), known as the Choice Act was enacted.8 Title III, §301(b) of the Choice Act requires VHA to increase GME residency positions by:

Establishing new medical residency programs, or ensuring that already established medical residency programs have a sufficient number of residency positions, at any VHA medical facility that is: (a) experiencing a shortage of physicians and (b) located in a community that is designated as a health professional shortage area.

The legislation specifies that priority must be placed on medical occupations that experience the largest staffing shortages throughout the VHA and “programs in primary care, mental health, and any other specialty that the Secretary of the VA determines appropriate.” The Choice Act authorized the VHA to increase the number of GME residency positions by up to 1,500 over a 5-year period. In December 2016, as amended by PL 114–315, Title VI, §617(a), this authorization was extended by another 5 years for a total of 10 years and will run through 2024.9

GME Development/Distribution

To distribute these newly created GME positions as mandated by Congress, the OAA is using a system with 3 types of request for proposal (RFP) applications. These include planning, infrastructure, and position grants. This phased approach was taken with the understanding that the development of new training sites requires a properly staffed education office and dedicated faculty time. Planning and infrastructure grants provide start-up funds for smaller VAMCs, allowing them to keep facility resources focused on their clinical mission.

Planning grants (of up to $250,000 over 2 years) primarily were designed for VA facilities with no or low numbers of physician residents at the desired teaching location. Priority was given to facilities in rural and/or underserved areas as well as those developing new affiliations. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with peer-selected Designated Education Officers (DEOs) from VA facilities across the nation that were not applying for the grants. Awards were based on the priorities mentioned earlier, with additional credit for programs focused on 2 VHA fundamental services areas—primary care and/or mental health training. Facilities receiving planning grants were mentored by an OAA physician staff member, anticipating a 2- to 3-year time line to request positions and begin GME training.

Infrastructure grants (of up to $520,000 used over 2-3 years) were designed as bridge funds after approval of Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act (VACAA) GME positions. Infrastructure grants are appropriate to sustain a local education office, develop VA faculty, purchase equipment, and make minor modifications to the clinical space in the VAMCs or CBOCs to enhance the learning environment during the period before VA supportive funds from the Veterans Equitable Resource Allocation (VERA) (similar to indirect GME funds from CMS) become available. Applications were managed the same as planning grant submissions.

Position RFPs, unlike planning and infrastructure RFPs, are available to all VAMCs. The primary purpose of the VACAA Position RFP is to fund new positions in primary care and psychiatry. Graduate medical education positions in subspecialty programs also are considered when there is documentation of critical need to improve access to these services. Applications were reviewed by OAA staff along with selected DEOs from VA facilities around the U.S. Award criteria prioritized primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, geriatrics), and mental health (psychiatry and psychiatry subspecialties). Priority also was given to positions in areas with a documented shortage of physicians and areas with high concentrations of veterans.

Current Progress

To date the OAA has offered 3 RFP cycles consisting of planning/infrastructure grants, and 4 RFP cycles for salary/benefit support for additional resident full-time equivalent (FTE) positions. Resident positions were defined as residency or fellowship FTEs that were part of an ACGME or AOA-accredited training program. Figure 1 illustrates the geographic distribution of awarded GME positions.

In primary care specialties (family medicine, internal medicine, and geriatrics, a total of 349.4 FTE positions have been approved (Table 1). Due to a low number of applications, only 6.3 of these positions were awarded in geriatrics. In mental health, 167.6 FTE positions have been approved, whereas in critical needs specialties (needed to support rural/underserved healthcare and improve specialty access) 256.5 FTE positions have been added.

Discussion

There are several important desired short-term outcomes from VACAA. The first is improved access to high-quality care for both rural and urban veterans. There is an emphasis on primary care and mental health because shortages in these areas across the U.S. are well established.3,4,10 Likewise, rural areas have been prioritized because often there is a disparity of care.

One area of concern is the small number of applicants in geriatrics. Even with VACAA specifically targeting geriatrics as a primary care specialty, we have only received enough applications to approve 6.3 positions over the first 3 years of the program. As the veteran and overall population in the U.S. ages, it is important to develop a medical workforce that is willing and able to address their needs.

The VACAA statute is not intended to alter medical students’ career choice but rather to provide funded positions for those choosing primary care, geriatrics, psychiatry (including psychiatric subspecialties), and experience in the VA clinical settings. The hope is that this experience will encourage practitioners to competently care for veterans after training in the VA and/or other civilian settings.

By enabling smaller VA facilities to become training sites through planning and infrastructure grants, residents have the opportunity to gain experience in more rural settings. Physicians who choose to train in rural areas are likely to spend time practicing in those areas after they complete training.15 The process of developing facilities with no GME into training sitestakes time and resources. Establishing an education office and choosing site directors and core faculty are all important steps that must be done before resident rotations begin. Resources provided through VACAA have enabled the VHA to reduce the number of VAMCs with no GME activity to just 3.

Another benefit of VACAA GME expansion is the opportunity to engage new LCME/AOA-accredited medical schools and ACGME/AOA-accredited residency-sponsoring institutions.16,17 Representatives of these institutions may have perceived a reluctance of their local VAs to develop GME affiliations in the past. This statute has enabled many VAMCs to use nontraditional training sites and modalities to overcome barriers and create new academic affiliations.

However, VACAA only provides funds for training that occurs in established VA sites of care. This can hinder the development of partnerships where other funding sources are required for non-VA rotations. Another VACAA limitation is that it does not fund undergraduate medical education as does the Armed Forces Health Professional Scholarship Program (HPSP). In addition, the primary financial relationship is between the VA and the sponsoring institution, thus VHA cannot send residents to underserved locations.

Conclusion

The VHA has a rich tradition of educating physician and other health care providers in the U.S. More than 60% of U.S. trained physicians received a portion of their training through VHA.2 Through VACAA GME expansion initiative, the 113th Congress has asked VHA to continue its important training mission “to bind up the Nations wounds” and “to care for him who shall have borne the battle.”18

Acknowledgments

In memoriam – Robert Louis Jesse MD, PhD. Dr. Jesse, the Chief of the Office of Academic Affiliations passed away on September 2, 2017, at age 64. He had an illustrious medical career as a cardiologist and served in many leadership roles including Principal Deputy Under Secretary for Health in the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. His expertise, visionary leadership, and friendship will be missed by all involved in the VA’s academic training mission but particularly by those of us who worked for and with him at OAA.

1. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Policy Memorandum No. 2. Policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf. Published January 30, 1947. Accessed December 13, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www .va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2018.

3. IHS, Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand 2016 update: projections from 2014 to 2025, final report. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2017.

4. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-114.

5. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America 2011-2015. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publica tions/2017/acs/acs-36.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

6. Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Wang S, Lee A, Kazis LE. Rural-urban disparities in health-related quality of life within disease categories of veterans. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):204-211.

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO-18-124. VHA Physician Staffing and Recruitment. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687853.pdf. Published October 19, 2017. Accessed January 23, 2018.

8. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, section 301 (b): Increase of graduate medical education residency positions, 38 USC § 74 (2014) .

9. Jeff Miller and Richard Blumenthal Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2016, 38 USC §101 (2016).

10. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328.

11. Garibaldi RA, Popkave C, Bylsma W. Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):507-512.

12. West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247.

13. Stimmel B, Haddow S, Smith L. The practice of general internal medicine by subspecialists. J Urban Health. 1998;75(1):184-190.

14. Shea JA, Kleetke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37(4):333-338.

15. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Paynter NP. Critical factors for designing

16. Accredited MD programs in the United States. http://lcme.org /directory/accredited-u-s-programs/. Updated December 12, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

17. Osteopathic medical schools. http://www.osteopathic.org/in side-aoa/about/affiliates/Pages/osteopathic-medical-schools.aspx Published 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

18. Lincoln A. Second inaugural address. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/vamotto.pdf. Accessed January 8. 2018.

1. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. Policy Memorandum No. 2. Policy in association of veterans’ hospitals with medical schools. https://www.va.gov/oaa/Archive/PolicyMemo2.pdf. Published January 30, 1947. Accessed December 13, 2017.

2. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, Office of Academic Affiliations. 2017 statistics: health professions trainees. https://www .va.gov/OAA/docs/OAA_Statistics.pdf. Accessed January 8, 2018.

3. IHS, Inc. The complexities of physician supply and demand 2016 update: projections from 2014 to 2025, final report. https://www.aamc.org/download/458082/data/2016_complexities_of_supply_and_demand_projections.pdf. Published April 5, 2016. Accessed December 13, 2017.

4. Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Tran C, Bazemore AW. Estimating the residency expansion required to avoid projected primary care physician shortages by 2035. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):107-114.

5. Holder KA. Veterans in rural America 2011-2015. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publica tions/2017/acs/acs-36.pdf. Published January 2017. Accessed January 18, 2018.

6. Weeks WB, Wallace AE, Wang S, Lee A, Kazis LE. Rural-urban disparities in health-related quality of life within disease categories of veterans. J Rural Health. 2006;22(3):204-211.

7. U.S. Government Accountability Office. GAO-18-124. VHA Physician Staffing and Recruitment. https://www.gao.gov/assets/690/687853.pdf. Published October 19, 2017. Accessed January 23, 2018.

8. Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act, section 301 (b): Increase of graduate medical education residency positions, 38 USC § 74 (2014) .

9. Jeff Miller and Richard Blumenthal Veterans Health Care and Benefits Improvement Act of 2016, 38 USC §101 (2016).

10. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Holzer CE, Morrissey JP. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1323-1328.

11. Garibaldi RA, Popkave C, Bylsma W. Career plans for trainees in internal medicine residency programs. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):507-512.

12. West CP, Dupras DM. General medicine vs subspecialty career plans among internal medicine residents. JAMA. 2012;308(21):2241-2247.

13. Stimmel B, Haddow S, Smith L. The practice of general internal medicine by subspecialists. J Urban Health. 1998;75(1):184-190.

14. Shea JA, Kleetke PR, Wozniak GD, Polsky D, Escarce JJ. Self-reported physician specialties and the primary care content of medical practice: a study of the AMA physician masterfile. American Medical Association. Med Care. 1999;37(4):333-338.

15. Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Paynter NP. Critical factors for designing

16. Accredited MD programs in the United States. http://lcme.org /directory/accredited-u-s-programs/. Updated December 12, 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

17. Osteopathic medical schools. http://www.osteopathic.org/in side-aoa/about/affiliates/Pages/osteopathic-medical-schools.aspx Published 2017. Accessed January 8, 2018.

18. Lincoln A. Second inaugural address. https://www.va.gov/opa/publications/celebrate/vamotto.pdf. Accessed January 8. 2018.