User login

Strategies and steps for the surgical management of endometriosis

- Resection of an endometrioma in severe disease, using a “stripping” technique

- Ovarian cystectomy

- Resection of endometriosis from the left ligament

- Resection of endometriosis on the bladder

These videos were provided by Anthony Luciano, MD.

Endometriosis affects 7% to 10% of women in the United States, mostly during reproductive years.1 The estimated annual cost for managing the approximately 10 million affected women? More than $17 billion.2 The added cost of this chronic disease, with recurrences of pain and infertility, comes in the form of serious life disruption, emotional suffering, marital and social dysfunction, and diminished productivity.

Although the prevalence of endometriosis is highest during the third and fourth decades of life, the disease is also common in adolescent girls. Indeed, 45% of adolescents who have chronic pelvic pain are found to have endometriosis; if their pain does not respond to an oral contraceptive (OC) or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, 70% are subsequently found at laparoscopy to have endometriosis.3

What is it?

Endometriosis is the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus, such as eutopic endometrium. The disease responds to effects of cyclic ovarian hormones, proliferating and bleeding with each menstrual cycle, which often leads to diffuse inflammation, adhesions, and growth of endometriotic nodules or cysts (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Drainage will not suffice

Surgical management of ovarian endometriomas must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.Symptoms tend to reflect affected organs:

- Because the pelvic organs are most often involved, the classic symptom triad of the disease comprises dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.

- Urinary urgency, dysuria, dyschezia, and tenesmus are frequent complaints when the bladder or rectosigmoid is involved.

- When distant organs are affected, such as the upper abdomen, diaphragm, lungs, and bowel, the patient may complain of respiratory symptoms, hemoptysis, pneumothorax, shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, and episodic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

The hallmark of endometriosis is catamenial symptoms, which are usually cyclic and most severe around the time of menses. Clinical signs include palpable tender nodules and fibrosis on the anterior and posterior cul de sac, fixed retroverted or anteverted uterus, and adnexal cystic masses.

Because none of these symptoms or signs is specific for endometriosis, diagnosis relies on laparoscopy, which allows the surgeon to:

- visualize it in its various appearances and locations (FIGURE 2)

- confirm the diagnosis histologically with directed excisional biopsy

- treat it surgically with either excision or ablation.

In this article, we describe various surgical techniques for the management of endometriosis. Beyond resection or ablation of lesions, however, your care should also be directed to postoperative measures to prevent its recurrence and to avoid repeated surgical interventions—which, regrettably, are much too common in women who are afflicted by this enigmatic disease.

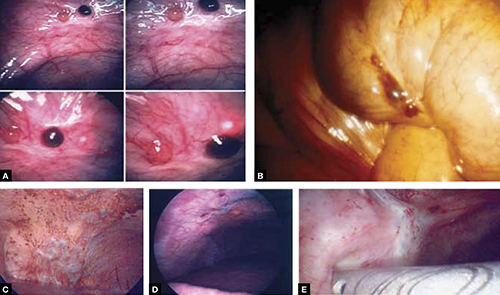

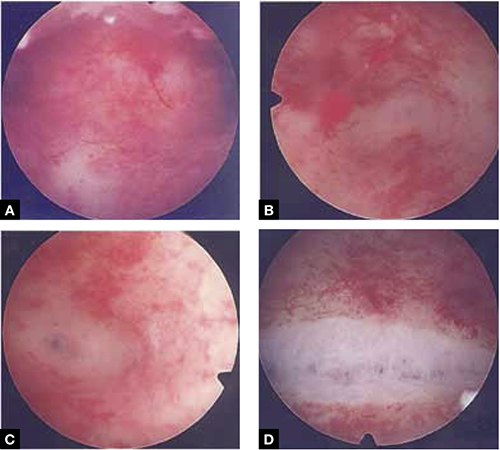

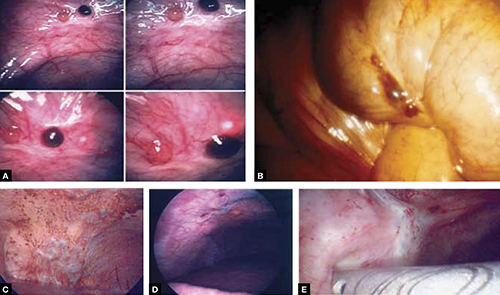

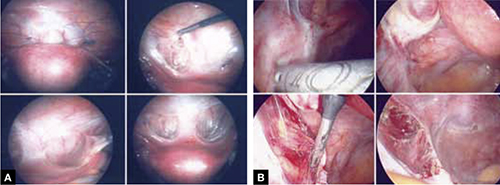

FIGURE 2 Endometriosis: A disease of varying appearance

Lesions of endometriosis can be pink, dark, clear, or white on the pelvic sidewall (A), bowel (B), and diaphragm (C); under the rib cage (D); and on the ureter (E) (left ureter shown here).

CASE Severe disease in a young woman

S. D. is a 22-year-old unmarried nulligravida who came to the emergency service complaining of acute onset of severe low abdominal pain, which developed while she was running. She was afebrile and in obvious distress, with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness and guarding, especially on the left side.

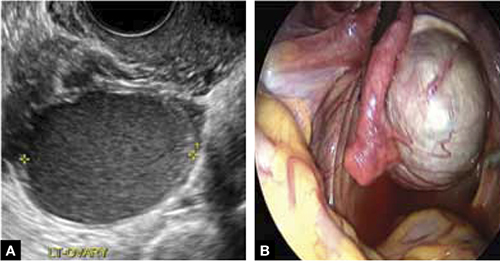

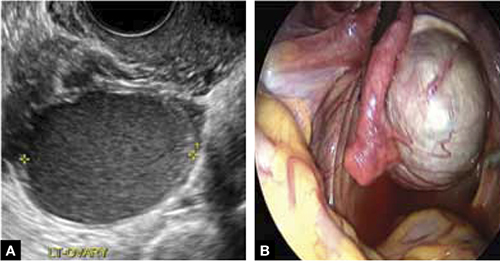

Ultrasonography revealed a 7-cm adnexal cystic mass suggestive of endometrioma (FIGURE 3).

Two years before this episode, S. D. underwent laparoscopic resection of a 5-cm endometrioma on the right ovary. Subsequently, she was treated with a cyclic OC, which she discontinued after 1 year because she was not sexually active.

The family history is positive for endometriosis in her mother, who had undergone multiple laparoscopic investigations and, eventually, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at 40 years of age.

S. D. was treated on the emergency service with analgesics and referred to you for surgical management.

S. D. has severe disease that requires aggressive surgical resection and a lifelong management plan. That plan includes liberal use of medical therapy to prevent recurrence of symptoms and avoid repeated surgical procedures—including the total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy that her mother underwent.

What is the best immediate treatment plan? Should you:

- drain the cyst?

- drain it and coagulate or ablate its wall?

- resect the wall of the cyst?

- perform salpingo-oophorectomy?

You also ask yourself: What is the risk of recurrence of endometrioma and its symptoms after each of those treatments? And how can I reduce those risks?

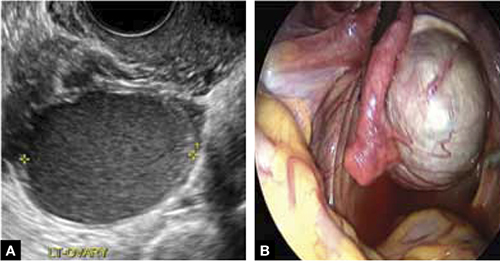

FIGURE 3 Endometrioma

Endometrioma on ultrasonography (A), with its characteristic homogeneous, echogenic appearance and “ground glass” pattern, and through the laparoscope (B). These images are from the patient whose case is described in the text.

Focal point: Ovary

The ovary is the most common organ affected by endometriosis. The presence of ovarian endometriomas, in 17% to 44% of patients who have this disease,4 is often associated with an advanced stage of disease.

In a population of 1,785 patients who were surgically treated for ovarian endometriosis, Redwine reported that only 1% had exclusively ovarian involvement; 99% also had diffuse pelvic disease,5 suggesting that ovarian endometrioma is a marker of extensive disease, which often requires a gynecologic surgeon who has advanced skills and experience in the surgical management of severe endometriosis.

Simple drainage is inadequate

Surgical management of ovarian endometrioma must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.6 The currently accepted surgical management of endometrioma involves either 1) coagulation and ablation of the wall of the cyst with electrosurgery or laser or 2) removal of the cyst wall from the ovary with blunt and sharp dissection.

Several studies have compared these two techniques, but only two7,8 were prospectively randomized.

Study #1. Beretta and co-workers7 studied 64 patients who had ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm and randomized them to cystectomy by complete stripping of the cyst wall or to drainage of fluid followed by electrocoagulation to ablate the endometriosis lesions within the cyst wall. The two groups were followed for 2 years to assess the recurrence of symptoms and the pregnancy rate in the patients who were infertile.

Recurrence of symptoms and the need for medical or surgical intervention occurred with less frequency and much later in the resection group than in the ablation group: 19 months, compared to 9.5 months, postoperatively. The cumulative pregnancy rate 24 months postoperatively was also much higher in the resection group (66.7%) than in the ablative group (23.5%).

Study #2. In a later study,8 Alborzi and colleagues randomized 100 patients who had endometrioma to cystectomy or to drainage and coagulation of the cyst wall. The mean recurrence rate, 2 years postoperatively, was much lower in the excision group (15.8%) than in the ablative group (56.7%). The cumulative pregnancy rate at 12 months was higher in the excision group (54.9%, compared to 23.3%). Furthermore, the reoperation rate at 24 months was much lower in the excision group (5.8%) than in the ablative group (22.9%).

These favorable results for cystectomy over ablation were validated by a Cochrane Review, which concluded that excision of endometriomas is the preferred approach because it provides 1) a more favorable outcome than drainage and ablation, 2) lower rates of recurrence of endometriomas and symptoms, and 3) a much higher spontaneous pregnancy rate in infertile women.9

Although resection of the cyst wall is technically more challenging and takes longer to perform than drainage and ablation, we exclusively perform resection rather than ablation of endometriomas because we believe that more lasting therapeutic effects and reduced recurrence of symptoms and disease justify the extra effort and a longer procedure.

Drawback of cystectomy

A potential risk of cystectomy is that it can diminish ovarian reserve and, in rare cases, induce premature menopause, which can be devastating for women whose main purpose for having surgery is to restore or improve their fertility.

The impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve was prospectively studied by Chang and co-workers,10 who measured preoperative and postoperative levels of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) in 13 women who had endometrioma, 6 who had mature teratoma, and 1 who had mucinous cystadenoma. One week postoperatively, the AMH level decreased significantly overall in all groups. At 4 and 12 weeks postoperatively, however, the AMH level returned to preoperative levels among subjects in the non-endometrioma group but not among subjects who had endometrioma; rather, their level remained statistically lower than the preoperative level during the entire 3 months of follow-up.

Stripping the wall of an endometrioma cyst is more difficult than it is for other benign cysts, such as cystic teratoma or cystadenoma, in which there usually is a well-defined dissection plane between the wall of the cyst and surrounding stromal tissue—allowing for easy and clean separation of the wall. The cyst wall of an endometrioma, on the other hand, is intimately attached to underlying ovarian stroma; lack of a clear cleavage plane between cyst and ovarian stroma often results in unintentional removal of layers of ovarian cortex with underlying follicles, which, in turn, may lead to a reduction in ovarian reserve.

Histologic analyses of resected endometrioma cyst walls have reported follicle-containing ovarian tissue attached to the stripped cyst wall in 54% of cases.11,12 That observation explains why, and how, ovarian reserve can be compromised after resection of endometrioma.

Further risk: Ovarian failure

In rare cases, excision of endometriomas results in complete ovarian failure, described by Busacca and colleagues, who reported three cases of ovarian failure (2.4%) after resection of bilateral endometriomas in 126 patients.13 They attributed ovarian failure to excessive cauterization that compromised vascularization, as well as to excessive removal of ovarian tissue.

It is important, therefore, to strip the thinnest layer of the cyst capsule and to reduce the amount of electrocoagulation of ovarian stroma as much as possible to safeguard functional ovarian tissue.

CASE continued

S. D. was scheduled for laparoscopy to remove the endometrioma and other concurrent pelvic and peritoneal pathology, such as endometriosis and pelvic adhesions. You also scheduled her for hysteroscopy to evaluate the endometrial cavity for potential pathology, such as endometrial polyps and uterine septum, which appear to be more common in women who have endometriosis.

Nawroth and co-workers14 found a much higher incidence of endometriosis in patients who had a septate uterus. Metalliotakis and co-workers15 found congenital uterine malformations to be more common in patients who had endometriosis, compared with controls; uterine septum was, by far, the most common anomaly.

CASE continued

Hysteroscopy revealed a small and broad septum, which was resected sharply with hysteroscopic scissors (FIGURE 4). Laparoscopy revealed a 7-cm endometrioma on the left ovary, with adhesions to the posterior broad ligament and pelvic sidewall. S. D. also had deep implants of endometriosis on the left pelvic sidewall, the posterior cul de sac, the right pelvic sidewall, and the right ovary, which was cohesively adherent to the ovarian fossa.

As you expected, S. D. has stage-IV disease, according to the revised American Fertility Society Classification.

Following adhesiolysis, the endometrioma was resected (see VIDEO 1). Because of the large ovarian defect, the edges of the ovary were approximated with imbricating running 3-0 Vicryl suture. Deep endometriosis was also resected. Superficial endometriosis was peeled off or coagulated using bipolar forceps.

Note: Alternatively, and with comparable results, resection may be performed with a laser or other energy source. We prefer resection, rather than ablation, of deep endometriosis, but no data exists to support one technique over the other.

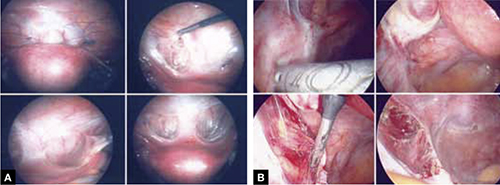

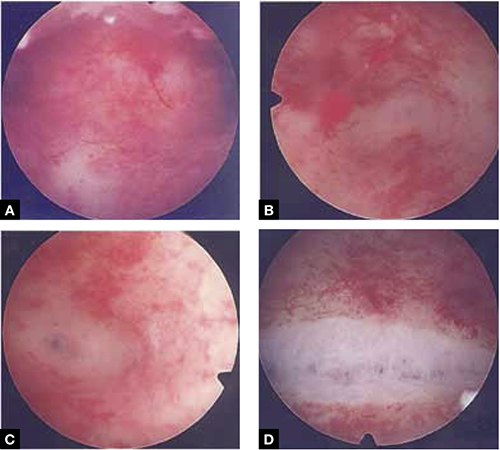

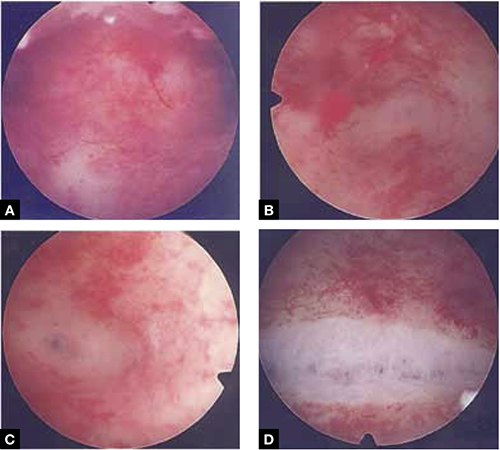

FIGURE 4 Septate uterus with deep cornua

Through the hysteroscope, a shallow septum is visible at the fundus of the uterus, dividing the upper endometrial cavity into two chambers (A), with deep cornua on the left (B) and right (C). Normal fundal anatomy is restored by septolysis along the avascular plane (D).

Technique: How we resect endometrioma

In removing endometrioma (see VIDEO 2), it is important to grasp the thinnest part of the cyst wall and progressively strip it, to avoid removing excess ovarian tissue and to reduce the risk of compromising ovarian reserve.

After draining the endometrioma of its chocolate-colored fluid, we irrigate and drain the cyst several times with warm lactated Ringers’ solution to promote separation of the cyst wall from underlying stroma and better identify the dissection plane. The cyst wall is inspected by introducing the laparoscope into the cyst to examine its surface, which is often laden with implants of deep and superficial endometriosis.

If we cannot easily identify the plane of dissection along the edges, we may evert the cyst and make an incision at its base to create a wedge between the wall of the cyst and underlying stroma. The edge of the incised wall is then grasped and retracted to create a space between the wall and the underlying stroma, from which it is progressively stripped from the ovary.

Traction and counter-traction are the hallmarks of dissection here; sometimes, we use laparoscopic scissors to sharply resect the ovarian stromal attachments that adhere cohesively to the cyst wall. This technique is continued until the entire cyst wall is removed. When follicle-containing ovarian tissue remains attached to the cyst wall, we introduce the closed tips of the Dolphin forceps between the cyst wall and adjacent follicle-containing stroma, spread the tips apart, and recover the true plane of dissection between the thin wall of the cyst and stroma.

After the wall of the cyst is removed, the ovarian crater invariably bleeds because blood vessels supplying the wall have been separated and opened. Utilizing warm lactated Ringers’ solution, we copiously irrigate the bleeding ovarian stroma to identify each bleeding vessel and, by placing the tips of the micro-bipolar forceps on either side of the bleeder, individually coagulate each vessel, thus inflicting minimal thermal damage to the surrounding stroma.

Pearl. Avoid using Kleppinger forceps to indiscriminately coagulate the bloody stroma in the crater created after the cystectomy, because doing so can result in excessive destruction of ovarian tissue or inadvertent coagulation of hylar vessels that would interrupt the blood supply to the ovary, compromising its function.16

Suturing. Some surgeons find that fenestration, drainage, and coagulation of the cyst wall is acceptable, but we have concerns not only about incomplete ablation of the endometriosis on the cyst wall, which may be responsible for the higher recurrence rate of disease, but also about the risk of thermal injury to underlying follicles, which may compromise ovarian reserve.16

Hemostasis. Once complete hemostasis has been achieved, the decision to approximate (or not) the edges, preferably with fine absorbable suture, is based on how large the defect is and whether or not the edges of the crater spontaneously come together. For large craters, we usually close the ovary with a 3-0 or 4-0 Vicryl continuous suture, imbricating the edges to expose as little suture material as possible to reduce postoperative formation of adhesions, which is common after ovarian surgery.17

Last, we ensure that hemostasis is present. Often we apply an anti-adhesion solution, such as icodextrin 4% (Adept). This agent has been shown to reduce postoperative adhesion formation, especially after laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.18

A high level of skill is needed

Ovarian endometriomas signal advanced disease; advanced surgical skills are required to treat them adequately. Simple drainage is of little therapeutic value and should seldom be considered a treatment option. Although drainage plus ablation of the cyst wall ameliorates symptoms, excision of endometriomas should be considered preferable because it provides a more favorable outcome, a lower risk of recurrence of endometriomas and symptoms, and a higher rate of spontaneous pregnancy in previously infertile women.7-9

To recap, we advise the surgeon to:

- Manage ovarian endometriomas with resection of the entire cyst wall, grasping and stripping the thinnest layer of the cyst wall without removing underlying functional ovarian stroma.

- Avoid excessive cauterization of the underlying ovarian stroma by utilizing micro-bipolar forceps and applying energy only around bleeding vessels.

- Close stromal defects, when the crater is large and its edges do not spontaneously come together, by approximating the edges with an imbricating resorbable suture.

CASE continued

As in most cases of advanced endometriosis, S. D. also had diffuse implants of deep and superficial endometriosis on the peritoneum of the pelvic sidewalls and on the anterior and posterior cul de sac.

Should you ablate or resect these lesions? Are there advantages to either approach?

Ablation of endometriosis implants may involve either electrocoagulation of the lesion with bipolar energy or laser vaporization/coagulation, which destroys or devitalizes active endometriosis but does not actually remove the lesion. Ablation destroys the lesion without getting a specimen for histologic diagnosis.

Resection of endometriosis implants involves complete removal of the lesion from its epithelial surface to the depth of its base. Resection can be performed with scissors, laser, or monopolar electrosurgery. Resection removes the lesion in its entirety, yielding a histologic diagnosis and allowing you to determine whether, indeed, the entire specimen has been removed.

The question of what is more effective—ablating or resecting endometriosis implants?—was addressed in a prospective study in which 141 patients with endometriosis-related pain were randomized at laparoscopic surgery to either excision or ablation/coagulation of endometriosis lesions.19 Six months postoperatively, the pain score decreased by, on average, 11.2 points in the excision group and 8.7 points in the coagulation/ablative group.

Because the difference in those average pain scores was not statistically significant, however, investigators concluded that the techniques are comparable, with similar efficacy. That interpretation has been criticized because the study was underpowered and included only patients who had mild endometriosis—leaving open the possibility that deep endometriosis may not be adequately treated by electrocoagulation or ablation.

In contrast to superficial endometriosis, which may respond similarly to ablation or resection, deep endometriosis is difficult to ablate either with electrosurgery or a laser because the energy cannot reach deeper layers and active disease is therefore likely to be left behind. Moreover, when endometriosis overlies vital structures, such as the ureter or bowel, ablation of the lesion may cause thermal damage to the underlying organ, and such damage may not manifest until several days later, when the patient experiences, say, urinary leakage in the peritoneum or symptoms of bowel perforation.

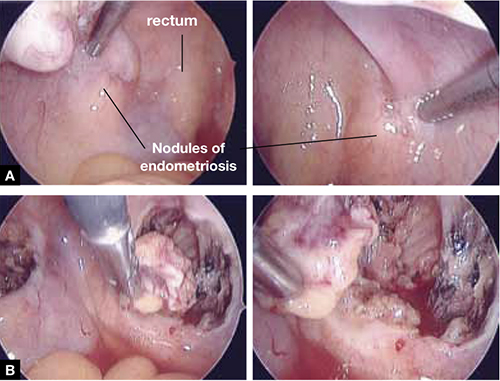

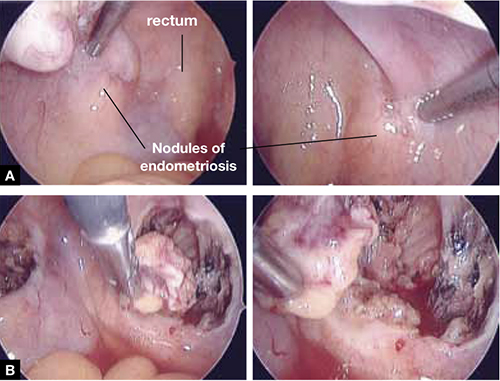

FIGURE 5 illustrates a case in which CO2 laser ablation of endometriosis that had been causing deep dyspareunia did not alleviate symptoms. Because those symptoms persisted, the patient was referred to our center, where a second laparoscopy revealed deep nodules of endometriosis, 1 to 2 cm in diameter, extending from the right and the left uterosacral ligaments deep into the perirectal space, bilaterally.

As the bottom panel of FIGURE 5 shows, excised nodules were deep and large; neither laser nor electrosurgery would have been able to ablate or devitalize the deep endometriosis at the base of these 2-cm nodules.

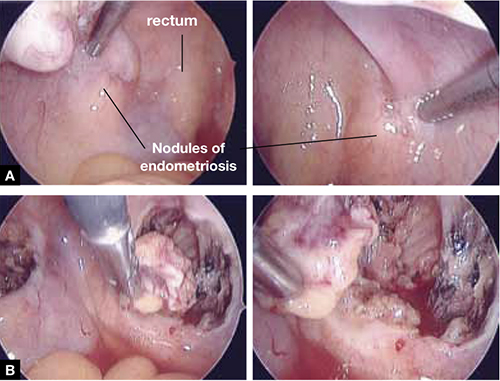

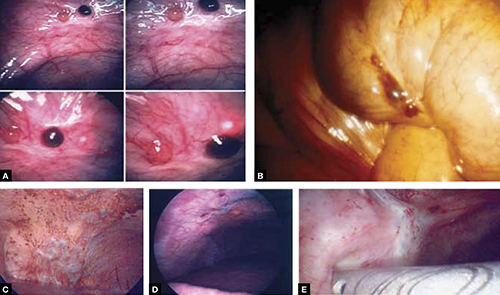

FIGURE 5 Deep nodules present a surgical challenge

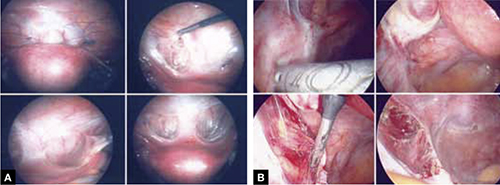

These nodules of endometriosis on the right and left uterosacral ligaments (panel A) did not respond to CO2 laser ablation. Upon progressive resection, the implants were found to be deep, extending into the perirectal space (panel B). (See also VIDEO 3, resection of endometriosis from the left uterosacal ligament, close to the ureter.) FIGURE 6, illustrates endometriosis overlying the bladder and left ureter (see also VIDEO 4). Ablation of endometriosis in these areas may be inadequate if it is not deep enough, and dangerous if it goes too deep. As FIGURE 6 shows, excision assures the surgeon that the entire lesion has been removed and that underlying vital structures have been safeguarded.

FIGURE 6 Urinary tract involvement

Endometriosis overlying the bladder is grasped, retracted, and resected (panel A). Endometriosis compresses the left ureter (panel B). The peritoneum above the lesion is entered, the ureter is displaced laterally, and the lesion is safely resected.

What we do, and recommend

When endometriosis is superficial and does not overlie vital organs, such as the bladder, ureter, and bowel, ablation and resection may be equally safe and effective. When endometriosis is deep and overlying vital organs, however, complete resection—with careful dissection of the lesion off underlying structures—offers a more complete and a safer surgical approach.

CASE continued

Now that S. D. has been treated surgically by complete excision of endometriosis, adhesions, and endometriomas, you must consider a management plan that will reduce the risks 1) of recurrence of symptoms and disease and 2) that further surgery will be necessary in the future—a risk that, in her case, exceeds 50% because of her young age, nulliparity, and the severity of her disease.20,21 Indeed, you are aware that, had preventive measures been implemented after her initial surgery 2 years earlier, it is unlikely that S. D. would have developed the second endometrioma and most likely that she would not have needed the second surgery.

Prevention of recurrence is necessary—and doable

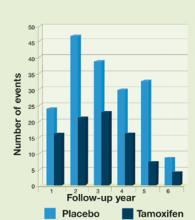

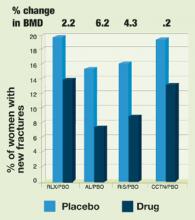

The importance of implementing preventive measures to reduce the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms has been suggested by several studies. It was underscored recently in a prospective, randomized study conducted by Serracchioli and colleagues,22 in which 239 women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriomas were randomly assigned to expectant management (control group), a cyclic oral contraceptive (OC), or a continuous oral contraceptives for 24 months, and evaluated every 6 months.

At the end of the study, recurrence of symptoms occurred in 30% of controls; 15% of subjects taking a cyclic OC; and 7.5% of the subjects taking a continuous OC. The recurrence rate of endometrioma in this study was reduced by 50% (cyclic OC) and 75% (continuous OC).22

Similar results were reported in a case-controlled study by Vercellini and co-workers,23 who found that the risk of recurrence of endometrioma was reduced by 60% when postoperative OCs were used long-term and by 30% when used for a duration of less than 12 months.

These studies suggest that, by suppressing ovulation and inducing a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea, the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms can be significantly reduced.

The importance of amenorrhea in reducing the postoperative recurrence of endometriosis and symptoms has been underscored by two important studies that evaluated the role of postoperative endometrial ablation or postoperative insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena), neither of which suppresses ovulation but both of which induce a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea.24,25

In a prospective randomized study by Bulletti and co-workers,24 28 patients who had symptomatic endometriosis underwent laparoscopic conservative surgery. Endometrial ablation was performed in 14 of the 28. Two years later, all patients underwent second-look laparoscopy; recurrence of endometriosis was found in 9 of the 14 non-ablation patients but in none in the ablation group. Resolution or significant improvement of symptoms were reported in 13 of 14 women in the ablation group but only in 3 of 14 in the non-ablation group—supporting the premise that amenorrhea or hypomenorrhea by itself, without suppressing ovulation, significantly reduces the risk that endometriosis will recur.

Similar beneficial results from hypomenorrhea/amenorrhea on the risk of recurrence of symptoms have been reported when the LNG-IUS is inserted following conservative surgery for endometriosis. In a prospective study by Vercellini and colleagues,25 40 symptomatic patients who had stage-III or stage-IV disease were randomized to either insertion of the LNG-IUS or a control group after conservative laparoscopic surgery. Recurrence of pain was significantly (P = .012) reduced in the LNG-IUS group (45%), compared with the control group (10%). Control subjects were also much less satisfied with their treatment than those who were treated with the LNG-IUS.

The importance of inducing a state of amenorrhea to reduce the risk of disease recurrence was further underscored by a recent study. Shakiba and colleagues26 reported on the recurrence of endometriosis that required further surgery as long as 7 years after the subjects had been surgically treated for symptomatic endometriosis. The need for subsequent surgery was 8% after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; 12% after hysterectomy alone; and 60% after conservative laparoscopy with preservation of both uterus and ovaries.

Taken together, these data show that, unless the patient is rendered amenorrheic or hypomenorrheic, her risk of recurrence exceeds 50%.

It is important, therefore, to consider conservative surgical management of endometriosis as only the beginning of a lifelong management plan. That plan begins with complete resection of all visible endometriosis and adhesions, resection of endometriomas, and restoration of normal anatomy as much as possible.

When endometriosis cannot be completely resected—as when it involves small bowel or the diaphragm, or is diffusely on the large bowel—we recommend medical suppressive therapy. Our preference is depot leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot), always with add-back therapy to minimize side effects, which include vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, and bone loss,27 until the patient is significantly asymptomatic, which may take 6 to 9 months.

CASE Concluded, with long-term intervention

You counsel S. D. to remain on a low-dose hormonal OC continuously, until such time that she wants to conceive. If a patient does not want to conceive for at least 5 years, the LNG-IUS may be inserted at surgery to induce hypomenorrhea and reduce the risk of recurrence for the next 5 years.

When hormonal contraceptives are inadequate to control symptoms, adding the aromatase enzyme inhibitor letrozole (Femara), 2.5 mg daily for 6 to 9 months, usually alleviates symptoms with minimal side effects, as long as the patient keeps taking a hormonal contraceptive. Using letrozole without hormonal contraception has not been studied; doing so may lead to formation of ovarian cysts, and is therefore not recommended for managing symptomatic endometriosis.

If the patient wants to become pregnant, encourage her to actively undertake fertility treatment as soon as possible after surgery, thereby minimizing the risk of recurrence of symptoms and disease. The best option may be to employ assisted reproductive technology, but patients cannot always afford it; when that is the case, consider controlled ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Bulun S E. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):268-279.

2. Gao X, Outley J, Botteman M, Spalding J, Simon JA, Pashos CL. Economic burden of endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(6):1561-1572.

3. Laufer MR, Goitein L, Bush M, Cramer DW, Emans SJ. Prevalence of endometriosis in adolescent girls with chronic pelvic pain not responding conventional therapy. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 1997;10(4):199-202.

4. Gruppo Italiano per lo studio dell’endometriosi. Prevalence and anatomic distribution of endometriosis in women with selected gynaecological conditions: results from a multicenter Italian study. Hum Reprod. 1994;9(6):1158-1162.

5. Redwine DB. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil Steril. 1999;72(2):319-315.

6. Muzii L, Marana R, Caruana P, Catalano GF, Mancuso S. Laparoscopic findings after transvaginal ultrasound-guided aspiration of ovarian endometriomas. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(11):2902-2903

7. Beretta P, Franchi M, Ghezzi F, Busacca M, Zupi E, Bolis P. Randomized clinical trial of two laparoscopic treatment of endometriomas: cystectomy versus drainage and coagulation. Fertil Steril. 1998;70(6):1176-1180

8. Alborzi S, Momtahan M, Paranezhad ME, Dehbashi S, Zolghadri J, Alborzi S. A prospective randomized study comparing laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy versus fenestration and coagulation in patients with endometriomas. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(6):1633-1637

9. Hart RJ, Hickey M, Maouris P, Buckett W, Garry R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomas. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(3):CD004992.-

10. Chang HJ, Sang HH, Jung RL, et al. Impact of laparoscopic cystectomy on ovarian reserve: serial changes of serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Fertil Steril. 2010;94(1):343-349.

11. Muzii L. Bianchi A Crocè C, Manci N, Panici PB. Laparoscopic excision of ovarian cysts: is the stripping technique a tissue sparing procedure? Fertil Steril. 2002;77(3):609-614.

12. Hachisuga T, Kawarabyashi T. Histopathological analysis of laparoscopically treated ovarian endometriotic cysts with special reference to loss of follicles. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(2):432-435.

13. Busacca M, Riparini J Somigliana E, et al. Postsurgical ovarian failure after laparoscopic excision of bilateral endometriomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195(2):421-425.

14. Nawroth F, Rahimi G, Nawroth C, Foth D, Ludwig M, Schmidt T. Is there an association between septate uterus and endometriosis? Hum Reprod. 2006;21(2):542-546.

15. Matalliotakis IM, Goumenou AG, Matalliotakis M, Arici A. Uterine anomalies in women with endometriosis. J Endometriosis. 2010;2(4):213-217.

16. Li CZ, Liu B, Wen ZQ, Sun Q. The impact of electrocoagulation on ovarian reserve after laparoscopic excision of ovarian cyst: a prospective clinical study of 191 patients. Fertil Steril. 2009;92(4):1428-1435.

17. Luciano DE, Roy G, Luciano AA. Adhesion reformation after laparoscopic adhesiolysis: where what type, and in whom are they most likely to recur. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):44-48.

18. Colin CB, Luciano AA, Martin D, et al. Adept (icodextrin 4% solution) reduces adhesions after laparoscopic surgery for adhesiolysis: a double-blind, randomized, controlled study. Fertil Steril. 2007;88(5):1413-1426.

19. Wright J, Lotfallah H, Jones K, Lovell D. A randomized study of excision vs ablation for mild endometriosis. Fertil Steril. 2004;83(6):1830-1836.

20. Cheong Y, Tay P, Luk F, Gan HC, Li TC, Cooke I. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis: How often do we need to re-operate? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2008;28(1):82-85.

21. Liu X, Yuan L, Shen F, Zhu Z, Jiang H, Guo SW. Patterns of and risk factors for recurrence in women with ovarian endometriomas. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109(6):1411-1120.

22. Seracchioli R, Mabrouk M, Frasca C, et al. Long-term cyclic and continuous oral contraceptive therapy and endometriomas recurrence: a randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2010;93(1):52-56.

23. Vercellini P, Somigliana E, Daguati R, Vigano P, Meroni F, Crosignani PG. Postoperative oral contraceptive exposure and risk of endometrioma recurrence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(5):504.e1-5.

24. Bulletti C, DeZiegler D, Stefanetti M, Cicinelli E, Pelosi E, Flamigni C. Endometriosis: absence of recurrence in patients after endometrial ablation. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(12):2676-2679.

25. Vercellini P, Frontino G, De Giorgi O, Aimi G, Zaina B, Crosignani PG. Comparison of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device versus expectant management after conservative surgery for symptomatic endometriosis: a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(2):305-309.

26. Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J, Falcone T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(6):1285-1292.

27. Surrey ES, Hornstein MD. Prolonged GnRH agonist and add-back therapy for symptomatic endometriosis: a long-term follow-up Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99(5 Pt 1):709-719.

- Resection of an endometrioma in severe disease, using a “stripping” technique

- Ovarian cystectomy

- Resection of endometriosis from the left ligament

- Resection of endometriosis on the bladder

These videos were provided by Anthony Luciano, MD.

Endometriosis affects 7% to 10% of women in the United States, mostly during reproductive years.1 The estimated annual cost for managing the approximately 10 million affected women? More than $17 billion.2 The added cost of this chronic disease, with recurrences of pain and infertility, comes in the form of serious life disruption, emotional suffering, marital and social dysfunction, and diminished productivity.

Although the prevalence of endometriosis is highest during the third and fourth decades of life, the disease is also common in adolescent girls. Indeed, 45% of adolescents who have chronic pelvic pain are found to have endometriosis; if their pain does not respond to an oral contraceptive (OC) or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, 70% are subsequently found at laparoscopy to have endometriosis.3

What is it?

Endometriosis is the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus, such as eutopic endometrium. The disease responds to effects of cyclic ovarian hormones, proliferating and bleeding with each menstrual cycle, which often leads to diffuse inflammation, adhesions, and growth of endometriotic nodules or cysts (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Drainage will not suffice

Surgical management of ovarian endometriomas must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.Symptoms tend to reflect affected organs:

- Because the pelvic organs are most often involved, the classic symptom triad of the disease comprises dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.

- Urinary urgency, dysuria, dyschezia, and tenesmus are frequent complaints when the bladder or rectosigmoid is involved.

- When distant organs are affected, such as the upper abdomen, diaphragm, lungs, and bowel, the patient may complain of respiratory symptoms, hemoptysis, pneumothorax, shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, and episodic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

The hallmark of endometriosis is catamenial symptoms, which are usually cyclic and most severe around the time of menses. Clinical signs include palpable tender nodules and fibrosis on the anterior and posterior cul de sac, fixed retroverted or anteverted uterus, and adnexal cystic masses.

Because none of these symptoms or signs is specific for endometriosis, diagnosis relies on laparoscopy, which allows the surgeon to:

- visualize it in its various appearances and locations (FIGURE 2)

- confirm the diagnosis histologically with directed excisional biopsy

- treat it surgically with either excision or ablation.

In this article, we describe various surgical techniques for the management of endometriosis. Beyond resection or ablation of lesions, however, your care should also be directed to postoperative measures to prevent its recurrence and to avoid repeated surgical interventions—which, regrettably, are much too common in women who are afflicted by this enigmatic disease.

FIGURE 2 Endometriosis: A disease of varying appearance

Lesions of endometriosis can be pink, dark, clear, or white on the pelvic sidewall (A), bowel (B), and diaphragm (C); under the rib cage (D); and on the ureter (E) (left ureter shown here).

CASE Severe disease in a young woman

S. D. is a 22-year-old unmarried nulligravida who came to the emergency service complaining of acute onset of severe low abdominal pain, which developed while she was running. She was afebrile and in obvious distress, with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness and guarding, especially on the left side.

Ultrasonography revealed a 7-cm adnexal cystic mass suggestive of endometrioma (FIGURE 3).

Two years before this episode, S. D. underwent laparoscopic resection of a 5-cm endometrioma on the right ovary. Subsequently, she was treated with a cyclic OC, which she discontinued after 1 year because she was not sexually active.

The family history is positive for endometriosis in her mother, who had undergone multiple laparoscopic investigations and, eventually, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at 40 years of age.

S. D. was treated on the emergency service with analgesics and referred to you for surgical management.

S. D. has severe disease that requires aggressive surgical resection and a lifelong management plan. That plan includes liberal use of medical therapy to prevent recurrence of symptoms and avoid repeated surgical procedures—including the total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy that her mother underwent.

What is the best immediate treatment plan? Should you:

- drain the cyst?

- drain it and coagulate or ablate its wall?

- resect the wall of the cyst?

- perform salpingo-oophorectomy?

You also ask yourself: What is the risk of recurrence of endometrioma and its symptoms after each of those treatments? And how can I reduce those risks?

FIGURE 3 Endometrioma

Endometrioma on ultrasonography (A), with its characteristic homogeneous, echogenic appearance and “ground glass” pattern, and through the laparoscope (B). These images are from the patient whose case is described in the text.

Focal point: Ovary

The ovary is the most common organ affected by endometriosis. The presence of ovarian endometriomas, in 17% to 44% of patients who have this disease,4 is often associated with an advanced stage of disease.

In a population of 1,785 patients who were surgically treated for ovarian endometriosis, Redwine reported that only 1% had exclusively ovarian involvement; 99% also had diffuse pelvic disease,5 suggesting that ovarian endometrioma is a marker of extensive disease, which often requires a gynecologic surgeon who has advanced skills and experience in the surgical management of severe endometriosis.

Simple drainage is inadequate

Surgical management of ovarian endometrioma must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.6 The currently accepted surgical management of endometrioma involves either 1) coagulation and ablation of the wall of the cyst with electrosurgery or laser or 2) removal of the cyst wall from the ovary with blunt and sharp dissection.

Several studies have compared these two techniques, but only two7,8 were prospectively randomized.

Study #1. Beretta and co-workers7 studied 64 patients who had ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm and randomized them to cystectomy by complete stripping of the cyst wall or to drainage of fluid followed by electrocoagulation to ablate the endometriosis lesions within the cyst wall. The two groups were followed for 2 years to assess the recurrence of symptoms and the pregnancy rate in the patients who were infertile.

Recurrence of symptoms and the need for medical or surgical intervention occurred with less frequency and much later in the resection group than in the ablation group: 19 months, compared to 9.5 months, postoperatively. The cumulative pregnancy rate 24 months postoperatively was also much higher in the resection group (66.7%) than in the ablative group (23.5%).

Study #2. In a later study,8 Alborzi and colleagues randomized 100 patients who had endometrioma to cystectomy or to drainage and coagulation of the cyst wall. The mean recurrence rate, 2 years postoperatively, was much lower in the excision group (15.8%) than in the ablative group (56.7%). The cumulative pregnancy rate at 12 months was higher in the excision group (54.9%, compared to 23.3%). Furthermore, the reoperation rate at 24 months was much lower in the excision group (5.8%) than in the ablative group (22.9%).

These favorable results for cystectomy over ablation were validated by a Cochrane Review, which concluded that excision of endometriomas is the preferred approach because it provides 1) a more favorable outcome than drainage and ablation, 2) lower rates of recurrence of endometriomas and symptoms, and 3) a much higher spontaneous pregnancy rate in infertile women.9

Although resection of the cyst wall is technically more challenging and takes longer to perform than drainage and ablation, we exclusively perform resection rather than ablation of endometriomas because we believe that more lasting therapeutic effects and reduced recurrence of symptoms and disease justify the extra effort and a longer procedure.

Drawback of cystectomy

A potential risk of cystectomy is that it can diminish ovarian reserve and, in rare cases, induce premature menopause, which can be devastating for women whose main purpose for having surgery is to restore or improve their fertility.

The impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve was prospectively studied by Chang and co-workers,10 who measured preoperative and postoperative levels of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) in 13 women who had endometrioma, 6 who had mature teratoma, and 1 who had mucinous cystadenoma. One week postoperatively, the AMH level decreased significantly overall in all groups. At 4 and 12 weeks postoperatively, however, the AMH level returned to preoperative levels among subjects in the non-endometrioma group but not among subjects who had endometrioma; rather, their level remained statistically lower than the preoperative level during the entire 3 months of follow-up.

Stripping the wall of an endometrioma cyst is more difficult than it is for other benign cysts, such as cystic teratoma or cystadenoma, in which there usually is a well-defined dissection plane between the wall of the cyst and surrounding stromal tissue—allowing for easy and clean separation of the wall. The cyst wall of an endometrioma, on the other hand, is intimately attached to underlying ovarian stroma; lack of a clear cleavage plane between cyst and ovarian stroma often results in unintentional removal of layers of ovarian cortex with underlying follicles, which, in turn, may lead to a reduction in ovarian reserve.

Histologic analyses of resected endometrioma cyst walls have reported follicle-containing ovarian tissue attached to the stripped cyst wall in 54% of cases.11,12 That observation explains why, and how, ovarian reserve can be compromised after resection of endometrioma.

Further risk: Ovarian failure

In rare cases, excision of endometriomas results in complete ovarian failure, described by Busacca and colleagues, who reported three cases of ovarian failure (2.4%) after resection of bilateral endometriomas in 126 patients.13 They attributed ovarian failure to excessive cauterization that compromised vascularization, as well as to excessive removal of ovarian tissue.

It is important, therefore, to strip the thinnest layer of the cyst capsule and to reduce the amount of electrocoagulation of ovarian stroma as much as possible to safeguard functional ovarian tissue.

CASE continued

S. D. was scheduled for laparoscopy to remove the endometrioma and other concurrent pelvic and peritoneal pathology, such as endometriosis and pelvic adhesions. You also scheduled her for hysteroscopy to evaluate the endometrial cavity for potential pathology, such as endometrial polyps and uterine septum, which appear to be more common in women who have endometriosis.

Nawroth and co-workers14 found a much higher incidence of endometriosis in patients who had a septate uterus. Metalliotakis and co-workers15 found congenital uterine malformations to be more common in patients who had endometriosis, compared with controls; uterine septum was, by far, the most common anomaly.

CASE continued

Hysteroscopy revealed a small and broad septum, which was resected sharply with hysteroscopic scissors (FIGURE 4). Laparoscopy revealed a 7-cm endometrioma on the left ovary, with adhesions to the posterior broad ligament and pelvic sidewall. S. D. also had deep implants of endometriosis on the left pelvic sidewall, the posterior cul de sac, the right pelvic sidewall, and the right ovary, which was cohesively adherent to the ovarian fossa.

As you expected, S. D. has stage-IV disease, according to the revised American Fertility Society Classification.

Following adhesiolysis, the endometrioma was resected (see VIDEO 1). Because of the large ovarian defect, the edges of the ovary were approximated with imbricating running 3-0 Vicryl suture. Deep endometriosis was also resected. Superficial endometriosis was peeled off or coagulated using bipolar forceps.

Note: Alternatively, and with comparable results, resection may be performed with a laser or other energy source. We prefer resection, rather than ablation, of deep endometriosis, but no data exists to support one technique over the other.

FIGURE 4 Septate uterus with deep cornua

Through the hysteroscope, a shallow septum is visible at the fundus of the uterus, dividing the upper endometrial cavity into two chambers (A), with deep cornua on the left (B) and right (C). Normal fundal anatomy is restored by septolysis along the avascular plane (D).

Technique: How we resect endometrioma

In removing endometrioma (see VIDEO 2), it is important to grasp the thinnest part of the cyst wall and progressively strip it, to avoid removing excess ovarian tissue and to reduce the risk of compromising ovarian reserve.

After draining the endometrioma of its chocolate-colored fluid, we irrigate and drain the cyst several times with warm lactated Ringers’ solution to promote separation of the cyst wall from underlying stroma and better identify the dissection plane. The cyst wall is inspected by introducing the laparoscope into the cyst to examine its surface, which is often laden with implants of deep and superficial endometriosis.

If we cannot easily identify the plane of dissection along the edges, we may evert the cyst and make an incision at its base to create a wedge between the wall of the cyst and underlying stroma. The edge of the incised wall is then grasped and retracted to create a space between the wall and the underlying stroma, from which it is progressively stripped from the ovary.

Traction and counter-traction are the hallmarks of dissection here; sometimes, we use laparoscopic scissors to sharply resect the ovarian stromal attachments that adhere cohesively to the cyst wall. This technique is continued until the entire cyst wall is removed. When follicle-containing ovarian tissue remains attached to the cyst wall, we introduce the closed tips of the Dolphin forceps between the cyst wall and adjacent follicle-containing stroma, spread the tips apart, and recover the true plane of dissection between the thin wall of the cyst and stroma.

After the wall of the cyst is removed, the ovarian crater invariably bleeds because blood vessels supplying the wall have been separated and opened. Utilizing warm lactated Ringers’ solution, we copiously irrigate the bleeding ovarian stroma to identify each bleeding vessel and, by placing the tips of the micro-bipolar forceps on either side of the bleeder, individually coagulate each vessel, thus inflicting minimal thermal damage to the surrounding stroma.

Pearl. Avoid using Kleppinger forceps to indiscriminately coagulate the bloody stroma in the crater created after the cystectomy, because doing so can result in excessive destruction of ovarian tissue or inadvertent coagulation of hylar vessels that would interrupt the blood supply to the ovary, compromising its function.16

Suturing. Some surgeons find that fenestration, drainage, and coagulation of the cyst wall is acceptable, but we have concerns not only about incomplete ablation of the endometriosis on the cyst wall, which may be responsible for the higher recurrence rate of disease, but also about the risk of thermal injury to underlying follicles, which may compromise ovarian reserve.16

Hemostasis. Once complete hemostasis has been achieved, the decision to approximate (or not) the edges, preferably with fine absorbable suture, is based on how large the defect is and whether or not the edges of the crater spontaneously come together. For large craters, we usually close the ovary with a 3-0 or 4-0 Vicryl continuous suture, imbricating the edges to expose as little suture material as possible to reduce postoperative formation of adhesions, which is common after ovarian surgery.17

Last, we ensure that hemostasis is present. Often we apply an anti-adhesion solution, such as icodextrin 4% (Adept). This agent has been shown to reduce postoperative adhesion formation, especially after laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis.18

A high level of skill is needed

Ovarian endometriomas signal advanced disease; advanced surgical skills are required to treat them adequately. Simple drainage is of little therapeutic value and should seldom be considered a treatment option. Although drainage plus ablation of the cyst wall ameliorates symptoms, excision of endometriomas should be considered preferable because it provides a more favorable outcome, a lower risk of recurrence of endometriomas and symptoms, and a higher rate of spontaneous pregnancy in previously infertile women.7-9

To recap, we advise the surgeon to:

- Manage ovarian endometriomas with resection of the entire cyst wall, grasping and stripping the thinnest layer of the cyst wall without removing underlying functional ovarian stroma.

- Avoid excessive cauterization of the underlying ovarian stroma by utilizing micro-bipolar forceps and applying energy only around bleeding vessels.

- Close stromal defects, when the crater is large and its edges do not spontaneously come together, by approximating the edges with an imbricating resorbable suture.

CASE continued

As in most cases of advanced endometriosis, S. D. also had diffuse implants of deep and superficial endometriosis on the peritoneum of the pelvic sidewalls and on the anterior and posterior cul de sac.

Should you ablate or resect these lesions? Are there advantages to either approach?

Ablation of endometriosis implants may involve either electrocoagulation of the lesion with bipolar energy or laser vaporization/coagulation, which destroys or devitalizes active endometriosis but does not actually remove the lesion. Ablation destroys the lesion without getting a specimen for histologic diagnosis.

Resection of endometriosis implants involves complete removal of the lesion from its epithelial surface to the depth of its base. Resection can be performed with scissors, laser, or monopolar electrosurgery. Resection removes the lesion in its entirety, yielding a histologic diagnosis and allowing you to determine whether, indeed, the entire specimen has been removed.

The question of what is more effective—ablating or resecting endometriosis implants?—was addressed in a prospective study in which 141 patients with endometriosis-related pain were randomized at laparoscopic surgery to either excision or ablation/coagulation of endometriosis lesions.19 Six months postoperatively, the pain score decreased by, on average, 11.2 points in the excision group and 8.7 points in the coagulation/ablative group.

Because the difference in those average pain scores was not statistically significant, however, investigators concluded that the techniques are comparable, with similar efficacy. That interpretation has been criticized because the study was underpowered and included only patients who had mild endometriosis—leaving open the possibility that deep endometriosis may not be adequately treated by electrocoagulation or ablation.

In contrast to superficial endometriosis, which may respond similarly to ablation or resection, deep endometriosis is difficult to ablate either with electrosurgery or a laser because the energy cannot reach deeper layers and active disease is therefore likely to be left behind. Moreover, when endometriosis overlies vital structures, such as the ureter or bowel, ablation of the lesion may cause thermal damage to the underlying organ, and such damage may not manifest until several days later, when the patient experiences, say, urinary leakage in the peritoneum or symptoms of bowel perforation.

FIGURE 5 illustrates a case in which CO2 laser ablation of endometriosis that had been causing deep dyspareunia did not alleviate symptoms. Because those symptoms persisted, the patient was referred to our center, where a second laparoscopy revealed deep nodules of endometriosis, 1 to 2 cm in diameter, extending from the right and the left uterosacral ligaments deep into the perirectal space, bilaterally.

As the bottom panel of FIGURE 5 shows, excised nodules were deep and large; neither laser nor electrosurgery would have been able to ablate or devitalize the deep endometriosis at the base of these 2-cm nodules.

FIGURE 5 Deep nodules present a surgical challenge

These nodules of endometriosis on the right and left uterosacral ligaments (panel A) did not respond to CO2 laser ablation. Upon progressive resection, the implants were found to be deep, extending into the perirectal space (panel B). (See also VIDEO 3, resection of endometriosis from the left uterosacal ligament, close to the ureter.) FIGURE 6, illustrates endometriosis overlying the bladder and left ureter (see also VIDEO 4). Ablation of endometriosis in these areas may be inadequate if it is not deep enough, and dangerous if it goes too deep. As FIGURE 6 shows, excision assures the surgeon that the entire lesion has been removed and that underlying vital structures have been safeguarded.

FIGURE 6 Urinary tract involvement

Endometriosis overlying the bladder is grasped, retracted, and resected (panel A). Endometriosis compresses the left ureter (panel B). The peritoneum above the lesion is entered, the ureter is displaced laterally, and the lesion is safely resected.

What we do, and recommend

When endometriosis is superficial and does not overlie vital organs, such as the bladder, ureter, and bowel, ablation and resection may be equally safe and effective. When endometriosis is deep and overlying vital organs, however, complete resection—with careful dissection of the lesion off underlying structures—offers a more complete and a safer surgical approach.

CASE continued

Now that S. D. has been treated surgically by complete excision of endometriosis, adhesions, and endometriomas, you must consider a management plan that will reduce the risks 1) of recurrence of symptoms and disease and 2) that further surgery will be necessary in the future—a risk that, in her case, exceeds 50% because of her young age, nulliparity, and the severity of her disease.20,21 Indeed, you are aware that, had preventive measures been implemented after her initial surgery 2 years earlier, it is unlikely that S. D. would have developed the second endometrioma and most likely that she would not have needed the second surgery.

Prevention of recurrence is necessary—and doable

The importance of implementing preventive measures to reduce the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms has been suggested by several studies. It was underscored recently in a prospective, randomized study conducted by Serracchioli and colleagues,22 in which 239 women who had undergone laparoscopic resection of endometriomas were randomly assigned to expectant management (control group), a cyclic oral contraceptive (OC), or a continuous oral contraceptives for 24 months, and evaluated every 6 months.

At the end of the study, recurrence of symptoms occurred in 30% of controls; 15% of subjects taking a cyclic OC; and 7.5% of the subjects taking a continuous OC. The recurrence rate of endometrioma in this study was reduced by 50% (cyclic OC) and 75% (continuous OC).22

Similar results were reported in a case-controlled study by Vercellini and co-workers,23 who found that the risk of recurrence of endometrioma was reduced by 60% when postoperative OCs were used long-term and by 30% when used for a duration of less than 12 months.

These studies suggest that, by suppressing ovulation and inducing a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea, the risk of recurrence of endometriosis and its symptoms can be significantly reduced.

The importance of amenorrhea in reducing the postoperative recurrence of endometriosis and symptoms has been underscored by two important studies that evaluated the role of postoperative endometrial ablation or postoperative insertion of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Mirena), neither of which suppresses ovulation but both of which induce a state of hypomenorrhea or amenorrhea.24,25

In a prospective randomized study by Bulletti and co-workers,24 28 patients who had symptomatic endometriosis underwent laparoscopic conservative surgery. Endometrial ablation was performed in 14 of the 28. Two years later, all patients underwent second-look laparoscopy; recurrence of endometriosis was found in 9 of the 14 non-ablation patients but in none in the ablation group. Resolution or significant improvement of symptoms were reported in 13 of 14 women in the ablation group but only in 3 of 14 in the non-ablation group—supporting the premise that amenorrhea or hypomenorrhea by itself, without suppressing ovulation, significantly reduces the risk that endometriosis will recur.

Similar beneficial results from hypomenorrhea/amenorrhea on the risk of recurrence of symptoms have been reported when the LNG-IUS is inserted following conservative surgery for endometriosis. In a prospective study by Vercellini and colleagues,25 40 symptomatic patients who had stage-III or stage-IV disease were randomized to either insertion of the LNG-IUS or a control group after conservative laparoscopic surgery. Recurrence of pain was significantly (P = .012) reduced in the LNG-IUS group (45%), compared with the control group (10%). Control subjects were also much less satisfied with their treatment than those who were treated with the LNG-IUS.

The importance of inducing a state of amenorrhea to reduce the risk of disease recurrence was further underscored by a recent study. Shakiba and colleagues26 reported on the recurrence of endometriosis that required further surgery as long as 7 years after the subjects had been surgically treated for symptomatic endometriosis. The need for subsequent surgery was 8% after hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy; 12% after hysterectomy alone; and 60% after conservative laparoscopy with preservation of both uterus and ovaries.

Taken together, these data show that, unless the patient is rendered amenorrheic or hypomenorrheic, her risk of recurrence exceeds 50%.

It is important, therefore, to consider conservative surgical management of endometriosis as only the beginning of a lifelong management plan. That plan begins with complete resection of all visible endometriosis and adhesions, resection of endometriomas, and restoration of normal anatomy as much as possible.

When endometriosis cannot be completely resected—as when it involves small bowel or the diaphragm, or is diffusely on the large bowel—we recommend medical suppressive therapy. Our preference is depot leuprolide acetate (Lupron Depot), always with add-back therapy to minimize side effects, which include vasomotor symptoms, vaginal dryness, and bone loss,27 until the patient is significantly asymptomatic, which may take 6 to 9 months.

CASE Concluded, with long-term intervention

You counsel S. D. to remain on a low-dose hormonal OC continuously, until such time that she wants to conceive. If a patient does not want to conceive for at least 5 years, the LNG-IUS may be inserted at surgery to induce hypomenorrhea and reduce the risk of recurrence for the next 5 years.

When hormonal contraceptives are inadequate to control symptoms, adding the aromatase enzyme inhibitor letrozole (Femara), 2.5 mg daily for 6 to 9 months, usually alleviates symptoms with minimal side effects, as long as the patient keeps taking a hormonal contraceptive. Using letrozole without hormonal contraception has not been studied; doing so may lead to formation of ovarian cysts, and is therefore not recommended for managing symptomatic endometriosis.

If the patient wants to become pregnant, encourage her to actively undertake fertility treatment as soon as possible after surgery, thereby minimizing the risk of recurrence of symptoms and disease. The best option may be to employ assisted reproductive technology, but patients cannot always afford it; when that is the case, consider controlled ovarian stimulation and intrauterine insemination.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Resection of an endometrioma in severe disease, using a “stripping” technique

- Ovarian cystectomy

- Resection of endometriosis from the left ligament

- Resection of endometriosis on the bladder

These videos were provided by Anthony Luciano, MD.

Endometriosis affects 7% to 10% of women in the United States, mostly during reproductive years.1 The estimated annual cost for managing the approximately 10 million affected women? More than $17 billion.2 The added cost of this chronic disease, with recurrences of pain and infertility, comes in the form of serious life disruption, emotional suffering, marital and social dysfunction, and diminished productivity.

Although the prevalence of endometriosis is highest during the third and fourth decades of life, the disease is also common in adolescent girls. Indeed, 45% of adolescents who have chronic pelvic pain are found to have endometriosis; if their pain does not respond to an oral contraceptive (OC) or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, 70% are subsequently found at laparoscopy to have endometriosis.3

What is it?

Endometriosis is the presence of functional endometrial tissue outside the uterus, such as eutopic endometrium. The disease responds to effects of cyclic ovarian hormones, proliferating and bleeding with each menstrual cycle, which often leads to diffuse inflammation, adhesions, and growth of endometriotic nodules or cysts (FIGURE 1).

FIGURE 1 Drainage will not suffice

Surgical management of ovarian endometriomas must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.Symptoms tend to reflect affected organs:

- Because the pelvic organs are most often involved, the classic symptom triad of the disease comprises dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and infertility.

- Urinary urgency, dysuria, dyschezia, and tenesmus are frequent complaints when the bladder or rectosigmoid is involved.

- When distant organs are affected, such as the upper abdomen, diaphragm, lungs, and bowel, the patient may complain of respiratory symptoms, hemoptysis, pneumothorax, shoulder pain, upper abdominal pain, and episodic gastrointestinal dysfunction.

The hallmark of endometriosis is catamenial symptoms, which are usually cyclic and most severe around the time of menses. Clinical signs include palpable tender nodules and fibrosis on the anterior and posterior cul de sac, fixed retroverted or anteverted uterus, and adnexal cystic masses.

Because none of these symptoms or signs is specific for endometriosis, diagnosis relies on laparoscopy, which allows the surgeon to:

- visualize it in its various appearances and locations (FIGURE 2)

- confirm the diagnosis histologically with directed excisional biopsy

- treat it surgically with either excision or ablation.

In this article, we describe various surgical techniques for the management of endometriosis. Beyond resection or ablation of lesions, however, your care should also be directed to postoperative measures to prevent its recurrence and to avoid repeated surgical interventions—which, regrettably, are much too common in women who are afflicted by this enigmatic disease.

FIGURE 2 Endometriosis: A disease of varying appearance

Lesions of endometriosis can be pink, dark, clear, or white on the pelvic sidewall (A), bowel (B), and diaphragm (C); under the rib cage (D); and on the ureter (E) (left ureter shown here).

CASE Severe disease in a young woman

S. D. is a 22-year-old unmarried nulligravida who came to the emergency service complaining of acute onset of severe low abdominal pain, which developed while she was running. She was afebrile and in obvious distress, with diffuse lower abdominal tenderness and guarding, especially on the left side.

Ultrasonography revealed a 7-cm adnexal cystic mass suggestive of endometrioma (FIGURE 3).

Two years before this episode, S. D. underwent laparoscopic resection of a 5-cm endometrioma on the right ovary. Subsequently, she was treated with a cyclic OC, which she discontinued after 1 year because she was not sexually active.

The family history is positive for endometriosis in her mother, who had undergone multiple laparoscopic investigations and, eventually, total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy at 40 years of age.

S. D. was treated on the emergency service with analgesics and referred to you for surgical management.

S. D. has severe disease that requires aggressive surgical resection and a lifelong management plan. That plan includes liberal use of medical therapy to prevent recurrence of symptoms and avoid repeated surgical procedures—including the total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy that her mother underwent.

What is the best immediate treatment plan? Should you:

- drain the cyst?

- drain it and coagulate or ablate its wall?

- resect the wall of the cyst?

- perform salpingo-oophorectomy?

You also ask yourself: What is the risk of recurrence of endometrioma and its symptoms after each of those treatments? And how can I reduce those risks?

FIGURE 3 Endometrioma

Endometrioma on ultrasonography (A), with its characteristic homogeneous, echogenic appearance and “ground glass” pattern, and through the laparoscope (B). These images are from the patient whose case is described in the text.

Focal point: Ovary

The ovary is the most common organ affected by endometriosis. The presence of ovarian endometriomas, in 17% to 44% of patients who have this disease,4 is often associated with an advanced stage of disease.

In a population of 1,785 patients who were surgically treated for ovarian endometriosis, Redwine reported that only 1% had exclusively ovarian involvement; 99% also had diffuse pelvic disease,5 suggesting that ovarian endometrioma is a marker of extensive disease, which often requires a gynecologic surgeon who has advanced skills and experience in the surgical management of severe endometriosis.

Simple drainage is inadequate

Surgical management of ovarian endometrioma must go beyond simple drainage, which has little therapeutic value because symptoms recur and endometriomas re-form quickly after simple drainage in almost all patients.6 The currently accepted surgical management of endometrioma involves either 1) coagulation and ablation of the wall of the cyst with electrosurgery or laser or 2) removal of the cyst wall from the ovary with blunt and sharp dissection.

Several studies have compared these two techniques, but only two7,8 were prospectively randomized.

Study #1. Beretta and co-workers7 studied 64 patients who had ovarian endometriomas larger than 3 cm and randomized them to cystectomy by complete stripping of the cyst wall or to drainage of fluid followed by electrocoagulation to ablate the endometriosis lesions within the cyst wall. The two groups were followed for 2 years to assess the recurrence of symptoms and the pregnancy rate in the patients who were infertile.

Recurrence of symptoms and the need for medical or surgical intervention occurred with less frequency and much later in the resection group than in the ablation group: 19 months, compared to 9.5 months, postoperatively. The cumulative pregnancy rate 24 months postoperatively was also much higher in the resection group (66.7%) than in the ablative group (23.5%).

Study #2. In a later study,8 Alborzi and colleagues randomized 100 patients who had endometrioma to cystectomy or to drainage and coagulation of the cyst wall. The mean recurrence rate, 2 years postoperatively, was much lower in the excision group (15.8%) than in the ablative group (56.7%). The cumulative pregnancy rate at 12 months was higher in the excision group (54.9%, compared to 23.3%). Furthermore, the reoperation rate at 24 months was much lower in the excision group (5.8%) than in the ablative group (22.9%).

These favorable results for cystectomy over ablation were validated by a Cochrane Review, which concluded that excision of endometriomas is the preferred approach because it provides 1) a more favorable outcome than drainage and ablation, 2) lower rates of recurrence of endometriomas and symptoms, and 3) a much higher spontaneous pregnancy rate in infertile women.9

Although resection of the cyst wall is technically more challenging and takes longer to perform than drainage and ablation, we exclusively perform resection rather than ablation of endometriomas because we believe that more lasting therapeutic effects and reduced recurrence of symptoms and disease justify the extra effort and a longer procedure.

Drawback of cystectomy

A potential risk of cystectomy is that it can diminish ovarian reserve and, in rare cases, induce premature menopause, which can be devastating for women whose main purpose for having surgery is to restore or improve their fertility.

The impact of laparoscopic ovarian cystectomy on ovarian reserve was prospectively studied by Chang and co-workers,10 who measured preoperative and postoperative levels of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) in 13 women who had endometrioma, 6 who had mature teratoma, and 1 who had mucinous cystadenoma. One week postoperatively, the AMH level decreased significantly overall in all groups. At 4 and 12 weeks postoperatively, however, the AMH level returned to preoperative levels among subjects in the non-endometrioma group but not among subjects who had endometrioma; rather, their level remained statistically lower than the preoperative level during the entire 3 months of follow-up.

Stripping the wall of an endometrioma cyst is more difficult than it is for other benign cysts, such as cystic teratoma or cystadenoma, in which there usually is a well-defined dissection plane between the wall of the cyst and surrounding stromal tissue—allowing for easy and clean separation of the wall. The cyst wall of an endometrioma, on the other hand, is intimately attached to underlying ovarian stroma; lack of a clear cleavage plane between cyst and ovarian stroma often results in unintentional removal of layers of ovarian cortex with underlying follicles, which, in turn, may lead to a reduction in ovarian reserve.

Histologic analyses of resected endometrioma cyst walls have reported follicle-containing ovarian tissue attached to the stripped cyst wall in 54% of cases.11,12 That observation explains why, and how, ovarian reserve can be compromised after resection of endometrioma.

Further risk: Ovarian failure

In rare cases, excision of endometriomas results in complete ovarian failure, described by Busacca and colleagues, who reported three cases of ovarian failure (2.4%) after resection of bilateral endometriomas in 126 patients.13 They attributed ovarian failure to excessive cauterization that compromised vascularization, as well as to excessive removal of ovarian tissue.

It is important, therefore, to strip the thinnest layer of the cyst capsule and to reduce the amount of electrocoagulation of ovarian stroma as much as possible to safeguard functional ovarian tissue.

CASE continued

S. D. was scheduled for laparoscopy to remove the endometrioma and other concurrent pelvic and peritoneal pathology, such as endometriosis and pelvic adhesions. You also scheduled her for hysteroscopy to evaluate the endometrial cavity for potential pathology, such as endometrial polyps and uterine septum, which appear to be more common in women who have endometriosis.

Nawroth and co-workers14 found a much higher incidence of endometriosis in patients who had a septate uterus. Metalliotakis and co-workers15 found congenital uterine malformations to be more common in patients who had endometriosis, compared with controls; uterine septum was, by far, the most common anomaly.

CASE continued

Hysteroscopy revealed a small and broad septum, which was resected sharply with hysteroscopic scissors (FIGURE 4). Laparoscopy revealed a 7-cm endometrioma on the left ovary, with adhesions to the posterior broad ligament and pelvic sidewall. S. D. also had deep implants of endometriosis on the left pelvic sidewall, the posterior cul de sac, the right pelvic sidewall, and the right ovary, which was cohesively adherent to the ovarian fossa.

As you expected, S. D. has stage-IV disease, according to the revised American Fertility Society Classification.

Following adhesiolysis, the endometrioma was resected (see VIDEO 1). Because of the large ovarian defect, the edges of the ovary were approximated with imbricating running 3-0 Vicryl suture. Deep endometriosis was also resected. Superficial endometriosis was peeled off or coagulated using bipolar forceps.

Note: Alternatively, and with comparable results, resection may be performed with a laser or other energy source. We prefer resection, rather than ablation, of deep endometriosis, but no data exists to support one technique over the other.

FIGURE 4 Septate uterus with deep cornua

Through the hysteroscope, a shallow septum is visible at the fundus of the uterus, dividing the upper endometrial cavity into two chambers (A), with deep cornua on the left (B) and right (C). Normal fundal anatomy is restored by septolysis along the avascular plane (D).

Technique: How we resect endometrioma

In removing endometrioma (see VIDEO 2), it is important to grasp the thinnest part of the cyst wall and progressively strip it, to avoid removing excess ovarian tissue and to reduce the risk of compromising ovarian reserve.

After draining the endometrioma of its chocolate-colored fluid, we irrigate and drain the cyst several times with warm lactated Ringers’ solution to promote separation of the cyst wall from underlying stroma and better identify the dissection plane. The cyst wall is inspected by introducing the laparoscope into the cyst to examine its surface, which is often laden with implants of deep and superficial endometriosis.

If we cannot easily identify the plane of dissection along the edges, we may evert the cyst and make an incision at its base to create a wedge between the wall of the cyst and underlying stroma. The edge of the incised wall is then grasped and retracted to create a space between the wall and the underlying stroma, from which it is progressively stripped from the ovary.

Traction and counter-traction are the hallmarks of dissection here; sometimes, we use laparoscopic scissors to sharply resect the ovarian stromal attachments that adhere cohesively to the cyst wall. This technique is continued until the entire cyst wall is removed. When follicle-containing ovarian tissue remains attached to the cyst wall, we introduce the closed tips of the Dolphin forceps between the cyst wall and adjacent follicle-containing stroma, spread the tips apart, and recover the true plane of dissection between the thin wall of the cyst and stroma.

After the wall of the cyst is removed, the ovarian crater invariably bleeds because blood vessels supplying the wall have been separated and opened. Utilizing warm lactated Ringers’ solution, we copiously irrigate the bleeding ovarian stroma to identify each bleeding vessel and, by placing the tips of the micro-bipolar forceps on either side of the bleeder, individually coagulate each vessel, thus inflicting minimal thermal damage to the surrounding stroma.

Pearl. Avoid using Kleppinger forceps to indiscriminately coagulate the bloody stroma in the crater created after the cystectomy, because doing so can result in excessive destruction of ovarian tissue or inadvertent coagulation of hylar vessels that would interrupt the blood supply to the ovary, compromising its function.16