User login

Describing Variability of Inpatient Consultation Practices: Physician, Patient, and Admission Factors

Inpatient consultation is an extremely common practice with the potential to improve patient outcomes significantly.1-3 However, variability in consultation practices may be risky for patients. In addition to underuse when the benefit is clear, the overuse of consultation may lead to additional testing and therapies, increased length of stay (LOS) and costs, conflicting recommendations, and opportunities for communication breakdown.

Consultation use is often at the discretion of individual providers. While this decision is frequently driven by patient needs, significant variation in consultation practices not fully explained by patient factors exists.1 Prior work has described hospital-level variation1 and that primary care physicians use more consultation than hospitalists.4 However, other factors affecting consultation remain unknown. We sought to explore physician-, patient-, and admission-level factors associated with consultation use on inpatient general medicine services.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project (UCHP). UCHP is a longstanding study of the care of hospitalized patients admitted to the University of Chicago general medicine services, involving both patient data collection and physician experience surveys.5 Data were obtained for enrolled UCHP patients between 2011-2016 from the Center for Research Informatics (CRI). The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

Attendings and patients consented to UCHP participation. Data collection details are described elsewhere.5,6 Data from EpicCare (EpicSystems Corp, Wisconsin) and Centricity Billing (GE Healthcare, Illinois) were obtained via CRI for all encounters of enrolled UCHP patients during the study period (N = 218,591).

Attending Attribution

We determined attending attribution for admissions as follows: the attending author of the first history and physical (H&P) was assigned. If this was unavailable, the attending author of the first progress note (PN) was assigned. For patients admitted by hospitalists on admitting shifts to nonteaching services (ie, service without residents/students), the author of the first PN was assigned if different from H&P. Where available, attribution was corroborated with call schedules.

Sample and Variables

All encounters containing inpatient admissions to the University of Chicago from May 10, 2011 (Electronic Health Record activation date), through December 31, 2016, were considered for inclusion (N = 51,171, Appendix 1). Admissions including only documentation from ancillary services were excluded (eg, encounters for hemodialysis or physical therapy). Admissions were limited to a length of stay (LOS) ≤ 5 days, corresponding to the average US inpatient LOS of 4.6 days,7 to minimize the likelihood of attending handoffs (N = 31,592). If attending attribution was not possible via the above-described methods, the admission was eliminated (N = 3,103; 10.9% of admissions with LOS ≤ 5 days). Finally, the sample was restricted to general medicine service admissions under attendings enrolled in UCHP who completed surveys. After the application of all criteria, 6,153 admissions remained for analysis.

The outcome variable was the number of consultations per admission, determined by counting the unique number of services creating clinical documentation, and subtracting one for the primary team. If the Medical/Surgical intensive care unit (ICU) was a service, then two were subtracted to account for the ICU transfer.

Attending years in practice (ie, years since medical school graduation) and gender were determined from public resources. Practice characteristics were determined from UCHP attending surveys, which address perceptions of workload and satisfaction (Appendix 2).

Patient characteristics (gender, age, Elixhauser Indices) and admission characteristics (LOS, season of admission, payor) were determined from UCHP and CRI data. The Elixhauser Index uses a well-validated system combining the presence/absence of 31 comorbidities to predict mortality and 30-day readmission.8 Elixhauser Indices were calculated using the “Creation of Elixhauser Comorbidity Index Scores 1.0” software.9 For admissions under hospitalist attendings, teaching/nonteaching team was ascertained via internal teaching service calendars.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine demographic characteristics. The difference between the lowest and highest quartile consultation use was determined via a two-sample t test. Given the multilevel nature of our count data, we used a mixed-effects Poisson model accounting for within-group variation by clustering on attending and patient (3-level random-effects model). The analysis was done using Stata 15 (StataCorp, Texas).

RESULTS

From 2011 to 2016, 14,848 patients and 88 attendings were enrolled in UCHP; 4,772 patients (32%) and 69 attendings (59.4%) had data available and were included. Mean LOS was 3.0 days (SD = 1.3). Table 1 describes the characteristics of attendings, patients, and admissions.

Seventy-six percent of admissions included at least one consultation. Consultation use varied widely, ranging from 0 to 10 per admission (mean = 1.39, median = 1; standard deviation [SD] = 1.17). The number of consultations per admission in the highest quartile of consultation frequency (mean = 3.47, median = 3) was 5.7-fold that of the lowest quartile (mean = 0.613, median = 1; P <.001).

In multivariable regression, physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics were associated with the differential use of consultation (Table 2). On teaching services, consultations called by hospitalist vs nonhospitalist generalists did not differ (P =.361). However, hospitalists on nonteaching services called 8.6% more consultations than hospitalists on teaching services (P =.02). Attending agreement with survey item “The interruption of my personal life by work is a problem” was associated with 8.2% fewer consultations per admission (P =.002).

Patients older than 75 years received 19% fewer consultations compared with patients younger than 49 years (P <.001). Compared with Medicare, Medicaid admissions had 12.2% fewer consultations (P <.001), whereas privately insured admissions had 10.7% more (P =.001). The number of consultations per admission decreased every year, with 45.3% fewer consultations in 2015 than 2011 (P <.001). Consultations increased by each 22% per day increase in LOS (P <.001).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis described several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics associated with the use of inpatient consultation. Our results strengthen prior work demonstrating that patient-level factors alone are insufficient to explain consultation variability.1

Hospitalists on nonteaching services called more consultations, which may reflect a higher workload on these services. Busy hospitalists on nonteaching teams may lack time to delve deeply into clinical problems and require more consultations, especially for work with heavy cognitive loads such as diagnosis. “Outsourcing” tasks when workload increases occurs in other cognitive activities such as teaching.10 The association between work interrupting personal life and fewer consultations may also implicate the effects of time. Attendings who are experiencing work encroaching on their personal lives may be those spending more time with patients and consulting less. This finding merits further study, especially with increasing concern about balancing time spent in meaningful patient care activities with risk of physician burnout.

This finding could also indicate that trainee participation modifies consultation use for hospitalists. Teaching service teams with more individual members may allow a greater pool of collective knowledge, decreasing the need for consultation to answer clinical questions.11 Interestingly, there was no difference in consultation use between generalists or subspecialists and hospitalists on teaching services, possibly suggesting a unique effect in hospitalists who vary clinical practice depending on team structure. These differences deserve further investigation, with implications for education and resource utilization.

We were surprised by the finding that consultations decreased each year, despite increasing patient complexity and availability of consultation services. This could be explained by a growing emphasis on shortening LOS in our institution, thus shifting consultative care to outpatient settings. Understanding these effects is critically important with growing evidence that consultation improves patient outcomes because these external pressures could lead to unintended consequences for quality or access to care.

Several findings related to patient factors additionally emerged, including age and insurance status. Although related to medical complexity, these effects persist despite adjustment, which raises the question of whether they contribute to the decision to seek consultation. Older patients received fewer consultations, which could reflect the use of more conservative practice models in the elderly,12 or ageism, which is associated with undertreatment.13 With respect to insurance status, Medicaid patients were associated with fewer consultations. This finding is consistent with previous work showing the decreased intensity of hospital services used for Medicaid patients.14Our study has limitations. Our data were from one large urban academic center that limits generalizability. Although systematic and redundant, attending attribution may have been flawed: incomplete or erroneous documentation could have led to attribution error, and we cannot rule out the possibility of service handoffs. We used a LOS ≤ 5 days to minimize this possibility, but this limits the applicability of our findings to longer admissions. Unsurprisingly, longer LOS correlated with the increased use of consultation even within our restricted sample, and future work should examine the effects of prolonged LOS. As a retrospective analysis, unmeasured confounders due to our limited adjustment will likely explain some findings, although we took steps to address this in our statistical design. Finally, we could not measure patient outcomes and, therefore, cannot determine the value of more or fewer consultations for specific patients or illnesses. Positive and negative outcomes of increased consultation are described, and understanding the impact of consultation is critical for further study.2,3

CONCLUSION

We found that the use of consultation on general medicine services varies widely between admissions, with large differences between the highest and lowest frequencies of use. This variation can be partially explained by several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics. Our work may help identify patient and attending groups at high risk for under- or overuse of consultation and guide the subsequent development of interventions to improve value in consultation. One additional consultation over the average LOS of 4.6 days adds $420 per admission or $4.8 billion to the 11.5 million annual Medicare admissions.15 Increasing research, guidelines, and education on the judicious use of inpatient consultation will be key in maximizing high-value care and improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable support and assistance of the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, the Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program, the University of Chicago Center for Quality, and the University of Chicago Center for Health and the Social Sciences (CHeSS). The authors would additionally like to thank John Cursio, PhD, for his support and guidance in statistical analysis for this project.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Preliminary results of this analysis were presented at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript. The submission is not under review by any other publication.

1. Stevens JP, Nyweide D, Maresh S, et al. Variation in inpatient consultation among older adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):992-999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3216-7.

2. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, Schwartzman J, Kirkland K. Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(5):263-267. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181b8fccb.

3. Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2011;30(3):454-463. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929.

4. Stevens JP, Nyweide DJ, Maresh S, Hatfield LA, Howell MD, Landon BE. Comparison of hospital resource use and outcomes among hospitalists, primary care physicians, and other generalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1781. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5824.

5. Meltzer D. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: Results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

6. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Flores A, Kurina LM, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Exploring entrustment: Housestaff autonomy and patient readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(8):791-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.013.

7. HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Austin SR, Wong Y-N, Uzzo RG, Beck JR, Egleston BL. Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Elixhauser Score work. Med Care. 2015;53(9):e65-e72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c.

9. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp#references. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. Roshetsky LM, Coltri A, Flores A, et al. No time for teaching? Inpatient attending physicians’ workload and teaching before and after the implementation of the 2003 duty hours regulations. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013;88(9):1293-1298. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829eb795.

11. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

12. Aoyama T, Kunisawa S, Fushimi K, Sawa T, Imanaka Y. Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment outcomes for type A aortic dissection in elderly patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-018-0814-6.

13. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067423.

14. Yergan J, Flood AB, Diehr P, LoGerfo JP. Relationship between patient source of payment and the intensity of hospital services. Med Care. 1988;26(11):1111-1114. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198811000-00009.

15. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDCR INPT HOSP 1.; 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics/2013/Downloads/MDCR_UTIL/CPS_MDCR_INPT_HOSP_1.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

Inpatient consultation is an extremely common practice with the potential to improve patient outcomes significantly.1-3 However, variability in consultation practices may be risky for patients. In addition to underuse when the benefit is clear, the overuse of consultation may lead to additional testing and therapies, increased length of stay (LOS) and costs, conflicting recommendations, and opportunities for communication breakdown.

Consultation use is often at the discretion of individual providers. While this decision is frequently driven by patient needs, significant variation in consultation practices not fully explained by patient factors exists.1 Prior work has described hospital-level variation1 and that primary care physicians use more consultation than hospitalists.4 However, other factors affecting consultation remain unknown. We sought to explore physician-, patient-, and admission-level factors associated with consultation use on inpatient general medicine services.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project (UCHP). UCHP is a longstanding study of the care of hospitalized patients admitted to the University of Chicago general medicine services, involving both patient data collection and physician experience surveys.5 Data were obtained for enrolled UCHP patients between 2011-2016 from the Center for Research Informatics (CRI). The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

Attendings and patients consented to UCHP participation. Data collection details are described elsewhere.5,6 Data from EpicCare (EpicSystems Corp, Wisconsin) and Centricity Billing (GE Healthcare, Illinois) were obtained via CRI for all encounters of enrolled UCHP patients during the study period (N = 218,591).

Attending Attribution

We determined attending attribution for admissions as follows: the attending author of the first history and physical (H&P) was assigned. If this was unavailable, the attending author of the first progress note (PN) was assigned. For patients admitted by hospitalists on admitting shifts to nonteaching services (ie, service without residents/students), the author of the first PN was assigned if different from H&P. Where available, attribution was corroborated with call schedules.

Sample and Variables

All encounters containing inpatient admissions to the University of Chicago from May 10, 2011 (Electronic Health Record activation date), through December 31, 2016, were considered for inclusion (N = 51,171, Appendix 1). Admissions including only documentation from ancillary services were excluded (eg, encounters for hemodialysis or physical therapy). Admissions were limited to a length of stay (LOS) ≤ 5 days, corresponding to the average US inpatient LOS of 4.6 days,7 to minimize the likelihood of attending handoffs (N = 31,592). If attending attribution was not possible via the above-described methods, the admission was eliminated (N = 3,103; 10.9% of admissions with LOS ≤ 5 days). Finally, the sample was restricted to general medicine service admissions under attendings enrolled in UCHP who completed surveys. After the application of all criteria, 6,153 admissions remained for analysis.

The outcome variable was the number of consultations per admission, determined by counting the unique number of services creating clinical documentation, and subtracting one for the primary team. If the Medical/Surgical intensive care unit (ICU) was a service, then two were subtracted to account for the ICU transfer.

Attending years in practice (ie, years since medical school graduation) and gender were determined from public resources. Practice characteristics were determined from UCHP attending surveys, which address perceptions of workload and satisfaction (Appendix 2).

Patient characteristics (gender, age, Elixhauser Indices) and admission characteristics (LOS, season of admission, payor) were determined from UCHP and CRI data. The Elixhauser Index uses a well-validated system combining the presence/absence of 31 comorbidities to predict mortality and 30-day readmission.8 Elixhauser Indices were calculated using the “Creation of Elixhauser Comorbidity Index Scores 1.0” software.9 For admissions under hospitalist attendings, teaching/nonteaching team was ascertained via internal teaching service calendars.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine demographic characteristics. The difference between the lowest and highest quartile consultation use was determined via a two-sample t test. Given the multilevel nature of our count data, we used a mixed-effects Poisson model accounting for within-group variation by clustering on attending and patient (3-level random-effects model). The analysis was done using Stata 15 (StataCorp, Texas).

RESULTS

From 2011 to 2016, 14,848 patients and 88 attendings were enrolled in UCHP; 4,772 patients (32%) and 69 attendings (59.4%) had data available and were included. Mean LOS was 3.0 days (SD = 1.3). Table 1 describes the characteristics of attendings, patients, and admissions.

Seventy-six percent of admissions included at least one consultation. Consultation use varied widely, ranging from 0 to 10 per admission (mean = 1.39, median = 1; standard deviation [SD] = 1.17). The number of consultations per admission in the highest quartile of consultation frequency (mean = 3.47, median = 3) was 5.7-fold that of the lowest quartile (mean = 0.613, median = 1; P <.001).

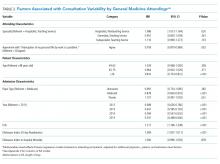

In multivariable regression, physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics were associated with the differential use of consultation (Table 2). On teaching services, consultations called by hospitalist vs nonhospitalist generalists did not differ (P =.361). However, hospitalists on nonteaching services called 8.6% more consultations than hospitalists on teaching services (P =.02). Attending agreement with survey item “The interruption of my personal life by work is a problem” was associated with 8.2% fewer consultations per admission (P =.002).

Patients older than 75 years received 19% fewer consultations compared with patients younger than 49 years (P <.001). Compared with Medicare, Medicaid admissions had 12.2% fewer consultations (P <.001), whereas privately insured admissions had 10.7% more (P =.001). The number of consultations per admission decreased every year, with 45.3% fewer consultations in 2015 than 2011 (P <.001). Consultations increased by each 22% per day increase in LOS (P <.001).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis described several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics associated with the use of inpatient consultation. Our results strengthen prior work demonstrating that patient-level factors alone are insufficient to explain consultation variability.1

Hospitalists on nonteaching services called more consultations, which may reflect a higher workload on these services. Busy hospitalists on nonteaching teams may lack time to delve deeply into clinical problems and require more consultations, especially for work with heavy cognitive loads such as diagnosis. “Outsourcing” tasks when workload increases occurs in other cognitive activities such as teaching.10 The association between work interrupting personal life and fewer consultations may also implicate the effects of time. Attendings who are experiencing work encroaching on their personal lives may be those spending more time with patients and consulting less. This finding merits further study, especially with increasing concern about balancing time spent in meaningful patient care activities with risk of physician burnout.

This finding could also indicate that trainee participation modifies consultation use for hospitalists. Teaching service teams with more individual members may allow a greater pool of collective knowledge, decreasing the need for consultation to answer clinical questions.11 Interestingly, there was no difference in consultation use between generalists or subspecialists and hospitalists on teaching services, possibly suggesting a unique effect in hospitalists who vary clinical practice depending on team structure. These differences deserve further investigation, with implications for education and resource utilization.

We were surprised by the finding that consultations decreased each year, despite increasing patient complexity and availability of consultation services. This could be explained by a growing emphasis on shortening LOS in our institution, thus shifting consultative care to outpatient settings. Understanding these effects is critically important with growing evidence that consultation improves patient outcomes because these external pressures could lead to unintended consequences for quality or access to care.

Several findings related to patient factors additionally emerged, including age and insurance status. Although related to medical complexity, these effects persist despite adjustment, which raises the question of whether they contribute to the decision to seek consultation. Older patients received fewer consultations, which could reflect the use of more conservative practice models in the elderly,12 or ageism, which is associated with undertreatment.13 With respect to insurance status, Medicaid patients were associated with fewer consultations. This finding is consistent with previous work showing the decreased intensity of hospital services used for Medicaid patients.14Our study has limitations. Our data were from one large urban academic center that limits generalizability. Although systematic and redundant, attending attribution may have been flawed: incomplete or erroneous documentation could have led to attribution error, and we cannot rule out the possibility of service handoffs. We used a LOS ≤ 5 days to minimize this possibility, but this limits the applicability of our findings to longer admissions. Unsurprisingly, longer LOS correlated with the increased use of consultation even within our restricted sample, and future work should examine the effects of prolonged LOS. As a retrospective analysis, unmeasured confounders due to our limited adjustment will likely explain some findings, although we took steps to address this in our statistical design. Finally, we could not measure patient outcomes and, therefore, cannot determine the value of more or fewer consultations for specific patients or illnesses. Positive and negative outcomes of increased consultation are described, and understanding the impact of consultation is critical for further study.2,3

CONCLUSION

We found that the use of consultation on general medicine services varies widely between admissions, with large differences between the highest and lowest frequencies of use. This variation can be partially explained by several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics. Our work may help identify patient and attending groups at high risk for under- or overuse of consultation and guide the subsequent development of interventions to improve value in consultation. One additional consultation over the average LOS of 4.6 days adds $420 per admission or $4.8 billion to the 11.5 million annual Medicare admissions.15 Increasing research, guidelines, and education on the judicious use of inpatient consultation will be key in maximizing high-value care and improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable support and assistance of the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, the Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program, the University of Chicago Center for Quality, and the University of Chicago Center for Health and the Social Sciences (CHeSS). The authors would additionally like to thank John Cursio, PhD, for his support and guidance in statistical analysis for this project.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Preliminary results of this analysis were presented at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript. The submission is not under review by any other publication.

Inpatient consultation is an extremely common practice with the potential to improve patient outcomes significantly.1-3 However, variability in consultation practices may be risky for patients. In addition to underuse when the benefit is clear, the overuse of consultation may lead to additional testing and therapies, increased length of stay (LOS) and costs, conflicting recommendations, and opportunities for communication breakdown.

Consultation use is often at the discretion of individual providers. While this decision is frequently driven by patient needs, significant variation in consultation practices not fully explained by patient factors exists.1 Prior work has described hospital-level variation1 and that primary care physicians use more consultation than hospitalists.4 However, other factors affecting consultation remain unknown. We sought to explore physician-, patient-, and admission-level factors associated with consultation use on inpatient general medicine services.

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective analysis of data from the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project (UCHP). UCHP is a longstanding study of the care of hospitalized patients admitted to the University of Chicago general medicine services, involving both patient data collection and physician experience surveys.5 Data were obtained for enrolled UCHP patients between 2011-2016 from the Center for Research Informatics (CRI). The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Data Collection

Attendings and patients consented to UCHP participation. Data collection details are described elsewhere.5,6 Data from EpicCare (EpicSystems Corp, Wisconsin) and Centricity Billing (GE Healthcare, Illinois) were obtained via CRI for all encounters of enrolled UCHP patients during the study period (N = 218,591).

Attending Attribution

We determined attending attribution for admissions as follows: the attending author of the first history and physical (H&P) was assigned. If this was unavailable, the attending author of the first progress note (PN) was assigned. For patients admitted by hospitalists on admitting shifts to nonteaching services (ie, service without residents/students), the author of the first PN was assigned if different from H&P. Where available, attribution was corroborated with call schedules.

Sample and Variables

All encounters containing inpatient admissions to the University of Chicago from May 10, 2011 (Electronic Health Record activation date), through December 31, 2016, were considered for inclusion (N = 51,171, Appendix 1). Admissions including only documentation from ancillary services were excluded (eg, encounters for hemodialysis or physical therapy). Admissions were limited to a length of stay (LOS) ≤ 5 days, corresponding to the average US inpatient LOS of 4.6 days,7 to minimize the likelihood of attending handoffs (N = 31,592). If attending attribution was not possible via the above-described methods, the admission was eliminated (N = 3,103; 10.9% of admissions with LOS ≤ 5 days). Finally, the sample was restricted to general medicine service admissions under attendings enrolled in UCHP who completed surveys. After the application of all criteria, 6,153 admissions remained for analysis.

The outcome variable was the number of consultations per admission, determined by counting the unique number of services creating clinical documentation, and subtracting one for the primary team. If the Medical/Surgical intensive care unit (ICU) was a service, then two were subtracted to account for the ICU transfer.

Attending years in practice (ie, years since medical school graduation) and gender were determined from public resources. Practice characteristics were determined from UCHP attending surveys, which address perceptions of workload and satisfaction (Appendix 2).

Patient characteristics (gender, age, Elixhauser Indices) and admission characteristics (LOS, season of admission, payor) were determined from UCHP and CRI data. The Elixhauser Index uses a well-validated system combining the presence/absence of 31 comorbidities to predict mortality and 30-day readmission.8 Elixhauser Indices were calculated using the “Creation of Elixhauser Comorbidity Index Scores 1.0” software.9 For admissions under hospitalist attendings, teaching/nonteaching team was ascertained via internal teaching service calendars.

Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to examine demographic characteristics. The difference between the lowest and highest quartile consultation use was determined via a two-sample t test. Given the multilevel nature of our count data, we used a mixed-effects Poisson model accounting for within-group variation by clustering on attending and patient (3-level random-effects model). The analysis was done using Stata 15 (StataCorp, Texas).

RESULTS

From 2011 to 2016, 14,848 patients and 88 attendings were enrolled in UCHP; 4,772 patients (32%) and 69 attendings (59.4%) had data available and were included. Mean LOS was 3.0 days (SD = 1.3). Table 1 describes the characteristics of attendings, patients, and admissions.

Seventy-six percent of admissions included at least one consultation. Consultation use varied widely, ranging from 0 to 10 per admission (mean = 1.39, median = 1; standard deviation [SD] = 1.17). The number of consultations per admission in the highest quartile of consultation frequency (mean = 3.47, median = 3) was 5.7-fold that of the lowest quartile (mean = 0.613, median = 1; P <.001).

In multivariable regression, physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics were associated with the differential use of consultation (Table 2). On teaching services, consultations called by hospitalist vs nonhospitalist generalists did not differ (P =.361). However, hospitalists on nonteaching services called 8.6% more consultations than hospitalists on teaching services (P =.02). Attending agreement with survey item “The interruption of my personal life by work is a problem” was associated with 8.2% fewer consultations per admission (P =.002).

Patients older than 75 years received 19% fewer consultations compared with patients younger than 49 years (P <.001). Compared with Medicare, Medicaid admissions had 12.2% fewer consultations (P <.001), whereas privately insured admissions had 10.7% more (P =.001). The number of consultations per admission decreased every year, with 45.3% fewer consultations in 2015 than 2011 (P <.001). Consultations increased by each 22% per day increase in LOS (P <.001).

DISCUSSION

Our analysis described several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics associated with the use of inpatient consultation. Our results strengthen prior work demonstrating that patient-level factors alone are insufficient to explain consultation variability.1

Hospitalists on nonteaching services called more consultations, which may reflect a higher workload on these services. Busy hospitalists on nonteaching teams may lack time to delve deeply into clinical problems and require more consultations, especially for work with heavy cognitive loads such as diagnosis. “Outsourcing” tasks when workload increases occurs in other cognitive activities such as teaching.10 The association between work interrupting personal life and fewer consultations may also implicate the effects of time. Attendings who are experiencing work encroaching on their personal lives may be those spending more time with patients and consulting less. This finding merits further study, especially with increasing concern about balancing time spent in meaningful patient care activities with risk of physician burnout.

This finding could also indicate that trainee participation modifies consultation use for hospitalists. Teaching service teams with more individual members may allow a greater pool of collective knowledge, decreasing the need for consultation to answer clinical questions.11 Interestingly, there was no difference in consultation use between generalists or subspecialists and hospitalists on teaching services, possibly suggesting a unique effect in hospitalists who vary clinical practice depending on team structure. These differences deserve further investigation, with implications for education and resource utilization.

We were surprised by the finding that consultations decreased each year, despite increasing patient complexity and availability of consultation services. This could be explained by a growing emphasis on shortening LOS in our institution, thus shifting consultative care to outpatient settings. Understanding these effects is critically important with growing evidence that consultation improves patient outcomes because these external pressures could lead to unintended consequences for quality or access to care.

Several findings related to patient factors additionally emerged, including age and insurance status. Although related to medical complexity, these effects persist despite adjustment, which raises the question of whether they contribute to the decision to seek consultation. Older patients received fewer consultations, which could reflect the use of more conservative practice models in the elderly,12 or ageism, which is associated with undertreatment.13 With respect to insurance status, Medicaid patients were associated with fewer consultations. This finding is consistent with previous work showing the decreased intensity of hospital services used for Medicaid patients.14Our study has limitations. Our data were from one large urban academic center that limits generalizability. Although systematic and redundant, attending attribution may have been flawed: incomplete or erroneous documentation could have led to attribution error, and we cannot rule out the possibility of service handoffs. We used a LOS ≤ 5 days to minimize this possibility, but this limits the applicability of our findings to longer admissions. Unsurprisingly, longer LOS correlated with the increased use of consultation even within our restricted sample, and future work should examine the effects of prolonged LOS. As a retrospective analysis, unmeasured confounders due to our limited adjustment will likely explain some findings, although we took steps to address this in our statistical design. Finally, we could not measure patient outcomes and, therefore, cannot determine the value of more or fewer consultations for specific patients or illnesses. Positive and negative outcomes of increased consultation are described, and understanding the impact of consultation is critical for further study.2,3

CONCLUSION

We found that the use of consultation on general medicine services varies widely between admissions, with large differences between the highest and lowest frequencies of use. This variation can be partially explained by several physician-, patient-, and admission-level characteristics. Our work may help identify patient and attending groups at high risk for under- or overuse of consultation and guide the subsequent development of interventions to improve value in consultation. One additional consultation over the average LOS of 4.6 days adds $420 per admission or $4.8 billion to the 11.5 million annual Medicare admissions.15 Increasing research, guidelines, and education on the judicious use of inpatient consultation will be key in maximizing high-value care and improving patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the invaluable support and assistance of the University of Chicago Hospitalist Project, the Pritzker School of Medicine Summer Research Program, the University of Chicago Center for Quality, and the University of Chicago Center for Health and the Social Sciences (CHeSS). The authors would additionally like to thank John Cursio, PhD, for his support and guidance in statistical analysis for this project.

Disclaimer

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. The funders had no role in the design of the study; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or the decision to approve publication of the finished manuscript. Preliminary results of this analysis were presented at the 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida. All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of the manuscript. The submission is not under review by any other publication.

1. Stevens JP, Nyweide D, Maresh S, et al. Variation in inpatient consultation among older adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):992-999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3216-7.

2. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, Schwartzman J, Kirkland K. Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(5):263-267. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181b8fccb.

3. Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2011;30(3):454-463. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929.

4. Stevens JP, Nyweide DJ, Maresh S, Hatfield LA, Howell MD, Landon BE. Comparison of hospital resource use and outcomes among hospitalists, primary care physicians, and other generalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1781. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5824.

5. Meltzer D. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: Results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

6. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Flores A, Kurina LM, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Exploring entrustment: Housestaff autonomy and patient readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(8):791-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.013.

7. HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Austin SR, Wong Y-N, Uzzo RG, Beck JR, Egleston BL. Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Elixhauser Score work. Med Care. 2015;53(9):e65-e72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c.

9. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp#references. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. Roshetsky LM, Coltri A, Flores A, et al. No time for teaching? Inpatient attending physicians’ workload and teaching before and after the implementation of the 2003 duty hours regulations. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013;88(9):1293-1298. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829eb795.

11. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

12. Aoyama T, Kunisawa S, Fushimi K, Sawa T, Imanaka Y. Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment outcomes for type A aortic dissection in elderly patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-018-0814-6.

13. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067423.

14. Yergan J, Flood AB, Diehr P, LoGerfo JP. Relationship between patient source of payment and the intensity of hospital services. Med Care. 1988;26(11):1111-1114. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198811000-00009.

15. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDCR INPT HOSP 1.; 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics/2013/Downloads/MDCR_UTIL/CPS_MDCR_INPT_HOSP_1.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

1. Stevens JP, Nyweide D, Maresh S, et al. Variation in inpatient consultation among older adults in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(7):992-999. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3216-7.

2. Lahey T, Shah R, Gittzus J, Schwartzman J, Kirkland K. Infectious diseases consultation lowers mortality from Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2009;88(5):263-267. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0b013e3181b8fccb.

3. Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff Proj Hope. 2011;30(3):454-463. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929.

4. Stevens JP, Nyweide DJ, Maresh S, Hatfield LA, Howell MD, Landon BE. Comparison of hospital resource use and outcomes among hospitalists, primary care physicians, and other generalists. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1781. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.5824.

5. Meltzer D. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: Results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-137-11-200212030-00007.

6. Martin SK, Farnan JM, Flores A, Kurina LM, Meltzer DO, Arora VM. Exploring entrustment: Housestaff autonomy and patient readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(8):791-797. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.013.

7. HCUP-US NIS Overview. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Accessed July 7, 2017.

8. Austin SR, Wong Y-N, Uzzo RG, Beck JR, Egleston BL. Why summary comorbidity measures such as the Charlson Comorbidity Index and Elixhauser Score work. Med Care. 2015;53(9):e65-e72. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e318297429c.

9. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. Elixhauser Comorbidity Software. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp#references. Accessed May 13, 2019.

10. Roshetsky LM, Coltri A, Flores A, et al. No time for teaching? Inpatient attending physicians’ workload and teaching before and after the implementation of the 2003 duty hours regulations. Acad Med J Assoc Am Med Coll. 2013;88(9):1293-1298. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829eb795.

11. Barnett ML, Boddupalli D, Nundy S, Bates DW. Comparative accuracy of diagnosis by collective intelligence of multiple physicians vs individual physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190096. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0096.

12. Aoyama T, Kunisawa S, Fushimi K, Sawa T, Imanaka Y. Comparison of surgical and conservative treatment outcomes for type A aortic dissection in elderly patients. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2018;13(1):129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-018-0814-6.

13. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(8):762-774. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa067423.

14. Yergan J, Flood AB, Diehr P, LoGerfo JP. Relationship between patient source of payment and the intensity of hospital services. Med Care. 1988;26(11):1111-1114. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-198811000-00009.

15. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. MDCR INPT HOSP 1.; 2008. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/CMSProgramStatistics/2013/Downloads/MDCR_UTIL/CPS_MDCR_INPT_HOSP_1.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Measuring Patient Experiences

The hospitalized patient experience has become an area of increased focus for hospitals given the recent coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.[1] Although patient experiences are multifactorial, 1 component is the relationship that hospitalized patients develop with their inpatient physicians. In recognition of the importance of this relationship, several organizations including the Society of Hospital Medicine, Society of General Internal Medicine, American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have recommended that patients know and understand who is guiding their care at all times during their hospitalization.[2, 3] Unfortunately, previous studies have shown that hospitalized patients often lack the ability to identify[4, 5] and understand their course of care.[6, 7] This may be due to numerous clinical factors including lack of a prior relationship, rapid pace of clinical care, and the frequent transitions of care found in both hospitalists and general medicine teaching services.[5, 8, 9] Regardless of the cause, one could hypothesize that patients who are unable to identify or understand the role of their physician may be less informed about their hospitalization, which may lead to further confusion, dissatisfaction, and ultimately a poor experience.

Given the proliferation of nonteaching hospitalist services in teaching hospitals, it is important to understand if patient experiences differ between general medicine teaching and hospitalist services. Several reasons could explain why patient experiences may vary on these services. For example, patients on a hospitalist service will likely interact with a single physician caretaker, which may give a feeling of more personalized care. In contrast, patients on general medicine teaching services are cared for by larger teams of residents under the supervision of an attending physician. Residents are also subjected to duty‐hour restrictions, clinic responsibilities, and other educational requirements that may impede the continuity of care for hospitalized patients.[10, 11, 12] Although 1 study has shown that hospitalist‐intensive hospitals perform better on patient satisfaction measures,[13] no study to date has compared patient‐reported experiences on general medicine teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services. This study aimed to evaluate the hospitalized patient experience on both teaching and nonteaching hospitalist services by assessing several patient‐reported measures of their experience, namely their confidence in their ability to identify their physician(s), understand their roles, and their rating of both the coordination and overall care.

METHODS

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort analysis at the University of Chicago Medical Center between July 2007 and June 2013. Data were acquired as part of the Hospitalist Project, an ongoing study that is used to evaluate the impact of hospitalists, and now serves as infrastructure to continue research related to hospital care at University of Chicago.[14] Patients were cared for by either the general medicine teaching service or the nonteaching hospitalist service. General medicine teaching services were composed of an attending physician who rotates for 2 weeks at a time, a second‐ or third‐year medicine resident, 1 to 2 medicine interns, and 1 to 2 medical students.[15] The attending physician assigned to the patient's hospitalization was the attending listed on the first day of hospitalization, regardless of the length of hospitalization. Nonteaching hospitalist services consisted of a single hospitalist who worked 7‐day shifts, and were assisted by a nurse practitioner/physician's assistant (NPA). The majority of attendings on the hospitalist service were less than 5 years out of residency. Both services admitted 7 days a week, with patients initially admitted to the general medicine teaching service until resident caps were met, after which all subsequent admissions were admitted to the hospitalist service. In addition, the hospitalist service is also responsible for specific patient subpopulations, such as lung and renal transplants, and oncologic patients who have previously established care with our institution.

Data Collection

During a 30‐day posthospitalization follow‐up questionnaire, patients were surveyed regarding their confidence in their ability to identify and understand the roles of their physician(s) and their perceptions of the overall coordination of care and their overall care, using a 5‐point Likert scale (1 = poor understanding to 5 = excellent understanding). Questions related to satisfaction with care and coordination were derived from the Picker‐Commonwealth Survey, a previously validated survey meant to evaluate patient‐centered care.[16] Patients were also asked to report their race, level of education, comorbid diseases, and whether they had any prior hospitalizations within 1 year. Chart review was performed to obtain patient age, gender, and hospital length of stay (LOS), and calculated Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI).[17] Patients with missing data or responses to survey questions were excluded from final analysis. The University of Chicago Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, and all patients provided written consented prior to participation.

Data Analysis

After initial analysis noted that outcomes were skewed, the decision was made to dichotomize the data and use logistic rather than linear regression models. Patient responses to the follow‐up phone questionnaire were dichotomized to reflect the top 2 categories (excellent and very good). Pearson 2 analysis was used to assess for any differences in demographic characteristics, disease severity, and measures of patient experience between the 2 services. To assess if service type was associated with differences in our 4 measures of patient experience, we created a 3‐level mixed‐effects logistic regression using a logit function while controlling for age, gender, race, CCI, LOS, previous hospitalizations within 1 year, level of education, and academic year. These models studied the longitudinal association between teaching service and the 4 outcome measures, while also controlling for the cluster effect of time nested within individual patients who were clustered within physicians. The model included random intercepts at both the patient and physician level and also included a random effect of service (teaching vs nonteaching) at the patient level. A Hausman test was used to determine if these random‐effects models improved fit over a fixed‐effects model, and the intraclass correlations were compared using likelihood ratio tests to determine the appropriateness of a 3‐level versus 2‐level model. Data management and 2 analyses were performed using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and mixed‐effects regression models were done in SuperMix (Scientific Software International, Skokie, IL).

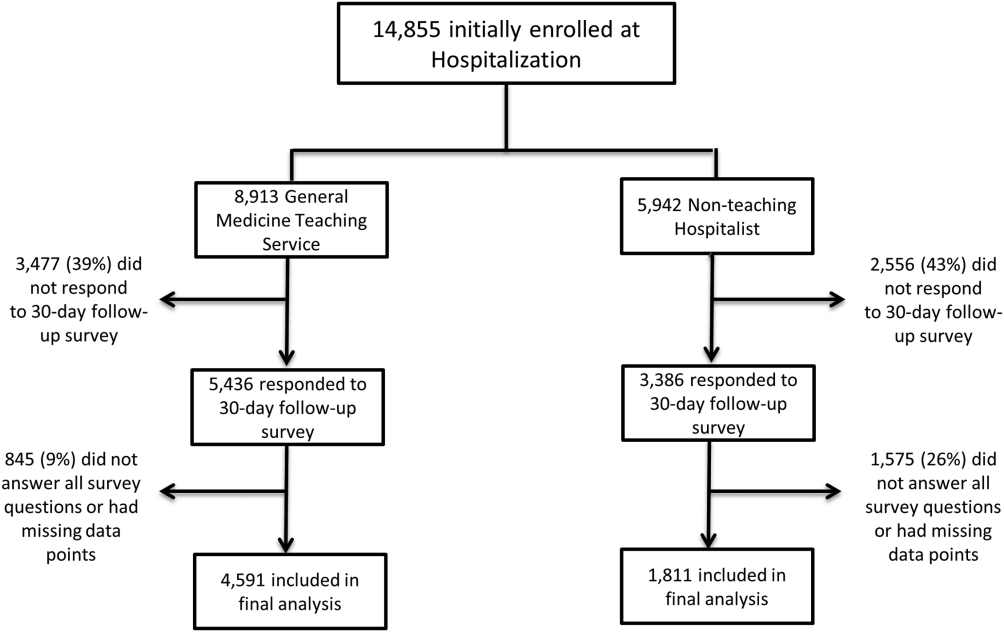

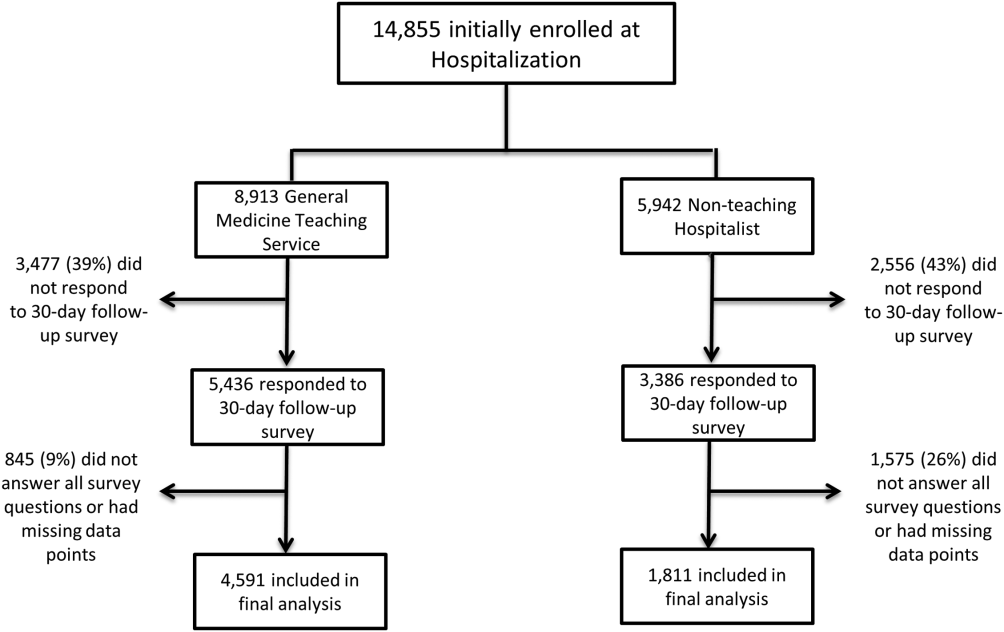

RESULTS

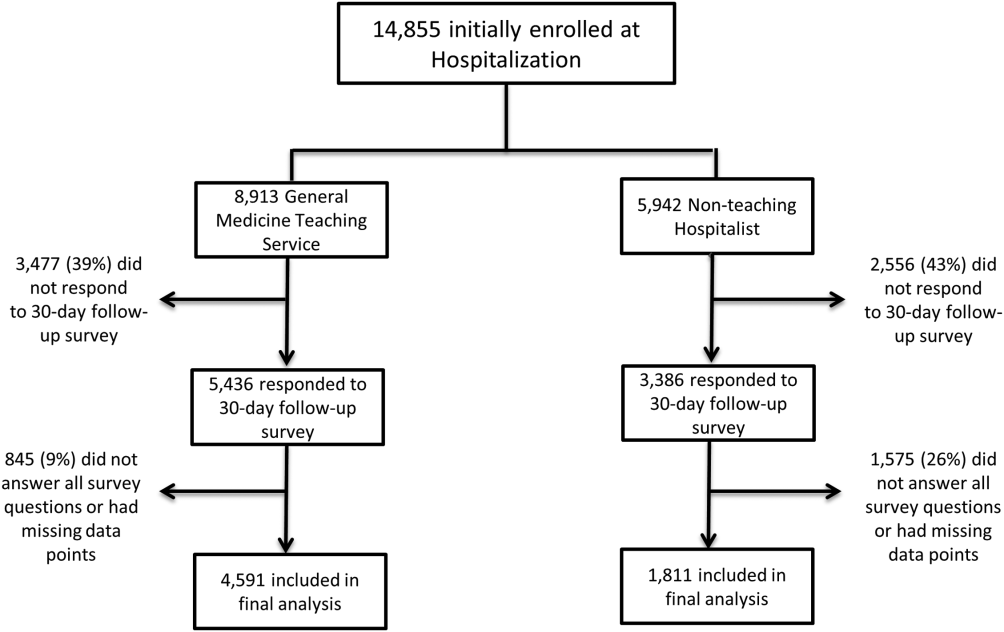

In total, 14,855 patients were enrolled during their hospitalization with 57% and 61% completing the 30‐day follow‐up survey on the hospitalist and general medicine teaching service, respectively. In total, 4131 (69%) and 4322 (48%) of the hospitalist and general medicine services, respectively, either did not answer all survey questions, or were missing basic demographic data, and thus were excluded. Data from 4591 patients on the general medicine teaching (52% of those enrolled at hospitalization) and 1811 on the hospitalist service (31% of those enrolled at hospitalization) were used for final analysis (Figure 1). Respondents were predominantly female (61% and 56%), African American (75% and 63%), with a mean age of 56.2 (19.4) and 57.1 (16.1) years, for the general medicine teaching and hospitalist services, respectively. A majority of patients (71% and 66%) had a CCI of 0 to 3 on both services. There were differences in self‐reported comorbidities between the 2 groups, with hospitalist services having a higher prevalence of cancer (20% vs 7%), renal disease (25% vs 18%), and liver disease (23% vs 7%). Patients on the hospitalist service had a longer mean LOS (5.5 vs 4.8 days), a greater percentage of a hospitalization within 1 year (58% vs 52%), and a larger proportion who were admitted in 2011 to 2013 compared to 2007 to 2010 (75% vs 39%), when compared to the general medicine teaching services. Median LOS and interquartile ranges were similar between both groups. Although most baseline demographics were statistically different between the 2 groups (Table 1), these differences were likely clinically insignificant. Compared to those who responded to the follow‐up survey, nonresponders were more likely to be African American (73% and 64%, P < 0.001) and female (60% and 56%, P < 0.01). The nonresponders were more likely to be hospitalized in the past 1 year (62% and 53%, P < 0.001) and have a lower CCI (CCI 03 [75% and 80%, P < 0.001]) compared to responders. Demographics between responders and nonresponders were also statistically different from one another.

| Variable | General Medicine Teaching | Nonteaching Hospitalist | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Total (n) | 4,591 | 1,811 | <0.001 |

| Attending classification, hospitalist, n (%) | 1,147 (25) | 1,811 (100) | |

| Response rate, % | 61 | 57 | <0.01 |

| Age, y, mean SD | 56.2 19.4 | 57.1 16.1 | <0.01 |

| Gender, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| Male | 1,796 (39) | 805 (44) | |

| Female | 2,795 (61) | 1,004 (56) | |

| Race, n (%) | <0.01 | ||

| African American | 3,440 (75) | 1,092 (63) | |

| White | 900 (20) | 571 (32) | |

| Asian/Pacific | 38 (1) | 17 (1) | |

| Other | 20 (1) | 10 (1) | |

| Unknown | 134 (3) | 52 (3) | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 0 | 1,635 (36) | 532 (29) | |

| 12 | 1,590 (35) | 675 (37) | |

| 39 | 1,366 (30) | 602 (33) | |

| Self‐reported comorbidities | |||

| Anemia/sickle cell disease | 1,201 (26) | 408 (23) | 0.003 |

| Asthma/COPD | 1,251 (28) | 432 (24) | 0.006 |

| Cancer* | 300 (7) | 371 (20) | <0.001 |

| Depression | 1,035 (23) | 411 (23) | 0.887 |

| Diabetes | 1,381 (30) | 584 (32) | 0.087 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1,140 (25) | 485 (27) | 0.104 |

| Cardiac | 1,336 (29) | 520 (29) | 0.770 |

| Hypertension | 2,566 (56) | 1,042 (58) | 0.222 |

| HIV/AIDS | 151 (3) | 40 (2) | 0.022 |

| Kidney disease | 828 (18) | 459 (25) | <0.001 |

| Liver disease | 313 (7) | 417 (23) | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 543 (12) | 201 (11) | 0.417 |

| Education level | 0.066 | ||

| High school | 2,248 (49) | 832 (46) | |

| Junior college/college | 1,878 (41) | 781 (43) | |

| Postgraduate | 388 (8) | 173 (10) | |

| Don't know | 77 (2) | 23 (1) | |

| Academic year, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| July 2007 June 2008 | 938 (20) | 90 (5) | |

| July 2008 June 2009 | 702 (15) | 148 (8) | |

| July 2009 June 2010 | 576(13) | 85 (5) | |

| July 2010 June 2011 | 602 (13) | 138 (8) | |

| July 2011 June 2012 | 769 (17) | 574 (32) | |

| July 2012 June 2013 | 1,004 (22) | 774 (43) | |

| Length of stay, d, mean SD | 4.8 7.3 | 5.5 6.4 | <0.01 |

| Prior hospitalization (within 1 year), yes, n (%) | 2,379 (52) | 1,039 (58) | <0.01 |

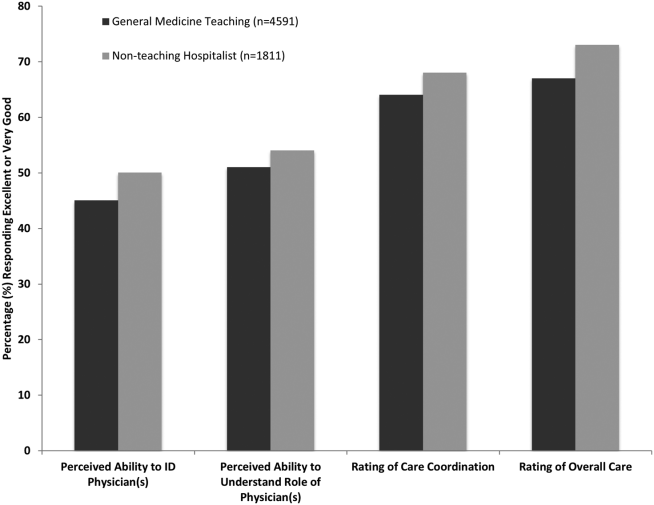

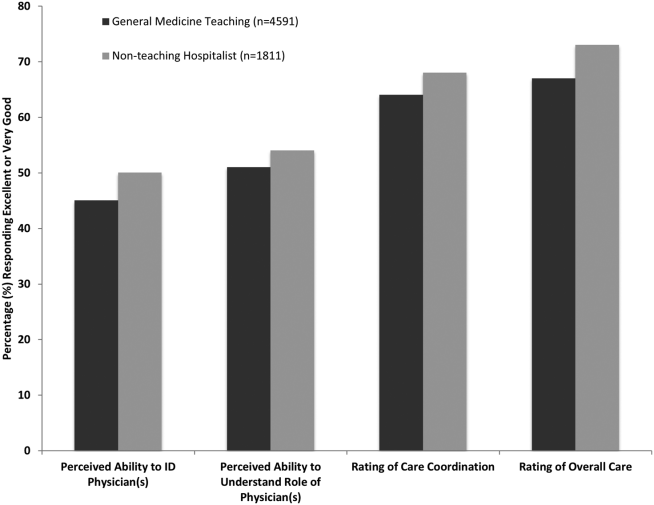

Unadjusted results revealed that patients on the hospitalist service were more confident in their abilities to identify their physician(s) (50% vs 45%, P < 0.001), perceived greater ability in understanding the role of their physician(s) (54% vs 50%, P < 0.001), and reported greater satisfaction with coordination and teamwork (68% vs 64%, P = 0.006) and with overall care (73% vs 67%, P < 0.001) (Figure 2).

From the mixed‐effects regression models it was discovered that admission to the hospitalist service was associated with a higher odds ratio (OR) of reporting overall care as excellent or very good (OR: 1.33; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.15‐1.47). There was no difference between services in patients' ability to identify their physician(s) (OR: 0.89; 95% CI: 0.61‐1.11), in patients reporting a better understanding of the role of their physician(s) (OR: 1.09; 95% CI: 0.94‐1.23), or in their rating of overall coordination and teamwork (OR: 0.71; 95% CI: 0.42‐1.89).

A subgroup analysis was performed on the 25% of hospitalist attendings in the general medicine teaching service comparing this cohort to the hospitalist services, and it was found that patients perceived better overall care on the hospitalist service (OR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.01‐ 1.31) than on the general medicine service (Table 2). All other domains in the subgroup analysis were not statistically significant. Finally, an ordinal logistic regression was performed for each of these outcomes, but it did not show any major differences compared to the logistic regression of dichotomous outcomes.

| Domains in Patient Experience* | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| How would you rate your ability to identify the physicians and trainees on your general medicine team during the hospitalization? | ||

| Model 1 | 0.89 (0.611.11) | 0.32 |

| Model 2 | 0.98 (0.671.22) | 0.86 |

| How would you rate your understanding of the roles of the physicians and trainees on your general medicine team? | ||

| Model 1 | 1.09 (0.941.23) | 0.25 |

| Model 2 | 1.19 (0.981.36) | 0.08 |

| How would you rate the overall coordination and teamwork among the doctors and nurses who care for you during your hospital stay? | ||

| Model 1 | 0.71 (0.421.89) | 0.18 |

| Model 2 | 0.82 (0.651.20) | 0.23 |

| Overall, how would you rate the care you received at the hospital? | ||

| Model 1 | 1.33 (1.151.47) | 0.001 |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (1.011.31) | 0.04 |

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to directly compare measures of patient experience on hospitalist and general medicine teaching services in a large, multiyear comparison across multiple domains. In adjusted analysis, we found that patients on nonteaching hospitalist services rated their overall care better than those on general medicine teaching services, whereas no differences in patients' ability to identify their physician(s), understand their role in their care, or rating of coordination of care were found. Although the magnitude of the differences in rating of overall care may appear small, it remains noteworthy because of the recent focus on patient experience at the reimbursement level, where small differences in performance can lead to large changes in payment. Because of the observational design of this study, it is important to consider mechanisms that could account for our findings.

The first are the structural differences between the 2 services. Our subgroup analysis comparing patients rating of overall care on a general medicine service with a hospitalist attending to a pure hospitalist cohort found a significant difference between the groups, indicating that the structural differences between the 2 groups may be a significant contributor to patient satisfaction ratings. Under the care of a hospitalist service, a patient would only interact with a single physician on a daily basis, possibly leading to a more meaningful relationship and improved communication between patient and provider. Alternatively, while on a general medicine teaching service, patients would likely interact with multiple physicians, as a result making their confidence in their ability to identify and perception at understanding physicians' roles more challenging.[18] This dilemma is further compounded by duty hour restrictions, which have subsequently led to increased fragmentation in housestaff scheduling. The patient experience on the general medicine teaching service may be further complicated by recent data that show residents spend a minority of time in direct patient care,[19, 20] which could additionally contribute to patients' inability to understand who their physicians are and to the decreased satisfaction with their care. This combination of structural complexity, duty hour reform, and reduced direct patient interaction would likely decrease the chance a patient will interact with the same resident on a consistent basis,[5, 21] thus making the ability to truly understand who their caretakers are, and the role they play, more difficult.

Another contributing factor could be the use of NPAs on our hospitalist service. Given that these providers often see the patient on a more continual basis, hospitalized patients' exposure to a single, continuous caretaker may be a factor in our findings.[22] Furthermore, with studies showing that hospitalists also spend a small fraction of their day in direct patient care,[23, 24, 25] the use of NPAs may allow our hospitalists to spend greater amounts of time with their patients, thus improving patients' rating of their overall care and influencing their perceived ability to understand their physician's role.

Although there was no difference between general medicine teaching and hospitalist services with respect to patient understanding of their roles, our data suggest that both groups would benefit from interventions to target this area. Focused attempts at improving patient's ability to identify and explain the roles of their inpatient physician(s) have been performed. For example, previous studies have attempted to improve a patient's ability to identify their physician through physician facecards[8, 9] or the use of other simple interventions (ie, bedside whiteboards).[4, 26] Results from such interventions are mixed, as they have demonstrated the capacity to improve patients' ability to identify who their physician is, whereas few have shown any appreciable improvement in patient satisfaction.[26]

Although our findings suggest that structural differences in team composition may be a possible explanation, it is also important to consider how the quality of care a patient receives affects their experience. For instance, hospitalists have been shown to produce moderate improvements in patient‐centered outcomes such as 30‐day readmission[27] and hospital length of stay[14, 28, 29, 30, 31] when compared to other care providers, which in turn could be reflected in the patient's perception of their overall care. In a large national study of acute care hospitals using the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey, Chen and colleagues found that for most measures of patient satisfaction, hospitals with greater use of hospitalist care were associated with better patient‐centered care.[13] These outcomes were in part driven by patient‐centered domains such as discharge planning, pain control, and medication management. It is possible that patients are sensitive to the improved outcomes that are associated with hospitalist services, and reflect this in their measures of patient satisfaction.

Last, because this is an observational study and not a randomized trial, it is possible that the clinical differences in the patients cared for by these services could have led to our findings. Although the clinical significance of the differences in patient demographics were small, patients seen on the hospitalist service were more likely to be older white males, with a slightly longer LOS, greater comorbidities, and more hospitalizations in the previous year than those seen on the general medicine teaching service. Additionally, our hospitalist service frequently cares for highly specific subpopulations (ie, liver and renal transplant patients, and oncology patients), which could have influenced our results. For example, transplant patients who may be very grateful for their second chance, are preferentially admitted to the hospitalist service, which could have biased our results in favor of hospitalists.[32] Unfortunately, we were unable to control for all such factors.

Although we hope that multivariable analysis can adjust for many of these differences, we are not able to account for possible unmeasured confounders such as time of day of admission, health literacy, personality differences, physician turnover, or nursing and other ancillary care that could contribute to these findings. In addition to its observational study design, our study has several other limitations. First, our study was performed at a single institution, thus limiting its generalizability. Second, as a retrospective study based on observational data, no definitive conclusions regarding causality can be made. Third, although our response rate was low, it is comparable to other studies that have examined underserved populations.[33, 34] Fourth, because our survey was performed 30 days after hospitalization, this may impart imprecision on our outcomes measures. Finally, we were not able to mitigate selection bias through imputation for missing data .

All together, given the small absolute differences between the groups in patients' ratings of their overall care compared to large differences in possible confounders, these findings call for further exploration into the significance and possible mechanisms of these outcomes. Our study raises the potential possibility that the structural component of a care team may play a role in overall patient satisfaction. If this is the case, future studies of team structure could help inform how best to optimize this component for the patient experience. On the other hand, if process differences are to explain our findings, it is important to distill the types of processes hospitalists are using to improve the patient experience and potentially export this to resident services.

Finally, if similar results were found in other institutions, these findings could have implications on how hospitals respond to new payment models that are linked to patient‐experience measures. For example, the Hospital Value‐Based Purchasing Program currently links the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services payments to a set of quality measures that consist of (1) clinical processes of care (70%) and (2) the patient experience (30%).[1] Given this linkage, any small changes in the domain of patient satisfaction could have large payment implications on a national level.

CONCLUSION

In summary, in this large‐scale multiyear study, patients cared for by a nonteaching hospitalist service reported greater satisfaction with their overall care than patients cared for by a general medicine teaching service. This difference could be mediated by the structural differences between these 2 services. As hospitals seek to optimize patient experiences in an era where reimbursement models are now being linked to patient‐experience measures, future work should focus on further understanding the mechanisms for these findings.

Disclosures

Financial support for this work was provided by the Robert Wood Johnson Investigator Program (RWJF Grant ID 63910 PI Meltzer), a Midcareer Career Development Award from the National Institute of Aging (1 K24 AG031326‐01, PI Meltzer), and a Clinical and Translational Science Award (NIH/NCATS 2UL1TR000430‐08, PI Solway, Meltzer Core Leader). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems. HCAHPS fact sheet. CAHPS hospital survey August 2013. Available at: http://www.hcahpsonline.org/files/August_2013_HCAHPS_Fact_Sheet3.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2015.

- , , , et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364–370.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common program requirements. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs2013.pdf. Accessed January 15, 2015.

- , , . Increasing a patient's ability to identify his or her attending physician using a patient room display. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1084–1085.

- , , , , , . Ability of hospitalized patients to identify their in‐hospital physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(2):199–201.

- , , , et al. Hospitalized patients' understanding of their plan of care. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(1):47–52.

- , , , et al. Patient‐physician communication at hospital discharge and patients' understanding of the postdischarge treatment plan. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(9):1026–1030.

- , , , et al. Improving inpatients' identification of their doctors: use of FACE cards. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(12):613–619.

- , , , , , . The impact of facecards on patients' knowledge, satisfaction, trust, and agreement with hospital physicians: a pilot study. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(3):137–141.

- , , . Restructuring an inpatient resident service to improve outcomes for residents, students, and patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(12):1500–1507.

- , , . Residency training in the modern era: the pipe dream of less time to learn more, care better, and be more professional. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(22):2561–2562.

- , , , , . Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(4):257–266.

- , , , . Hospitalist staffing and patient satisfaction in the national Medicare population. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(3):126–131.

- , , , et al. Effects of physician experience on costs and outcomes on an academic general medicine service: results of a trial of hospitalists. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(11):866–874.

- , , , , , . The Effects of on‐duty napping on intern sleep time and fatigue. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(11):792–798.

- , , , et al. Patients evaluate their hospital care: a national survey. Health Aff (Millwood). 1991;10(4):254–267.

- , , , . A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Welcome to HCUPnet. Available at: http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/HCUPnet.jsp?Id=F70FC59C286BADCB371(4):293–295.

- , , , et al. In the wake of the 2003 and 2011 duty hours regulations, how do internal medicine interns spend their time? J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(8):1042–1047.

- , , , , , . The composition of intern work while on call. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(11):1432–1437.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , , , et al. The impact of hospitalist discontinuity on hospital cost, readmissions, and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(7):1004–1008.

- , , , , . Hospitalist time usage and cyclicality: opportunities to improve efficiency. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):329–334.

- , , , et al. Where did the day go?—a time‐motion study of hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(6):323–328.

- , , . How hospitalists spend their time: insights on efficiency and safety. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(2):88–93.

- , , . Patient satisfaction associated with correct identification of physician's photographs. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(6):604–608.

- , , , . Comparing patient outcomes of academician‐preceptors, hospitalist‐preceptors, and hospitalists on internal medicine services in an academic medical center. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(12):1672–1678.

- , , , . Comparison of processes and outcomes of pneumonia care between hospitalists and community‐based primary care physicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77(10):1053–1058.

- , , , , , . Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2589–2600.

- . A systematic review of outcomes and quality measures in adult patients cared for by hospitalists vs nonhospitalists. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(3):248–254.

- , . Do hospitalist physicians improve the quality of inpatient care delivery? A systematic review of process, efficiency and outcome measures. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):58.

- , . Patients' experiences of everyday life after lung transplantation. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(24):3472–3479.

- , , , et al. Optimal design features for surveying low‐income populations. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2005;16(4):677–690.

The hospitalized patient experience has become an area of increased focus for hospitals given the recent coupling of patient satisfaction to reimbursement rates for Medicare patients.[1] Although patient experiences are multifactorial, 1 component is the relationship that hospitalized patients develop with their inpatient physicians. In recognition of the importance of this relationship, several organizations including the Society of Hospital Medicine, Society of General Internal Medicine, American College of Physicians, the American College of Emergency Physicians, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education have recommended that patients know and understand who is guiding their care at all times during their hospitalization.[2, 3] Unfortunately, previous studies have shown that hospitalized patients often lack the ability to identify[4, 5] and understand their course of care.[6, 7] This may be due to numerous clinical factors including lack of a prior relationship, rapid pace of clinical care, and the frequent transitions of care found in both hospitalists and general medicine teaching services.[5, 8, 9] Regardless of the cause, one could hypothesize that patients who are unable to identify or understand the role of their physician may be less informed about their hospitalization, which may lead to further confusion, dissatisfaction, and ultimately a poor experience.