User login

An Unusual Presentation of Cutaneous Metastatic Lobular Breast Carcinoma

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

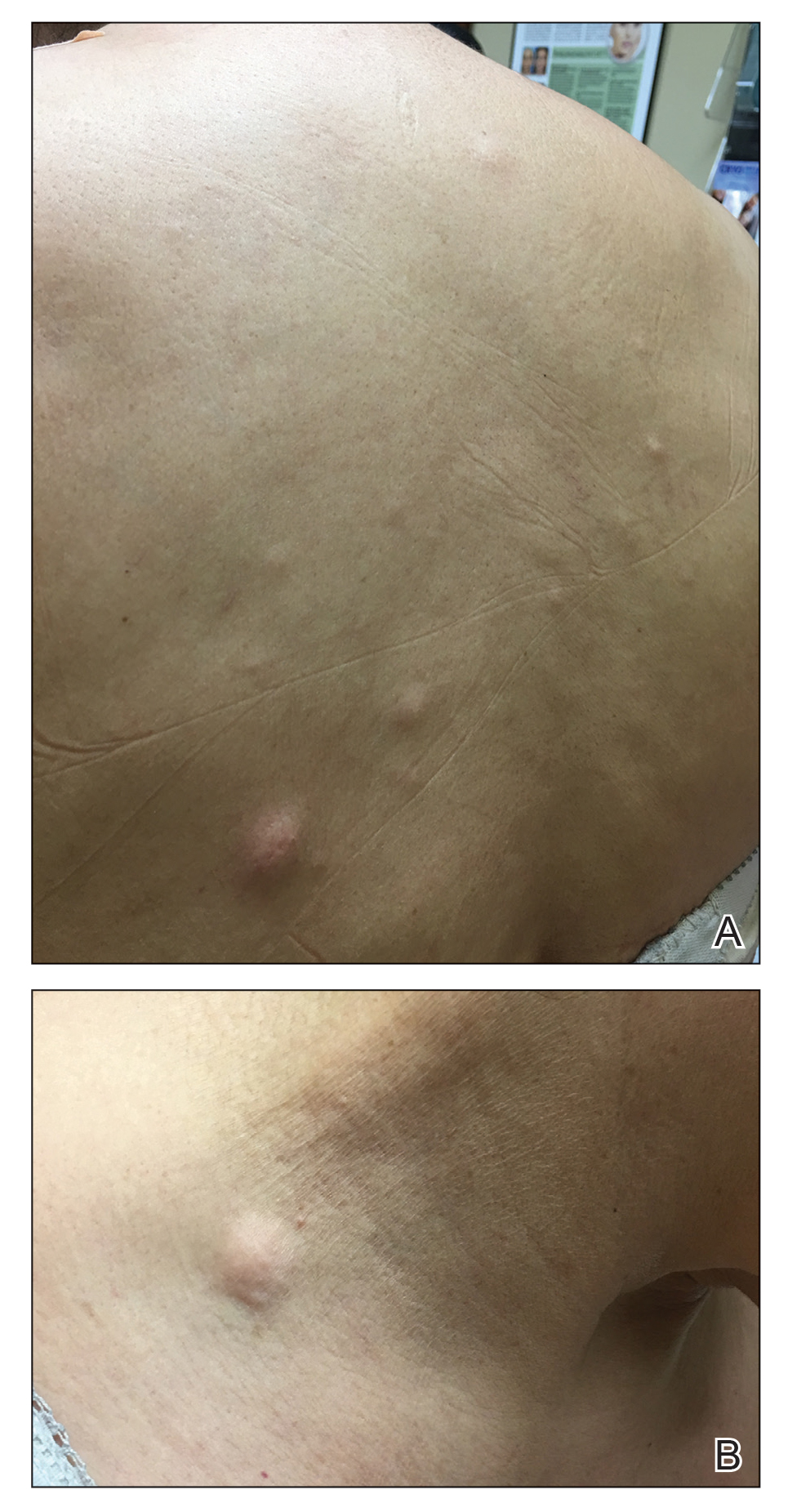

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

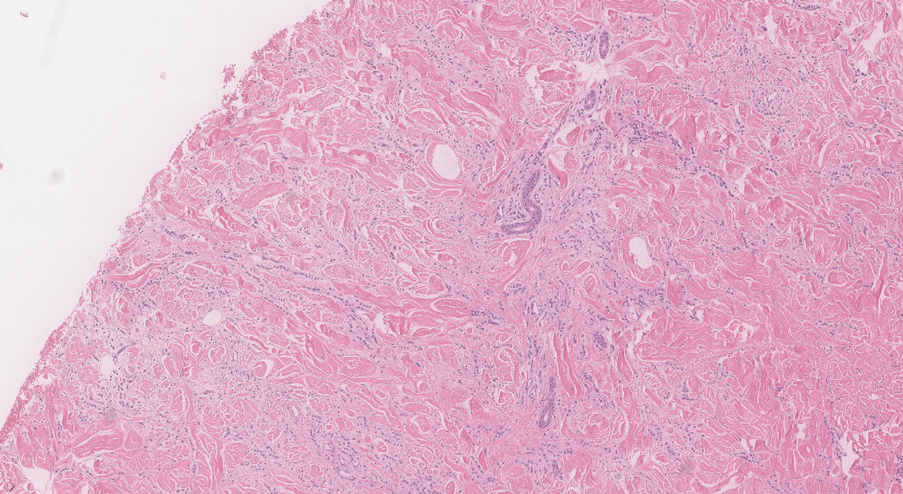

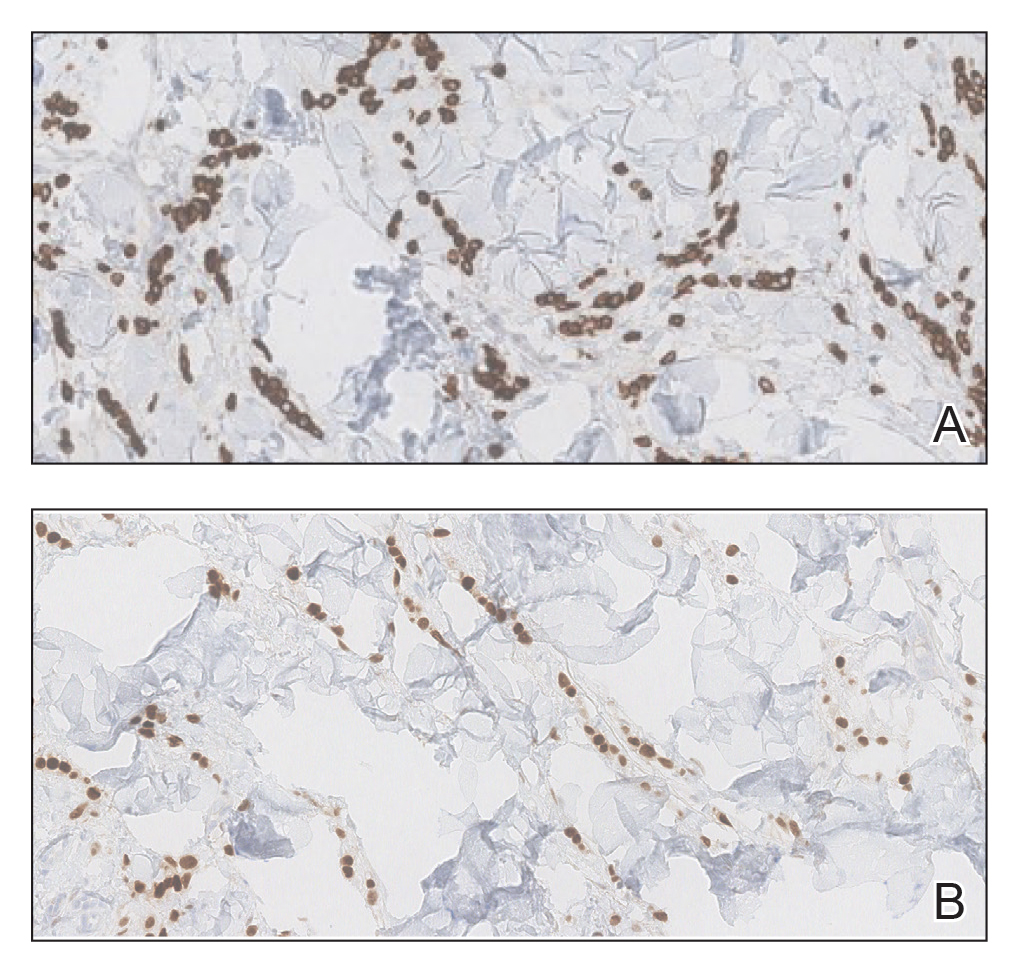

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. a retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421-1424.

- Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773-2780.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Dixon J, Anderson R, Page D, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcioma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982;6:149-161.

- Yeatman T, Cantor AB, Smith TJ, et al. Tumor biology of infiltrating lobular carcinoma: implications for management. Ann Surg. 1995;222:549-559.

- Silverstein M, Lewinski BS, Waisman JR, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma: is it different from infiltrating duct carcinoma? Cancer. 1994;73:1673-1677.

- Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046-1052.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2000;9:143-148.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

In women, breast cancer is the leading cancer diagnosis and the second leading cause of cancer-related death,1 as well as the most common malignancy to metastasize to the skin.2 Cutaneous breast carcinoma may present as cutaneous metastasis or can occur secondary to direct tumor extension. Five percent to 10% of women with breast cancer will present clinically with metastatic cutaneous disease, most commonly as a recurrence of early-stage breast carcinoma.2

In a published meta-analysis that investigated the incidence of tumors most commonly found to metastasize to the skin, Krathen et al3 found that cutaneous metastases occurred in 24% of patients with breast cancer (N=1903). In 2 large retrospective studies from tumor registry data, breast cancer was found to be the most common tumor involving metastasis to the skin, and 3.5% of the breast cancer cases identified in the registry had cutaneous metastasis as the presenting sign (n=35) at time of diagnosis.4

We report an unusual presentation of cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma that involved diffuse cutaneous lesions and rapid progression from onset of the breast mass to development of clinically apparent metastatic skin lesions.

Case Report

A 59-year-old woman with an unremarkable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of new widespread lesions that developed over a period of months. The eruption was asymptomatic and consisted of numerous bumpy lesions that reportedly started on the patient’s neck and progressively spread to involve the trunk. Physical examination revealed multiple flesh-colored, firm nodules scattered across the upper back, neck, and chest (Figure 1). Bilateral cervical and axillary lymphadenopathy also was noted. Upon questioning regarding family history of malignancy, the patient reported that her brother had been diagnosed with colon cancer. Although she was not up to date on age-appropriate malignancy screenings, she did report having a diagnostic mammogram 1 year prior that revealed a suspicious lesion on the left breast. A repeat mammogram of the left breast 6 months later was read as unremarkable.

Two 3-mm representative punch biopsies were performed. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a basket-weave stratum corneum with underlying epidermal atrophy. A relatively monomorphic epithelioid cell infiltrate extending from the superficial reticular dermis into the deep dermis and displaying an open chromatin pattern and pink cytoplasm was observed, as well as dermal collagen thickening. Linear, single-filing cells along with focal irregular nests and scattered cells were observed (Figure 2). Immunohistochemical staining was positive for cytokeratin 7 (Figure 3A), epithelial membrane antigen, and estrogen receptor (Figure 3B) along with gross cystic disease fluid protein 15; focal progesterone receptor positivity also was present. Cytokeratin 20, cytokeratin 5/6, carcinoembryonic antigen, p63, CDX2, paired box gene 8, thyroid transcription factor 1, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/neu stains were negative. Findings identified in both biopsies were consistent with metastatic cutaneous lobular breast carcinoma.

A complete blood cell count and complete metabolic panels were within normal limits, aside from a mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase level. Breast ultrasonography was unremarkable. Stereotactic breast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 9.4-cm mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast as well as enlarged lymph nodes 2.2 cm from the left axilla. A subsequent bone scan demonstrated focal activity in the left lateral fourth rib, left costochondral junction, and right anterolateral fifth rib—it was unclear whether these lesions were metastatic or secondary to trauma from a fall the patient reportedly had sustained 2 weeks prior. Lumbar MRI without gadolinium contrast revealed extensive abnormal heterogeneous signal intensity of osseous structures consistent with osseous metastasis.

Subsequent diagnostic bilateral breast ultrasonography and percutaneous left lymph node biopsy revealed pathology consistent with metastatic lobular breast carcinoma with near total effacement of the lymph node and extracapsular extension concordant with previous MRI findings. The mass in the upper outer quadrant of the right breast that previously was observed on MRI was not identifiable on this ultrasound. It was recommended that the patient pursue MRI-guided breast biopsy to have the breast lesion further characterized. She was referred to surgical oncology at a tertiary center for management; however, the patient was lost to follow-up, and there are no records available indicating the patient pursued any treatment. Although we were unable to confirm the patient’s breast lesion that previously was seen on MRI was the cause of the metastatic disease, the overall clinical picture supported metastatic lobular breast carcinoma.

Comment

Tumor metastasis to the skin accounts for approximately 2% of all skin cancers5 and typically is observed in advanced stages of cancer. In women, breast carcinoma is the most common type of cancer to exhibit this behavior.2 Invasive ductal carcinoma represents the most common histologic subtype of breast cancer overall,6,7 and breast adenocarcinomas, including lobular and ductal breast carcinomas, are the most common histologic subtypes to exhibit metastatic cutaneous lesions.8

Invasive lobular breast carcinoma represents approximately 10% of invasive breast cancer cases. Compared to invasive ductal carcinoma, there tends to be a delay in diagnosis often leading to larger tumor sizes relative to the former upon detection and with lymph node invasion. These findings may be explained by the greater difficulty of detecting invasive lobular carcinomas by mammography and clinical breast examination compared to invasive ductal carcinomas.9-11 Additionally, invasive lobular carcinomas are more likely to be positive for estrogen and progesterone receptors compared to invasive ductal carcinomas,12 which also was consistent in our case.

Cutaneous metastases of breast cancer most commonly are found on the anterior chest wall and can present as a wide spectrum of lesions, with nodules as the most common primary dermatologic manifestation.13 Cutaneous metastatic lesions commonly have been described as firm, mobile, round or oval, solitary or grouped nodules. The color of the nodules varies and may be flesh-colored, brown, blue, black, pink, and/or red-brown. The lesions often are asymptomatic but may ulcerate.2

In our case, the distribution of lesions was a unique aspect that is not typical of most cases of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinoma. The nodules appeared more scattered and involved multiple body regions, including the back, neck, and chest. Although cutaneous breast cancer metastases have been documented to extend to these body regions, a review of PubMed articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms cutaneous metastatic lobular breast carcinoma, breast carcinoma, and metastatic breast cancer suggested that it is uncommon for these multiple areas to be simultaneously affected.4,14 Rather, the more common clinical presentation of cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma is as a solitary nodule or group of nodules localized to a single anatomic region.14

Another notable feature of our case was the rapid development of the cutaneous lesions relative to the primary tumor. This patient developed diffuse lesions over a period of several months, and given that her mammogram performed the previous year was negative for any abnormalities, one could suggest that the metastatic lesions developed less than a year from onset of the primary tumor. A previous study involving 41 patients with a known clinical primary visceral malignancy (ie, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, gastric, pancreatic, kidney, thyroid, prostate, or ovarian origin) found that it takes approximately 3 years on average for cutaneous metastases to develop from the onset of cancer diagnosis (range, 1–177 months).14 In the aforementioned study, 94% of patients had stage III or IV disease at time of skin metastasis, with the majority of those demonstrating stage IV disease. However, it also is possible that these breast tumors evaded detection or were too small to be identified on prior imaging.14 A review of our patient’s medical records did not indicate documentation of any visual or palpable breast changes prior to the onset of the clinically detected metastatic nodules.

Conclusion

Biopsy with immunohistochemical staining ultimately yielded the diagnosis of metastatic lobular breast carcinoma in our patient. Providers should be aware of the varying clinical presentations that may arise in the setting of cutaneous metastasis. When faced with lesions suspicious for cutaneous metastasis, biopsy is warranted to determine the correct diagnosis and ensure appropriate management. Upon diagnosis of cutaneous metastasis, prompt coordination with the primary care provider and appropriate referral to multidisciplinary teams is necessary. Clinical providers also should maintain a high index of suspicion when evaluating patients with cutaneous metastasis who have a history of normal malignancy screenings.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. a retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421-1424.

- Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773-2780.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Dixon J, Anderson R, Page D, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcioma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982;6:149-161.

- Yeatman T, Cantor AB, Smith TJ, et al. Tumor biology of infiltrating lobular carcinoma: implications for management. Ann Surg. 1995;222:549-559.

- Silverstein M, Lewinski BS, Waisman JR, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma: is it different from infiltrating duct carcinoma? Cancer. 1994;73:1673-1677.

- Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046-1052.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2000;9:143-148.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

- American Cancer Society. Cancer facts & figures 2015. Accessed January 7, 2021. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2015/cancer-facts-and-figures-2015.pdf

- Tan AR. Cutaneous manifestations of breast cancer. Semin Oncol. 2016;43:331-334.

- Krathen RA, Orengo IF, Rosen T. Cutaneous metastasis: a meta-analysis of data. South Med J. 2003;96:164-167.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Sexton FM. Skin involvement as the presenting sign of internal carcinoma. a retrospective study of 7316 cancer patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;22:19-26.

- Alcaraz I, Cerroni L, Rutten A, et al. Cutaneous metastases from internal malignancies: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2012;34:347-393.

- Li CI, Anderson BO, Daling JR, et al. Trends in incidence rates of invasive lobular and ductal breast carcinoma. JAMA. 2003;289:1421-1424.

- Li CI, Daling JR. Changes in breast cancer incidence rates in the United States by histologic subtype and race/ethnicity, 1995 to 2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2773-2780.

- Lookingbill DP, Spangler N, Helm KF. Cutaneous metastases in patients with metastatic carcinoma: a retrospective study of 4020 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:228-236.

- Dixon J, Anderson R, Page D, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcioma of the breast. Histopathology. 1982;6:149-161.

- Yeatman T, Cantor AB, Smith TJ, et al. Tumor biology of infiltrating lobular carcinoma: implications for management. Ann Surg. 1995;222:549-559.

- Silverstein M, Lewinski BS, Waisman JR, et al. Infiltrating lobular carcinoma: is it different from infiltrating duct carcinoma? Cancer. 1994;73:1673-1677.

- Li CI, Uribe DJ, Daling JR. Clinical characteristics of different histologic types of breast cancer. Br J Cancer. 2005;93:1046-1052.

- Mordenti C, Peris K, Fargnoli M, et al. Cutaneous metastatic breast carcinoma. Acta Dermatovenerol. 2000;9:143-148.

- Sariya D, Ruth K, Adams-McDonnell R, et al. Clinicopathologic correlation of cutaneous metastases: experience from a cancer center. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:613-620.

Practice Points

- Clinical providers should be aware of the varying presentations of metastatic cutaneous breast carcinomas.

- Clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of breast cancer as a cause of cutaneous metastases, even in patients with recent negative breast cancer screening.

Surgical Procedures for Hidradenitis Suppurativa

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that has a social and psychosocial impact on patients with skin of color.1 It is characterized by recurrent abscesses, draining sinus tracts, and scarring in the intertriginous skin folds. The lesions are difficult to treat and present with considerable frustration for both patients and physicians. Although current treatment ladders can delay procedures and surgical intervention,1 some believe that surgery should be introduced earlier in HS management.2 In this article, we review current procedures for the management of HS, including cryoinsufflation, incision and drainage, deroofing, skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling, and wide surgical excision, along with various closure techniques.

Cryoinsufflation

First described in 2014, cryoinsufflation is a novel method for treating sinus tracts.3 Lesions initially are identified on physical examination. Prior to the procedure, local anesthesia is administered to the lesion.3 A 21-gauge needle is mounted onto a cryosurgical unit and inserted into the opening of the sinus tract. Liquid nitrogen is sprayed into the tract for 5 seconds, followed by a 3-second pause; the process is repeated 3 times. Patients return for treatment sessions monthly until the tract is obliterated. This procedure was first performed on 2 patients with satisfactory results.3

Since the initial report, the investigators made 2 changes to refine the procedure.4 First, systemic antibiotics should be prescribed 2 months prior to the procedure to clear the sinus tracts of infection. Furthermore, a 21-gauge, olive-tipped cannula is recommended in lieu of a 21-gauge needle to mitigate the risk of adverse events such as air embolism.4

Incision and Drainage

Incision and drainage provides rapid pain relief for tense fluctuant abscesses, but recurrence is common and the procedure costs are high.5 For drainage, wide circumferential local anesthesia is administered followed by incision.6 Pus is eliminated using digital pressure or saline rinses.2 Following the elimination of pus, the wound may need gauze packing or placement of a wick for a few days.6 The general belief is that incision and drainage should be used, if necessary, to rapidly relieve the patient’s pain; however, other surgical options should be considered if the patient has had multiple incision and drainage procedures.7 Currently there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on incision and drainage procedures in HS abscesses.

Deroofing

In 1959, Mullins et al8 first described the deroofing procedure, which was refined to preserve the floor of the sinus tract in the 1980s.9,10 Culp10 and Brown et al9 theorized that preservation of the exposed floor of the sinus tract allowed for the epithelial cells from sweat glands and hair follicle remnants to rapidly reepithelialize the wound. In 2010, van der Zee et al11 performed a prospective study of 88 deroofed lesions in which the investigators removed keratinous debris and epithelial remnants of the floor due to concern for recurrence in this area if the tissues remained. Only 17% (15/88) of the lesions recurred at a median follow-up of 34 months.11

In Hurley stage I or II HS, deroofing remains the primary procedure for persistent nodules and sinus tracts.2 The lesion is identified on physical examination and local anesthesia is administered, first to the area surrounding the lesion, then to the lesion itself.11 A blunt probe is used to identify openings and search for connecting fistulas. After defining the sinus tract, the roof and wings created by the incision are removed.11,12 The material on the floor of the tract is scraped away, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.11 In general, deroofed lesions heal with cosmetically acceptable scars. We have used this procedure in skin of color patients with good results and no difficulties with healing. Controlled trials with long-term follow-up are lacking in this population.

Skin Tissue–Saving Excision With Electrosurgical Peeling

Skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling was first introduced in 2015.13 Blok et al14 described the procedure as a promising alternative to wide surgical excision for Hurley stage II or III HS. The procedure saves healthy tissue while completely removing lesional tissue, leading to rapid wound healing, excellent cosmesis, and a low risk of contractures2,14; however, recurrence rates are higher than those seen in wide surgical excision.15 There are no known RCTs with long-term follow-up for HS patients treated with skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling.

The procedure typically is performed under general anesthesia.14 First, the sinus tract is palpated on physical examination and probed to delineate the extent of the tract. Next, the roof of the tract is incised electrosurgically with a wire loop tip coupled to an electrosurgical generator.14 Consecutive tangential excisions are made until the floor of the sinus tract is reached. The process of incising sinus tracts followed by tangential peeling off of tissue continues until the entire area is clear of lesional and fibrotic tissue. The wound margins are probed for the presence and subsequent removal of residual sinus tracts. Lastly, the electrosurgical generator is used to achieve hemostasis, steroids are injected to prevent the formation of hypergranulation tissue, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.14 Following intervention, recurrence rates appear to be similar to wide surgical excision.13,14

Wide Surgical Excision

Wide excision is a widely established technique consisting of surgical excision of a lesion plus an area of surrounding disease-free tissue such as subcutaneous fat or a lateral margin of intertriginous skin.15 Similar to other surgical techniques, wide excision is considered in cases of severe disease when pharmacologic management cannot remedy extensive fibrosis or architectural loss. It typically is performed in Hurley stage II and III HS, with pathology extending to involve deeper structures inaccessible to more superficial surgical methods.2 Prominent areas of use include gluteal, axillary, perineal, and perianal HS lesions on which conservative treatments have little effect and depend on wide excision to provide successful postoperative results.16 Although retrospective and prospective studies exist on wide excision in HS, there continues to be a dearth of RCTs. Based on the available literature, the primary motive for wide excision is lower recurrence rates (13% overall compared to 22% and 27% for local excision and deroofing, respectively) and longer asymptomatic periods compared to more local techniques.7,17 Wide excision combined with continued aggressive medical management and dietary modifications currently is an efficacious treatment in providing functional long-term results.6 These benefits, however, are not without their drawbacks, as the more extensive nature of wide surgical excision predisposes patients to larger wounds, surgery-induced infection, and prolonged recovery periods.6,15 If preoperative measurements are not wisely assessed, the excision also can extend to involve neurovascular bundles and other vital structures, contributing to greater postoperative morbidity.15 Ultrasonography provides useful anatomic information in HS, such as location and extent of fistulous tracts and fluid collections; these findings can assist in guiding the width and depth of the excision itself to ensure the entire area of HS involvement is removed.18 Published data revealed that 204 of 255 (80%) patients were markedly satisfied with postoperative outcomes of wide excision,19 which gives credence to the idea that although the complications of wide excision may not be as favorable, the long-lasting improvements in quality of life make wide surgical excision a suggested first-line treatment in all stages of HS.16,20

Closure Techniques

The best skin closure method following surgical excision is controversial and not well established in literature. Options include healing by secondary intention, primary (suture-based) closure, skin grafts, and skin flaps. Each of these methods has had moderate success in multiple observational studies, and the choice should be made based on individualized assessment of the patient’s HS lesion characteristics, ability to adhere to recovery protocols, and relevant demographics. A systematic review by Mehdizadeh et al17 provided the following recurrence rates for techniques utilized after wide excision: primary closure, 15%; flaps, 8%; and grafting, 6%. Despite conflicting evidence, allowing wounds to heal by secondary intention is best, based on the author’s experience (I.H.H.).

Secondary Intention

Healing by secondary intention refers to a wound that is intentionally left open to be filled in with granulation tissue and eventual epithelization over time rather than being approximated and closed via sutures or staples as in primary intention. It is a well-established option in wound management and results in a longer but more comfortable period of convalescence in postsurgical HS management.20 Patients can add regular moist wound dressings (eg, silastic foam dressing) to manage the wound at home and continue normal activities for most of the healing period; however, the recovery period can become excessively long and painful, and there is a high risk of formation of retractile scar bands at and around the healing site.12 Strict adherence to wound-healing protocols is paramount to minimizing unwanted complications.21 Secondary intention often is used after wide local excision and has been demonstrated to yield positive functional and aesthetic results in multiple studies, especially in the more severe Hurley stage II or III cases.21,22 It can be successfully employed after laser treatment and in surgical defects of all sizes with little to no contractures or reduced range of motion.6 Ultimately, the choice to heal via secondary intention should be made after thorough assessment of patient needs and with ample education to ensure compliance.

Primary Closure

Primary closure is the suture-mediated closing technique that is most often used in wound closure for lower-grade HS cases, especially smaller excisions. However, it is associated with potential complications. If HS lesions are not effectively excised, disease can then recur at the periphery of the excision and wound dehiscence can manifest more readily, especially as wound size increases.23 Consequently, primary closure is associated with the highest recurrence rates among closure techniques.17 Avoiding primary closure in active disease also is recommended due to the potential of burying residual foci of inflammation.6 Finally, primary closures lack skin coverage and thus often are not viable options in most perianal and genital lesions that require more extensive reconstruction. Retrospective case series and case reports exist on primary excision, but further study is needed.

Skin Grafts

Skin grafting is a technique of surgically transplanting a piece of healthy skin from one body site to another. Skin grafts typically are used when primary closure or skin flaps are not feasible (eg, in large wounds) and also when shorter time to wound closure is a greater concern in patient recovery.2,24 Additionally, skin grafts can be employed on large flat surfaces of the body, such as the buttocks or thighs, for timely wound closure when wound contraction is less effective or wound healing is slow via epithelization. Types of skin graft techniques include split-thickness skin graft (STSG), full-thickness skin graft, and recycled skin graft. All 3 types have demonstrated acceptable functional and aesthetic results in observational studies and case reports, and thus deciding which technique to use should include individualized assessment.2,25 The STSG has several advantages over the full-thickness skin graft, including hairlessness (ie, without hair follicles), ease of harvest, and a less complicated transfer to contaminated lesional areas such as those in HS.26 Additionally, STSGs allow for closure of even the largest wounds with minimal risk of serious infection. Split-thickness skin grafts are considered one of the most efficacious tools for axilla reconstruction; however, they require prolonged immobilization of the arm, result in sequelae in donor sites, and do not always prevent retractile scars.26 The recycled skin graft technique can be used to treat chronic gluteal HS, but reliability and outcomes have not been reported. Skin grafting after excision is associated with increased pain, immobilization, prolonged hospitalization, and longer healing times compared to skin flaps.19 In a systematic review of wound healing techniques following wide excision, grafting was shown to have the lowest recurrence rate (6%) compared to skin flaps (8%) and primary closure (15%).17 The absence of hair follicles and sweat glands in STSGs may be advantageous in HS because both hair follicles and sweat glands are thought to play more roles in the pathogenesis of HS.18,24 Most studies on skin grafts are limited to case reports.

Skin Flaps

Skin flaps are similar to skin grafts in that healthy skin is transplanted from one site to another; the difference is that flaps maintain an intact blood supply, whereas skin grafts depend on growth of new blood vessels.12,13 The primary advantage of skin flaps is that they provide the best quality of skin due to the thick tissue coverage, which is an important concern, especially in aesthetic scenarios. Additionally, they have been shown to provide shorter healing times than grafts, primary closure, and secondary healing, which can be especially important when functional disability is a concern in the postoperative period.26 However, their use should be limited due to several complications owing to their blood supply, as there is a high risk of ischemia to distant portions of flaps, which often can progress to necrosis and hemorrhage during the harvesting process.2 Thus, skin flaps are incredibly difficult to use in larger wounds and often require debulking due to their thickness. Additionally, skin flaps are definitive by nature, which can pose an issue if HS recurs locally. Skin flaps are recommended only when their use is mandatory, such as in the coverage of important anatomic structures (eg, exposed neurovascular bundles and large vessels).2 Advances have been made in flap construction, and now several types of flaps are employed in several body areas with differing indications and recommendations.2,21 As with skin grafts, most studies in the literature are case reports; therefore, further investigation is needed.

Combination Reconstructions

Combination reconstructions refer to the simultaneous use of multiple closure or healing techniques. By combining 2 or more methods, surgeons can utilize the advantages of each technique to provide an individualized approach that can substantially diminish wound surface area and accelerate wound healing.2 For example, with the starlike technique, 5 equilateral triangles bordering a foci of axillary disease are excised in addition to the central foci, and the edges of each triangle are then sutured together to create a final scar of considerably smaller size. The starlike technique allows the wound to be partially sutured while leaving the remaining area to heal by secondary intention.2 There are a small number of case series and prospective studies on combined reconstructions in HS but no RCTs.

Conclusion

- Smith MK, Nicholson CL, Parks-Miller A, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa: an update on connecting the tracts. F1000Res. 2017;6:1272.

- Janse I, Bieniek A, Horvath B, et al. Surgical procedures in hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:97-109.

- Pagliarello C, Fabrizi G, Feliciani C, et al. Cryoinsufflation for Hurley stage II hidradenitis suppurativa: a useful treatment option when systemic therapies should be avoided. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:765-766.

- Pagliarello C, Fabrizi G, di Nuzzo S. Cryoinsufflation for hidradenitis suppurativa: technical refinement to prevent complications. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:130-132.

- Ritz JP, Runkel N, Haier J, et al. Extent of surgery and recurrence rate of hidradenitis suppurativa. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1998;13:164-168.

- Danby FW, Hazen PG, Boer J. New and traditional surgical approaches to hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5, suppl 1):S62-S65.

- Ellis LZ. Hidradenitis suppurativa: surgical and other management techniques. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:517-536.

- Mullins JF, McCash WB, Boudreau RF. Treatment of chronic hidradenitis suppurativa: surgical modification. Postgrad Med. 1959;26:805-808.

- Brown SC, Kazzazi N, Lord PH. Surgical treatment of perineal hidradenitis suppurativa with special reference to recognition of the perianal form. Br J Surg. 1986;73:978-980.

- Culp CE. Chronic hidradenitis suppurativa of the anal canal. a surgical skin disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1983;26:669-676.

- van der Zee HH, Prens EP, Boer J. Deroofing: a tissue-saving surgical technique for the treatment of mild to moderate hidradenitis suppurativa lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:475-480.

- Lin CH, Chang KP, Huang SH. Deroofing: an effective method for treating chronic diffuse hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42:273-275.

- Blok JL, Boersma M, Terra JB, et al. Surgery under general anaes-thesia in severe hidradenitis suppurativa: a study of 363 primary operations in 113 patients. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1590-1597.

- Blok JL, Spoo JR, Leeman FW, et al. Skin-Tissue-sparing Excision with Electrosurgical Peeling (STEEP): a surgical treatment option for severe hidradenitis suppurativa Hurley stage II/III. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:379-382.

- Saunte DML, Jemec GBE. Hidradenitis suppurativa: advances in diagnosis and treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:2019-2032.

- Maghsoudi H, Almasi H, Miri Bonjar MR. Men, main victims of hidradenitis suppurativa (a prospective cohort study). Int J Surg. 2018;50:6-10.

- Mehdizadeh A, Hazen PG, Bechara FG, et al. Recurrence of hidradenitis suppurativa after surgical management: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5, suppl 1):S70-S77.

- Wortsman X, Moreno C, Soto R, et al. Ultrasound in-depth characterization and staging of hidradenitis suppurativa. Dermatol Surg. 2013;39:1835-1842.

- Kofler L, Schweinzer K, Heister M, et al. Surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: an analysis of postoperative outcome, cosmetic results and quality of life in 255 patients [published online February 17, 2018]. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. doi:10.1111/jdv.14892.

- Dini V, Oranges T, Rotella L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa and wound management. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2015;14:236-244.

- Humphries LS, Kueberuwa E, Beederman M, et al. Wide excision and healing by secondary intent for the surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa: a single-center experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:554-566.

- Wollina U, Langner D, Heinig B, et al. Comorbidities, treatment, and outcome in severe anogenital inverse acne (hidradenitis suppurativa): a 15-year single center report. Int J Dermatol. 2017;56:109-115.

- Watson JD. Hidradenitis suppurativa—a clinical review. Br J Plast Surg. 1985;38:567-569.

- Sugio Y, Tomita K, Hosokawa K. Reconstruction after excision of hidradenitis suppurativa: are skin grafts better than flaps? Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2016;4:E1128.

- Burney RE. 35-year experience with surgical treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa. World J Surg. 2017;41:2723-2730.

- Nail-Barthelemy R, Stroumza N, Qassemyar Q, et al. Evaluation of the mobility of the shoulder and quality of life after perforator flaps for recalcitrant axillary hidradenitis [published online February 13, 2018]. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. pii:S0294-1260(18)30005-0. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2018.01.003.

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that has a social and psychosocial impact on patients with skin of color.1 It is characterized by recurrent abscesses, draining sinus tracts, and scarring in the intertriginous skin folds. The lesions are difficult to treat and present with considerable frustration for both patients and physicians. Although current treatment ladders can delay procedures and surgical intervention,1 some believe that surgery should be introduced earlier in HS management.2 In this article, we review current procedures for the management of HS, including cryoinsufflation, incision and drainage, deroofing, skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling, and wide surgical excision, along with various closure techniques.

Cryoinsufflation

First described in 2014, cryoinsufflation is a novel method for treating sinus tracts.3 Lesions initially are identified on physical examination. Prior to the procedure, local anesthesia is administered to the lesion.3 A 21-gauge needle is mounted onto a cryosurgical unit and inserted into the opening of the sinus tract. Liquid nitrogen is sprayed into the tract for 5 seconds, followed by a 3-second pause; the process is repeated 3 times. Patients return for treatment sessions monthly until the tract is obliterated. This procedure was first performed on 2 patients with satisfactory results.3

Since the initial report, the investigators made 2 changes to refine the procedure.4 First, systemic antibiotics should be prescribed 2 months prior to the procedure to clear the sinus tracts of infection. Furthermore, a 21-gauge, olive-tipped cannula is recommended in lieu of a 21-gauge needle to mitigate the risk of adverse events such as air embolism.4

Incision and Drainage

Incision and drainage provides rapid pain relief for tense fluctuant abscesses, but recurrence is common and the procedure costs are high.5 For drainage, wide circumferential local anesthesia is administered followed by incision.6 Pus is eliminated using digital pressure or saline rinses.2 Following the elimination of pus, the wound may need gauze packing or placement of a wick for a few days.6 The general belief is that incision and drainage should be used, if necessary, to rapidly relieve the patient’s pain; however, other surgical options should be considered if the patient has had multiple incision and drainage procedures.7 Currently there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on incision and drainage procedures in HS abscesses.

Deroofing

In 1959, Mullins et al8 first described the deroofing procedure, which was refined to preserve the floor of the sinus tract in the 1980s.9,10 Culp10 and Brown et al9 theorized that preservation of the exposed floor of the sinus tract allowed for the epithelial cells from sweat glands and hair follicle remnants to rapidly reepithelialize the wound. In 2010, van der Zee et al11 performed a prospective study of 88 deroofed lesions in which the investigators removed keratinous debris and epithelial remnants of the floor due to concern for recurrence in this area if the tissues remained. Only 17% (15/88) of the lesions recurred at a median follow-up of 34 months.11

In Hurley stage I or II HS, deroofing remains the primary procedure for persistent nodules and sinus tracts.2 The lesion is identified on physical examination and local anesthesia is administered, first to the area surrounding the lesion, then to the lesion itself.11 A blunt probe is used to identify openings and search for connecting fistulas. After defining the sinus tract, the roof and wings created by the incision are removed.11,12 The material on the floor of the tract is scraped away, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.11 In general, deroofed lesions heal with cosmetically acceptable scars. We have used this procedure in skin of color patients with good results and no difficulties with healing. Controlled trials with long-term follow-up are lacking in this population.

Skin Tissue–Saving Excision With Electrosurgical Peeling

Skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling was first introduced in 2015.13 Blok et al14 described the procedure as a promising alternative to wide surgical excision for Hurley stage II or III HS. The procedure saves healthy tissue while completely removing lesional tissue, leading to rapid wound healing, excellent cosmesis, and a low risk of contractures2,14; however, recurrence rates are higher than those seen in wide surgical excision.15 There are no known RCTs with long-term follow-up for HS patients treated with skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling.

The procedure typically is performed under general anesthesia.14 First, the sinus tract is palpated on physical examination and probed to delineate the extent of the tract. Next, the roof of the tract is incised electrosurgically with a wire loop tip coupled to an electrosurgical generator.14 Consecutive tangential excisions are made until the floor of the sinus tract is reached. The process of incising sinus tracts followed by tangential peeling off of tissue continues until the entire area is clear of lesional and fibrotic tissue. The wound margins are probed for the presence and subsequent removal of residual sinus tracts. Lastly, the electrosurgical generator is used to achieve hemostasis, steroids are injected to prevent the formation of hypergranulation tissue, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.14 Following intervention, recurrence rates appear to be similar to wide surgical excision.13,14

Wide Surgical Excision

Wide excision is a widely established technique consisting of surgical excision of a lesion plus an area of surrounding disease-free tissue such as subcutaneous fat or a lateral margin of intertriginous skin.15 Similar to other surgical techniques, wide excision is considered in cases of severe disease when pharmacologic management cannot remedy extensive fibrosis or architectural loss. It typically is performed in Hurley stage II and III HS, with pathology extending to involve deeper structures inaccessible to more superficial surgical methods.2 Prominent areas of use include gluteal, axillary, perineal, and perianal HS lesions on which conservative treatments have little effect and depend on wide excision to provide successful postoperative results.16 Although retrospective and prospective studies exist on wide excision in HS, there continues to be a dearth of RCTs. Based on the available literature, the primary motive for wide excision is lower recurrence rates (13% overall compared to 22% and 27% for local excision and deroofing, respectively) and longer asymptomatic periods compared to more local techniques.7,17 Wide excision combined with continued aggressive medical management and dietary modifications currently is an efficacious treatment in providing functional long-term results.6 These benefits, however, are not without their drawbacks, as the more extensive nature of wide surgical excision predisposes patients to larger wounds, surgery-induced infection, and prolonged recovery periods.6,15 If preoperative measurements are not wisely assessed, the excision also can extend to involve neurovascular bundles and other vital structures, contributing to greater postoperative morbidity.15 Ultrasonography provides useful anatomic information in HS, such as location and extent of fistulous tracts and fluid collections; these findings can assist in guiding the width and depth of the excision itself to ensure the entire area of HS involvement is removed.18 Published data revealed that 204 of 255 (80%) patients were markedly satisfied with postoperative outcomes of wide excision,19 which gives credence to the idea that although the complications of wide excision may not be as favorable, the long-lasting improvements in quality of life make wide surgical excision a suggested first-line treatment in all stages of HS.16,20

Closure Techniques

The best skin closure method following surgical excision is controversial and not well established in literature. Options include healing by secondary intention, primary (suture-based) closure, skin grafts, and skin flaps. Each of these methods has had moderate success in multiple observational studies, and the choice should be made based on individualized assessment of the patient’s HS lesion characteristics, ability to adhere to recovery protocols, and relevant demographics. A systematic review by Mehdizadeh et al17 provided the following recurrence rates for techniques utilized after wide excision: primary closure, 15%; flaps, 8%; and grafting, 6%. Despite conflicting evidence, allowing wounds to heal by secondary intention is best, based on the author’s experience (I.H.H.).

Secondary Intention

Healing by secondary intention refers to a wound that is intentionally left open to be filled in with granulation tissue and eventual epithelization over time rather than being approximated and closed via sutures or staples as in primary intention. It is a well-established option in wound management and results in a longer but more comfortable period of convalescence in postsurgical HS management.20 Patients can add regular moist wound dressings (eg, silastic foam dressing) to manage the wound at home and continue normal activities for most of the healing period; however, the recovery period can become excessively long and painful, and there is a high risk of formation of retractile scar bands at and around the healing site.12 Strict adherence to wound-healing protocols is paramount to minimizing unwanted complications.21 Secondary intention often is used after wide local excision and has been demonstrated to yield positive functional and aesthetic results in multiple studies, especially in the more severe Hurley stage II or III cases.21,22 It can be successfully employed after laser treatment and in surgical defects of all sizes with little to no contractures or reduced range of motion.6 Ultimately, the choice to heal via secondary intention should be made after thorough assessment of patient needs and with ample education to ensure compliance.

Primary Closure

Primary closure is the suture-mediated closing technique that is most often used in wound closure for lower-grade HS cases, especially smaller excisions. However, it is associated with potential complications. If HS lesions are not effectively excised, disease can then recur at the periphery of the excision and wound dehiscence can manifest more readily, especially as wound size increases.23 Consequently, primary closure is associated with the highest recurrence rates among closure techniques.17 Avoiding primary closure in active disease also is recommended due to the potential of burying residual foci of inflammation.6 Finally, primary closures lack skin coverage and thus often are not viable options in most perianal and genital lesions that require more extensive reconstruction. Retrospective case series and case reports exist on primary excision, but further study is needed.

Skin Grafts

Skin grafting is a technique of surgically transplanting a piece of healthy skin from one body site to another. Skin grafts typically are used when primary closure or skin flaps are not feasible (eg, in large wounds) and also when shorter time to wound closure is a greater concern in patient recovery.2,24 Additionally, skin grafts can be employed on large flat surfaces of the body, such as the buttocks or thighs, for timely wound closure when wound contraction is less effective or wound healing is slow via epithelization. Types of skin graft techniques include split-thickness skin graft (STSG), full-thickness skin graft, and recycled skin graft. All 3 types have demonstrated acceptable functional and aesthetic results in observational studies and case reports, and thus deciding which technique to use should include individualized assessment.2,25 The STSG has several advantages over the full-thickness skin graft, including hairlessness (ie, without hair follicles), ease of harvest, and a less complicated transfer to contaminated lesional areas such as those in HS.26 Additionally, STSGs allow for closure of even the largest wounds with minimal risk of serious infection. Split-thickness skin grafts are considered one of the most efficacious tools for axilla reconstruction; however, they require prolonged immobilization of the arm, result in sequelae in donor sites, and do not always prevent retractile scars.26 The recycled skin graft technique can be used to treat chronic gluteal HS, but reliability and outcomes have not been reported. Skin grafting after excision is associated with increased pain, immobilization, prolonged hospitalization, and longer healing times compared to skin flaps.19 In a systematic review of wound healing techniques following wide excision, grafting was shown to have the lowest recurrence rate (6%) compared to skin flaps (8%) and primary closure (15%).17 The absence of hair follicles and sweat glands in STSGs may be advantageous in HS because both hair follicles and sweat glands are thought to play more roles in the pathogenesis of HS.18,24 Most studies on skin grafts are limited to case reports.

Skin Flaps

Skin flaps are similar to skin grafts in that healthy skin is transplanted from one site to another; the difference is that flaps maintain an intact blood supply, whereas skin grafts depend on growth of new blood vessels.12,13 The primary advantage of skin flaps is that they provide the best quality of skin due to the thick tissue coverage, which is an important concern, especially in aesthetic scenarios. Additionally, they have been shown to provide shorter healing times than grafts, primary closure, and secondary healing, which can be especially important when functional disability is a concern in the postoperative period.26 However, their use should be limited due to several complications owing to their blood supply, as there is a high risk of ischemia to distant portions of flaps, which often can progress to necrosis and hemorrhage during the harvesting process.2 Thus, skin flaps are incredibly difficult to use in larger wounds and often require debulking due to their thickness. Additionally, skin flaps are definitive by nature, which can pose an issue if HS recurs locally. Skin flaps are recommended only when their use is mandatory, such as in the coverage of important anatomic structures (eg, exposed neurovascular bundles and large vessels).2 Advances have been made in flap construction, and now several types of flaps are employed in several body areas with differing indications and recommendations.2,21 As with skin grafts, most studies in the literature are case reports; therefore, further investigation is needed.

Combination Reconstructions

Combination reconstructions refer to the simultaneous use of multiple closure or healing techniques. By combining 2 or more methods, surgeons can utilize the advantages of each technique to provide an individualized approach that can substantially diminish wound surface area and accelerate wound healing.2 For example, with the starlike technique, 5 equilateral triangles bordering a foci of axillary disease are excised in addition to the central foci, and the edges of each triangle are then sutured together to create a final scar of considerably smaller size. The starlike technique allows the wound to be partially sutured while leaving the remaining area to heal by secondary intention.2 There are a small number of case series and prospective studies on combined reconstructions in HS but no RCTs.

Conclusion

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic inflammatory skin disease that has a social and psychosocial impact on patients with skin of color.1 It is characterized by recurrent abscesses, draining sinus tracts, and scarring in the intertriginous skin folds. The lesions are difficult to treat and present with considerable frustration for both patients and physicians. Although current treatment ladders can delay procedures and surgical intervention,1 some believe that surgery should be introduced earlier in HS management.2 In this article, we review current procedures for the management of HS, including cryoinsufflation, incision and drainage, deroofing, skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling, and wide surgical excision, along with various closure techniques.

Cryoinsufflation

First described in 2014, cryoinsufflation is a novel method for treating sinus tracts.3 Lesions initially are identified on physical examination. Prior to the procedure, local anesthesia is administered to the lesion.3 A 21-gauge needle is mounted onto a cryosurgical unit and inserted into the opening of the sinus tract. Liquid nitrogen is sprayed into the tract for 5 seconds, followed by a 3-second pause; the process is repeated 3 times. Patients return for treatment sessions monthly until the tract is obliterated. This procedure was first performed on 2 patients with satisfactory results.3

Since the initial report, the investigators made 2 changes to refine the procedure.4 First, systemic antibiotics should be prescribed 2 months prior to the procedure to clear the sinus tracts of infection. Furthermore, a 21-gauge, olive-tipped cannula is recommended in lieu of a 21-gauge needle to mitigate the risk of adverse events such as air embolism.4

Incision and Drainage

Incision and drainage provides rapid pain relief for tense fluctuant abscesses, but recurrence is common and the procedure costs are high.5 For drainage, wide circumferential local anesthesia is administered followed by incision.6 Pus is eliminated using digital pressure or saline rinses.2 Following the elimination of pus, the wound may need gauze packing or placement of a wick for a few days.6 The general belief is that incision and drainage should be used, if necessary, to rapidly relieve the patient’s pain; however, other surgical options should be considered if the patient has had multiple incision and drainage procedures.7 Currently there are no randomized controlled trials (RCTs) on incision and drainage procedures in HS abscesses.

Deroofing

In 1959, Mullins et al8 first described the deroofing procedure, which was refined to preserve the floor of the sinus tract in the 1980s.9,10 Culp10 and Brown et al9 theorized that preservation of the exposed floor of the sinus tract allowed for the epithelial cells from sweat glands and hair follicle remnants to rapidly reepithelialize the wound. In 2010, van der Zee et al11 performed a prospective study of 88 deroofed lesions in which the investigators removed keratinous debris and epithelial remnants of the floor due to concern for recurrence in this area if the tissues remained. Only 17% (15/88) of the lesions recurred at a median follow-up of 34 months.11

In Hurley stage I or II HS, deroofing remains the primary procedure for persistent nodules and sinus tracts.2 The lesion is identified on physical examination and local anesthesia is administered, first to the area surrounding the lesion, then to the lesion itself.11 A blunt probe is used to identify openings and search for connecting fistulas. After defining the sinus tract, the roof and wings created by the incision are removed.11,12 The material on the floor of the tract is scraped away, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.11 In general, deroofed lesions heal with cosmetically acceptable scars. We have used this procedure in skin of color patients with good results and no difficulties with healing. Controlled trials with long-term follow-up are lacking in this population.

Skin Tissue–Saving Excision With Electrosurgical Peeling

Skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling was first introduced in 2015.13 Blok et al14 described the procedure as a promising alternative to wide surgical excision for Hurley stage II or III HS. The procedure saves healthy tissue while completely removing lesional tissue, leading to rapid wound healing, excellent cosmesis, and a low risk of contractures2,14; however, recurrence rates are higher than those seen in wide surgical excision.15 There are no known RCTs with long-term follow-up for HS patients treated with skin tissue–saving excision with electrosurgical peeling.

The procedure typically is performed under general anesthesia.14 First, the sinus tract is palpated on physical examination and probed to delineate the extent of the tract. Next, the roof of the tract is incised electrosurgically with a wire loop tip coupled to an electrosurgical generator.14 Consecutive tangential excisions are made until the floor of the sinus tract is reached. The process of incising sinus tracts followed by tangential peeling off of tissue continues until the entire area is clear of lesional and fibrotic tissue. The wound margins are probed for the presence and subsequent removal of residual sinus tracts. Lastly, the electrosurgical generator is used to achieve hemostasis, steroids are injected to prevent the formation of hypergranulation tissue, and the wound is left to heal by secondary intention.14 Following intervention, recurrence rates appear to be similar to wide surgical excision.13,14

Wide Surgical Excision

Wide excision is a widely established technique consisting of surgical excision of a lesion plus an area of surrounding disease-free tissue such as subcutaneous fat or a lateral margin of intertriginous skin.15 Similar to other surgical techniques, wide excision is considered in cases of severe disease when pharmacologic management cannot remedy extensive fibrosis or architectural loss. It typically is performed in Hurley stage II and III HS, with pathology extending to involve deeper structures inaccessible to more superficial surgical methods.2 Prominent areas of use include gluteal, axillary, perineal, and perianal HS lesions on which conservative treatments have little effect and depend on wide excision to provide successful postoperative results.16 Although retrospective and prospective studies exist on wide excision in HS, there continues to be a dearth of RCTs. Based on the available literature, the primary motive for wide excision is lower recurrence rates (13% overall compared to 22% and 27% for local excision and deroofing, respectively) and longer asymptomatic periods compared to more local techniques.7,17 Wide excision combined with continued aggressive medical management and dietary modifications currently is an efficacious treatment in providing functional long-term results.6 These benefits, however, are not without their drawbacks, as the more extensive nature of wide surgical excision predisposes patients to larger wounds, surgery-induced infection, and prolonged recovery periods.6,15 If preoperative measurements are not wisely assessed, the excision also can extend to involve neurovascular bundles and other vital structures, contributing to greater postoperative morbidity.15 Ultrasonography provides useful anatomic information in HS, such as location and extent of fistulous tracts and fluid collections; these findings can assist in guiding the width and depth of the excision itself to ensure the entire area of HS involvement is removed.18 Published data revealed that 204 of 255 (80%) patients were markedly satisfied with postoperative outcomes of wide excision,19 which gives credence to the idea that although the complications of wide excision may not be as favorable, the long-lasting improvements in quality of life make wide surgical excision a suggested first-line treatment in all stages of HS.16,20

Closure Techniques