User login

Pediatric Hospitalists' Influences

The number of pediatric hospitalists (PH) in the United States is increasing rapidly. The membership of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine has grown to 880 (7/10, AAP Section on Hospital Medicine), and there over 10,000 members of the Society of Hospital Medicine of which an estimated 5% care for children (7/10, Society of Hospital Medicine). Little is known about the educational contributions of pediatric hospitalists, residents' perceptions of hospitalists' roles, or how hospitalists may influence residents' eventual career plans even though 89% of pediatric hospitalists report they serve as teaching attendings.1 Teaching by hospitalists is well received and valued by residents, but, to date, all such data are from single institution studies of individual hospitalist programs.27 Less is known regarding what residents perceive about the differences in patient care provided by hospitalists as compared with traditional pediatric teaching attendings. There is a paucity of information about the level of interest of current pediatric residents in becoming hospitalists, including how many plan such a career, reasons why residents might prefer to become hospitalists, and their perceptions of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) careers as either long or short term. In addition, the effects of new residency graduates going into Hospital Medicine on the overall pediatric workforce, and how the availability of Hospital Medicine careers affects the choice of practice in Primary Care Pediatrics have not been examined.

We surveyed a national, randomly selected representative sample of pediatric residents to determine their level of exposure to hospitalist attending physicians during training. We asked the resident cohort about their educational experiences with hospitalists, patient care provided by hospitalists on their team, and career plans regarding becoming a hospitalist, including perceived needs for different or additional training. We obtained further information about reasons why hospitalist positions were appealing and about the current relationship between careers in Pediatric Hospital Medicine and Primary Care. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of how pediatric hospitalists might influence residents in the domains of education, patient care, and career planning.

METHODS

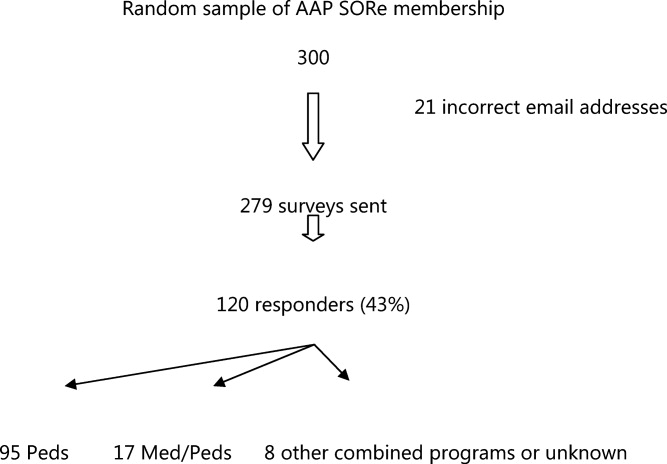

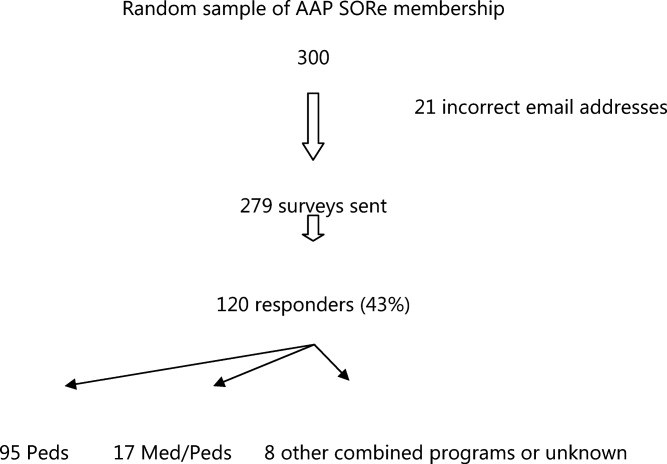

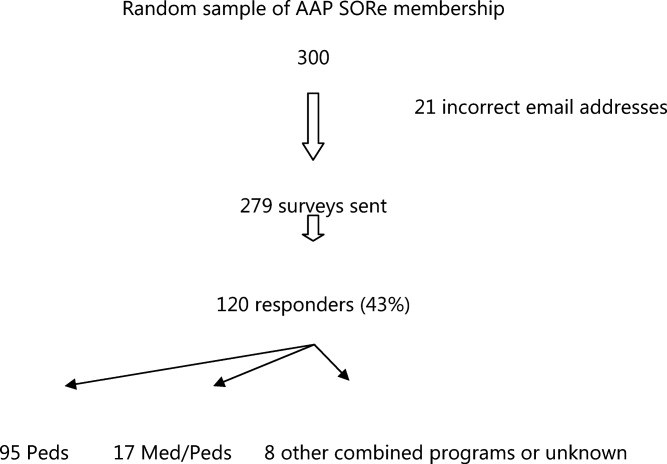

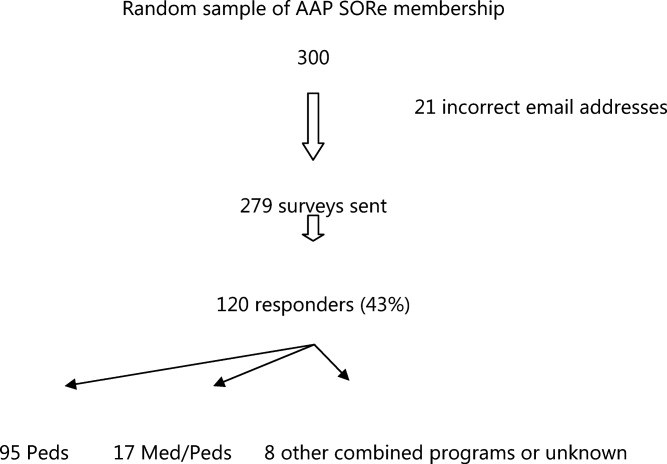

We conducted a survey of randomly selected pediatric residents from the AAP membership database. The selection was done by random generation by the AAP Department of Research from the membership database, in the same way members are selected for the annual Survey of Fellows and the annual pediatric level 3 (PL3) survey. Permission was obtained from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Residents (AAP SORe) to survey a selection of US pediatric residents in June 2007. The full sample of US pediatric residents included 9569 residents. The AAP SORe had 7694 e‐mail addresses from which the AAP Department of Research generated a random sample of 300 for our use, including Medicine‐Pediatric, Pediatric, and Pediatric Chief residents. One of the researchers (A.H.) sent an e‐mail with the title $200 AAP Career Raffle Survey containing a link to a SurveyMonkey survey (see Supporting Appendix AQuestionnaire in the online version of this article) and offering incentivized participation with a raffle. The need for informed consent was waived, as consent was implied by participation in the survey. The survey was taken anonymously by connecting through the link, and when it was completed, residents were asked to separately e‐mail a Section on Hospital Medicine address if they wished to participate in the raffle. Their raffle request was not linked to their survey results in any way. The $200 was supplied by the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine. The survey was sent 3 times. We analyzed responses with descriptive statistics. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Concord Hospital in Concord, New Hampshire.

RESULTS

The respondents are described in Figure 1 and Table 1. For their exposure to PHM, 54% (73 of 111) reported PH attendings in medical school; 90% (75 of 83) did have or will have PH attendings during residency, with no significant variation by program size (small, medium, large, or extra large). The degree of exposure was not asked. To learn about PHM, 47% (46 of 97 respondents) asked a PH in their program, while 28% (27 of 99) visited the AAP web site. Sixty‐eight percent (73 of 108) felt familiar or very familiar with PHM.

| % | Absolute Response Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Training year | ||

| PL1 | 47.5 | 57 |

| PL2 | 35 | 42 |

| PL3 | 9 | 11 |

| PL4 | 1 | 1 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31.5 | 38 |

| Female | 61 | 73 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Specialty | ||

| Pediatrics | 79 | 95 |

| Med/Peds | 14 | 17 |

| Other (Pediatric combination residencies) | 4 | 5 |

| Skipped question | 3 | 3 |

| Program size | ||

| Less than 15 residents in program | 11 | 12 |

| 16‐30 | 38.5 | 42 |

| 31‐45 | 22.9 | 25 |

| Greater than 45 | 27.5 | 30 |

| Skipped question | 9.1 | 11 |

Table 2 summarizes the respondents' perception of PHM. They report a positive opinion of the field and overwhelmingly feel that PHM is a growing/developing field. Almost none feel PHM will not survive. A small percentage (10%, 28 of 99) felt there was no difference between PH and residents, with 25% (25 of 99) feeling some ambiguity about whether the PH role differs from that of a resident. Many (35 of 99) did not disagree that there is little difference between PH and resident positions, although most did. Sixty percent (59 of 99) agreed or strongly agreed that a PH position would be a good job for the short‐term. Forty‐seven percent (46 of 99) agreed in some form that PHM gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position. Given the choice of PHM as a long‐term opportunity, short‐term opportunity, either or not sure: 21% (21 of 98) saw PHM as a short‐term option only; 26% (25 of 98) saw PHM as a long‐term career only; 49% (48 of 98) saw it as either a short‐term option or long‐term career. Most (65%, 64 of 99) believed PH were better than primary care providers at caring for complex inpatients, but only 28% (28 of 99) thought PH provided better care for routine admissions. Most (82%, 81 of 99) agreed in some form that working with pediatric hospitalists enhances a resident's education.

| Strongly/Somewhat Disagree | Neither Disagree or Agree | Somewhat/Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I think it is a great field | 2% (9/99) | 15% (15/99) | 83% (82/99) |

| It's a good job for the short‐term | 13% (13/99) | 27% (27/99) | 60% (59/99) |

| It gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position | 20% (20/99) | 33% (33/99) | 47% (46/99) |

| It's a growing/developing field | 1% (1/99) | 8% (8/99) | 91% (90/99) |

| It's a field that won't survive | 86% (85/99) | 13% (13/99) | 1% (1/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of complex inpatients than are primary care physicians | 20% (20/99) | 15% (15/99) | 65% (64/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of routine patient admissions than are primary care physicians | 39% (39/99) | 32% (32/99) | 28% (28/99) |

| There is little difference between hospitalist and resident positions | 65% (64/99) | 25% (25/99) | 10% (10/99) |

| Working with hospitalists enhances a residents education | 2% (2/99) | 16% (16/99) | 82% (81/99) |

On a 5‐point scale ranging from would definitely not include to might or might not include to would definitely include, the majority of respondents felt a PHM job would definitely include Pediatric Wards (86%, 84 of 98) and Inpatient Consultant for Specialists (54%, 52 of 97). Only 47% (46/97) felt the responsibilities would probably or definitely include Medical Student and Resident Education (47%, 46 of 97). The respondents were less certain (might or might not response) if PHM should include Normal Newborn Nursery (37%, 36 of 98), Delivery Room (42%, 41 of 98), Intensive Care Nursery (35%, 34 of 98), ED/Urgent Care (34%, 33 of 98), or Research (50%, 49 of 98). A majority of respondents felt PHM unlikely to include, or felt the job might not or might include: Outpatient Clinics (77%, 75 of 98), Outpatient Consults (81%, 79 of 98), and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit work (70%, 68 of 98).

Of categorical pediatric trainees answering the question, 35% (28 of 80) are considering a PHM career. Immediately post‐residency, 30% (24 of 80) of categorical trainees plan to enter Primary Care (PC), 4% (3 of 80) plan on PHM, and 3% (2 of 80) plan to pursue PH fellowship.

Of all respondents given the choice of whether a factor plays no role, limited role, or strong role in considering a career in PHM: flexible hours (96%, 94 of 98), opportunities to participate in education (97%, 95 of 98), and better salary than PC (94%, 91 of 97) would influence their decision to choose PHM. For 49% (48 of 98), ability to do the job without fellowship would play a strong role in choosing a career in PHM.

Forty‐five percent (44 of 97) support training in addition to residency; 16.5% (16 of 97) are against it; the remaining 38% (37 of 97) are unsure. Three percent (3 of 98) thought 3‐year fellowship best, while 28% (27 of 98) preferred 2‐year fellowship; 29% (28 of 98) would like a hospitalist‐track residency; 28% (27 of 98) believe standard residency sufficient; and 4% (4 of 98) felt a chief year adequate. If they were to pursue PHM, 31% (30 of 98) would enter PH fellowship, 34% (33 of 98) would not, and 36% (35 of 98) were unsure.

On a 5‐point scale, respondents were asked about barriers identified to choosing a career in PHM: 28% (27 of 96) agreed or strongly agreed that not feeling well‐enough trained was a barrier to entering the field; 42% (40 of 96) were agreed in some form that they were unsure of what training they needed; 39% (37 of 95) were unsure about where positions are available. Seven percent (7 of 98) of respondents were less likely to choose to practice Primary Care (PC) pediatrics because of hospitalists. Of respondents choosing PC, 59% (34 of 58) prefer or must have PH to work within their future practices, while 12% (7 of 58) prefer not to, or definitely do not want to, work with PH.

DISCUSSION

In 2006, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) General Pediatrics Career Survey found that 1% of first‐time applicants were taking a hospitalist position.8 In 2007, this number grew to 3% choosing a position in Pediatric Hospital Medicine.9, 10 The 2009‐2010 survey data found that 7.6% of first‐time applicants would be taking a job as hospitalist as of July 1.11 Our data suggest this number will continue to grow over the next few years. The growth of PHM has prompted an in‐depth look at the field by the ABP.1, 12, 13 PHM programs appear to have become part of the fabric of pediatric care, with the majority of hospitals with PHM programs planning to continue the programs despite the need to pay for value‐added by hospitalists beyond revenue received for their direct clinical service.13 Looking forward, when the Institute of Medicine recommendations to further restrict resident work hours to 16 hour shifts are implemented, many programs plan on increasing their PHM programs.14, 15 Therefore, residents' views of a career in PHM are important, as they give perspective on attitudes of those who might be, or interact with, hospitalists in the future, and should impact training programs for residents regardless of their interest in a career in PHM.

Our national data support local, large institution studies that hospitalists are positively impacting education.27 However, this study suggests that this is not only a local or large academic center phenomenon, but a national trend towards providing a different and positive education experience for pediatric residents. This mirrors the opinion of the majority of residency and clerkship directors who feel that hospitalists are more accessible to trainees than traditional attendings.12 Training programs should consider this impact when selecting attending hospitalists and supporting their roles as mentors and educators.

As residents finish their training and seek positions as pediatric hospitalists, programs need to be aware that a significant percentage of residents in our survey see PHM as a short‐term career option and/or fail to see a difference between a PH job and their own. Program Directors also need to be aware of the breadth of PHM practice which can include areas our respondents felt were less likely to be part of PHM, such as other inpatient areas and the expectation of research.

While 1 option to address some of these issues is fellowship training, this is not a simple decision. PHM needs to determine if fellowship is truly the best option for future hospitalists and, if so, what the fellowship should look like in terms of duration and scope. While the needs of optimal training should be paramount, resident preferences to not commit to an additional 3 years of training must be considered. Many residents fail to see a difference between the role of PH and their own role during training, and feel that the current format of residency training is all the preparation needed to step into a career as a PH. This demonstrates a clear gap between resident perceptions of PHM and the accepted definition of a hospitalist,16 which reaches far beyond direct inpatient care. While The Core Competencies for Pediatric Hospital Medicine17 address a number of these areas, neither trainees nor hospitalists themselves have fully integrated these into their practice. PH must recognize and prepare for their position as mentors and role models to residents. This responsibility should differentiate PH role from that of a resident, demonstrating roles PH play in policy making, patient safety and quality initiatives, in administration, and in providing advanced thinking in direct patient care. Finally, PH and their employers must work to build programs that present PHM as a long‐term career option for residents.

There is a significant impact on the field if those who enter it see it only as something to do while waiting for a position elsewhere. While some of these new‐careerists may stay with the field once they have tried it and become significant contributors, inherent in these answers are the issues of turnover and lack of senior experience many Hospital Medicine programs currently face. Additionally, and outside the scope of this survey, it is unclear what those next positions are and how a brief experience as a hospitalist might impact their future practice.

It is a significant change that residents entering a Primary Care career expect to work with pediatric hospitalists and, in general, see this as a benefit and necessity. The 2007 American Board of Pediatrics' survey found that 27% of respondents planned a career in General Pediatrics with little or no inpatient care.10 Hospitalists of the near future will likely face a dichotomy of needs between primary care providers who trained before, and those who trained after, the existence of hospitalists. Hospitalists will need to understand and address the ongoing needs of both of these groups in order to adequately serve them and their patient‐bases.

Limitations of our study include our small sample size, with a response rate of 43% at best (individual question response rate varied). Though the group was nationally representative, it was skewed towards first year respondents, likely due to the time of year in which it was distributed. There is likely some bias due to the low response rate, in that those more interested in careers as hospitalists might be more likely to respond. This might potentially inflate the percentages of those who state they are interested in being a hospitalist. In addition, given that the last round of the survey went out at the very end of the academic year, graduating residents had a lower response rate.

We were unable to compare opinions across unexposed and exposed residents because only 6.5% reported knowing nothing about the field, and only 2 respondents had not had any exposure to pediatric hospitalists to date. Given that most residencies have PHM services,12 this distinction is unlikely to be significant. In looking at training desires, we did not compare them to residents considering entering other fields of medicine. It may be true that residents considering other fellowships do not desire to do 3 years of fellowship training. That being said, it in no way diminishes the implication that 3‐year fellowships for PHM may not be the right answer for future training.

Strengths of the study include that it is, to our knowledge, the first national study of a group of residents regarding exposure to, and career plans as related to, PH. In addition, the group is gender‐balanced, and represents residents from a range of training sites (urban, suburban, rural) and program sizes. This study offers important information that must be considered in the further development of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

CONCLUSION

This was the first national study of residents regarding Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Almost all residents are exposed to PH during their training, though a gap of no exposure still exists. More work needs to be done to improve the perception of PHM as a viable long‐term career. Nevertheless, PHM has become a career consideration for trainees. Nearly half agreed that some type of specialized training would be helpful. This information should impact on the development of PHM training programs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine for raffle funding, and Texas Children's Hospital and Dr Yong Han for use of SurveyMonkey and assistance with survey set‐up. Also thanks to Dr Vincent Chang for his guidance and review.

- ,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment.Pediatrics.2007;120(1):33–39.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156(9):877–883.

- ,,.Establishing a pediatric hospitalist program at an academic medical center.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2000;39(4):221–227.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2001;40(12):653–660.

- .Employing hospitalists to improve residents' inpatient learning.Acad Med.2001;76(5):556.

- ,,,,,.Community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):34–38.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2006 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed on January 15, 2008.

- ,,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.General pediatrics resident perspectives on training decisions and career choice.Pediatrics.2009;123(1 suppl):S26–S30.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2007 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 10,2009.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2009–2010 Workforce Data. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 20,2010.

- ,,.Hospitalists' involvement in pediatrics training: perspectives from pediatric residency program and clerkship directors.Acad Med.2009;84(11):1617–1621.

- ,,.Assessing the value of pediatric hospitalist programs: the perspective of hospital leaders.Acad Pediatr.2009;9(3):192–196.

- ,,,.Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist.J Hosp Med.2011;6(in press).

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/. Accessed December 15, 2010.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Hospitalist_Definition5:i–iv. doi://10.1002/jhm.776. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed on May 11, 2011.

The number of pediatric hospitalists (PH) in the United States is increasing rapidly. The membership of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine has grown to 880 (7/10, AAP Section on Hospital Medicine), and there over 10,000 members of the Society of Hospital Medicine of which an estimated 5% care for children (7/10, Society of Hospital Medicine). Little is known about the educational contributions of pediatric hospitalists, residents' perceptions of hospitalists' roles, or how hospitalists may influence residents' eventual career plans even though 89% of pediatric hospitalists report they serve as teaching attendings.1 Teaching by hospitalists is well received and valued by residents, but, to date, all such data are from single institution studies of individual hospitalist programs.27 Less is known regarding what residents perceive about the differences in patient care provided by hospitalists as compared with traditional pediatric teaching attendings. There is a paucity of information about the level of interest of current pediatric residents in becoming hospitalists, including how many plan such a career, reasons why residents might prefer to become hospitalists, and their perceptions of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) careers as either long or short term. In addition, the effects of new residency graduates going into Hospital Medicine on the overall pediatric workforce, and how the availability of Hospital Medicine careers affects the choice of practice in Primary Care Pediatrics have not been examined.

We surveyed a national, randomly selected representative sample of pediatric residents to determine their level of exposure to hospitalist attending physicians during training. We asked the resident cohort about their educational experiences with hospitalists, patient care provided by hospitalists on their team, and career plans regarding becoming a hospitalist, including perceived needs for different or additional training. We obtained further information about reasons why hospitalist positions were appealing and about the current relationship between careers in Pediatric Hospital Medicine and Primary Care. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of how pediatric hospitalists might influence residents in the domains of education, patient care, and career planning.

METHODS

We conducted a survey of randomly selected pediatric residents from the AAP membership database. The selection was done by random generation by the AAP Department of Research from the membership database, in the same way members are selected for the annual Survey of Fellows and the annual pediatric level 3 (PL3) survey. Permission was obtained from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Residents (AAP SORe) to survey a selection of US pediatric residents in June 2007. The full sample of US pediatric residents included 9569 residents. The AAP SORe had 7694 e‐mail addresses from which the AAP Department of Research generated a random sample of 300 for our use, including Medicine‐Pediatric, Pediatric, and Pediatric Chief residents. One of the researchers (A.H.) sent an e‐mail with the title $200 AAP Career Raffle Survey containing a link to a SurveyMonkey survey (see Supporting Appendix AQuestionnaire in the online version of this article) and offering incentivized participation with a raffle. The need for informed consent was waived, as consent was implied by participation in the survey. The survey was taken anonymously by connecting through the link, and when it was completed, residents were asked to separately e‐mail a Section on Hospital Medicine address if they wished to participate in the raffle. Their raffle request was not linked to their survey results in any way. The $200 was supplied by the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine. The survey was sent 3 times. We analyzed responses with descriptive statistics. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Concord Hospital in Concord, New Hampshire.

RESULTS

The respondents are described in Figure 1 and Table 1. For their exposure to PHM, 54% (73 of 111) reported PH attendings in medical school; 90% (75 of 83) did have or will have PH attendings during residency, with no significant variation by program size (small, medium, large, or extra large). The degree of exposure was not asked. To learn about PHM, 47% (46 of 97 respondents) asked a PH in their program, while 28% (27 of 99) visited the AAP web site. Sixty‐eight percent (73 of 108) felt familiar or very familiar with PHM.

| % | Absolute Response Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Training year | ||

| PL1 | 47.5 | 57 |

| PL2 | 35 | 42 |

| PL3 | 9 | 11 |

| PL4 | 1 | 1 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31.5 | 38 |

| Female | 61 | 73 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Specialty | ||

| Pediatrics | 79 | 95 |

| Med/Peds | 14 | 17 |

| Other (Pediatric combination residencies) | 4 | 5 |

| Skipped question | 3 | 3 |

| Program size | ||

| Less than 15 residents in program | 11 | 12 |

| 16‐30 | 38.5 | 42 |

| 31‐45 | 22.9 | 25 |

| Greater than 45 | 27.5 | 30 |

| Skipped question | 9.1 | 11 |

Table 2 summarizes the respondents' perception of PHM. They report a positive opinion of the field and overwhelmingly feel that PHM is a growing/developing field. Almost none feel PHM will not survive. A small percentage (10%, 28 of 99) felt there was no difference between PH and residents, with 25% (25 of 99) feeling some ambiguity about whether the PH role differs from that of a resident. Many (35 of 99) did not disagree that there is little difference between PH and resident positions, although most did. Sixty percent (59 of 99) agreed or strongly agreed that a PH position would be a good job for the short‐term. Forty‐seven percent (46 of 99) agreed in some form that PHM gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position. Given the choice of PHM as a long‐term opportunity, short‐term opportunity, either or not sure: 21% (21 of 98) saw PHM as a short‐term option only; 26% (25 of 98) saw PHM as a long‐term career only; 49% (48 of 98) saw it as either a short‐term option or long‐term career. Most (65%, 64 of 99) believed PH were better than primary care providers at caring for complex inpatients, but only 28% (28 of 99) thought PH provided better care for routine admissions. Most (82%, 81 of 99) agreed in some form that working with pediatric hospitalists enhances a resident's education.

| Strongly/Somewhat Disagree | Neither Disagree or Agree | Somewhat/Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I think it is a great field | 2% (9/99) | 15% (15/99) | 83% (82/99) |

| It's a good job for the short‐term | 13% (13/99) | 27% (27/99) | 60% (59/99) |

| It gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position | 20% (20/99) | 33% (33/99) | 47% (46/99) |

| It's a growing/developing field | 1% (1/99) | 8% (8/99) | 91% (90/99) |

| It's a field that won't survive | 86% (85/99) | 13% (13/99) | 1% (1/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of complex inpatients than are primary care physicians | 20% (20/99) | 15% (15/99) | 65% (64/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of routine patient admissions than are primary care physicians | 39% (39/99) | 32% (32/99) | 28% (28/99) |

| There is little difference between hospitalist and resident positions | 65% (64/99) | 25% (25/99) | 10% (10/99) |

| Working with hospitalists enhances a residents education | 2% (2/99) | 16% (16/99) | 82% (81/99) |

On a 5‐point scale ranging from would definitely not include to might or might not include to would definitely include, the majority of respondents felt a PHM job would definitely include Pediatric Wards (86%, 84 of 98) and Inpatient Consultant for Specialists (54%, 52 of 97). Only 47% (46/97) felt the responsibilities would probably or definitely include Medical Student and Resident Education (47%, 46 of 97). The respondents were less certain (might or might not response) if PHM should include Normal Newborn Nursery (37%, 36 of 98), Delivery Room (42%, 41 of 98), Intensive Care Nursery (35%, 34 of 98), ED/Urgent Care (34%, 33 of 98), or Research (50%, 49 of 98). A majority of respondents felt PHM unlikely to include, or felt the job might not or might include: Outpatient Clinics (77%, 75 of 98), Outpatient Consults (81%, 79 of 98), and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit work (70%, 68 of 98).

Of categorical pediatric trainees answering the question, 35% (28 of 80) are considering a PHM career. Immediately post‐residency, 30% (24 of 80) of categorical trainees plan to enter Primary Care (PC), 4% (3 of 80) plan on PHM, and 3% (2 of 80) plan to pursue PH fellowship.

Of all respondents given the choice of whether a factor plays no role, limited role, or strong role in considering a career in PHM: flexible hours (96%, 94 of 98), opportunities to participate in education (97%, 95 of 98), and better salary than PC (94%, 91 of 97) would influence their decision to choose PHM. For 49% (48 of 98), ability to do the job without fellowship would play a strong role in choosing a career in PHM.

Forty‐five percent (44 of 97) support training in addition to residency; 16.5% (16 of 97) are against it; the remaining 38% (37 of 97) are unsure. Three percent (3 of 98) thought 3‐year fellowship best, while 28% (27 of 98) preferred 2‐year fellowship; 29% (28 of 98) would like a hospitalist‐track residency; 28% (27 of 98) believe standard residency sufficient; and 4% (4 of 98) felt a chief year adequate. If they were to pursue PHM, 31% (30 of 98) would enter PH fellowship, 34% (33 of 98) would not, and 36% (35 of 98) were unsure.

On a 5‐point scale, respondents were asked about barriers identified to choosing a career in PHM: 28% (27 of 96) agreed or strongly agreed that not feeling well‐enough trained was a barrier to entering the field; 42% (40 of 96) were agreed in some form that they were unsure of what training they needed; 39% (37 of 95) were unsure about where positions are available. Seven percent (7 of 98) of respondents were less likely to choose to practice Primary Care (PC) pediatrics because of hospitalists. Of respondents choosing PC, 59% (34 of 58) prefer or must have PH to work within their future practices, while 12% (7 of 58) prefer not to, or definitely do not want to, work with PH.

DISCUSSION

In 2006, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) General Pediatrics Career Survey found that 1% of first‐time applicants were taking a hospitalist position.8 In 2007, this number grew to 3% choosing a position in Pediatric Hospital Medicine.9, 10 The 2009‐2010 survey data found that 7.6% of first‐time applicants would be taking a job as hospitalist as of July 1.11 Our data suggest this number will continue to grow over the next few years. The growth of PHM has prompted an in‐depth look at the field by the ABP.1, 12, 13 PHM programs appear to have become part of the fabric of pediatric care, with the majority of hospitals with PHM programs planning to continue the programs despite the need to pay for value‐added by hospitalists beyond revenue received for their direct clinical service.13 Looking forward, when the Institute of Medicine recommendations to further restrict resident work hours to 16 hour shifts are implemented, many programs plan on increasing their PHM programs.14, 15 Therefore, residents' views of a career in PHM are important, as they give perspective on attitudes of those who might be, or interact with, hospitalists in the future, and should impact training programs for residents regardless of their interest in a career in PHM.

Our national data support local, large institution studies that hospitalists are positively impacting education.27 However, this study suggests that this is not only a local or large academic center phenomenon, but a national trend towards providing a different and positive education experience for pediatric residents. This mirrors the opinion of the majority of residency and clerkship directors who feel that hospitalists are more accessible to trainees than traditional attendings.12 Training programs should consider this impact when selecting attending hospitalists and supporting their roles as mentors and educators.

As residents finish their training and seek positions as pediatric hospitalists, programs need to be aware that a significant percentage of residents in our survey see PHM as a short‐term career option and/or fail to see a difference between a PH job and their own. Program Directors also need to be aware of the breadth of PHM practice which can include areas our respondents felt were less likely to be part of PHM, such as other inpatient areas and the expectation of research.

While 1 option to address some of these issues is fellowship training, this is not a simple decision. PHM needs to determine if fellowship is truly the best option for future hospitalists and, if so, what the fellowship should look like in terms of duration and scope. While the needs of optimal training should be paramount, resident preferences to not commit to an additional 3 years of training must be considered. Many residents fail to see a difference between the role of PH and their own role during training, and feel that the current format of residency training is all the preparation needed to step into a career as a PH. This demonstrates a clear gap between resident perceptions of PHM and the accepted definition of a hospitalist,16 which reaches far beyond direct inpatient care. While The Core Competencies for Pediatric Hospital Medicine17 address a number of these areas, neither trainees nor hospitalists themselves have fully integrated these into their practice. PH must recognize and prepare for their position as mentors and role models to residents. This responsibility should differentiate PH role from that of a resident, demonstrating roles PH play in policy making, patient safety and quality initiatives, in administration, and in providing advanced thinking in direct patient care. Finally, PH and their employers must work to build programs that present PHM as a long‐term career option for residents.

There is a significant impact on the field if those who enter it see it only as something to do while waiting for a position elsewhere. While some of these new‐careerists may stay with the field once they have tried it and become significant contributors, inherent in these answers are the issues of turnover and lack of senior experience many Hospital Medicine programs currently face. Additionally, and outside the scope of this survey, it is unclear what those next positions are and how a brief experience as a hospitalist might impact their future practice.

It is a significant change that residents entering a Primary Care career expect to work with pediatric hospitalists and, in general, see this as a benefit and necessity. The 2007 American Board of Pediatrics' survey found that 27% of respondents planned a career in General Pediatrics with little or no inpatient care.10 Hospitalists of the near future will likely face a dichotomy of needs between primary care providers who trained before, and those who trained after, the existence of hospitalists. Hospitalists will need to understand and address the ongoing needs of both of these groups in order to adequately serve them and their patient‐bases.

Limitations of our study include our small sample size, with a response rate of 43% at best (individual question response rate varied). Though the group was nationally representative, it was skewed towards first year respondents, likely due to the time of year in which it was distributed. There is likely some bias due to the low response rate, in that those more interested in careers as hospitalists might be more likely to respond. This might potentially inflate the percentages of those who state they are interested in being a hospitalist. In addition, given that the last round of the survey went out at the very end of the academic year, graduating residents had a lower response rate.

We were unable to compare opinions across unexposed and exposed residents because only 6.5% reported knowing nothing about the field, and only 2 respondents had not had any exposure to pediatric hospitalists to date. Given that most residencies have PHM services,12 this distinction is unlikely to be significant. In looking at training desires, we did not compare them to residents considering entering other fields of medicine. It may be true that residents considering other fellowships do not desire to do 3 years of fellowship training. That being said, it in no way diminishes the implication that 3‐year fellowships for PHM may not be the right answer for future training.

Strengths of the study include that it is, to our knowledge, the first national study of a group of residents regarding exposure to, and career plans as related to, PH. In addition, the group is gender‐balanced, and represents residents from a range of training sites (urban, suburban, rural) and program sizes. This study offers important information that must be considered in the further development of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

CONCLUSION

This was the first national study of residents regarding Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Almost all residents are exposed to PH during their training, though a gap of no exposure still exists. More work needs to be done to improve the perception of PHM as a viable long‐term career. Nevertheless, PHM has become a career consideration for trainees. Nearly half agreed that some type of specialized training would be helpful. This information should impact on the development of PHM training programs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine for raffle funding, and Texas Children's Hospital and Dr Yong Han for use of SurveyMonkey and assistance with survey set‐up. Also thanks to Dr Vincent Chang for his guidance and review.

The number of pediatric hospitalists (PH) in the United States is increasing rapidly. The membership of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) Section on Hospital Medicine has grown to 880 (7/10, AAP Section on Hospital Medicine), and there over 10,000 members of the Society of Hospital Medicine of which an estimated 5% care for children (7/10, Society of Hospital Medicine). Little is known about the educational contributions of pediatric hospitalists, residents' perceptions of hospitalists' roles, or how hospitalists may influence residents' eventual career plans even though 89% of pediatric hospitalists report they serve as teaching attendings.1 Teaching by hospitalists is well received and valued by residents, but, to date, all such data are from single institution studies of individual hospitalist programs.27 Less is known regarding what residents perceive about the differences in patient care provided by hospitalists as compared with traditional pediatric teaching attendings. There is a paucity of information about the level of interest of current pediatric residents in becoming hospitalists, including how many plan such a career, reasons why residents might prefer to become hospitalists, and their perceptions of Pediatric Hospital Medicine (PHM) careers as either long or short term. In addition, the effects of new residency graduates going into Hospital Medicine on the overall pediatric workforce, and how the availability of Hospital Medicine careers affects the choice of practice in Primary Care Pediatrics have not been examined.

We surveyed a national, randomly selected representative sample of pediatric residents to determine their level of exposure to hospitalist attending physicians during training. We asked the resident cohort about their educational experiences with hospitalists, patient care provided by hospitalists on their team, and career plans regarding becoming a hospitalist, including perceived needs for different or additional training. We obtained further information about reasons why hospitalist positions were appealing and about the current relationship between careers in Pediatric Hospital Medicine and Primary Care. To our knowledge, this is the first national study of how pediatric hospitalists might influence residents in the domains of education, patient care, and career planning.

METHODS

We conducted a survey of randomly selected pediatric residents from the AAP membership database. The selection was done by random generation by the AAP Department of Research from the membership database, in the same way members are selected for the annual Survey of Fellows and the annual pediatric level 3 (PL3) survey. Permission was obtained from the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Residents (AAP SORe) to survey a selection of US pediatric residents in June 2007. The full sample of US pediatric residents included 9569 residents. The AAP SORe had 7694 e‐mail addresses from which the AAP Department of Research generated a random sample of 300 for our use, including Medicine‐Pediatric, Pediatric, and Pediatric Chief residents. One of the researchers (A.H.) sent an e‐mail with the title $200 AAP Career Raffle Survey containing a link to a SurveyMonkey survey (see Supporting Appendix AQuestionnaire in the online version of this article) and offering incentivized participation with a raffle. The need for informed consent was waived, as consent was implied by participation in the survey. The survey was taken anonymously by connecting through the link, and when it was completed, residents were asked to separately e‐mail a Section on Hospital Medicine address if they wished to participate in the raffle. Their raffle request was not linked to their survey results in any way. The $200 was supplied by the AAP Section on Hospital Medicine. The survey was sent 3 times. We analyzed responses with descriptive statistics. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from Concord Hospital in Concord, New Hampshire.

RESULTS

The respondents are described in Figure 1 and Table 1. For their exposure to PHM, 54% (73 of 111) reported PH attendings in medical school; 90% (75 of 83) did have or will have PH attendings during residency, with no significant variation by program size (small, medium, large, or extra large). The degree of exposure was not asked. To learn about PHM, 47% (46 of 97 respondents) asked a PH in their program, while 28% (27 of 99) visited the AAP web site. Sixty‐eight percent (73 of 108) felt familiar or very familiar with PHM.

| % | Absolute Response Rate | |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Training year | ||

| PL1 | 47.5 | 57 |

| PL2 | 35 | 42 |

| PL3 | 9 | 11 |

| PL4 | 1 | 1 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 31.5 | 38 |

| Female | 61 | 73 |

| Skipped question | 7.5 | 9 |

| Specialty | ||

| Pediatrics | 79 | 95 |

| Med/Peds | 14 | 17 |

| Other (Pediatric combination residencies) | 4 | 5 |

| Skipped question | 3 | 3 |

| Program size | ||

| Less than 15 residents in program | 11 | 12 |

| 16‐30 | 38.5 | 42 |

| 31‐45 | 22.9 | 25 |

| Greater than 45 | 27.5 | 30 |

| Skipped question | 9.1 | 11 |

Table 2 summarizes the respondents' perception of PHM. They report a positive opinion of the field and overwhelmingly feel that PHM is a growing/developing field. Almost none feel PHM will not survive. A small percentage (10%, 28 of 99) felt there was no difference between PH and residents, with 25% (25 of 99) feeling some ambiguity about whether the PH role differs from that of a resident. Many (35 of 99) did not disagree that there is little difference between PH and resident positions, although most did. Sixty percent (59 of 99) agreed or strongly agreed that a PH position would be a good job for the short‐term. Forty‐seven percent (46 of 99) agreed in some form that PHM gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position. Given the choice of PHM as a long‐term opportunity, short‐term opportunity, either or not sure: 21% (21 of 98) saw PHM as a short‐term option only; 26% (25 of 98) saw PHM as a long‐term career only; 49% (48 of 98) saw it as either a short‐term option or long‐term career. Most (65%, 64 of 99) believed PH were better than primary care providers at caring for complex inpatients, but only 28% (28 of 99) thought PH provided better care for routine admissions. Most (82%, 81 of 99) agreed in some form that working with pediatric hospitalists enhances a resident's education.

| Strongly/Somewhat Disagree | Neither Disagree or Agree | Somewhat/Strongly Agree | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| I think it is a great field | 2% (9/99) | 15% (15/99) | 83% (82/99) |

| It's a good job for the short‐term | 13% (13/99) | 27% (27/99) | 60% (59/99) |

| It gives you something to do while you are waiting for another position | 20% (20/99) | 33% (33/99) | 47% (46/99) |

| It's a growing/developing field | 1% (1/99) | 8% (8/99) | 91% (90/99) |

| It's a field that won't survive | 86% (85/99) | 13% (13/99) | 1% (1/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of complex inpatients than are primary care physicians | 20% (20/99) | 15% (15/99) | 65% (64/99) |

| Hospitalists are better able to take care of routine patient admissions than are primary care physicians | 39% (39/99) | 32% (32/99) | 28% (28/99) |

| There is little difference between hospitalist and resident positions | 65% (64/99) | 25% (25/99) | 10% (10/99) |

| Working with hospitalists enhances a residents education | 2% (2/99) | 16% (16/99) | 82% (81/99) |

On a 5‐point scale ranging from would definitely not include to might or might not include to would definitely include, the majority of respondents felt a PHM job would definitely include Pediatric Wards (86%, 84 of 98) and Inpatient Consultant for Specialists (54%, 52 of 97). Only 47% (46/97) felt the responsibilities would probably or definitely include Medical Student and Resident Education (47%, 46 of 97). The respondents were less certain (might or might not response) if PHM should include Normal Newborn Nursery (37%, 36 of 98), Delivery Room (42%, 41 of 98), Intensive Care Nursery (35%, 34 of 98), ED/Urgent Care (34%, 33 of 98), or Research (50%, 49 of 98). A majority of respondents felt PHM unlikely to include, or felt the job might not or might include: Outpatient Clinics (77%, 75 of 98), Outpatient Consults (81%, 79 of 98), and Pediatric Intensive Care Unit work (70%, 68 of 98).

Of categorical pediatric trainees answering the question, 35% (28 of 80) are considering a PHM career. Immediately post‐residency, 30% (24 of 80) of categorical trainees plan to enter Primary Care (PC), 4% (3 of 80) plan on PHM, and 3% (2 of 80) plan to pursue PH fellowship.

Of all respondents given the choice of whether a factor plays no role, limited role, or strong role in considering a career in PHM: flexible hours (96%, 94 of 98), opportunities to participate in education (97%, 95 of 98), and better salary than PC (94%, 91 of 97) would influence their decision to choose PHM. For 49% (48 of 98), ability to do the job without fellowship would play a strong role in choosing a career in PHM.

Forty‐five percent (44 of 97) support training in addition to residency; 16.5% (16 of 97) are against it; the remaining 38% (37 of 97) are unsure. Three percent (3 of 98) thought 3‐year fellowship best, while 28% (27 of 98) preferred 2‐year fellowship; 29% (28 of 98) would like a hospitalist‐track residency; 28% (27 of 98) believe standard residency sufficient; and 4% (4 of 98) felt a chief year adequate. If they were to pursue PHM, 31% (30 of 98) would enter PH fellowship, 34% (33 of 98) would not, and 36% (35 of 98) were unsure.

On a 5‐point scale, respondents were asked about barriers identified to choosing a career in PHM: 28% (27 of 96) agreed or strongly agreed that not feeling well‐enough trained was a barrier to entering the field; 42% (40 of 96) were agreed in some form that they were unsure of what training they needed; 39% (37 of 95) were unsure about where positions are available. Seven percent (7 of 98) of respondents were less likely to choose to practice Primary Care (PC) pediatrics because of hospitalists. Of respondents choosing PC, 59% (34 of 58) prefer or must have PH to work within their future practices, while 12% (7 of 58) prefer not to, or definitely do not want to, work with PH.

DISCUSSION

In 2006, the American Board of Pediatrics (ABP) General Pediatrics Career Survey found that 1% of first‐time applicants were taking a hospitalist position.8 In 2007, this number grew to 3% choosing a position in Pediatric Hospital Medicine.9, 10 The 2009‐2010 survey data found that 7.6% of first‐time applicants would be taking a job as hospitalist as of July 1.11 Our data suggest this number will continue to grow over the next few years. The growth of PHM has prompted an in‐depth look at the field by the ABP.1, 12, 13 PHM programs appear to have become part of the fabric of pediatric care, with the majority of hospitals with PHM programs planning to continue the programs despite the need to pay for value‐added by hospitalists beyond revenue received for their direct clinical service.13 Looking forward, when the Institute of Medicine recommendations to further restrict resident work hours to 16 hour shifts are implemented, many programs plan on increasing their PHM programs.14, 15 Therefore, residents' views of a career in PHM are important, as they give perspective on attitudes of those who might be, or interact with, hospitalists in the future, and should impact training programs for residents regardless of their interest in a career in PHM.

Our national data support local, large institution studies that hospitalists are positively impacting education.27 However, this study suggests that this is not only a local or large academic center phenomenon, but a national trend towards providing a different and positive education experience for pediatric residents. This mirrors the opinion of the majority of residency and clerkship directors who feel that hospitalists are more accessible to trainees than traditional attendings.12 Training programs should consider this impact when selecting attending hospitalists and supporting their roles as mentors and educators.

As residents finish their training and seek positions as pediatric hospitalists, programs need to be aware that a significant percentage of residents in our survey see PHM as a short‐term career option and/or fail to see a difference between a PH job and their own. Program Directors also need to be aware of the breadth of PHM practice which can include areas our respondents felt were less likely to be part of PHM, such as other inpatient areas and the expectation of research.

While 1 option to address some of these issues is fellowship training, this is not a simple decision. PHM needs to determine if fellowship is truly the best option for future hospitalists and, if so, what the fellowship should look like in terms of duration and scope. While the needs of optimal training should be paramount, resident preferences to not commit to an additional 3 years of training must be considered. Many residents fail to see a difference between the role of PH and their own role during training, and feel that the current format of residency training is all the preparation needed to step into a career as a PH. This demonstrates a clear gap between resident perceptions of PHM and the accepted definition of a hospitalist,16 which reaches far beyond direct inpatient care. While The Core Competencies for Pediatric Hospital Medicine17 address a number of these areas, neither trainees nor hospitalists themselves have fully integrated these into their practice. PH must recognize and prepare for their position as mentors and role models to residents. This responsibility should differentiate PH role from that of a resident, demonstrating roles PH play in policy making, patient safety and quality initiatives, in administration, and in providing advanced thinking in direct patient care. Finally, PH and their employers must work to build programs that present PHM as a long‐term career option for residents.

There is a significant impact on the field if those who enter it see it only as something to do while waiting for a position elsewhere. While some of these new‐careerists may stay with the field once they have tried it and become significant contributors, inherent in these answers are the issues of turnover and lack of senior experience many Hospital Medicine programs currently face. Additionally, and outside the scope of this survey, it is unclear what those next positions are and how a brief experience as a hospitalist might impact their future practice.

It is a significant change that residents entering a Primary Care career expect to work with pediatric hospitalists and, in general, see this as a benefit and necessity. The 2007 American Board of Pediatrics' survey found that 27% of respondents planned a career in General Pediatrics with little or no inpatient care.10 Hospitalists of the near future will likely face a dichotomy of needs between primary care providers who trained before, and those who trained after, the existence of hospitalists. Hospitalists will need to understand and address the ongoing needs of both of these groups in order to adequately serve them and their patient‐bases.

Limitations of our study include our small sample size, with a response rate of 43% at best (individual question response rate varied). Though the group was nationally representative, it was skewed towards first year respondents, likely due to the time of year in which it was distributed. There is likely some bias due to the low response rate, in that those more interested in careers as hospitalists might be more likely to respond. This might potentially inflate the percentages of those who state they are interested in being a hospitalist. In addition, given that the last round of the survey went out at the very end of the academic year, graduating residents had a lower response rate.

We were unable to compare opinions across unexposed and exposed residents because only 6.5% reported knowing nothing about the field, and only 2 respondents had not had any exposure to pediatric hospitalists to date. Given that most residencies have PHM services,12 this distinction is unlikely to be significant. In looking at training desires, we did not compare them to residents considering entering other fields of medicine. It may be true that residents considering other fellowships do not desire to do 3 years of fellowship training. That being said, it in no way diminishes the implication that 3‐year fellowships for PHM may not be the right answer for future training.

Strengths of the study include that it is, to our knowledge, the first national study of a group of residents regarding exposure to, and career plans as related to, PH. In addition, the group is gender‐balanced, and represents residents from a range of training sites (urban, suburban, rural) and program sizes. This study offers important information that must be considered in the further development of the field of Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

CONCLUSION

This was the first national study of residents regarding Pediatric Hospital Medicine. Almost all residents are exposed to PH during their training, though a gap of no exposure still exists. More work needs to be done to improve the perception of PHM as a viable long‐term career. Nevertheless, PHM has become a career consideration for trainees. Nearly half agreed that some type of specialized training would be helpful. This information should impact on the development of PHM training programs.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine for raffle funding, and Texas Children's Hospital and Dr Yong Han for use of SurveyMonkey and assistance with survey set‐up. Also thanks to Dr Vincent Chang for his guidance and review.

- ,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment.Pediatrics.2007;120(1):33–39.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156(9):877–883.

- ,,.Establishing a pediatric hospitalist program at an academic medical center.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2000;39(4):221–227.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2001;40(12):653–660.

- .Employing hospitalists to improve residents' inpatient learning.Acad Med.2001;76(5):556.

- ,,,,,.Community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):34–38.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2006 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed on January 15, 2008.

- ,,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.General pediatrics resident perspectives on training decisions and career choice.Pediatrics.2009;123(1 suppl):S26–S30.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2007 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 10,2009.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2009–2010 Workforce Data. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 20,2010.

- ,,.Hospitalists' involvement in pediatrics training: perspectives from pediatric residency program and clerkship directors.Acad Med.2009;84(11):1617–1621.

- ,,.Assessing the value of pediatric hospitalist programs: the perspective of hospital leaders.Acad Pediatr.2009;9(3):192–196.

- ,,,.Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist.J Hosp Med.2011;6(in press).

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/. Accessed December 15, 2010.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Hospitalist_Definition5:i–iv. doi://10.1002/jhm.776. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed on May 11, 2011.

- ,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.Characteristics of the pediatric hospitalist workforce: its roles and work environment.Pediatrics.2007;120(1):33–39.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a pediatric hospitalist system on housestaff education and experience.Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med.2002;156(9):877–883.

- ,,.Establishing a pediatric hospitalist program at an academic medical center.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2000;39(4):221–227.

- ,,,,,.Restructuring an academic pediatric inpatient service using concepts developed by hospitalists.Clin Pediatr (Phila).2001;40(12):653–660.

- .Employing hospitalists to improve residents' inpatient learning.Acad Med.2001;76(5):556.

- ,,,,,.Community and hospital‐based physicians' attitudes regarding pediatric hospitalist systems.Pediatrics.2005;115(1):34–38.

- ,,,.Pediatric hospitalists: a systematic review of the literature.Pediatrics.2006;117(5):1736–1744.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2006 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed on January 15, 2008.

- ,,,,;for the Research Advisory Committee of the American Board of Pediatrics.General pediatrics resident perspectives on training decisions and career choice.Pediatrics.2009;123(1 suppl):S26–S30.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2007 General Pediatrics Career Survey. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 10,2009.

- American Board of Pediatrics. 2009–2010 Workforce Data. Available at: http://www.abp.org. Accessed July 20,2010.

- ,,.Hospitalists' involvement in pediatrics training: perspectives from pediatric residency program and clerkship directors.Acad Med.2009;84(11):1617–1621.

- ,,.Assessing the value of pediatric hospitalist programs: the perspective of hospital leaders.Acad Pediatr.2009;9(3):192–196.

- ,,,.Inpatient staffing within pediatric residency programs: work hour restrictions and the evolving role of the pediatric hospitalist.J Hosp Med.2011;6(in press).

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Available at: http://acgme‐2010standards.org/. Accessed December 15, 2010.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Hospitalist_Definition5:i–iv. doi://10.1002/jhm.776. Available at: http://www3.interscience.wiley.com. Accessed on May 11, 2011.

Copyright © 2011 Society of Hospital Medicine