User login

Papular Rash in a New Tattoo

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

The Diagnosis: Allergic Contact Dermatitis

This patient’s history and physical examination were most consistent with a diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, likely from an additive or diluent solution within the tattoo ink. Her history of a similar transient reaction following tattooing 2 weeks prior lent credence to an allergic etiology. She was treated with triamcinolone cream 0.1% as well as mupirocin ointment 2% for use as both an emollient and for precautionary antimicrobial coverage. The rash resolved within 2 days, and she reported no recurrence at a 6-month follow-up. The cosmesis of her tattoo was preserved.

Acute cellulitis may follow tattooing, but the absence of warmth, pain, or purulence on physical examination made this diagnosis less likely in this patient. Sarcoidosis or other granulomatous reactions may present as papules or nodules arising within a tattoo but would be unlikely to occur the next day. Nontuberculous mycobacterial infection likewise tends to present subacutely or chronically rather than immediately following tattoo application.

Tattooing has existed for millennia and is becoming increasingly popular.1,2 The tattooing process entails introduction of insoluble pigment compounds into the dermis to create a permanent design on the skin, which most often is accomplished via needling. As a result, tattooed skin is susceptible to both acute and chronic complications. Acute complications prominently include allergic hypersensitivity reactions and pyogenic bacterial infections. Chronic granulomatous, inflammatory, or infectious complications also can occur.

Allergic eczematous reactions to tattooing are well documented in the literature and are thought to originate from sensitization to pigment molecules themselves or alternatively to ink diluent compounds.3 Although reactions to ink diluent chemicals typically are self-resolving, allergic reactions to pigment can persist beyond the acute phase, as these insoluble compounds intentionally remain embedded in the dermis. The mechanism of action may involve haptenization of pigment molecules that then induces allergic hypersensitivity.3,4 Black pigment typically is derived from carbon black (ie, amorphous combustion byproducts such as soot). Colored inks historically consisted of inorganic heavy metal–containing salts prior to the modern introduction of synthetic azo and polycyclic dyes. These newer colored pigments appear to be less allergenic than their metallic predecessors; however, epidemiologic studies have suggested that allergic reactions still occur more commonly in colored tattoos than black tattoos.1 Overall, these reactions may occur in as many as one-third of individuals who receive tattoos.2,4

As with any process that disrupts skin integrity, tattooing carries a risk for transmitting various infectious pathogens. Microbes may originate from adjacent skin, contaminated needles, ink bottles, or nonsterile ink diluents. Although tattoo parlors and artists may undergo licensing to demonstrate adherence to hygienic standards, regulations vary between states and do not include testing of ink or ink additives to ensure sterility.4,5 Staphylococci and streptococci commonly are implicated in acute pyogenic skin infections following tattooing.5,6 Nontuberculous mycobacteria increasingly are being recognized as causative organisms for granulomatous lesions developing subacutely or even months after receiving a new tattoo.5,7 Local and systemic viral infections also may be transmitted during tattooing; cases of tattoo-transmitted viral warts, molluscum contagiosum, and hepatitis B and C viruses all have been observed.5,6,8 Herpes simplex virus transmission (colloquially termed herpes compunctorum) and HIV transmission through tattooing also are hypothesized to be possible, though there is a paucity of known cases for each.8,9

Chronic inflammatory, granulomatous, or neoplastic lesions may arise within tattooed skin months or years after tattooing. Foreign body granulomas, sarcoidosis, pseudolymphoma, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, and keratoacanthoma are some representative entities.3,5 Cases of cancerous lesions in tattooed skin have been documented, but their incidence appears similar to nontattooed skin.3 These broad categories of lesions are clinically diverse but may be difficult to definitively diagnose on examination alone; therefore, a biopsy should be strongly considered for any subacute to chronic skin lesions within a tattoo. Patients may be hesitant to disrupt the cosmesis of a tattoo but should be counseled on the attendant risks and benefits to make an informed decision regarding biopsy.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

- Wenzel SM, Rittmann I, Landthaler M, et al. Adverse reactions after tattooing: review of the literature and comparison to results of a survey. Dermatology. 2013;226:138-147.

- Liszewski W, Kream E, Helland S, et al. The demographics and rates of tattoo complications, regret, and unsafe tattooing practices: a crosssectional study. Dermatol Surg. 2015;41:1283-1289.

- Islam PS, Chang C, Selmi C, et al. Medical complications of tattoos: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2016;50:273-286.

- Serup J, Carlsen KH, Sepehri M. Tattoo complaints and complications: diagnosis and clinical spectrum. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2015;48:48-60.

- Simunovic C, Shinohara MM. Complications of decorative tattoos: recognition and management. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2014;15:525-536.

- Kazandjieva J, Tsankov N. Tattoos: dermatological complications. Clin Dermatol. 2007;25:375-382.

- Sergeant A, Conaglen P, Laurenson IF, et al. Mycobacterium chelonae infection: a complication of tattooing. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2013;38:140-142.

- Cohen PR. Tattoo-associated viral infections: a review. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2021;14:1529-1540.

- Doll DC. Tattooing in prison and HIV infection. Lancet. 1988;1:66-67.

A healthy 21-year-old woman presented with a pruritic papulovesicular rash on the left arm of 2 days’ duration. The day before rash onset, she received a black ink tattoo on the left arm to complete the second half of a monochromatic sleevestyle design. She previously underwent initial tattooing of the left arm by the same artist 2 weeks prior and experienced a similar but less extensive rash that self-resolved after 1 week. She had 8 older tattoos on various other body parts and denied any reactions. Physical examination showed numerous scattered papules and papulovesicles confined to areas of newly tattooed skin throughout the left arm. In the larger swaths of the tattoo, the papules coalesced into well-defined plaques. There was a discrete rim of faint erythema bordering the newly tattooed skin. No erosions, ulcerations, or purulent areas were observed, and there was no tenderness or excess warmth of the affected skin. Adjacent previously tattooed areas of the left arm were unaffected.

Pruritic Axillary Plaques

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

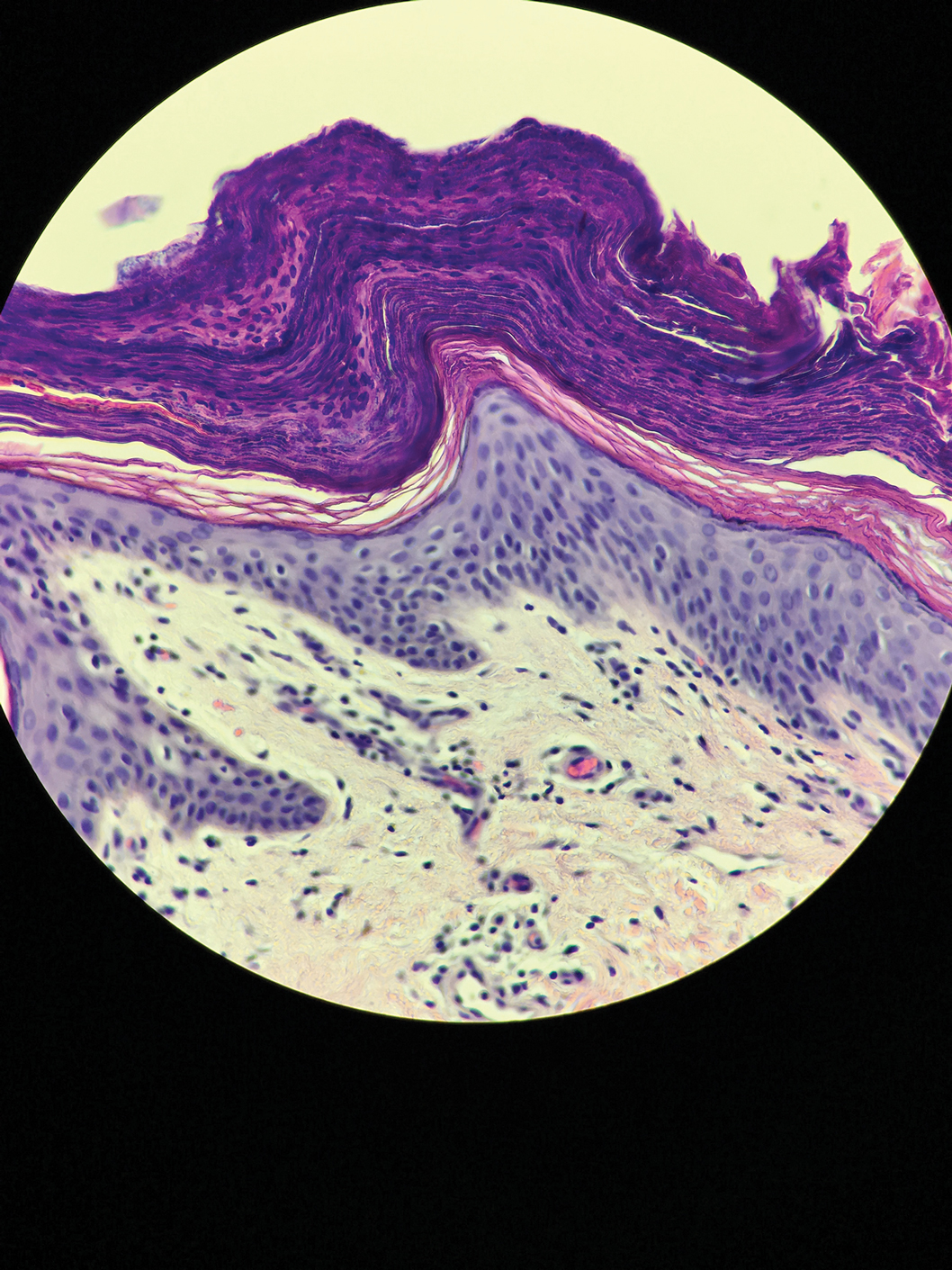

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

The Diagnosis: Granular Parakeratosis

Microscopic examination of a punch biopsy from the left axilla revealed verruciform epidermal hyperplasia with overlying parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum (Figure). There was no evidence of acantholysis, dyskeratosis, epidermal neutrophils, or neutrophilic microabscesses.

The patient's history and characteristic histopathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of granular parakeratosis (GP). He was instructed to discontinue his current antiperspirant and began treatment with topical fluocinolone oil 0.01% every morning and urea cream 20% every night. Complete resolution was achieved within 2 weeks, and he reported no recurrence at a 2-year follow-up visit.

Granular parakeratosis is a rare idiopathic skin condition characterized by hyperkeratotic papules and plaques, most often in intertriginous areas. Described by Northcutt et al1 as a contact reaction to antiperspirant in the axillae, GP also has been reported in the submammary and inguinal creases2 and rarely in nonintertriginous sites such as the abdomen.3 Although deodorants and antiperspirants in roll-on or stick form classically are implicated in GP, the condition also has been observed with exposure to laundry detergents containing benzalkonium chloride.4 Lesions with GP histology also have been incidentally observed in association with dermatophytosis,5 dermatomyositis,6 molluscum contagiosum,7 and carcinomas.8 Ding et al9 proposed that GP be reclassified as a reaction pattern observed in the skin as opposed to being a distinct disease entity.

Clinically, GP presents as pruritic intertriginous papules and coalescent plaques that most commonly are seen in the axillae but also may involve the groin or other sites.2,3 Both pruritus and disease burden can be aggravated by heat, sweating, or friction. There may be a history of a new irritant exposure prior to symptom onset, but GP has been observed in the absence of identifiable exposures and in the setting of long-term antiperspirant or deodorant use.3 Although a family history may be helpful, it can be difficult to distinguish GP from entities such as Hailey-Hailey disease or Darier disease based on history and examination alone; a biopsy often is necessary for definitive diagnosis.

Histologically, GP demonstrates acanthosis with parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules in the stratum corneum.1 The stratum granulosum is preserved. On cursory examination, GP may resemble a psoriasiform dermatosis as can be seen in inverse psoriasis; however, neutrophilic microabscesses and infiltrates are not seen. Absence of acantholysis and dyskeratosis further differentiates GP from the clinically similar Hailey-Hailey disease and Darier disease. Spongiosis that is prominently found in allergic contact dermatitis also is absent.

Although a benign disorder, GP warrants treatment to achieve symptomatic relief. A mainstay of treatment is to eliminate exposure to suspected aggravating or inciting factors such as antiperspirants or deodorants. A variety of treatments including laser therapy, corticosteroids, isotretinoin, and vitamin D analogs such as calcipotriene and calcitriol have been reported to be effective treatments of GP in case studies and series.3,10 Large-scale clinical trials are not available because of the rarity of this condition. Our patient's clinical course suggests topical fluocinolone and urea in combination can be considered to achieve rapid resolution.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Neidt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Robinson AJ, Foster RS, Halbert AR, et al. Granular parakeratosis induced by benzalkonium chloride exposure from laundry rinse aids. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:E138-E140.

- Resnik KS, Kantor GR, DiLeonardo M. Dermatophyte-related granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:70-71.

- Pock L, Hercogová J. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with dermatomyositis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:147-149.

- Pock L, Cermáková A, Zipfelová J, et al. Incidental granular parakeratosis associated with molluscum contagiosum. Am J Dermatopathol. 2006;28:45-47.

- Resnik KS, DiLeonardo M. Incidental granular parakeratotic cornification in carcinomas. Am J Dermatopathol. 2007;29:264-269.

- Ding CY, Liu H, Khachemoune A. Granular parakeratosis: a comprehensive review and a critical reappraisal. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:495-500.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

A 42-year-old man presented with pruritic axillary plaques of 6 months’ duration that were exacerbated by heat and friction. He maintained a very active lifestyle and used an antiperspirant regularly. He denied any family history of similar lesions. Thick emollients provided no relief. Physical examination demonstrated numerous soft, hyperkeratotic, waxy, yellowish brown papules coalescing into plaques localized to the bilateral axillary vaults, affecting the right axilla more than the left. Although some papules were firmly adherent to the skin, others were friable and easily removed with a cotton-tipped applicator, revealing an underlying, faintly erythematous base.