User login

2019 Update on cervical disease

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

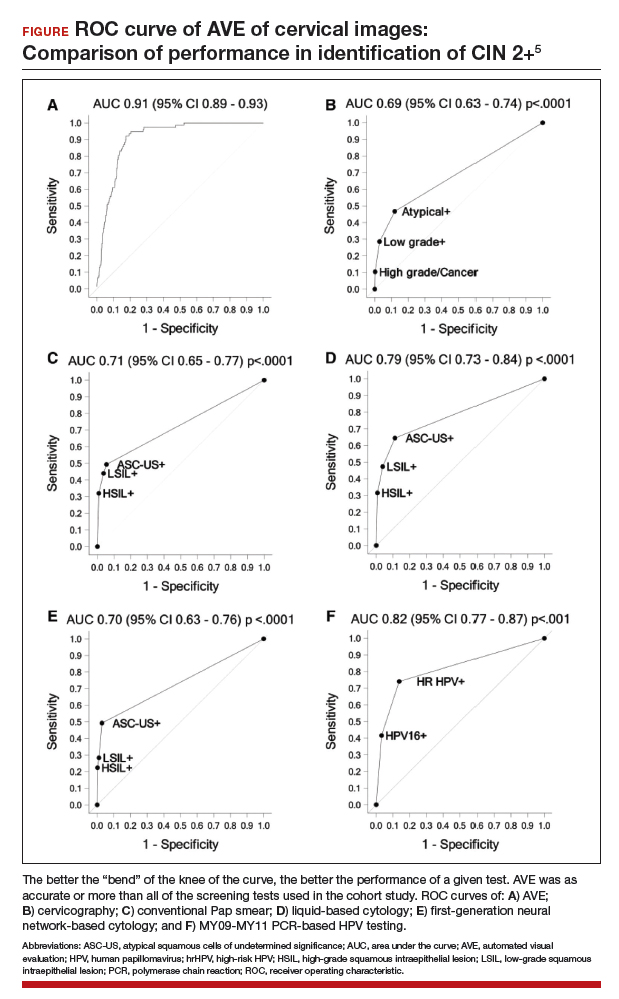

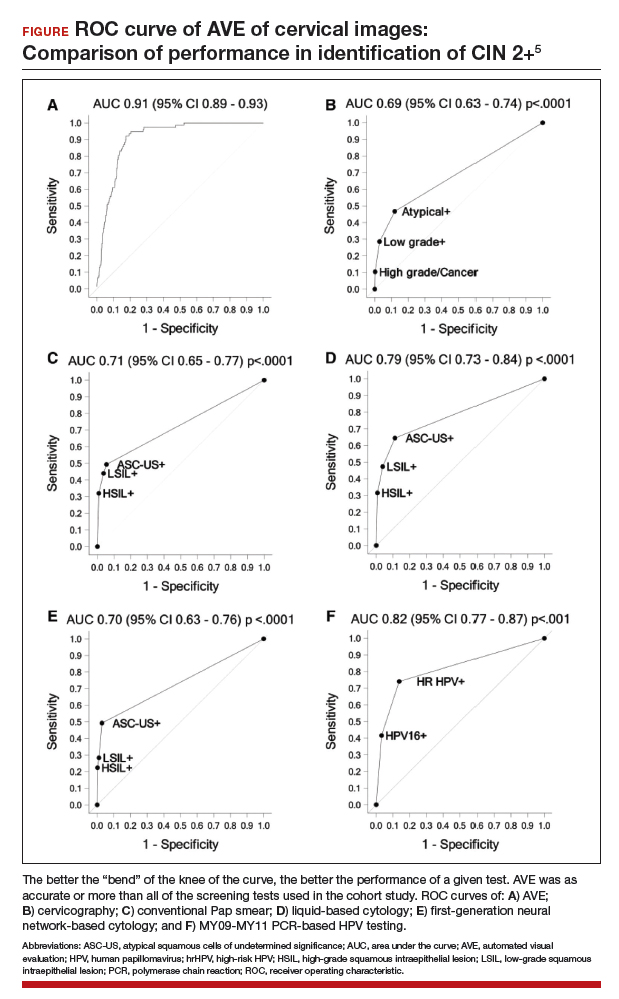

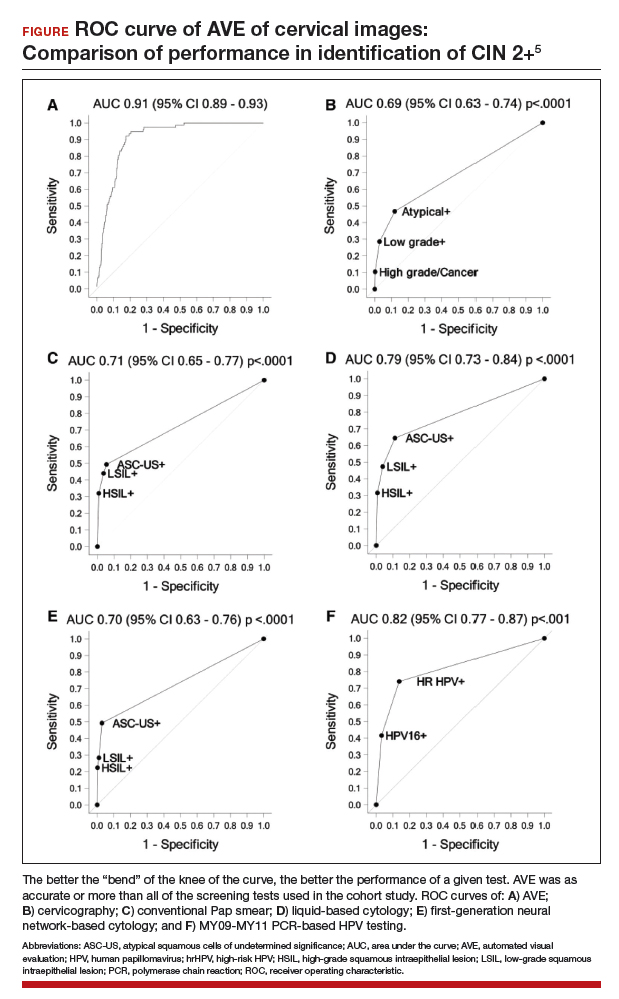

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

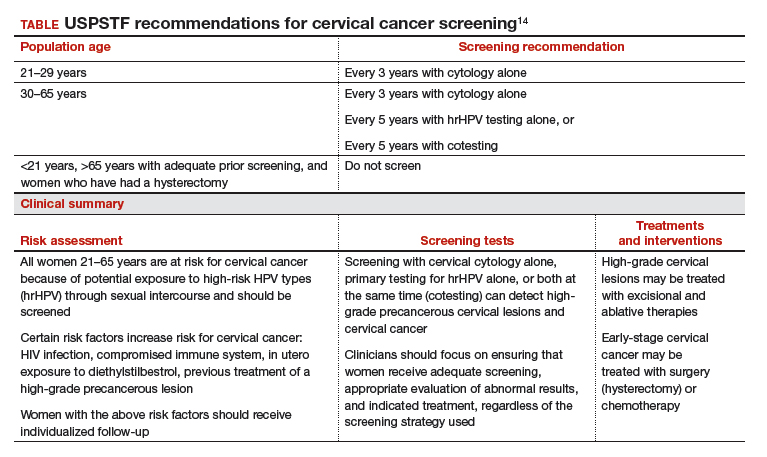

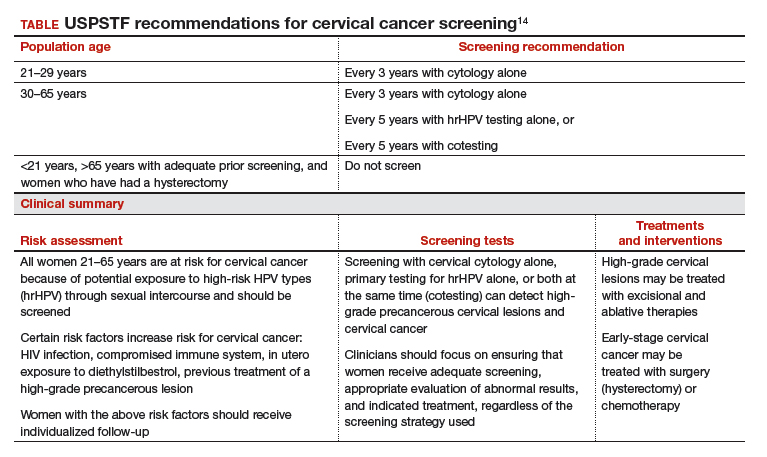

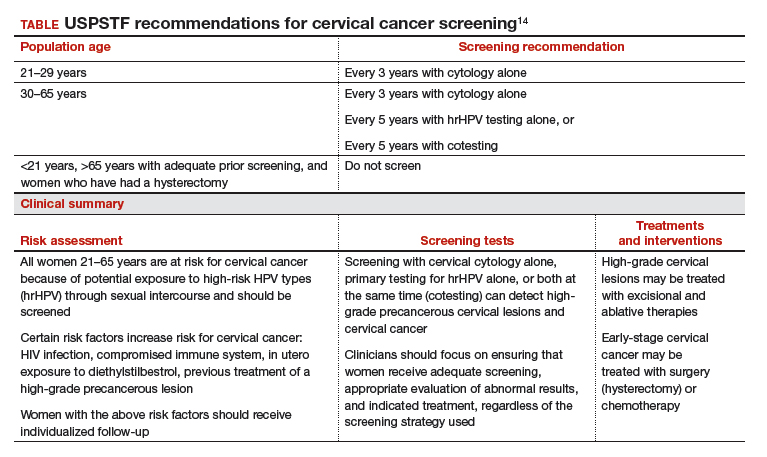

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

Cervical cancer rates remain low in the United States, with the incidence having plateaued for decades. And yet, in 2019, more than 13,000 US women will be diagnosed with cervical cancer.1 Globally, in 2018 almost 600,000 women were diagnosed with cervical cancer2; it is the fourth most frequent cancer in women. This is despite the fact that we have adequate primary and secondary prevention tools available to minimize—and almost eliminate—cervical cancer. We must continue to raise the bar for preventing, screening for, and managing this disease.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines provide a highly effective primary prevention strategy, but we need to improve our ability to identify and diagnose dysplastic lesions prior to the development of cervical cancer. Highly sensitive HPV testing and cytology is a powerful secondary prevention approach that enables us to assess a woman’s risk of having precancerous cells both now and in the near future. These modalities have been very successful in decreasing the incidence of cervical cancer in the United States and other areas with organized screening programs. In low- and middle-income countries, however, access to, availability of, and performance with these modalities is not optimal. Innovative strategies and new technologies are being evaluated to overcome these limitations.

Advances in radiation and surgical technology have enabled us to vastly improve cervical cancer treatment. Women with early-stage cervical cancer are candidates for surgical management, which frequently includes a radical hysterectomy and lymph node dissection. While these surgeries traditionally have been performed via an exploratory laparotomy, minimally invasive techniques (laparoscopic and robot-assisted surgical techniques) have decreased the morbidity with these surgeries. Notable new studies have shed light on the comparative effectiveness of minimally invasive technologies and have shown us that new is not always better.

The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently released its updated cervical cancer screening guidelines. The suggested approach to screening differs from previous recommendations. HPV testing as a primary test (that is, HPV testing alone or followed by cytology) takes the spotlight now, according to the analysis by the Task Force.

In this Update, we highlight important studies published in the past year that address these issues.

Continue to: New tech's potential to identify high-grade...

New tech's potential to identify high-grade cervical dysplasia may be a boon to low-resource settings

Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

When cervical screening tests like cytology and HPV testing show abnormal results, colposcopy often is recommended. The goal of colposcopy is to identify the areas that might harbor a high-grade precancerous lesion or worse. The gold standard in this case, however, is histology, not colposcopic impression, as many studies have shown that colposcopy without biopsies is limited and that performance is improved with more biopsies.3,4

Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) is an approach used often in low-resource settings where visual impression is the gold standard. However, as with colposcopy, a visual evaluation without histology does not perform well, and often women are overtreated. Many attempts have been made with new technologies to overcome the limitations of time, cost, and workforce required for cytology and histology services. New disruptive technologies may be able to surmount human limitations and improve on not only VIA but also the need for histology.

Novel technology uses images to develop algorithm with predictive ability

In a recent observational study, Hu and colleagues used images that were collected during a large population study in Guanacaste, Costa Rica.5 More than 9,000 women were followed for up to 7 years, and cervical photographs (cervigrams) were obtained. Well-annotated histopathology results were obtained for women with abnormal screening, and 279 women had a high-grade dysplastic lesion or cancer.

Cervigrams from women with high-grade lesions and matched controls were collected, and a deep learning-based algorithm using artificial intelligence technology was developed using 70% of the images. The remaining 30% of images were used as a validation set to test the algorithm's ability to "predict" high-grade dysplasia without knowing the final result.

Findings. Termed automated visual evaluation (AVE), this new technology demonstrated a very accurate ability to identify high-grade dysplasia or worse, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.91 from merely a cervicogram (FIGURE). This outperformed conventional Pap smears (AUC, 0.71), liquid-based cytology (AUC, 0.79) and, surprisingly, highly sensitive HPV testing (AUC, 0.82) in women in the prime of their screening ages (>25 years of age).

Colposcopy remains the gold standard for evaluating abnormal cervical cancer screening tests in the United States. But can we do better for our patients using new technologies like AVE? If validated in large-scale trials, AVE has the potential to revolutionize cervical cancer screening in low-resource settings where follow-up and adequate histology services are limited or nonexistent. Future large studies are necessary to evaluate the role of AVE alone versus in combination with other diagnostic testing (such as HPV testing) to detect cervical lesions globally.

Continue to: Data offer persuasive evidence...

Data offer persuasive evidence to abandon minimally invasive surgery in management of early-stage cervical cancer

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Over the past decade, gynecologic cancer surgery has shifted from what routinely were open procedures to the adoption of minimally invasive techniques. Recently, a large, well-designed prospective study and a large retrospective study both demonstrated worse outcomes with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy (MIRH) as compared with traditional open radical abdominal hysterectomy (RAH). These 2 landmark studies, initially presented at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology's 2018 annual meeting and later published in the New England Journal of Medicine, have really affected the gynecologic oncology community.

Shorter overall survival in women who had MIRH

Melamed and colleagues conducted a large, retrospective US-based study to evaluate all-cause mortality in women with cervical cancer who underwent MIRH compared with those who had RAH.6 The authors also sought to evaluate national trends in 4-year relative survival rates after minimally invasive surgery was adopted.

The study included 2,461 women who met the inclusion criteria; 49.8% (1,225) underwent MIRH procedures and, of those, 79.8% (978) had robot-assisted laparoscopy. Most women had stage IB1 tumors (88%), and most carcinomas were squamous cell (61%); 40.6% of tumors were less than 2 cm in size. There were no differences between the 2 groups with respect to rates of positive parametria, surgical margins, and lymph node involvement. Administration of adjuvant therapy, in those who qualified, was also similar between groups.

Results. At a median follow-up of 45 months, 94 deaths occurred in the minimally invasive group and 70 in the open surgery group. The risk of death at 4 years was 9.1% in the minimally invasive group versus 5.3% in the open surgery group, with a 65% higher risk of death from any cause, which was highly statistically significant.

Prospective trial showed MIRH was associated with lower survival rates

From 2008 to 2017, Ramirez and colleagues conducted a phase 3, multicenter, randomized controlled trial to prospectively establish the noninferiority of MIRH compared with RAH.7 The study included 631 women from 33 centers. The prespecified expected disease-free survival rate was 90% at 4.5 years.

To be included as a site, centers were required to submit details from 10 minimally invasive cases as well as 2 unedited videos for review by the trial management committee. In contrast to Melamed and colleagues' retrospective study, of the 319 procedures that were classified as minimally invasive, only 15.6% were robotically assisted. Similarly, most women had stage IB1 tumors (91.9%), and most were squamous cell carcinomas (67%). There were also no differences in the postoperative pathology findings or the need for adjuvant therapy administered between groups. The median follow-up was 2.5 years.

Results. At that time there were 27 recurrences in the MIRH group and 7 in the RAH group; there were also 19 deaths after MIRH and 3 after RAH. Disease-free survival at 4.5 years was 86% with MIRH versus 96.5% with RAH. Reported 3-year disease-free survival and overall survival were also significantily lower in the minimally invasive subgroup (91.2% vs 97.1%, 93.8% vs 99.0%, respectively).

Study limitations. Criticisms of this trial are that noninferiority could not be declared; in addition, the investigators were unable to complete enrollment secondary to early enrollment termination after the data and safety monitoring board raised survival concerns.

Many argue that subgroup analyses suggest a lower risk of poor outcomes in patients with smaller tumors (<2 cm); however, it is critical to note that this study was not powered to detect these differences.

The evidence is compelling and demonstrates potentially worse disease-related outcomes using MIRH when compared to traditional RAH with respect to cervical cancer recurrence, rates of death, and disease-free and overall survival. Several hypotheses have been proposed, and future research is needed to elucidate the differences in variables responsible for the outcomes demonstrated in these studies. Although there has been no ban on robot-assisted surgical devices or traditional minimally invasive techniques, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network has updated its recommendations to include careful counseling of patients who require a surgical approach for the management of early-stage cervical cancer.

Continue to: USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening...

USPSTF updated guidance on cervical cancer screening

Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

Past guidelines for cervical cancer screening have included testing for high-risk HPV (hrHPV) as a cotest with cytology or for triage of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) in women aged 30 to 65 years.8 The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology, with other stakeholder organizations, issued interim guidance for primary HPV testing--that is, HPV test first and, in the case of non-16/18 hrHPV types, cytology as a triage. The most recent evidence report and systematic review by Melnikow and colleagues for the USPSTF offers an in-depth analysis of risks, benefits, harms, and value of cotesting and other management strategies.9

Focus on screening effectiveness

Large trials of cotesting were conducted in women aged 25 to 65.10-13 These studies all consistently showed that primary hrHPV screening led to a statistically significant increased detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 3+ in the initial round of screening, with a relative risk of detecting CIN 3+ ranging from 1.61 to 7.46 compared with cytology alone.

Four additional studies compared cotesting with conventional cytology for the detection of CIN 3+. None of these trials demonstrated a significantly higher detection rate of CIN 3+ with cotesting compared with conventional cytology testing alone. Notably, the studies reviewed were performed in European countries that had organized screening programs in place and a nationalized health care system. Thus, these data may not be as applicable to women in the United States, particularly to women who have limited health care access.

Risks of screening

In the same studies reviewed for screening effectiveness, the investigators found that overall, screening with hrHPV primary or cotesting was associated with more false-positive results and higher colposcopy rates. Women screened with hrHPV alone had a 7.9% referral rate to colposcopy, while those screened with cytology had a 2.8% referral rate to colposcopy. Similarly, the rate of biopsy was higher in the hrHPV-only group (3.2% vs 1.3%).

Overall, while cotesting might have some improvement in performance compared with hrHPV as a single modality, there might be risks of overreferral to colposcopy and overtreatment with additional cytology over hrHPV testing alone.

This evidence review also included an analysis of more potential harms. Very limited evidence suggests that positive hrHPV test results may be associated with greater psychological harm, including decreased sexual satisfaction, increased anxiety and distress, and worse feelings about sexual partners, than abnormal cytology results. These were assessed, however, 1 to 2 weeks after the test results were provided to the patients, and long-term assessment was not done.

New recommendations from the USPSTF

Based on these data, the USPSTF issued new recommendations regarding screening (TABLE).14 For women aged 21 to 29, cytology alone should be used for screening every 3 years. Women aged 30 to 65 can be screened with cytology alone every 3 years, with hrHPV testing alone every 5 years, or with cotesting every 5 years.

Primary screening with hrHPV is more effective in diagnosing a CIN 3+ than cytology alone. Cotesting with cytology and hrHPV testing appears to have limited performance improvement, with potential harm, compared with hrHPV testing alone in diagnosing CIN 3+. The Task Force recommendation is hrHPV testing alone or cotesting every 5 years.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7-34.

- World Health Organization website. Cervical cancer. https://www.who.int/cancer/prevention/diagnosis-screening/cervical-cancer/en/. Accessed April 17, 2019.

- Wentzensen N, Walker JL, Gold MA, et al. Multiple biopsies and detection of cervical cancer precursors at colposcopy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:83-89.

- Gage JC, Hanson VW, Abbey K, et al. Number of cervical biopsies and sensitivity of colposcopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:264-272.

- Hu L, Bell D, Antani S, et al. An observational study of deep learning and automated evaluation of cervical images for cancer screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019;doi:10.1093/jnci/djy225.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

- Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson HW, et al; ACS-ASCCP-ASCP Cervical Cancer Guideline Committee. American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology screening guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:147-172.

- Melnikow J, Henderson JT, Burda BU, et al. Screening for cervical cancer with high-risk human papillomavirus testing: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:687-705.

- Canfell K, Caruana M, Gebski V, et al. Cervical screening with primary HPV testing or cytology in a population of women in which those aged 33 years or younger had previously been offered HPV vaccination: results of the Compass pilot randomised trial. PLoS Med. 2017;14:e1002388. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002388.

- Leinonen MK, Nieminen P, Lonnberg S, et al. Detection rates of precancerous and cancerous cervical lesions within one screening round of primary human papillomavirus DNA testing: prospective randomised trial in Finland. BMJ. 2012;345:e7789.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Ronco G, Fioprgi-Rossi P, Carozzi F, et al; New Technologies for Cervical Cancer screening (NTCC) Working Group. Efficacy of human papillomavirus testing for the detection of invasive cervical cancers and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:249-257.

- US Preventive Services Task Force, Curry SJ, Krist AH, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.