User login

Endoscopic weight loss surgery cuts costs, side effects

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

Obese patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty had significantly fewer complications and shorter hospital stays than did those who had laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy or laparoscopic band placement, according to results from a study of 278 adults. The data were presented at the annual Digestive Disease Week®.

Overall, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty (ESG) experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of those who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) and 9% of those who underwent laparoscopic band placement (LAGB).

ESG, which reduces gastric volume by use of an endoscopic suturing system of full-thickness sutures through the greater curvature of the stomach, is becoming a popular weight-loss procedure for patients with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 who are poor candidates for laparoscopic surgery or who would prefer a less invasive procedure, according to Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, of Cornell University, New York.

Dr. Sharaiha and her colleagues randomized 91 patients to ESG, 120 to LSG, and 67 to LAGB. Patient demographic characteristics, including age, gender, and diabetes, were similar among the three groups. However, patients in the LSG group had a higher average BMI than did the LAGB and ESG groups (47.3 kg/m2, 45.7 kg/m2, and 38.8 kg/m2, respectively). In addition, the incidence of hypertension, and hyperlipidemia was significantly higher in each of the surgical groups compared to the ESG group (P less than .01).

The average postprocedure hospital stay was 0.13 days for ESG patients compared with 3.09 days for LSG patients and 1.68 days for LAGB patients. ESG also had the lowest cost of the three procedures, averaging $12,000 for the procedure compared to $22,000 for LSG and $15,000 for LAGB.

After 1 year, patients in the LSG group had the greatest percentage of total body weight loss (29.3%), followed by ESG patients (17.6%), and LAGB patients (14.5%). Rates of leaks, pulmonary embolism events, and 90-day readmission were not significantly different among the groups.

The study results do not imply that ESG will replace either LAGB or LSG for weight loss, Dr. Sharaiha noted, but the results suggest that ESG is a viable option for some patients.

Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Digestive Disease Week® is jointly sponsored by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE), and the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT).

FROM DDW

Key clinical point: Endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty is a viable option for patients seeking weight loss but wishing to avoid major surgery.

Major finding: After 1 year, 1% of patients who underwent endoscopic sleeve gastroplasty experienced adverse events, compared with 8% of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy patients, and 9% of laparoscopic band placement patients.

Data source: A randomized trial of 278 obese adults who underwent one of three weight loss procedures.

Disclosures: Dr. Sharaiha had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The future of GI: A choice between ‘care assembly’ or skilled risk management

BOSTON – Gastroenterology is becoming a game of risk: It’s either learn to leverage risk through the creation of advanced alternative payment methods (APM) under Medicare’s new Quality Payment Program or risk losing money through the commoditization of the field, according to an expert.

“Our culture right now is one where we get paid for making widgets,” said Lawrence Kosinski, MD, a practice councilor on the American Gastroenterological Association Governing Board and former chairman of its Practice Management and Economics Committee. He made his remarks in an interview in advance of his presentation at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “The more colonoscopies we do, the more money we make. The more we can charge for those colonoscopies and get collected, the better things are for us.”

“Over 80% of the cost of health care is for the management of chronic disease. We happen to have a very expensive set of chronic diseases that we take care of in GI, very complicated illnesses. We need to leverage the management of those patients, but we need to be able to show how our work decreases the overall cost of care so that we can get a piece of that risk premium,” he said.

In his own practice, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues have created an APM – the first novel APM to be recommended to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for approval by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee – that is based on better patient risk assessment, combined with earlier patient engagement.

After discovering in 2013 that one of his payers was spending $24,000 annually on patients with inflammatory bowel disease and that two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are admitted to the hospital had not had a CPT code issued in the 30 days before admission, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues wanted to see if they could offer the insurer value by decreasing that hospitalization rate.

Using proprietary algorithms rooted in thorough patient risk assessment according to published guidelines for the management of patients with Crohn’s disease, they created a patient platform – coined ProjectSonar – that alerts their Crohn’s patients on their smart phones, engages them in a short survey, and provides them with instant feedback on their disease status and care needs based on their responses. Survey results are sent to the Web and to nurse case managers at the practice, who follow up with the patient accordingly.

A year-long pilot program of the patient portal with 50 people in the study population showed more than a 600% return on the cost of investment in the proprietary software, with an average of $6,000 in medical savings for test subjects who responded to texts, compared with controls who did not receive smart phone texts, for a total savings of more than half a million dollars. “All of the savings come from the patients who respond,” Dr. Kosinski said, noting that, in his practice, they now have a sustained patient response rate of more than 80% and that it helps to have the physician emphasize use of the platform to the patient.

“Patients love it. It is almost like chronic disease concierge medicine they don’t have to pay for,” Dr. Kosinski said during his presentation at the meeting, adding that the insurer likes it because it cuts costs, and physicians like it because they don’t have to take less reimbursement to help the insurer realize gains.

“We risk assess every patient, something the majority of doctors don’t do but [that] insurance companies do all the time,” Dr. Kosinski said in an interview after his presentation. “Then we apply the appropriate treatment using the scientific methods in the published guidelines. Then we analyze the data, which helps us refine our assessments and predict our costs of care in this population.”

Knowing the base cost of care for specific patient populations helps define the margin of financial risk he and his colleagues can tolerate. A gastroenterology practice that operates as a risk-bearing entity could theoretically offer to contract with affordable care organizations to manage IBD or other GI-type conditions, he said.

By learning to assess, measure, and leverage risk, gastroenterologists can become sought after for the value they provide rather than for the care they “assemble,” something Dr. Kosinski said is of rising concern as the Affordable Care Act has driven a lot of consolidation, with hospital systems buying up primary care physicians and specialists.

Otherwise, he said, “We’re just going to be commoditized proceduralists.”

Dr. Kosinski is president of SonarMDTM.

BOSTON – Gastroenterology is becoming a game of risk: It’s either learn to leverage risk through the creation of advanced alternative payment methods (APM) under Medicare’s new Quality Payment Program or risk losing money through the commoditization of the field, according to an expert.

“Our culture right now is one where we get paid for making widgets,” said Lawrence Kosinski, MD, a practice councilor on the American Gastroenterological Association Governing Board and former chairman of its Practice Management and Economics Committee. He made his remarks in an interview in advance of his presentation at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “The more colonoscopies we do, the more money we make. The more we can charge for those colonoscopies and get collected, the better things are for us.”

“Over 80% of the cost of health care is for the management of chronic disease. We happen to have a very expensive set of chronic diseases that we take care of in GI, very complicated illnesses. We need to leverage the management of those patients, but we need to be able to show how our work decreases the overall cost of care so that we can get a piece of that risk premium,” he said.

In his own practice, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues have created an APM – the first novel APM to be recommended to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for approval by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee – that is based on better patient risk assessment, combined with earlier patient engagement.

After discovering in 2013 that one of his payers was spending $24,000 annually on patients with inflammatory bowel disease and that two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are admitted to the hospital had not had a CPT code issued in the 30 days before admission, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues wanted to see if they could offer the insurer value by decreasing that hospitalization rate.

Using proprietary algorithms rooted in thorough patient risk assessment according to published guidelines for the management of patients with Crohn’s disease, they created a patient platform – coined ProjectSonar – that alerts their Crohn’s patients on their smart phones, engages them in a short survey, and provides them with instant feedback on their disease status and care needs based on their responses. Survey results are sent to the Web and to nurse case managers at the practice, who follow up with the patient accordingly.

A year-long pilot program of the patient portal with 50 people in the study population showed more than a 600% return on the cost of investment in the proprietary software, with an average of $6,000 in medical savings for test subjects who responded to texts, compared with controls who did not receive smart phone texts, for a total savings of more than half a million dollars. “All of the savings come from the patients who respond,” Dr. Kosinski said, noting that, in his practice, they now have a sustained patient response rate of more than 80% and that it helps to have the physician emphasize use of the platform to the patient.

“Patients love it. It is almost like chronic disease concierge medicine they don’t have to pay for,” Dr. Kosinski said during his presentation at the meeting, adding that the insurer likes it because it cuts costs, and physicians like it because they don’t have to take less reimbursement to help the insurer realize gains.

“We risk assess every patient, something the majority of doctors don’t do but [that] insurance companies do all the time,” Dr. Kosinski said in an interview after his presentation. “Then we apply the appropriate treatment using the scientific methods in the published guidelines. Then we analyze the data, which helps us refine our assessments and predict our costs of care in this population.”

Knowing the base cost of care for specific patient populations helps define the margin of financial risk he and his colleagues can tolerate. A gastroenterology practice that operates as a risk-bearing entity could theoretically offer to contract with affordable care organizations to manage IBD or other GI-type conditions, he said.

By learning to assess, measure, and leverage risk, gastroenterologists can become sought after for the value they provide rather than for the care they “assemble,” something Dr. Kosinski said is of rising concern as the Affordable Care Act has driven a lot of consolidation, with hospital systems buying up primary care physicians and specialists.

Otherwise, he said, “We’re just going to be commoditized proceduralists.”

Dr. Kosinski is president of SonarMDTM.

BOSTON – Gastroenterology is becoming a game of risk: It’s either learn to leverage risk through the creation of advanced alternative payment methods (APM) under Medicare’s new Quality Payment Program or risk losing money through the commoditization of the field, according to an expert.

“Our culture right now is one where we get paid for making widgets,” said Lawrence Kosinski, MD, a practice councilor on the American Gastroenterological Association Governing Board and former chairman of its Practice Management and Economics Committee. He made his remarks in an interview in advance of his presentation at the 2017 AGA Tech Summit sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. “The more colonoscopies we do, the more money we make. The more we can charge for those colonoscopies and get collected, the better things are for us.”

“Over 80% of the cost of health care is for the management of chronic disease. We happen to have a very expensive set of chronic diseases that we take care of in GI, very complicated illnesses. We need to leverage the management of those patients, but we need to be able to show how our work decreases the overall cost of care so that we can get a piece of that risk premium,” he said.

In his own practice, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues have created an APM – the first novel APM to be recommended to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services for approval by the Physician-Focused Payment Model Technical Advisory Committee – that is based on better patient risk assessment, combined with earlier patient engagement.

After discovering in 2013 that one of his payers was spending $24,000 annually on patients with inflammatory bowel disease and that two-thirds of patients with inflammatory bowel disease who are admitted to the hospital had not had a CPT code issued in the 30 days before admission, Dr. Kosinski and his colleagues wanted to see if they could offer the insurer value by decreasing that hospitalization rate.

Using proprietary algorithms rooted in thorough patient risk assessment according to published guidelines for the management of patients with Crohn’s disease, they created a patient platform – coined ProjectSonar – that alerts their Crohn’s patients on their smart phones, engages them in a short survey, and provides them with instant feedback on their disease status and care needs based on their responses. Survey results are sent to the Web and to nurse case managers at the practice, who follow up with the patient accordingly.

A year-long pilot program of the patient portal with 50 people in the study population showed more than a 600% return on the cost of investment in the proprietary software, with an average of $6,000 in medical savings for test subjects who responded to texts, compared with controls who did not receive smart phone texts, for a total savings of more than half a million dollars. “All of the savings come from the patients who respond,” Dr. Kosinski said, noting that, in his practice, they now have a sustained patient response rate of more than 80% and that it helps to have the physician emphasize use of the platform to the patient.

“Patients love it. It is almost like chronic disease concierge medicine they don’t have to pay for,” Dr. Kosinski said during his presentation at the meeting, adding that the insurer likes it because it cuts costs, and physicians like it because they don’t have to take less reimbursement to help the insurer realize gains.

“We risk assess every patient, something the majority of doctors don’t do but [that] insurance companies do all the time,” Dr. Kosinski said in an interview after his presentation. “Then we apply the appropriate treatment using the scientific methods in the published guidelines. Then we analyze the data, which helps us refine our assessments and predict our costs of care in this population.”

Knowing the base cost of care for specific patient populations helps define the margin of financial risk he and his colleagues can tolerate. A gastroenterology practice that operates as a risk-bearing entity could theoretically offer to contract with affordable care organizations to manage IBD or other GI-type conditions, he said.

By learning to assess, measure, and leverage risk, gastroenterologists can become sought after for the value they provide rather than for the care they “assemble,” something Dr. Kosinski said is of rising concern as the Affordable Care Act has driven a lot of consolidation, with hospital systems buying up primary care physicians and specialists.

Otherwise, he said, “We’re just going to be commoditized proceduralists.”

Dr. Kosinski is president of SonarMDTM.

FROM THE 2017 AGA TECH SUMMIT

BUN increase tracks with upper GI bleeding outcomes

In patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (UGIB), increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels at 24 hours were associated with worse outcomes. The marker, already proven useful in acute pancreatitis, could help physicians determine a patient’s prognosis.

Existing measures of UGIB risk are effective, but only about 30% of physicians ever calculate risk scores when evaluating UGIB patients, perhaps because they require measurements at multiple time points. “We personally think the reason for this is the busyness of clinical practices, especially the acute nature of upper GI bleeding. It’s often hard to step back to calculate a score that has multiple variables,” said study author Navin Kumar, MD, a fellow in gastroenterology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1533).

Like acute pancreatitis, upper GI bleeding requires resuscitation management, which suggested that BUN levels might be a useful marker in this condition as well. To find out, the researchers analyzed data from 357 patients who were treated at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital emergency department and ultimately hospitalized for UGIB during 2004-2014.

The researchers analyzed BUN levels measured at admission and at the time closest to 24 hours after hospitalization, which ranged from 6 hours to 48 hours.

Thirty-seven patients (10%) experienced an increase in BUN level, while all the rest had levels that stayed steady or decreased. Those patients with BUN increases had a lower mean Glasgow-Blatchford score (7.8 vs. 9.6; P =.010), but there was no difference in AIMS65 scores.

Patients with BUN increases had greater odds of the composite outcome, which included inpatient death from any cause, inpatient rebleeding, a need for surgical or radiologic intervention, and/or a need for endoscopic reintervention during hospitalization (22% vs. 9%; P =.014). Inpatient mortality was higher in the increased BUN group (8% vs. 1%; P =.004).

Overall, BUN increase at 24 hours was associated with an odds ratio of 2.75 for the composite outcome (95% confidence interval, 1.13-6.70; P = .026).

A potential limitation to using the BUN is that it could just be catching patients with underlying renal disease. But when researchers adjusted for this, the odds ratio for increased BUN remained significant (OR, 3.00; P =.021).

“The nice part of the study is that it’s so easy to interpret and apply in a clinical setting. You just need two data points: BUN at presentation and at 24 hours. If the BUN level has risen, you need to have a higher degree of suspicion for the prognosis of those patients,” said Dr. Kumar.

The downside to BUN is that it doesn’t provide information for the first 24 hours. For that reason, BUN shouldn’t replace measures like the Glasgow-Blatchford score and the AIMS65 score. “But it’s very helpful to use this change in BUN score to get a sense of where the patient is trending. If it’s rising, there’s a higher risk of worse outcomes, and this could influence decisions about whether the patient should be in the ICU or the medical ward,” said Dr. Kumar.

In patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (UGIB), increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels at 24 hours were associated with worse outcomes. The marker, already proven useful in acute pancreatitis, could help physicians determine a patient’s prognosis.

Existing measures of UGIB risk are effective, but only about 30% of physicians ever calculate risk scores when evaluating UGIB patients, perhaps because they require measurements at multiple time points. “We personally think the reason for this is the busyness of clinical practices, especially the acute nature of upper GI bleeding. It’s often hard to step back to calculate a score that has multiple variables,” said study author Navin Kumar, MD, a fellow in gastroenterology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1533).

Like acute pancreatitis, upper GI bleeding requires resuscitation management, which suggested that BUN levels might be a useful marker in this condition as well. To find out, the researchers analyzed data from 357 patients who were treated at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital emergency department and ultimately hospitalized for UGIB during 2004-2014.

The researchers analyzed BUN levels measured at admission and at the time closest to 24 hours after hospitalization, which ranged from 6 hours to 48 hours.

Thirty-seven patients (10%) experienced an increase in BUN level, while all the rest had levels that stayed steady or decreased. Those patients with BUN increases had a lower mean Glasgow-Blatchford score (7.8 vs. 9.6; P =.010), but there was no difference in AIMS65 scores.

Patients with BUN increases had greater odds of the composite outcome, which included inpatient death from any cause, inpatient rebleeding, a need for surgical or radiologic intervention, and/or a need for endoscopic reintervention during hospitalization (22% vs. 9%; P =.014). Inpatient mortality was higher in the increased BUN group (8% vs. 1%; P =.004).

Overall, BUN increase at 24 hours was associated with an odds ratio of 2.75 for the composite outcome (95% confidence interval, 1.13-6.70; P = .026).

A potential limitation to using the BUN is that it could just be catching patients with underlying renal disease. But when researchers adjusted for this, the odds ratio for increased BUN remained significant (OR, 3.00; P =.021).

“The nice part of the study is that it’s so easy to interpret and apply in a clinical setting. You just need two data points: BUN at presentation and at 24 hours. If the BUN level has risen, you need to have a higher degree of suspicion for the prognosis of those patients,” said Dr. Kumar.

The downside to BUN is that it doesn’t provide information for the first 24 hours. For that reason, BUN shouldn’t replace measures like the Glasgow-Blatchford score and the AIMS65 score. “But it’s very helpful to use this change in BUN score to get a sense of where the patient is trending. If it’s rising, there’s a higher risk of worse outcomes, and this could influence decisions about whether the patient should be in the ICU or the medical ward,” said Dr. Kumar.

In patients with acute nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (UGIB), increased blood urea nitrogen (BUN) levels at 24 hours were associated with worse outcomes. The marker, already proven useful in acute pancreatitis, could help physicians determine a patient’s prognosis.

Existing measures of UGIB risk are effective, but only about 30% of physicians ever calculate risk scores when evaluating UGIB patients, perhaps because they require measurements at multiple time points. “We personally think the reason for this is the busyness of clinical practices, especially the acute nature of upper GI bleeding. It’s often hard to step back to calculate a score that has multiple variables,” said study author Navin Kumar, MD, a fellow in gastroenterology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

The study was published in Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (2017. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.03.1533).

Like acute pancreatitis, upper GI bleeding requires resuscitation management, which suggested that BUN levels might be a useful marker in this condition as well. To find out, the researchers analyzed data from 357 patients who were treated at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital emergency department and ultimately hospitalized for UGIB during 2004-2014.

The researchers analyzed BUN levels measured at admission and at the time closest to 24 hours after hospitalization, which ranged from 6 hours to 48 hours.

Thirty-seven patients (10%) experienced an increase in BUN level, while all the rest had levels that stayed steady or decreased. Those patients with BUN increases had a lower mean Glasgow-Blatchford score (7.8 vs. 9.6; P =.010), but there was no difference in AIMS65 scores.

Patients with BUN increases had greater odds of the composite outcome, which included inpatient death from any cause, inpatient rebleeding, a need for surgical or radiologic intervention, and/or a need for endoscopic reintervention during hospitalization (22% vs. 9%; P =.014). Inpatient mortality was higher in the increased BUN group (8% vs. 1%; P =.004).

Overall, BUN increase at 24 hours was associated with an odds ratio of 2.75 for the composite outcome (95% confidence interval, 1.13-6.70; P = .026).

A potential limitation to using the BUN is that it could just be catching patients with underlying renal disease. But when researchers adjusted for this, the odds ratio for increased BUN remained significant (OR, 3.00; P =.021).

“The nice part of the study is that it’s so easy to interpret and apply in a clinical setting. You just need two data points: BUN at presentation and at 24 hours. If the BUN level has risen, you need to have a higher degree of suspicion for the prognosis of those patients,” said Dr. Kumar.

The downside to BUN is that it doesn’t provide information for the first 24 hours. For that reason, BUN shouldn’t replace measures like the Glasgow-Blatchford score and the AIMS65 score. “But it’s very helpful to use this change in BUN score to get a sense of where the patient is trending. If it’s rising, there’s a higher risk of worse outcomes, and this could influence decisions about whether the patient should be in the ICU or the medical ward,” said Dr. Kumar.

FROM GASTROINTESTINAL ENDOSCOPY

Key clinical point: BUN could be a useful prognostic marker.

Major finding: BUN increase indicated a threefold increased risk of poor outcomes.

Data source: Retrospective analysis of 357 patients at a single center.

Disclosures: The study did not receive external funding. Dr. Kumar reported having no financial disclosures.

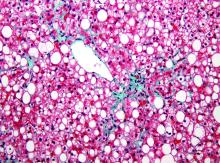

Liver disease likely to become increasing indication for bariatric surgery

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

AGA Resource

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides tools for gastroenterologists to lead a multidisciplinary team of health-care professionals for the management of patients with obesity. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

AGA Resource

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides tools for gastroenterologists to lead a multidisciplinary team of health-care professionals for the management of patients with obesity. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

PHILADELPHIA – There is a long list of benefits from bariatric surgery in the morbidly obese, but prevention of end-stage liver disease and the need for a first or second liver transplant is likely to grow as an indication, according to an overview of weight loss surgery at Digestive Diseases: New Advances, held by Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey, and Global Academy for Medical Education.

“Bariatric surgery is associated with significant improvement not just in diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and other complications of metabolic disorders but for me more interestingly, it is effective for treating fatty liver disease where you can see a 90% improvement in steatosis,” reported Subhashini Ayloo, MD, chief of minimally invasive robotic hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery and liver transplantation at New Jersey Medical School, Newark.

Trained in both bariatric surgery and liver transplant, Dr. Ayloo predicts that these fields will become increasingly connected because of the obesity epidemic and the related rise in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Dr. Ayloo reported that bariatric surgery is already being used in her center to avoid a second liver transplant in obese patients who are unable to lose sufficient weight to prevent progressive NAFLD after a first transplant.

The emphasis Dr. Ayloo placed on the role of bariatric surgery in preventing progression of NAFLD to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and the inflammatory process that leads to fibrosis, cirrhosis, and liver decompensation, was drawn from her interest in these two fields. However, she did not ignore the potential of protection from obesity control for other diseases.

“Obesity adversely affects every organ in the body,” Dr. Ayloo pointed out. As a result of weight loss achieved with bariatric surgery, there is now a large body of evidence supporting broad benefits, not just those related to fat deposited in hepatocytes.

“We have a couple of decades of experience that has been published [with bariatric surgery], and this has shown that it maintains weight loss long term, it improves all the obesity-associated comorbidities, and it is cost effective,” Dr. Ayloo said. Now with long-term follow-up, “all of the studies are showing that bariatric surgery improves survival.”

Although most of the survival data have been generated by retrospective cohort studies, Dr. Ayloo cited nine sets of data showing odds ratios associating bariatric surgery with up to a 90% reduction in death over periods of up to 10 years of follow-up. In a summary slide presented by Dr. Ayloo, the estimated mortality benefit over 5 years was listed as 85%. The same summary slide listed large improvements in relevant measures of morbidity for more than 10 organ systems, such as improvement or resolution of dyslipidemia and hypertension in the circulatory system, improvement or resolution of asthma and other diseases affecting the respiratory system, and resolution or improvement of gastroesophageal reflux disease and other diseases affecting the gastrointestinal system.

Specific to the liver, these benefits included a nearly 40% reduction in liver inflammation and 20% reduction in fibrosis. According to Dr. Ayloo, who noted that NAFLD is expected to overtake hepatitis C virus as the No. 1 cause of liver transplant within the next 5 years, these data are important for drawing attention to bariatric surgery as a strategy to control liver disease. She suggested that there is a need to create a tighter link between efforts to treat morbid obesity and advanced liver disease.

“There is an established literature showing that if somebody is morbidly obese, the rate of liver transplant is lower than when compared to patients with normal weight,” Dr. Ayloo said. “There is a call out in the transplant community that we need to address this and we cannot just be throwing this under the table.”

Because of the strong relationship between obesity and NAFLD, a systematic approach is needed to consider liver disease in obese patients and obesity in patients with liver disease, she said. The close relationship is relevant when planning interventions for either. Liver disease should be assessed prior to bariatric surgery regardless of the indication and then monitored closely as part of postoperative care, she said.

Dr. Ayloo identified weight control as an essential part of posttransplant care to prevent hepatic fat deposition that threatens transplant-free survival.

Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company. Dr. Ayloo reports no relevant financial relationships.

AGA Resource

The AGA Obesity Practice Guide provides tools for gastroenterologists to lead a multidisciplinary team of health-care professionals for the management of patients with obesity. Learn more at www.gastro.org/obesity.

AT DIGESTIVE DISEASES: NEW ADVANCES

AGA releases POWER – an obesity practice guide for gastroenterologists

The obesity epidemic has reached critical proportions. A new practice guide from the American Gastroenterological Association aims to help gastroenterologists engage in a multidisciplinary effort to tackle the problem.

The guide, entitled “POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources,” includes a comprehensive clinical process for assessing and safely and effectively managing patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on helping practitioners navigate the business operational issues related to the management of obesity. Both are in press for the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.023).

The POWER model recognizes obesity as an epidemic and as an economic and societal burden that should be embraced as a chronic, relapsing disease best managed across a flexible care cycle using a team approach.

“Every single gastroenterologist is at the front line of this obesity epidemic. Before patients develop diabetes or joint problems or cardiovascular disease, they are already in our clinics, they already have [gastroesophageal reflux disease], they have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, they have colon cancer – and those conditions present even earlier than the other complications of obesity,” said Dr. Acosta of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The guide is a model for addressing obesity – the root cause of many of these conditions – rather than simply treating its symptoms, he added.

The approach to obesity management promoted by POWER involves four phases along a continuum of care: assessment, intensive weight loss intervention, weight stabilization and reintensification when needed, and prevention of weight regain.

Lifestyle changes are the cornerstones of obesity management and maintenance of weight loss, but the POWER model includes much more, as it incorporates guidance on the use of pharmacotherapy, bariatric endoscopy, and surgery.

“We tried to make it extremely simple, bringing it down to the busy clinician level,” Dr. Acosta said. “We want to be able to embrace and tackle obesity... in a very straightforward manner.”

Gastroenterologists shouldn’t be afraid of taking on obesity, he added.

“We feel comfortable managing extremely complicated medications, so we should be able to handle the obesity medications. We are already endoscopists... so we want all gastroenterologists to say, ‘I can do this, too; I can incorporate this into my practice,’ ” he said.

Further, gastroenterologists already have a relationship with bariatric surgeons, so referring those with obesity for surgery if appropriate is also simple, he added.

When it comes to moving through the four phases of care, each should be addressed separately using the best evidence available. Realistic goals should be set, and only when those goals are met should care move to the next phase, according to the guide. Learn how to implement the AGA Obesity Practice Guide at www.gastro.org/obesity.

The assessment phase should include a medical evaluation to identify underlying etiologies, screen for causes of secondary weight gain, and identify related comorbidities. A nutrition evaluation should focus not only on nutritional status and appetite, but also on the patient’s relationship with food, food allergies and intolerances, and food environment. A physical activity/exercise evaluation should explore the patient’s activity level and preferences, as well as limiting factors such as joint disease.

A psychosocial evaluation is particularly important, as behavioral modification is a critical component of successful obesity management, and some patients – such as those with a low score on the weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire Short-Form – may benefit from referral to a health care professional experienced in obesity counseling and behavioral therapy.

Gastroenterologists already work with other specialists, including nutritionists, psychiatrists, and psychologists within their institutions and communities, so the POWER model is an extension of that.

“That’s what this proposes – a multidisciplinary team effort,” he said.

The approach to treatment should be based on the findings of these assessments.

“Physicians should discuss all the appropriate options and their expected weight loss, potential side effects, and figure in the patient’s wishes and goals. Furthermore, physicians should recognize special comorbidities that may favor one intervention over another,” the authors wrote.

The intensive weight loss intervention phase should be based on modest initial weight loss goals, which increase the likelihood of success, increase patient confidence, and encourage ongoing efforts to lose weight. Further, modest weight loss vs. larger amounts of weight loss is more easily achieved and maintained. In addition to lifestyle changes, an evaluation of whether other interventions are needed is important, particularly in patients with weight regain or plateaus in weight loss.

The weight stabilization and intensification therapy for relapse phase is essential to prevent weight regain and its associated consequences. This phase introduces patients to the attitudes and behaviors that are likely to lead to long-term maintenance of weight loss, the authors note.

The prevention of weight regain phase – a maintenance phase – is unique among obesity care guidelines, and is a critical component of obesity management, Dr. Acosta said.

“Helping patients lose weight and keep it off requires a comprehensive and sustained effort that involves devising an individualized approach to diet, behavior, and exercise,” he and his colleagues wrote.

In addition to detailed steps and tips for moving through this care cycle, the POWER guide also details the various tools to facilitate adherence to a healthier diet and lifestyle. Various medications, including phentermine, extended-release phentermine/topiramate, lorcaserin, and liraglutide are described, as are various types of bariatric endoscopy and bariatric surgery.

A section on addressing the unique needs of obese children and adolescents is also included in the guide for those gastroenterologists who treat children.

“Obesity really begins in childhood, so it is a pediatric disease in its origin, so it was important to us to incorporate issues unique to children for our pediatric GI colleagues,” Dr. Streett said.

Importantly, the practice guide was developed with input from the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, The Obesity Society, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. and the program has been endorsed with additional input by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the Obesity Medicine Association.

This collaborative approach is also unique among existing guidelines, and is important, given the need for practitioners across the care spectrum to work together to address obesity, she said.

“What we’ve been doing [individually] hasn’t worked successfully, so that is something that people recognize in the field of medicine: Obesity is something that has physiological, nutritional, dietetic, socioeconomic, and behavioral aspects and we need to have a multipronged approach for success. We need patients to be hearing similar messages and having their care integrated,” she said, adding that “as we move toward a value-based schema, this is the perfect disorder to address in that way.”

Dr. Acosta is a stockholder of Gila Therapeutics and serves on the scientific advisory board or board of directors of Gila Therapeutics, Inversago, and General Mills. Dr. Streett reported having no disclosures.

The obesity epidemic has reached critical proportions. A new practice guide from the American Gastroenterological Association aims to help gastroenterologists engage in a multidisciplinary effort to tackle the problem.

The guide, entitled “POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources,” includes a comprehensive clinical process for assessing and safely and effectively managing patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on helping practitioners navigate the business operational issues related to the management of obesity. Both are in press for the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.023).

The POWER model recognizes obesity as an epidemic and as an economic and societal burden that should be embraced as a chronic, relapsing disease best managed across a flexible care cycle using a team approach.

“Every single gastroenterologist is at the front line of this obesity epidemic. Before patients develop diabetes or joint problems or cardiovascular disease, they are already in our clinics, they already have [gastroesophageal reflux disease], they have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, they have colon cancer – and those conditions present even earlier than the other complications of obesity,” said Dr. Acosta of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The guide is a model for addressing obesity – the root cause of many of these conditions – rather than simply treating its symptoms, he added.

The approach to obesity management promoted by POWER involves four phases along a continuum of care: assessment, intensive weight loss intervention, weight stabilization and reintensification when needed, and prevention of weight regain.

Lifestyle changes are the cornerstones of obesity management and maintenance of weight loss, but the POWER model includes much more, as it incorporates guidance on the use of pharmacotherapy, bariatric endoscopy, and surgery.

“We tried to make it extremely simple, bringing it down to the busy clinician level,” Dr. Acosta said. “We want to be able to embrace and tackle obesity... in a very straightforward manner.”

Gastroenterologists shouldn’t be afraid of taking on obesity, he added.

“We feel comfortable managing extremely complicated medications, so we should be able to handle the obesity medications. We are already endoscopists... so we want all gastroenterologists to say, ‘I can do this, too; I can incorporate this into my practice,’ ” he said.

Further, gastroenterologists already have a relationship with bariatric surgeons, so referring those with obesity for surgery if appropriate is also simple, he added.

When it comes to moving through the four phases of care, each should be addressed separately using the best evidence available. Realistic goals should be set, and only when those goals are met should care move to the next phase, according to the guide. Learn how to implement the AGA Obesity Practice Guide at www.gastro.org/obesity.

The assessment phase should include a medical evaluation to identify underlying etiologies, screen for causes of secondary weight gain, and identify related comorbidities. A nutrition evaluation should focus not only on nutritional status and appetite, but also on the patient’s relationship with food, food allergies and intolerances, and food environment. A physical activity/exercise evaluation should explore the patient’s activity level and preferences, as well as limiting factors such as joint disease.

A psychosocial evaluation is particularly important, as behavioral modification is a critical component of successful obesity management, and some patients – such as those with a low score on the weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire Short-Form – may benefit from referral to a health care professional experienced in obesity counseling and behavioral therapy.

Gastroenterologists already work with other specialists, including nutritionists, psychiatrists, and psychologists within their institutions and communities, so the POWER model is an extension of that.

“That’s what this proposes – a multidisciplinary team effort,” he said.

The approach to treatment should be based on the findings of these assessments.

“Physicians should discuss all the appropriate options and their expected weight loss, potential side effects, and figure in the patient’s wishes and goals. Furthermore, physicians should recognize special comorbidities that may favor one intervention over another,” the authors wrote.

The intensive weight loss intervention phase should be based on modest initial weight loss goals, which increase the likelihood of success, increase patient confidence, and encourage ongoing efforts to lose weight. Further, modest weight loss vs. larger amounts of weight loss is more easily achieved and maintained. In addition to lifestyle changes, an evaluation of whether other interventions are needed is important, particularly in patients with weight regain or plateaus in weight loss.

The weight stabilization and intensification therapy for relapse phase is essential to prevent weight regain and its associated consequences. This phase introduces patients to the attitudes and behaviors that are likely to lead to long-term maintenance of weight loss, the authors note.

The prevention of weight regain phase – a maintenance phase – is unique among obesity care guidelines, and is a critical component of obesity management, Dr. Acosta said.

“Helping patients lose weight and keep it off requires a comprehensive and sustained effort that involves devising an individualized approach to diet, behavior, and exercise,” he and his colleagues wrote.

In addition to detailed steps and tips for moving through this care cycle, the POWER guide also details the various tools to facilitate adherence to a healthier diet and lifestyle. Various medications, including phentermine, extended-release phentermine/topiramate, lorcaserin, and liraglutide are described, as are various types of bariatric endoscopy and bariatric surgery.

A section on addressing the unique needs of obese children and adolescents is also included in the guide for those gastroenterologists who treat children.

“Obesity really begins in childhood, so it is a pediatric disease in its origin, so it was important to us to incorporate issues unique to children for our pediatric GI colleagues,” Dr. Streett said.

Importantly, the practice guide was developed with input from the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, The Obesity Society, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. and the program has been endorsed with additional input by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the Obesity Medicine Association.

This collaborative approach is also unique among existing guidelines, and is important, given the need for practitioners across the care spectrum to work together to address obesity, she said.

“What we’ve been doing [individually] hasn’t worked successfully, so that is something that people recognize in the field of medicine: Obesity is something that has physiological, nutritional, dietetic, socioeconomic, and behavioral aspects and we need to have a multipronged approach for success. We need patients to be hearing similar messages and having their care integrated,” she said, adding that “as we move toward a value-based schema, this is the perfect disorder to address in that way.”

Dr. Acosta is a stockholder of Gila Therapeutics and serves on the scientific advisory board or board of directors of Gila Therapeutics, Inversago, and General Mills. Dr. Streett reported having no disclosures.

The obesity epidemic has reached critical proportions. A new practice guide from the American Gastroenterological Association aims to help gastroenterologists engage in a multidisciplinary effort to tackle the problem.

The guide, entitled “POWER: Practice Guide on Obesity and Weight Management, Education and Resources,” includes a comprehensive clinical process for assessing and safely and effectively managing patients with obesity, as well as a framework focused on helping practitioners navigate the business operational issues related to the management of obesity. Both are in press for the May issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (2016. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.023).

The POWER model recognizes obesity as an epidemic and as an economic and societal burden that should be embraced as a chronic, relapsing disease best managed across a flexible care cycle using a team approach.

“Every single gastroenterologist is at the front line of this obesity epidemic. Before patients develop diabetes or joint problems or cardiovascular disease, they are already in our clinics, they already have [gastroesophageal reflux disease], they have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, they have colon cancer – and those conditions present even earlier than the other complications of obesity,” said Dr. Acosta of the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn.

The guide is a model for addressing obesity – the root cause of many of these conditions – rather than simply treating its symptoms, he added.

The approach to obesity management promoted by POWER involves four phases along a continuum of care: assessment, intensive weight loss intervention, weight stabilization and reintensification when needed, and prevention of weight regain.

Lifestyle changes are the cornerstones of obesity management and maintenance of weight loss, but the POWER model includes much more, as it incorporates guidance on the use of pharmacotherapy, bariatric endoscopy, and surgery.

“We tried to make it extremely simple, bringing it down to the busy clinician level,” Dr. Acosta said. “We want to be able to embrace and tackle obesity... in a very straightforward manner.”

Gastroenterologists shouldn’t be afraid of taking on obesity, he added.

“We feel comfortable managing extremely complicated medications, so we should be able to handle the obesity medications. We are already endoscopists... so we want all gastroenterologists to say, ‘I can do this, too; I can incorporate this into my practice,’ ” he said.

Further, gastroenterologists already have a relationship with bariatric surgeons, so referring those with obesity for surgery if appropriate is also simple, he added.

When it comes to moving through the four phases of care, each should be addressed separately using the best evidence available. Realistic goals should be set, and only when those goals are met should care move to the next phase, according to the guide. Learn how to implement the AGA Obesity Practice Guide at www.gastro.org/obesity.

The assessment phase should include a medical evaluation to identify underlying etiologies, screen for causes of secondary weight gain, and identify related comorbidities. A nutrition evaluation should focus not only on nutritional status and appetite, but also on the patient’s relationship with food, food allergies and intolerances, and food environment. A physical activity/exercise evaluation should explore the patient’s activity level and preferences, as well as limiting factors such as joint disease.

A psychosocial evaluation is particularly important, as behavioral modification is a critical component of successful obesity management, and some patients – such as those with a low score on the weight Efficacy Lifestyle Questionnaire Short-Form – may benefit from referral to a health care professional experienced in obesity counseling and behavioral therapy.

Gastroenterologists already work with other specialists, including nutritionists, psychiatrists, and psychologists within their institutions and communities, so the POWER model is an extension of that.

“That’s what this proposes – a multidisciplinary team effort,” he said.

The approach to treatment should be based on the findings of these assessments.

“Physicians should discuss all the appropriate options and their expected weight loss, potential side effects, and figure in the patient’s wishes and goals. Furthermore, physicians should recognize special comorbidities that may favor one intervention over another,” the authors wrote.

The intensive weight loss intervention phase should be based on modest initial weight loss goals, which increase the likelihood of success, increase patient confidence, and encourage ongoing efforts to lose weight. Further, modest weight loss vs. larger amounts of weight loss is more easily achieved and maintained. In addition to lifestyle changes, an evaluation of whether other interventions are needed is important, particularly in patients with weight regain or plateaus in weight loss.

The weight stabilization and intensification therapy for relapse phase is essential to prevent weight regain and its associated consequences. This phase introduces patients to the attitudes and behaviors that are likely to lead to long-term maintenance of weight loss, the authors note.

The prevention of weight regain phase – a maintenance phase – is unique among obesity care guidelines, and is a critical component of obesity management, Dr. Acosta said.

“Helping patients lose weight and keep it off requires a comprehensive and sustained effort that involves devising an individualized approach to diet, behavior, and exercise,” he and his colleagues wrote.

In addition to detailed steps and tips for moving through this care cycle, the POWER guide also details the various tools to facilitate adherence to a healthier diet and lifestyle. Various medications, including phentermine, extended-release phentermine/topiramate, lorcaserin, and liraglutide are described, as are various types of bariatric endoscopy and bariatric surgery.

A section on addressing the unique needs of obese children and adolescents is also included in the guide for those gastroenterologists who treat children.

“Obesity really begins in childhood, so it is a pediatric disease in its origin, so it was important to us to incorporate issues unique to children for our pediatric GI colleagues,” Dr. Streett said.

Importantly, the practice guide was developed with input from the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, The Obesity Society, the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, and the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. and the program has been endorsed with additional input by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, and the Obesity Medicine Association.

This collaborative approach is also unique among existing guidelines, and is important, given the need for practitioners across the care spectrum to work together to address obesity, she said.

“What we’ve been doing [individually] hasn’t worked successfully, so that is something that people recognize in the field of medicine: Obesity is something that has physiological, nutritional, dietetic, socioeconomic, and behavioral aspects and we need to have a multipronged approach for success. We need patients to be hearing similar messages and having their care integrated,” she said, adding that “as we move toward a value-based schema, this is the perfect disorder to address in that way.”

Dr. Acosta is a stockholder of Gila Therapeutics and serves on the scientific advisory board or board of directors of Gila Therapeutics, Inversago, and General Mills. Dr. Streett reported having no disclosures.

South dominates rankings of most obese U.S. cities

Jackson, Miss., is the most obese city in the United States for 2017, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The city topped the ranking of the 100 heaviest metro areas in the country with a score of 84.9 out of a possible 100 points based on 17 key metrics in three broad categories: obese and overweight people (50 points), weight-related health problems (30 points), and health environment (20 points), according to WalletHub.

The second-most obese city for 2017 is Memphis, with Little Rock, Ark.; McAllen, Tex.; and Shreveport, La., occupying the rest of the top five. All of the cities in the top 10 – all of the cities in the top 20, actually – are located in the South, with the first non–Southern city (Indianapolis) making its appearance at number 21, the WalletHub analysis shows. At number 100 in the rankings is Seattle/Tacoma.

Data for the analysis came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, County Health Rankings, the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, the Trust for America’s Health, and WalletHub’s own research, including its report Best & Worst Cities for an Active Lifestyle.

Jackson, Miss., is the most obese city in the United States for 2017, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The city topped the ranking of the 100 heaviest metro areas in the country with a score of 84.9 out of a possible 100 points based on 17 key metrics in three broad categories: obese and overweight people (50 points), weight-related health problems (30 points), and health environment (20 points), according to WalletHub.

The second-most obese city for 2017 is Memphis, with Little Rock, Ark.; McAllen, Tex.; and Shreveport, La., occupying the rest of the top five. All of the cities in the top 10 – all of the cities in the top 20, actually – are located in the South, with the first non–Southern city (Indianapolis) making its appearance at number 21, the WalletHub analysis shows. At number 100 in the rankings is Seattle/Tacoma.

Data for the analysis came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, County Health Rankings, the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, the Trust for America’s Health, and WalletHub’s own research, including its report Best & Worst Cities for an Active Lifestyle.

Jackson, Miss., is the most obese city in the United States for 2017, according to the personal finance website WalletHub.

The city topped the ranking of the 100 heaviest metro areas in the country with a score of 84.9 out of a possible 100 points based on 17 key metrics in three broad categories: obese and overweight people (50 points), weight-related health problems (30 points), and health environment (20 points), according to WalletHub.

The second-most obese city for 2017 is Memphis, with Little Rock, Ark.; McAllen, Tex.; and Shreveport, La., occupying the rest of the top five. All of the cities in the top 10 – all of the cities in the top 20, actually – are located in the South, with the first non–Southern city (Indianapolis) making its appearance at number 21, the WalletHub analysis shows. At number 100 in the rankings is Seattle/Tacoma.

Data for the analysis came from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, County Health Rankings, the Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service, the Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative, the Trust for America’s Health, and WalletHub’s own research, including its report Best & Worst Cities for an Active Lifestyle.

Open-capsule PPIs linked to faster ulcer healing after Roux-en-Y

The use of proton pump inhibitors in opened instead of closed capsules was associated with a nearly fourfold shorter median healing time among patients who developed marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, in a single-center retrospective cohort study.

In contrast, the specific class of proton pump inhibitor (PPI) did not affect healing times, wrote Allison R. Schulman, MD, and her associates at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. The report is in the April issue of Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology (doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.015). “Given these results and the high prevalence of marginal ulceration in this patient population, further study in a randomized controlled setting is warranted, and use of open-capsule PPIs should be considered as a low-risk, low-cost alternative,” they added.

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is one of the most common types of gastric bypass surgeries in the world, and up to 16% of patients develop postsurgical ulcers at the gastrojejunal anastomosis, the investigators noted. Acidity is a prime suspect in these “marginal ulcerations” because bypassing the acid-buffering duodenum exposes the jejunum to acid from the stomach, they added. High-dose PPIs are the main treatment, but there is no consensus on the formulation or dose of therapy. Because Roux-en-Y creates a small gastric pouch and hastens small-bowel transit, closed capsules designed to break down in the stomach “even may make their way to the colon before breakdown occurs,” they wrote.

They reviewed medical charts from patients who developed marginal ulcerations after undergoing Roux-en-Y gastric bypass at their hospital from 2000 through 2015. A total of 115 patients received open-capsule PPIs and 49 received intact capsules. All were followed until their ulcers healed.

For the open-capsule group, median time to healing was 91 days, compared with 342 days for the closed-capsule group (P less than .001). Importantly, capsule type was the only independent predictor of healing time (hazard ratio, 6.0; 95% confidence interval, 3.7 to 9.8; P less than .001) in a Cox regression model that included other known correlates of ulcer healing, including age, smoking status, the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, Helicobacter pylori infection, the length of the gastric pouch, and the presence of fistulae or foreign bodies such as sutures or staples.

The use of sucralfate also did not affect time to ulcer healing, reflecting “many previous studies showing a lack of definitive benefit to this medication,” the researchers said. The findings have “tremendous implications” for health care utilization, they added. Indeed, patients who received open-capsule PPIs needed significantly fewer endoscopic procedures (median, 1.2 versus 1.8; P = .02) and used fewer health care resources overall ($7,206 versus $11,009; P = .05) compared with those prescribed intact PPI capsules.

This study was limited to patients who developed ulcer symptoms and underwent repeated surveillance endoscopies after surgery, the researchers noted. Selection bias is always a concern with retrospective studies, but insurers always covered both types of therapy and the choice of capsule type was entirely up to providers, all of whom consistently prescribed either open- or closed-capsule PPI therapy, they added.

The investigators did not acknowledge external funding sources. Dr. Schulman and four coinvestigators reported having no competing interests. One coinvestigator disclosed ties to Olympus, Boston Scientific, and Covidien.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) are frequently employed to treat marginal ulcers after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB). In a retrospective study, Schulman et al. compared intact vs. “open” PPI capsules.

They state that “this may be overcome by use of a soluble form of PPI,” but don’t state what is meant by “soluble PPI” or how the open-capsule PPI was delivered. Among the PPIs they reported using to compare intact vs. open capsules was Protonix [pantoprazole] which is not produced as a capsule, and soluble Prevacid [lansoprazole], which is an orally disintegrating tablet that should provide characteristics similar to an “open capsule.”