User login

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

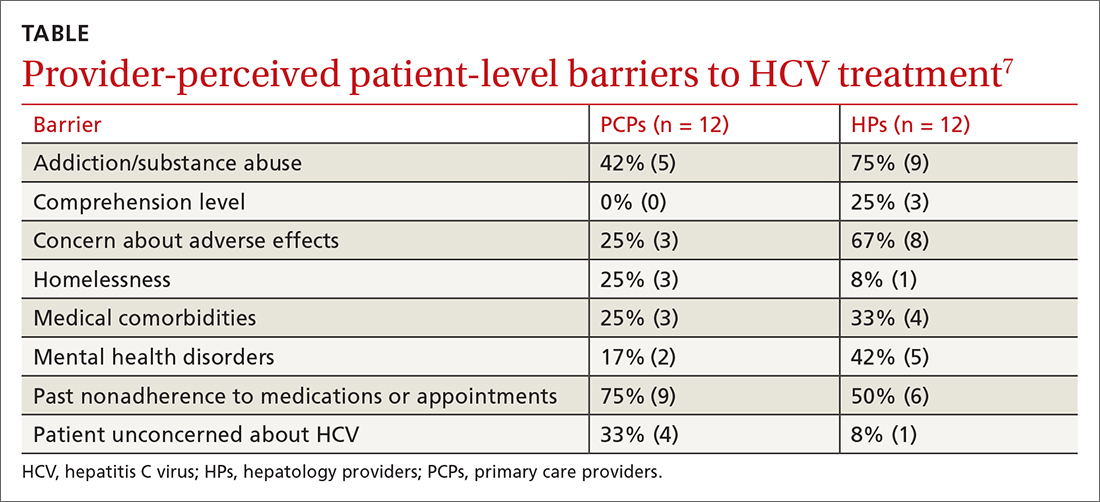

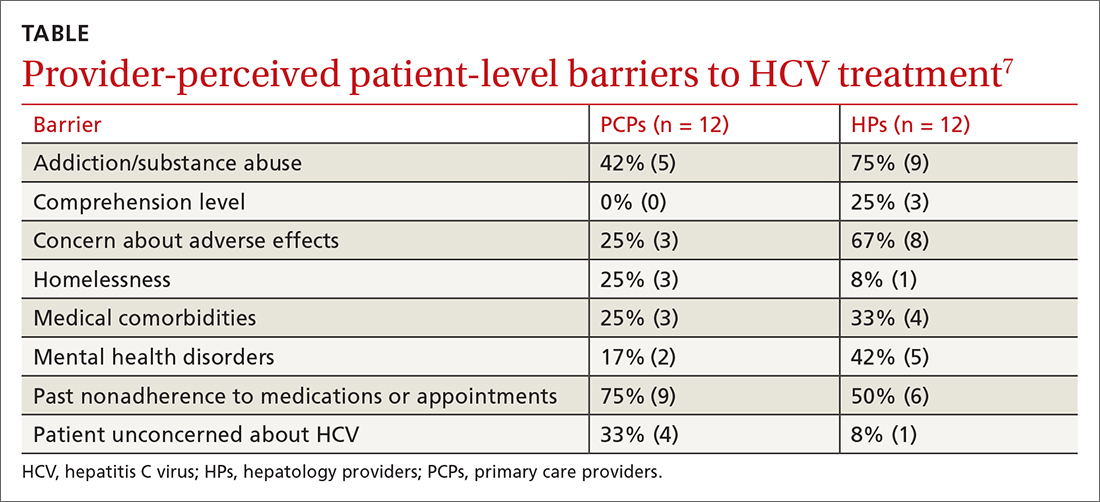

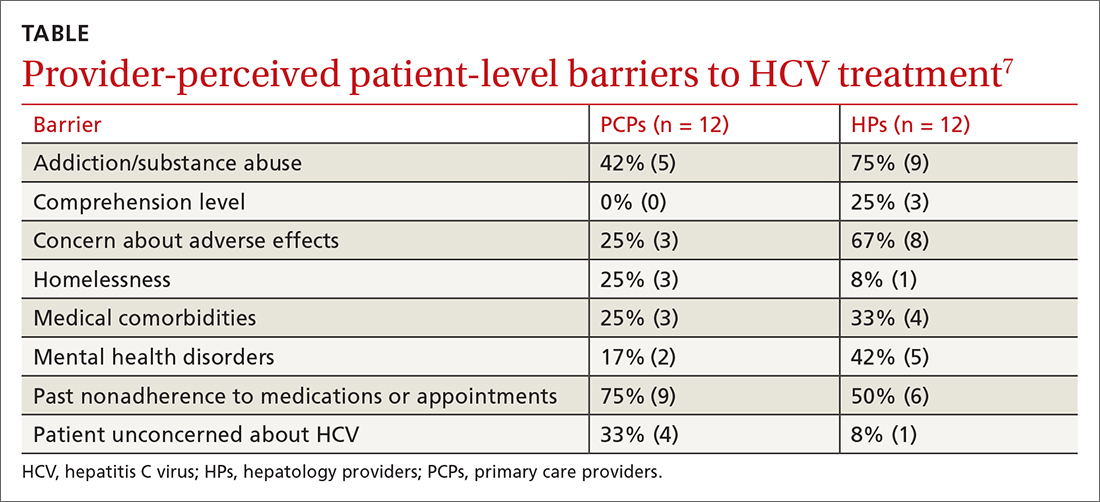

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Race, gender, and other factors are associated with lack of HCV Tx

A retrospective study (N = 894) assessed factors associated with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) initiation.1 Patients who were HCV+ with at least 1 clinical visit during the study period completed a survey of psychological, behavioral, and social life assessments. The final cohort (57% male; 64% ≥ 61 years old) was divided into patients who initiated DAA treatment (n = 690) and those who did not (n = 204).

In an adjusted multivariable analysis, factors associated with lower odds of DAA initiation included Black race (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.59 vs White race; 95% CI, 0.36-0.98); perceived difficulty accessing medical care (aOR = 0.48 vs no difficulty; 95% CI, 0.27-0.83); recent intravenous (IV) drug use (aOR = 0.11 vs no use; 95% CI, 0.02-0.54); alcohol use disorder (AUD; aOR = 0.58 vs no AUD; 95% CI, 0.38-0.90); severe depression (aOR = 0.42 vs no depression; 95% CI, 0.2-0.9); recent homelessness (aOR = 0.36 vs no homelessness; 95% CI, 0.14-0.94); and recent incarceration (aOR = 0.34 vs no incarceration; 95% CI, 0.12-0.94).1

A multicenter, observational prospective cohort study (N = 3075) evaluated receipt of HCV treatment for patients co-infected with HCV and HIV.2 The primary outcome was initiation of HCV treatment with DAAs; 1957 patients initiated therapy, while 1118 did not. Significant independent risk factors for noninitiation of treatment included age younger than 50 years, a history of IV drug use, and use of opioid substitution therapy (OST). Other factors included psychiatric comorbidity (odds ratio [OR] = 0.45; 95% CI, 0.27-0.75), incarceration (OR = 0.6; 95% CI, 0.43-0.87), and female gender (OR = 0.80; 95% CI, 0.66-0.98). In a multivariate analysis limited to those with a history of IV drug use, both use of OST (aOR = 0.55; 95% CI, 0.40-0.75) and recent IV drug use (aOR = 0.019; 95% CI, 0.004-0.087) were identified as factors with low odds of treatment implementation.2

A retrospective cohort study (N = 1024) of medical charts examined the barriers to treatment in adults with chronic HCV infection.3 Of the patient population, 208 were treated and 816 were untreated. Patients not receiving DAAs were associated with poor adherence to/loss to follow-up (n = 548; OR = 36.6; 95% CI, 19.6-68.4); significant psychiatric illness (n = 103; OR = 2.02; 95% CI, 1.13-3.71); and coinfection with HIV (n = 188; OR = 4.5; 95% CI, 2.5-8.2).3

A German multicenter retrospective case-control study (N = 793) identified factors in patient and physician decisions to initiate treatment for HCV.4 Patients were ≥ 18 years old, confirmed to be HCV+, and had visited their physician at least 1 time during the observation period. A total of 573 patients received treatment and 220 did not. Patients and clinicians of those who chose not to receive treatment completed a survey that collected reasons for not treating. The most prevalent reason for not initiating treatment was patient wish (42%). This was further delineated to reveal that 17.3% attributed their decision to fear of treatment and 13.2% to fear of adverse events. Other factors associated with nontreatment included IV drug use (aOR = 0.31; 95% CI, 0.16-0.62); HIV coinfection (aOR = 0.19; 95% CI, 0.09-0.40); and use of OST (aOR = 0.37; 95% CI, 0.21-0.68). Patient demographics associated with wish not to be treated included older age (20.2% of those ≥ 40 years old vs 6.4% of those < 40 years old; P = .03) and female gender (51.0% of females vs 35.2% of males; P = .019).4

An analysis of a French insurance database (N = 22,545) evaluated the incidence of HCV treatment with DAAs in patients who inject drugs (PWID) with a diagnosis of alcohol use disorder (AUD).5 All participants (78% male; median age, 49 years) were chronically HCV-infected and covered by national health insurance. Individuals were grouped by AUD status: untreated (n = 5176), treated (n = 3020), and no AUD (n = 14349). After multivariate adjustment, those with untreated AUD had lower uptake of DAAs than those who did not have AUD (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR] = 0.86; 95% CI, 0.78-0.94) and those with treated AUD (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.74-0.94). There were no differences between those with treated AUD and those who did not have AUD. Other factors associated with lower DAA uptake were access to care (aHR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.83-0.98) and female gender (aHR = 0.83; 95% CI, 0.76-0.9).5

A 2017 retrospective cohort study evaluated predictors and barriers to follow-up and treatment with DAAs among veterans who were HCV+.6 Patients (94% > 50 years old; 97% male; 48% white) had established HCV care within the US Department of Veterans Affairs system. Of those who followed up with at least 1 visit to an HCV specialty clinic (n = 47,165), 29% received DAAs. Factors associated with lack of treatment included race (Black vs White: OR = 0.77; 95% CI, 0.72-0.82; Hispanic vs White: OR = 0.88; 95% CI, 0.79-0.97); IV drug use (OR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.80-0.88); AUD (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.70-0.77); medical comorbidities (OR = 0.71; 95% CI, 0.66-0.77); and hepatocellular carcinoma (OR = 0.73; 95% CI, 0.65-0.83).6

Continue to: Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

Providers identify similar barriers to treatment of HCV

A 2017 prospective qualitative study (N = 24) from a Veterans Affairs health care system analyzed provider-perceived barriers to initiation of and adherence to HCV treatment.7 The analysis focused on differences by provider specialty. Primary care providers (PCPs; n = 12; 17% with > 40 patients with HCV) and hepatology providers (HPs; n = 12; 83% with > 40 patients with HCV) participated in a semi-structured telephone-based interview, providing their perceptions of patient-level barriers to HCV treatment. Eight patient-level barrier themes were identified; these are outlined in the TABLE7 along with data for both PCPs and HPs.

Editor’s takeaway

These 7 cohort studies show us the factors we consider and the reasons we give to not initiate HCV treatment. Some of the factors seem reasonable, but many do not. We might use this list to remind and challenge ourselves to work through barriers to provide the best possible treatment.

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

1. Spradling PR, Zhong Y, Moorman AC, et al. Psychosocial obstacles to hepatitis C treatment initiation among patients in care: a hitch in the cascade of cure. Hepatol Commun. 2021;5:400-411. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1632

2. Rivero-Juarez A, Tellez F, Castano-Carracedo M, et al. Parenteral drug use as the main barrier to hepatitis C treatment uptake in HIV-infected patients. HIV Medicine. 2019;20:359-367. doi: 10.1111/hiv.12715

3. Al-Khazraji A, Patel I, Saleh M, et al. Identifying barriers to the treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. Dig Dis. 2020;38:46-52. doi: 10.1159/000501821

4. Buggisch P, Heiken H, Mauss S, et al. Barriers to initiation of hepatitis C virus therapy in Germany: a retrospective, case-controlled study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:3p250833. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250833

5. Barré T, Marcellin F, Di Beo V, et al. Untreated alcohol use disorder in people who inject drugs (PWID) in France: a major barrier to HCV treatment uptake (the ANRS-FANTASIO study). Addiction. 2019;115:573-582. doi: 10.1111/add.14820

6. Lin M, Kramer J, White D, et al. Barriers to hepatitis C treatment in the era of direct acting antiviral agents. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;46:992-1000. doi: 10.1111/apt.14328

7. Rogal SS, McCarthy R, Reid A, et al. Primary care and hepatology provider-perceived barriers to and facilitators of hepatitis C treatment candidacy and adherence. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:1933-1943. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4608-9

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Multiple patient-specific and provider-perceived factors delay initiation of treatment in patients with hepatitis C. Patient-specific barriers to initiation of treatment for hepatitis C virus (HCV) include age, race, gender, economic status, insurance status, and comorbidities such as HIV coinfection, psychiatric illness, and other psychosocial factors.

Provider-perceived patient factors include substance abuse history, older age, psychiatric illness, medical comorbidities, treatment adverse effect risks, and factors that might limit adherence (eg, comprehension level).

Study limitations included problems with generalizability of the populations studied and variability in reporting or interpreting data associated with substance or alcohol use disorders