User login

- Building strong relationships among physicians and staff improves the practice’s ability to deal with the uncertainties of a rapidly changing environment (B).

- Interacting proactively with the economic, social, political, and cultural environment—the practice landscape—provides opportunities for adaptation and ongoing learning (C).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

“Everyday Primary Care,” a popular, urban 3-physician family medicine office, has served mostly middle- and working-class people for more than 25 years. Most of the patients have grown older with Drs. Newman and Cope and now have a substantial chronic disease burden. Dr. Varimore, Dr. Cope’s son, has recently joined the practice. He replaced a long-time partner who left in frustration to do emergency medicine.

On a typical day, Dr. Cope enters the crowded waiting room, sighs, and walks quickly toward the nurses’ station where her third scheduled patient has just arrived; her first 2 patients are already waiting in examining rooms. In her tiny office, stacks of charts, phone messages, and forms await her attention. Phones ring constantly. Rushing to see her first patient, Dr. Cope squeezes past her nursing assistant in the narrow hallway. She catches a glimpse of her partner, Dr. Newman, at the end of the corridor. They grunt a word of greeting, but say nothing more. In fact, the physicians and their staff have barely spoken to each other in days.

The 2 older physicians were hopeful that Dr. Varimore would infuse fresh energy into the practice, but the only thing that has changed with his arrival is an increase in the number of patients they see and the expenses of running the office. When the door finally closes at the end of a long day, everyone leaves feeling exhausted and alone.

A toxic atmosphere

The situation at Everyday Primary Care is not unusual.1 These are unhealthy times for most primary care practices. Despite the critical role that primary care is expected to play in health care reform, there is tremendous uncertainty about the future viability of primary care practice.1-6 An alarming number of primary care physicians are leaving practice or taking early retirement as frustration and exhaustion move deeply into our community.1,7,8 Staff turnover is high and disruptive. Primary care physicians feel buffeted by conflicting patient demands, insurance coverage restrictions, inadequate Medicare reimbursement, multiple and often inconsistent practice guidelines, and onerous government regulations. Primary care practices suffer from a culture of despair that impedes decision-making. These practices—and the physicians who struggle to keep them viable—need to develop resilience to survive in this hostile climate and improve the quality of care they provide.

Research-based strategies. This article suggests strategies for primary care practices to move forward—whatever proposed reforms emerge from the current debate. The strategies we propose derive from specific, concrete observations gathered during a 15-year program of research that included nearly 500 primary care offices.9-16 (In fact, Everyday Primary Care is an actual practice that participated in 1 of our studies, though we’ve changed its name and the names of the physicians.) Our research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and included both descriptive and intervention projects. Our studies provided in-depth descriptions of a wide variety of primary care practices, as well as new models for describing change.10,14,15 The practices varied in how they delivered preventive services, in their cancer-related prevention and screening activities, and in the way they managed chronic disease.11,14,17-19 Yet across all these variations, we found a pattern in which educated, well-trained professionals and staff wanted to provide good care, but found themselves thwarted in their efforts to succeed.

What’s going on here? We sought to understand what was really happening in these primary care practices and to formulate strategies to help them become better for patients, staff, and clinicians.

We came up with 2 fundamental insights:

- Practices that focus on building strong internal relationships are better able to deal with surprise and uncertainty.

- Practices that are proactive in interacting with the changing environment will find multiple ways to achieve effective health care delivery.

Work on building those relationships

In our research, we repeatedly observed that careful attention to the relationships among all the people (clinical and nonclinical staff) working within each practice is critical to improving practice processes and outcomes.20 We wanted to learn why relationships mattered so much and how they could be improved. What we found can best be explained by taking another look at Everyday Primary Care.

The physician-owners of everyday Primary Care, feeling stressed out and recognizing that “things are not good here,” signed up to participate in 1 of our studies. Participation required allowing an outside facilitator to observe practice operations and conduct open-ended interviews with physicians and staff over a 2-week period, followed by a series of 12 weekly meetings. In addition, physicians and staff agreed to fill out multiple surveys during the study process and allow researchers to audit the charts of randomly selected patient samples.

One year after Everyday Primary Care signed up, the office space was still cramped, the financial situation was no better, and environmental pressures were continuing to mount. And yet, the practice felt like a different place, one filled with energy and hope. What had happened?

RAP, huddles, effective teams. Most importantly, the quality and types of relationships within the practice had changed. At our suggestion, the practice formed a RAP (reflective adaptive process) team under the guidance of a facilitator—a nurse we trained in basic facilitation skills, including effective meeting strategies, brainstorming, and conflict resolution. The team consisted of physician leaders (both Drs. Cope and Varimore attended all meetings), the practice manager, representatives from each part of the practice (billing, front desk, nursing staff, insurance clerk), and a patient.15 The RAP intervention was designed to provide members with time and space to reflect and opportunities to learn the value of communication, respectful interaction, and listening to diverse opinions and perspectives.20 The team met with the facilitator for 1 hour every week, reviewed the practice’s vision, and developed and implemented strategies for solving prioritized practice issues and problems.

Brainstorming helped identify recurrent problems. As the RAP meetings progressed, it became clear that despite the close quarters, each part of the practice was isolated from the others and all team members were frustrated by their inability to influence the lead physician, Dr. Cope. Over time, the RAP meetings changed the relationship patterns and the quality of communication, thus helping the practice move forward and get unstuck. Dr. Cope repeatedly commented, “I didn’t know that,” as staff shared their concerns and challenges. For example, Dr. Cope was amazed when the front desk described the amount of time and degree of disruption caused by drug reps constantly coming into the office. Together, the team was able to come up with a solution—setting aside a special time for drug reps, rather than allowing them to arrive whenever they chose—that worked for physicians and staff alike.

Our current project notes from Everyday Primary Care reflect a very different and vibrant practice, in which the atmosphere is charged with hope and everyone reports being more relaxed—though just as busy. Office processes have improved and space is less cluttered. Chart audit scores reveal improved quality of chronic care and preventive services. Because practice members have learned to communicate across the barriers of job classification and hierarchy, they are able to solve problems as they arise without allowing things to fester. These improved relationships led to an enhanced understanding of complex issues like patient triage and scheduling and more numerous and accurate memories of how the practice has operated over the years.21-23

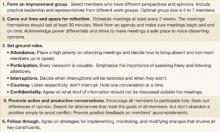

Our research has taught us that practices that pay attention to building strong relationships are better able to deal with the surprise and uncertainty that characterize modern health care delivery.24-26 The primary care management literature has highlighted a number of practical strategies for enhancing relationships and communication, including the use of RAP teams, huddles, effective team meetings, and high-performing clinical teams.15,27-29 In addition, we refer the reader to The Team Handbook, 3rd ed., by Peter R. Scholtes, Brian L. Joiner, and Barbara J. Streibel. The handbook contains a wide range of practical teambuilding strategies in an easily accessible style.30 FIGURE 1 summarizes 5 tips for building critical relationships in your own practice.

FIGURE 1

5 tips for building critical relationships

Interact with the “local fitness landscape”

Our second insight is that practices must learn to interact with what we call the “local fitness landscape.”31-33 To understand what that term implies, imagine your hometown with multiple primary care offices of different sizes, a variety of specialty practices, 2 or 3 competing hospital systems, multiple insurance options, businesses, housing clusters representing different social classes, schools, banks, scattered farms, industries, waterways, animals and plants, transportation systems, and political and religious institutions. The totality of all these elements is the local fitness landscape.

The landscape is a dynamic, fluid system within which the component parts respond to and influence each other. Everyday Primary Care is embedded in such a landscape, acting on and being acted upon by other parts of the system. Unfortunately, like most practices we observed, Everyday tended to ignore or resist the local fitness landscape rather than trying to understand and adapt to it. The physicians felt trapped by environmental constraints and frustrated by the turbulence they observed.

What constraints does Everyday Primary Care face? When we first visited this practice, we could see that the facility was too small for the growing volume of patients. The physician-owners knew the space wasn’t conducive to optimum patient care, but told us they could not afford to pay higher rent for larger quarters. Similarly, they understood the potential of electronic medical records (EMRs), but hadn’t been able to find time or money to support the transition. Rising overhead expenses were outpacing practice productivity, as measured in the number of patients seen per day. What was worse, the need to see so many patients was making it more difficult to address the needs of their aging and medically complex patient population.

Looking outward can help

Despite these constraints, internal conversations generated through RAP sessions led practice staff to reach out to other physicians and physician organizations for information. They compared notes with other practices on questions like how their computerized billing system functions, or how to word a letter to patients announcing a new policy on prescription refills. These external conversations expanded the practice’s notions of what was possible and gave them opportunities to share information and learn of new approaches other practices were developing. The result was a newfound level of energy and hope within the practice and exposure to new ideas from the outside.

Learning from the landscape. Numerous conversations with physician organizations, neighboring practices, and a local hospital system yielded new solutions for recalcitrant problems: How to make better use of existing office space, for example, and where to find support for long-range strategic planning. These contacts exposed Everyday to the experiences of other practices with EMRs, and the practice’s physicians have now selected and implemented their own system. The practice was finally able to address the inevitable retirement of 1 of the physicians and now has a succession plan in place. In sum, Everyday learned how to interact and adjust to the changing environment and no longer worried about survival.

Practices co-evolve with all the other systems in a constantly changing fitness landscape. As practice members navigate the local fitness landscapes, they make decisions among competing demands and priorities to maintain their own financial viability and internal stability. What seems to characterize innovative primary care practices is that they don’t wait to react to the next environmental change. Rather, by paying attention to local relationships, they improve the chances that co-evolution will move the practice in desired ways.

Making much-needed connections

There are a number of ways that practices can engage their fitness landscapes, but perhaps the most powerful is creating the time and space to meet with colleagues—either locally or regionally. The most effective approaches are likely to be those that allow sharing experiences and ideas over time, rather than one-time, opportunistic conversations that occur, say, at national and state academy meetings. Practices can participate in activities of regional Practice-Based Research Networks, local residency programs, or even form their own local support group.34,35 To learn how you can connect with a regional Practice-Based Research Network, go to the AHRQ website (http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt). FIGURE 2 summarizes 4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape.

FIGURE 2

4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape

One size doesn’t fit all: Strategic alternatives

When practices build critical relationships and pay attention to their local fitness landscape, they co-evolve improvements that make sense in the context of their unique characteristics and circumstances. Our research shows that practices use a range of alternative strategies to meet the needs of patients, their communities, and themselves. For example, while we have observed primary care offices using EMRs that have achieved high levels of adherence to diabetes guidelines, we have also found high adherence rates in practices that use paper charts.19 We have seen different, successful approaches to the delivery of preventive health services.11 Some practices involve staff in assuring protocol adherence and others don’t. Some use reminder systems and others don’t. Several practices with higher rates of preventive service delivery use none of these. A recent evaluation of 15 case studies of family practices using teams to implement the chronic care model showed the value of different types of teams in different practices.36

Variability and standardization. The emergence of processes and outcome measures designed to meet the needs of a particular local setting (fitness landscape) appeals to our sense of equity and common sense. Yet variations like these fly in the face of prevailing models and guidelines that emphasize standardized processes. Many health plans and provider organizations insist on evidence-based “best practices” and “optimized models” for delivering primary care.37-39 They assume that if we know the goals, there is a best way to get everyone to achieve them.

A better strategy is to determine when variability and tailoring are more appropriate and then use standardization to help create more time for those processes that require variation. Thus, the practice can use a standardized protocol to turn over immunizations to staff in order to free clinicians to spend more time interacting directly with patients.

Multiple pathways to excellence. Medical practice is full of surprises and complexities. We used to believe that the right tools in the hands of accountable individuals using good management systems would produce best practice outcomes. But we have learned that no single right tool or individual management strategy works consistently in primary care.

We now believe that the relationship system within the practice is a critical element in creating an optimal healing environment. Practices with improved relationship systems exhibit more resilience in weathering a hostile environment, while discovering their own unique model of successful primary care. Such practices can thrive, provide improved quality of patient-centered care, and find professional satisfaction and joy in daily work. We hope that the health care reform plans now being debated in Congress will be informed by these insights and provide space for multiple models of care delivery to emerge.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin F. Crabtree, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Medical school, 1 World’s Fair Drive, First Floor, Somerset, NJ 08873; crabtrbf@umdnj.edu

1. Showstack JA, Rothman AA, Hassmiller S. The Future of Primary Care. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

3. Institute of Medicine. Division of Health Care services. Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Donaldson MS. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

4. Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32.

5. Society of General Internal Medicine. Future of general internal medicine. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?section=site&pageId=366. Accessed July 7, 2009.

6. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A primary care home for Americans: putting the house in order. JAMA. 2002;288:889-893.

7. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care: Strategies and Tools for a Better Practice. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2007.

8. Moore G, Showstack J. Primary care medicine in crisis: toward reconstruction and renewal. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:244-247.

9. Direct Observation of Primary Care (DOPC) Writing Group. Conducting the direct observation of primary care study. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:345-352.

10. Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:377-389.

11. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

12. Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:20-28.

13. Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, et al. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:296-300.

14. Cohen D, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49:155-168;discussion 169–170.

15. Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:438-446.

16. Stange KC, Jaen CR, Flocke SA, et al. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:363-368.

17. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Aita VA, et al. Primary care practice organization and preventive services delivery: a qualitative analysis. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:403-409.

18. Ohman-Strickland PA, Orzano AJ, Hudson SV, et al. Quality of diabetes care in family medicine practices: influence of nurse-practitioners and physician’s assistants. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:14-22.

19. Crosson JC, Ohman-Strickland PA, Hahn KA, et al. Electronic medical records and diabetes quality of care: results from a sample of family medicine practices. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:209-215.

20. Tallia AF, Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR, Jr., et al. 7 characteristics of successful work relationships. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:47-50.

21. Weick KE. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

22. Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001.

23. Weick KE. Making Sense of the Organization. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers; 2001.

24. McDaniel RR, Jr, Jordan ME, Fleeman BF. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28:266-278.

25. Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, et al. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:369-376.

26. Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:872-878.

27. Stewart EE, Johnson BC. Improve office efficiency in mere minutes. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:27-29.

28. Shenkel R. How to make your meetings more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10:59-60.

29. Moore LG. Creating a high-performing clinical team. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:38-40.

30. Scholtes P, Joiner B, Streibel B. The Team Handbook. 3rd ed. Madison, Wisc: Oriel Incorporated; 2003.

31. Capra F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. 1st Anchor Books ed. New York: Anchor Books; 1996.

32. Holland JH. Emergence: from Chaos to Order. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1998.

33. Olson EE, Eoyang GH. Facilitating Organization Change: Lessons from Complexity Science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 2001.

34. Lanier D. Primary care practice-based research comes of age in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S2-S4.

35. Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S12-S20.

36. Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: Lessons from 15 case studies. Oakland, Calif: California HealthCare Foundation; July 2007. Available at: www.chcf.org/topics/chronicdisease/index.cfm?itemID=133375. Accessed March 18, 2008.

37. Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff. 2002;21:80-90.

38. Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998;280:1000-1005.

39. McGlynn EA. An evidence-based national quality measurement and reporting system. Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1):S8-S15.

- Building strong relationships among physicians and staff improves the practice’s ability to deal with the uncertainties of a rapidly changing environment (B).

- Interacting proactively with the economic, social, political, and cultural environment—the practice landscape—provides opportunities for adaptation and ongoing learning (C).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

“Everyday Primary Care,” a popular, urban 3-physician family medicine office, has served mostly middle- and working-class people for more than 25 years. Most of the patients have grown older with Drs. Newman and Cope and now have a substantial chronic disease burden. Dr. Varimore, Dr. Cope’s son, has recently joined the practice. He replaced a long-time partner who left in frustration to do emergency medicine.

On a typical day, Dr. Cope enters the crowded waiting room, sighs, and walks quickly toward the nurses’ station where her third scheduled patient has just arrived; her first 2 patients are already waiting in examining rooms. In her tiny office, stacks of charts, phone messages, and forms await her attention. Phones ring constantly. Rushing to see her first patient, Dr. Cope squeezes past her nursing assistant in the narrow hallway. She catches a glimpse of her partner, Dr. Newman, at the end of the corridor. They grunt a word of greeting, but say nothing more. In fact, the physicians and their staff have barely spoken to each other in days.

The 2 older physicians were hopeful that Dr. Varimore would infuse fresh energy into the practice, but the only thing that has changed with his arrival is an increase in the number of patients they see and the expenses of running the office. When the door finally closes at the end of a long day, everyone leaves feeling exhausted and alone.

A toxic atmosphere

The situation at Everyday Primary Care is not unusual.1 These are unhealthy times for most primary care practices. Despite the critical role that primary care is expected to play in health care reform, there is tremendous uncertainty about the future viability of primary care practice.1-6 An alarming number of primary care physicians are leaving practice or taking early retirement as frustration and exhaustion move deeply into our community.1,7,8 Staff turnover is high and disruptive. Primary care physicians feel buffeted by conflicting patient demands, insurance coverage restrictions, inadequate Medicare reimbursement, multiple and often inconsistent practice guidelines, and onerous government regulations. Primary care practices suffer from a culture of despair that impedes decision-making. These practices—and the physicians who struggle to keep them viable—need to develop resilience to survive in this hostile climate and improve the quality of care they provide.

Research-based strategies. This article suggests strategies for primary care practices to move forward—whatever proposed reforms emerge from the current debate. The strategies we propose derive from specific, concrete observations gathered during a 15-year program of research that included nearly 500 primary care offices.9-16 (In fact, Everyday Primary Care is an actual practice that participated in 1 of our studies, though we’ve changed its name and the names of the physicians.) Our research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and included both descriptive and intervention projects. Our studies provided in-depth descriptions of a wide variety of primary care practices, as well as new models for describing change.10,14,15 The practices varied in how they delivered preventive services, in their cancer-related prevention and screening activities, and in the way they managed chronic disease.11,14,17-19 Yet across all these variations, we found a pattern in which educated, well-trained professionals and staff wanted to provide good care, but found themselves thwarted in their efforts to succeed.

What’s going on here? We sought to understand what was really happening in these primary care practices and to formulate strategies to help them become better for patients, staff, and clinicians.

We came up with 2 fundamental insights:

- Practices that focus on building strong internal relationships are better able to deal with surprise and uncertainty.

- Practices that are proactive in interacting with the changing environment will find multiple ways to achieve effective health care delivery.

Work on building those relationships

In our research, we repeatedly observed that careful attention to the relationships among all the people (clinical and nonclinical staff) working within each practice is critical to improving practice processes and outcomes.20 We wanted to learn why relationships mattered so much and how they could be improved. What we found can best be explained by taking another look at Everyday Primary Care.

The physician-owners of everyday Primary Care, feeling stressed out and recognizing that “things are not good here,” signed up to participate in 1 of our studies. Participation required allowing an outside facilitator to observe practice operations and conduct open-ended interviews with physicians and staff over a 2-week period, followed by a series of 12 weekly meetings. In addition, physicians and staff agreed to fill out multiple surveys during the study process and allow researchers to audit the charts of randomly selected patient samples.

One year after Everyday Primary Care signed up, the office space was still cramped, the financial situation was no better, and environmental pressures were continuing to mount. And yet, the practice felt like a different place, one filled with energy and hope. What had happened?

RAP, huddles, effective teams. Most importantly, the quality and types of relationships within the practice had changed. At our suggestion, the practice formed a RAP (reflective adaptive process) team under the guidance of a facilitator—a nurse we trained in basic facilitation skills, including effective meeting strategies, brainstorming, and conflict resolution. The team consisted of physician leaders (both Drs. Cope and Varimore attended all meetings), the practice manager, representatives from each part of the practice (billing, front desk, nursing staff, insurance clerk), and a patient.15 The RAP intervention was designed to provide members with time and space to reflect and opportunities to learn the value of communication, respectful interaction, and listening to diverse opinions and perspectives.20 The team met with the facilitator for 1 hour every week, reviewed the practice’s vision, and developed and implemented strategies for solving prioritized practice issues and problems.

Brainstorming helped identify recurrent problems. As the RAP meetings progressed, it became clear that despite the close quarters, each part of the practice was isolated from the others and all team members were frustrated by their inability to influence the lead physician, Dr. Cope. Over time, the RAP meetings changed the relationship patterns and the quality of communication, thus helping the practice move forward and get unstuck. Dr. Cope repeatedly commented, “I didn’t know that,” as staff shared their concerns and challenges. For example, Dr. Cope was amazed when the front desk described the amount of time and degree of disruption caused by drug reps constantly coming into the office. Together, the team was able to come up with a solution—setting aside a special time for drug reps, rather than allowing them to arrive whenever they chose—that worked for physicians and staff alike.

Our current project notes from Everyday Primary Care reflect a very different and vibrant practice, in which the atmosphere is charged with hope and everyone reports being more relaxed—though just as busy. Office processes have improved and space is less cluttered. Chart audit scores reveal improved quality of chronic care and preventive services. Because practice members have learned to communicate across the barriers of job classification and hierarchy, they are able to solve problems as they arise without allowing things to fester. These improved relationships led to an enhanced understanding of complex issues like patient triage and scheduling and more numerous and accurate memories of how the practice has operated over the years.21-23

Our research has taught us that practices that pay attention to building strong relationships are better able to deal with the surprise and uncertainty that characterize modern health care delivery.24-26 The primary care management literature has highlighted a number of practical strategies for enhancing relationships and communication, including the use of RAP teams, huddles, effective team meetings, and high-performing clinical teams.15,27-29 In addition, we refer the reader to The Team Handbook, 3rd ed., by Peter R. Scholtes, Brian L. Joiner, and Barbara J. Streibel. The handbook contains a wide range of practical teambuilding strategies in an easily accessible style.30 FIGURE 1 summarizes 5 tips for building critical relationships in your own practice.

FIGURE 1

5 tips for building critical relationships

Interact with the “local fitness landscape”

Our second insight is that practices must learn to interact with what we call the “local fitness landscape.”31-33 To understand what that term implies, imagine your hometown with multiple primary care offices of different sizes, a variety of specialty practices, 2 or 3 competing hospital systems, multiple insurance options, businesses, housing clusters representing different social classes, schools, banks, scattered farms, industries, waterways, animals and plants, transportation systems, and political and religious institutions. The totality of all these elements is the local fitness landscape.

The landscape is a dynamic, fluid system within which the component parts respond to and influence each other. Everyday Primary Care is embedded in such a landscape, acting on and being acted upon by other parts of the system. Unfortunately, like most practices we observed, Everyday tended to ignore or resist the local fitness landscape rather than trying to understand and adapt to it. The physicians felt trapped by environmental constraints and frustrated by the turbulence they observed.

What constraints does Everyday Primary Care face? When we first visited this practice, we could see that the facility was too small for the growing volume of patients. The physician-owners knew the space wasn’t conducive to optimum patient care, but told us they could not afford to pay higher rent for larger quarters. Similarly, they understood the potential of electronic medical records (EMRs), but hadn’t been able to find time or money to support the transition. Rising overhead expenses were outpacing practice productivity, as measured in the number of patients seen per day. What was worse, the need to see so many patients was making it more difficult to address the needs of their aging and medically complex patient population.

Looking outward can help

Despite these constraints, internal conversations generated through RAP sessions led practice staff to reach out to other physicians and physician organizations for information. They compared notes with other practices on questions like how their computerized billing system functions, or how to word a letter to patients announcing a new policy on prescription refills. These external conversations expanded the practice’s notions of what was possible and gave them opportunities to share information and learn of new approaches other practices were developing. The result was a newfound level of energy and hope within the practice and exposure to new ideas from the outside.

Learning from the landscape. Numerous conversations with physician organizations, neighboring practices, and a local hospital system yielded new solutions for recalcitrant problems: How to make better use of existing office space, for example, and where to find support for long-range strategic planning. These contacts exposed Everyday to the experiences of other practices with EMRs, and the practice’s physicians have now selected and implemented their own system. The practice was finally able to address the inevitable retirement of 1 of the physicians and now has a succession plan in place. In sum, Everyday learned how to interact and adjust to the changing environment and no longer worried about survival.

Practices co-evolve with all the other systems in a constantly changing fitness landscape. As practice members navigate the local fitness landscapes, they make decisions among competing demands and priorities to maintain their own financial viability and internal stability. What seems to characterize innovative primary care practices is that they don’t wait to react to the next environmental change. Rather, by paying attention to local relationships, they improve the chances that co-evolution will move the practice in desired ways.

Making much-needed connections

There are a number of ways that practices can engage their fitness landscapes, but perhaps the most powerful is creating the time and space to meet with colleagues—either locally or regionally. The most effective approaches are likely to be those that allow sharing experiences and ideas over time, rather than one-time, opportunistic conversations that occur, say, at national and state academy meetings. Practices can participate in activities of regional Practice-Based Research Networks, local residency programs, or even form their own local support group.34,35 To learn how you can connect with a regional Practice-Based Research Network, go to the AHRQ website (http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt). FIGURE 2 summarizes 4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape.

FIGURE 2

4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape

One size doesn’t fit all: Strategic alternatives

When practices build critical relationships and pay attention to their local fitness landscape, they co-evolve improvements that make sense in the context of their unique characteristics and circumstances. Our research shows that practices use a range of alternative strategies to meet the needs of patients, their communities, and themselves. For example, while we have observed primary care offices using EMRs that have achieved high levels of adherence to diabetes guidelines, we have also found high adherence rates in practices that use paper charts.19 We have seen different, successful approaches to the delivery of preventive health services.11 Some practices involve staff in assuring protocol adherence and others don’t. Some use reminder systems and others don’t. Several practices with higher rates of preventive service delivery use none of these. A recent evaluation of 15 case studies of family practices using teams to implement the chronic care model showed the value of different types of teams in different practices.36

Variability and standardization. The emergence of processes and outcome measures designed to meet the needs of a particular local setting (fitness landscape) appeals to our sense of equity and common sense. Yet variations like these fly in the face of prevailing models and guidelines that emphasize standardized processes. Many health plans and provider organizations insist on evidence-based “best practices” and “optimized models” for delivering primary care.37-39 They assume that if we know the goals, there is a best way to get everyone to achieve them.

A better strategy is to determine when variability and tailoring are more appropriate and then use standardization to help create more time for those processes that require variation. Thus, the practice can use a standardized protocol to turn over immunizations to staff in order to free clinicians to spend more time interacting directly with patients.

Multiple pathways to excellence. Medical practice is full of surprises and complexities. We used to believe that the right tools in the hands of accountable individuals using good management systems would produce best practice outcomes. But we have learned that no single right tool or individual management strategy works consistently in primary care.

We now believe that the relationship system within the practice is a critical element in creating an optimal healing environment. Practices with improved relationship systems exhibit more resilience in weathering a hostile environment, while discovering their own unique model of successful primary care. Such practices can thrive, provide improved quality of patient-centered care, and find professional satisfaction and joy in daily work. We hope that the health care reform plans now being debated in Congress will be informed by these insights and provide space for multiple models of care delivery to emerge.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin F. Crabtree, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Medical school, 1 World’s Fair Drive, First Floor, Somerset, NJ 08873; crabtrbf@umdnj.edu

- Building strong relationships among physicians and staff improves the practice’s ability to deal with the uncertainties of a rapidly changing environment (B).

- Interacting proactively with the economic, social, political, and cultural environment—the practice landscape—provides opportunities for adaptation and ongoing learning (C).

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

“Everyday Primary Care,” a popular, urban 3-physician family medicine office, has served mostly middle- and working-class people for more than 25 years. Most of the patients have grown older with Drs. Newman and Cope and now have a substantial chronic disease burden. Dr. Varimore, Dr. Cope’s son, has recently joined the practice. He replaced a long-time partner who left in frustration to do emergency medicine.

On a typical day, Dr. Cope enters the crowded waiting room, sighs, and walks quickly toward the nurses’ station where her third scheduled patient has just arrived; her first 2 patients are already waiting in examining rooms. In her tiny office, stacks of charts, phone messages, and forms await her attention. Phones ring constantly. Rushing to see her first patient, Dr. Cope squeezes past her nursing assistant in the narrow hallway. She catches a glimpse of her partner, Dr. Newman, at the end of the corridor. They grunt a word of greeting, but say nothing more. In fact, the physicians and their staff have barely spoken to each other in days.

The 2 older physicians were hopeful that Dr. Varimore would infuse fresh energy into the practice, but the only thing that has changed with his arrival is an increase in the number of patients they see and the expenses of running the office. When the door finally closes at the end of a long day, everyone leaves feeling exhausted and alone.

A toxic atmosphere

The situation at Everyday Primary Care is not unusual.1 These are unhealthy times for most primary care practices. Despite the critical role that primary care is expected to play in health care reform, there is tremendous uncertainty about the future viability of primary care practice.1-6 An alarming number of primary care physicians are leaving practice or taking early retirement as frustration and exhaustion move deeply into our community.1,7,8 Staff turnover is high and disruptive. Primary care physicians feel buffeted by conflicting patient demands, insurance coverage restrictions, inadequate Medicare reimbursement, multiple and often inconsistent practice guidelines, and onerous government regulations. Primary care practices suffer from a culture of despair that impedes decision-making. These practices—and the physicians who struggle to keep them viable—need to develop resilience to survive in this hostile climate and improve the quality of care they provide.

Research-based strategies. This article suggests strategies for primary care practices to move forward—whatever proposed reforms emerge from the current debate. The strategies we propose derive from specific, concrete observations gathered during a 15-year program of research that included nearly 500 primary care offices.9-16 (In fact, Everyday Primary Care is an actual practice that participated in 1 of our studies, though we’ve changed its name and the names of the physicians.) Our research was funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and included both descriptive and intervention projects. Our studies provided in-depth descriptions of a wide variety of primary care practices, as well as new models for describing change.10,14,15 The practices varied in how they delivered preventive services, in their cancer-related prevention and screening activities, and in the way they managed chronic disease.11,14,17-19 Yet across all these variations, we found a pattern in which educated, well-trained professionals and staff wanted to provide good care, but found themselves thwarted in their efforts to succeed.

What’s going on here? We sought to understand what was really happening in these primary care practices and to formulate strategies to help them become better for patients, staff, and clinicians.

We came up with 2 fundamental insights:

- Practices that focus on building strong internal relationships are better able to deal with surprise and uncertainty.

- Practices that are proactive in interacting with the changing environment will find multiple ways to achieve effective health care delivery.

Work on building those relationships

In our research, we repeatedly observed that careful attention to the relationships among all the people (clinical and nonclinical staff) working within each practice is critical to improving practice processes and outcomes.20 We wanted to learn why relationships mattered so much and how they could be improved. What we found can best be explained by taking another look at Everyday Primary Care.

The physician-owners of everyday Primary Care, feeling stressed out and recognizing that “things are not good here,” signed up to participate in 1 of our studies. Participation required allowing an outside facilitator to observe practice operations and conduct open-ended interviews with physicians and staff over a 2-week period, followed by a series of 12 weekly meetings. In addition, physicians and staff agreed to fill out multiple surveys during the study process and allow researchers to audit the charts of randomly selected patient samples.

One year after Everyday Primary Care signed up, the office space was still cramped, the financial situation was no better, and environmental pressures were continuing to mount. And yet, the practice felt like a different place, one filled with energy and hope. What had happened?

RAP, huddles, effective teams. Most importantly, the quality and types of relationships within the practice had changed. At our suggestion, the practice formed a RAP (reflective adaptive process) team under the guidance of a facilitator—a nurse we trained in basic facilitation skills, including effective meeting strategies, brainstorming, and conflict resolution. The team consisted of physician leaders (both Drs. Cope and Varimore attended all meetings), the practice manager, representatives from each part of the practice (billing, front desk, nursing staff, insurance clerk), and a patient.15 The RAP intervention was designed to provide members with time and space to reflect and opportunities to learn the value of communication, respectful interaction, and listening to diverse opinions and perspectives.20 The team met with the facilitator for 1 hour every week, reviewed the practice’s vision, and developed and implemented strategies for solving prioritized practice issues and problems.

Brainstorming helped identify recurrent problems. As the RAP meetings progressed, it became clear that despite the close quarters, each part of the practice was isolated from the others and all team members were frustrated by their inability to influence the lead physician, Dr. Cope. Over time, the RAP meetings changed the relationship patterns and the quality of communication, thus helping the practice move forward and get unstuck. Dr. Cope repeatedly commented, “I didn’t know that,” as staff shared their concerns and challenges. For example, Dr. Cope was amazed when the front desk described the amount of time and degree of disruption caused by drug reps constantly coming into the office. Together, the team was able to come up with a solution—setting aside a special time for drug reps, rather than allowing them to arrive whenever they chose—that worked for physicians and staff alike.

Our current project notes from Everyday Primary Care reflect a very different and vibrant practice, in which the atmosphere is charged with hope and everyone reports being more relaxed—though just as busy. Office processes have improved and space is less cluttered. Chart audit scores reveal improved quality of chronic care and preventive services. Because practice members have learned to communicate across the barriers of job classification and hierarchy, they are able to solve problems as they arise without allowing things to fester. These improved relationships led to an enhanced understanding of complex issues like patient triage and scheduling and more numerous and accurate memories of how the practice has operated over the years.21-23

Our research has taught us that practices that pay attention to building strong relationships are better able to deal with the surprise and uncertainty that characterize modern health care delivery.24-26 The primary care management literature has highlighted a number of practical strategies for enhancing relationships and communication, including the use of RAP teams, huddles, effective team meetings, and high-performing clinical teams.15,27-29 In addition, we refer the reader to The Team Handbook, 3rd ed., by Peter R. Scholtes, Brian L. Joiner, and Barbara J. Streibel. The handbook contains a wide range of practical teambuilding strategies in an easily accessible style.30 FIGURE 1 summarizes 5 tips for building critical relationships in your own practice.

FIGURE 1

5 tips for building critical relationships

Interact with the “local fitness landscape”

Our second insight is that practices must learn to interact with what we call the “local fitness landscape.”31-33 To understand what that term implies, imagine your hometown with multiple primary care offices of different sizes, a variety of specialty practices, 2 or 3 competing hospital systems, multiple insurance options, businesses, housing clusters representing different social classes, schools, banks, scattered farms, industries, waterways, animals and plants, transportation systems, and political and religious institutions. The totality of all these elements is the local fitness landscape.

The landscape is a dynamic, fluid system within which the component parts respond to and influence each other. Everyday Primary Care is embedded in such a landscape, acting on and being acted upon by other parts of the system. Unfortunately, like most practices we observed, Everyday tended to ignore or resist the local fitness landscape rather than trying to understand and adapt to it. The physicians felt trapped by environmental constraints and frustrated by the turbulence they observed.

What constraints does Everyday Primary Care face? When we first visited this practice, we could see that the facility was too small for the growing volume of patients. The physician-owners knew the space wasn’t conducive to optimum patient care, but told us they could not afford to pay higher rent for larger quarters. Similarly, they understood the potential of electronic medical records (EMRs), but hadn’t been able to find time or money to support the transition. Rising overhead expenses were outpacing practice productivity, as measured in the number of patients seen per day. What was worse, the need to see so many patients was making it more difficult to address the needs of their aging and medically complex patient population.

Looking outward can help

Despite these constraints, internal conversations generated through RAP sessions led practice staff to reach out to other physicians and physician organizations for information. They compared notes with other practices on questions like how their computerized billing system functions, or how to word a letter to patients announcing a new policy on prescription refills. These external conversations expanded the practice’s notions of what was possible and gave them opportunities to share information and learn of new approaches other practices were developing. The result was a newfound level of energy and hope within the practice and exposure to new ideas from the outside.

Learning from the landscape. Numerous conversations with physician organizations, neighboring practices, and a local hospital system yielded new solutions for recalcitrant problems: How to make better use of existing office space, for example, and where to find support for long-range strategic planning. These contacts exposed Everyday to the experiences of other practices with EMRs, and the practice’s physicians have now selected and implemented their own system. The practice was finally able to address the inevitable retirement of 1 of the physicians and now has a succession plan in place. In sum, Everyday learned how to interact and adjust to the changing environment and no longer worried about survival.

Practices co-evolve with all the other systems in a constantly changing fitness landscape. As practice members navigate the local fitness landscapes, they make decisions among competing demands and priorities to maintain their own financial viability and internal stability. What seems to characterize innovative primary care practices is that they don’t wait to react to the next environmental change. Rather, by paying attention to local relationships, they improve the chances that co-evolution will move the practice in desired ways.

Making much-needed connections

There are a number of ways that practices can engage their fitness landscapes, but perhaps the most powerful is creating the time and space to meet with colleagues—either locally or regionally. The most effective approaches are likely to be those that allow sharing experiences and ideas over time, rather than one-time, opportunistic conversations that occur, say, at national and state academy meetings. Practices can participate in activities of regional Practice-Based Research Networks, local residency programs, or even form their own local support group.34,35 To learn how you can connect with a regional Practice-Based Research Network, go to the AHRQ website (http://pbrn.ahrq.gov/portal/server.pt). FIGURE 2 summarizes 4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape.

FIGURE 2

4 strategies for reaching out to your local landscape

One size doesn’t fit all: Strategic alternatives

When practices build critical relationships and pay attention to their local fitness landscape, they co-evolve improvements that make sense in the context of their unique characteristics and circumstances. Our research shows that practices use a range of alternative strategies to meet the needs of patients, their communities, and themselves. For example, while we have observed primary care offices using EMRs that have achieved high levels of adherence to diabetes guidelines, we have also found high adherence rates in practices that use paper charts.19 We have seen different, successful approaches to the delivery of preventive health services.11 Some practices involve staff in assuring protocol adherence and others don’t. Some use reminder systems and others don’t. Several practices with higher rates of preventive service delivery use none of these. A recent evaluation of 15 case studies of family practices using teams to implement the chronic care model showed the value of different types of teams in different practices.36

Variability and standardization. The emergence of processes and outcome measures designed to meet the needs of a particular local setting (fitness landscape) appeals to our sense of equity and common sense. Yet variations like these fly in the face of prevailing models and guidelines that emphasize standardized processes. Many health plans and provider organizations insist on evidence-based “best practices” and “optimized models” for delivering primary care.37-39 They assume that if we know the goals, there is a best way to get everyone to achieve them.

A better strategy is to determine when variability and tailoring are more appropriate and then use standardization to help create more time for those processes that require variation. Thus, the practice can use a standardized protocol to turn over immunizations to staff in order to free clinicians to spend more time interacting directly with patients.

Multiple pathways to excellence. Medical practice is full of surprises and complexities. We used to believe that the right tools in the hands of accountable individuals using good management systems would produce best practice outcomes. But we have learned that no single right tool or individual management strategy works consistently in primary care.

We now believe that the relationship system within the practice is a critical element in creating an optimal healing environment. Practices with improved relationship systems exhibit more resilience in weathering a hostile environment, while discovering their own unique model of successful primary care. Such practices can thrive, provide improved quality of patient-centered care, and find professional satisfaction and joy in daily work. We hope that the health care reform plans now being debated in Congress will be informed by these insights and provide space for multiple models of care delivery to emerge.

CORRESPONDENCE

Benjamin F. Crabtree, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Robert Wood Johnson Medical school, 1 World’s Fair Drive, First Floor, Somerset, NJ 08873; crabtrbf@umdnj.edu

1. Showstack JA, Rothman AA, Hassmiller S. The Future of Primary Care. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

3. Institute of Medicine. Division of Health Care services. Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Donaldson MS. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

4. Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32.

5. Society of General Internal Medicine. Future of general internal medicine. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?section=site&pageId=366. Accessed July 7, 2009.

6. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A primary care home for Americans: putting the house in order. JAMA. 2002;288:889-893.

7. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care: Strategies and Tools for a Better Practice. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2007.

8. Moore G, Showstack J. Primary care medicine in crisis: toward reconstruction and renewal. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:244-247.

9. Direct Observation of Primary Care (DOPC) Writing Group. Conducting the direct observation of primary care study. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:345-352.

10. Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:377-389.

11. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

12. Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:20-28.

13. Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, et al. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:296-300.

14. Cohen D, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49:155-168;discussion 169–170.

15. Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:438-446.

16. Stange KC, Jaen CR, Flocke SA, et al. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:363-368.

17. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Aita VA, et al. Primary care practice organization and preventive services delivery: a qualitative analysis. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:403-409.

18. Ohman-Strickland PA, Orzano AJ, Hudson SV, et al. Quality of diabetes care in family medicine practices: influence of nurse-practitioners and physician’s assistants. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:14-22.

19. Crosson JC, Ohman-Strickland PA, Hahn KA, et al. Electronic medical records and diabetes quality of care: results from a sample of family medicine practices. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:209-215.

20. Tallia AF, Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR, Jr., et al. 7 characteristics of successful work relationships. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:47-50.

21. Weick KE. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

22. Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001.

23. Weick KE. Making Sense of the Organization. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers; 2001.

24. McDaniel RR, Jr, Jordan ME, Fleeman BF. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28:266-278.

25. Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, et al. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:369-376.

26. Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:872-878.

27. Stewart EE, Johnson BC. Improve office efficiency in mere minutes. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:27-29.

28. Shenkel R. How to make your meetings more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10:59-60.

29. Moore LG. Creating a high-performing clinical team. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:38-40.

30. Scholtes P, Joiner B, Streibel B. The Team Handbook. 3rd ed. Madison, Wisc: Oriel Incorporated; 2003.

31. Capra F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. 1st Anchor Books ed. New York: Anchor Books; 1996.

32. Holland JH. Emergence: from Chaos to Order. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1998.

33. Olson EE, Eoyang GH. Facilitating Organization Change: Lessons from Complexity Science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 2001.

34. Lanier D. Primary care practice-based research comes of age in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S2-S4.

35. Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S12-S20.

36. Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: Lessons from 15 case studies. Oakland, Calif: California HealthCare Foundation; July 2007. Available at: www.chcf.org/topics/chronicdisease/index.cfm?itemID=133375. Accessed March 18, 2008.

37. Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff. 2002;21:80-90.

38. Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998;280:1000-1005.

39. McGlynn EA. An evidence-based national quality measurement and reporting system. Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1):S8-S15.

1. Showstack JA, Rothman AA, Hassmiller S. The Future of Primary Care. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2004.

2. Institute of Medicine. Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

3. Institute of Medicine. Division of Health Care services. Committee on the Future of Primary Care. Donaldson MS. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996.

4. Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al. The future of family medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32.

5. Society of General Internal Medicine. Future of general internal medicine. Available at: www.sgim.org/index.cfm?section=site&pageId=366. Accessed July 7, 2009.

6. Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A primary care home for Americans: putting the house in order. JAMA. 2002;288:889-893.

7. Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K. Improving Primary Care: Strategies and Tools for a Better Practice. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2007.

8. Moore G, Showstack J. Primary care medicine in crisis: toward reconstruction and renewal. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:244-247.

9. Direct Observation of Primary Care (DOPC) Writing Group. Conducting the direct observation of primary care study. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:345-352.

10. Stange KC, Zyzanski SJ, Jaen CR, et al. Illuminating the ‘black box’. A description of 4454 patient visits to 138 family physicians. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:377-389.

11. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Tallia AF, et al. Delivery of clinical preventive services in family medicine offices. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3:430-435.

12. Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, Zronek S, et al. A clinical trial of tailored office systems for preventive service delivery. The Study to Enhance Prevention by Understanding Practice (STEP-UP). Am J Prev Med. 2001;21:20-28.

13. Stange KC, Goodwin MA, Zyzanski SJ, et al. Sustainability of a practice-individualized preventive service delivery intervention. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25:296-300.

14. Cohen D, McDaniel RR, Jr, Crabtree BF, et al. A practice change model for quality improvement in primary care practice. J Healthc Manag. 2004;49:155-168;discussion 169–170.

15. Stroebel CK, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. How complexity science can inform a reflective process for improvement in primary care practices. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2005;31:438-446.

16. Stange KC, Jaen CR, Flocke SA, et al. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:363-368.

17. Crabtree BF, Miller WL, Aita VA, et al. Primary care practice organization and preventive services delivery: a qualitative analysis. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:403-409.

18. Ohman-Strickland PA, Orzano AJ, Hudson SV, et al. Quality of diabetes care in family medicine practices: influence of nurse-practitioners and physician’s assistants. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:14-22.

19. Crosson JC, Ohman-Strickland PA, Hahn KA, et al. Electronic medical records and diabetes quality of care: results from a sample of family medicine practices. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:209-215.

20. Tallia AF, Lanham HJ, McDaniel RR, Jr., et al. 7 characteristics of successful work relationships. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:47-50.

21. Weick KE. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1995.

22. Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM. Managing the Unexpected: Assuring High Performance in an Age of Complexity. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2001.

23. Weick KE. Making Sense of the Organization. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Publishers; 2001.

24. McDaniel RR, Jr, Jordan ME, Fleeman BF. Surprise, Surprise, Surprise! A complexity science view of the unexpected. Health Care Manage Rev. 2003;28:266-278.

25. Miller WL, Crabtree BF, McDaniel R, et al. Understanding change in primary care practice using complexity theory. J Fam Pract. 1998;46:369-376.

26. Miller WL, McDaniel RR, Jr., Crabtree BF, et al. Practice jazz: understanding variation in family practices using complexity science. J Fam Pract. 2001;50:872-878.

27. Stewart EE, Johnson BC. Improve office efficiency in mere minutes. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14:27-29.

28. Shenkel R. How to make your meetings more productive. Fam Pract Manag. 2003;10:59-60.

29. Moore LG. Creating a high-performing clinical team. Fam Pract Manag. 2006;13:38-40.

30. Scholtes P, Joiner B, Streibel B. The Team Handbook. 3rd ed. Madison, Wisc: Oriel Incorporated; 2003.

31. Capra F. The Web of Life: A New Scientific Understanding of Living Systems. 1st Anchor Books ed. New York: Anchor Books; 1996.

32. Holland JH. Emergence: from Chaos to Order. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1998.

33. Olson EE, Eoyang GH. Facilitating Organization Change: Lessons from Complexity Science. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass/Pfeiffer; 2001.

34. Lanier D. Primary care practice-based research comes of age in the United States. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S2-S4.

35. Mold JW, Peterson KA. Primary care practice-based research networks: working at the interface between research and quality improvement. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(suppl 1):S12-S20.

36. Bodenheimer T. Building teams in primary care: Lessons from 15 case studies. Oakland, Calif: California HealthCare Foundation; July 2007. Available at: www.chcf.org/topics/chronicdisease/index.cfm?itemID=133375. Accessed March 18, 2008.

37. Berwick DM. A user’s manual for the IOM’s ‘Quality Chasm’ report. Health Aff. 2002;21:80-90.

38. Chassin MR, Galvin RW. The urgent need to improve health care quality. Institute of Medicine National Roundtable on Health Care Quality. JAMA. 1998;280:1000-1005.

39. McGlynn EA. An evidence-based national quality measurement and reporting system. Med Care. 2003;41(suppl 1):S8-S15.