User login

Previous studies have advocated the importance of effective communication between clinicians as a critical component in the provision of high‐quality patient care.[1, 2, 3, 4] There is increasing interest in the use of information and communication technologies to improve how clinicians communicate in hospital settings. A number of hospitals have implemented different solutions to improve communication. These solutions include alphanumeric pagers,[5] smartphones,[6] e‐mail,[7] secure text messaging,[8] and a Web‐based interdisciplinary communication tool.[9]

These systems have different limitations that render them inefficient and likely inhibit collaborative care. Current systems, such as pagers, rely on the sender to ensure the message was received and are successful in delivering messages approximately 67% of the time.[5, 9, 10] Although alphanumeric pagers and secure text messaging can increase the likelihood of delivery, these messages are often isolated and not easily viewable by the whole care team.[11] Improved systems should also reduce unnecessary interruptions by providing support for both urgent and delayed messages. Finally, messages should be stored and retrievable to enable increased accountability and allow for review for quality improvement initiatives.

It is also important to consider the unintended consequences of technology implementations.[12] Moving communication to text messages and smartphones has the potential to reduce interprofessional relations and can increase confusion if used for complex issues.[10, 13] In this article, we present a system designed to improve interprofessional communication on general internal medicine wards by incorporating these desired features and describe the usage and attitudes toward the system, specifically assessing for effects on multiple domains including efficiency, interprofessional collaboration, and relationships.

METHODS

Research Question

Will nurses and physicians use a system designed to improve interprofessional communication and will they perceive it to be effective and improve workflow?

Setting

The study took place on the general internal medicine wards at Toronto General Hospital and Toronto Western Hospital, 2 large academic teaching hospitals. There are several general internal medicine wards at each site with approximately 80 beds at each site. At each site there are 4 clinical teaching units and 1 hospitalist team. The study was approved by the research ethics board at the University Health Network.

Intervention

To address issues with communication, we developed a systemClinical Message (CM)that included 2 main components: a physician handover tool and secure messaging module. The focus of CM was to improve communication and information flow among different healthcare providers (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and therapists) through a secure, shared platform.

Physician Handover

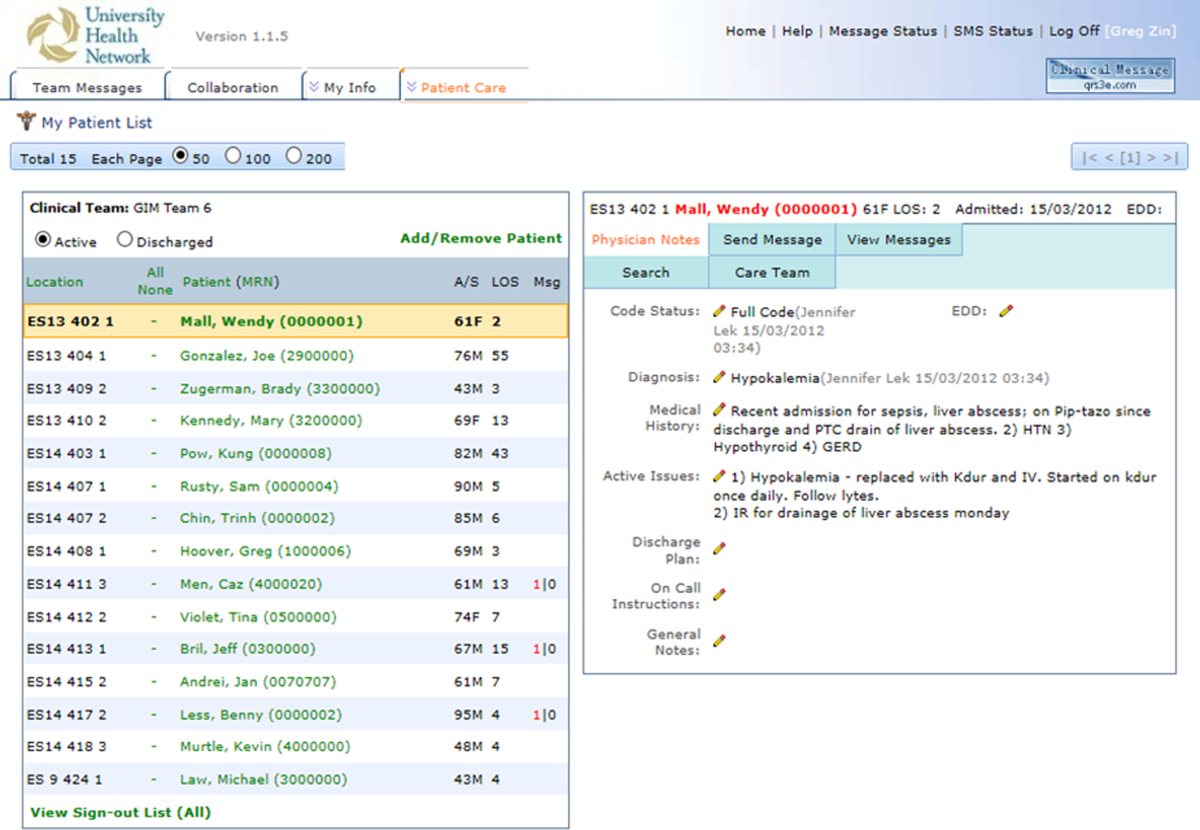

The physician handover tool was designed to facilitate the physician handover process at shift change and is used as a patient rounding tool for day‐to‐day management of patients. It is also accessed by nurses and other clinicians to view the physicians' notes and to stay informed on the overall care plan. The tool contains standard elements including a list of patients with the following information on each patient: demographics, diagnosis, code status, medical history, active issues, and discharge plans (Figure 1).

Secure Messaging

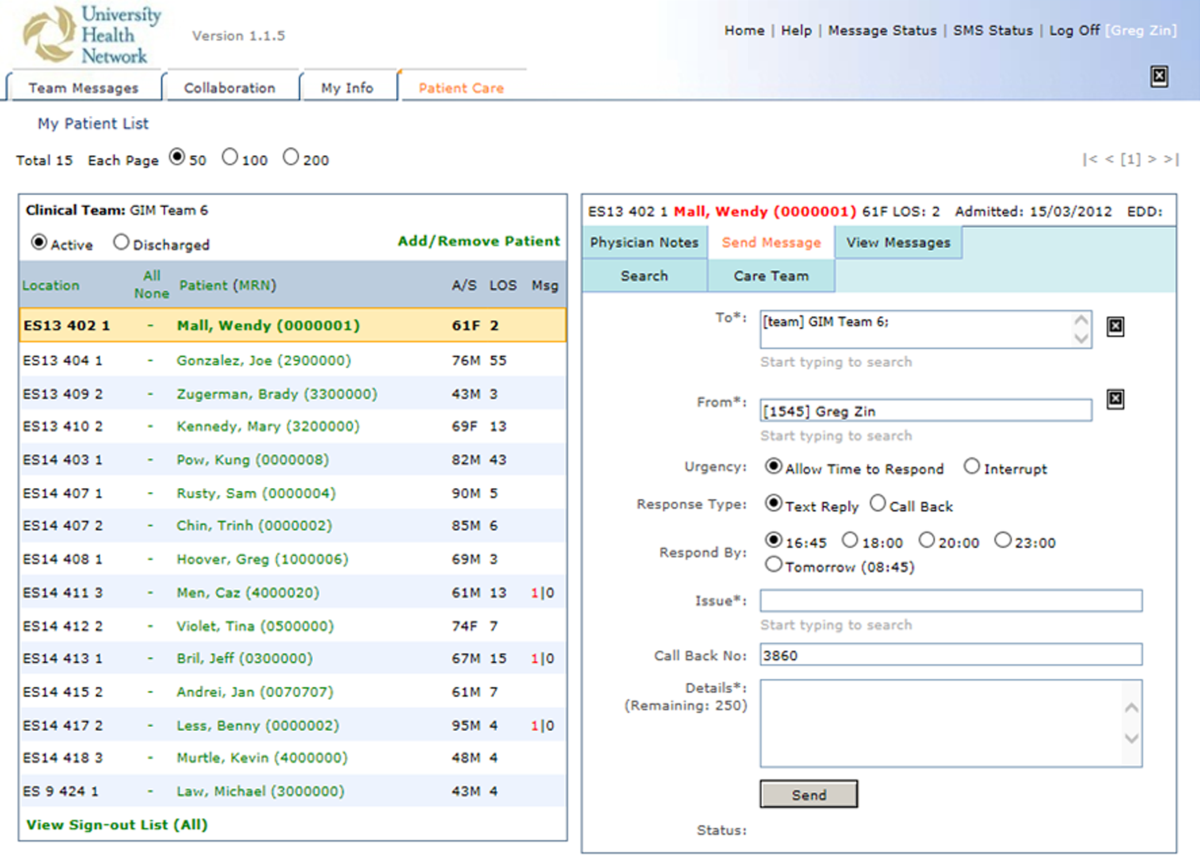

Secure messaging was designed around our dominant communication: nurses sending messages to physicians who would then respond. Nurses and other health professionals sent messages to the medical teams by accessing CM, selecting the appropriate patient, and filling out a message template. The system automatically populated the To field with the team assigned to the selected patient. Messaging for each team was centralized around a single team smartphone that was carried 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by a physician on that team. This removed the guesswork of trying to identify the individual physician responsible for that patient. For each message, a subject or issue and content were entered (Figure 2). Logic was also incorporated to reduce the amount of unnecessary interruptions. Senders would choose to send the message immediately as an interrupt message (urgent) for urgent/time sensitive issues or as an allow time to respond message (delayed). For the latter, the message was posted to the system where physicians could check and answer them. Interrupt messages were sent to the team smartphone using the Short Message Service (SMS) protocol. To try and ensure the communication loop on any issues was closed, when a message requested a response and did not receive it, the system sent another message. For urgent messages, a repeat message was initiated after 15 minutes. For delayed messages, the sender defined when they needed a response, typically within 2 to 8 hours. Senders were also able to select the mode of response that would best meet their needs from a workflow perspective: call back, text reply, or to specify that a reply was not required. Senders were also able to verify if the messages were received by the physician's smartphone. Physicians could view the messages within CM and reply. For messages that went to their team smartphone, physicians could respond from the smartphone through a secure Web link.

Because the messages were linked to the patients, they were visible to the entire care team, not just the message sender and recipient. If the care of the patient was transferred from 1 clinician to the next, the new clinician could easily review prior messages to understand recent patient events. The system was accessible through a browser on the intranet. The system regularly pulled patient demographic details such as name, age, medical record number, and location from our electronic medical record through a 1‐way interface. Information from this communication system was not considered part of the medical record but was retrievable.

The system was introduced as the new standard method of communication for nurses to reach physicians for all of the general internal medicine wards and for all medical teams at site 1 on May 2, 2011 and site 2 on June 6, 2011. The system replaced a text‐based Web‐paging system and supplemented the numeric pager carried by residents. Initial training of a half hour was provided to all nurses and residents.

Message Analysis for Usage Statistics

We analyzed messages created and sent via the CM system from May 2011 until August 2012. The extracted message information included date and time sent, issue, level of urgency, response type requested, roles of clinicians involved from the associated team, hospital site (senders and receivers), and message details. The following inclusion criteria were used for the analyses: (1) the senders and receivers of the messages could not be CM support staff, and (2) the messages sent were intended for the team smartphones used by the respective medical teams, not individual clinicians. Descriptive statistics and frequency analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and IBM SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Survey

Development of the Survey

We used standard methods to develop a survey to assess staff perceptions on the impact of the new communication system. Relevant questionnaire items were compiled from a systematic review of the literature for communication surveys and communication issues that included the following domains: efficiency, accountability, accuracy, collaboration, timeliness, richness of the communication medium, and impact on interprofessional relationships and verbal communication.[10, 14, 15] We carried out pilot testing with 5 nurses and physicians, and modified the questionnaires based on their feedback.

Sampling and Data Collection of the Survey

Survey participants consisted of 2 groups of clinicians: (1) medical trainees that included medical residents, medical interns, and clinical fellows, and (2) nursing staff that included part‐time and full‐time nurses. To qualify for inclusion, participants had to have used the CM system for at least a month prior to administration of the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Responses were recorded into an Excel spreadsheet that was imported into SPSS for analysis. Categorical variables were described using proportions. Survey comments were grouped into common themes, and themes mentioned by more than 1 respondent were reported.

RESULTS

Usage Analysis

A total of 60,969 messages were sent using CM between May 2, 2011 and August 19, 2012. On average, a team would receive 14.8 messages per day. Of all messages, 76.5% requested a text reply, 7.7% requested a call‐back, and 15.7% did not request a response. More than two‐thirds of messages at both hospitals were sent as immediate. Of the nonurgent messages, 86% were not replied to within the desired time, requiring a repeat message to be sent. Examples of different types of messages are shown in Table 1.

| Sender | Issue | Details | Priority | Desired Response Type | Time Created | Time Sent | Reply | Time Replied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Nurse | Vital sign | Pt's BP is 182/95, HR is 108 now. Previous at 0800 was 165/78; HR was 99. PT is not on antihypertensive meds. | Allow time to respond (23:00) | Text reply | 21:43 | 23:02 | OK. Will assess. | 23:03 |

| Nurse | NG tube | NG tube is in place. Can you please enter portable chest x‐ray to check placement ASAP? | Immediate | Text reply | 16:58 | 16:58 | Will do. | 17:00 |

| Nurse | Bloodwork | Pt creat=216. Pt has NS @ 75 cc/hr. Pt has noted crackles throughout lung fields and has productive cough; eating and drinking well. Would you like it continued as well? Pt O2Sat 93% RA; would you like 4 L of O2 continued? Pls call for telephone order. | Immediate | Call back | 12:53 | 13:04 | Dealt with it on phone. | 13:05 |

| Nurse | Pain control | Hello! Pt has been getting 1 mg hydromorphone IV q 1 hr and pain is still not controlled. Pt remains awake and alert. Thanks! | Immediate | Info only | 15:41 | 15:41 | Thank you. | 15:42 |

For messages requesting a text reply, 8.6% did not receive a reply. The median response time was 2.3 minutes (interquartile range of 5.8 minutes), but some messages did not receive a response even after a week, which skewed the distribution of response times. For those messages that did receive a reply, 68.9% of them were responded to within 5 minutes, and 84.5% were responded to within 15 minutes. Messages were predominantly received between 9 am and midnight (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). Because the sending of some messages was delayed, there appeared to be fewer messages received during protected educational times (89 am and 121 pm) as well as between midnight and 7 am compared to other times.

Survey Results

Between April 2013 and June 2013, 82 of 86 medical trainees (95.3%) and 83 of 116 nurses (71.6%) completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 81.7%. Clinicians perceived that CM appeared to have a positive impact on efficiency. In particular, 82.8% of physicians and 78.3% of nurses agreed or strongly agreed that CM helped speed up daily work tasks (Table 2). The majority of physicians and nurses agreed that the system increased accountability, increased timeliness of communication, and improved interprofessional relationships. It was not seen to be effective for communicating complex patient issues.

| No. of Subitems in Survey | Physician (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=82 | Nurse (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=83 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Positive impact on efficiency. | 7 | 58.9% | 66.6% |

| The CM system helps speed up my daily work tasks. | 82.8% | 78.3% | |

| Positive impact on physician‐nurse collaboration. | 6 | 55.3% | 58.5% |

| The CM system increases the amount of communication between nurses and physicians. | 50.6% | 67.1% | |

| Improved timeliness of communication. | 5 | 54.2% | 50.5% |

| Communication through the CM system helps me resolve patient issues within the appropriate time frames. | 66.7% | 55.6% | |

| Increased accountability. | 2 | 67.1% | 73.2% |

| Improved accuracy of communications. | 3 | 41.6% | 50.7% |

| Improved interprofessional relationships. | 2 | 62.2% | 53.6% |

| Increased verbal communications. | 2 | 35.1% | 25.3% |

| Richness of the communication medium. | 6 | 40.7% | 48.3% |

| I find the CM system useful for communicating complex patient issues. | 35.8% | 26.3% | |

| I would prefer CM over standard hospital communication methods such as numeric paging. | 1 | 68.3% | 76.5% |

| I enjoy using the CM system for clinical communication on the wards. | 1 | 63.0% | 79.0% |

| Communication through the CM system helps to reduce interruptions for physicians. | 1 | 45.7% | |

Survey comments revealed that nurses perceived a lack of desired response, whereas physicians noted being interrupted with low‐value information through the system (Table 3). Both commented that further functionality, such as an active message stream, would be of benefit. Difficulty in communicating complex issues was also noted.

| Issue | Occurrences | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | RN | Total | ||

| ||||

| Lack of response | 1 | 10 | 11 | It depends if they respond quickly or not. A few times I send the 2nd message to remind them of the issue. I also spend more time to check if they answer it or not. I even call their Blackberries at last to get a response. |

| Message stream | 3 | 4 | 7 | I wish that I could see follow‐up messages after my initial reply (ie, it would be nice to have an open message stream). |

| Difficult to communicate complex issues | 1 | 5 | 6 | Difficult to communicate complex issues. Takes a lot of time to respond, and it becomes inefficient when responding to nonurgent CM because it interrupts workflow. |

| Many messages are low‐value interrupts | 3 | 0 | 3 | CM is useful for handover between clinicians, but often it slows down the clinician when they are used for information‐related low‐value/noncritical messages between nurses and clinicians |

| Lack of detailed response | 0 | 3 | 3 | Specific messages regarding response to care is required most times. For example, acknowledged is not a favorable response. |

| Technical issues | 2 | 0 | 2 | I find CM very useful. We have had multiple issues with our Blackberry this month, and CM was not working. When it is up and running, however, it is a wonderful tool. |

| Discrepancy in perceived urgency | 2 | 0 | 2 | Discrepancy between what nurses find urgent and what we find urgent. |

DISCUSSION

We describe an implementation of a system to improve clinical communication in hospitals. The system was highly used and was perceived to improve communication by both nurses and physicians. Specifically, users found that the system increased efficiency, accountability, timeliness, and collaboration, but that there were issues with message clarity for complex medical issues.

Other systems and approaches have been implemented to improve communication. These included the use of alphanumeric pagers, e‐mail, secure texting, and smartphones. There is evidence that more advanced systems can improve efficiency for senders.[16] A recent randomized trial of secure text messaging found that it was perceived to be more efficient than paging, but overall usage was low and inconsistent.[8] There is also evidence that smartphones may increase interruptions, worsen interprofessional relationships, and cause issues with professional behavior.[10] Unfortunately, there are a limited number of interventions that improve communication, with some improving efficiency but none demonstrating improved patient‐oriented outcomes.[16, 17] This study evaluated a novel system, with functionality to link communication to patients, and created a system that aligned with the workflow of the clinicians. Messages were linked to the patient, not the sender or receiver, so other clinicians in the patient's circle of care could easily view the communication. Moreover, the system was designed to improve message response rates and allow for nonurgent messages.

Our communication system uses standard, commercially available components (smartphones, SMS), and relatively basic functionality (handover, secure messaging). Important findings are that the current system of paging can be transformed to a more efficient system that users will readily adopt. We found positive effects with components of the system. It appeared to improve efficiency and increase accountability. Accountability is crucial and moves from undocumented conversation to fully documented details of interactions. This can be used for both incident review and to review for quality improvement.

Using the system, physicians perceived that they were bothered by low‐value information, whereas nurses perceived a lack of response, and both found that the system was not ideal for complex messages. The mismatch between what physicians and nurses perceive as important has been attributed to their different timeframes and context.[18] For nurses with an upcoming change of shift, they wanted resolution of issues before handover. A physician on a different ward may not appreciate the context of a nurse having to directly interact with an irate family member. These different perceptions likely contributed to the lack of response to 8.6% of text messages. This is still better than other systems, such as paging, which can be as high as 33%.[10] For nonurgent items, clinicians would ideally check and clear items regularly from the system using a desktop computer, responding within the allotted timeframe. Unfortunately, this never became part of routine physician workflow, likely due to their busy workload, so many physicians would only respond when items became overdue. However, having a method to deal with nonurgent messages may have prevented some interruptions during protected educational times of trainees. The system was also not ideal for urgent or complex items. Complex items can be difficult to convey using the rarified communication medium of text messages.[19, 20] Urgent or complex issues are likely best resolved with a face‐to‐face or telephone conversation.

There are several limitations in our study that should be considered when interpreting the results. It is a study of usage and perceptions after implementation. Although more rigorous study is required to evaluate the effects, we see this as a first step in process improvement. Future research should measure the impact on improving patient care of this system and on patient outcomes such as adverse events. The study and intervention was limited to general internal medicine wards in 2 academic hospital settings where there are frequent rotations of medical personnel. The findings may not be generalizable to other hospital settings.

Future directions should be to further improve on the communication system and to educate and train staff on how to effectively communicate. Survey results showed that although users perceived increased efficiency, there was still significant opportunity to improve. One way to improve would be to have a mobile application in which physicians can easily review nonurgent items. Improvements could also be realized by educating clinicians on the use of the system and providing immediate feedback. Providing feedback to physicians on how well they respond could address nurses' issues around lack of timely response. By creating consensus between nurses and physicians on what is of high and low value to communicate could increase satisfaction for all users.

In summary, we present the usage and perceptions of a system designed to improve hospital communication. We found that there was high uptake, and that users perceived it to improve efficiency, collaboration, and accountability, but it may not be useful for communicating complex issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the nurses, physicians, residents, and other health professions on the general internal medicine ward for their patience and support as we continue to try to innovate. The authors also acknowledge the members of the information systems department (Shared Information Management Systems, University Health Network) who helped to support the Communication System, and the software developer, QRS, that helped to codevelop the software system.

Disclosures: The hospital was in a codevelopment agreement that has since terminated. No researcher or hospital received any funds from private industry for any purpose including personal or research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–376.

- , , , et al. Gaps in pediatric clinician communication and opportunities for improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(5):43–54.

- , , , , . Quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1996;164(12):754.

- , , , . Implementation and evaluation of an alphanumeric paging system on a resident inpatient teaching service. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E34–E40.

- , , , et al. Demonstrating the BlackBerry as a clinical communication tool: a pilot study conducted through the Centre for Innovation in Complex Care. Healthc Q. 2008;11(4):94–98.

- , , , . The use of wireless email to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):705–713.

- , , , , , . Smarter hospital communication: secure smartphone text messaging improves provider satisfaction and perception of efficacy, workflow. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):573–578.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , , , et al. The intended and unintended consequences of communication systems on general internal medicine inpatient care delivery: a prospective observational case study of five teaching hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(4):766–777.

- , , , et al. Improving hospital care and collaborative communications for the 21st century: key recommendations for general internal medicine. Interact J Med Res. 2012;1(2):e9.

- , , , , , . Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):82–90.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- , , , , . Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse‐physician questionnaire. Med Care. 1991;29(8):709–726.

- . Impact of communication medium on task performance and satisfaction: an examination of media‐richness theory. Inform Manag. 1999;35:295–312.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):589–597.

- , , , et al. Perceptions of urgency: defining the gap between what physicians and nurses perceive to be an urgent issue. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(5):378–386.

- , , , , , . Short message service or disService: issues with text messaging in a complex medical environment. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(4):278–284.

- , , . Instant messaging at the hospital: supporting articulation work? Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(9):753–761.

Previous studies have advocated the importance of effective communication between clinicians as a critical component in the provision of high‐quality patient care.[1, 2, 3, 4] There is increasing interest in the use of information and communication technologies to improve how clinicians communicate in hospital settings. A number of hospitals have implemented different solutions to improve communication. These solutions include alphanumeric pagers,[5] smartphones,[6] e‐mail,[7] secure text messaging,[8] and a Web‐based interdisciplinary communication tool.[9]

These systems have different limitations that render them inefficient and likely inhibit collaborative care. Current systems, such as pagers, rely on the sender to ensure the message was received and are successful in delivering messages approximately 67% of the time.[5, 9, 10] Although alphanumeric pagers and secure text messaging can increase the likelihood of delivery, these messages are often isolated and not easily viewable by the whole care team.[11] Improved systems should also reduce unnecessary interruptions by providing support for both urgent and delayed messages. Finally, messages should be stored and retrievable to enable increased accountability and allow for review for quality improvement initiatives.

It is also important to consider the unintended consequences of technology implementations.[12] Moving communication to text messages and smartphones has the potential to reduce interprofessional relations and can increase confusion if used for complex issues.[10, 13] In this article, we present a system designed to improve interprofessional communication on general internal medicine wards by incorporating these desired features and describe the usage and attitudes toward the system, specifically assessing for effects on multiple domains including efficiency, interprofessional collaboration, and relationships.

METHODS

Research Question

Will nurses and physicians use a system designed to improve interprofessional communication and will they perceive it to be effective and improve workflow?

Setting

The study took place on the general internal medicine wards at Toronto General Hospital and Toronto Western Hospital, 2 large academic teaching hospitals. There are several general internal medicine wards at each site with approximately 80 beds at each site. At each site there are 4 clinical teaching units and 1 hospitalist team. The study was approved by the research ethics board at the University Health Network.

Intervention

To address issues with communication, we developed a systemClinical Message (CM)that included 2 main components: a physician handover tool and secure messaging module. The focus of CM was to improve communication and information flow among different healthcare providers (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and therapists) through a secure, shared platform.

Physician Handover

The physician handover tool was designed to facilitate the physician handover process at shift change and is used as a patient rounding tool for day‐to‐day management of patients. It is also accessed by nurses and other clinicians to view the physicians' notes and to stay informed on the overall care plan. The tool contains standard elements including a list of patients with the following information on each patient: demographics, diagnosis, code status, medical history, active issues, and discharge plans (Figure 1).

Secure Messaging

Secure messaging was designed around our dominant communication: nurses sending messages to physicians who would then respond. Nurses and other health professionals sent messages to the medical teams by accessing CM, selecting the appropriate patient, and filling out a message template. The system automatically populated the To field with the team assigned to the selected patient. Messaging for each team was centralized around a single team smartphone that was carried 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by a physician on that team. This removed the guesswork of trying to identify the individual physician responsible for that patient. For each message, a subject or issue and content were entered (Figure 2). Logic was also incorporated to reduce the amount of unnecessary interruptions. Senders would choose to send the message immediately as an interrupt message (urgent) for urgent/time sensitive issues or as an allow time to respond message (delayed). For the latter, the message was posted to the system where physicians could check and answer them. Interrupt messages were sent to the team smartphone using the Short Message Service (SMS) protocol. To try and ensure the communication loop on any issues was closed, when a message requested a response and did not receive it, the system sent another message. For urgent messages, a repeat message was initiated after 15 minutes. For delayed messages, the sender defined when they needed a response, typically within 2 to 8 hours. Senders were also able to select the mode of response that would best meet their needs from a workflow perspective: call back, text reply, or to specify that a reply was not required. Senders were also able to verify if the messages were received by the physician's smartphone. Physicians could view the messages within CM and reply. For messages that went to their team smartphone, physicians could respond from the smartphone through a secure Web link.

Because the messages were linked to the patients, they were visible to the entire care team, not just the message sender and recipient. If the care of the patient was transferred from 1 clinician to the next, the new clinician could easily review prior messages to understand recent patient events. The system was accessible through a browser on the intranet. The system regularly pulled patient demographic details such as name, age, medical record number, and location from our electronic medical record through a 1‐way interface. Information from this communication system was not considered part of the medical record but was retrievable.

The system was introduced as the new standard method of communication for nurses to reach physicians for all of the general internal medicine wards and for all medical teams at site 1 on May 2, 2011 and site 2 on June 6, 2011. The system replaced a text‐based Web‐paging system and supplemented the numeric pager carried by residents. Initial training of a half hour was provided to all nurses and residents.

Message Analysis for Usage Statistics

We analyzed messages created and sent via the CM system from May 2011 until August 2012. The extracted message information included date and time sent, issue, level of urgency, response type requested, roles of clinicians involved from the associated team, hospital site (senders and receivers), and message details. The following inclusion criteria were used for the analyses: (1) the senders and receivers of the messages could not be CM support staff, and (2) the messages sent were intended for the team smartphones used by the respective medical teams, not individual clinicians. Descriptive statistics and frequency analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and IBM SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Survey

Development of the Survey

We used standard methods to develop a survey to assess staff perceptions on the impact of the new communication system. Relevant questionnaire items were compiled from a systematic review of the literature for communication surveys and communication issues that included the following domains: efficiency, accountability, accuracy, collaboration, timeliness, richness of the communication medium, and impact on interprofessional relationships and verbal communication.[10, 14, 15] We carried out pilot testing with 5 nurses and physicians, and modified the questionnaires based on their feedback.

Sampling and Data Collection of the Survey

Survey participants consisted of 2 groups of clinicians: (1) medical trainees that included medical residents, medical interns, and clinical fellows, and (2) nursing staff that included part‐time and full‐time nurses. To qualify for inclusion, participants had to have used the CM system for at least a month prior to administration of the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Responses were recorded into an Excel spreadsheet that was imported into SPSS for analysis. Categorical variables were described using proportions. Survey comments were grouped into common themes, and themes mentioned by more than 1 respondent were reported.

RESULTS

Usage Analysis

A total of 60,969 messages were sent using CM between May 2, 2011 and August 19, 2012. On average, a team would receive 14.8 messages per day. Of all messages, 76.5% requested a text reply, 7.7% requested a call‐back, and 15.7% did not request a response. More than two‐thirds of messages at both hospitals were sent as immediate. Of the nonurgent messages, 86% were not replied to within the desired time, requiring a repeat message to be sent. Examples of different types of messages are shown in Table 1.

| Sender | Issue | Details | Priority | Desired Response Type | Time Created | Time Sent | Reply | Time Replied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Nurse | Vital sign | Pt's BP is 182/95, HR is 108 now. Previous at 0800 was 165/78; HR was 99. PT is not on antihypertensive meds. | Allow time to respond (23:00) | Text reply | 21:43 | 23:02 | OK. Will assess. | 23:03 |

| Nurse | NG tube | NG tube is in place. Can you please enter portable chest x‐ray to check placement ASAP? | Immediate | Text reply | 16:58 | 16:58 | Will do. | 17:00 |

| Nurse | Bloodwork | Pt creat=216. Pt has NS @ 75 cc/hr. Pt has noted crackles throughout lung fields and has productive cough; eating and drinking well. Would you like it continued as well? Pt O2Sat 93% RA; would you like 4 L of O2 continued? Pls call for telephone order. | Immediate | Call back | 12:53 | 13:04 | Dealt with it on phone. | 13:05 |

| Nurse | Pain control | Hello! Pt has been getting 1 mg hydromorphone IV q 1 hr and pain is still not controlled. Pt remains awake and alert. Thanks! | Immediate | Info only | 15:41 | 15:41 | Thank you. | 15:42 |

For messages requesting a text reply, 8.6% did not receive a reply. The median response time was 2.3 minutes (interquartile range of 5.8 minutes), but some messages did not receive a response even after a week, which skewed the distribution of response times. For those messages that did receive a reply, 68.9% of them were responded to within 5 minutes, and 84.5% were responded to within 15 minutes. Messages were predominantly received between 9 am and midnight (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). Because the sending of some messages was delayed, there appeared to be fewer messages received during protected educational times (89 am and 121 pm) as well as between midnight and 7 am compared to other times.

Survey Results

Between April 2013 and June 2013, 82 of 86 medical trainees (95.3%) and 83 of 116 nurses (71.6%) completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 81.7%. Clinicians perceived that CM appeared to have a positive impact on efficiency. In particular, 82.8% of physicians and 78.3% of nurses agreed or strongly agreed that CM helped speed up daily work tasks (Table 2). The majority of physicians and nurses agreed that the system increased accountability, increased timeliness of communication, and improved interprofessional relationships. It was not seen to be effective for communicating complex patient issues.

| No. of Subitems in Survey | Physician (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=82 | Nurse (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=83 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Positive impact on efficiency. | 7 | 58.9% | 66.6% |

| The CM system helps speed up my daily work tasks. | 82.8% | 78.3% | |

| Positive impact on physician‐nurse collaboration. | 6 | 55.3% | 58.5% |

| The CM system increases the amount of communication between nurses and physicians. | 50.6% | 67.1% | |

| Improved timeliness of communication. | 5 | 54.2% | 50.5% |

| Communication through the CM system helps me resolve patient issues within the appropriate time frames. | 66.7% | 55.6% | |

| Increased accountability. | 2 | 67.1% | 73.2% |

| Improved accuracy of communications. | 3 | 41.6% | 50.7% |

| Improved interprofessional relationships. | 2 | 62.2% | 53.6% |

| Increased verbal communications. | 2 | 35.1% | 25.3% |

| Richness of the communication medium. | 6 | 40.7% | 48.3% |

| I find the CM system useful for communicating complex patient issues. | 35.8% | 26.3% | |

| I would prefer CM over standard hospital communication methods such as numeric paging. | 1 | 68.3% | 76.5% |

| I enjoy using the CM system for clinical communication on the wards. | 1 | 63.0% | 79.0% |

| Communication through the CM system helps to reduce interruptions for physicians. | 1 | 45.7% | |

Survey comments revealed that nurses perceived a lack of desired response, whereas physicians noted being interrupted with low‐value information through the system (Table 3). Both commented that further functionality, such as an active message stream, would be of benefit. Difficulty in communicating complex issues was also noted.

| Issue | Occurrences | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | RN | Total | ||

| ||||

| Lack of response | 1 | 10 | 11 | It depends if they respond quickly or not. A few times I send the 2nd message to remind them of the issue. I also spend more time to check if they answer it or not. I even call their Blackberries at last to get a response. |

| Message stream | 3 | 4 | 7 | I wish that I could see follow‐up messages after my initial reply (ie, it would be nice to have an open message stream). |

| Difficult to communicate complex issues | 1 | 5 | 6 | Difficult to communicate complex issues. Takes a lot of time to respond, and it becomes inefficient when responding to nonurgent CM because it interrupts workflow. |

| Many messages are low‐value interrupts | 3 | 0 | 3 | CM is useful for handover between clinicians, but often it slows down the clinician when they are used for information‐related low‐value/noncritical messages between nurses and clinicians |

| Lack of detailed response | 0 | 3 | 3 | Specific messages regarding response to care is required most times. For example, acknowledged is not a favorable response. |

| Technical issues | 2 | 0 | 2 | I find CM very useful. We have had multiple issues with our Blackberry this month, and CM was not working. When it is up and running, however, it is a wonderful tool. |

| Discrepancy in perceived urgency | 2 | 0 | 2 | Discrepancy between what nurses find urgent and what we find urgent. |

DISCUSSION

We describe an implementation of a system to improve clinical communication in hospitals. The system was highly used and was perceived to improve communication by both nurses and physicians. Specifically, users found that the system increased efficiency, accountability, timeliness, and collaboration, but that there were issues with message clarity for complex medical issues.

Other systems and approaches have been implemented to improve communication. These included the use of alphanumeric pagers, e‐mail, secure texting, and smartphones. There is evidence that more advanced systems can improve efficiency for senders.[16] A recent randomized trial of secure text messaging found that it was perceived to be more efficient than paging, but overall usage was low and inconsistent.[8] There is also evidence that smartphones may increase interruptions, worsen interprofessional relationships, and cause issues with professional behavior.[10] Unfortunately, there are a limited number of interventions that improve communication, with some improving efficiency but none demonstrating improved patient‐oriented outcomes.[16, 17] This study evaluated a novel system, with functionality to link communication to patients, and created a system that aligned with the workflow of the clinicians. Messages were linked to the patient, not the sender or receiver, so other clinicians in the patient's circle of care could easily view the communication. Moreover, the system was designed to improve message response rates and allow for nonurgent messages.

Our communication system uses standard, commercially available components (smartphones, SMS), and relatively basic functionality (handover, secure messaging). Important findings are that the current system of paging can be transformed to a more efficient system that users will readily adopt. We found positive effects with components of the system. It appeared to improve efficiency and increase accountability. Accountability is crucial and moves from undocumented conversation to fully documented details of interactions. This can be used for both incident review and to review for quality improvement.

Using the system, physicians perceived that they were bothered by low‐value information, whereas nurses perceived a lack of response, and both found that the system was not ideal for complex messages. The mismatch between what physicians and nurses perceive as important has been attributed to their different timeframes and context.[18] For nurses with an upcoming change of shift, they wanted resolution of issues before handover. A physician on a different ward may not appreciate the context of a nurse having to directly interact with an irate family member. These different perceptions likely contributed to the lack of response to 8.6% of text messages. This is still better than other systems, such as paging, which can be as high as 33%.[10] For nonurgent items, clinicians would ideally check and clear items regularly from the system using a desktop computer, responding within the allotted timeframe. Unfortunately, this never became part of routine physician workflow, likely due to their busy workload, so many physicians would only respond when items became overdue. However, having a method to deal with nonurgent messages may have prevented some interruptions during protected educational times of trainees. The system was also not ideal for urgent or complex items. Complex items can be difficult to convey using the rarified communication medium of text messages.[19, 20] Urgent or complex issues are likely best resolved with a face‐to‐face or telephone conversation.

There are several limitations in our study that should be considered when interpreting the results. It is a study of usage and perceptions after implementation. Although more rigorous study is required to evaluate the effects, we see this as a first step in process improvement. Future research should measure the impact on improving patient care of this system and on patient outcomes such as adverse events. The study and intervention was limited to general internal medicine wards in 2 academic hospital settings where there are frequent rotations of medical personnel. The findings may not be generalizable to other hospital settings.

Future directions should be to further improve on the communication system and to educate and train staff on how to effectively communicate. Survey results showed that although users perceived increased efficiency, there was still significant opportunity to improve. One way to improve would be to have a mobile application in which physicians can easily review nonurgent items. Improvements could also be realized by educating clinicians on the use of the system and providing immediate feedback. Providing feedback to physicians on how well they respond could address nurses' issues around lack of timely response. By creating consensus between nurses and physicians on what is of high and low value to communicate could increase satisfaction for all users.

In summary, we present the usage and perceptions of a system designed to improve hospital communication. We found that there was high uptake, and that users perceived it to improve efficiency, collaboration, and accountability, but it may not be useful for communicating complex issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the nurses, physicians, residents, and other health professions on the general internal medicine ward for their patience and support as we continue to try to innovate. The authors also acknowledge the members of the information systems department (Shared Information Management Systems, University Health Network) who helped to support the Communication System, and the software developer, QRS, that helped to codevelop the software system.

Disclosures: The hospital was in a codevelopment agreement that has since terminated. No researcher or hospital received any funds from private industry for any purpose including personal or research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Previous studies have advocated the importance of effective communication between clinicians as a critical component in the provision of high‐quality patient care.[1, 2, 3, 4] There is increasing interest in the use of information and communication technologies to improve how clinicians communicate in hospital settings. A number of hospitals have implemented different solutions to improve communication. These solutions include alphanumeric pagers,[5] smartphones,[6] e‐mail,[7] secure text messaging,[8] and a Web‐based interdisciplinary communication tool.[9]

These systems have different limitations that render them inefficient and likely inhibit collaborative care. Current systems, such as pagers, rely on the sender to ensure the message was received and are successful in delivering messages approximately 67% of the time.[5, 9, 10] Although alphanumeric pagers and secure text messaging can increase the likelihood of delivery, these messages are often isolated and not easily viewable by the whole care team.[11] Improved systems should also reduce unnecessary interruptions by providing support for both urgent and delayed messages. Finally, messages should be stored and retrievable to enable increased accountability and allow for review for quality improvement initiatives.

It is also important to consider the unintended consequences of technology implementations.[12] Moving communication to text messages and smartphones has the potential to reduce interprofessional relations and can increase confusion if used for complex issues.[10, 13] In this article, we present a system designed to improve interprofessional communication on general internal medicine wards by incorporating these desired features and describe the usage and attitudes toward the system, specifically assessing for effects on multiple domains including efficiency, interprofessional collaboration, and relationships.

METHODS

Research Question

Will nurses and physicians use a system designed to improve interprofessional communication and will they perceive it to be effective and improve workflow?

Setting

The study took place on the general internal medicine wards at Toronto General Hospital and Toronto Western Hospital, 2 large academic teaching hospitals. There are several general internal medicine wards at each site with approximately 80 beds at each site. At each site there are 4 clinical teaching units and 1 hospitalist team. The study was approved by the research ethics board at the University Health Network.

Intervention

To address issues with communication, we developed a systemClinical Message (CM)that included 2 main components: a physician handover tool and secure messaging module. The focus of CM was to improve communication and information flow among different healthcare providers (physicians, nurses, pharmacists, social workers and therapists) through a secure, shared platform.

Physician Handover

The physician handover tool was designed to facilitate the physician handover process at shift change and is used as a patient rounding tool for day‐to‐day management of patients. It is also accessed by nurses and other clinicians to view the physicians' notes and to stay informed on the overall care plan. The tool contains standard elements including a list of patients with the following information on each patient: demographics, diagnosis, code status, medical history, active issues, and discharge plans (Figure 1).

Secure Messaging

Secure messaging was designed around our dominant communication: nurses sending messages to physicians who would then respond. Nurses and other health professionals sent messages to the medical teams by accessing CM, selecting the appropriate patient, and filling out a message template. The system automatically populated the To field with the team assigned to the selected patient. Messaging for each team was centralized around a single team smartphone that was carried 24 hours a day, 7 days a week by a physician on that team. This removed the guesswork of trying to identify the individual physician responsible for that patient. For each message, a subject or issue and content were entered (Figure 2). Logic was also incorporated to reduce the amount of unnecessary interruptions. Senders would choose to send the message immediately as an interrupt message (urgent) for urgent/time sensitive issues or as an allow time to respond message (delayed). For the latter, the message was posted to the system where physicians could check and answer them. Interrupt messages were sent to the team smartphone using the Short Message Service (SMS) protocol. To try and ensure the communication loop on any issues was closed, when a message requested a response and did not receive it, the system sent another message. For urgent messages, a repeat message was initiated after 15 minutes. For delayed messages, the sender defined when they needed a response, typically within 2 to 8 hours. Senders were also able to select the mode of response that would best meet their needs from a workflow perspective: call back, text reply, or to specify that a reply was not required. Senders were also able to verify if the messages were received by the physician's smartphone. Physicians could view the messages within CM and reply. For messages that went to their team smartphone, physicians could respond from the smartphone through a secure Web link.

Because the messages were linked to the patients, they were visible to the entire care team, not just the message sender and recipient. If the care of the patient was transferred from 1 clinician to the next, the new clinician could easily review prior messages to understand recent patient events. The system was accessible through a browser on the intranet. The system regularly pulled patient demographic details such as name, age, medical record number, and location from our electronic medical record through a 1‐way interface. Information from this communication system was not considered part of the medical record but was retrievable.

The system was introduced as the new standard method of communication for nurses to reach physicians for all of the general internal medicine wards and for all medical teams at site 1 on May 2, 2011 and site 2 on June 6, 2011. The system replaced a text‐based Web‐paging system and supplemented the numeric pager carried by residents. Initial training of a half hour was provided to all nurses and residents.

Message Analysis for Usage Statistics

We analyzed messages created and sent via the CM system from May 2011 until August 2012. The extracted message information included date and time sent, issue, level of urgency, response type requested, roles of clinicians involved from the associated team, hospital site (senders and receivers), and message details. The following inclusion criteria were used for the analyses: (1) the senders and receivers of the messages could not be CM support staff, and (2) the messages sent were intended for the team smartphones used by the respective medical teams, not individual clinicians. Descriptive statistics and frequency analysis were performed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and IBM SPSS (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Survey

Development of the Survey

We used standard methods to develop a survey to assess staff perceptions on the impact of the new communication system. Relevant questionnaire items were compiled from a systematic review of the literature for communication surveys and communication issues that included the following domains: efficiency, accountability, accuracy, collaboration, timeliness, richness of the communication medium, and impact on interprofessional relationships and verbal communication.[10, 14, 15] We carried out pilot testing with 5 nurses and physicians, and modified the questionnaires based on their feedback.

Sampling and Data Collection of the Survey

Survey participants consisted of 2 groups of clinicians: (1) medical trainees that included medical residents, medical interns, and clinical fellows, and (2) nursing staff that included part‐time and full‐time nurses. To qualify for inclusion, participants had to have used the CM system for at least a month prior to administration of the questionnaire.

Data Analysis

Responses were recorded into an Excel spreadsheet that was imported into SPSS for analysis. Categorical variables were described using proportions. Survey comments were grouped into common themes, and themes mentioned by more than 1 respondent were reported.

RESULTS

Usage Analysis

A total of 60,969 messages were sent using CM between May 2, 2011 and August 19, 2012. On average, a team would receive 14.8 messages per day. Of all messages, 76.5% requested a text reply, 7.7% requested a call‐back, and 15.7% did not request a response. More than two‐thirds of messages at both hospitals were sent as immediate. Of the nonurgent messages, 86% were not replied to within the desired time, requiring a repeat message to be sent. Examples of different types of messages are shown in Table 1.

| Sender | Issue | Details | Priority | Desired Response Type | Time Created | Time Sent | Reply | Time Replied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| Nurse | Vital sign | Pt's BP is 182/95, HR is 108 now. Previous at 0800 was 165/78; HR was 99. PT is not on antihypertensive meds. | Allow time to respond (23:00) | Text reply | 21:43 | 23:02 | OK. Will assess. | 23:03 |

| Nurse | NG tube | NG tube is in place. Can you please enter portable chest x‐ray to check placement ASAP? | Immediate | Text reply | 16:58 | 16:58 | Will do. | 17:00 |

| Nurse | Bloodwork | Pt creat=216. Pt has NS @ 75 cc/hr. Pt has noted crackles throughout lung fields and has productive cough; eating and drinking well. Would you like it continued as well? Pt O2Sat 93% RA; would you like 4 L of O2 continued? Pls call for telephone order. | Immediate | Call back | 12:53 | 13:04 | Dealt with it on phone. | 13:05 |

| Nurse | Pain control | Hello! Pt has been getting 1 mg hydromorphone IV q 1 hr and pain is still not controlled. Pt remains awake and alert. Thanks! | Immediate | Info only | 15:41 | 15:41 | Thank you. | 15:42 |

For messages requesting a text reply, 8.6% did not receive a reply. The median response time was 2.3 minutes (interquartile range of 5.8 minutes), but some messages did not receive a response even after a week, which skewed the distribution of response times. For those messages that did receive a reply, 68.9% of them were responded to within 5 minutes, and 84.5% were responded to within 15 minutes. Messages were predominantly received between 9 am and midnight (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). Because the sending of some messages was delayed, there appeared to be fewer messages received during protected educational times (89 am and 121 pm) as well as between midnight and 7 am compared to other times.

Survey Results

Between April 2013 and June 2013, 82 of 86 medical trainees (95.3%) and 83 of 116 nurses (71.6%) completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 81.7%. Clinicians perceived that CM appeared to have a positive impact on efficiency. In particular, 82.8% of physicians and 78.3% of nurses agreed or strongly agreed that CM helped speed up daily work tasks (Table 2). The majority of physicians and nurses agreed that the system increased accountability, increased timeliness of communication, and improved interprofessional relationships. It was not seen to be effective for communicating complex patient issues.

| No. of Subitems in Survey | Physician (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=82 | Nurse (% Agree, Strongly Agree), n=83 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Positive impact on efficiency. | 7 | 58.9% | 66.6% |

| The CM system helps speed up my daily work tasks. | 82.8% | 78.3% | |

| Positive impact on physician‐nurse collaboration. | 6 | 55.3% | 58.5% |

| The CM system increases the amount of communication between nurses and physicians. | 50.6% | 67.1% | |

| Improved timeliness of communication. | 5 | 54.2% | 50.5% |

| Communication through the CM system helps me resolve patient issues within the appropriate time frames. | 66.7% | 55.6% | |

| Increased accountability. | 2 | 67.1% | 73.2% |

| Improved accuracy of communications. | 3 | 41.6% | 50.7% |

| Improved interprofessional relationships. | 2 | 62.2% | 53.6% |

| Increased verbal communications. | 2 | 35.1% | 25.3% |

| Richness of the communication medium. | 6 | 40.7% | 48.3% |

| I find the CM system useful for communicating complex patient issues. | 35.8% | 26.3% | |

| I would prefer CM over standard hospital communication methods such as numeric paging. | 1 | 68.3% | 76.5% |

| I enjoy using the CM system for clinical communication on the wards. | 1 | 63.0% | 79.0% |

| Communication through the CM system helps to reduce interruptions for physicians. | 1 | 45.7% | |

Survey comments revealed that nurses perceived a lack of desired response, whereas physicians noted being interrupted with low‐value information through the system (Table 3). Both commented that further functionality, such as an active message stream, would be of benefit. Difficulty in communicating complex issues was also noted.

| Issue | Occurrences | Example | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MD | RN | Total | ||

| ||||

| Lack of response | 1 | 10 | 11 | It depends if they respond quickly or not. A few times I send the 2nd message to remind them of the issue. I also spend more time to check if they answer it or not. I even call their Blackberries at last to get a response. |

| Message stream | 3 | 4 | 7 | I wish that I could see follow‐up messages after my initial reply (ie, it would be nice to have an open message stream). |

| Difficult to communicate complex issues | 1 | 5 | 6 | Difficult to communicate complex issues. Takes a lot of time to respond, and it becomes inefficient when responding to nonurgent CM because it interrupts workflow. |

| Many messages are low‐value interrupts | 3 | 0 | 3 | CM is useful for handover between clinicians, but often it slows down the clinician when they are used for information‐related low‐value/noncritical messages between nurses and clinicians |

| Lack of detailed response | 0 | 3 | 3 | Specific messages regarding response to care is required most times. For example, acknowledged is not a favorable response. |

| Technical issues | 2 | 0 | 2 | I find CM very useful. We have had multiple issues with our Blackberry this month, and CM was not working. When it is up and running, however, it is a wonderful tool. |

| Discrepancy in perceived urgency | 2 | 0 | 2 | Discrepancy between what nurses find urgent and what we find urgent. |

DISCUSSION

We describe an implementation of a system to improve clinical communication in hospitals. The system was highly used and was perceived to improve communication by both nurses and physicians. Specifically, users found that the system increased efficiency, accountability, timeliness, and collaboration, but that there were issues with message clarity for complex medical issues.

Other systems and approaches have been implemented to improve communication. These included the use of alphanumeric pagers, e‐mail, secure texting, and smartphones. There is evidence that more advanced systems can improve efficiency for senders.[16] A recent randomized trial of secure text messaging found that it was perceived to be more efficient than paging, but overall usage was low and inconsistent.[8] There is also evidence that smartphones may increase interruptions, worsen interprofessional relationships, and cause issues with professional behavior.[10] Unfortunately, there are a limited number of interventions that improve communication, with some improving efficiency but none demonstrating improved patient‐oriented outcomes.[16, 17] This study evaluated a novel system, with functionality to link communication to patients, and created a system that aligned with the workflow of the clinicians. Messages were linked to the patient, not the sender or receiver, so other clinicians in the patient's circle of care could easily view the communication. Moreover, the system was designed to improve message response rates and allow for nonurgent messages.

Our communication system uses standard, commercially available components (smartphones, SMS), and relatively basic functionality (handover, secure messaging). Important findings are that the current system of paging can be transformed to a more efficient system that users will readily adopt. We found positive effects with components of the system. It appeared to improve efficiency and increase accountability. Accountability is crucial and moves from undocumented conversation to fully documented details of interactions. This can be used for both incident review and to review for quality improvement.

Using the system, physicians perceived that they were bothered by low‐value information, whereas nurses perceived a lack of response, and both found that the system was not ideal for complex messages. The mismatch between what physicians and nurses perceive as important has been attributed to their different timeframes and context.[18] For nurses with an upcoming change of shift, they wanted resolution of issues before handover. A physician on a different ward may not appreciate the context of a nurse having to directly interact with an irate family member. These different perceptions likely contributed to the lack of response to 8.6% of text messages. This is still better than other systems, such as paging, which can be as high as 33%.[10] For nonurgent items, clinicians would ideally check and clear items regularly from the system using a desktop computer, responding within the allotted timeframe. Unfortunately, this never became part of routine physician workflow, likely due to their busy workload, so many physicians would only respond when items became overdue. However, having a method to deal with nonurgent messages may have prevented some interruptions during protected educational times of trainees. The system was also not ideal for urgent or complex items. Complex items can be difficult to convey using the rarified communication medium of text messages.[19, 20] Urgent or complex issues are likely best resolved with a face‐to‐face or telephone conversation.

There are several limitations in our study that should be considered when interpreting the results. It is a study of usage and perceptions after implementation. Although more rigorous study is required to evaluate the effects, we see this as a first step in process improvement. Future research should measure the impact on improving patient care of this system and on patient outcomes such as adverse events. The study and intervention was limited to general internal medicine wards in 2 academic hospital settings where there are frequent rotations of medical personnel. The findings may not be generalizable to other hospital settings.

Future directions should be to further improve on the communication system and to educate and train staff on how to effectively communicate. Survey results showed that although users perceived increased efficiency, there was still significant opportunity to improve. One way to improve would be to have a mobile application in which physicians can easily review nonurgent items. Improvements could also be realized by educating clinicians on the use of the system and providing immediate feedback. Providing feedback to physicians on how well they respond could address nurses' issues around lack of timely response. By creating consensus between nurses and physicians on what is of high and low value to communicate could increase satisfaction for all users.

In summary, we present the usage and perceptions of a system designed to improve hospital communication. We found that there was high uptake, and that users perceived it to improve efficiency, collaboration, and accountability, but it may not be useful for communicating complex issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the nurses, physicians, residents, and other health professions on the general internal medicine ward for their patience and support as we continue to try to innovate. The authors also acknowledge the members of the information systems department (Shared Information Management Systems, University Health Network) who helped to support the Communication System, and the software developer, QRS, that helped to codevelop the software system.

Disclosures: The hospital was in a codevelopment agreement that has since terminated. No researcher or hospital received any funds from private industry for any purpose including personal or research. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–376.

- , , , et al. Gaps in pediatric clinician communication and opportunities for improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(5):43–54.

- , , , , . Quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1996;164(12):754.

- , , , . Implementation and evaluation of an alphanumeric paging system on a resident inpatient teaching service. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E34–E40.

- , , , et al. Demonstrating the BlackBerry as a clinical communication tool: a pilot study conducted through the Centre for Innovation in Complex Care. Healthc Q. 2008;11(4):94–98.

- , , , . The use of wireless email to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):705–713.

- , , , , , . Smarter hospital communication: secure smartphone text messaging improves provider satisfaction and perception of efficacy, workflow. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):573–578.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , , , et al. The intended and unintended consequences of communication systems on general internal medicine inpatient care delivery: a prospective observational case study of five teaching hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(4):766–777.

- , , , et al. Improving hospital care and collaborative communications for the 21st century: key recommendations for general internal medicine. Interact J Med Res. 2012;1(2):e9.

- , , , , , . Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):82–90.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- , , , , . Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse‐physician questionnaire. Med Care. 1991;29(8):709–726.

- . Impact of communication medium on task performance and satisfaction: an examination of media‐richness theory. Inform Manag. 1999;35:295–312.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):589–597.

- , , , et al. Perceptions of urgency: defining the gap between what physicians and nurses perceive to be an urgent issue. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(5):378–386.

- , , , , , . Short message service or disService: issues with text messaging in a complex medical environment. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(4):278–284.

- , , . Instant messaging at the hospital: supporting articulation work? Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(9):753–761.

- . When conversation is better than computation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2000;7(3):277–286.

- , , , et al. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):370–376.

- , , , et al. Gaps in pediatric clinician communication and opportunities for improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2008;30(5):43–54.

- , , , , . Quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1996;164(12):754.

- , , , . Implementation and evaluation of an alphanumeric paging system on a resident inpatient teaching service. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):E34–E40.

- , , , et al. Demonstrating the BlackBerry as a clinical communication tool: a pilot study conducted through the Centre for Innovation in Complex Care. Healthc Q. 2008;11(4):94–98.

- , , , . The use of wireless email to improve healthcare team communication. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16(5):705–713.

- , , , , , . Smarter hospital communication: secure smartphone text messaging improves provider satisfaction and perception of efficacy, workflow. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(9):573–578.

- , , , , . Beyond paging: building a web‐based communication tool for nurses and physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(1):105–110.

- , , , et al. The intended and unintended consequences of communication systems on general internal medicine inpatient care delivery: a prospective observational case study of five teaching hospitals. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2013;20(4):766–777.

- , , , et al. Improving hospital care and collaborative communications for the 21st century: key recommendations for general internal medicine. Interact J Med Res. 2012;1(2):e9.

- , , , , , . Anticipating and addressing the unintended consequences of health IT and policy: a report from the AMIA 2009 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(1):82–90.

- , , , et al. An evaluation of the use of smartphones to communicate between clinicians: a mixed‐methods study. J Med Internet Res. 2011;13(3):e59.

- , , , , . Organizational assessment in intensive care units (ICUs): construct development, reliability, and validity of the ICU nurse‐physician questionnaire. Med Care. 1991;29(8):709–726.

- . Impact of communication medium on task performance and satisfaction: an examination of media‐richness theory. Inform Manag. 1999;35:295–312.

- , , , et al. Effects of clinical communication interventions in hospitals: a systematic review of information and communication technology adoptions for improved communication between clinicians. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(11):723–732.

- , , , et al. Provider‐to‐provider electronic communication in the era of meaningful use: a review of the evidence. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):589–597.

- , , , et al. Perceptions of urgency: defining the gap between what physicians and nurses perceive to be an urgent issue. Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(5):378–386.

- , , , , , . Short message service or disService: issues with text messaging in a complex medical environment. Int J Med Inform. 2014;83(4):278–284.

- , , . Instant messaging at the hospital: supporting articulation work? Int J Med Inform. 2013;82(9):753–761.

© 2014 Society of Hospital Medicine