User login

Many clinicians continue to think that delirium or acute confusion is inevitable, untreatable, and harmless. However, nothing could be further from the truth.1 Delirium is a common and costly clinical syndrome that plagues a large percentage of older adults in a variety of settings. Numerous clinical studies conducted over the past 20 years have validated a high incidence of delirium in acute care hospitals.2-5 Reported rates of delirium among veteran and nonveteran populations vary widely, from 20% to 80%, but even these rates may reflect underrecognition and underreporting.6

Veterans with delirium pose a unique challenge to clinicians and health care systems because they often concurrently experience dementia, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and delirium. This complex syndrome caused by a myriad of environmental, physiologic, and psychological factors has been associated with profoundly poor clinical outcomes, including increased institutionalization, hospital length of stay, medication use, restraint use, falls, and mortality.3,7,8

Financial costs associated with delirium have been estimated at between $38 billion and $152 billion per year.9 In addition, this syndrome is costly in human resource expenditures, including increased burden on family members and the need for additional care providers, such as “sitters.” Families and clinicians report increased burden and stress in their interactions with these patients.10-12 Mounting evidence exists that some people with delirium never return to baseline cognitive function after even a single episode of delirium.1,8 Unfortunately, many clinicians do not recognize the seriousness of acute confusion.

Clinical practices related to routine screening for delirium vary widely. Although the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) screening tool has high sensitivity and specificity, only 17% of hospitals consistently use this tool in clinical practice.2,6,13,14 According to a survey by Ely and colleagues, physicians reported being aware of delirium but inconsistently applying treatment protocols in clinical practice.2 Nurses noted similar difficulties in consistently screening patients and using delirium management protocols.15 Given the high incidence of delirium and its associated morbidity, including long-term cognitive impairment and human and financial costs, there is an urgent need to implement programs that enhance delirium prevention, timely recognition, and effective management to improve patient outcomes and address caregiver burden.

Over the past decade, educational strategies for improving delirium prevention, recognition, and management have included didactic education, consultation, and use of protocols.2,3,5,16 Bedside mentoring, implementation of protocols, and other interventions have been proposed as well.16,17 Several program models, including consultation by psychiatrists or psychiatric advanced practice nurses, have been implemented to increase detection and treatment of delirium.2,3,5,15 These pilot programs have been successful to varying degrees but in general have not shown independent effects beyond intervention or significantly increased recognition and management of adverse consequences for most patients. The cause of these outcomes seem to be multifactorial, but the complexity of the syndrome is part of the problem.18-20

Other possible barriers to change regarding delirium-related issues in clinical practice are lack of knowledge and skills and individual attitudes.20-22 Continuing evidence exists that clinicians feel ill-prepared to help delirious patients and frustrated enough to resort to using restraints and medication as first-line treatment.17 Yanamadala and colleagues reviewed 26 studies that identified strategies for delirium education.23 Most of the studies reported on didactic teaching methods that included information on resources. Only 1 study with nursing students reported using actors for simulation training. The programs most successful in improving knowledge, skills, attitudes, practice changes, and patient outcomes seemed to be those that used multiple educational methods, including information dissemination, use of guidelines and protocols, and peer and expert feedback.

This finding is consistent with the report that didactic learning alone, though improving competency, is less likely to change behavior or improve outcomes.24 A constellation of didactic education, mentoring, use of protocols to target high-risk patients, and a therapeutic environment has helped to reduce delirium incidence.4,25,26 Rudolph and colleagues found an association between multimodal education (risk assessment, sensory improvement, sleep promotion) and shorter hospital stays and less use of restraints.27 In clinical practice,however, implementation of evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions, such as enhanced communication, mobility, nutrition, and meaningful activities, continues to lag despite education.28,29

Multimodal Education

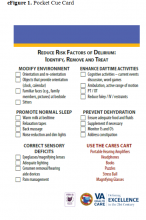

To address these gaps in knowledge and skills, a multidisciplinary delirium resource team at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio developed a multimodal educational program incorporating simulation. The team of physicians, nurses, care coordinators, and social workers met regularly and developed interventions, educational materials, cue cards (eFigure 1), sense-enhancing aids (hearing amplifiers, puzzles, books, music CDs, prism glasses), clinical protocols, and delirium resources, such as CARES (Confusion Assessment Resource Enhancement Supplies) activity carts.

The CARES carts are small, rolling wooden carts stocked with various resources that focus on comfort and entertainment. The carts hold guided imagery CDs and Playaways (small audio players that come with ear buds for individual use and preloaded with a specific guided imagery session). The carts also hold books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthful snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player.

Bedside mentoring continued throughout this quality improvement (QI) project, and a CARES teaching tool kit was developed. This kit, which continues to be used, includes videos and webinars for professionals and family caregivers; delirium pocket cue cards for physicians, nurses, aides, and sitters; a list of patient diversion supplies; and a family brochure. Delirium resource team members continue to provide the health care team with education and support. Given the emphasis on clinicians and patient outcomes in intensive care units (ICUs), the teaching tool kit is a valuable guide for assessing and treating patients with delirium during rounds and consultations.

Simulation

Using a simulation center and standardized patients (SPs), teams of interdisciplinary care providers practiced communication techniques and recommended treatment strategies with the help of a delirium coach. Sessions were videotaped. This intervention, which used simulation training, was supported by VA grant T-21, to reduce institutionalization and promote patient-centered care.

In a clinical context, simulation involves activities that mimick the reality of the clinical environment, including physical symptoms, communication patterns, and critical decision making. Trained SPs have the unique advantage of providing interactive practice and immediate feedback in a safe, controlled setting.30

Standardized patient programs provide learners with real-life interactions for the development and practice of interpersonal communication and clinical skills. In a laboratory setting, SP programs use role-play scenarios that allow learners to practice complex assessment and communication skills. Standardized patients are effective in teaching clinical, interviewing, and communication skills to learners from a variety of disciplines, including medicine, nursing, dental, and law.31 Standardized patients also provide a safe, supportive environment conducive to learning and standardized assessment.

Standardized patients can serve as practice models and participate in sophisticated assessment and feedback of learners’ abilities and services. Interacting with SPs gives learners a chance to practice clinical and interpersonal skills with an emphasis on communication before meeting actual patients. After interacting with an SP, a learner receives feedback from a preceptor and/or the learner’s peers. The SP also may be asked to provide brief feedback—a component of the SP training process. Allowing time for feedback is an integral part of student learning.

For this QI project, the delirium team used the Mt. Sinai Skills and Simulation Center at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. The facility focuses on creative, innovative continuing learning for health care providers at all levels and is certified by the American College of Surgeons as a level 1 Comprehensive Accredited Education Institute.

After a literature review and several brainstorming sessions, the delirium team tailored case studies to veterans to simulate the intervention and train SPs for the delirium program. During training, SPs reviewed scenarios, engaged in practice sessions, and answered questions. Several SPs were familiar with the behavior of delirious patients from personal experience.

The goals of the program were to increase knowledge of delirium signs and symptoms as a medical condition that requires immediate attention; increase competency in administering CAM and in documenting its results; increase interdisciplinary communication; and increase knowledge using nonpharmacologic interventions for sensory enhancement and agitation. Enhanced interdisciplinary communication was accomplished during the simulation by assigning individuals from different disciplines to work in teams. To maximize the use of resources and limit participants’ time away from the clinical area, the administration planned and supported a daylong program that included didactic education, videos, group work sessions, and the simulation sessions with resource team members as coaches.

Methods

All participants attended an hour-long introductory didactic lecture together. Then, they were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 remaining 45-minute training sessions. Each participant attended a session that combined a video and a case study; a session of role-playing with group discussion; and 2 simulation scenario sessions. Concurrent training sessions were needed to facilitate having all 100 attendees participate within 6 hours. Attendees were multidisciplinary providers from various non-ICU medical/surgical units and outpatient geriatric clinics. They rotated among sessions to accommodate all participants.

For the simulation scenarios, 8 simulation rooms were used over 2 periods—for 16 simulation sessions total. Participants were randomly assigned to multidisciplinary groups that worked in teams to assess and recommend care and treatments for SPs who were stimulating delirium. During the simulation, delirium coaches used cue cards and verbal hints to direct teams (Simulation Exercise). After the session, participants received verbal and

Outcomes

The impact of this multimodal intervention was measured in a variety of ways—with preintervention and postintervention knowledge tests, postsimulation surveys, program surveys, and patient chart reviews. Simulation sessions had 100 attendees, including mentors (interdisciplinary resource team), champions, and nursing staff from various hospital units. Champions represented multiple disciplines and had varying levels of experience. Most of the participants were nurses (62%), followed by social workers (12%), nursing assistants (12%), psychologists (6%), and others (11%). Participants’ years of experience were < 1 year (6%), 1 to 5 years (21%), 6 to 10 years (21%), and > 10 years (52%).

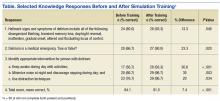

Mean knowledge survey score was 84% before training and 92% after training. Recognition of delirium as a medical emergency requiring immediate follow-up was increased (P = .02), as was knowledge about delirium management, as in increasing daytime activities (P < .001) and using distraction techniques (P = .03) (Table).

More than 94% of participants said the simulation training fulfilled their education needs. More than 80% reported using the information from the delirium workshop in their practice. In reviewing the techniques presented during the workshop, participants reported that they would approach situations differently from before the workshop by using more nonpharmacologic interventions (40%), enhanced communication (24%), and more in-depth assessment for medical causes of delirium (19%). Thirteen percent said they would not change their approach.

Thirty-five percent of respondents had positive feelings after the simulation exercise, 40% had cared for patients in similar situations, and 35% knew delirium care should start with assessment for medical causes.

The team reviewed patient charts for documentation of confusion assessment (signs and symptoms of confusion), including the standardized CAM method and nonpharmacologic interventions. Random monthly audits, 1 month before training and 5 months after, indicated an increase in confusion assessment and documentation. For veterans with delirium, nonpharmacologic interventions increased from 9% at baseline to 53% at the 5-month audit. Hospital length of stay, however, trended toward a slight increase in number of days. These findings are consistent with those reported by Rudolph and colleagues, who also piloted multimodal education and sensory enhancement.27

Discussion

Delirium assessment and management are complex skills that require well-coordinated interdisciplinary care and significant administrative support. Clinicians are becoming increasingly aware of the mounting evidence that patients with delirium feel immediate and often long-term negative effects. Strategies that support clinicians and enhance clinical care must include multimodal education and support.

In this QI project, participants supported use of simulation education, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance delirium caregiving knowledge and skills. The majority of participants indicated that, though the simulation sessions were challenging, they also were realistic and helpful. Standardized patients provided feedback and often advised teams of needed improvement, such as spending more time in helping patients feel safe and comfortable. Coaches noted that many team members collaborated with one another but often neglected to use the pocket cue cards, family brochures, and other resources in the room. The reason is not clear. Perhaps the novelty of the resources and potential participant anxiety during the simulation were contributing factors. In future sessions, coaches must address making use of available resources.

Chart reviews indicated that nonpharmacologic management of delirium increased to 53% from < 10%. The increased use of resources in caring for patients with delirium was confirmed by the need to restock the CARES activity carts with patient diversion supplies. Given the success of this first program, another ICU education and simulation program was initiated. Findings from this QI project support using multimodal education that incorporates simulation training, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance clinical practices for care of patients with delirium.33

Methods facilitated team collaboration, patient family communication, and synthesis of much information over a relatively short period. Didactic education alone may be insufficient to adequately enhance clinical care for delirium. The impact of a multimodal strategy—including a delirium resource consultation team that provided bedside mentoring, encouraged use of pocket cue cards, and supported evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions—cannot be underestimated. In addition, simulation education also provided a unique opportunity for the health care teams to “practice” assessment, communication, and collaboration skills in a supportive setting with real-time feedback. These resources are being disseminated throughout the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC. Plans to disseminate this information to a broader national audience are under way.

Although not all facilities can access the simulation laboratory, many may be able to implement use of videos, case studies, and role-playing to enhance didactic education, to improve outcomes for patients with delirium. Enhanced clinical management of complex syndromes such as delirium may be influenced most by a combination of education, practice, and mentoring methods. Use of simulation as an adjunct teaching method is a promising strategy that may enhance care of patients with delirium. This QI project demonstrated positive educational and clinical trends in a VA setting. More studies, including randomized clinical trials, are needed in a variety of settings to further test these strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors give special thanks to Brigid Wilson, PhD, Heather O’Leary, RN, and Patrick Kilroy, SN, for their assistance in this project. The project was developed by the Cleveland VAMC interdisciplinary delirium resource team with support of a VA T-21 grant and the VISN 10 Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers.

1. ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group, Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Delirium prevention and safety: starting with the ABCDEF’s. http://www.icudelirium.org/medicalprofessionals .html. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: an under-recognized syndrome of organ dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22(2):115-126.

3. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Vitagliano G, et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41(1):70-83.

4. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522.

5. Foreman MD, Wakefield B, Culp K, Milisen K. Delirium in elderly patients: an overview of the state of the science. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(4):12-20.

6. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

7. Maldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):789-856.

8. Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451.

9. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32.

10. Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2004-2012.

11. Cohen MZ, Pace EA, Kaur G, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer leading to distress in patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Care. 2009;25(3):164-171.

12. Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):825-832.

13. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The confusion assessment method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830.

14. Neuman MD, Speck RM, Karlawish JH, Schwartz JS, Shea JA. Hospital protocols for the inpatient care of older adults: results from a statewide survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1959-1964.

15. Idemoto BK. The assessment of delirium and depression in the intensive care unit [doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University; 2005. No. 137.

16. Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Burke WJ, et al. Critical care nurses’ role in implementing the “ABCDE bundle” into practice. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(2):35-38, 40-47.

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit: executive summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(1):53-58.

18. Pun BT, Ely EW. The importance of diagnosing and managing ICU delirium. Chest. 2007;132(2):624-636.

19. Pisani MA, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Inouye SK. A research algorithm to improve detection of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):R121.

20. Voyer P, Cole MG, McCusker J, St-Jacques S, Laplante J. Accuracy of nurse documentation of delirium symptoms in medical charts. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(2):165-167.

21. Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(1):34-41.

22. Steis MR, Fick DM. Are nurses recognizing delirium? A systematic review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(9):40-48.

23. Yanamadala M, Wieland D, Heflin MT. Educational interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1983-1993.

24. Ramaswamy R, Dix EF, Drew JE, Diamond JJ, Inouye SK, Roehl BJ. Beyond grand rounds: a comprehensive and sequential intervention to improve identification of delirium. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):122-131.

25. Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178-186.

26. Inouye SK. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):393-400.

27. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-e11.

28. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. http://hartfordign.org. Accessed November 9, 2016.

29. Inouye SK. A practical program for preventing delirium in hospitalized elderly patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(11):890-896.

30. Raurell-Torredà M, Olivet-Pujol J, Romero-Collado À, Malagon-Aguilera MC, Patiño-Masó J, Baltasar-Bagué A. Case-based learning and simulation: useful tools to enhance nurses’ education? Nonrandomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(1):34-42.

31. Mast TA, Coulson LR, Meyer TC, et al. Self directed learning: wisdom from independent study programs. Res Med Educ. 1985;24:305-311.

32. Massachusetts Department of Higher Education Nursing Initiative—Simulation Scenario Library. http://www.mass.edu/nahi/Sim/Welcome.asp. Accessed November 1, 2016.

33. Vancouver Island Health Authority. Delirium in the older person: a medical emergency. Pre-Post Test. http://www.viha.ca/NR/rdonlyres/03D50FE6-AF90 -4F98-8B3B-7AE87A4B481D/0/preposttest.pdf. Reviewed August 2014. Accessed November 9, 2016.

Many clinicians continue to think that delirium or acute confusion is inevitable, untreatable, and harmless. However, nothing could be further from the truth.1 Delirium is a common and costly clinical syndrome that plagues a large percentage of older adults in a variety of settings. Numerous clinical studies conducted over the past 20 years have validated a high incidence of delirium in acute care hospitals.2-5 Reported rates of delirium among veteran and nonveteran populations vary widely, from 20% to 80%, but even these rates may reflect underrecognition and underreporting.6

Veterans with delirium pose a unique challenge to clinicians and health care systems because they often concurrently experience dementia, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and delirium. This complex syndrome caused by a myriad of environmental, physiologic, and psychological factors has been associated with profoundly poor clinical outcomes, including increased institutionalization, hospital length of stay, medication use, restraint use, falls, and mortality.3,7,8

Financial costs associated with delirium have been estimated at between $38 billion and $152 billion per year.9 In addition, this syndrome is costly in human resource expenditures, including increased burden on family members and the need for additional care providers, such as “sitters.” Families and clinicians report increased burden and stress in their interactions with these patients.10-12 Mounting evidence exists that some people with delirium never return to baseline cognitive function after even a single episode of delirium.1,8 Unfortunately, many clinicians do not recognize the seriousness of acute confusion.

Clinical practices related to routine screening for delirium vary widely. Although the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) screening tool has high sensitivity and specificity, only 17% of hospitals consistently use this tool in clinical practice.2,6,13,14 According to a survey by Ely and colleagues, physicians reported being aware of delirium but inconsistently applying treatment protocols in clinical practice.2 Nurses noted similar difficulties in consistently screening patients and using delirium management protocols.15 Given the high incidence of delirium and its associated morbidity, including long-term cognitive impairment and human and financial costs, there is an urgent need to implement programs that enhance delirium prevention, timely recognition, and effective management to improve patient outcomes and address caregiver burden.

Over the past decade, educational strategies for improving delirium prevention, recognition, and management have included didactic education, consultation, and use of protocols.2,3,5,16 Bedside mentoring, implementation of protocols, and other interventions have been proposed as well.16,17 Several program models, including consultation by psychiatrists or psychiatric advanced practice nurses, have been implemented to increase detection and treatment of delirium.2,3,5,15 These pilot programs have been successful to varying degrees but in general have not shown independent effects beyond intervention or significantly increased recognition and management of adverse consequences for most patients. The cause of these outcomes seem to be multifactorial, but the complexity of the syndrome is part of the problem.18-20

Other possible barriers to change regarding delirium-related issues in clinical practice are lack of knowledge and skills and individual attitudes.20-22 Continuing evidence exists that clinicians feel ill-prepared to help delirious patients and frustrated enough to resort to using restraints and medication as first-line treatment.17 Yanamadala and colleagues reviewed 26 studies that identified strategies for delirium education.23 Most of the studies reported on didactic teaching methods that included information on resources. Only 1 study with nursing students reported using actors for simulation training. The programs most successful in improving knowledge, skills, attitudes, practice changes, and patient outcomes seemed to be those that used multiple educational methods, including information dissemination, use of guidelines and protocols, and peer and expert feedback.

This finding is consistent with the report that didactic learning alone, though improving competency, is less likely to change behavior or improve outcomes.24 A constellation of didactic education, mentoring, use of protocols to target high-risk patients, and a therapeutic environment has helped to reduce delirium incidence.4,25,26 Rudolph and colleagues found an association between multimodal education (risk assessment, sensory improvement, sleep promotion) and shorter hospital stays and less use of restraints.27 In clinical practice,however, implementation of evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions, such as enhanced communication, mobility, nutrition, and meaningful activities, continues to lag despite education.28,29

Multimodal Education

To address these gaps in knowledge and skills, a multidisciplinary delirium resource team at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio developed a multimodal educational program incorporating simulation. The team of physicians, nurses, care coordinators, and social workers met regularly and developed interventions, educational materials, cue cards (eFigure 1), sense-enhancing aids (hearing amplifiers, puzzles, books, music CDs, prism glasses), clinical protocols, and delirium resources, such as CARES (Confusion Assessment Resource Enhancement Supplies) activity carts.

The CARES carts are small, rolling wooden carts stocked with various resources that focus on comfort and entertainment. The carts hold guided imagery CDs and Playaways (small audio players that come with ear buds for individual use and preloaded with a specific guided imagery session). The carts also hold books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthful snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player.

Bedside mentoring continued throughout this quality improvement (QI) project, and a CARES teaching tool kit was developed. This kit, which continues to be used, includes videos and webinars for professionals and family caregivers; delirium pocket cue cards for physicians, nurses, aides, and sitters; a list of patient diversion supplies; and a family brochure. Delirium resource team members continue to provide the health care team with education and support. Given the emphasis on clinicians and patient outcomes in intensive care units (ICUs), the teaching tool kit is a valuable guide for assessing and treating patients with delirium during rounds and consultations.

Simulation

Using a simulation center and standardized patients (SPs), teams of interdisciplinary care providers practiced communication techniques and recommended treatment strategies with the help of a delirium coach. Sessions were videotaped. This intervention, which used simulation training, was supported by VA grant T-21, to reduce institutionalization and promote patient-centered care.

In a clinical context, simulation involves activities that mimick the reality of the clinical environment, including physical symptoms, communication patterns, and critical decision making. Trained SPs have the unique advantage of providing interactive practice and immediate feedback in a safe, controlled setting.30

Standardized patient programs provide learners with real-life interactions for the development and practice of interpersonal communication and clinical skills. In a laboratory setting, SP programs use role-play scenarios that allow learners to practice complex assessment and communication skills. Standardized patients are effective in teaching clinical, interviewing, and communication skills to learners from a variety of disciplines, including medicine, nursing, dental, and law.31 Standardized patients also provide a safe, supportive environment conducive to learning and standardized assessment.

Standardized patients can serve as practice models and participate in sophisticated assessment and feedback of learners’ abilities and services. Interacting with SPs gives learners a chance to practice clinical and interpersonal skills with an emphasis on communication before meeting actual patients. After interacting with an SP, a learner receives feedback from a preceptor and/or the learner’s peers. The SP also may be asked to provide brief feedback—a component of the SP training process. Allowing time for feedback is an integral part of student learning.

For this QI project, the delirium team used the Mt. Sinai Skills and Simulation Center at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. The facility focuses on creative, innovative continuing learning for health care providers at all levels and is certified by the American College of Surgeons as a level 1 Comprehensive Accredited Education Institute.

After a literature review and several brainstorming sessions, the delirium team tailored case studies to veterans to simulate the intervention and train SPs for the delirium program. During training, SPs reviewed scenarios, engaged in practice sessions, and answered questions. Several SPs were familiar with the behavior of delirious patients from personal experience.

The goals of the program were to increase knowledge of delirium signs and symptoms as a medical condition that requires immediate attention; increase competency in administering CAM and in documenting its results; increase interdisciplinary communication; and increase knowledge using nonpharmacologic interventions for sensory enhancement and agitation. Enhanced interdisciplinary communication was accomplished during the simulation by assigning individuals from different disciplines to work in teams. To maximize the use of resources and limit participants’ time away from the clinical area, the administration planned and supported a daylong program that included didactic education, videos, group work sessions, and the simulation sessions with resource team members as coaches.

Methods

All participants attended an hour-long introductory didactic lecture together. Then, they were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 remaining 45-minute training sessions. Each participant attended a session that combined a video and a case study; a session of role-playing with group discussion; and 2 simulation scenario sessions. Concurrent training sessions were needed to facilitate having all 100 attendees participate within 6 hours. Attendees were multidisciplinary providers from various non-ICU medical/surgical units and outpatient geriatric clinics. They rotated among sessions to accommodate all participants.

For the simulation scenarios, 8 simulation rooms were used over 2 periods—for 16 simulation sessions total. Participants were randomly assigned to multidisciplinary groups that worked in teams to assess and recommend care and treatments for SPs who were stimulating delirium. During the simulation, delirium coaches used cue cards and verbal hints to direct teams (Simulation Exercise). After the session, participants received verbal and

Outcomes

The impact of this multimodal intervention was measured in a variety of ways—with preintervention and postintervention knowledge tests, postsimulation surveys, program surveys, and patient chart reviews. Simulation sessions had 100 attendees, including mentors (interdisciplinary resource team), champions, and nursing staff from various hospital units. Champions represented multiple disciplines and had varying levels of experience. Most of the participants were nurses (62%), followed by social workers (12%), nursing assistants (12%), psychologists (6%), and others (11%). Participants’ years of experience were < 1 year (6%), 1 to 5 years (21%), 6 to 10 years (21%), and > 10 years (52%).

Mean knowledge survey score was 84% before training and 92% after training. Recognition of delirium as a medical emergency requiring immediate follow-up was increased (P = .02), as was knowledge about delirium management, as in increasing daytime activities (P < .001) and using distraction techniques (P = .03) (Table).

More than 94% of participants said the simulation training fulfilled their education needs. More than 80% reported using the information from the delirium workshop in their practice. In reviewing the techniques presented during the workshop, participants reported that they would approach situations differently from before the workshop by using more nonpharmacologic interventions (40%), enhanced communication (24%), and more in-depth assessment for medical causes of delirium (19%). Thirteen percent said they would not change their approach.

Thirty-five percent of respondents had positive feelings after the simulation exercise, 40% had cared for patients in similar situations, and 35% knew delirium care should start with assessment for medical causes.

The team reviewed patient charts for documentation of confusion assessment (signs and symptoms of confusion), including the standardized CAM method and nonpharmacologic interventions. Random monthly audits, 1 month before training and 5 months after, indicated an increase in confusion assessment and documentation. For veterans with delirium, nonpharmacologic interventions increased from 9% at baseline to 53% at the 5-month audit. Hospital length of stay, however, trended toward a slight increase in number of days. These findings are consistent with those reported by Rudolph and colleagues, who also piloted multimodal education and sensory enhancement.27

Discussion

Delirium assessment and management are complex skills that require well-coordinated interdisciplinary care and significant administrative support. Clinicians are becoming increasingly aware of the mounting evidence that patients with delirium feel immediate and often long-term negative effects. Strategies that support clinicians and enhance clinical care must include multimodal education and support.

In this QI project, participants supported use of simulation education, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance delirium caregiving knowledge and skills. The majority of participants indicated that, though the simulation sessions were challenging, they also were realistic and helpful. Standardized patients provided feedback and often advised teams of needed improvement, such as spending more time in helping patients feel safe and comfortable. Coaches noted that many team members collaborated with one another but often neglected to use the pocket cue cards, family brochures, and other resources in the room. The reason is not clear. Perhaps the novelty of the resources and potential participant anxiety during the simulation were contributing factors. In future sessions, coaches must address making use of available resources.

Chart reviews indicated that nonpharmacologic management of delirium increased to 53% from < 10%. The increased use of resources in caring for patients with delirium was confirmed by the need to restock the CARES activity carts with patient diversion supplies. Given the success of this first program, another ICU education and simulation program was initiated. Findings from this QI project support using multimodal education that incorporates simulation training, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance clinical practices for care of patients with delirium.33

Methods facilitated team collaboration, patient family communication, and synthesis of much information over a relatively short period. Didactic education alone may be insufficient to adequately enhance clinical care for delirium. The impact of a multimodal strategy—including a delirium resource consultation team that provided bedside mentoring, encouraged use of pocket cue cards, and supported evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions—cannot be underestimated. In addition, simulation education also provided a unique opportunity for the health care teams to “practice” assessment, communication, and collaboration skills in a supportive setting with real-time feedback. These resources are being disseminated throughout the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC. Plans to disseminate this information to a broader national audience are under way.

Although not all facilities can access the simulation laboratory, many may be able to implement use of videos, case studies, and role-playing to enhance didactic education, to improve outcomes for patients with delirium. Enhanced clinical management of complex syndromes such as delirium may be influenced most by a combination of education, practice, and mentoring methods. Use of simulation as an adjunct teaching method is a promising strategy that may enhance care of patients with delirium. This QI project demonstrated positive educational and clinical trends in a VA setting. More studies, including randomized clinical trials, are needed in a variety of settings to further test these strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors give special thanks to Brigid Wilson, PhD, Heather O’Leary, RN, and Patrick Kilroy, SN, for their assistance in this project. The project was developed by the Cleveland VAMC interdisciplinary delirium resource team with support of a VA T-21 grant and the VISN 10 Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers.

Many clinicians continue to think that delirium or acute confusion is inevitable, untreatable, and harmless. However, nothing could be further from the truth.1 Delirium is a common and costly clinical syndrome that plagues a large percentage of older adults in a variety of settings. Numerous clinical studies conducted over the past 20 years have validated a high incidence of delirium in acute care hospitals.2-5 Reported rates of delirium among veteran and nonveteran populations vary widely, from 20% to 80%, but even these rates may reflect underrecognition and underreporting.6

Veterans with delirium pose a unique challenge to clinicians and health care systems because they often concurrently experience dementia, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and delirium. This complex syndrome caused by a myriad of environmental, physiologic, and psychological factors has been associated with profoundly poor clinical outcomes, including increased institutionalization, hospital length of stay, medication use, restraint use, falls, and mortality.3,7,8

Financial costs associated with delirium have been estimated at between $38 billion and $152 billion per year.9 In addition, this syndrome is costly in human resource expenditures, including increased burden on family members and the need for additional care providers, such as “sitters.” Families and clinicians report increased burden and stress in their interactions with these patients.10-12 Mounting evidence exists that some people with delirium never return to baseline cognitive function after even a single episode of delirium.1,8 Unfortunately, many clinicians do not recognize the seriousness of acute confusion.

Clinical practices related to routine screening for delirium vary widely. Although the Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) screening tool has high sensitivity and specificity, only 17% of hospitals consistently use this tool in clinical practice.2,6,13,14 According to a survey by Ely and colleagues, physicians reported being aware of delirium but inconsistently applying treatment protocols in clinical practice.2 Nurses noted similar difficulties in consistently screening patients and using delirium management protocols.15 Given the high incidence of delirium and its associated morbidity, including long-term cognitive impairment and human and financial costs, there is an urgent need to implement programs that enhance delirium prevention, timely recognition, and effective management to improve patient outcomes and address caregiver burden.

Over the past decade, educational strategies for improving delirium prevention, recognition, and management have included didactic education, consultation, and use of protocols.2,3,5,16 Bedside mentoring, implementation of protocols, and other interventions have been proposed as well.16,17 Several program models, including consultation by psychiatrists or psychiatric advanced practice nurses, have been implemented to increase detection and treatment of delirium.2,3,5,15 These pilot programs have been successful to varying degrees but in general have not shown independent effects beyond intervention or significantly increased recognition and management of adverse consequences for most patients. The cause of these outcomes seem to be multifactorial, but the complexity of the syndrome is part of the problem.18-20

Other possible barriers to change regarding delirium-related issues in clinical practice are lack of knowledge and skills and individual attitudes.20-22 Continuing evidence exists that clinicians feel ill-prepared to help delirious patients and frustrated enough to resort to using restraints and medication as first-line treatment.17 Yanamadala and colleagues reviewed 26 studies that identified strategies for delirium education.23 Most of the studies reported on didactic teaching methods that included information on resources. Only 1 study with nursing students reported using actors for simulation training. The programs most successful in improving knowledge, skills, attitudes, practice changes, and patient outcomes seemed to be those that used multiple educational methods, including information dissemination, use of guidelines and protocols, and peer and expert feedback.

This finding is consistent with the report that didactic learning alone, though improving competency, is less likely to change behavior or improve outcomes.24 A constellation of didactic education, mentoring, use of protocols to target high-risk patients, and a therapeutic environment has helped to reduce delirium incidence.4,25,26 Rudolph and colleagues found an association between multimodal education (risk assessment, sensory improvement, sleep promotion) and shorter hospital stays and less use of restraints.27 In clinical practice,however, implementation of evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions, such as enhanced communication, mobility, nutrition, and meaningful activities, continues to lag despite education.28,29

Multimodal Education

To address these gaps in knowledge and skills, a multidisciplinary delirium resource team at the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC in Ohio developed a multimodal educational program incorporating simulation. The team of physicians, nurses, care coordinators, and social workers met regularly and developed interventions, educational materials, cue cards (eFigure 1), sense-enhancing aids (hearing amplifiers, puzzles, books, music CDs, prism glasses), clinical protocols, and delirium resources, such as CARES (Confusion Assessment Resource Enhancement Supplies) activity carts.

The CARES carts are small, rolling wooden carts stocked with various resources that focus on comfort and entertainment. The carts hold guided imagery CDs and Playaways (small audio players that come with ear buds for individual use and preloaded with a specific guided imagery session). The carts also hold books, books on tape, magazines, portable CD players, music CDs, games, exercise bands, healthful snacks, DVDs, and a portable DVD player.

Bedside mentoring continued throughout this quality improvement (QI) project, and a CARES teaching tool kit was developed. This kit, which continues to be used, includes videos and webinars for professionals and family caregivers; delirium pocket cue cards for physicians, nurses, aides, and sitters; a list of patient diversion supplies; and a family brochure. Delirium resource team members continue to provide the health care team with education and support. Given the emphasis on clinicians and patient outcomes in intensive care units (ICUs), the teaching tool kit is a valuable guide for assessing and treating patients with delirium during rounds and consultations.

Simulation

Using a simulation center and standardized patients (SPs), teams of interdisciplinary care providers practiced communication techniques and recommended treatment strategies with the help of a delirium coach. Sessions were videotaped. This intervention, which used simulation training, was supported by VA grant T-21, to reduce institutionalization and promote patient-centered care.

In a clinical context, simulation involves activities that mimick the reality of the clinical environment, including physical symptoms, communication patterns, and critical decision making. Trained SPs have the unique advantage of providing interactive practice and immediate feedback in a safe, controlled setting.30

Standardized patient programs provide learners with real-life interactions for the development and practice of interpersonal communication and clinical skills. In a laboratory setting, SP programs use role-play scenarios that allow learners to practice complex assessment and communication skills. Standardized patients are effective in teaching clinical, interviewing, and communication skills to learners from a variety of disciplines, including medicine, nursing, dental, and law.31 Standardized patients also provide a safe, supportive environment conducive to learning and standardized assessment.

Standardized patients can serve as practice models and participate in sophisticated assessment and feedback of learners’ abilities and services. Interacting with SPs gives learners a chance to practice clinical and interpersonal skills with an emphasis on communication before meeting actual patients. After interacting with an SP, a learner receives feedback from a preceptor and/or the learner’s peers. The SP also may be asked to provide brief feedback—a component of the SP training process. Allowing time for feedback is an integral part of student learning.

For this QI project, the delirium team used the Mt. Sinai Skills and Simulation Center at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine. The facility focuses on creative, innovative continuing learning for health care providers at all levels and is certified by the American College of Surgeons as a level 1 Comprehensive Accredited Education Institute.

After a literature review and several brainstorming sessions, the delirium team tailored case studies to veterans to simulate the intervention and train SPs for the delirium program. During training, SPs reviewed scenarios, engaged in practice sessions, and answered questions. Several SPs were familiar with the behavior of delirious patients from personal experience.

The goals of the program were to increase knowledge of delirium signs and symptoms as a medical condition that requires immediate attention; increase competency in administering CAM and in documenting its results; increase interdisciplinary communication; and increase knowledge using nonpharmacologic interventions for sensory enhancement and agitation. Enhanced interdisciplinary communication was accomplished during the simulation by assigning individuals from different disciplines to work in teams. To maximize the use of resources and limit participants’ time away from the clinical area, the administration planned and supported a daylong program that included didactic education, videos, group work sessions, and the simulation sessions with resource team members as coaches.

Methods

All participants attended an hour-long introductory didactic lecture together. Then, they were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 remaining 45-minute training sessions. Each participant attended a session that combined a video and a case study; a session of role-playing with group discussion; and 2 simulation scenario sessions. Concurrent training sessions were needed to facilitate having all 100 attendees participate within 6 hours. Attendees were multidisciplinary providers from various non-ICU medical/surgical units and outpatient geriatric clinics. They rotated among sessions to accommodate all participants.

For the simulation scenarios, 8 simulation rooms were used over 2 periods—for 16 simulation sessions total. Participants were randomly assigned to multidisciplinary groups that worked in teams to assess and recommend care and treatments for SPs who were stimulating delirium. During the simulation, delirium coaches used cue cards and verbal hints to direct teams (Simulation Exercise). After the session, participants received verbal and

Outcomes

The impact of this multimodal intervention was measured in a variety of ways—with preintervention and postintervention knowledge tests, postsimulation surveys, program surveys, and patient chart reviews. Simulation sessions had 100 attendees, including mentors (interdisciplinary resource team), champions, and nursing staff from various hospital units. Champions represented multiple disciplines and had varying levels of experience. Most of the participants were nurses (62%), followed by social workers (12%), nursing assistants (12%), psychologists (6%), and others (11%). Participants’ years of experience were < 1 year (6%), 1 to 5 years (21%), 6 to 10 years (21%), and > 10 years (52%).

Mean knowledge survey score was 84% before training and 92% after training. Recognition of delirium as a medical emergency requiring immediate follow-up was increased (P = .02), as was knowledge about delirium management, as in increasing daytime activities (P < .001) and using distraction techniques (P = .03) (Table).

More than 94% of participants said the simulation training fulfilled their education needs. More than 80% reported using the information from the delirium workshop in their practice. In reviewing the techniques presented during the workshop, participants reported that they would approach situations differently from before the workshop by using more nonpharmacologic interventions (40%), enhanced communication (24%), and more in-depth assessment for medical causes of delirium (19%). Thirteen percent said they would not change their approach.

Thirty-five percent of respondents had positive feelings after the simulation exercise, 40% had cared for patients in similar situations, and 35% knew delirium care should start with assessment for medical causes.

The team reviewed patient charts for documentation of confusion assessment (signs and symptoms of confusion), including the standardized CAM method and nonpharmacologic interventions. Random monthly audits, 1 month before training and 5 months after, indicated an increase in confusion assessment and documentation. For veterans with delirium, nonpharmacologic interventions increased from 9% at baseline to 53% at the 5-month audit. Hospital length of stay, however, trended toward a slight increase in number of days. These findings are consistent with those reported by Rudolph and colleagues, who also piloted multimodal education and sensory enhancement.27

Discussion

Delirium assessment and management are complex skills that require well-coordinated interdisciplinary care and significant administrative support. Clinicians are becoming increasingly aware of the mounting evidence that patients with delirium feel immediate and often long-term negative effects. Strategies that support clinicians and enhance clinical care must include multimodal education and support.

In this QI project, participants supported use of simulation education, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance delirium caregiving knowledge and skills. The majority of participants indicated that, though the simulation sessions were challenging, they also were realistic and helpful. Standardized patients provided feedback and often advised teams of needed improvement, such as spending more time in helping patients feel safe and comfortable. Coaches noted that many team members collaborated with one another but often neglected to use the pocket cue cards, family brochures, and other resources in the room. The reason is not clear. Perhaps the novelty of the resources and potential participant anxiety during the simulation were contributing factors. In future sessions, coaches must address making use of available resources.

Chart reviews indicated that nonpharmacologic management of delirium increased to 53% from < 10%. The increased use of resources in caring for patients with delirium was confirmed by the need to restock the CARES activity carts with patient diversion supplies. Given the success of this first program, another ICU education and simulation program was initiated. Findings from this QI project support using multimodal education that incorporates simulation training, bedside coaching, and pocket cue cards to enhance clinical practices for care of patients with delirium.33

Methods facilitated team collaboration, patient family communication, and synthesis of much information over a relatively short period. Didactic education alone may be insufficient to adequately enhance clinical care for delirium. The impact of a multimodal strategy—including a delirium resource consultation team that provided bedside mentoring, encouraged use of pocket cue cards, and supported evidence-based nonpharmacologic interventions—cannot be underestimated. In addition, simulation education also provided a unique opportunity for the health care teams to “practice” assessment, communication, and collaboration skills in a supportive setting with real-time feedback. These resources are being disseminated throughout the Louis Stokes Cleveland VAMC. Plans to disseminate this information to a broader national audience are under way.

Although not all facilities can access the simulation laboratory, many may be able to implement use of videos, case studies, and role-playing to enhance didactic education, to improve outcomes for patients with delirium. Enhanced clinical management of complex syndromes such as delirium may be influenced most by a combination of education, practice, and mentoring methods. Use of simulation as an adjunct teaching method is a promising strategy that may enhance care of patients with delirium. This QI project demonstrated positive educational and clinical trends in a VA setting. More studies, including randomized clinical trials, are needed in a variety of settings to further test these strategies.

Acknowledgments

The authors give special thanks to Brigid Wilson, PhD, Heather O’Leary, RN, and Patrick Kilroy, SN, for their assistance in this project. The project was developed by the Cleveland VAMC interdisciplinary delirium resource team with support of a VA T-21 grant and the VISN 10 Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Centers.

1. ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group, Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Delirium prevention and safety: starting with the ABCDEF’s. http://www.icudelirium.org/medicalprofessionals .html. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: an under-recognized syndrome of organ dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22(2):115-126.

3. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Vitagliano G, et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41(1):70-83.

4. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522.

5. Foreman MD, Wakefield B, Culp K, Milisen K. Delirium in elderly patients: an overview of the state of the science. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(4):12-20.

6. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

7. Maldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):789-856.

8. Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451.

9. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32.

10. Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2004-2012.

11. Cohen MZ, Pace EA, Kaur G, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer leading to distress in patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Care. 2009;25(3):164-171.

12. Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):825-832.

13. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The confusion assessment method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830.

14. Neuman MD, Speck RM, Karlawish JH, Schwartz JS, Shea JA. Hospital protocols for the inpatient care of older adults: results from a statewide survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1959-1964.

15. Idemoto BK. The assessment of delirium and depression in the intensive care unit [doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University; 2005. No. 137.

16. Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Burke WJ, et al. Critical care nurses’ role in implementing the “ABCDE bundle” into practice. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(2):35-38, 40-47.

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit: executive summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(1):53-58.

18. Pun BT, Ely EW. The importance of diagnosing and managing ICU delirium. Chest. 2007;132(2):624-636.

19. Pisani MA, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Inouye SK. A research algorithm to improve detection of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):R121.

20. Voyer P, Cole MG, McCusker J, St-Jacques S, Laplante J. Accuracy of nurse documentation of delirium symptoms in medical charts. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(2):165-167.

21. Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(1):34-41.

22. Steis MR, Fick DM. Are nurses recognizing delirium? A systematic review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(9):40-48.

23. Yanamadala M, Wieland D, Heflin MT. Educational interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1983-1993.

24. Ramaswamy R, Dix EF, Drew JE, Diamond JJ, Inouye SK, Roehl BJ. Beyond grand rounds: a comprehensive and sequential intervention to improve identification of delirium. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):122-131.

25. Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178-186.

26. Inouye SK. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):393-400.

27. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-e11.

28. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. http://hartfordign.org. Accessed November 9, 2016.

29. Inouye SK. A practical program for preventing delirium in hospitalized elderly patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(11):890-896.

30. Raurell-Torredà M, Olivet-Pujol J, Romero-Collado À, Malagon-Aguilera MC, Patiño-Masó J, Baltasar-Bagué A. Case-based learning and simulation: useful tools to enhance nurses’ education? Nonrandomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(1):34-42.

31. Mast TA, Coulson LR, Meyer TC, et al. Self directed learning: wisdom from independent study programs. Res Med Educ. 1985;24:305-311.

32. Massachusetts Department of Higher Education Nursing Initiative—Simulation Scenario Library. http://www.mass.edu/nahi/Sim/Welcome.asp. Accessed November 1, 2016.

33. Vancouver Island Health Authority. Delirium in the older person: a medical emergency. Pre-Post Test. http://www.viha.ca/NR/rdonlyres/03D50FE6-AF90 -4F98-8B3B-7AE87A4B481D/0/preposttest.pdf. Reviewed August 2014. Accessed November 9, 2016.

1. ICU Delirium and Cognitive Impairment Study Group, Center for Health Services Research, Vanderbilt University Medical Center. Delirium prevention and safety: starting with the ABCDEF’s. http://www.icudelirium.org/medicalprofessionals .html. Accessed November 9, 2016.

2. Ely EW, Siegel MD, Inouye SK. Delirium in the intensive care unit: an under-recognized syndrome of organ dysfunction. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22(2):115-126.

3. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Vitagliano G, et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41(1):70-83.

4. Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Wright RJ, Resnick NM. Reducing delirium after hip fracture: a randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):516-522.

5. Foreman MD, Wakefield B, Culp K, Milisen K. Delirium in elderly patients: an overview of the state of the science. J Gerontol Nurs. 2001;27(4):12-20.

6. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: the confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941-948.

7. Maldonado JR. Pathoetiological model of delirium: a comprehensive understanding of the neurobiology of delirium and an evidence-based approach to prevention and treatment. Crit Care Clin. 2008;24(4):789-856.

8. Witlox J, Eurelings LS, de Jonghe JF, Kalisvaart KJ, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA. Delirium in elderly patients and the risk of postdischarge mortality, institutionalization, and dementia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2010;304(4):443-451.

9. Leslie DL, Marcantonio ER, Zhang Y, Leo-Summers L, Inouye SK. One-year health care costs associated with delirium in the elderly population. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(1):27-32.

10. Bruera E, Bush SH, Willey J, et al. Impact of delirium and recall on the level of distress in patients with advanced cancer and their family caregivers. Cancer. 2009;115(9):2004-2012.

11. Cohen MZ, Pace EA, Kaur G, Bruera E. Delirium in advanced cancer leading to distress in patients and family caregivers. J Palliat Care. 2009;25(3):164-171.

12. Patel RP, Gambrell M, Speroff T, et al. Delirium and sedation in the intensive care unit: survey of behaviors and attitudes of 1384 healthcare professionals. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(3):825-832.

13. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The confusion assessment method: a systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(5):823-830.

14. Neuman MD, Speck RM, Karlawish JH, Schwartz JS, Shea JA. Hospital protocols for the inpatient care of older adults: results from a statewide survey. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(10):1959-1964.

15. Idemoto BK. The assessment of delirium and depression in the intensive care unit [doctoral dissertation]. Cleveland, OH: Case Western Reserve University; 2005. No. 137.

16. Balas MC, Vasilevskis EE, Burke WJ, et al. Critical care nurses’ role in implementing the “ABCDE bundle” into practice. Crit Care Nurse. 2012;32(2):35-38, 40-47.

17. Barr J, Fraser GL, Puntillo K, et al; American College of Critical Care Medicine. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of pain, agitation, and delirium in adult patients in the intensive care unit: executive summary. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2013;70(1):53-58.

18. Pun BT, Ely EW. The importance of diagnosing and managing ICU delirium. Chest. 2007;132(2):624-636.

19. Pisani MA, Araujo KL, Van Ness PH, Zhang Y, Ely EW, Inouye SK. A research algorithm to improve detection of delirium in the intensive care unit. Crit Care. 2006;10(4):R121.

20. Voyer P, Cole MG, McCusker J, St-Jacques S, Laplante J. Accuracy of nurse documentation of delirium symptoms in medical charts. Int J Nurs Pract. 2008;14(2):165-167.

21. Pandharipande P, Cotton BA, Shintani A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for development of delirium in surgical and trauma intensive care unit patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(1):34-41.

22. Steis MR, Fick DM. Are nurses recognizing delirium? A systematic review. J Gerontol Nurs. 2008;34(9):40-48.

23. Yanamadala M, Wieland D, Heflin MT. Educational interventions to improve recognition of delirium: a systematic review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(11):1983-1993.

24. Ramaswamy R, Dix EF, Drew JE, Diamond JJ, Inouye SK, Roehl BJ. Beyond grand rounds: a comprehensive and sequential intervention to improve identification of delirium. Gerontologist. 2011;51(1):122-131.

25. Lundström M, Olofsson B, Stenvall M, et al. Postoperative delirium in old patients with femoral neck fracture: a randomized intervention study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19(3):178-186.

26. Inouye SK. Predisposing and precipitating factors for delirium in hospitalized older patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(5):393-400.

27. Rudolph JL, Archambault E, Kelly B; VA Boston Delirium Task Force. A delirium risk modification program is associated with hospital outcomes. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(12):957.e7-e11.

28. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing. http://hartfordign.org. Accessed November 9, 2016.

29. Inouye SK. A practical program for preventing delirium in hospitalized elderly patients. Cleve Clin J Med. 2004;71(11):890-896.

30. Raurell-Torredà M, Olivet-Pujol J, Romero-Collado À, Malagon-Aguilera MC, Patiño-Masó J, Baltasar-Bagué A. Case-based learning and simulation: useful tools to enhance nurses’ education? Nonrandomized controlled trial. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2015;47(1):34-42.

31. Mast TA, Coulson LR, Meyer TC, et al. Self directed learning: wisdom from independent study programs. Res Med Educ. 1985;24:305-311.

32. Massachusetts Department of Higher Education Nursing Initiative—Simulation Scenario Library. http://www.mass.edu/nahi/Sim/Welcome.asp. Accessed November 1, 2016.

33. Vancouver Island Health Authority. Delirium in the older person: a medical emergency. Pre-Post Test. http://www.viha.ca/NR/rdonlyres/03D50FE6-AF90 -4F98-8B3B-7AE87A4B481D/0/preposttest.pdf. Reviewed August 2014. Accessed November 9, 2016.