User login

Readmission prevention is paramount for hospitals and, by extension, hospitalist programs. Hospitalists see early and reliable outpatient follow-up as a safe landing for their most complicated patient cases. The option of a postdischarge clinic arises from the challenge to arrange adequate postdischarge care for patients who lack easy access because of insurance or provider availability. Guaranteeing postdischarge access by opening a dedicated, hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic appears to be an easy solution, but it is a solution that requires significant investment (including investment in physician and staff training and administrative support) and careful navigation of existing primary care relationships. In addition, a clinic staffed only with physicians may not be well equipped to address the complex social factors in healthcare utilization and readmission. Better understanding of the evidence supporting post discharge physician visits, several models of clinics, and the key operational questions are essential to address before crossing the inpatient-outpatient divide.

POSTDISCHARGE PHYSICIAN VISITS AND READMISSIONS

A postdischarge outpatient provider visit is often seen as a key factor in reducing readmissions. In 2013, Medicare added strength to this association by establishing transitional care management codes, which provide enhanced reimbursement to providers for a visit within 7 or 14 days of discharge, with focused attention on transitional issues.1 However, whether a postdischarge visit reduces readmissions remains unclear. Given evidence that higher primary care density is associated with lower healthcare utilization,2 CMS’s financial investment in incentivizing post discharge physician visits may be a good bet. On the other hand, simply having a primary care physician (PCP) may be a risk factor for readmission. This association suggests that postdischarge vigilance leads to identification of medical problems that lead to rehospitalization.3 This uncertainty is not resolved in systematic reviews of readmission reduction initiatives, which were not focused solely on the impact of a physician visit.4,5

The earliest study of postdischarge visits in a general medical population found an association between intensive outpatient follow-up by new providers in a Veterans Affairs population and an increase in hospital readmissions.6 This model is similar to some hospitalist models for postdischarge clinics, as the visit was with a noncontinuity provider. The largest recent study, of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, community-acquired pneumonia, or congestive heart failure (CHF) between 2009 and 2012, found increased frequency of postdischarge follow-up but no concomitant reduction in readmissions.7 Although small observational studies8 have found a postdischarge primary care visit may reduce the risk for readmission in general medical patients, the bulk of the recent data is negative.

In high-risk patients, however, there may be a clear benefit to postdischarge follow-up. In a North Carolina Medicaid population, a physician visit after discharge was associated with fewer readmissions among high-risk patients, but not among lower risk patients, whose readmission rates were low to start.9 The results of that study support the idea that risk stratification may identify patients who can benefit from more intensive outpatient follow-up. In general medical populations, existing studies may suffer from an absence of adequate risk assessment.

The evidence in specific disease states may show a clearer association between a postdischarge physician visit and reduced risk for readmission. One quarter of patients with CHF are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.10 In this disease with frequent exacerbations, a clinic visit to monitor volume status, weight, and medication adherence might reduce the frequency of readmissions or prolong the interval between rehospitalizations. A large observational study observed that earlier post discharge follow up by a cardiologist or a PCP was associated with lower risk of readmission, but only in the quintile with the closest follow-up. In addition, fewer than 40% of patients in this group had a visit within 7 days.11 In another heart failure population, follow-up with either a PCP or cardiologist within 7 days of discharge was again associated with lower risk for readmission.12 Thus, data suggest a protective effect of postdischarge visits in CHF patients, in contrast to a general medical population. Patients with end-stage renal disease may also fit in this group protected by a postdischarge physician visit, as 1 additional visit within the month after discharge was estimated to reduce rehospitalizations and produce significant cost savings.13

With other specific discharge diagnoses, results are varied. Two small observational studies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had conflicting results—one found a modest reduction in readmission and emergency department (ED) visits for patients seen by a PCP or pulmonologist within 30 days of discharge,14 and the other found no effect on readmissions but an associated reduction in mortality.15 More data are needed to clarify further the interaction of postdischarge visits with mortality, but the association between postdischarge physician visits and readmission reduction is controversial for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Finally, the evidence for dedicated postdischarge clinics is even more limited. A study of a hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic in a Veterans Affairs hospital found reduced length of stay and earlier postdischarge follow-up in a postdischarge clinic, but no effect on readmissions.16 Other studies have found earlier postdischarge follow-up with dedicated discharge clinics but have not evaluated readmission rates specifically.17In summary, the effect of postdischarge visits on risk for readmission is an area of active research, but remains unclear. The data reviewed suggest a benefit for the highest risk patients, specifically those with severe chronic illness, or those deemed high-risk with a readmission tool.9 At present, because physicians cannot accurately predict which patients will be readmitted,18 discharging physicians often take a broad approach and schedule outpatient visits for all patients. As readmission tools are further refined, the group of patients who will benefit from postdischarge care will be easier to identify, and a benefit to postdischarge visits may be seen

It is also important to note that this review emphasizes the physician visit and its potential impact on readmissions. Socioeconomic causes are increasingly being recognized as driving readmissions and other utilization.19 Whether an isolated physician visit is sufficient to prevent readmissions for patients with nonmedical drivers of healthcare utilization is unclear. For those patients, a discharge visit likely is a necessary component of a readmission reduction strategy for high-risk patients, but may be insufficient for patients who require not just an isolated visit but rather a more integrated and comprehensive care program.8,20,21

POSTDISCHARGE CLINIC MODELS

Despite the unclear relationship between postdischarge physician care and readmissions, dedicated postdischarge clinics, some staffed by hospitalists, have been adopted over the past 10 years. The three primary types of clinics arise in safety net environments, in academic medical centers, and as comprehensive high-risk patient solutions. Reviewing several types of clinics further clarifies the nature of this structural innovation.

Safety Net Hospital Models

Safety net hospitals and their hospitalists struggle with securing adequate postdischarge access for their population, which has inadequate insurance and poor access to primary care. Patient characteristics also play a role in the complex postdischarge care for this population, given its high rate of ED use (owing to perceived convenience and capabilities) for ambulatory-sensitive conditions.22 In addition, immigrants, particularly those with low English-language proficiency, underuse and have poor access to primary care.23,24 Postdischarge clinics in this environment focus first on providing a reliable postdischarge plan and then on linking to primary care. Examples of two clinics are at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington25 and Texas Health in Fort Worth.

Harborview is a 400-bed hospital affiliated with the University of Washington. More than 50% of its patients are considered indigent. The clinic was established in 2007 to provide a postdischarge option for uninsured patients, and a link to primary care in federally qualified health centers. The clinic was staffed 5 days a week with one or two hospitalists or advanced practice nurses. Visit duration was 20 minutes, 270 visits occurred per month, and the no-show rate was 30%. A small subgroup of the hospitalist group staffed the clinic. Particular clinical foci included CHF patients, patients with wound-care needs, and homeless, immigrant, and recently incarcerated patients. A key goal was connecting to longitudinal primary care, and the clinic successfully connected more than 70% of patients to primary care in community health centers. This clinic ultimately transitioned from a hospitalist practice to a primary care practice with a primary focus on post-ED follow-up for unaffiliated patients.26

In 2010, Texas Health faced a similar challenge with unaffiliated patients, and established a nurse practitioner–based clinic with hospitalist oversight to provide care primarily for patients without insurance or without an existing primary care relationship.

Academic Medical Center Models

Another clinical model is designed for patients who receive primary care at practices affiliated with academic medical centers. Although many of these patients have insurance and a PCP, there is often no availability with their continuity provider, because of the resident’s inpatient schedule or the faculty member’s conflicting priorities.27,28 Academic medical centers, including the University of California at San Francisco, the University of New Mexico, and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, have established discharge clinics within their faculty primary care practices. A model of this type of clinic was set up at Beth Israel Deaconess in 2010. Staffed by four hospitalists and using 40-minute appointments, this clinic was physically based in the primary care practice. As such, it took advantage of the existing clinic’s administrative and clinical functions, including triage, billing, and scheduling. A visit was scheduled in that clinic by the discharging physician team if a primary care appointment was not available with the patient’s continuity provider. Visits were standardized and focused on outstanding issues at discharge, medication reconciliation, and symptom trajectory. The hospitalists used the clinic’s clinical resources, including nurses, social workers, and pharmacists, but had no other dedicated staff. That there were only four hospitalists meant they were able to gain sufficient exposure to the outpatient setting, provide consistent high-quality care, and gain credibility with the PCPs. As the patients who were seen had PCPs of their own, during the visit significant attention was focused first on the postdischarge concerns, and then on promptly returning the patients to routine primary care. Significant patient outreach was used to address the clinic’s no-show rate, which was almost 50% in the early months. Within a year, the rate was down, closer to 20%. This clinic closed in 2015 after the primary care practice, in which it was based, transitioned to a patient-centered medical home. Since that time, this type of initiative has spread further, with neurohospitalist discharge clinics established, and postdischarge neurology follow-up becoming faster and more reliable.29

Academic medical centers and safety net hospitals substitute for routine primary care to address the basic challenge of primary care access, often without significant enhancements or additional resources, such as dedicated care management and pharmacy, social work, and nursing support. Commonalities of these clinics include dedicated physician staff, appointments generally longer than average outpatient appointments, and visit content concentrated on the key issues at transition (medication reconciliation, outstanding tests, symptom trajectory). As possible, clinics adopted a multidisciplinary approach, with social workers, community health workers, and nurses, to respond to the breadth of patients’ postdischarge needs, which often extend beyond pure medical need. The most frequent barriers encountered included the knowledge gap for hospitalist providers in the outpatient setting (a gap mitigated by using dedicated providers) and the patients’ high no-show rate (not surprising given that the providers are generally new to them). Few clinics have attempted to create continuity across inpatient and outpatient providers, though continuity might reduce no-shows as well as eliminate at least 1 transition.

Comprehensive High-Risk Patient Solutions

At the other end of the clinic spectrum are more integrated postdischarge approaches, which also evolved from the hospitalist model with hospitalist staffing. However, these approaches were introduced in response to the clinical needs of the highest risk patients (who are most vulnerable to frequent provider transitions), not to a systemic inability to provide routine postdischarge care.30

The most long-standing model for this type of clinic is represented by CareMore Health System, a subsidiary of Anthem.30-32 The extensivist, an expanded-scope hospitalist, acts as primary care coordinator, coordinating a multidisciplinary team for a panel of about 100 patients, representing the sickest 5% of the Medicare Advantage–insured population. Unlike the traditional hospitalist, the extensivist follows patients across all care sites, including hospital, rehabilitation sites, and outpatient clinic. For the most part, this relationship is not designed to evolve into a longitudinal relationship, but rather is an intervention only for the several-months period of acute need. Internal data have shown effects on hospital readmissions as well as length of stay.30

Another integrated clinic was established in 2013, at the University of Chicago. This was an effort to redesign care for patients at highest risk for hospitalization.33 Similar to the CareMore process, a high-risk population is identified by prior hospitalization and expected high Medicare costs. A comprehensive care physician cares for these patients across care settings. The clinic takes a team-based approach to patient care, with team members selected on the basis of patient need. Physicians have panels limited to only 200 patients, and generally spend part of the day in clinic, and part in seeing their hospitalized patients. Although reminiscent of a traditional primary care setting, this clinic is designed specifically for a high-risk, frequently hospitalized population, and therefore requires physicians with both a skill set akin to that of hospitalists, and an approach of palliative care and holistic patient care. Outcomes from this trial clinic are expected in 2017 or 2018.

LOGISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DISCHARGE CLINICS

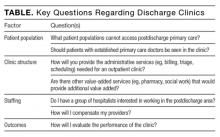

Considering some key operational questions (Table) can help guide hospitals, hospitalists, and healthcare systems as they venture into the postdischarge clinic space. Return on investment and sustainability are two key questions for postdischarge clinics.

Return on investment varies by payment structure. In capitated environments with a strong emphasis on readmissions and total medical expenditure, a successful postdischarge clinic would recoup the investment through readmission reduction. However, maintaining adequate patient volume against high no-show rates may strain the group financially. In addition, although a hospitalist group may reap few measurable benefits from this clinical exposure, the unique view of the outpatient world afforded to hospitalists working in this environment could enrich the group as a whole by providing a more well-rounded vantage point.

Another key question surrounds sustainability. The clinic at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston temporarily closed due to high inpatient volume and corresponding need for those hospitalists in the inpatient setting, early in its inception. It subsequently closed due to evolution in the clinic where it was based, rendering it unnecessary. Clinics that are contingent on other clinics will be vulnerable to external forces. Finally, staffing these clinics may be a stretch for a hospitalist group, as a partly different skill set is required for patient care in the outpatient setting. Hospitalists interested in care transitions are well suited for this role. In addition, hospitalists interested in more clinical variety, or in more schedule variety than that provided in a traditional hospitalist schedule, often enjoy the work. A vast majority of hospitalists think PCPs are responsible for postdischarge problems, and would not be interested in working in the postdischarge world.34 A poor fit for providers may lead to clinic failure.

As evident from this review, gaps in understanding the benefits of postdischarge care have persisted for 10 years. Discharge clinics have been scantly described in the literature. The primary unanswered question remains the effect on readmissions, but this has been the sole research focus to date. Other key research areas are the impact on other patient-centered clinical and system outcomes (eg, patient satisfaction, particularly for patients seeing new providers), postdischarge mortality, the effect on other adverse events, and total medical expenditure.

The healthcare system is evolving in the context of a focus on readmissions, primary care access challenges, and high-risk patients’ specific needs. These forces are spurring innovation in the realm of postdischarge physician clinics, as even the basic need for an appointment may not be met by the existing outpatient primary care system. In this context, multiple new outpatient care structures have arisen, many staffed by hospitalists. Some, such as clinics based in safety net hospitals and academic medical centers, address the simple requirement that patients who lack easy access, because of insurance status or provider availability, can see a doctor after discharge. This type of clinic may be an essential step in alleviating a strained system but may not represent a sustainable long-term solution. More comprehensive solutions for improving patient care and clinical outcomes may be offered by integrated systems, such as CareMore, which also emerged from the hospitalist model. A lasting question is whether these clinics, both the narrowly focused and the comprehensive, will have longevity in the evolving healthcare market. Inevitably, though, hospitalist directors will continue to raise such questions, and should stand to benefit from the experiences of others described in this review.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transitional Care Management Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf. Fact sheet ICN 908628.. Accessed June 29, 2016.

2. Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health care utilization and the proportion of primary care physicians. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):142-148. PubMed

3. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211-219. PubMed

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

5. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

6. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1441-1447. PubMed

7. DeLia D, Tong J, Gaboda D, Casalino LP. Post-discharge follow-up visits and hospital utilization by Medicare patients, 2007-2010. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2). PubMed

8. Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J, et al. A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1540-1546. PubMed

9. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. PubMed

10. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

11. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. PubMed

12. Lee KK, Yang J, Hernandez AF, Steimle AE, Go AS. Post-discharge follow-up characteristics associated with 30-day readmission after heart failure hospitalization. Med Care. 2016;54(4):365-372. PubMed

13. Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):2079-2087. PubMed

14. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. PubMed

15. Fidahussein SS, Croghan IT, Cha SS, Klocke DL. Posthospital follow-up visits and 30-day readmission rates in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:105-112. PubMed

16. Burke RE, Whitfield E, Prochazka AV. Effect of a hospitalist-run postdischarge clinic on outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):7-12. PubMed

17. Doctoroff L, Nijhawan A, McNally D, Vanka A, Yu R, Mukamal KJ. The characteristics and impact of a hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinic. Am J Med. 2013;126(11):1016.e9-e15. PubMed

18. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, Wachter RM, Vidyarthi AR. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):771-776. PubMed

19. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

20. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187. PubMed

21. Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999-1006. PubMed

22. Capp R, Camp-Binford M, Sobolewski S, Bulmer S, Kelley L. Do adult Medicaid enrollees prefer going to their primary care provider’s clinic rather than emergency department (ED) for low acuity conditions? Med Care. 2015;53(6):530-533. PubMed

23. Vargas Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, et al. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: the role of documentation status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):146-155. PubMed

24. Chi JT, Handcock MS. Identifying sources of health care underutilization among California’s immigrants. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1(3):207-218. PubMed

25. Martinez S. Bridging the Gap: Discharge Clinics Providing Safe Transitions for High Risk Patients. Workshop presented at: Northwest Patient Safety Conference; May 15, 2012; Seattle, WA. http://www.wapatientsafety.org/downloads/Martinez.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed April 26, 2017.

26. Elliott K, W Klein J, Basu A, Sabbatini AK. Transitional care clinics for follow-up and primary care linkage for patients discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(7):1230-1235. PubMed

27. Baxley EG, Weir S. Advanced access in academic settings: definitional challenges. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):90-91. PubMed

28. Doctoroff L, McNally D, Vanka A, Nall R, Mukamal KJ. Inpatient–outpatient transitions for patients with resident primary care physicians: access and readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):886.e15-e20. PubMed

29. Shah M, Douglas V, Scott B, Josephson SA. A neurohospitalist discharge clinic shortens the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Neurohospitalist. 2016;6(2):64-69. PubMed

30. Powers BW, Milstein A, Jain SH. Delivery models for high-risk older patients: back to the future? JAMA. 2016;315(1):23-24. PubMed

31. Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American medical home runs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1317-1326. PubMed

32. Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: the CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158-160. PubMed

33. Meltzer DO, Ruhnke GW. Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the comprehensive care physician model. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):770-777. PubMed

34. Burke RE, Ryan P. Postdischarge clinics: hospitalist attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):578-581. PubMed

Readmission prevention is paramount for hospitals and, by extension, hospitalist programs. Hospitalists see early and reliable outpatient follow-up as a safe landing for their most complicated patient cases. The option of a postdischarge clinic arises from the challenge to arrange adequate postdischarge care for patients who lack easy access because of insurance or provider availability. Guaranteeing postdischarge access by opening a dedicated, hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic appears to be an easy solution, but it is a solution that requires significant investment (including investment in physician and staff training and administrative support) and careful navigation of existing primary care relationships. In addition, a clinic staffed only with physicians may not be well equipped to address the complex social factors in healthcare utilization and readmission. Better understanding of the evidence supporting post discharge physician visits, several models of clinics, and the key operational questions are essential to address before crossing the inpatient-outpatient divide.

POSTDISCHARGE PHYSICIAN VISITS AND READMISSIONS

A postdischarge outpatient provider visit is often seen as a key factor in reducing readmissions. In 2013, Medicare added strength to this association by establishing transitional care management codes, which provide enhanced reimbursement to providers for a visit within 7 or 14 days of discharge, with focused attention on transitional issues.1 However, whether a postdischarge visit reduces readmissions remains unclear. Given evidence that higher primary care density is associated with lower healthcare utilization,2 CMS’s financial investment in incentivizing post discharge physician visits may be a good bet. On the other hand, simply having a primary care physician (PCP) may be a risk factor for readmission. This association suggests that postdischarge vigilance leads to identification of medical problems that lead to rehospitalization.3 This uncertainty is not resolved in systematic reviews of readmission reduction initiatives, which were not focused solely on the impact of a physician visit.4,5

The earliest study of postdischarge visits in a general medical population found an association between intensive outpatient follow-up by new providers in a Veterans Affairs population and an increase in hospital readmissions.6 This model is similar to some hospitalist models for postdischarge clinics, as the visit was with a noncontinuity provider. The largest recent study, of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, community-acquired pneumonia, or congestive heart failure (CHF) between 2009 and 2012, found increased frequency of postdischarge follow-up but no concomitant reduction in readmissions.7 Although small observational studies8 have found a postdischarge primary care visit may reduce the risk for readmission in general medical patients, the bulk of the recent data is negative.

In high-risk patients, however, there may be a clear benefit to postdischarge follow-up. In a North Carolina Medicaid population, a physician visit after discharge was associated with fewer readmissions among high-risk patients, but not among lower risk patients, whose readmission rates were low to start.9 The results of that study support the idea that risk stratification may identify patients who can benefit from more intensive outpatient follow-up. In general medical populations, existing studies may suffer from an absence of adequate risk assessment.

The evidence in specific disease states may show a clearer association between a postdischarge physician visit and reduced risk for readmission. One quarter of patients with CHF are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.10 In this disease with frequent exacerbations, a clinic visit to monitor volume status, weight, and medication adherence might reduce the frequency of readmissions or prolong the interval between rehospitalizations. A large observational study observed that earlier post discharge follow up by a cardiologist or a PCP was associated with lower risk of readmission, but only in the quintile with the closest follow-up. In addition, fewer than 40% of patients in this group had a visit within 7 days.11 In another heart failure population, follow-up with either a PCP or cardiologist within 7 days of discharge was again associated with lower risk for readmission.12 Thus, data suggest a protective effect of postdischarge visits in CHF patients, in contrast to a general medical population. Patients with end-stage renal disease may also fit in this group protected by a postdischarge physician visit, as 1 additional visit within the month after discharge was estimated to reduce rehospitalizations and produce significant cost savings.13

With other specific discharge diagnoses, results are varied. Two small observational studies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had conflicting results—one found a modest reduction in readmission and emergency department (ED) visits for patients seen by a PCP or pulmonologist within 30 days of discharge,14 and the other found no effect on readmissions but an associated reduction in mortality.15 More data are needed to clarify further the interaction of postdischarge visits with mortality, but the association between postdischarge physician visits and readmission reduction is controversial for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Finally, the evidence for dedicated postdischarge clinics is even more limited. A study of a hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic in a Veterans Affairs hospital found reduced length of stay and earlier postdischarge follow-up in a postdischarge clinic, but no effect on readmissions.16 Other studies have found earlier postdischarge follow-up with dedicated discharge clinics but have not evaluated readmission rates specifically.17In summary, the effect of postdischarge visits on risk for readmission is an area of active research, but remains unclear. The data reviewed suggest a benefit for the highest risk patients, specifically those with severe chronic illness, or those deemed high-risk with a readmission tool.9 At present, because physicians cannot accurately predict which patients will be readmitted,18 discharging physicians often take a broad approach and schedule outpatient visits for all patients. As readmission tools are further refined, the group of patients who will benefit from postdischarge care will be easier to identify, and a benefit to postdischarge visits may be seen

It is also important to note that this review emphasizes the physician visit and its potential impact on readmissions. Socioeconomic causes are increasingly being recognized as driving readmissions and other utilization.19 Whether an isolated physician visit is sufficient to prevent readmissions for patients with nonmedical drivers of healthcare utilization is unclear. For those patients, a discharge visit likely is a necessary component of a readmission reduction strategy for high-risk patients, but may be insufficient for patients who require not just an isolated visit but rather a more integrated and comprehensive care program.8,20,21

POSTDISCHARGE CLINIC MODELS

Despite the unclear relationship between postdischarge physician care and readmissions, dedicated postdischarge clinics, some staffed by hospitalists, have been adopted over the past 10 years. The three primary types of clinics arise in safety net environments, in academic medical centers, and as comprehensive high-risk patient solutions. Reviewing several types of clinics further clarifies the nature of this structural innovation.

Safety Net Hospital Models

Safety net hospitals and their hospitalists struggle with securing adequate postdischarge access for their population, which has inadequate insurance and poor access to primary care. Patient characteristics also play a role in the complex postdischarge care for this population, given its high rate of ED use (owing to perceived convenience and capabilities) for ambulatory-sensitive conditions.22 In addition, immigrants, particularly those with low English-language proficiency, underuse and have poor access to primary care.23,24 Postdischarge clinics in this environment focus first on providing a reliable postdischarge plan and then on linking to primary care. Examples of two clinics are at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington25 and Texas Health in Fort Worth.

Harborview is a 400-bed hospital affiliated with the University of Washington. More than 50% of its patients are considered indigent. The clinic was established in 2007 to provide a postdischarge option for uninsured patients, and a link to primary care in federally qualified health centers. The clinic was staffed 5 days a week with one or two hospitalists or advanced practice nurses. Visit duration was 20 minutes, 270 visits occurred per month, and the no-show rate was 30%. A small subgroup of the hospitalist group staffed the clinic. Particular clinical foci included CHF patients, patients with wound-care needs, and homeless, immigrant, and recently incarcerated patients. A key goal was connecting to longitudinal primary care, and the clinic successfully connected more than 70% of patients to primary care in community health centers. This clinic ultimately transitioned from a hospitalist practice to a primary care practice with a primary focus on post-ED follow-up for unaffiliated patients.26

In 2010, Texas Health faced a similar challenge with unaffiliated patients, and established a nurse practitioner–based clinic with hospitalist oversight to provide care primarily for patients without insurance or without an existing primary care relationship.

Academic Medical Center Models

Another clinical model is designed for patients who receive primary care at practices affiliated with academic medical centers. Although many of these patients have insurance and a PCP, there is often no availability with their continuity provider, because of the resident’s inpatient schedule or the faculty member’s conflicting priorities.27,28 Academic medical centers, including the University of California at San Francisco, the University of New Mexico, and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, have established discharge clinics within their faculty primary care practices. A model of this type of clinic was set up at Beth Israel Deaconess in 2010. Staffed by four hospitalists and using 40-minute appointments, this clinic was physically based in the primary care practice. As such, it took advantage of the existing clinic’s administrative and clinical functions, including triage, billing, and scheduling. A visit was scheduled in that clinic by the discharging physician team if a primary care appointment was not available with the patient’s continuity provider. Visits were standardized and focused on outstanding issues at discharge, medication reconciliation, and symptom trajectory. The hospitalists used the clinic’s clinical resources, including nurses, social workers, and pharmacists, but had no other dedicated staff. That there were only four hospitalists meant they were able to gain sufficient exposure to the outpatient setting, provide consistent high-quality care, and gain credibility with the PCPs. As the patients who were seen had PCPs of their own, during the visit significant attention was focused first on the postdischarge concerns, and then on promptly returning the patients to routine primary care. Significant patient outreach was used to address the clinic’s no-show rate, which was almost 50% in the early months. Within a year, the rate was down, closer to 20%. This clinic closed in 2015 after the primary care practice, in which it was based, transitioned to a patient-centered medical home. Since that time, this type of initiative has spread further, with neurohospitalist discharge clinics established, and postdischarge neurology follow-up becoming faster and more reliable.29

Academic medical centers and safety net hospitals substitute for routine primary care to address the basic challenge of primary care access, often without significant enhancements or additional resources, such as dedicated care management and pharmacy, social work, and nursing support. Commonalities of these clinics include dedicated physician staff, appointments generally longer than average outpatient appointments, and visit content concentrated on the key issues at transition (medication reconciliation, outstanding tests, symptom trajectory). As possible, clinics adopted a multidisciplinary approach, with social workers, community health workers, and nurses, to respond to the breadth of patients’ postdischarge needs, which often extend beyond pure medical need. The most frequent barriers encountered included the knowledge gap for hospitalist providers in the outpatient setting (a gap mitigated by using dedicated providers) and the patients’ high no-show rate (not surprising given that the providers are generally new to them). Few clinics have attempted to create continuity across inpatient and outpatient providers, though continuity might reduce no-shows as well as eliminate at least 1 transition.

Comprehensive High-Risk Patient Solutions

At the other end of the clinic spectrum are more integrated postdischarge approaches, which also evolved from the hospitalist model with hospitalist staffing. However, these approaches were introduced in response to the clinical needs of the highest risk patients (who are most vulnerable to frequent provider transitions), not to a systemic inability to provide routine postdischarge care.30

The most long-standing model for this type of clinic is represented by CareMore Health System, a subsidiary of Anthem.30-32 The extensivist, an expanded-scope hospitalist, acts as primary care coordinator, coordinating a multidisciplinary team for a panel of about 100 patients, representing the sickest 5% of the Medicare Advantage–insured population. Unlike the traditional hospitalist, the extensivist follows patients across all care sites, including hospital, rehabilitation sites, and outpatient clinic. For the most part, this relationship is not designed to evolve into a longitudinal relationship, but rather is an intervention only for the several-months period of acute need. Internal data have shown effects on hospital readmissions as well as length of stay.30

Another integrated clinic was established in 2013, at the University of Chicago. This was an effort to redesign care for patients at highest risk for hospitalization.33 Similar to the CareMore process, a high-risk population is identified by prior hospitalization and expected high Medicare costs. A comprehensive care physician cares for these patients across care settings. The clinic takes a team-based approach to patient care, with team members selected on the basis of patient need. Physicians have panels limited to only 200 patients, and generally spend part of the day in clinic, and part in seeing their hospitalized patients. Although reminiscent of a traditional primary care setting, this clinic is designed specifically for a high-risk, frequently hospitalized population, and therefore requires physicians with both a skill set akin to that of hospitalists, and an approach of palliative care and holistic patient care. Outcomes from this trial clinic are expected in 2017 or 2018.

LOGISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DISCHARGE CLINICS

Considering some key operational questions (Table) can help guide hospitals, hospitalists, and healthcare systems as they venture into the postdischarge clinic space. Return on investment and sustainability are two key questions for postdischarge clinics.

Return on investment varies by payment structure. In capitated environments with a strong emphasis on readmissions and total medical expenditure, a successful postdischarge clinic would recoup the investment through readmission reduction. However, maintaining adequate patient volume against high no-show rates may strain the group financially. In addition, although a hospitalist group may reap few measurable benefits from this clinical exposure, the unique view of the outpatient world afforded to hospitalists working in this environment could enrich the group as a whole by providing a more well-rounded vantage point.

Another key question surrounds sustainability. The clinic at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston temporarily closed due to high inpatient volume and corresponding need for those hospitalists in the inpatient setting, early in its inception. It subsequently closed due to evolution in the clinic where it was based, rendering it unnecessary. Clinics that are contingent on other clinics will be vulnerable to external forces. Finally, staffing these clinics may be a stretch for a hospitalist group, as a partly different skill set is required for patient care in the outpatient setting. Hospitalists interested in care transitions are well suited for this role. In addition, hospitalists interested in more clinical variety, or in more schedule variety than that provided in a traditional hospitalist schedule, often enjoy the work. A vast majority of hospitalists think PCPs are responsible for postdischarge problems, and would not be interested in working in the postdischarge world.34 A poor fit for providers may lead to clinic failure.

As evident from this review, gaps in understanding the benefits of postdischarge care have persisted for 10 years. Discharge clinics have been scantly described in the literature. The primary unanswered question remains the effect on readmissions, but this has been the sole research focus to date. Other key research areas are the impact on other patient-centered clinical and system outcomes (eg, patient satisfaction, particularly for patients seeing new providers), postdischarge mortality, the effect on other adverse events, and total medical expenditure.

The healthcare system is evolving in the context of a focus on readmissions, primary care access challenges, and high-risk patients’ specific needs. These forces are spurring innovation in the realm of postdischarge physician clinics, as even the basic need for an appointment may not be met by the existing outpatient primary care system. In this context, multiple new outpatient care structures have arisen, many staffed by hospitalists. Some, such as clinics based in safety net hospitals and academic medical centers, address the simple requirement that patients who lack easy access, because of insurance status or provider availability, can see a doctor after discharge. This type of clinic may be an essential step in alleviating a strained system but may not represent a sustainable long-term solution. More comprehensive solutions for improving patient care and clinical outcomes may be offered by integrated systems, such as CareMore, which also emerged from the hospitalist model. A lasting question is whether these clinics, both the narrowly focused and the comprehensive, will have longevity in the evolving healthcare market. Inevitably, though, hospitalist directors will continue to raise such questions, and should stand to benefit from the experiences of others described in this review.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Readmission prevention is paramount for hospitals and, by extension, hospitalist programs. Hospitalists see early and reliable outpatient follow-up as a safe landing for their most complicated patient cases. The option of a postdischarge clinic arises from the challenge to arrange adequate postdischarge care for patients who lack easy access because of insurance or provider availability. Guaranteeing postdischarge access by opening a dedicated, hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic appears to be an easy solution, but it is a solution that requires significant investment (including investment in physician and staff training and administrative support) and careful navigation of existing primary care relationships. In addition, a clinic staffed only with physicians may not be well equipped to address the complex social factors in healthcare utilization and readmission. Better understanding of the evidence supporting post discharge physician visits, several models of clinics, and the key operational questions are essential to address before crossing the inpatient-outpatient divide.

POSTDISCHARGE PHYSICIAN VISITS AND READMISSIONS

A postdischarge outpatient provider visit is often seen as a key factor in reducing readmissions. In 2013, Medicare added strength to this association by establishing transitional care management codes, which provide enhanced reimbursement to providers for a visit within 7 or 14 days of discharge, with focused attention on transitional issues.1 However, whether a postdischarge visit reduces readmissions remains unclear. Given evidence that higher primary care density is associated with lower healthcare utilization,2 CMS’s financial investment in incentivizing post discharge physician visits may be a good bet. On the other hand, simply having a primary care physician (PCP) may be a risk factor for readmission. This association suggests that postdischarge vigilance leads to identification of medical problems that lead to rehospitalization.3 This uncertainty is not resolved in systematic reviews of readmission reduction initiatives, which were not focused solely on the impact of a physician visit.4,5

The earliest study of postdischarge visits in a general medical population found an association between intensive outpatient follow-up by new providers in a Veterans Affairs population and an increase in hospital readmissions.6 This model is similar to some hospitalist models for postdischarge clinics, as the visit was with a noncontinuity provider. The largest recent study, of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction, community-acquired pneumonia, or congestive heart failure (CHF) between 2009 and 2012, found increased frequency of postdischarge follow-up but no concomitant reduction in readmissions.7 Although small observational studies8 have found a postdischarge primary care visit may reduce the risk for readmission in general medical patients, the bulk of the recent data is negative.

In high-risk patients, however, there may be a clear benefit to postdischarge follow-up. In a North Carolina Medicaid population, a physician visit after discharge was associated with fewer readmissions among high-risk patients, but not among lower risk patients, whose readmission rates were low to start.9 The results of that study support the idea that risk stratification may identify patients who can benefit from more intensive outpatient follow-up. In general medical populations, existing studies may suffer from an absence of adequate risk assessment.

The evidence in specific disease states may show a clearer association between a postdischarge physician visit and reduced risk for readmission. One quarter of patients with CHF are rehospitalized within 30 days of discharge.10 In this disease with frequent exacerbations, a clinic visit to monitor volume status, weight, and medication adherence might reduce the frequency of readmissions or prolong the interval between rehospitalizations. A large observational study observed that earlier post discharge follow up by a cardiologist or a PCP was associated with lower risk of readmission, but only in the quintile with the closest follow-up. In addition, fewer than 40% of patients in this group had a visit within 7 days.11 In another heart failure population, follow-up with either a PCP or cardiologist within 7 days of discharge was again associated with lower risk for readmission.12 Thus, data suggest a protective effect of postdischarge visits in CHF patients, in contrast to a general medical population. Patients with end-stage renal disease may also fit in this group protected by a postdischarge physician visit, as 1 additional visit within the month after discharge was estimated to reduce rehospitalizations and produce significant cost savings.13

With other specific discharge diagnoses, results are varied. Two small observational studies in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had conflicting results—one found a modest reduction in readmission and emergency department (ED) visits for patients seen by a PCP or pulmonologist within 30 days of discharge,14 and the other found no effect on readmissions but an associated reduction in mortality.15 More data are needed to clarify further the interaction of postdischarge visits with mortality, but the association between postdischarge physician visits and readmission reduction is controversial for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Finally, the evidence for dedicated postdischarge clinics is even more limited. A study of a hospitalist-led postdischarge clinic in a Veterans Affairs hospital found reduced length of stay and earlier postdischarge follow-up in a postdischarge clinic, but no effect on readmissions.16 Other studies have found earlier postdischarge follow-up with dedicated discharge clinics but have not evaluated readmission rates specifically.17In summary, the effect of postdischarge visits on risk for readmission is an area of active research, but remains unclear. The data reviewed suggest a benefit for the highest risk patients, specifically those with severe chronic illness, or those deemed high-risk with a readmission tool.9 At present, because physicians cannot accurately predict which patients will be readmitted,18 discharging physicians often take a broad approach and schedule outpatient visits for all patients. As readmission tools are further refined, the group of patients who will benefit from postdischarge care will be easier to identify, and a benefit to postdischarge visits may be seen

It is also important to note that this review emphasizes the physician visit and its potential impact on readmissions. Socioeconomic causes are increasingly being recognized as driving readmissions and other utilization.19 Whether an isolated physician visit is sufficient to prevent readmissions for patients with nonmedical drivers of healthcare utilization is unclear. For those patients, a discharge visit likely is a necessary component of a readmission reduction strategy for high-risk patients, but may be insufficient for patients who require not just an isolated visit but rather a more integrated and comprehensive care program.8,20,21

POSTDISCHARGE CLINIC MODELS

Despite the unclear relationship between postdischarge physician care and readmissions, dedicated postdischarge clinics, some staffed by hospitalists, have been adopted over the past 10 years. The three primary types of clinics arise in safety net environments, in academic medical centers, and as comprehensive high-risk patient solutions. Reviewing several types of clinics further clarifies the nature of this structural innovation.

Safety Net Hospital Models

Safety net hospitals and their hospitalists struggle with securing adequate postdischarge access for their population, which has inadequate insurance and poor access to primary care. Patient characteristics also play a role in the complex postdischarge care for this population, given its high rate of ED use (owing to perceived convenience and capabilities) for ambulatory-sensitive conditions.22 In addition, immigrants, particularly those with low English-language proficiency, underuse and have poor access to primary care.23,24 Postdischarge clinics in this environment focus first on providing a reliable postdischarge plan and then on linking to primary care. Examples of two clinics are at Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, Washington25 and Texas Health in Fort Worth.

Harborview is a 400-bed hospital affiliated with the University of Washington. More than 50% of its patients are considered indigent. The clinic was established in 2007 to provide a postdischarge option for uninsured patients, and a link to primary care in federally qualified health centers. The clinic was staffed 5 days a week with one or two hospitalists or advanced practice nurses. Visit duration was 20 minutes, 270 visits occurred per month, and the no-show rate was 30%. A small subgroup of the hospitalist group staffed the clinic. Particular clinical foci included CHF patients, patients with wound-care needs, and homeless, immigrant, and recently incarcerated patients. A key goal was connecting to longitudinal primary care, and the clinic successfully connected more than 70% of patients to primary care in community health centers. This clinic ultimately transitioned from a hospitalist practice to a primary care practice with a primary focus on post-ED follow-up for unaffiliated patients.26

In 2010, Texas Health faced a similar challenge with unaffiliated patients, and established a nurse practitioner–based clinic with hospitalist oversight to provide care primarily for patients without insurance or without an existing primary care relationship.

Academic Medical Center Models

Another clinical model is designed for patients who receive primary care at practices affiliated with academic medical centers. Although many of these patients have insurance and a PCP, there is often no availability with their continuity provider, because of the resident’s inpatient schedule or the faculty member’s conflicting priorities.27,28 Academic medical centers, including the University of California at San Francisco, the University of New Mexico, and the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, have established discharge clinics within their faculty primary care practices. A model of this type of clinic was set up at Beth Israel Deaconess in 2010. Staffed by four hospitalists and using 40-minute appointments, this clinic was physically based in the primary care practice. As such, it took advantage of the existing clinic’s administrative and clinical functions, including triage, billing, and scheduling. A visit was scheduled in that clinic by the discharging physician team if a primary care appointment was not available with the patient’s continuity provider. Visits were standardized and focused on outstanding issues at discharge, medication reconciliation, and symptom trajectory. The hospitalists used the clinic’s clinical resources, including nurses, social workers, and pharmacists, but had no other dedicated staff. That there were only four hospitalists meant they were able to gain sufficient exposure to the outpatient setting, provide consistent high-quality care, and gain credibility with the PCPs. As the patients who were seen had PCPs of their own, during the visit significant attention was focused first on the postdischarge concerns, and then on promptly returning the patients to routine primary care. Significant patient outreach was used to address the clinic’s no-show rate, which was almost 50% in the early months. Within a year, the rate was down, closer to 20%. This clinic closed in 2015 after the primary care practice, in which it was based, transitioned to a patient-centered medical home. Since that time, this type of initiative has spread further, with neurohospitalist discharge clinics established, and postdischarge neurology follow-up becoming faster and more reliable.29

Academic medical centers and safety net hospitals substitute for routine primary care to address the basic challenge of primary care access, often without significant enhancements or additional resources, such as dedicated care management and pharmacy, social work, and nursing support. Commonalities of these clinics include dedicated physician staff, appointments generally longer than average outpatient appointments, and visit content concentrated on the key issues at transition (medication reconciliation, outstanding tests, symptom trajectory). As possible, clinics adopted a multidisciplinary approach, with social workers, community health workers, and nurses, to respond to the breadth of patients’ postdischarge needs, which often extend beyond pure medical need. The most frequent barriers encountered included the knowledge gap for hospitalist providers in the outpatient setting (a gap mitigated by using dedicated providers) and the patients’ high no-show rate (not surprising given that the providers are generally new to them). Few clinics have attempted to create continuity across inpatient and outpatient providers, though continuity might reduce no-shows as well as eliminate at least 1 transition.

Comprehensive High-Risk Patient Solutions

At the other end of the clinic spectrum are more integrated postdischarge approaches, which also evolved from the hospitalist model with hospitalist staffing. However, these approaches were introduced in response to the clinical needs of the highest risk patients (who are most vulnerable to frequent provider transitions), not to a systemic inability to provide routine postdischarge care.30

The most long-standing model for this type of clinic is represented by CareMore Health System, a subsidiary of Anthem.30-32 The extensivist, an expanded-scope hospitalist, acts as primary care coordinator, coordinating a multidisciplinary team for a panel of about 100 patients, representing the sickest 5% of the Medicare Advantage–insured population. Unlike the traditional hospitalist, the extensivist follows patients across all care sites, including hospital, rehabilitation sites, and outpatient clinic. For the most part, this relationship is not designed to evolve into a longitudinal relationship, but rather is an intervention only for the several-months period of acute need. Internal data have shown effects on hospital readmissions as well as length of stay.30

Another integrated clinic was established in 2013, at the University of Chicago. This was an effort to redesign care for patients at highest risk for hospitalization.33 Similar to the CareMore process, a high-risk population is identified by prior hospitalization and expected high Medicare costs. A comprehensive care physician cares for these patients across care settings. The clinic takes a team-based approach to patient care, with team members selected on the basis of patient need. Physicians have panels limited to only 200 patients, and generally spend part of the day in clinic, and part in seeing their hospitalized patients. Although reminiscent of a traditional primary care setting, this clinic is designed specifically for a high-risk, frequently hospitalized population, and therefore requires physicians with both a skill set akin to that of hospitalists, and an approach of palliative care and holistic patient care. Outcomes from this trial clinic are expected in 2017 or 2018.

LOGISTICAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR DISCHARGE CLINICS

Considering some key operational questions (Table) can help guide hospitals, hospitalists, and healthcare systems as they venture into the postdischarge clinic space. Return on investment and sustainability are two key questions for postdischarge clinics.

Return on investment varies by payment structure. In capitated environments with a strong emphasis on readmissions and total medical expenditure, a successful postdischarge clinic would recoup the investment through readmission reduction. However, maintaining adequate patient volume against high no-show rates may strain the group financially. In addition, although a hospitalist group may reap few measurable benefits from this clinical exposure, the unique view of the outpatient world afforded to hospitalists working in this environment could enrich the group as a whole by providing a more well-rounded vantage point.

Another key question surrounds sustainability. The clinic at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston temporarily closed due to high inpatient volume and corresponding need for those hospitalists in the inpatient setting, early in its inception. It subsequently closed due to evolution in the clinic where it was based, rendering it unnecessary. Clinics that are contingent on other clinics will be vulnerable to external forces. Finally, staffing these clinics may be a stretch for a hospitalist group, as a partly different skill set is required for patient care in the outpatient setting. Hospitalists interested in care transitions are well suited for this role. In addition, hospitalists interested in more clinical variety, or in more schedule variety than that provided in a traditional hospitalist schedule, often enjoy the work. A vast majority of hospitalists think PCPs are responsible for postdischarge problems, and would not be interested in working in the postdischarge world.34 A poor fit for providers may lead to clinic failure.

As evident from this review, gaps in understanding the benefits of postdischarge care have persisted for 10 years. Discharge clinics have been scantly described in the literature. The primary unanswered question remains the effect on readmissions, but this has been the sole research focus to date. Other key research areas are the impact on other patient-centered clinical and system outcomes (eg, patient satisfaction, particularly for patients seeing new providers), postdischarge mortality, the effect on other adverse events, and total medical expenditure.

The healthcare system is evolving in the context of a focus on readmissions, primary care access challenges, and high-risk patients’ specific needs. These forces are spurring innovation in the realm of postdischarge physician clinics, as even the basic need for an appointment may not be met by the existing outpatient primary care system. In this context, multiple new outpatient care structures have arisen, many staffed by hospitalists. Some, such as clinics based in safety net hospitals and academic medical centers, address the simple requirement that patients who lack easy access, because of insurance status or provider availability, can see a doctor after discharge. This type of clinic may be an essential step in alleviating a strained system but may not represent a sustainable long-term solution. More comprehensive solutions for improving patient care and clinical outcomes may be offered by integrated systems, such as CareMore, which also emerged from the hospitalist model. A lasting question is whether these clinics, both the narrowly focused and the comprehensive, will have longevity in the evolving healthcare market. Inevitably, though, hospitalist directors will continue to raise such questions, and should stand to benefit from the experiences of others described in this review.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transitional Care Management Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf. Fact sheet ICN 908628.. Accessed June 29, 2016.

2. Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health care utilization and the proportion of primary care physicians. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):142-148. PubMed

3. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211-219. PubMed

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

5. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

6. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1441-1447. PubMed

7. DeLia D, Tong J, Gaboda D, Casalino LP. Post-discharge follow-up visits and hospital utilization by Medicare patients, 2007-2010. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2). PubMed

8. Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J, et al. A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1540-1546. PubMed

9. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. PubMed

10. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

11. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. PubMed

12. Lee KK, Yang J, Hernandez AF, Steimle AE, Go AS. Post-discharge follow-up characteristics associated with 30-day readmission after heart failure hospitalization. Med Care. 2016;54(4):365-372. PubMed

13. Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):2079-2087. PubMed

14. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. PubMed

15. Fidahussein SS, Croghan IT, Cha SS, Klocke DL. Posthospital follow-up visits and 30-day readmission rates in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:105-112. PubMed

16. Burke RE, Whitfield E, Prochazka AV. Effect of a hospitalist-run postdischarge clinic on outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):7-12. PubMed

17. Doctoroff L, Nijhawan A, McNally D, Vanka A, Yu R, Mukamal KJ. The characteristics and impact of a hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinic. Am J Med. 2013;126(11):1016.e9-e15. PubMed

18. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, Wachter RM, Vidyarthi AR. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):771-776. PubMed

19. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

20. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187. PubMed

21. Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999-1006. PubMed

22. Capp R, Camp-Binford M, Sobolewski S, Bulmer S, Kelley L. Do adult Medicaid enrollees prefer going to their primary care provider’s clinic rather than emergency department (ED) for low acuity conditions? Med Care. 2015;53(6):530-533. PubMed

23. Vargas Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, et al. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: the role of documentation status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):146-155. PubMed

24. Chi JT, Handcock MS. Identifying sources of health care underutilization among California’s immigrants. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1(3):207-218. PubMed

25. Martinez S. Bridging the Gap: Discharge Clinics Providing Safe Transitions for High Risk Patients. Workshop presented at: Northwest Patient Safety Conference; May 15, 2012; Seattle, WA. http://www.wapatientsafety.org/downloads/Martinez.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed April 26, 2017.

26. Elliott K, W Klein J, Basu A, Sabbatini AK. Transitional care clinics for follow-up and primary care linkage for patients discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(7):1230-1235. PubMed

27. Baxley EG, Weir S. Advanced access in academic settings: definitional challenges. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):90-91. PubMed

28. Doctoroff L, McNally D, Vanka A, Nall R, Mukamal KJ. Inpatient–outpatient transitions for patients with resident primary care physicians: access and readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):886.e15-e20. PubMed

29. Shah M, Douglas V, Scott B, Josephson SA. A neurohospitalist discharge clinic shortens the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Neurohospitalist. 2016;6(2):64-69. PubMed

30. Powers BW, Milstein A, Jain SH. Delivery models for high-risk older patients: back to the future? JAMA. 2016;315(1):23-24. PubMed

31. Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American medical home runs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1317-1326. PubMed

32. Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: the CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158-160. PubMed

33. Meltzer DO, Ruhnke GW. Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the comprehensive care physician model. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):770-777. PubMed

34. Burke RE, Ryan P. Postdischarge clinics: hospitalist attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):578-581. PubMed

1. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Transitional Care Management Services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/Transitional-Care-Management-Services-Fact-Sheet-ICN908628.pdf. Fact sheet ICN 908628.. Accessed June 29, 2016.

2. Kravet SJ, Shore AD, Miller R, Green GB, Kolodner K, Wright SM. Health care utilization and the proportion of primary care physicians. Am J Med. 2008;121(2):142-148. PubMed

3. Hasan O, Meltzer DO, Shaykevich SA, et al. Hospital readmission in general medicine patients: a prediction model. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(3):211-219. PubMed

4. Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520-528. PubMed

5. Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095-1107. PubMed

6. Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG. Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(22):1441-1447. PubMed

7. DeLia D, Tong J, Gaboda D, Casalino LP. Post-discharge follow-up visits and hospital utilization by Medicare patients, 2007-2010. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2014;4(2). PubMed

8. Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J, et al. A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1540-1546. PubMed

9. Jackson C, Shahsahebi M, Wedlake T, DuBard CA. Timeliness of outpatient follow-up: an evidence-based approach for planning after hospital discharge. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):115-122. PubMed

10. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

11. Hernandez AF, Greiner MA, Fonarow GC, et al. Relationship between early physician follow-up and 30-day readmission among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized for heart failure. JAMA. 2010;303(17):1716-1722. PubMed

12. Lee KK, Yang J, Hernandez AF, Steimle AE, Go AS. Post-discharge follow-up characteristics associated with 30-day readmission after heart failure hospitalization. Med Care. 2016;54(4):365-372. PubMed

13. Erickson KF, Winkelmayer WC, Chertow GM, Bhattacharya J. Physician visits and 30-day hospital readmissions in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(9):2079-2087. PubMed

14. Sharma G, Kuo YF, Freeman JL, Zhang DD, Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. PubMed

15. Fidahussein SS, Croghan IT, Cha SS, Klocke DL. Posthospital follow-up visits and 30-day readmission rates in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:105-112. PubMed

16. Burke RE, Whitfield E, Prochazka AV. Effect of a hospitalist-run postdischarge clinic on outcomes. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(1):7-12. PubMed

17. Doctoroff L, Nijhawan A, McNally D, Vanka A, Yu R, Mukamal KJ. The characteristics and impact of a hospitalist-staffed post-discharge clinic. Am J Med. 2013;126(11):1016.e9-e15. PubMed

18. Allaudeen N, Schnipper JL, Orav EJ, Wachter RM, Vidyarthi AR. Inability of providers to predict unplanned readmissions. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(7):771-776. PubMed

19. Barnett ML, Hsu J, McWilliams J. Patient characteristics and differences in hospital readmission rates. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(11):1803-1812. PubMed

20. Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187. PubMed

21. Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M. Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999-1006. PubMed

22. Capp R, Camp-Binford M, Sobolewski S, Bulmer S, Kelley L. Do adult Medicaid enrollees prefer going to their primary care provider’s clinic rather than emergency department (ED) for low acuity conditions? Med Care. 2015;53(6):530-533. PubMed

23. Vargas Bustamante A, Fang H, Garza J, et al. Variations in healthcare access and utilization among Mexican immigrants: the role of documentation status. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(1):146-155. PubMed

24. Chi JT, Handcock MS. Identifying sources of health care underutilization among California’s immigrants. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2014;1(3):207-218. PubMed

25. Martinez S. Bridging the Gap: Discharge Clinics Providing Safe Transitions for High Risk Patients. Workshop presented at: Northwest Patient Safety Conference; May 15, 2012; Seattle, WA. http://www.wapatientsafety.org/downloads/Martinez.pdf. Published 2011. Accessed April 26, 2017.

26. Elliott K, W Klein J, Basu A, Sabbatini AK. Transitional care clinics for follow-up and primary care linkage for patients discharged from the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(7):1230-1235. PubMed

27. Baxley EG, Weir S. Advanced access in academic settings: definitional challenges. Ann Fam Med. 2009;7(1):90-91. PubMed

28. Doctoroff L, McNally D, Vanka A, Nall R, Mukamal KJ. Inpatient–outpatient transitions for patients with resident primary care physicians: access and readmission. Am J Med. 2014;127(9):886.e15-e20. PubMed

29. Shah M, Douglas V, Scott B, Josephson SA. A neurohospitalist discharge clinic shortens the transition from inpatient to outpatient care. Neurohospitalist. 2016;6(2):64-69. PubMed

30. Powers BW, Milstein A, Jain SH. Delivery models for high-risk older patients: back to the future? JAMA. 2016;315(1):23-24. PubMed

31. Milstein A, Gilbertson E. American medical home runs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009;28(5):1317-1326. PubMed

32. Reuben DB. Physicians in supporting roles in chronic disease care: the CareMore model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(1):158-160. PubMed

33. Meltzer DO, Ruhnke GW. Redesigning care for patients at increased hospitalization risk: the comprehensive care physician model. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(5):770-777. PubMed

34. Burke RE, Ryan P. Postdischarge clinics: hospitalist attitudes and experiences. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(10):578-581. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine