User login

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1 Rapid growth=cancer?

Mrs. G., 47 years old, has had uterine fibroids the size of a 12-week pregnancy for about 6 years. At today’s examination, however, her uterus feels about the size of a 16-week pregnancy.

She is aware that her abdomen is bigger, and she complains of some abdominal pressure and urinary frequency. She reports no abnormal bleeding and no abdominal pain.

Mrs. G. is upset because another physician told her she might have cancer and needs a hysterectomy immediately. She tells you that she does not want a hysterectomy unless “it’s absolutely necessary.”

Ultrasonography at this visit reveals that two of the three fibroids noted on a previous sonogram have grown—one from 6 cm to 9 cm in diameter; the other from 5 cm to 8 cm.

What do you tell Mrs. G.?

Understanding myomas

Uterine fibroids, also called myomas, are benign, monoclonal tumors of the myometrium that contain collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycan. The collagen fibrils are abnormally formed and in disarray; they look like the collagen found in keloids.1 Although the precise causes of fibroids are unknown, hormonal, genetic, and growth factors appear to be involved in their development and growth.2,3

About 40% of fibroids are chromosomally abnormal; the remaining 60% may have undetected mutations. More than 100 genes have been found to be up-regulated or down-regulated in fibroid cells. Many of these genes appear to regulate cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and mitogenesis.

- A myoma is benign tumor of the myometrium

- In a premenopausal woman, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates the presence of uterine sarcoma

- In an older woman who experiences uterine growth, abdominal pain, and irregular vaginal bleeding, pelvic malignancy may be suspected; an increased level of LDH isoenzyme 3 with increased gadolinium uptake on MRI within 40 to 60 seconds suggests a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma

- Most fibroids have no impact on fertility, but submucosal fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removing them increases fertility

- Location, size, number, and extent of myoma penetration into the myometrium can be evaluated by pelvic MRI, with coronal, axial, and sagittal images without gadolinium contrast

- Given the risks associated with surgery and the lack of proof of efficacy, myomectomy to improve fertility should be undertaken with caution

- Most myomas do not grow during pregnancy. Unfavorable pregnancy outcomes are very rare in women with myomas.

- Oral contraceptives and postmenopausal hormone therapy almost never influence fibroid growth. Women with fibroids can usually use these therapies safely.

Differentiating benign myoma from uterine sarcoma

Myomas have chromosomal rearrangements similar to other benign lesions, whereas leiomyosarcomas are undifferentiated and have complex chromosomal rearrangements not seen in myomas.4 Genetic differences between myomas and leiomyosarcomas indicate they most likely have distinct origins, and that leiomyosarcomas do not result from malignant degeneration of myomas.2

In premenopausal women, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates uterine sarcoma: One study found only one sarcoma among 371 (0.26%) women operated on for rapid growth of a presumed myoma, and no sarcomas were found in the 198 women who had a 6-week-pregnancy-equivalent increase in uterine size over 1 year.5

Clinical indications. The clinical signs that would lead to suspicion of pelvic malignancy are:

- older age

- abdominal pain

- irregular vaginal bleeding.6

The average age of 2,098 women with uterine sarcoma reported in the SEER (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) cancer database from 1989 to 1999 was 63 years, whereas a review of the literature found a mean age of 36 years in women subjected to myomectomy who did not have sarcoma.3,7

Diagnostic tests. The distinction between benign myoma and leiomyosarcoma need not be based on clinical signs alone. Preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma may be possible, using laboratory values of total serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and LDH isoenzyme 3 plus gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Gd-DTPA), with initial images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. A study of 87 women with fibroids, 10 women with leiomyosarcoma, and 130 women with degenerating fibroids reported 100% specificity, 100% positive predictive value, 100% negative predictive value, and 100% diagnostic accuracy for leiomyosarcoma with this combination diagnostic procedure.8

CASE 1 RESOLVED What advice for Mrs. G.?

You order a gadolinium-enhanced, dynamic MRI scan and have blood drawn for total LDH and LDH isoenzymes. Total LDH and isoenzyme 3 are normal. MRI shows no increased enhancement of the fibroids on images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. You advise the patient that there is no evidence of cancer (sarcoma) and no urgent need for hysterectomy. You also tell her that, because she is symptomatic, myomectomy is an option that will preserve her uterus.

CASE 2 Fibroids, and contemplating childbearing

Mrs. H., a 35-year-old nulligravida, comes to the office for her first visit with you. She has no complaints, but your pelvic examination reveals a 10 week-size enlarged uterus. A sonogram shows a 6-cm subserosal fibroid and a 3-cm intramural fibroid near the endometrial cavity (see FIGURE). This patient was recently married and wants to become pregnant within the coming year.

When you tell Mrs. H. that she has fibroids, she grows concerned. She asks: “Will this affect my fertility, or a pregnancy?” and “Do I need surgery?”

You explain that the larger, subserosal fibroid is not a concern. The smaller, intramural fibroid could, however, have an impact on fertility and pregnancy if it distorts the uterine cavity.

To find out if that is the case, you order a saline infusion sonogram, which demonstrates, clearly, a normal cavity without distortion by the fibroid.

What is your advice to this woman?

Submucous fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removal increases fertility. Otherwise, neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids appear to affect the fertility rate; removal has not been shown to increase fertility. Meta-analysis of 11 studies found that submucous myomas that distort the uterine cavity appear to decrease the pregnancy rate by 70% (relative risk [RR], 0.32; confidence interval [CI], 0.13–0.70).9

Assessing the uterine cavity. Evaluating a woman with fibroids for fertility requires reliable assessment of the uterine cavity. Hysteroscopy and saline infusion sonography have been shown to be far superior to transvaginal sonography or hysterosalpingography for detecting submucosal fibroids.10

The best modality for determining the extent of submucosal penetration of a myoma into the myometrium is MRI. It is also an excellent modality for evaluating the size, position, and number of multiple fibroids.11 The drawback to using MRI? It is more costly than other modalities.

Note: Classification of submucosal fibroids is based on the fraction of the mass within the cavity:

- Class 0 myomas are entirely intracavitary

- Class I myomas have 50% or more of the fibroid within the cavity

- Class II myomas have less than 50% within the cavity.12

Resection and fertility. Submucous fibroids can often be removed hysteroscopically. Systematic review of the evidence found that resection-restored fertility is equal to that of infertile controls undergoing in vitro fertilization who do not have fibroids (RR, 1.72; CI, 1.13–2.58).9 In that review, the presence of neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids decreased fertility (intramural: RR, 0.94, and CI, 0.73–1.20; subserosal: RR, 1.1, and CI, 0.06–1.72). Furthermore, removal of intramural and subserosal myomas by abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy did not improve fertility. An updated unpublished meta-analysis, including studies published after 2001, came to the same conclusion (Pritts E, personal communication, 2008).

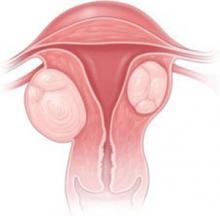

CASE 2: Subserosal, intramural myomas cause concern

In a woman contemplating childbearing, does a subserosal (left) or intramural (right) myoma present a problem because of potential to distort the uterine cavity?

Fibroids and pregnancy

The incidence of sonographically detected fibroids during pregnancy is low.13 Among 12,600 women at a prenatal clinic, routine second-trimester sonography identified myomas in 183 (mean age, 33 years)—an incidence of 1.5%.

Pregnancy has a variable and unpredictable effect on myoma growth, likely dependent on individual differences in genetics, circulating growth factors, and myoma-localized receptors. Most myomas do not, however, grow during pregnancy. A prospective study of pregnant women who had a single myoma found that 69% had no increase in volume throughout their pregnancy. In women who were noted to have an increase in the volume of their myoma, the greatest growth occurred before 10 weeks’ gestation. No relationship was found between initial myoma volume and myoma growth during the gestational period. 14

Do myomas complicate pregnancy?

Very rarely. Two studies reported on outcomes in large populations of pregnant women who were examined with routine second-trimester ultrasonography, with follow-up and delivery at the same institution.

In one of those studies, 12,600 pregnant women were evaluated, and the outcome in 167 women who were given a diagnosis of myoma was compared with the outcome in women who did not have a myoma.15 Despite similar clinical management between the two groups, no significant differences were seen in regard to the incidence of:

- preterm delivery

- premature rupture of membranes

- fetal growth restriction

- placenta previa

- placental abruption

- postpartum hemorrhage

- retained placenta.

Only cesarean section was more common among women with fibroids (23% vs 12%).

The second study reviewed 15,104 pregnancies and compared 401 women found to have myomas and the remaining women who did not.16 Although the presence of myoma did not increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes, operative vaginal delivery, chorioamnionitis, or endomyometritis, there was some increased risk of pre-term delivery (19.2% vs 12.7%), placenta previa (3.5% vs 1.8%), and post-partum hemorrhage (8.3% vs 2.9%). Cesarean section was, again, more common (49.1% vs 21.4%).

Do myomas injure the fetus?

Fetal injury as a consequence of fibroids has been reported very infrequently. A review of the literature from 1980 to 2005 revealed only four cases—one each of:

- fetal head anomalies with fetal growth restriction

- postural deformity

- limb reduction

- fetal head deformation with torticollis.17-19

CASE 2 RESOLVED Should Mrs. H. have a myomectomy?

Probably not. Abdominal and laparoscopic myomectomy involve substantial operative and anesthetic risks, including infection, postoperative adhesions, a very small risk of uterine rupture during pregnancy, and increased likelihood of cesarean section. Costs are also substantial, involving not only the expense of surgery, but also patient discomfort and time for recovery. Therefore, until it is proved that intramural myomas decrease fertility and myomectomy increases fertility, surgery should be undertaken with caution. As far as the effects of myoma on pregnancy are concerned, no data are available by which to compare pregnancy outcomes following myomectomy with pregnancy outcomes in women whose myomas are untreated. Randomized studies are needed to clarify these important issues.

CASES 3 & 4 The effects of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy

Mrs. J. is a 32-year-old G0P0 woman who has a 5-cm fundal myoma. She is sexually active and wants to use an oral contraceptive (OC). She has heard from friends, however, that taking an OC makes fibroids grow, and she asks for your advice.

The same day, you see Mrs. K., a 54-year-old, recently menopausal woman. She complains of severe hot flashes and night sweats that disturb her sleep. She has had asymptomatic uterine fibroids for about 10 years and, although she would like to take menopausal hormone therapy, she is worried that the medication will make the fibroids larger.

How do you advise these two women?

OCs. OCs do not appear to influence the growth of fibroids. One study found a slightly increased risk of fibroids, another study found no increased risk, and a third found a decreased risk.18,19 These studies are retrospective, however, and may be marked by selection bias.

Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. Postmenopausal hormone therapy does not ordinarily cause fibroid growth. After 3 years, only three of 34 (8%) post-menopausal women who had fibroids and were treated with 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and 5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) a day had any increase in the size of fibroids.20 If any increase in the size of the uterus is noted, it is likely related to progestins.

A study found that 23% of women taking oral estrogen plus 2.5 mg of MPA a day for 1 year had a slight increase in the size of fibroids, whereas 50% of women taking 5 mg of MPA had an increase in size (mean increase in diameter, 3.2 cm).21 Transdermal estrogen plus oral MPA was shown, after 1 year, to cause, on average, a 0.5-cm increase in the diameter of fibroids; oral estrogen and MPA caused no increase in size.22

CASES RESOLVED Rx: Reassurance

Advise Mrs. J. that taking an OC is unlikely to make her fibroids grow larger.

Mrs. K., who is older, can seek relief from postmenopausal symptoms by taking hormone therapy without fear of her fibroids being stimulated to grow.

1. Stewart EA, Friedman AJ, Peck K, Nowak RA. Relative overexpression of collagen type I and collagen type III messenger ribonucleic acids by uterine leiomyomas during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:900-906.

2. Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1037-1054.

3. Parker W. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:725-736.

4. Quade BJ, Wang TY, Sornberger K, Dal Cin P, Mutter GL, Morton CC. Molecular pathogenesis of uterine smooth muscle tumors from transcriptional profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40:97-108.

5. Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:414-418.

6. Boutselis JG, Ullery JC. Sarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1962;20:23-35.

7. Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989-1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:204-208.

8. Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K, Maruo T. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:354-361.

9. Pritts EA. Fibroids and infertility: a systematic review of the evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:483-491.

10. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:350-357.

11. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Olesen F. Imaging techniques for evaluation of the uterine cavity and endometrium in premenopausal patients before minimally invasive surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:388-403.

12. Cohen LS, Valle RF. Role of vaginal sonography and hysterosonography in the endoscopic treatment of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:197-204.

13. Cooper NP, Okolo S. Fibroids in pregnancy—common but poorly understood. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:132-138.

14. Rosati P, Exacoustos C, Mancuso S. Longitudinal evaluation of uterine myoma growth during pregnancy. A sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:511-515.

15. Vergani P, Ghidini A, Strobelt N, et al. Do uterine leiomyomas influence pregnancy outcome? Am J Perinatol. 1994;11:356-358.

16. Qidwai GI, Caughey AB, Jacoby AF. Obstetric outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:376-382.

17. Joo JG, Inovay J, Silhavy M, Papp Z. Successful enucleation of a necrotizing fibroid causing oligohydramnios and fetal postural deformity in the 25th week of gestation. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:923-925.

18. Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:359-362.

19. Ratner H. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:1027.-

20. Yang CH, Lee JN, Hsu SC, Kuo CH, Tsai EM. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women—a 3-year study. Maturitas. 2002;43:35-39.

21. Palomba S, Sena T, Morelli M, Noia R, Zullo F, Mastrantonio P. Effect of different doses of progestin on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:199-201.

22. Sener AB, Seçkin NC, Ozmen S, Gökmen O, Dogu N, Ekici E. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:354-357.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1 Rapid growth=cancer?

Mrs. G., 47 years old, has had uterine fibroids the size of a 12-week pregnancy for about 6 years. At today’s examination, however, her uterus feels about the size of a 16-week pregnancy.

She is aware that her abdomen is bigger, and she complains of some abdominal pressure and urinary frequency. She reports no abnormal bleeding and no abdominal pain.

Mrs. G. is upset because another physician told her she might have cancer and needs a hysterectomy immediately. She tells you that she does not want a hysterectomy unless “it’s absolutely necessary.”

Ultrasonography at this visit reveals that two of the three fibroids noted on a previous sonogram have grown—one from 6 cm to 9 cm in diameter; the other from 5 cm to 8 cm.

What do you tell Mrs. G.?

Understanding myomas

Uterine fibroids, also called myomas, are benign, monoclonal tumors of the myometrium that contain collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycan. The collagen fibrils are abnormally formed and in disarray; they look like the collagen found in keloids.1 Although the precise causes of fibroids are unknown, hormonal, genetic, and growth factors appear to be involved in their development and growth.2,3

About 40% of fibroids are chromosomally abnormal; the remaining 60% may have undetected mutations. More than 100 genes have been found to be up-regulated or down-regulated in fibroid cells. Many of these genes appear to regulate cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and mitogenesis.

- A myoma is benign tumor of the myometrium

- In a premenopausal woman, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates the presence of uterine sarcoma

- In an older woman who experiences uterine growth, abdominal pain, and irregular vaginal bleeding, pelvic malignancy may be suspected; an increased level of LDH isoenzyme 3 with increased gadolinium uptake on MRI within 40 to 60 seconds suggests a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma

- Most fibroids have no impact on fertility, but submucosal fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removing them increases fertility

- Location, size, number, and extent of myoma penetration into the myometrium can be evaluated by pelvic MRI, with coronal, axial, and sagittal images without gadolinium contrast

- Given the risks associated with surgery and the lack of proof of efficacy, myomectomy to improve fertility should be undertaken with caution

- Most myomas do not grow during pregnancy. Unfavorable pregnancy outcomes are very rare in women with myomas.

- Oral contraceptives and postmenopausal hormone therapy almost never influence fibroid growth. Women with fibroids can usually use these therapies safely.

Differentiating benign myoma from uterine sarcoma

Myomas have chromosomal rearrangements similar to other benign lesions, whereas leiomyosarcomas are undifferentiated and have complex chromosomal rearrangements not seen in myomas.4 Genetic differences between myomas and leiomyosarcomas indicate they most likely have distinct origins, and that leiomyosarcomas do not result from malignant degeneration of myomas.2

In premenopausal women, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates uterine sarcoma: One study found only one sarcoma among 371 (0.26%) women operated on for rapid growth of a presumed myoma, and no sarcomas were found in the 198 women who had a 6-week-pregnancy-equivalent increase in uterine size over 1 year.5

Clinical indications. The clinical signs that would lead to suspicion of pelvic malignancy are:

- older age

- abdominal pain

- irregular vaginal bleeding.6

The average age of 2,098 women with uterine sarcoma reported in the SEER (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) cancer database from 1989 to 1999 was 63 years, whereas a review of the literature found a mean age of 36 years in women subjected to myomectomy who did not have sarcoma.3,7

Diagnostic tests. The distinction between benign myoma and leiomyosarcoma need not be based on clinical signs alone. Preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma may be possible, using laboratory values of total serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and LDH isoenzyme 3 plus gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Gd-DTPA), with initial images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. A study of 87 women with fibroids, 10 women with leiomyosarcoma, and 130 women with degenerating fibroids reported 100% specificity, 100% positive predictive value, 100% negative predictive value, and 100% diagnostic accuracy for leiomyosarcoma with this combination diagnostic procedure.8

CASE 1 RESOLVED What advice for Mrs. G.?

You order a gadolinium-enhanced, dynamic MRI scan and have blood drawn for total LDH and LDH isoenzymes. Total LDH and isoenzyme 3 are normal. MRI shows no increased enhancement of the fibroids on images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. You advise the patient that there is no evidence of cancer (sarcoma) and no urgent need for hysterectomy. You also tell her that, because she is symptomatic, myomectomy is an option that will preserve her uterus.

CASE 2 Fibroids, and contemplating childbearing

Mrs. H., a 35-year-old nulligravida, comes to the office for her first visit with you. She has no complaints, but your pelvic examination reveals a 10 week-size enlarged uterus. A sonogram shows a 6-cm subserosal fibroid and a 3-cm intramural fibroid near the endometrial cavity (see FIGURE). This patient was recently married and wants to become pregnant within the coming year.

When you tell Mrs. H. that she has fibroids, she grows concerned. She asks: “Will this affect my fertility, or a pregnancy?” and “Do I need surgery?”

You explain that the larger, subserosal fibroid is not a concern. The smaller, intramural fibroid could, however, have an impact on fertility and pregnancy if it distorts the uterine cavity.

To find out if that is the case, you order a saline infusion sonogram, which demonstrates, clearly, a normal cavity without distortion by the fibroid.

What is your advice to this woman?

Submucous fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removal increases fertility. Otherwise, neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids appear to affect the fertility rate; removal has not been shown to increase fertility. Meta-analysis of 11 studies found that submucous myomas that distort the uterine cavity appear to decrease the pregnancy rate by 70% (relative risk [RR], 0.32; confidence interval [CI], 0.13–0.70).9

Assessing the uterine cavity. Evaluating a woman with fibroids for fertility requires reliable assessment of the uterine cavity. Hysteroscopy and saline infusion sonography have been shown to be far superior to transvaginal sonography or hysterosalpingography for detecting submucosal fibroids.10

The best modality for determining the extent of submucosal penetration of a myoma into the myometrium is MRI. It is also an excellent modality for evaluating the size, position, and number of multiple fibroids.11 The drawback to using MRI? It is more costly than other modalities.

Note: Classification of submucosal fibroids is based on the fraction of the mass within the cavity:

- Class 0 myomas are entirely intracavitary

- Class I myomas have 50% or more of the fibroid within the cavity

- Class II myomas have less than 50% within the cavity.12

Resection and fertility. Submucous fibroids can often be removed hysteroscopically. Systematic review of the evidence found that resection-restored fertility is equal to that of infertile controls undergoing in vitro fertilization who do not have fibroids (RR, 1.72; CI, 1.13–2.58).9 In that review, the presence of neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids decreased fertility (intramural: RR, 0.94, and CI, 0.73–1.20; subserosal: RR, 1.1, and CI, 0.06–1.72). Furthermore, removal of intramural and subserosal myomas by abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy did not improve fertility. An updated unpublished meta-analysis, including studies published after 2001, came to the same conclusion (Pritts E, personal communication, 2008).

CASE 2: Subserosal, intramural myomas cause concern

In a woman contemplating childbearing, does a subserosal (left) or intramural (right) myoma present a problem because of potential to distort the uterine cavity?

Fibroids and pregnancy

The incidence of sonographically detected fibroids during pregnancy is low.13 Among 12,600 women at a prenatal clinic, routine second-trimester sonography identified myomas in 183 (mean age, 33 years)—an incidence of 1.5%.

Pregnancy has a variable and unpredictable effect on myoma growth, likely dependent on individual differences in genetics, circulating growth factors, and myoma-localized receptors. Most myomas do not, however, grow during pregnancy. A prospective study of pregnant women who had a single myoma found that 69% had no increase in volume throughout their pregnancy. In women who were noted to have an increase in the volume of their myoma, the greatest growth occurred before 10 weeks’ gestation. No relationship was found between initial myoma volume and myoma growth during the gestational period. 14

Do myomas complicate pregnancy?

Very rarely. Two studies reported on outcomes in large populations of pregnant women who were examined with routine second-trimester ultrasonography, with follow-up and delivery at the same institution.

In one of those studies, 12,600 pregnant women were evaluated, and the outcome in 167 women who were given a diagnosis of myoma was compared with the outcome in women who did not have a myoma.15 Despite similar clinical management between the two groups, no significant differences were seen in regard to the incidence of:

- preterm delivery

- premature rupture of membranes

- fetal growth restriction

- placenta previa

- placental abruption

- postpartum hemorrhage

- retained placenta.

Only cesarean section was more common among women with fibroids (23% vs 12%).

The second study reviewed 15,104 pregnancies and compared 401 women found to have myomas and the remaining women who did not.16 Although the presence of myoma did not increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes, operative vaginal delivery, chorioamnionitis, or endomyometritis, there was some increased risk of pre-term delivery (19.2% vs 12.7%), placenta previa (3.5% vs 1.8%), and post-partum hemorrhage (8.3% vs 2.9%). Cesarean section was, again, more common (49.1% vs 21.4%).

Do myomas injure the fetus?

Fetal injury as a consequence of fibroids has been reported very infrequently. A review of the literature from 1980 to 2005 revealed only four cases—one each of:

- fetal head anomalies with fetal growth restriction

- postural deformity

- limb reduction

- fetal head deformation with torticollis.17-19

CASE 2 RESOLVED Should Mrs. H. have a myomectomy?

Probably not. Abdominal and laparoscopic myomectomy involve substantial operative and anesthetic risks, including infection, postoperative adhesions, a very small risk of uterine rupture during pregnancy, and increased likelihood of cesarean section. Costs are also substantial, involving not only the expense of surgery, but also patient discomfort and time for recovery. Therefore, until it is proved that intramural myomas decrease fertility and myomectomy increases fertility, surgery should be undertaken with caution. As far as the effects of myoma on pregnancy are concerned, no data are available by which to compare pregnancy outcomes following myomectomy with pregnancy outcomes in women whose myomas are untreated. Randomized studies are needed to clarify these important issues.

CASES 3 & 4 The effects of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy

Mrs. J. is a 32-year-old G0P0 woman who has a 5-cm fundal myoma. She is sexually active and wants to use an oral contraceptive (OC). She has heard from friends, however, that taking an OC makes fibroids grow, and she asks for your advice.

The same day, you see Mrs. K., a 54-year-old, recently menopausal woman. She complains of severe hot flashes and night sweats that disturb her sleep. She has had asymptomatic uterine fibroids for about 10 years and, although she would like to take menopausal hormone therapy, she is worried that the medication will make the fibroids larger.

How do you advise these two women?

OCs. OCs do not appear to influence the growth of fibroids. One study found a slightly increased risk of fibroids, another study found no increased risk, and a third found a decreased risk.18,19 These studies are retrospective, however, and may be marked by selection bias.

Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. Postmenopausal hormone therapy does not ordinarily cause fibroid growth. After 3 years, only three of 34 (8%) post-menopausal women who had fibroids and were treated with 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and 5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) a day had any increase in the size of fibroids.20 If any increase in the size of the uterus is noted, it is likely related to progestins.

A study found that 23% of women taking oral estrogen plus 2.5 mg of MPA a day for 1 year had a slight increase in the size of fibroids, whereas 50% of women taking 5 mg of MPA had an increase in size (mean increase in diameter, 3.2 cm).21 Transdermal estrogen plus oral MPA was shown, after 1 year, to cause, on average, a 0.5-cm increase in the diameter of fibroids; oral estrogen and MPA caused no increase in size.22

CASES RESOLVED Rx: Reassurance

Advise Mrs. J. that taking an OC is unlikely to make her fibroids grow larger.

Mrs. K., who is older, can seek relief from postmenopausal symptoms by taking hormone therapy without fear of her fibroids being stimulated to grow.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

CASE 1 Rapid growth=cancer?

Mrs. G., 47 years old, has had uterine fibroids the size of a 12-week pregnancy for about 6 years. At today’s examination, however, her uterus feels about the size of a 16-week pregnancy.

She is aware that her abdomen is bigger, and she complains of some abdominal pressure and urinary frequency. She reports no abnormal bleeding and no abdominal pain.

Mrs. G. is upset because another physician told her she might have cancer and needs a hysterectomy immediately. She tells you that she does not want a hysterectomy unless “it’s absolutely necessary.”

Ultrasonography at this visit reveals that two of the three fibroids noted on a previous sonogram have grown—one from 6 cm to 9 cm in diameter; the other from 5 cm to 8 cm.

What do you tell Mrs. G.?

Understanding myomas

Uterine fibroids, also called myomas, are benign, monoclonal tumors of the myometrium that contain collagen, fibronectin, and proteoglycan. The collagen fibrils are abnormally formed and in disarray; they look like the collagen found in keloids.1 Although the precise causes of fibroids are unknown, hormonal, genetic, and growth factors appear to be involved in their development and growth.2,3

About 40% of fibroids are chromosomally abnormal; the remaining 60% may have undetected mutations. More than 100 genes have been found to be up-regulated or down-regulated in fibroid cells. Many of these genes appear to regulate cell growth, differentiation, proliferation, and mitogenesis.

- A myoma is benign tumor of the myometrium

- In a premenopausal woman, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates the presence of uterine sarcoma

- In an older woman who experiences uterine growth, abdominal pain, and irregular vaginal bleeding, pelvic malignancy may be suspected; an increased level of LDH isoenzyme 3 with increased gadolinium uptake on MRI within 40 to 60 seconds suggests a diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma

- Most fibroids have no impact on fertility, but submucosal fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removing them increases fertility

- Location, size, number, and extent of myoma penetration into the myometrium can be evaluated by pelvic MRI, with coronal, axial, and sagittal images without gadolinium contrast

- Given the risks associated with surgery and the lack of proof of efficacy, myomectomy to improve fertility should be undertaken with caution

- Most myomas do not grow during pregnancy. Unfavorable pregnancy outcomes are very rare in women with myomas.

- Oral contraceptives and postmenopausal hormone therapy almost never influence fibroid growth. Women with fibroids can usually use these therapies safely.

Differentiating benign myoma from uterine sarcoma

Myomas have chromosomal rearrangements similar to other benign lesions, whereas leiomyosarcomas are undifferentiated and have complex chromosomal rearrangements not seen in myomas.4 Genetic differences between myomas and leiomyosarcomas indicate they most likely have distinct origins, and that leiomyosarcomas do not result from malignant degeneration of myomas.2

In premenopausal women, rapid uterine growth almost never indicates uterine sarcoma: One study found only one sarcoma among 371 (0.26%) women operated on for rapid growth of a presumed myoma, and no sarcomas were found in the 198 women who had a 6-week-pregnancy-equivalent increase in uterine size over 1 year.5

Clinical indications. The clinical signs that would lead to suspicion of pelvic malignancy are:

- older age

- abdominal pain

- irregular vaginal bleeding.6

The average age of 2,098 women with uterine sarcoma reported in the SEER (Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results) cancer database from 1989 to 1999 was 63 years, whereas a review of the literature found a mean age of 36 years in women subjected to myomectomy who did not have sarcoma.3,7

Diagnostic tests. The distinction between benign myoma and leiomyosarcoma need not be based on clinical signs alone. Preoperative diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma may be possible, using laboratory values of total serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and LDH isoenzyme 3 plus gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan (Gd-DTPA), with initial images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. A study of 87 women with fibroids, 10 women with leiomyosarcoma, and 130 women with degenerating fibroids reported 100% specificity, 100% positive predictive value, 100% negative predictive value, and 100% diagnostic accuracy for leiomyosarcoma with this combination diagnostic procedure.8

CASE 1 RESOLVED What advice for Mrs. G.?

You order a gadolinium-enhanced, dynamic MRI scan and have blood drawn for total LDH and LDH isoenzymes. Total LDH and isoenzyme 3 are normal. MRI shows no increased enhancement of the fibroids on images taken 40 to 60 seconds after injection of gadolinium. You advise the patient that there is no evidence of cancer (sarcoma) and no urgent need for hysterectomy. You also tell her that, because she is symptomatic, myomectomy is an option that will preserve her uterus.

CASE 2 Fibroids, and contemplating childbearing

Mrs. H., a 35-year-old nulligravida, comes to the office for her first visit with you. She has no complaints, but your pelvic examination reveals a 10 week-size enlarged uterus. A sonogram shows a 6-cm subserosal fibroid and a 3-cm intramural fibroid near the endometrial cavity (see FIGURE). This patient was recently married and wants to become pregnant within the coming year.

When you tell Mrs. H. that she has fibroids, she grows concerned. She asks: “Will this affect my fertility, or a pregnancy?” and “Do I need surgery?”

You explain that the larger, subserosal fibroid is not a concern. The smaller, intramural fibroid could, however, have an impact on fertility and pregnancy if it distorts the uterine cavity.

To find out if that is the case, you order a saline infusion sonogram, which demonstrates, clearly, a normal cavity without distortion by the fibroid.

What is your advice to this woman?

Submucous fibroids that distort the uterine cavity decrease fertility; removal increases fertility. Otherwise, neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids appear to affect the fertility rate; removal has not been shown to increase fertility. Meta-analysis of 11 studies found that submucous myomas that distort the uterine cavity appear to decrease the pregnancy rate by 70% (relative risk [RR], 0.32; confidence interval [CI], 0.13–0.70).9

Assessing the uterine cavity. Evaluating a woman with fibroids for fertility requires reliable assessment of the uterine cavity. Hysteroscopy and saline infusion sonography have been shown to be far superior to transvaginal sonography or hysterosalpingography for detecting submucosal fibroids.10

The best modality for determining the extent of submucosal penetration of a myoma into the myometrium is MRI. It is also an excellent modality for evaluating the size, position, and number of multiple fibroids.11 The drawback to using MRI? It is more costly than other modalities.

Note: Classification of submucosal fibroids is based on the fraction of the mass within the cavity:

- Class 0 myomas are entirely intracavitary

- Class I myomas have 50% or more of the fibroid within the cavity

- Class II myomas have less than 50% within the cavity.12

Resection and fertility. Submucous fibroids can often be removed hysteroscopically. Systematic review of the evidence found that resection-restored fertility is equal to that of infertile controls undergoing in vitro fertilization who do not have fibroids (RR, 1.72; CI, 1.13–2.58).9 In that review, the presence of neither intramural nor subserosal fibroids decreased fertility (intramural: RR, 0.94, and CI, 0.73–1.20; subserosal: RR, 1.1, and CI, 0.06–1.72). Furthermore, removal of intramural and subserosal myomas by abdominal or laparoscopic myomectomy did not improve fertility. An updated unpublished meta-analysis, including studies published after 2001, came to the same conclusion (Pritts E, personal communication, 2008).

CASE 2: Subserosal, intramural myomas cause concern

In a woman contemplating childbearing, does a subserosal (left) or intramural (right) myoma present a problem because of potential to distort the uterine cavity?

Fibroids and pregnancy

The incidence of sonographically detected fibroids during pregnancy is low.13 Among 12,600 women at a prenatal clinic, routine second-trimester sonography identified myomas in 183 (mean age, 33 years)—an incidence of 1.5%.

Pregnancy has a variable and unpredictable effect on myoma growth, likely dependent on individual differences in genetics, circulating growth factors, and myoma-localized receptors. Most myomas do not, however, grow during pregnancy. A prospective study of pregnant women who had a single myoma found that 69% had no increase in volume throughout their pregnancy. In women who were noted to have an increase in the volume of their myoma, the greatest growth occurred before 10 weeks’ gestation. No relationship was found between initial myoma volume and myoma growth during the gestational period. 14

Do myomas complicate pregnancy?

Very rarely. Two studies reported on outcomes in large populations of pregnant women who were examined with routine second-trimester ultrasonography, with follow-up and delivery at the same institution.

In one of those studies, 12,600 pregnant women were evaluated, and the outcome in 167 women who were given a diagnosis of myoma was compared with the outcome in women who did not have a myoma.15 Despite similar clinical management between the two groups, no significant differences were seen in regard to the incidence of:

- preterm delivery

- premature rupture of membranes

- fetal growth restriction

- placenta previa

- placental abruption

- postpartum hemorrhage

- retained placenta.

Only cesarean section was more common among women with fibroids (23% vs 12%).

The second study reviewed 15,104 pregnancies and compared 401 women found to have myomas and the remaining women who did not.16 Although the presence of myoma did not increase the risk of premature rupture of membranes, operative vaginal delivery, chorioamnionitis, or endomyometritis, there was some increased risk of pre-term delivery (19.2% vs 12.7%), placenta previa (3.5% vs 1.8%), and post-partum hemorrhage (8.3% vs 2.9%). Cesarean section was, again, more common (49.1% vs 21.4%).

Do myomas injure the fetus?

Fetal injury as a consequence of fibroids has been reported very infrequently. A review of the literature from 1980 to 2005 revealed only four cases—one each of:

- fetal head anomalies with fetal growth restriction

- postural deformity

- limb reduction

- fetal head deformation with torticollis.17-19

CASE 2 RESOLVED Should Mrs. H. have a myomectomy?

Probably not. Abdominal and laparoscopic myomectomy involve substantial operative and anesthetic risks, including infection, postoperative adhesions, a very small risk of uterine rupture during pregnancy, and increased likelihood of cesarean section. Costs are also substantial, involving not only the expense of surgery, but also patient discomfort and time for recovery. Therefore, until it is proved that intramural myomas decrease fertility and myomectomy increases fertility, surgery should be undertaken with caution. As far as the effects of myoma on pregnancy are concerned, no data are available by which to compare pregnancy outcomes following myomectomy with pregnancy outcomes in women whose myomas are untreated. Randomized studies are needed to clarify these important issues.

CASES 3 & 4 The effects of oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy

Mrs. J. is a 32-year-old G0P0 woman who has a 5-cm fundal myoma. She is sexually active and wants to use an oral contraceptive (OC). She has heard from friends, however, that taking an OC makes fibroids grow, and she asks for your advice.

The same day, you see Mrs. K., a 54-year-old, recently menopausal woman. She complains of severe hot flashes and night sweats that disturb her sleep. She has had asymptomatic uterine fibroids for about 10 years and, although she would like to take menopausal hormone therapy, she is worried that the medication will make the fibroids larger.

How do you advise these two women?

OCs. OCs do not appear to influence the growth of fibroids. One study found a slightly increased risk of fibroids, another study found no increased risk, and a third found a decreased risk.18,19 These studies are retrospective, however, and may be marked by selection bias.

Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy. Postmenopausal hormone therapy does not ordinarily cause fibroid growth. After 3 years, only three of 34 (8%) post-menopausal women who had fibroids and were treated with 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen (CEE) and 5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA) a day had any increase in the size of fibroids.20 If any increase in the size of the uterus is noted, it is likely related to progestins.

A study found that 23% of women taking oral estrogen plus 2.5 mg of MPA a day for 1 year had a slight increase in the size of fibroids, whereas 50% of women taking 5 mg of MPA had an increase in size (mean increase in diameter, 3.2 cm).21 Transdermal estrogen plus oral MPA was shown, after 1 year, to cause, on average, a 0.5-cm increase in the diameter of fibroids; oral estrogen and MPA caused no increase in size.22

CASES RESOLVED Rx: Reassurance

Advise Mrs. J. that taking an OC is unlikely to make her fibroids grow larger.

Mrs. K., who is older, can seek relief from postmenopausal symptoms by taking hormone therapy without fear of her fibroids being stimulated to grow.

1. Stewart EA, Friedman AJ, Peck K, Nowak RA. Relative overexpression of collagen type I and collagen type III messenger ribonucleic acids by uterine leiomyomas during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:900-906.

2. Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1037-1054.

3. Parker W. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:725-736.

4. Quade BJ, Wang TY, Sornberger K, Dal Cin P, Mutter GL, Morton CC. Molecular pathogenesis of uterine smooth muscle tumors from transcriptional profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40:97-108.

5. Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:414-418.

6. Boutselis JG, Ullery JC. Sarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1962;20:23-35.

7. Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989-1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:204-208.

8. Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K, Maruo T. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:354-361.

9. Pritts EA. Fibroids and infertility: a systematic review of the evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:483-491.

10. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:350-357.

11. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Olesen F. Imaging techniques for evaluation of the uterine cavity and endometrium in premenopausal patients before minimally invasive surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:388-403.

12. Cohen LS, Valle RF. Role of vaginal sonography and hysterosonography in the endoscopic treatment of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:197-204.

13. Cooper NP, Okolo S. Fibroids in pregnancy—common but poorly understood. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:132-138.

14. Rosati P, Exacoustos C, Mancuso S. Longitudinal evaluation of uterine myoma growth during pregnancy. A sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:511-515.

15. Vergani P, Ghidini A, Strobelt N, et al. Do uterine leiomyomas influence pregnancy outcome? Am J Perinatol. 1994;11:356-358.

16. Qidwai GI, Caughey AB, Jacoby AF. Obstetric outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:376-382.

17. Joo JG, Inovay J, Silhavy M, Papp Z. Successful enucleation of a necrotizing fibroid causing oligohydramnios and fetal postural deformity in the 25th week of gestation. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:923-925.

18. Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:359-362.

19. Ratner H. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:1027.-

20. Yang CH, Lee JN, Hsu SC, Kuo CH, Tsai EM. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women—a 3-year study. Maturitas. 2002;43:35-39.

21. Palomba S, Sena T, Morelli M, Noia R, Zullo F, Mastrantonio P. Effect of different doses of progestin on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:199-201.

22. Sener AB, Seçkin NC, Ozmen S, Gökmen O, Dogu N, Ekici E. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:354-357.

1. Stewart EA, Friedman AJ, Peck K, Nowak RA. Relative overexpression of collagen type I and collagen type III messenger ribonucleic acids by uterine leiomyomas during the proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:900-906.

2. Flake GP, Andersen J, Dixon D. Etiology and pathogenesis of uterine leiomyomas: a review. Environ Health Perspect. 2003;111:1037-1054.

3. Parker W. Etiology, symptomatology, and diagnosis of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2007;87:725-736.

4. Quade BJ, Wang TY, Sornberger K, Dal Cin P, Mutter GL, Morton CC. Molecular pathogenesis of uterine smooth muscle tumors from transcriptional profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2004;40:97-108.

5. Parker WH, Fu YS, Berek JS. Uterine sarcoma in patients operated on for presumed leiomyoma and rapidly growing leiomyoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:414-418.

6. Boutselis JG, Ullery JC. Sarcoma of the uterus. Obstet Gynecol. 1962;20:23-35.

7. Brooks SE, Zhan M, Cote T, Baquet CR. Surveillance, epidemiology, and end results analysis of 2677 cases of uterine sarcoma 1989-1999. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;93:204-208.

8. Goto A, Takeuchi S, Sugimura K, Maruo T. Usefulness of Gd-DTPA contrast-enhanced dynamic MRI and serum determination of LDH and its isozymes in the differential diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma from degenerated leiomyoma of the uterus. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2002;12:354-361.

9. Pritts EA. Fibroids and infertility: a systematic review of the evidence. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2001;56:483-491.

10. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Hansen ES, Ledertoug S, Olesen F. Evaluation of the uterine cavity with magnetic resonance imaging, transvaginal sonography, hysterosonographic examination, and diagnostic hysteroscopy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:350-357.

11. Dueholm M, Lundorf E, Olesen F. Imaging techniques for evaluation of the uterine cavity and endometrium in premenopausal patients before minimally invasive surgery. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002;57:388-403.

12. Cohen LS, Valle RF. Role of vaginal sonography and hysterosonography in the endoscopic treatment of uterine myomas. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:197-204.

13. Cooper NP, Okolo S. Fibroids in pregnancy—common but poorly understood. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2005;60:132-138.

14. Rosati P, Exacoustos C, Mancuso S. Longitudinal evaluation of uterine myoma growth during pregnancy. A sonographic study. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:511-515.

15. Vergani P, Ghidini A, Strobelt N, et al. Do uterine leiomyomas influence pregnancy outcome? Am J Perinatol. 1994;11:356-358.

16. Qidwai GI, Caughey AB, Jacoby AF. Obstetric outcomes in women with sonographically identified uterine leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:376-382.

17. Joo JG, Inovay J, Silhavy M, Papp Z. Successful enucleation of a necrotizing fibroid causing oligohydramnios and fetal postural deformity in the 25th week of gestation. A case report. J Reprod Med. 2001;46:923-925.

18. Ross RK, Pike MC, Vessey MP, Bull D, Yeates D, Casagrande JT. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:359-362.

19. Ratner H. Risk factors for uterine fibroids: reduced risk associated with oral contraceptives. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;293:1027.-

20. Yang CH, Lee JN, Hsu SC, Kuo CH, Tsai EM. Effect of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women—a 3-year study. Maturitas. 2002;43:35-39.

21. Palomba S, Sena T, Morelli M, Noia R, Zullo F, Mastrantonio P. Effect of different doses of progestin on uterine leiomyomas in postmenopausal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:199-201.

22. Sener AB, Seçkin NC, Ozmen S, Gökmen O, Dogu N, Ekici E. The effects of hormone replacement therapy on uterine fibroids in postmenopausal women. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:354-357.

IN THIS ARTICLE