User login

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

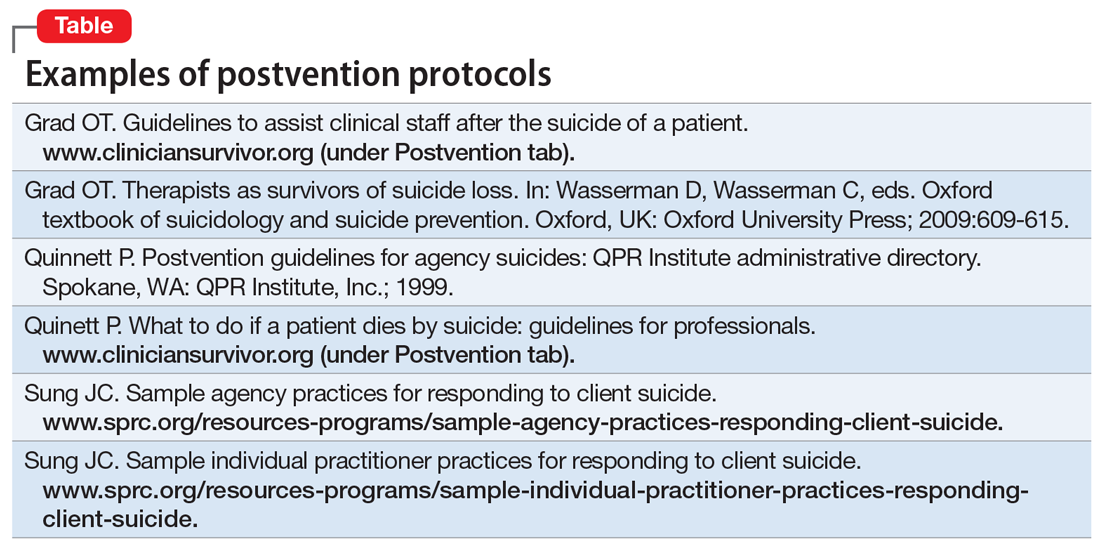

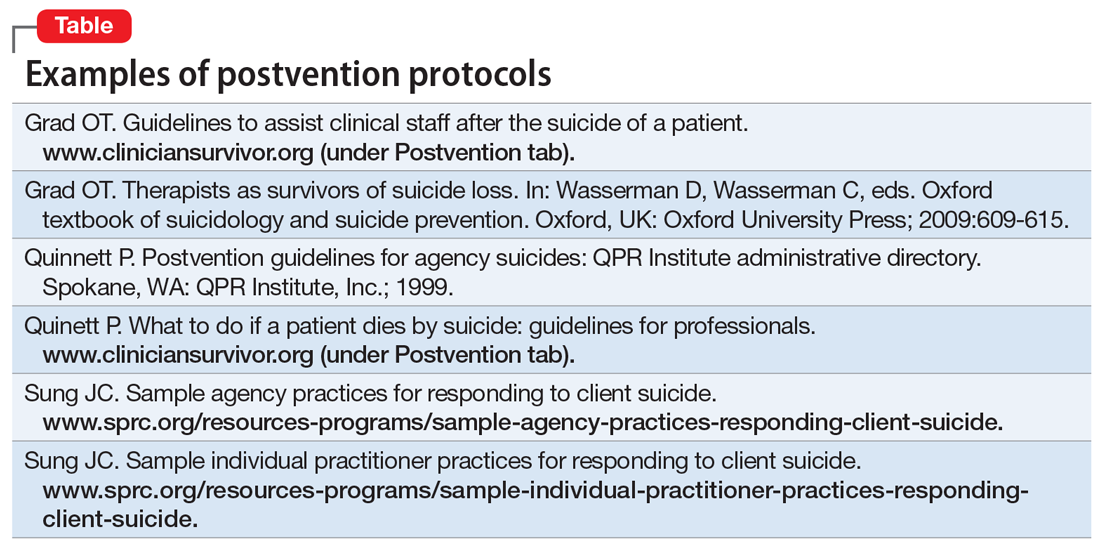

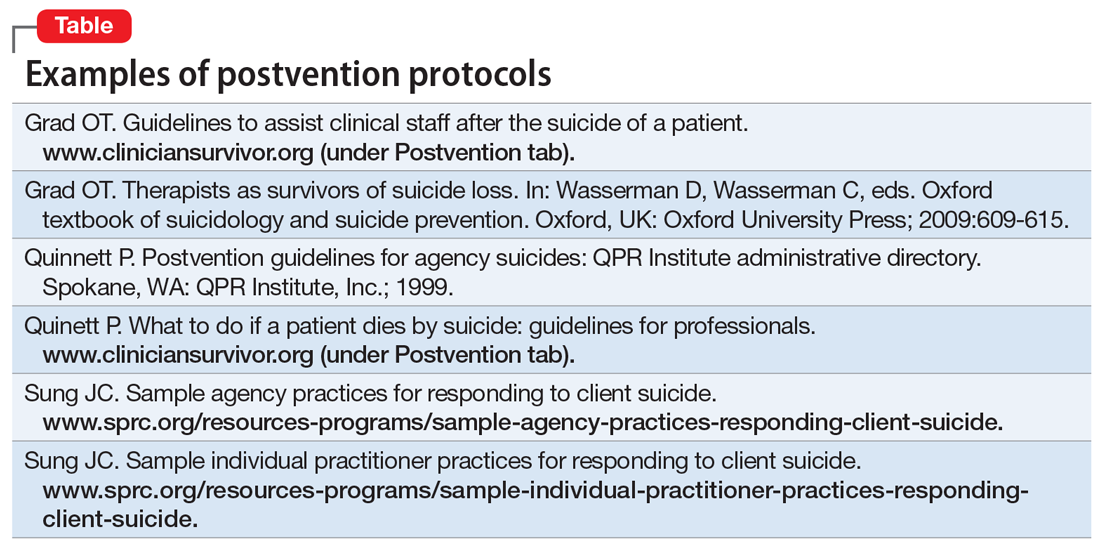

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

At some point during their career, many mental health professionals will lose a patient to suicide, but few will be prepared for the experience and its aftermath. As I described in Part 1 of this article (

A chance for growth

Traumatic experiences such as a suicide loss can paradoxically present a multitude of opportunities for new growth and profound personal transformation.1 Such transformation is primarily fostered by social support in the aftermath of the trauma.2

Virtually all of the models of the clinician’s suicide grief trajectory I described in Part 1 not only assume the eventual resolution of the distressing reactions accompanying the original loss, but also suggest that mastery of these reactions can be a catalyst for both personal and professional growth. Clearly, not everyone who experiences such a loss will experience subsequent growth; there are many reports of clinicians leaving the field3 or becoming “burned out” after this occurs. Yet most clinicians who have described this loss in the literature and in discussion groups (including those I’ve conducted) have reported more positive eventual outcomes. It is difficult to establish whether this is due to a cohort effect—clinicians who are most likely to write about their experiences, be interviewed for research studies, and/or to seek out and participate in discussion/support groups may be more prone to find benefits in this experience, either by virtue of their nature or through the subsequent process of sharing these experiences in a supportive atmosphere.

The literature on patient suicide loss, as well as anecdotal reports, confirms that clinicians who experience optimal support are able to identify many retrospective benefits of their experience.4-6 Clinicians generally report that they are better able to identify potential risk and protective factors for suicide, and are more knowledgeable about optimal interventions with individuals who are suicidal. They also describe an increased sensitivity towards patients who are suicidal and those bereaved by suicide. In addition, clinicians report a reduction in therapeutic grandiosity/omnipotence, and more realistic appraisals and expectations in relation to their clinical competence. In their effort to understand the “whys” of their patient’s suicide, they are likely to retrospectively identify errors in treatment, “missed cues,” or things they might subsequently do differently,7 and to learn from these mistakes. Optimally, clinicians become more aware of their own therapeutic limitations, both in the short- and the long-term, and can use this knowledge to better determine how they will continue their clinical work. They also become much more aware of the issues involved in the aftermath of a patient suicide, including perceived gaps in the clinical and institutional systems that could optimally offer support to families and clinicians.

In addition to the positive changes related to knowledge and clinical skills, many clinicians also note deeper personal changes subsequent to their patient’s suicide, consistent with the literature on posttraumatic growth.1 Munson8 explored internal changes in clinicians following a patient suicide and found that in the aftermath, clinicians experienced both posttraumatic growth and compassion fatigue. He also found that the amount of time that elapsed since the patient’s suicide predicted posttraumatic growth, and the seemingly counterintuitive result that the number of years of clinical experience prior to the suicide was negatively correlated with posttraumatic growth.

Huhra et al4 described some of the existential issues that a clinician is likely to confront following a patient suicide. A clinician’s attempt to find a way to meaningfully understand the circumstances around this loss often prompts reflection on mortality, freedom, choice and personal autonomy, and the scope and limits of one’s responsibility toward others. The suicide challenges one’s previous conceptions and expectations around these professional issues, and the clinician must construct new paradigms that serve to integrate these new experiences and perspectives in a coherent way.

One of the most notable sequelae of this (and to other traumatic) experience is a subsequent desire to make use of the learning inherent in these experiences and to “give back.” Once they feel that they have resolved their own grief process, many clinicians express the desire to support others with similar experiences. Even when their experiences have been quite distressing, many clinicians are able to view the suicide as an opportunity to learn about ongoing limitations in the systems of support, and to work toward changing these in a way that ensures that future clinician-survivors will have more supportive experiences. Many view these new perspectives, and their consequent ability to be more helpful, as “unexpected gifts.” They often express gratitude toward the people and resources that have allowed them to make these transformations. Jones5 noted “the tragedy of patient suicide can also be an opportunity for us as therapists to grow in our skills at assessing and intervening in a suicidal crisis, to broaden and deepen the support we give and receive, to grow in our appreciation of the precious gift that life is, and to help each other live it more fully.”

Continue to: Guidelines for postvention

Guidelines for postvention

When a patient suicide occurs in the context of an agency setting, Grad9 recommends prompt responses on 4 levels:

- administrative

- institutional

- educational

- emotional.

Numerous authors5,10-21 have developed suggestions, guidelines, and detailed postvention protocols to help agencies and clinicians in various mental health settings navigate the often-complicated sequelae to a patient’s suicide. The Table highlights a few of these. Most emphasize that information about suicide loss, including both its statistical likelihood and its potential aftermath, should integrated into clinicians’ general education and training. They also suggest that suicide postvention policies and protocols be in place from the outset, and that such information be incorporated into institutional policy and procedure manuals. In addition, they stress that legal, institutional, and administrative needs be balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Institutional and administrative procedures

The following are some of the recommended procedures that should take place following a suicide loss. The postvention protocols listed in the Table provide more detailed recommendations.

Legal/ethical. It is essential to consult with a legal representative/risk management specialist associated with the affected agency (ideally, one with specific expertise in suicide litigation.). It is also crucial to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death (varies by state), what may and may not be shared under the restrictions of confidentiality and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) laws, and to clarify procedures for chart completion and review. It is also important to clarify the specific information to be shared both within and outside of the agency, and how to address the needs of current patients in the agency settings.

Case review. The optimal purpose of the case review (also known as a psychological autopsy) is to facilitate learning, identify gaps in agency procedures and training, improve pre- and postvention procedures, and help clinicians cope with the loss.22 Again, the legal and administrative needs of the agency need to be balanced with the attention to the emotional impact on the treating clinician.17 Ellis and Patel18 recommend delaying this procedure until the treating clinician is no longer in the “shock” phase of the loss, and is able to think and process events more objectively.

Continue to: Family contact

Family contact. Most authors have recommended that clinicians and/or agencies reach out to surviving families. Although some legal representatives will advise against this, experts in the field of suicide litigation have noted that compassionate family contact reduces liability and facilitates healing for both parties. In a personal communication (May 2008), Eric Harris, of the American Psychological Association Trust, recommended “compassion over caution” when considering these issues. Again, it is important to clarify who holds privilege after a patient’s death in determining when and with whom the patient’s confidential information may be shared. When confidentiality may be broken, clinical judgment should be used to determine how best to present the information to grieving family members.

Even if surviving family members do not hold privilege, there are many things that clinicians can do to be helpful.23 Inevitably, families will want any information that will help them make sense of the loss, and general psychoeducation about mental illness and suicide can be helpful in this regard. In addition, providing information about “Survivors After Suicide” support groups, reading materials, etc., can be helpful. Both support groups and survivor-related bibliographies are available on the web sites of the American Association of Suicidology (www.suicidology.org) and The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (www.afsp.org).

In addition, clinicians should ask the family if it would be helpful if they were to attend the funeral/memorial services, and how to introduce themselves if asked by other attendees.

Patients in clinics/hospitals. When a patient suicide occurs in a clinic or hospital setting, it is likely to impact other patients in that setting to the extent that they have heard, about the event, even from outside sources.According to Hodgkinson,24 in addition to being overwhelmed with intense feelings about the suicide loss (particularly if they had known the patient), affected patients are likely to be at increased risk for suicidal behaviors. This is consistent with the considerable literature on suicide contagion.

Thus, it is important to clarify information to be shared with patients; however, avoid describing details of the method, because this can foster contagion and “copycat” suicides. In addition, Kaye and Soreff22 noted that these patients may now be concerned about the staff’s ability to be helpful to them, because they were unable to help the deceased. In light of this, take extra care to attend to the impact of the suicide on current patients, and to monitor both pre-existing and new suicidality.

Continue to: Helping affected clinicians

Helping affected clinicians

Suggestions for optimally supporting affected clinicians include:

- clear communication about the nature of upcoming administrative procedures (including chart and institutional reviews)

- consultation from supervisors and/or colleagues that is supportive and reassuring, rather than blaming

- opportunities for the clinician to talk openly about the experience of the loss, either individually or in group settings, without fear of judgment or censure

- recognition that the loss is likely to impact clinical work, support in monitoring this impact, and the provision of medical leaves and/or modified caseloads (ie, fewer high-risk patients) as necessary.

Box 1

Frank Jones and Judy Meade founded the Clinical Survivor Task Force (CSTF) of the American Association of Suicidology (AAS) in 1987. As Jones noted, “clinicians who have lost patients to suicide need a place to acknowledge and carry forward their personal loss…to benefit both personally and professionally from the opportunity to talk with other therapists who have survived the loss of a patient through suicide.”7 Nina Gutin, PhD, and Vanessa McGann, PhD, have co-chaired the CSTF since 2003. It supports clinicians who have lost patients and/or loved ones, with the recognition that both types of losses carry implications within clinical and professional domains. The CSTF provides a listserve, opportunities to participate in video support groups, and a web site (www.cliniciansurvivor.org) that provides information about the clinician-survivor experience, the opportunity to read and post narratives about one’s experience with suicide loss, an updated bibliography maintained by John McIntosh, PhD, a list of clinical contacts, and links to several excellent postvention protocols. In addition, Drs. Gutin and McGann conduct clinician-survivor support activities at the annual AAS conference, and in their respective geographic areas.

Both researchers and clinician-survivors in my practice and support groups have noted that speaking with other clinicians who have experienced suicide loss can be particularly reassuring and validating. If none are available on staff, the listserve and online support groups of the American Association of Suicidology’s Clinician Survivor Task Force may be helpful (Box 17). In addition, the film “Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” features physicians describing their experience of losing a patient to suicide (Box 2).

Box 2

“Collateral Damages: The Impact of Patient Suicide on the Physician” is a film that features several physicians speaking about their experience of losing a patient to suicide, as well as a group discussion. Psychiatrists in this educational film include Drs. Glen Gabbard, Sidney Zisook, and Jim Lomax. This resource can be used to facilitate an educational session for physicians, psychologists, residents, or other trainees. Please contact education@afsp.org to request a DVD of this film and a copy of a related article, Prabhakar D, Anzia JM, Balon R, et al. “Collateral damages”: preparing residents for coping with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37(6):429-430.

Schultz14 offered suggestions for staff in supervisory positions, noting that they may bear at least some clinical and legal responsibility for the treatments that they supervise. She encouraged supervisors to take an active stance in advocating for trainees, to encourage colleagues to express their support, and to discourage rumors and other stigmatizing reactions. Schultz also urges supervisors to14:

- allow extra time for the clinician to engage in the normative exploration of the “whys” that are unique to suicide survivors

- use education about suicide to help the clinician gain a more realistic perspective on their relative culpability

- become aware of and provide education about normative grief reactions following a suicide.

Continue to: Because a suicide loss...

Because a suicide loss is likely to affect a clinician’s subsequent clinical activity, Schultz encourages supervisors to help clinicians monitor this impact on their work.14

A supportive environment is key

Losing a patient to suicide is a complicated, potentially traumatic process that many mental health clinicians will face. Yet with comprehensive and supportive postvention policies in place, clinicians who are impacted are more likely to experience healing and posttraumatic growth in both personal and professional domains.

Bottom Line

Although often traumatic, losing a patient to suicide presents clinicians with an opportunity for personal and professional growth. Following established postvention protocols can help ensure that legal, institutional, and administrative needs are balanced with the emotional needs of affected clinicians and staff, as well as those of the surviving family.

Related Resources

- American Association of Suicidology Clinician Survivor Task Force. www.cliniciansurvivor.org.

- Dotinga R. Coping when a patient commits suicide. July 21, 2017. www.mdedge.com/psychiatry/article/142975/depression/coping-when-patient-commits-suicide.

- Gutin N. Losing a patent to suicide: What we know. Part 1. 2019;18(10):14-16,19-22,30-32.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.

1. Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. Beyond the concept of recovery: Growth and the experience of loss. Death Stud. 2008;32(1):27-39.

2. Fuentes MA, Cruz D. Posttraumatic growth: positive psychological changes after trauma. Mental Health News. 2009;11(1):31,37.

3. Gitlin M. Aftermath of a tragedy: reaction of psychiatrists to patient suicides. Psychiatr Ann. 2007;37(10):684-687.

4. Huhra R, Hunka N, Rogers J, et al. Finding meaning: theoretical perspectives on patient suicide. Paper presented at: 2004 Annual Conference of the American Association of Suicidology; April 2004; Miami, FL.

5. Jones FA Jr. Therapists as survivors of patient suicide. In: Dunne EJ, McIntosh JL, Dunne-Maxim K, eds. Suicide and its aftermath: understanding and counseling the survivors. New York, NY: W.W. Norton; 1987;126-141.

6. Gutin N, McGann VM, Jordan JR. The impact of suicide on professional caregivers. In: Jordan J, McIntosh J, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:93-111.

7. Hendin H, Lipschitz A, Maltsberger JT, et al. Therapists’ reactions to patients’ suicides. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(12):2022-2027.

8. Munson JS. Impact of client suicide on practitioner posttraumatic growth [dissertation]. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida; 2009.

9. Grad OT. Therapists as survivors of suicide loss. In: Wasserman D, Wasserman C, eds. Oxford textbook of suicidology and suicide prevention. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2009:609-615.

10. Douglas J, Brown HN. Suicide: understanding and responding: Harvard Medical School perspectives. Madison, CT: International Universities Press; 1989.

11. Farberow NL. The mental health professional as suicide survivor. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2005;2(1):13-20.

12. Plakun EM, Tillman JG. Responding to clinicians after loss of a patient to suicide. Dir Psychiatry. 2005;25:301-310.

13. Quinnett P. QPR: for suicide prevention. QPR Institute, Inc. www.cliniciansurvivor.org (under Postvention tab). Published September 21, 2009. Accessed August 26, 2019.

14. Schultz, D. Suggestions for supervisors when a therapist experiences a client’s suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):59-69.

15. Spiegelman JS Jr, Werth JL Jr. Don’t forget about me: the experiences of therapists-in-training after a patient has attempted or died by suicide. Women Ther. 2005;28(1):35-57.

16. American Association of Suicidology. Clinician Survivor Task Force. Clinicians as survivors of suicide: postvention information. http://cliniciansurvivor.org. Published May 16, 2016. Accessed January 13, 2019.

17. Whitmore CA, Cook J, Salg L. Supporting residents in the wake of patient suicide. The American Journal of Psychiatry Residents’ Journal. 2017;12(1):5-7.

18. Ellis TE, Patel AB. Client suicide: what now? Cogn Behav Pract. 2012;19(2):277-287.

19. Figueroa S, Dalack GW. Exploring the impact of suicide on clinicians: a multidisciplinary retreat model. J Psychiatr Pract. 2013;19(1):72-77.

20. Lerner U, Brooks, K, McNeil DE, et al. Coping with a patient’s suicide: a curriculum for psychiatry residency training programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2012;36(1):29-33.

21. Prabhakar D, Balon R, Anzia J, et al. Helping psychiatry residents cope with patient suicide. Acad Psychiatry. 2014;38(5):593-597.

22. Kaye NS, Soreff SM. The psychiatrist’s role, responses, and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):739-743.

23. McGann VL, Gutin N, Jordan JR. Guidelines for postvention care with survivor families after the suicide of a client. In: Jordan JR, McIntosh JL, eds. Grief after suicide: understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors. New York, NY: Routledge; 2011:133-155.

24. Hodgkinson PE. Responding to in-patient suicide. Br J Med Psychol. 1987;60(4):387-392.