User login

› Initiate pharmacologic treatment for patients

60 years or older with systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg. A

› Start antihypertensive treatment for systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg in patients who are younger than 60 or have chronic kidney disease or diabetes. C

› Select either a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker as first-line therapy for African Americans, whether or not they have diabetes. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Carla S is a 64-year old African American whom you’re seeing for the first time. Her health has been excellent over the last 10 years, she reports, with one caveat: She has “borderline hypertension,” but has never been treated for it and denies any symptoms. Her blood pressure (BP) today is 154/82 mm Hg. A physical exam is unremarkable. Blood tests reveal a normal blood count and normal renal function, and a nonfasting glucose level of 145 mg/dL. You ask Ms. S to return in a week for a repeat BP and fasting lab work.

Hypertension is the most common condition seen by physicians in primary care,1 and a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the morbidity and mortality associated with it. US treatment costs are an estimated $131 billion per year.2-4 With this in mind, the Joint National Committee on Hypertension (JNC) released its eighth report (JNC 8) in December 20131—the first update in a decade.

In many ways, JNC 8 guidelines are simpler than those of JNC 7,2 with more evidence-based recommendations and less reliance on expert opinion. The JNC has eliminated definitions such as stage 1, 2, and 3 hypertension, and focuses on outcomes instead. At the heart of the recommendations are 3 key questions:

1. At what BP should treatment be initiated to improve outcomes?

2. What should the target BP be for those undergoing treatment?

3. Which medications are best?

Answers to the first 2 questions, of course, go hand in hand. In other words, if the threshold for treatment is a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg (more on that in a moment), then the target of treatment is a systolic BP of <140 mm Hg. In answer to the third question, JNC 8 offers guidance but gives physicians greater discretion in determining which type of drug to use when initiating treatment.1

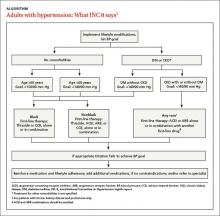

In the text, algorithm, and table that follow, we present an overview of JNC 8. We also discuss the optimal treatment of hypertension in patients with heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD)—populations JNC 8 does not address.

Age-based recommendations are a bit less stringent

60 years and older. Unlike JNC 7, which recommended initiating treatment for otherwise healthy patients of all ages with a BP ≥140/90 mm Hg,2 JNC 8 clearly delineates its recommendations by age. It calls for treating patients ages 60 or older with systolic BP ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90.1

The change is evidence-based: Moderate- to high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found a reduced incidence of stroke, HF, and coronary heart disease when BP was treated to <150/90, but no additional benefit from a systolic BP target of <140 mm Hg for patients in this age group.5,6 Notably, JNC 8 does not recommend a change in medication for patients 60 years or older for whom the more stringent target is being maintained without adverse effects.1

18 to 59 years. For adults younger than 60, JNC 8 recommends treating systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.1 The systolic BP guideline is based on expert opinion, however, as there is no high-quality evidence for a systolic threshold in this age group. This is largely because most patients younger than 60 who have systolic BP ≥140 also have diastolic BP ≥90, making it difficult to study the treatment of systolic BP alone. High-quality trials have shown improved health outcomes when patients ages 30 to 59 years were treated for diastolic BP ≥90, however.7-12 For patients younger than 30, the recommendation for treatment of diastolic pressure is based on expert consensus, as no sufficiently high-quality evidence exists.

Targets for patients with CKD and diabetes

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). JNC 8 recommends treating patients ages 18 to 69 years who have CKD and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg. JNC 7’s more stringent recommendation—treating such patients with BP ≥130/80 mm Hg2—was relaxed because there is little evidence of a lower mortality rate or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular benefits as a result of tighter control. In patients younger than 70, CKD is defined as an estimated (or measured) glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria (>30 mg of albumin per g of creatinine).1

It is important to note that this goal does not apply to individuals who have CKD and are 70 years or older. This is due to insufficient evidence, as well as uncertainty about the accuracy of an estimated GFR in this patient population. JNC 8 recommends that treatment of BP in patients 70 or older be based on comorbidities, including albuminuria, among other patient-specific considerations.1

Diabetes. JNC 8 recommends treating patients age 18 years or older who have diabetes and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, as JNC 7 did.2 This is based largely on expert opinion.

Studies suggest that adults with both hypertension and diabetes have a reduction in mortality and improved cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes when systolic BP is <150 mm Hg,13-15 but no strong data support a goal of <140/90 mm Hg. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) BP trial, for example, showed comparable outcomes in patients with systolic BP of 150 or 140 mm Hg.16 The use of expert opinion vs well-designed studies in this instance seems at odds with JNC 8’s general policy of placing greater emphasis on evidence.

CASE › On her second visit, Ms. S’s BP is 144/82 mm Hg and her cholesterol levels are within the normal range. Her fasting glucose level is 104 mg/dL and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is 6%. At a repeat visit one month later, her BP is 146/76 mm Hg. Given these 2 acceptable readings (<150/90 mm Hg for individuals age 60 and older who do not have diabetes), you do not initiate antihypertensive treatment.

However, you explain to the patient that her fasting glucose and HbA1c are evidence of insulin resistance. Although a diagnosis of diabetes is not warranted, you arrange for Ms. S to meet with a diabetes nurse educator for help in improving her diet and following an exercise regimen.

Pharmacotherapy: JNC 8 offers wider latitude

Like its predecessor, JNC 8 stresses the importance of diet and exercise. (See “Controlling hypertension starts with lifestyle modification”17 in this article.) It diverges from JNC 7, however, in its recommendations for initiating treatment (ALGORITHM).1 The earlier version recommended thiazide diuretics as first-line therapy but included multiple indications for initiating therapy with other drug classes. JNC 8 guidelines are less specific.

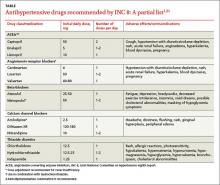

Starting therapy with a thiazide diuretic, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker (CCB)—all of which have high-quality evidence of improved outcomes18-20—is recommended for most patients, including those with diabetes. (Blacks and patients with CKD are exceptions.) The recommended doses of these medications, summarized in the TABLE,1,21 are similar to those used in RCTs. Other types of drugs are not recommended, either because they were shown to be inferior to another class of antihypertensive or because there is insufficient evidence of their efficacy.

For most blacks... JNC 8 recommends thiazide diuretics and CCBs as first-line therapy—a recommendation that is evidence-based. The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)22 revealed that black patients taking thiazide diuretics had fewer cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events and a lower rate of HF compared with those taking ACEIs, whether or not they had diabetes. Diuretics were more effective than CCBs in preventing HF, but no difference in rates of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, kidney disease, or overall mortality was found.22

For patients with CKD and proteinuria, regardless of race, JNC 8 calls for either an ACEI or an ARB as first-line agent to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease. This recommendation is based on expert consensus, and intended to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease.1,23

The optimal first-line agent for patients who have CKD without proteinuria is less clear. For such patients, JNC 8 notes, any of the 4 recommended drug classes can be used for initial therapy.1

Guidance on starting—and titrating—therapy

JNC 7 guidelines featured a complex means of diagnosing and monitoring hypertension.2 JNC 8 has simplified the recommendations, which call for patients to be reassessed within a month of initiating therapy.

The new guidelines include 3 distinct methods of dosing antihypertensive medications, none of which has demonstrated better outcomes than any other. All call for replacing one type of drug with another if the first trial is ineffective or results in adverse effects. And all stress the importance of avoiding ACEI and ARB combinations due to increases in serum creatinine and hyperkalemia and the need for monitoring. Note, however, that Method 3 is recommended for patients with more severe hypertension.1

Method 1. Initiate one medication from any of the 4 classes of antihypertensives recommended for initial treatment, and titrate to the maximum effective dose. If the BP goal is not achieved at maximum dose, add a medication from a second class and titrate that drug to the maximum effective dose, as well. If the goal is still not reached, add a medication from a third class and titrate up as needed.

Method 2. Initiate one medication, then add a second agent from a different drug class, if necessary, and titrate until both are at the maximum effective dose. If the goal still has not been reached, add a third agent and titrate that until BP is well controlled.

Method 3. Initiate 2 medications from 2 different classes of drugs simultaneously. If BP is not at goal after a reasonable trial, add a third agent and titrate to maximum effective dose. (Use this approach for patients who have systolic BP >160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >100 mm Hg or systolic BP >20 mm Hg above goal and/or diastolic BP >10 mm Hg above goal.)

As a general rule, a trial with monotherapy should be considered if BP is ≤160/100; a 2-agent combination is recommended as first-line therapy for pressure that exceeds that threshold. If a patient’s BP target is not reached even with the above strategies, a consultation with a hypertension specialist may be needed.

Treating patients with cardiovascular comorbidities

As noted earlier, JNC 8 offers no guidance in treating patients with HF or CAD and multiple comorbidities. In such cases, we turn to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA).24

Recent ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a beta-blocker and ACEI for patients with a history of symptomatic stable HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤40%, unless contraindications exist.24 Beta-blockers and an ACEI or an ARB should be used to prevent HF in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) or acute coronary syndrome and a reduced EF. Beta-blockers with evidence to support their use in such cases include carvedilol, bisoprolol, and sustained-release metoprolol succinate.24

For symptomatic patients with dyspnea or other mild fluid retention, a loop diuretic or a thiazide diuretic can be used. Nondihydropyridine CCBs should be avoided in post-MI patients with low left ventricular EF due to the medication’s negative inotropic effects.24 The optimal drug regimen for secondary stroke prevention is not clear due to a lack of studies comparing drug regimens, but data suggest that a diuretic or a diuretic-ACEI combination is beneficial.25

Evaluating treatment-resistant hypertension

When a patient presents with treatment-resistant hypertension—elevated BP that is not controlled with a 3-drug regimen, all at maximum doses—start by asking several questions.26 Is the patient:

- having difficulty following a drug regimen that calls for multiple daily doses?

- drinking excessive amounts of alcohol?

- failing to adhere to a low-salt dietary regimen?

- taking any other medications or supplements that might elevate BP (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, pseudoephedrine, ephedra, or licorice)?

- unable to afford all the drugs prescribed?

If no such issues are identified, consider a referral to a specialist for further evaluation and to rule out disorders associated with treatment-resistant hypertension, including CKD, renal artery stenosis, hyperaldosteronemia, sleep apnea, and coarctation of the aorta.26

For most people, cardiovascular health is dependent on exercise and weight control. That’s particularly true for those with hypertension, for whom limiting alcohol and salt consumption is crucial, as well.

JNC 8 calls for lifestyle management,1 but specific recommendations come from the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)’s 2013 Lifestyle Work Group.17 The guidelines call for patients with elevated blood pressure (BP) to follow a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, including low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, legumes, nuts, and nontropical vegetable oils, such as the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) or AHA diet. Salt consumption should not exceed 2400 mg/d—and, ideally, be limited to 1500 mg/d or reflect a reduction of at least 1000 mg/d.17

Stress the importance of regular physical activity in controlling BP, as well. The ACC/AHA call for adults to engage in moderate to vigorous aerobic activity 3 to 4 times a week, averaging about 40 minutes per session.17

CASE › When Ms. S returns 3 months later, her BP is 140/70 mm Hg, her fasting glucose is 94 mg/dL, and her HbA1c is 5.7%. You encourage her to continue her new dietary and exercise regimen and schedule a follow-up visit in 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy D. Mahvan, PharmD, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, Health Sciences Center, Room 292, 1000 East University Avenue, Department 3375, Laramie, WY 82071; tbaher@uwyo.edu

1. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

4. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Arteriosclerosis; Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiopulmonary; Critical Care; Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933-944.

5. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115-2127.

6. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, et al; Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group. Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension. 2010;56:196-202.

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

8. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. III. Reduction in stroke incidence among persons with high blood pressure. JAMA. 1982;247:633-638.

9. Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on stroke recurrence. JAMA. 1974;229:409-418.

10. Medical Research Council Working Party. MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:97-104.

11. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Report by the Management Committee. Lancet. 1980;1:1261-1267.

12. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

13. Curb JD, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, et al; Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Cooperative Research Group. Effect of diuretic-based antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in older diabetic patients with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1996;276:1886-1892.

14. Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, et al; Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:677-684.

15. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703-713.

16. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575-1585.

17. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99.

18. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255-3264.

19. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

20. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

21. Mann JFE. Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension: recommendations. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-drug-therapy-in-primary-essential-hypertension-recommendations. Accessed March 3, 2014.

22. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981-2997.

23. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421-2431.

24. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e319.

25. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; American Heart Assocaition Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

26. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14-26.

› Initiate pharmacologic treatment for patients

60 years or older with systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg. A

› Start antihypertensive treatment for systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg in patients who are younger than 60 or have chronic kidney disease or diabetes. C

› Select either a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker as first-line therapy for African Americans, whether or not they have diabetes. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Carla S is a 64-year old African American whom you’re seeing for the first time. Her health has been excellent over the last 10 years, she reports, with one caveat: She has “borderline hypertension,” but has never been treated for it and denies any symptoms. Her blood pressure (BP) today is 154/82 mm Hg. A physical exam is unremarkable. Blood tests reveal a normal blood count and normal renal function, and a nonfasting glucose level of 145 mg/dL. You ask Ms. S to return in a week for a repeat BP and fasting lab work.

Hypertension is the most common condition seen by physicians in primary care,1 and a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the morbidity and mortality associated with it. US treatment costs are an estimated $131 billion per year.2-4 With this in mind, the Joint National Committee on Hypertension (JNC) released its eighth report (JNC 8) in December 20131—the first update in a decade.

In many ways, JNC 8 guidelines are simpler than those of JNC 7,2 with more evidence-based recommendations and less reliance on expert opinion. The JNC has eliminated definitions such as stage 1, 2, and 3 hypertension, and focuses on outcomes instead. At the heart of the recommendations are 3 key questions:

1. At what BP should treatment be initiated to improve outcomes?

2. What should the target BP be for those undergoing treatment?

3. Which medications are best?

Answers to the first 2 questions, of course, go hand in hand. In other words, if the threshold for treatment is a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg (more on that in a moment), then the target of treatment is a systolic BP of <140 mm Hg. In answer to the third question, JNC 8 offers guidance but gives physicians greater discretion in determining which type of drug to use when initiating treatment.1

In the text, algorithm, and table that follow, we present an overview of JNC 8. We also discuss the optimal treatment of hypertension in patients with heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD)—populations JNC 8 does not address.

Age-based recommendations are a bit less stringent

60 years and older. Unlike JNC 7, which recommended initiating treatment for otherwise healthy patients of all ages with a BP ≥140/90 mm Hg,2 JNC 8 clearly delineates its recommendations by age. It calls for treating patients ages 60 or older with systolic BP ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90.1

The change is evidence-based: Moderate- to high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found a reduced incidence of stroke, HF, and coronary heart disease when BP was treated to <150/90, but no additional benefit from a systolic BP target of <140 mm Hg for patients in this age group.5,6 Notably, JNC 8 does not recommend a change in medication for patients 60 years or older for whom the more stringent target is being maintained without adverse effects.1

18 to 59 years. For adults younger than 60, JNC 8 recommends treating systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.1 The systolic BP guideline is based on expert opinion, however, as there is no high-quality evidence for a systolic threshold in this age group. This is largely because most patients younger than 60 who have systolic BP ≥140 also have diastolic BP ≥90, making it difficult to study the treatment of systolic BP alone. High-quality trials have shown improved health outcomes when patients ages 30 to 59 years were treated for diastolic BP ≥90, however.7-12 For patients younger than 30, the recommendation for treatment of diastolic pressure is based on expert consensus, as no sufficiently high-quality evidence exists.

Targets for patients with CKD and diabetes

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). JNC 8 recommends treating patients ages 18 to 69 years who have CKD and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg. JNC 7’s more stringent recommendation—treating such patients with BP ≥130/80 mm Hg2—was relaxed because there is little evidence of a lower mortality rate or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular benefits as a result of tighter control. In patients younger than 70, CKD is defined as an estimated (or measured) glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria (>30 mg of albumin per g of creatinine).1

It is important to note that this goal does not apply to individuals who have CKD and are 70 years or older. This is due to insufficient evidence, as well as uncertainty about the accuracy of an estimated GFR in this patient population. JNC 8 recommends that treatment of BP in patients 70 or older be based on comorbidities, including albuminuria, among other patient-specific considerations.1

Diabetes. JNC 8 recommends treating patients age 18 years or older who have diabetes and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, as JNC 7 did.2 This is based largely on expert opinion.

Studies suggest that adults with both hypertension and diabetes have a reduction in mortality and improved cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes when systolic BP is <150 mm Hg,13-15 but no strong data support a goal of <140/90 mm Hg. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) BP trial, for example, showed comparable outcomes in patients with systolic BP of 150 or 140 mm Hg.16 The use of expert opinion vs well-designed studies in this instance seems at odds with JNC 8’s general policy of placing greater emphasis on evidence.

CASE › On her second visit, Ms. S’s BP is 144/82 mm Hg and her cholesterol levels are within the normal range. Her fasting glucose level is 104 mg/dL and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is 6%. At a repeat visit one month later, her BP is 146/76 mm Hg. Given these 2 acceptable readings (<150/90 mm Hg for individuals age 60 and older who do not have diabetes), you do not initiate antihypertensive treatment.

However, you explain to the patient that her fasting glucose and HbA1c are evidence of insulin resistance. Although a diagnosis of diabetes is not warranted, you arrange for Ms. S to meet with a diabetes nurse educator for help in improving her diet and following an exercise regimen.

Pharmacotherapy: JNC 8 offers wider latitude

Like its predecessor, JNC 8 stresses the importance of diet and exercise. (See “Controlling hypertension starts with lifestyle modification”17 in this article.) It diverges from JNC 7, however, in its recommendations for initiating treatment (ALGORITHM).1 The earlier version recommended thiazide diuretics as first-line therapy but included multiple indications for initiating therapy with other drug classes. JNC 8 guidelines are less specific.

Starting therapy with a thiazide diuretic, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker (CCB)—all of which have high-quality evidence of improved outcomes18-20—is recommended for most patients, including those with diabetes. (Blacks and patients with CKD are exceptions.) The recommended doses of these medications, summarized in the TABLE,1,21 are similar to those used in RCTs. Other types of drugs are not recommended, either because they were shown to be inferior to another class of antihypertensive or because there is insufficient evidence of their efficacy.

For most blacks... JNC 8 recommends thiazide diuretics and CCBs as first-line therapy—a recommendation that is evidence-based. The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)22 revealed that black patients taking thiazide diuretics had fewer cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events and a lower rate of HF compared with those taking ACEIs, whether or not they had diabetes. Diuretics were more effective than CCBs in preventing HF, but no difference in rates of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, kidney disease, or overall mortality was found.22

For patients with CKD and proteinuria, regardless of race, JNC 8 calls for either an ACEI or an ARB as first-line agent to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease. This recommendation is based on expert consensus, and intended to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease.1,23

The optimal first-line agent for patients who have CKD without proteinuria is less clear. For such patients, JNC 8 notes, any of the 4 recommended drug classes can be used for initial therapy.1

Guidance on starting—and titrating—therapy

JNC 7 guidelines featured a complex means of diagnosing and monitoring hypertension.2 JNC 8 has simplified the recommendations, which call for patients to be reassessed within a month of initiating therapy.

The new guidelines include 3 distinct methods of dosing antihypertensive medications, none of which has demonstrated better outcomes than any other. All call for replacing one type of drug with another if the first trial is ineffective or results in adverse effects. And all stress the importance of avoiding ACEI and ARB combinations due to increases in serum creatinine and hyperkalemia and the need for monitoring. Note, however, that Method 3 is recommended for patients with more severe hypertension.1

Method 1. Initiate one medication from any of the 4 classes of antihypertensives recommended for initial treatment, and titrate to the maximum effective dose. If the BP goal is not achieved at maximum dose, add a medication from a second class and titrate that drug to the maximum effective dose, as well. If the goal is still not reached, add a medication from a third class and titrate up as needed.

Method 2. Initiate one medication, then add a second agent from a different drug class, if necessary, and titrate until both are at the maximum effective dose. If the goal still has not been reached, add a third agent and titrate that until BP is well controlled.

Method 3. Initiate 2 medications from 2 different classes of drugs simultaneously. If BP is not at goal after a reasonable trial, add a third agent and titrate to maximum effective dose. (Use this approach for patients who have systolic BP >160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >100 mm Hg or systolic BP >20 mm Hg above goal and/or diastolic BP >10 mm Hg above goal.)

As a general rule, a trial with monotherapy should be considered if BP is ≤160/100; a 2-agent combination is recommended as first-line therapy for pressure that exceeds that threshold. If a patient’s BP target is not reached even with the above strategies, a consultation with a hypertension specialist may be needed.

Treating patients with cardiovascular comorbidities

As noted earlier, JNC 8 offers no guidance in treating patients with HF or CAD and multiple comorbidities. In such cases, we turn to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA).24

Recent ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a beta-blocker and ACEI for patients with a history of symptomatic stable HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤40%, unless contraindications exist.24 Beta-blockers and an ACEI or an ARB should be used to prevent HF in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) or acute coronary syndrome and a reduced EF. Beta-blockers with evidence to support their use in such cases include carvedilol, bisoprolol, and sustained-release metoprolol succinate.24

For symptomatic patients with dyspnea or other mild fluid retention, a loop diuretic or a thiazide diuretic can be used. Nondihydropyridine CCBs should be avoided in post-MI patients with low left ventricular EF due to the medication’s negative inotropic effects.24 The optimal drug regimen for secondary stroke prevention is not clear due to a lack of studies comparing drug regimens, but data suggest that a diuretic or a diuretic-ACEI combination is beneficial.25

Evaluating treatment-resistant hypertension

When a patient presents with treatment-resistant hypertension—elevated BP that is not controlled with a 3-drug regimen, all at maximum doses—start by asking several questions.26 Is the patient:

- having difficulty following a drug regimen that calls for multiple daily doses?

- drinking excessive amounts of alcohol?

- failing to adhere to a low-salt dietary regimen?

- taking any other medications or supplements that might elevate BP (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, pseudoephedrine, ephedra, or licorice)?

- unable to afford all the drugs prescribed?

If no such issues are identified, consider a referral to a specialist for further evaluation and to rule out disorders associated with treatment-resistant hypertension, including CKD, renal artery stenosis, hyperaldosteronemia, sleep apnea, and coarctation of the aorta.26

For most people, cardiovascular health is dependent on exercise and weight control. That’s particularly true for those with hypertension, for whom limiting alcohol and salt consumption is crucial, as well.

JNC 8 calls for lifestyle management,1 but specific recommendations come from the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)’s 2013 Lifestyle Work Group.17 The guidelines call for patients with elevated blood pressure (BP) to follow a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, including low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, legumes, nuts, and nontropical vegetable oils, such as the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) or AHA diet. Salt consumption should not exceed 2400 mg/d—and, ideally, be limited to 1500 mg/d or reflect a reduction of at least 1000 mg/d.17

Stress the importance of regular physical activity in controlling BP, as well. The ACC/AHA call for adults to engage in moderate to vigorous aerobic activity 3 to 4 times a week, averaging about 40 minutes per session.17

CASE › When Ms. S returns 3 months later, her BP is 140/70 mm Hg, her fasting glucose is 94 mg/dL, and her HbA1c is 5.7%. You encourage her to continue her new dietary and exercise regimen and schedule a follow-up visit in 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy D. Mahvan, PharmD, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, Health Sciences Center, Room 292, 1000 East University Avenue, Department 3375, Laramie, WY 82071; tbaher@uwyo.edu

› Initiate pharmacologic treatment for patients

60 years or older with systolic blood pressure (BP) ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg. A

› Start antihypertensive treatment for systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg in patients who are younger than 60 or have chronic kidney disease or diabetes. C

› Select either a thiazide diuretic or a calcium channel blocker as first-line therapy for African Americans, whether or not they have diabetes. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Carla S is a 64-year old African American whom you’re seeing for the first time. Her health has been excellent over the last 10 years, she reports, with one caveat: She has “borderline hypertension,” but has never been treated for it and denies any symptoms. Her blood pressure (BP) today is 154/82 mm Hg. A physical exam is unremarkable. Blood tests reveal a normal blood count and normal renal function, and a nonfasting glucose level of 145 mg/dL. You ask Ms. S to return in a week for a repeat BP and fasting lab work.

Hypertension is the most common condition seen by physicians in primary care,1 and a major risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and the morbidity and mortality associated with it. US treatment costs are an estimated $131 billion per year.2-4 With this in mind, the Joint National Committee on Hypertension (JNC) released its eighth report (JNC 8) in December 20131—the first update in a decade.

In many ways, JNC 8 guidelines are simpler than those of JNC 7,2 with more evidence-based recommendations and less reliance on expert opinion. The JNC has eliminated definitions such as stage 1, 2, and 3 hypertension, and focuses on outcomes instead. At the heart of the recommendations are 3 key questions:

1. At what BP should treatment be initiated to improve outcomes?

2. What should the target BP be for those undergoing treatment?

3. Which medications are best?

Answers to the first 2 questions, of course, go hand in hand. In other words, if the threshold for treatment is a systolic BP ≥140 mm Hg (more on that in a moment), then the target of treatment is a systolic BP of <140 mm Hg. In answer to the third question, JNC 8 offers guidance but gives physicians greater discretion in determining which type of drug to use when initiating treatment.1

In the text, algorithm, and table that follow, we present an overview of JNC 8. We also discuss the optimal treatment of hypertension in patients with heart failure (HF) and coronary artery disease (CAD)—populations JNC 8 does not address.

Age-based recommendations are a bit less stringent

60 years and older. Unlike JNC 7, which recommended initiating treatment for otherwise healthy patients of all ages with a BP ≥140/90 mm Hg,2 JNC 8 clearly delineates its recommendations by age. It calls for treating patients ages 60 or older with systolic BP ≥150 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP ≥90.1

The change is evidence-based: Moderate- to high-quality randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have found a reduced incidence of stroke, HF, and coronary heart disease when BP was treated to <150/90, but no additional benefit from a systolic BP target of <140 mm Hg for patients in this age group.5,6 Notably, JNC 8 does not recommend a change in medication for patients 60 years or older for whom the more stringent target is being maintained without adverse effects.1

18 to 59 years. For adults younger than 60, JNC 8 recommends treating systolic BP ≥140 and diastolic BP ≥90 mm Hg.1 The systolic BP guideline is based on expert opinion, however, as there is no high-quality evidence for a systolic threshold in this age group. This is largely because most patients younger than 60 who have systolic BP ≥140 also have diastolic BP ≥90, making it difficult to study the treatment of systolic BP alone. High-quality trials have shown improved health outcomes when patients ages 30 to 59 years were treated for diastolic BP ≥90, however.7-12 For patients younger than 30, the recommendation for treatment of diastolic pressure is based on expert consensus, as no sufficiently high-quality evidence exists.

Targets for patients with CKD and diabetes

Chronic kidney disease (CKD). JNC 8 recommends treating patients ages 18 to 69 years who have CKD and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg. JNC 7’s more stringent recommendation—treating such patients with BP ≥130/80 mm Hg2—was relaxed because there is little evidence of a lower mortality rate or cardiovascular or cerebrovascular benefits as a result of tighter control. In patients younger than 70, CKD is defined as an estimated (or measured) glomerular filtration rate (GFR) <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or albuminuria (>30 mg of albumin per g of creatinine).1

It is important to note that this goal does not apply to individuals who have CKD and are 70 years or older. This is due to insufficient evidence, as well as uncertainty about the accuracy of an estimated GFR in this patient population. JNC 8 recommends that treatment of BP in patients 70 or older be based on comorbidities, including albuminuria, among other patient-specific considerations.1

Diabetes. JNC 8 recommends treating patients age 18 years or older who have diabetes and BP ≥140/90 mm Hg, as JNC 7 did.2 This is based largely on expert opinion.

Studies suggest that adults with both hypertension and diabetes have a reduction in mortality and improved cardiovascular and cerebrovascular outcomes when systolic BP is <150 mm Hg,13-15 but no strong data support a goal of <140/90 mm Hg. The Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD) BP trial, for example, showed comparable outcomes in patients with systolic BP of 150 or 140 mm Hg.16 The use of expert opinion vs well-designed studies in this instance seems at odds with JNC 8’s general policy of placing greater emphasis on evidence.

CASE › On her second visit, Ms. S’s BP is 144/82 mm Hg and her cholesterol levels are within the normal range. Her fasting glucose level is 104 mg/dL and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) is 6%. At a repeat visit one month later, her BP is 146/76 mm Hg. Given these 2 acceptable readings (<150/90 mm Hg for individuals age 60 and older who do not have diabetes), you do not initiate antihypertensive treatment.

However, you explain to the patient that her fasting glucose and HbA1c are evidence of insulin resistance. Although a diagnosis of diabetes is not warranted, you arrange for Ms. S to meet with a diabetes nurse educator for help in improving her diet and following an exercise regimen.

Pharmacotherapy: JNC 8 offers wider latitude

Like its predecessor, JNC 8 stresses the importance of diet and exercise. (See “Controlling hypertension starts with lifestyle modification”17 in this article.) It diverges from JNC 7, however, in its recommendations for initiating treatment (ALGORITHM).1 The earlier version recommended thiazide diuretics as first-line therapy but included multiple indications for initiating therapy with other drug classes. JNC 8 guidelines are less specific.

Starting therapy with a thiazide diuretic, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or calcium channel blocker (CCB)—all of which have high-quality evidence of improved outcomes18-20—is recommended for most patients, including those with diabetes. (Blacks and patients with CKD are exceptions.) The recommended doses of these medications, summarized in the TABLE,1,21 are similar to those used in RCTs. Other types of drugs are not recommended, either because they were shown to be inferior to another class of antihypertensive or because there is insufficient evidence of their efficacy.

For most blacks... JNC 8 recommends thiazide diuretics and CCBs as first-line therapy—a recommendation that is evidence-based. The Antihypertensive and Lipid Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT)22 revealed that black patients taking thiazide diuretics had fewer cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events and a lower rate of HF compared with those taking ACEIs, whether or not they had diabetes. Diuretics were more effective than CCBs in preventing HF, but no difference in rates of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, kidney disease, or overall mortality was found.22

For patients with CKD and proteinuria, regardless of race, JNC 8 calls for either an ACEI or an ARB as first-line agent to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease. This recommendation is based on expert consensus, and intended to prevent progression to end-stage renal disease.1,23

The optimal first-line agent for patients who have CKD without proteinuria is less clear. For such patients, JNC 8 notes, any of the 4 recommended drug classes can be used for initial therapy.1

Guidance on starting—and titrating—therapy

JNC 7 guidelines featured a complex means of diagnosing and monitoring hypertension.2 JNC 8 has simplified the recommendations, which call for patients to be reassessed within a month of initiating therapy.

The new guidelines include 3 distinct methods of dosing antihypertensive medications, none of which has demonstrated better outcomes than any other. All call for replacing one type of drug with another if the first trial is ineffective or results in adverse effects. And all stress the importance of avoiding ACEI and ARB combinations due to increases in serum creatinine and hyperkalemia and the need for monitoring. Note, however, that Method 3 is recommended for patients with more severe hypertension.1

Method 1. Initiate one medication from any of the 4 classes of antihypertensives recommended for initial treatment, and titrate to the maximum effective dose. If the BP goal is not achieved at maximum dose, add a medication from a second class and titrate that drug to the maximum effective dose, as well. If the goal is still not reached, add a medication from a third class and titrate up as needed.

Method 2. Initiate one medication, then add a second agent from a different drug class, if necessary, and titrate until both are at the maximum effective dose. If the goal still has not been reached, add a third agent and titrate that until BP is well controlled.

Method 3. Initiate 2 medications from 2 different classes of drugs simultaneously. If BP is not at goal after a reasonable trial, add a third agent and titrate to maximum effective dose. (Use this approach for patients who have systolic BP >160 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP >100 mm Hg or systolic BP >20 mm Hg above goal and/or diastolic BP >10 mm Hg above goal.)

As a general rule, a trial with monotherapy should be considered if BP is ≤160/100; a 2-agent combination is recommended as first-line therapy for pressure that exceeds that threshold. If a patient’s BP target is not reached even with the above strategies, a consultation with a hypertension specialist may be needed.

Treating patients with cardiovascular comorbidities

As noted earlier, JNC 8 offers no guidance in treating patients with HF or CAD and multiple comorbidities. In such cases, we turn to the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and American Heart Association (AHA).24

Recent ACC/AHA guidelines recommend a beta-blocker and ACEI for patients with a history of symptomatic stable HF and a left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) ≤40%, unless contraindications exist.24 Beta-blockers and an ACEI or an ARB should be used to prevent HF in patients with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) or acute coronary syndrome and a reduced EF. Beta-blockers with evidence to support their use in such cases include carvedilol, bisoprolol, and sustained-release metoprolol succinate.24

For symptomatic patients with dyspnea or other mild fluid retention, a loop diuretic or a thiazide diuretic can be used. Nondihydropyridine CCBs should be avoided in post-MI patients with low left ventricular EF due to the medication’s negative inotropic effects.24 The optimal drug regimen for secondary stroke prevention is not clear due to a lack of studies comparing drug regimens, but data suggest that a diuretic or a diuretic-ACEI combination is beneficial.25

Evaluating treatment-resistant hypertension

When a patient presents with treatment-resistant hypertension—elevated BP that is not controlled with a 3-drug regimen, all at maximum doses—start by asking several questions.26 Is the patient:

- having difficulty following a drug regimen that calls for multiple daily doses?

- drinking excessive amounts of alcohol?

- failing to adhere to a low-salt dietary regimen?

- taking any other medications or supplements that might elevate BP (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, pseudoephedrine, ephedra, or licorice)?

- unable to afford all the drugs prescribed?

If no such issues are identified, consider a referral to a specialist for further evaluation and to rule out disorders associated with treatment-resistant hypertension, including CKD, renal artery stenosis, hyperaldosteronemia, sleep apnea, and coarctation of the aorta.26

For most people, cardiovascular health is dependent on exercise and weight control. That’s particularly true for those with hypertension, for whom limiting alcohol and salt consumption is crucial, as well.

JNC 8 calls for lifestyle management,1 but specific recommendations come from the American College of Cardiology (ACC)/American Heart Association (AHA)’s 2013 Lifestyle Work Group.17 The guidelines call for patients with elevated blood pressure (BP) to follow a diet rich in vegetables, fruits, and whole grains, including low-fat dairy, poultry, fish, legumes, nuts, and nontropical vegetable oils, such as the DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) or AHA diet. Salt consumption should not exceed 2400 mg/d—and, ideally, be limited to 1500 mg/d or reflect a reduction of at least 1000 mg/d.17

Stress the importance of regular physical activity in controlling BP, as well. The ACC/AHA call for adults to engage in moderate to vigorous aerobic activity 3 to 4 times a week, averaging about 40 minutes per session.17

CASE › When Ms. S returns 3 months later, her BP is 140/70 mm Hg, her fasting glucose is 94 mg/dL, and her HbA1c is 5.7%. You encourage her to continue her new dietary and exercise regimen and schedule a follow-up visit in 6 months.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tracy D. Mahvan, PharmD, University of Wyoming, School of Pharmacy, Health Sciences Center, Room 292, 1000 East University Avenue, Department 3375, Laramie, WY 82071; tbaher@uwyo.edu

1. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

4. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Arteriosclerosis; Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiopulmonary; Critical Care; Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933-944.

5. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115-2127.

6. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, et al; Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group. Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension. 2010;56:196-202.

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

8. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. III. Reduction in stroke incidence among persons with high blood pressure. JAMA. 1982;247:633-638.

9. Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on stroke recurrence. JAMA. 1974;229:409-418.

10. Medical Research Council Working Party. MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:97-104.

11. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Report by the Management Committee. Lancet. 1980;1:1261-1267.

12. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

13. Curb JD, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, et al; Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Cooperative Research Group. Effect of diuretic-based antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in older diabetic patients with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1996;276:1886-1892.

14. Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, et al; Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:677-684.

15. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703-713.

16. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575-1585.

17. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99.

18. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255-3264.

19. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

20. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

21. Mann JFE. Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension: recommendations. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-drug-therapy-in-primary-essential-hypertension-recommendations. Accessed March 3, 2014.

22. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981-2997.

23. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421-2431.

24. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e319.

25. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; American Heart Assocaition Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

26. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14-26.

1. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

2. Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al; Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206-1252.

3. Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al; American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125:e2-e220.

4. Heidenreich PA, Trogdon JG, Khavjou OA, et al; American Heart Association Advocacy Coordinating Committee; Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Clinical Cardiology; Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; Council on Arteriosclerosis; Thrombosis and Vascular Biology; Council on Cardiopulmonary; Critical Care; Perioperative and Resuscitation; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Forecasting the future of cardiovascular disease in the United States: a policy statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:933-944.

5. JATOS Study Group. Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS). Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115-2127.

6. Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, et al; Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group. Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension. 2010;56:196-202.

7. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

8. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. III. Reduction in stroke incidence among persons with high blood pressure. JAMA. 1982;247:633-638.

9. Hypertension-Stroke Cooperative Study Group. Effect of antihypertensive treatment on stroke recurrence. JAMA. 1974;229:409-418.

10. Medical Research Council Working Party. MRC trial of treatment of mild hypertension: principal results. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291:97-104.

11. The Australian therapeutic trial in mild hypertension. Report by the Management Committee. Lancet. 1980;1:1261-1267.

12. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

13. Curb JD, Pressel SL, Cutler JA, et al; Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program Cooperative Research Group. Effect of diuretic-based antihypertensive treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in older diabetic patients with isolated systolic hypertension. JAMA. 1996;276:1886-1892.

14. Tuomilehto J, Rastenyte D, Birkenhäger WH, et al; Systolic Hypertension in Europe Trial Investigators. Effects of calcium-channel blockade in older patients with diabetes and systolic hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:677-684.

15. UK Prospective Diabetes Study Group. Tight blood pressure control and risk of macrovascular and microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes: UKPDS 38. BMJ. 1998;317:703-713.

16. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, et al; ACCORD Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575-1585.

17. Eckel RH, Jakicic JM, Ard JD, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC guideline on lifestyle management to reduce cardiovascular risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129(25 suppl 2):S76-S99.

18. SHEP Cooperative Research Group. Prevention of stroke by antihypertensive drug treatment in older persons with isolated systolic hypertension. Final results of the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program (SHEP). JAMA. 1991;265:3255-3264.

19. Hypertension Detection and Follow-up Program Cooperative Group. Five-year findings of the hypertension detection and follow-up program. I. Reduction in mortality of persons with high blood pressure, including mild hypertension. JAMA. 1979;242:2562-2571.

20. Effects of treatment on morbidity in hypertension. II. Results in patients with diastolic blood pressure averaging 90 through 114 mm Hg. JAMA. 1970;213:1143-1152.

21. Mann JFE. Choice of drug therapy in primary (essential) hypertension: recommendations. UpToDate Web site. Available at: http://www.uptodate.com/contents/choice-of-drug-therapy-in-primary-essential-hypertension-recommendations. Accessed March 3, 2014.

22. ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: The Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288:2981-2997.

23. Wright JT Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, et al; African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group. Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421-2431.

24. Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, et al; American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;128:e240-e319.

25. Furie KL, Kasner SE, Adams RJ, et al; American Heart Assocaition Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Clinical Cardiology, and Interdisciplinary Council on Quality of Care and Outcomes Research. Stroke. 2011;42:227-276.

26. Weber MA, Schiffrin EL, White WB, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of hypertension in the community: a statement by the American Society of Hypertension and the International Society of Hypertension. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2014;16:14-26.