User login

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

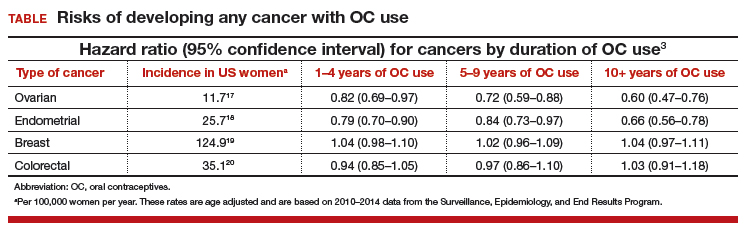

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

EXPERT COMMENTARY

Hormonal contraception (HC), including OC, is a central component of women’s health care worldwide. In addition to its many potential health benefits (pregnancy prevention, menstrual symptom management), HC use modifies the risk of various cancers. As we discussed in the February 2018 issue of OBG Management, a recent large population-based study in Denmark showed a small but statistically significant increase in breast cancer risk in HC users.1,2 Conversely, HC use has a long recognized protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers. These risk relationships may be altered by other modifiable lifestyle characteristics, such as smoking, alcohol use, obesity, and physical activity.

Details of the study

Michels and colleagues evaluated the association between OC use and multiple cancers, stratifying these risks by duration of use and various modifiable lifestyle characteristics.3 The authors used a prospective survey-based cohort (the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study) linked with state cancer registries to evaluate this relationship in a diverse population of 196,536 women across 6 US states and 2 metropolitan areas. Women were enrolled in 1995–1996 and followed until 2011. Cancer risks were presented as hazard ratios (HR), which indicate the risk of developing a specific cancer type in OC users compared with nonusers. HRs differ from relative risks (RR) and odds ratios because they compare the instantaneous risk difference between the 2 groups, rather than the cumulative risk difference over the entire study period.4

Duration of OC use and risk reduction

In this study population, OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of ovarian cancer, and this risk increased with longer duration of use (TABLE). Similarly, long-term OC use was associated with a decreased risk for endometrial cancer. These effects were true across various lifestyle characteristics, including smoking status, alcohol use, body mass index (BMI), and physical activity level.

There was a nonsignificant trend toward increased risk of breast cancer among OC users. The most significant elevation in breast cancer risk was found in long-term users who were current smokers (HR, 1.21 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.01–1.44]). OC use had a minimal effect on colorectal cancer risk.

The bottom line. US women using OCs were significantly less likely to develop ovarian and endometrial cancers compared with nonusers. This risk reduction increased with longer duration of OC use and was true regardless of lifestyle. Conversely, there was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of developing breast cancer in OC users.

Study strengths and weaknesses

The effect on breast cancer risk is less pronounced than that reported in a recent large, prospective cohort study in Denmark, which reported an RR of developing breast cancer of 1.20 (95% CI, 1.14–1.26) among all current or recent HC users.1 These differing results may be due to the US study population’s increased heterogeneity compared with the Danish cohort; potential recall bias in the US study (not present in the Danish study because pharmacy records were used); the larger size of the Danish study (that is, ability to detect very small effect sizes); and lack of information on OC formulation, recency of use, and parity in the US study.

Nevertheless, the significant protective effect against ovarian and endometrial cancers (reported previously in numerous studies) should be a part of totality of cancer risk when counseling patients on any potential increased risk of breast cancer with OC use.

According to the study by Michels and colleagues, overall, women using OCs had a decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancers and a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer.3 Based on this and prior estimates, the overall risk of developing any cancer appears to be lower in OC users than in nonusers.5,6

Consider discussing the points below when counseling women on OC use and cancer risk.

Cancer prevention

- OC use was associated with a significantly decreased risk of both ovarian and endometrial cancers. This effect increased with longer duration of use.

- Ovarian cancer risk reduction persisted regardless of smoking status, BMI, alcohol use, or physical activity level.

- The largest reduction in endometrial cancer was seen in current smokers and patients with a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2.

Breast cancer risk

- There was a trend toward a slightly increased risk of breast cancer with OC use of any duration.

- A Danish cohort study showed a significantly higher risk (although still an overall low risk) of breast cancer with HC use (RR, 1.20 [95% CI, 1.14-1.26]).1

- The differences in these 2 results may be related to study design and population characteristic differences.

Overall cancer risk

- The definitive and larger risk reductions in ovarian and endometrial cancer compared with the lesser risk increase in breast cancer suggest a net decrease in developing any cancer for OC users.3,5,6

Risks of pregnancy prevention failure

- OCs are an effective method for preventing unintended pregnancy. Risks of OCs should be weighed against the risks of unintended pregnancy.

- In the United States, the maternal mortality rate (2015) is 26.4 deaths for every 100,000 women.7 The risk of maternal mortality is substantially higher than even the highest published estimates of HC-attributable breast cancer rates (that is, 13 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women using HC; 2 incremental breast cancers for every 100,000 women 35 years of age or younger using HC).1

- Unintended pregnancy is a serious maternal-child health problem, and it has substantial health, social, and economic consequences.8-14

- Unintended pregnancies generate a significant economic burden (an estimated $21 billion in direct and indirect costs for the US health care system per year).15 Approximately 42% of unintended pregnancies end in abortion.16

-- Dana M. Scott, MD, and Mark D. Pearlman, MD

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@mdedge.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Mørch LS, Skovlund CW, Hannaford PC, Iversen L, Fielding S, Lidegaard Ø. Contemporary hormonal contraception and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2228–2239.

- Scott DM, Pearlman MD. Does hormonal contraception increase the risk of breast cancer? OBG Manag. 2018;30(2):16–17.

- Michels KA, Pfeiffer RM, Brinton LA, Trabert B. Modification of the associations between duration of oral contraceptive use and ovarian, endometrial, breast, and colorectal cancers [published online January 18, 2018]. JAMA Oncol. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.4942.

- Sedgwick P. Hazards and hazard ratios. BMJ. 2012;345:e5980.

- Bassuk SS, Manson JE. Oral contraceptives and menopausal hormone therapy: relative and attributable risks of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and other health outcomes. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(3):193–200.

- Hunter D. Oral contraceptives and the small increased risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(23):2276–2277.

- GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, and national levels of maternal mortality, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1775–1812.

- Brown SS, Eisenberg L, eds. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 1995:50–90.

- Klein JD; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Adolescence. Adolescent pregnancy: current trends and issues. Pediatrics. 2005;116(1):281–286.

- Logan C, Holcombe E, Manlove J, Ryan S; The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy and Child Trends. The consequences of unintended childbearing. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/b353/b02ae6cad716a7f64ca48b3edae63544c03e.pdf?_ga=2.149310646.1402594583.1524236972-1233479770.1524236972&_gac=1.195699992.1524237056. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Sonfield A. The evidence mounts on the benefits of preventing unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2013;87(2):126–127.

- Trussell J, Henry N, Hassan F, Prezioso A, Law A, Filonenko A. Burden of unintended pregnancy in the United States: potential savings with increased use of long-acting reversible contraception. Contraception. 2013;87(2):154–161.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy and infant care: estimates for 2008. Guttmacher Institute. https://www.guttmacher.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/public-costs-of-up.pdf. Published October 2013. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Forrest JD, Singh S. Public-sector savings resulting from expenditures for contraceptive services. Fam Plann Perspect. 1990;22(1):6–15.

- Sonfield A, Kost K. Public costs from unintended pregnancies and the role of public insurance programs in paying for pregnancy-related care: national and state estimates for 2010. Guttmacher Institute. http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/public-costs-of-UP-2010.pdf. Published February 2015. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843–852.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: ovarian cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/ovary.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: uterine cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/corp.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: female breast cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/breast.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.

- Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program. Cancer stat facts: colorectal cancer. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute. http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/colorect.html. Accessed April 20, 2018.