User login

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

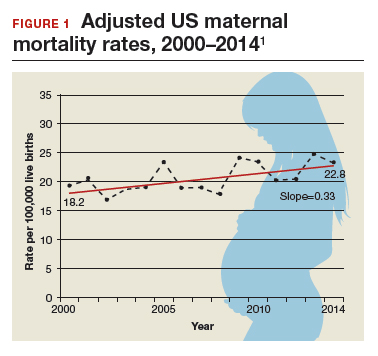

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

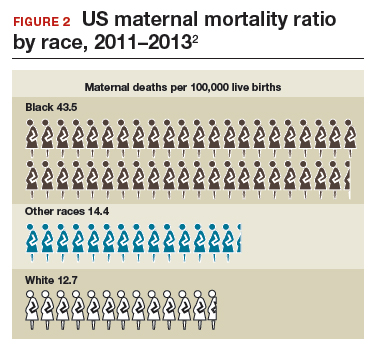

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

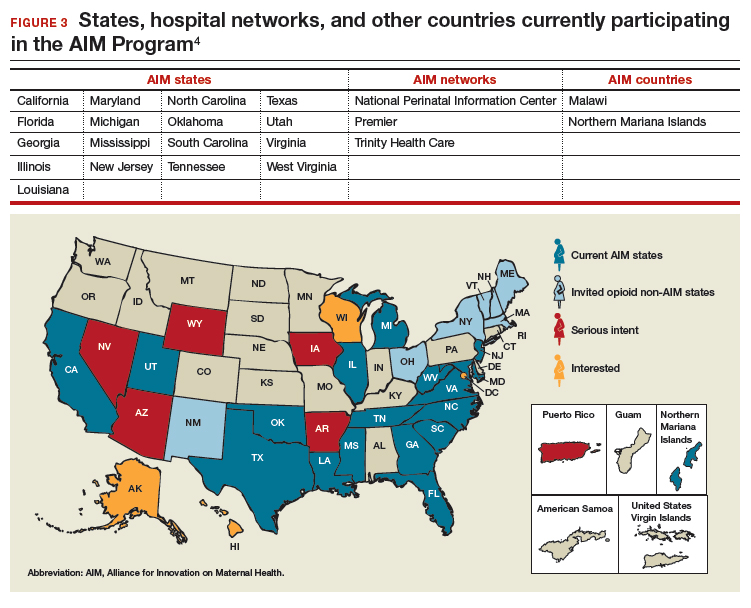

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

More women die from pregnancy complications in the United States than in any other developed country. The United States is the only industrialized nation with a rising maternal mortality rate.

Those 2 sentences should stop us all in our tracks.

In fact, the United States ranks 47th globally with the worst maternal mortality rate. More than half these deaths are likely preventable, with suicide and drug overdose the leading causes of maternal death in many states. All this occurs despite our advanced medical system, premier medical colleges and universities, embrace of high-tech medical advances, and high percentage of gross domestic product spent on health care.

Need more numbers? According to a 2016 report in Obstetrics and Gynecology, the United States saw a 26% increase in the maternalmortality rate (unadjusted) in only 15 years: from 18.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 23.8 in 2014 (FIGURE 1).1

This problem received federal attention when, in 2000, the US Department of Health and Human Services launched Healthy People 2010. That health promotion and disease prevention agenda set a goal of reducing maternal mortality to 3.3 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2010, a goal clearly not met.

Considerable variations by race and by state

The racial disparities in maternal mortality are staggering and have not improved in more than 20 years: African American women are 3.4 times more likely to die than non-Hispanic white women of pregnancy-related complications. In 2011–2013, the maternal mortality ratio for non-Hispanic white women was 12.7 deaths per 100,000 live births compared with 43.5 deaths for non-Hispanic black women (FIGURE 2).2 American Indian or Alaska Native women, Asian women, and some Latina women also experience higher rates than non-Hispanic white women. The rate for American Indian or Alaska Native women is 16.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.3

Some states are doing better than others, showing that there is nothing inevitable about the maternal mortality crisis. Texas, for example, has seen the highest rate of maternal mortality increase. Its rate doubled from 2010 to 2012, while California reduced its maternal death rate by 30%, from 21.5 to 15.1, during roughly the same period.1

This is a challenge of epic proportions, and one that the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), under the leadership of President Haywood Brown, MD, and Incoming President Lisa Hollier, MD, is determined to meet, ensuring that a high maternal death rate does not become our nation’s new normal.

Dr. Brown put it this way, “ACOG collaborative initiatives such as Levels of Maternal Care (LOMC) and implementation of OB safety bundles for hemorrhage, hypertension, and thromboembolism through the AIM [Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health] Program target maternal morbidity and mortality at the community level. Bundles have also been developed to address the disparity in maternal mortality and for the opiate crisis.”

ACOG is making strides in putting in place nationwide meaningful, evidence-driven systems and care approaches that are proven to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity, saving mothers’ lives and keeping families whole.

Read about the AIM Program’s initiatives

ACOG’s AIM Program established to make an impact

The AIM Program (www.safehealthcare foreverywoman.org) is bringing together clinicians, public health officials, hospital administrators, patient safety organizations, and advocates to eliminate preventable maternal mortality throughout the United States. With funding and support from the US Health Resources and Services Administration, AIM is striving to:

- reduce maternal mortality by 1,000 deaths by 2018

- reduce severe maternal morbidity

- assist states and hospitals to improve outcomes

- create and encourage use of maternal safety bundles (evidence-based tool kits to guide the best care).

AIM offers participating physicians and hospitals online learning modules, checklists, work plans, and links to tool kits and published resources. Implementation data is shared with hospitals and states to further improve care. Physicians participating in AIM can receive Part IV maintenance of certification; continuing education units will soon be offered for nurses. In the future, AIM-participating hospitals may be able to receive reduced liability protection costs, too.

To date, 17 states are participating in the AIM initiative (FIGURE 3), with more states ready to enroll.4 States must demonstrate a commitment to lasting change to participate. Each AIM state must have an active maternal mortality review committee (MMRC); committed leadership from public health, hospital associations, and provider associations; and a commitment to report AIM data.

AIM thus far has released 9 obstetric patient safety bundles, including:

- reducing disparities in maternity care

- severe hypertension in pregnancy

- safe reduction of primary cesarean birth

- prevention of venous thromboembolism

- obstetric hemorrhage

- maternal mental health

- patient, family, and staff support following a severe maternal event

- postpartum care basics

- obstetric care of women with opioid use disorder (in use by Illinois, Massachusetts, Maryland, New Jersey, Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New York, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia).

Read about how active MMRCS are critical to success

Review committees are critical to success

In use in many states, MMRCs are groups of local ObGyns, nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals who review specific cases of maternal deaths from their local area and recommend local solutions to prevent future deaths. MMRCs can be a critically important source of data to help us understand the underlying causes of maternal mortality.

Remember California’s success in reducing its maternal mortality rate, previously mentioned? That state was an early adopter of an active MMRC and has worked to bring best practices to maternity care throughout the state.

While every state should have an active MMRC, not every state does. ACOG is working with states, local leaders, and state and federal legislatures to help develop MMRCs in every state.

Dr. Brown pointed out that, “For several decades, Indiana had a legislatively authorized multidisciplinary maternal mortality review committee that I actively participated in and led in the late 1990s. The authorization for the program lapsed in the early 2000s, and the Indiana MMRC had to shut down. Bolstering the federal government’s capacity to help states like Indiana rebuild MMRCs, or start them from scratch, will help state public health officials, hospitals, and physicians take better care of moms and babies.”

Dr. Hollier explained, “In Texas, I chair our Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Task Force, which was legislatively authorized in 2013 in response to the rising rate of maternal death. The detailed state-based maternal mortality reviews provide critical information: verification of vital statistics data, assessment of the causes and contributing factors, and determination of pregnancy relatedness. These reviews identify opportunities for prevention and implementation of the most appropriate interventions to reduce maternal mortality on a local level. Support of essential review functions at the federal level would also enable data to be combined across jurisdictions for national learning that was previously not possible.”

Pending legislation will strengthen efforts

ACOG is working to enact into law the Preventing Maternal Deaths Act, HR 1318 and S1112. This is bipartisan legislation under which the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would help states create or expand MMRCs and will require the Department of Health and Human Services to research ways to reduce disparities in maternal health outcomes.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Jean Mahoney, ACOG’s Senior Director, AIM, for her generous assistance.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.

- MacDorman MF, Declerq E, Cabral H, Morton C. Recent increases in the US maternal mortality rate: disentangling trends from measurement issues. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):447–455.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pmss.html. Updated November 9, 2017. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Singh GK. Maternal mortality in the United States, 1935−2007: Substantial racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, and geographic disparities persist. A 75th Anniversary Publication. Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Rockville, Maryland: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/ourstories/mchb75th/mchb75maternalmortality.pdf. Accessed February 16, 2018.

- Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health Program: AIM states and systems. http://safehealthcareforeverywoman.org/aim-states-systems-2/#link_tab-1513011413196-9. Accessed February 20, 2018.