User login

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”

Unwanted or mistimed pregnancies account for 45% of all pregnancies.1 While there are ramifications for any unintended pregnancy, the risks for patients with mental illness are greater and include potential adverse effects on the neonate from both psychiatric disease and psychiatric medication use, worse obstetrical outcomes for patients with untreated mental illness, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk in the peripartum period.2 These risks become even more pronounced when psychiatric medications are reflexively discontinued or reduced in pregnancy, which is commonly done contrary to best practice recommendations. In the United States, the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization has erased federal protections for abortion previously conferred by Roe v Wade. As a result, as of early October 2022, abortion had been made illegal in 11 states, and was likely to be banned in many others, most commonly in states where there is limited support for either parents or children. Thus, preventing unplanned pregnancies should be a treatment consideration for all medical disciplines.3

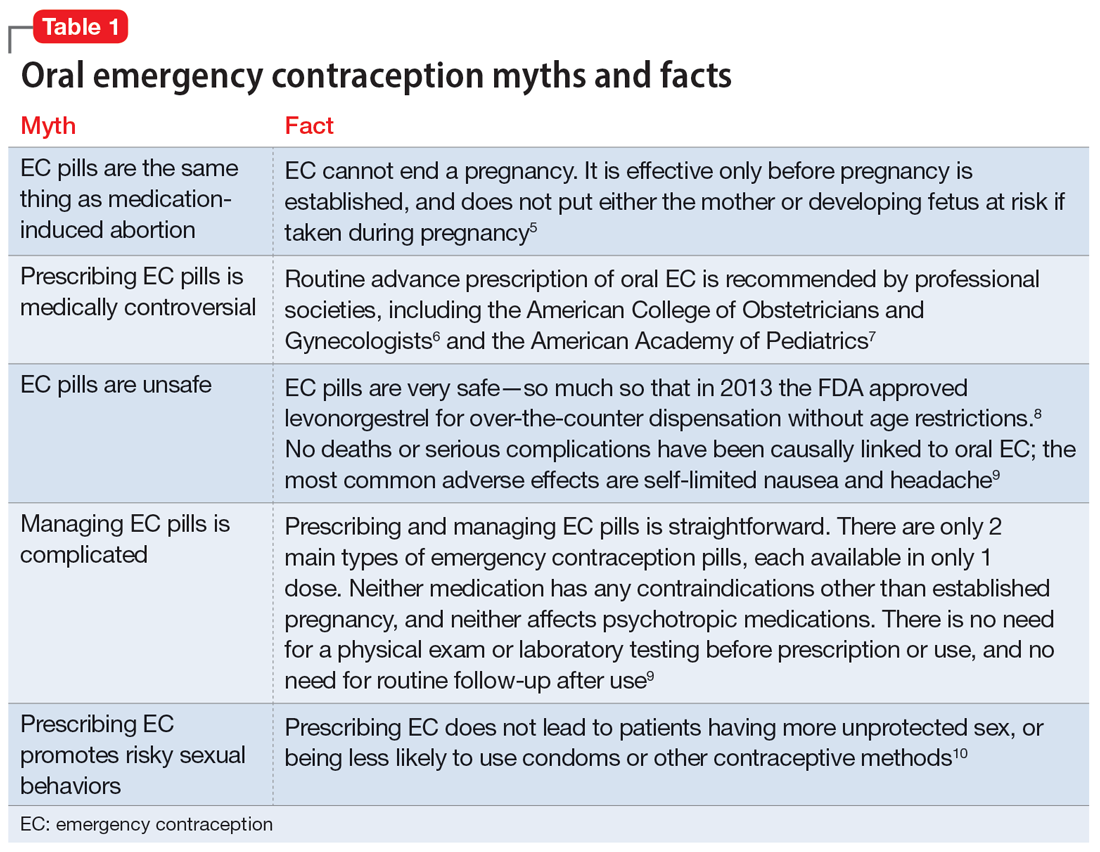

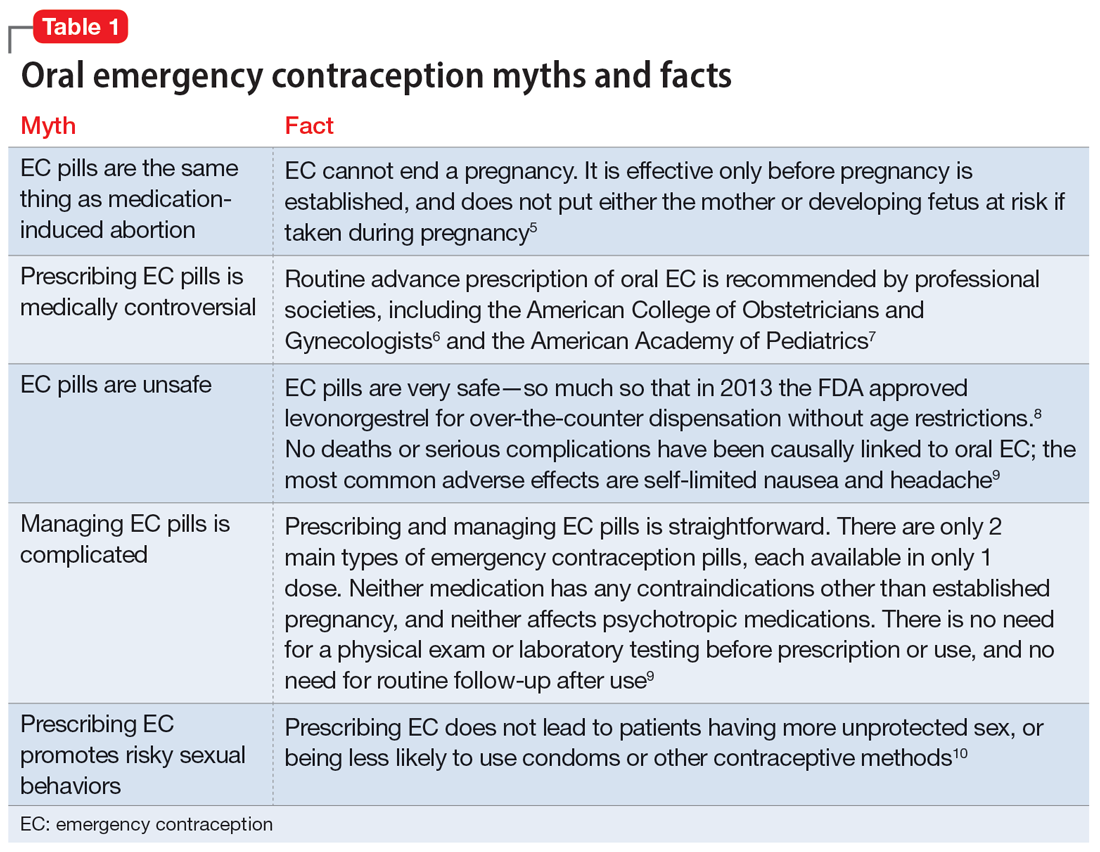

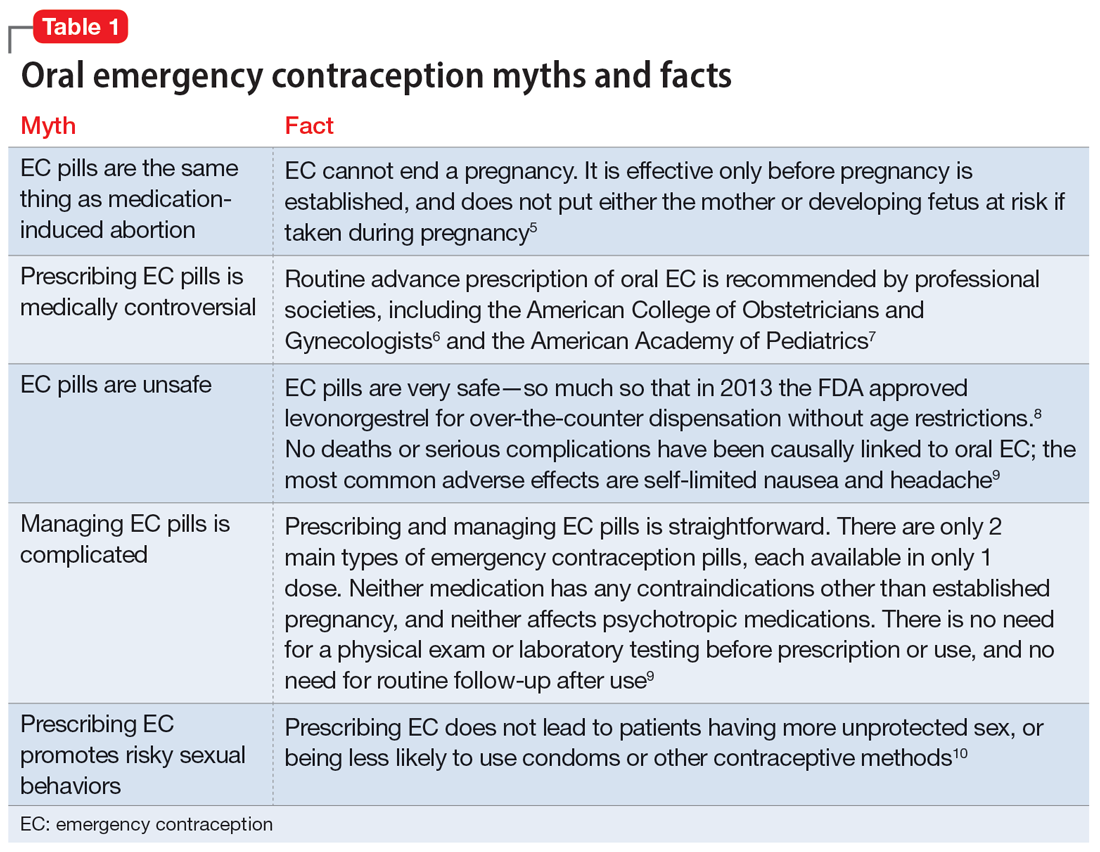

Psychiatrists may hesitate to prescribe emergency contraception (EC) due to fears it falls outside the scope of their practice. However, psychiatry has already moved towards prescribing nonpsychiatric medications when doing so clearly benefits the patient. One example is prescribing metformin to address metabolic syndrome related to the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Emergency contraceptives have strong safety profiles and are easy to prescribe. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to increasing access to emergency contraceptives for psychiatric patients.4 These include the erroneous belief that laboratory and physical exams are needed before starting EC, cost and/or limited stock of emergency contraceptives at pharmacies, and general confusion regarding what constitutes EC vs an oral abortive (Table 15-10). Psychiatrists are particularly well-positioned to support the reproductive autonomy and well-being of patients who struggle to engage with other clinicians. This article aims to help psychiatrists better understand EC so they can comfortably prescribe it before their patients need it.

What is emergency contraception?

EC is medications or devices that patients can use after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy. They do not impede the development of an established pregnancy and thus are not abortifacients. EC is not recommended as a primary means of contraception,9 but it can be extremely valuable to reduce pregnancy risk after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failures such as broken condoms or missed doses of birth control pills. EC can prevent ≥95% of pregnancies when taken within 5 days of at-risk intercourse.11

Methods of EC fall into 2 categories: oral medications (sometimes referred to as “morning after pills”) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). IUDs are the most effective means of EC, especially for patients with higher BMIs or who may be taking medications such as cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 inducers that could interfere with the effectiveness of oral methods. IUDs also have the advantage of providing highly effective ongoing contraception.6 However, IUDs require in-office placement by a trained clinician, and patients may experience difficulty obtaining placement within 5 days of unprotected sex. Therefore, oral medication is the most common form of EC.

Oral EC is safe and effective, and professional societies (including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 and the American Academy of Pediatrics7) recommend routinely prescribing oral EC for patients in advance of need. Advance prescribing eliminates barriers to accessing EC, increases the use of EC, and does not encourage risky sexual behaviors.10

Overview of oral emergency contraception

Two medications are FDA-approved for use as oral EC: ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Both are available in generic and branded versions. While many common birth control pills can also be safely used off-label as emergency contraception (an approach known as the Yuzpe method), they are less effective, not as well-tolerated, and require knowledge of the specific type of pill the patient has available.9 Oral EC appears to work primarily through delay or inhibition of ovulation, and is unlikely to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg.9

Continue to: Ulipristal acetate

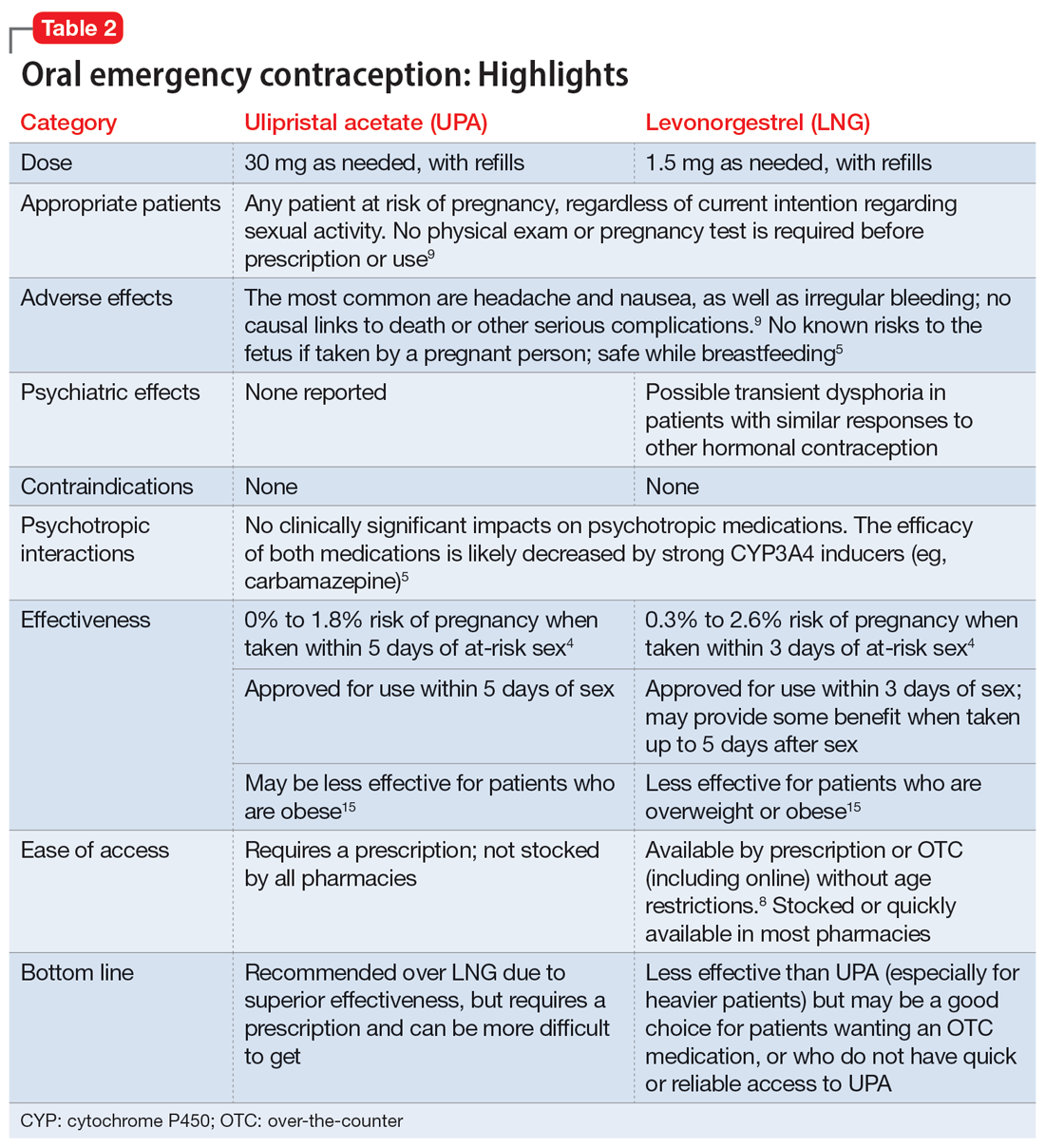

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is an oral progesterone receptor agonist-antagonist taken as a single 30 mg dose up to 5 days after unprotected sex. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by UPA use range from 0% to 1.8%.4 Many pharmacies stock UPA, and others (especially chain pharmacies) report being able to order and fill it within 24 hours.12

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is an oral progestin that is available by prescription and has also been approved for over-the-counter sale to patients of all ages and sexes (without the need to show identification) since 2013.8 It is administered as a single 1.5 mg dose taken as soon as possible up to 3 days after unprotected sex, although it may continue to provide benefits when taken within 5 days. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by LNG use range from 0.3% to 2.6%, with much higher odds among women who are obese.4 LNG is available both by prescription or over-the-counter,13 although it is often kept in a locked cabinet or behind the counter, and staff are often misinformed regarding the lack of age restrictions for sale without a prescription.14

Safety and adverse effects. According to the CDC, there are no conditions for which the risks outweigh the advantages of use of either UPA or LNG,5 and patients for whom hormonal birth control is otherwise contraindicated can still use them safely. If a pregnancy has already occurred, taking EC will not harm the developing fetus; it is also safe to use when breastfeeding.5 Both medications are generally well-tolerated—neither has been causally linked to deaths or serious complications,5 and the most common adverse effects are headache (approximately 19%) and nausea (approximately 12%), in addition to irregular bleeding, fatigue, dizziness, and abdominal pain.15 Oral EC may be used more than once, even within the same menstrual cycle. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be encouraged to discuss more efficacious contraceptive options with their primary physician or gynecologist.

Will oral EC affect psychiatric treatment?

Oral EC is unlikely to have a meaningful effect on psychiatric symptoms or management, particularly when compared to the significant impacts of unintended pregnancies. Neither medication is known to have any clinically significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medications, although the effectiveness of both medications can be impaired by CYP3A4 inducers such as carbamazepine.5 In addition, while research has not specifically examined the impact of EC on psychiatric symptoms, the broader literature on hormonal contraception indicates that most patients with psychiatric disorders generally report similar or lower rates of mood symptoms associated with their use.16 Some women treated with hormonal contraceptives do develop dysphoric mood,16 but any such effects resulting from LNG would likely be transient. Mood disruptions or other psychiatric symptoms have not been associated with UPA use.

How to prescribe oral emergency contraception

Who and when. Women of reproductive age should be counseled about EC as part of anticipatory guidance, regardless of their current intentions for sexual behaviors. Patients do not need a physical examination or pregnancy test before being prescribed or using oral EC.9 Much like how intranasal naloxone is prescribed, prescriptions should be provided in advance of need, with multiple refills to facilitate ready access when needed.

Continue to: Which to prescribe

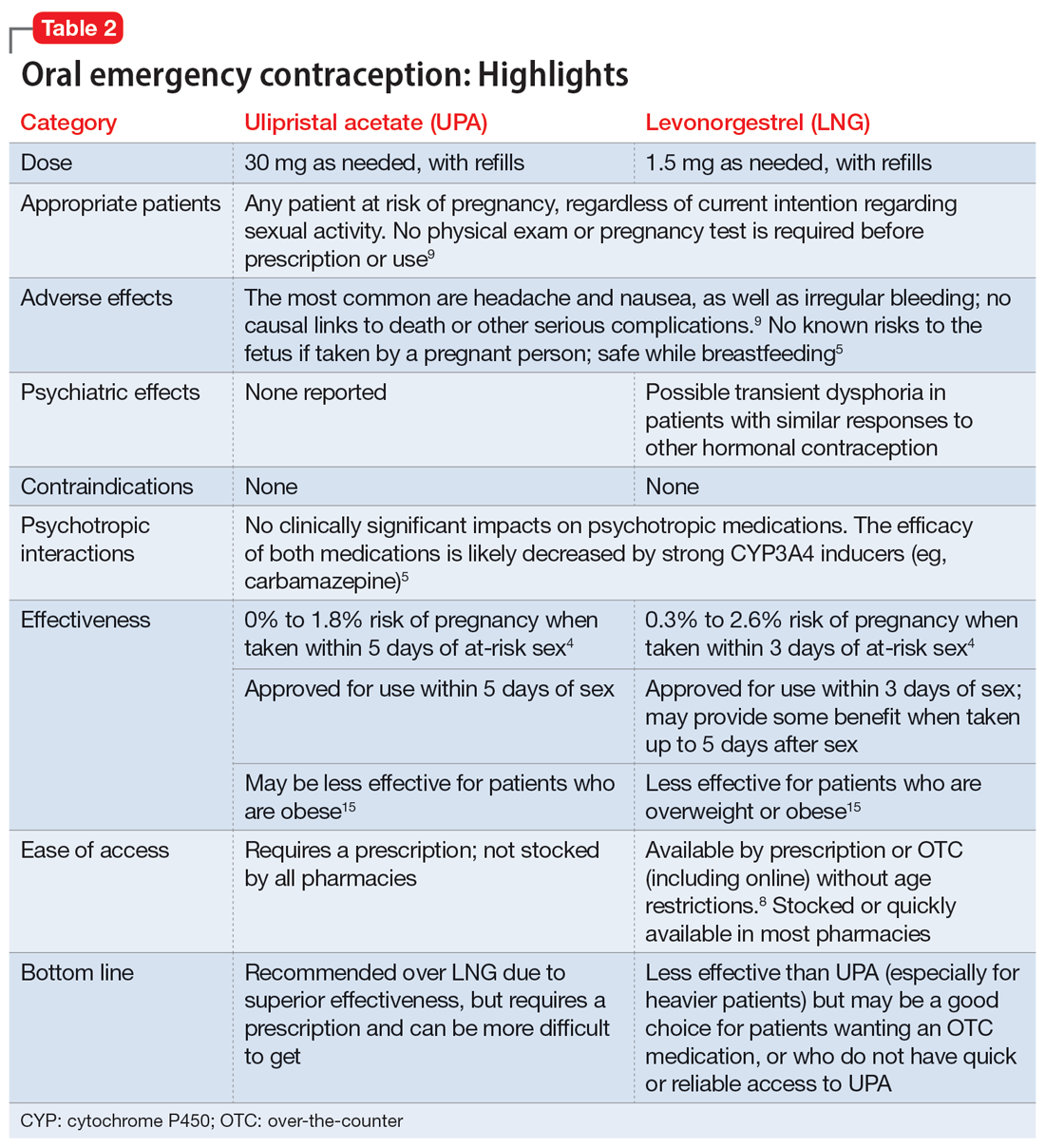

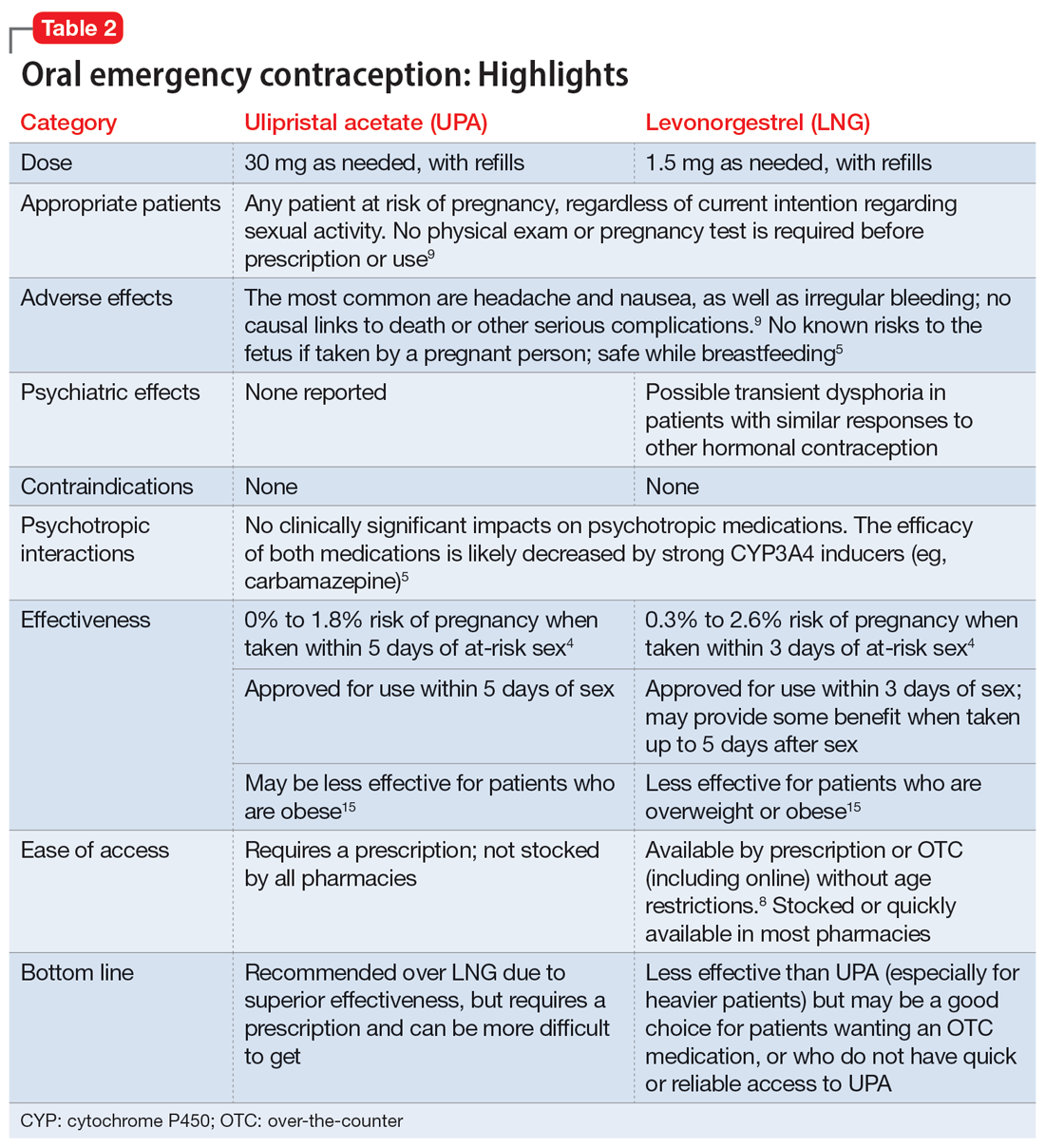

Which to prescribe. UPA is more effective in preventing pregnancy than LNG at all time points up to 120 hours after sex, including for women who are overweight or obese.15 As such, it is recommended as the first-line choice. However, because LNG is available without prescription and is more readily available (including via online order), it may be a good choice for patients who need rapid EC or who prefer a medication that does not require a prescription (Table 24,5,8,9,15).

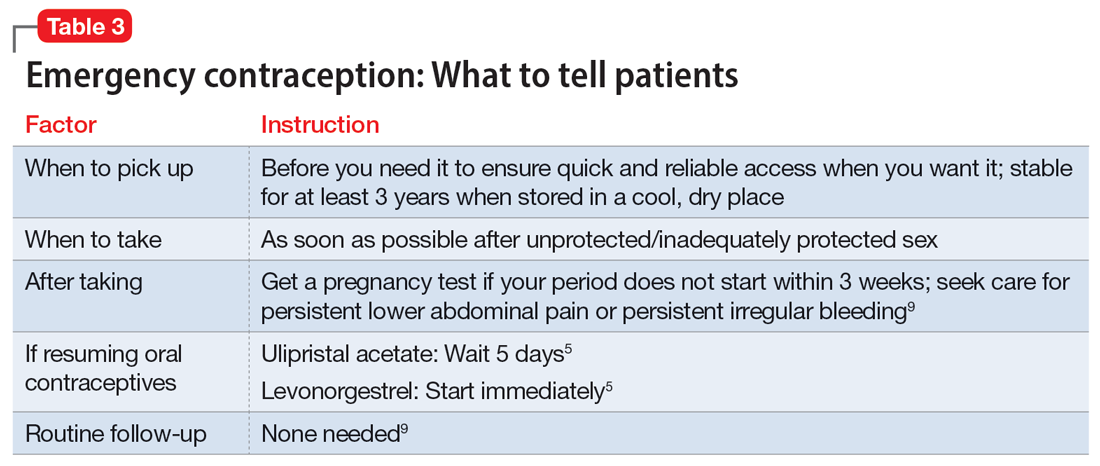

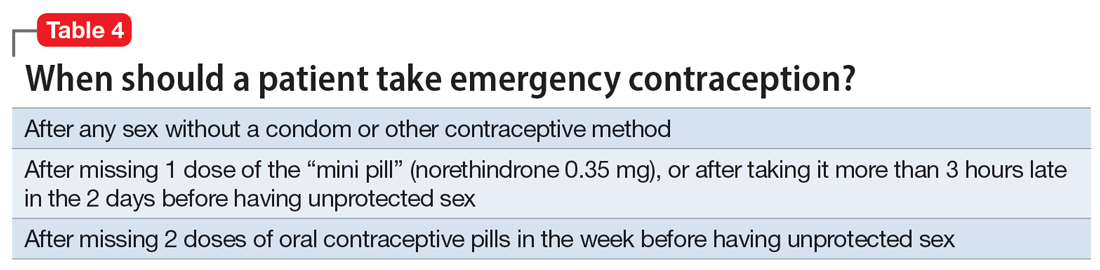

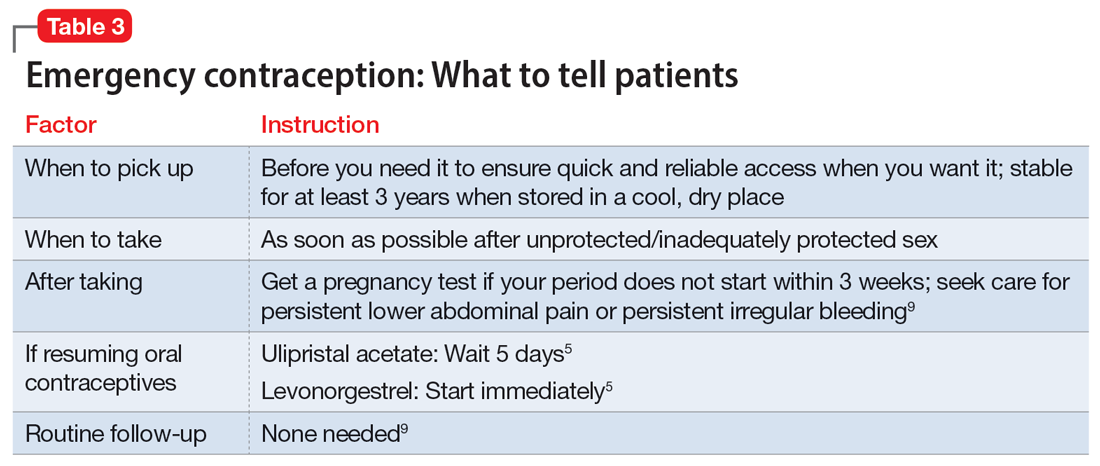

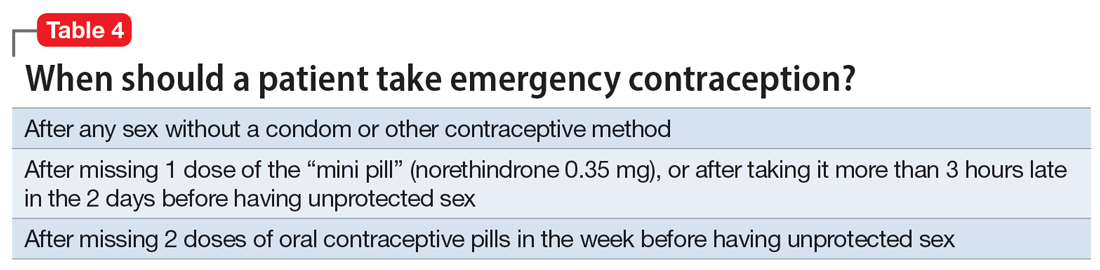

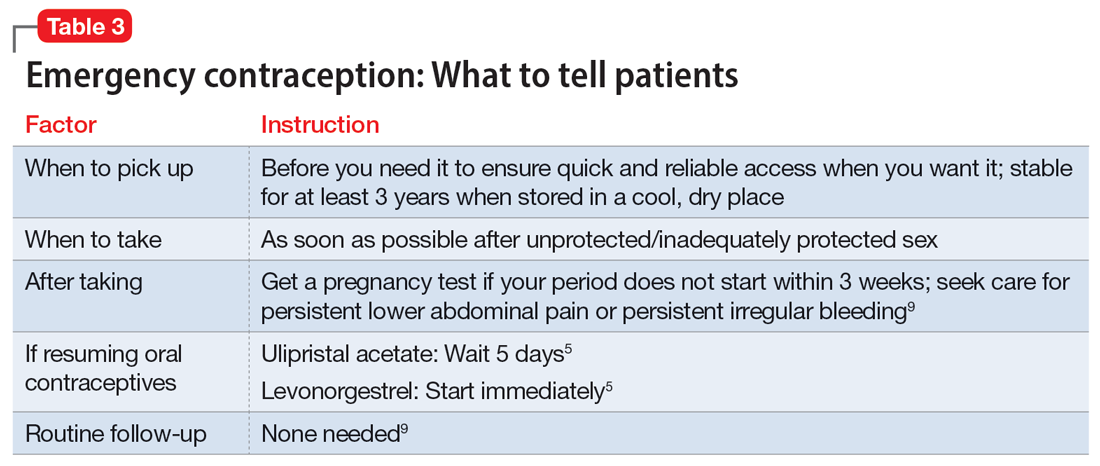

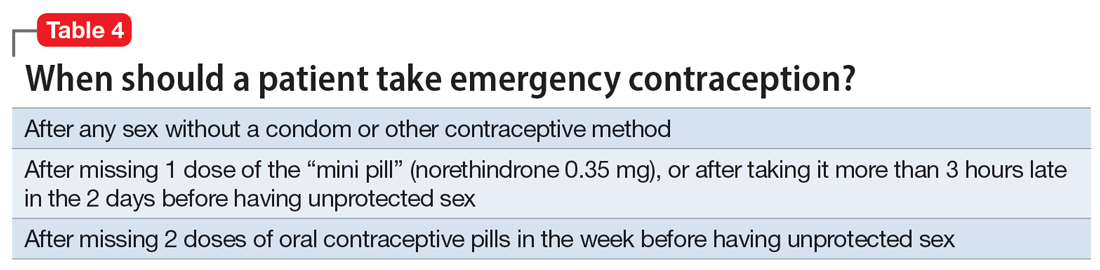

What to tell patients. Patients should be instructed to fill their prescription before they expect to use it, to ensure ready availability when desired (Table 35,9). Oral EC is shelf stable for at least 3 years when stored in a cool, dry environment. Patients should take the medication as soon as possible following at-risk sexual intercourse (Table 4). Tell them that if they vomit within 3 hours of taking the medication, they should take a second dose. Remind patients that EC does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, or from sex that occurs after the medication is taken (in fact, they can increase the possibility of pregnancy later in that menstrual cycle due to delayed ovulation).9 Counsel patients to abstain from sex or to use barrier contraception for 7 days after use. Those who take birth control pills can resume use immediately after using LNG; they should wait 5 days after taking UPA.

No routine follow-up is needed after taking UPA or LNG. However, patients should get a pregnancy test if their period does not start within 3 weeks, and should seek medical evaluation if they experience significant lower abdominal pain or persistent irregular bleeding in order to rule out pregnancy-related complications. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be recommended to pursue routine contraceptive care.

Billing. Counseling your patients about contraception can increase the reimbursement you receive by adding to the complexity of the encounter (regardless of whether you prescribe a medication) through use of the ICD-10 code Z30.0.

Emergency contraception for special populations

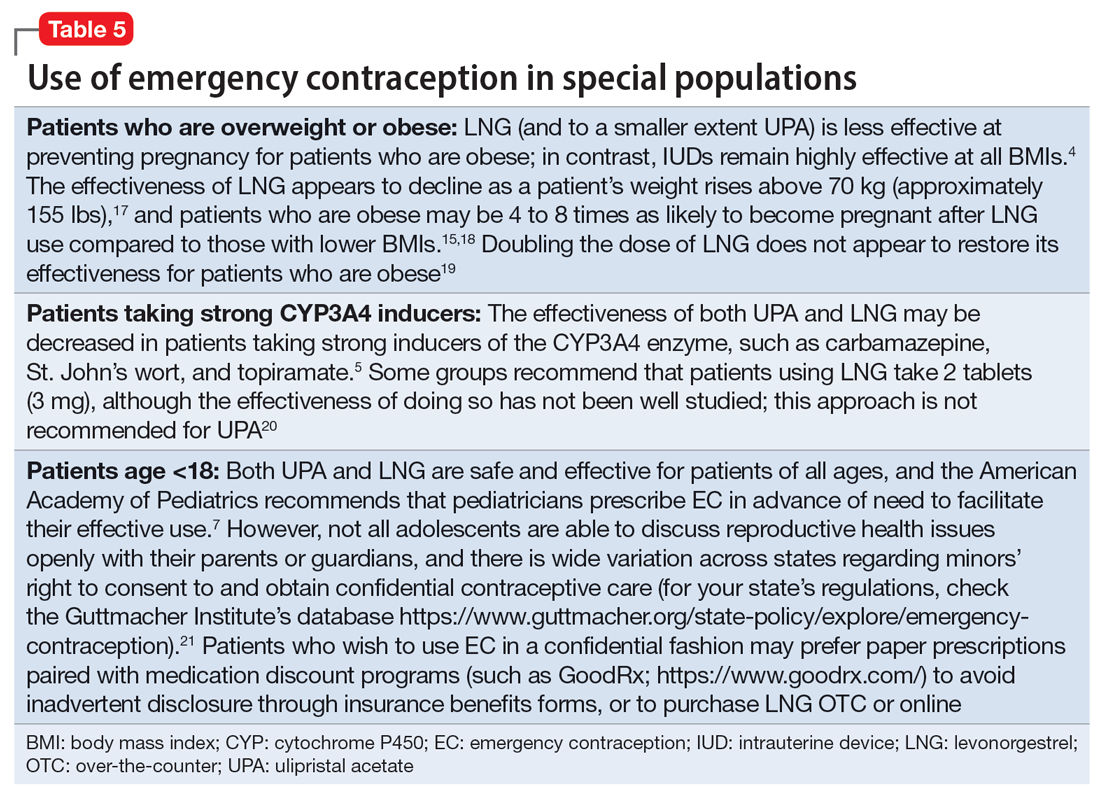

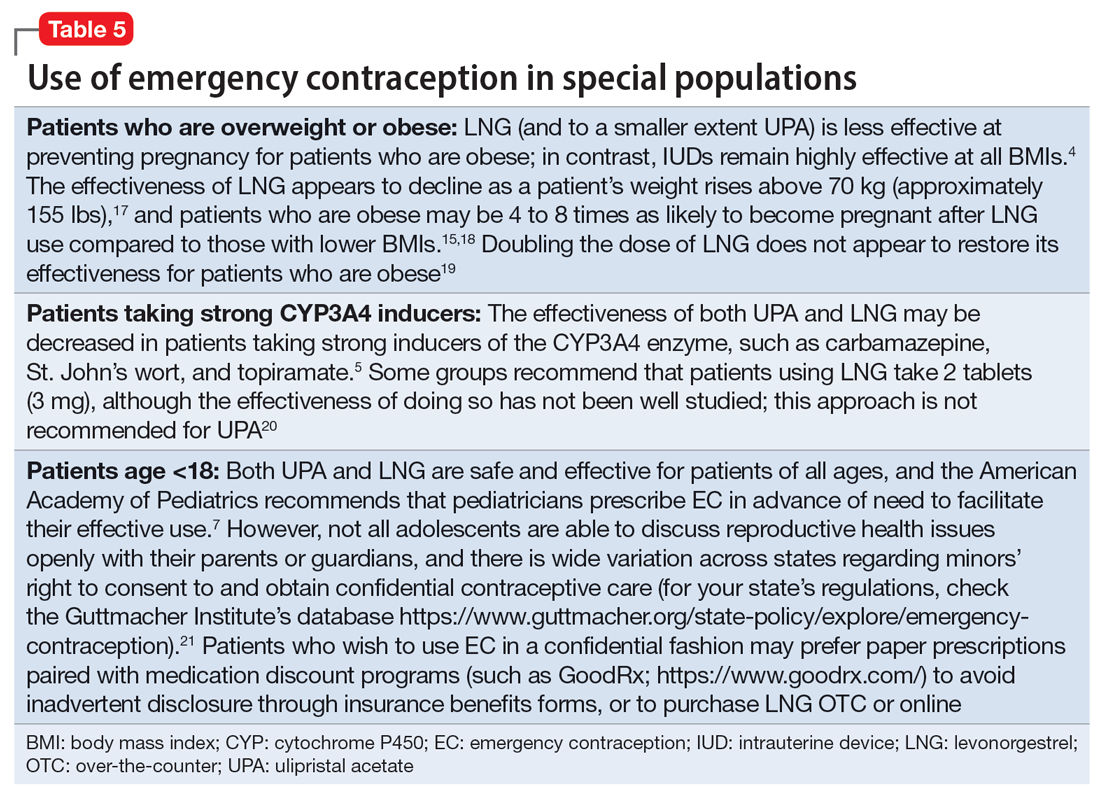

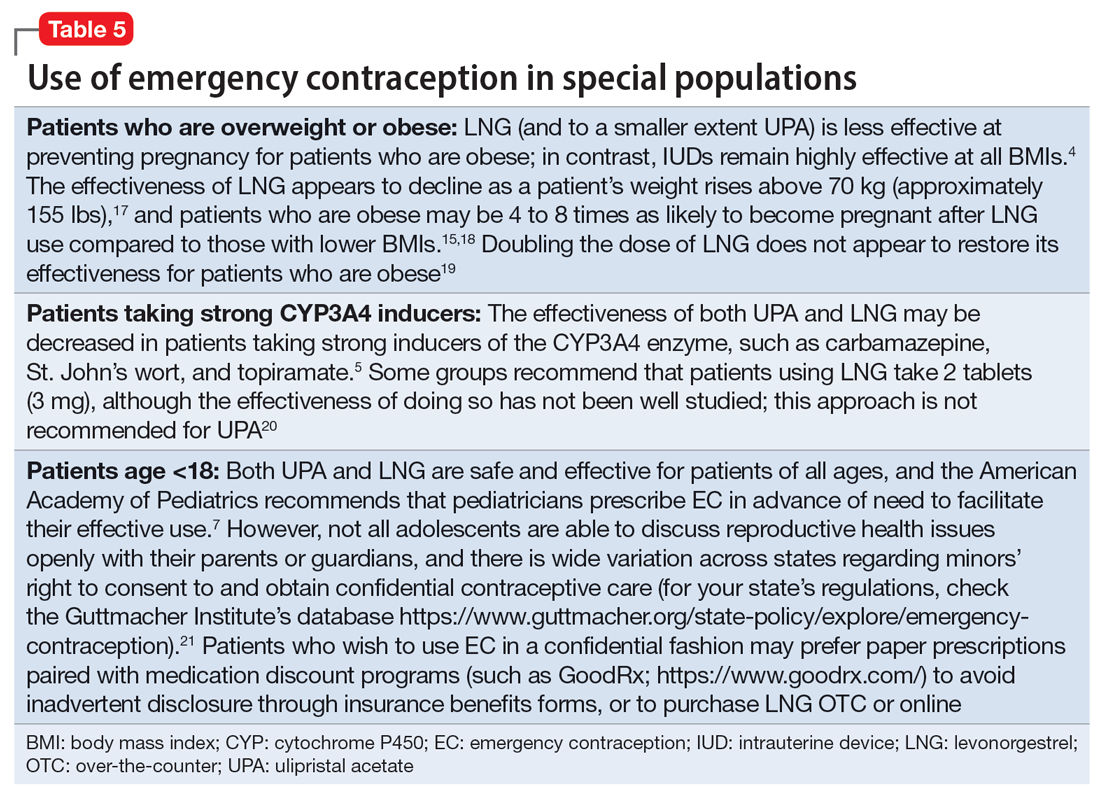

Some patients face additional challenges to effective EC that should be considered when counseling and prescribing. Table 54,5,7,15,17-21 discusses the use of EC in these special populations. Of particular importance for psychiatrists, LNG is less effective at preventing undesired pregnancy among patients who are overweight or obese,15,17,18 and strong CYP3A4-inducing agents may decrease the effectiveness of both LNG and UPA.5 Keep in mind, however, that the advantages of using either UPA or LNG outweigh the risks for all populations.5 Patients must be aware of appropriate information in order to make informed decisions, but should not be discouraged from using EC.

Continue to: Other groups of patients...

Other groups of patients may face barriers due to some clinicians’ hesitancy regarding their ability to consent to reproductive care. Most patients with psychiatric illnesses have decision-making capacity regarding reproductive issues.22 Although EC is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics,7 patients age <18 have varying rights to consent across states,21 and merit special consideration.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. A does not wish to get pregnant at this time, and expresses fears that her recent contraceptive failure could lead to an unintended pregnancy. In addition to her psychiatric treatment, her psychiatrist should discuss EC options with her. She has a healthy BMI and had inadequately protected sex <1 day ago, so her clinician may prescribe LNG (to ensure rapid access for immediate use) in addition to UPA for her to have available in case of future “scares.” The psychiatrist should consider pharmacologic treatment with an antidepressant with a relatively safe reproductive record (eg, sertraline).23 This is considered preventive ethics, since Ms. A is of reproductive age, even if she is not presently planning to get pregnant, due to the aforementioned high rate of unplanned pregnancy.23,24 It is also important for the psychiatrist to continue the dialogue in future sessions about preventing unintended pregnancy. Since Ms. A has benefited from a psychotropic medication when not pregnant, it will be important to discuss with her the risks and benefits of medication should she plan a pregnancy.

Bottom Line

Patients with mental illnesses are at increased risk of adverse outcomes resulting from unintended pregnancies. Clinicians should counsel patients about emergency contraception (EC) as a part of routine psychiatric care, and should prescribe oral EC in advance of patient need to facilitate effective use.

Related Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on Emergency Contraception. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/ articles/2015/09/emergency-contraception

- State policies on emergency contraception. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/emergency-contraception

- State policies on minors’ access to contraceptive services. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

- Patient-oriented contraceptive education materials (in English and Spanish). https://shop.powertodecide.org/ptd-category/educational-materials

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Levonorgestrel • Plan B One-Step, Fallback

Metformin • Glucophage

Naloxone • Narcan

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

Ulipristal acetate • Ella

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Grossman D. Expanding access to short-acting hormonal contraceptive methods in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1209-1210.

2. Gur TL, Kim DR, Epperson CN. Central nervous system effects of prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: sensing the signal through the noise. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227:567-582.

3. Ross N, Landess J, Kaempf A, et al. Pregnancy termination: what psychiatrists need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21:8-9.

4. Haeger KO, Lamme J, Cleland K. State of emergency contraception in the US, 2018. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:20.

5. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-3.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 707: Access to emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e48-e52.

7. Upadhya KK, Breuner CC, Alderman EM, et al. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193149.

8. Rowan A. Obama administration yields to the courts and the evidence, allows emergency contraception to be sold without restrictions. Guttmacher Institute. Published June 25, 2013. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/obama-administration-yields-courts-and-evidence-allows-emergency-contraception-be-sold#

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e1-e11.

10. Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, Gaffield ML, et al. Advance supply of emergency contraception: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:590-601.

11. World Health Organization. Emergency contraception. Published November 9, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/emergency-contraception

12. Shigesato M, Elia J, Tschann M, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in major cities throughout the United States. Contraception. 2018;97:264-269.

13. Wilkinson TA, Clark P, Rafie S, et al. Access to emergency contraception after removal of age restrictions. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20164262.

14. Cleland K, Bass J, Doci F, et al. Access to emergency contraception in the over-the-counter era. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:622-627.

15. Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555-562.

16. McCloskey LR, Wisner KL, Cattan MK, et al. Contraception for women with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:247-255.

17. Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:97-104.

18. Festin MP, Peregoudov A, Seuc A, et al. Effect of BMI and body weight on pregnancy rates with LNG as emergency contraception: analysis of four WHO HRP studies. Contraception. 2017;95:50-54.

19. Edelman AB, Hennebold JD, Bond K, et al. Double dosing levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception for individuals with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):48-54.

20. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FSRH clinical guideline: Emergency contraception. Published March 2017. Amended December 2020. Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/

21. Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ access to contraceptive services. Guttmacher Institute. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

22. Ross NE, Webster TG, Tastenhoye CA, et al. Reproductive decision-making capacity in women with psychiatric illness: a systematic review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63:61-70.

23. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20:30-36.

24. Friedman SH. The ethics of treating depression in pregnancy. J Primary Healthcare. 2015;7:81-83.

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”

Unwanted or mistimed pregnancies account for 45% of all pregnancies.1 While there are ramifications for any unintended pregnancy, the risks for patients with mental illness are greater and include potential adverse effects on the neonate from both psychiatric disease and psychiatric medication use, worse obstetrical outcomes for patients with untreated mental illness, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk in the peripartum period.2 These risks become even more pronounced when psychiatric medications are reflexively discontinued or reduced in pregnancy, which is commonly done contrary to best practice recommendations. In the United States, the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization has erased federal protections for abortion previously conferred by Roe v Wade. As a result, as of early October 2022, abortion had been made illegal in 11 states, and was likely to be banned in many others, most commonly in states where there is limited support for either parents or children. Thus, preventing unplanned pregnancies should be a treatment consideration for all medical disciplines.3

Psychiatrists may hesitate to prescribe emergency contraception (EC) due to fears it falls outside the scope of their practice. However, psychiatry has already moved towards prescribing nonpsychiatric medications when doing so clearly benefits the patient. One example is prescribing metformin to address metabolic syndrome related to the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Emergency contraceptives have strong safety profiles and are easy to prescribe. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to increasing access to emergency contraceptives for psychiatric patients.4 These include the erroneous belief that laboratory and physical exams are needed before starting EC, cost and/or limited stock of emergency contraceptives at pharmacies, and general confusion regarding what constitutes EC vs an oral abortive (Table 15-10). Psychiatrists are particularly well-positioned to support the reproductive autonomy and well-being of patients who struggle to engage with other clinicians. This article aims to help psychiatrists better understand EC so they can comfortably prescribe it before their patients need it.

What is emergency contraception?

EC is medications or devices that patients can use after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy. They do not impede the development of an established pregnancy and thus are not abortifacients. EC is not recommended as a primary means of contraception,9 but it can be extremely valuable to reduce pregnancy risk after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failures such as broken condoms or missed doses of birth control pills. EC can prevent ≥95% of pregnancies when taken within 5 days of at-risk intercourse.11

Methods of EC fall into 2 categories: oral medications (sometimes referred to as “morning after pills”) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). IUDs are the most effective means of EC, especially for patients with higher BMIs or who may be taking medications such as cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 inducers that could interfere with the effectiveness of oral methods. IUDs also have the advantage of providing highly effective ongoing contraception.6 However, IUDs require in-office placement by a trained clinician, and patients may experience difficulty obtaining placement within 5 days of unprotected sex. Therefore, oral medication is the most common form of EC.

Oral EC is safe and effective, and professional societies (including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 and the American Academy of Pediatrics7) recommend routinely prescribing oral EC for patients in advance of need. Advance prescribing eliminates barriers to accessing EC, increases the use of EC, and does not encourage risky sexual behaviors.10

Overview of oral emergency contraception

Two medications are FDA-approved for use as oral EC: ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Both are available in generic and branded versions. While many common birth control pills can also be safely used off-label as emergency contraception (an approach known as the Yuzpe method), they are less effective, not as well-tolerated, and require knowledge of the specific type of pill the patient has available.9 Oral EC appears to work primarily through delay or inhibition of ovulation, and is unlikely to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg.9

Continue to: Ulipristal acetate

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is an oral progesterone receptor agonist-antagonist taken as a single 30 mg dose up to 5 days after unprotected sex. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by UPA use range from 0% to 1.8%.4 Many pharmacies stock UPA, and others (especially chain pharmacies) report being able to order and fill it within 24 hours.12

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is an oral progestin that is available by prescription and has also been approved for over-the-counter sale to patients of all ages and sexes (without the need to show identification) since 2013.8 It is administered as a single 1.5 mg dose taken as soon as possible up to 3 days after unprotected sex, although it may continue to provide benefits when taken within 5 days. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by LNG use range from 0.3% to 2.6%, with much higher odds among women who are obese.4 LNG is available both by prescription or over-the-counter,13 although it is often kept in a locked cabinet or behind the counter, and staff are often misinformed regarding the lack of age restrictions for sale without a prescription.14

Safety and adverse effects. According to the CDC, there are no conditions for which the risks outweigh the advantages of use of either UPA or LNG,5 and patients for whom hormonal birth control is otherwise contraindicated can still use them safely. If a pregnancy has already occurred, taking EC will not harm the developing fetus; it is also safe to use when breastfeeding.5 Both medications are generally well-tolerated—neither has been causally linked to deaths or serious complications,5 and the most common adverse effects are headache (approximately 19%) and nausea (approximately 12%), in addition to irregular bleeding, fatigue, dizziness, and abdominal pain.15 Oral EC may be used more than once, even within the same menstrual cycle. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be encouraged to discuss more efficacious contraceptive options with their primary physician or gynecologist.

Will oral EC affect psychiatric treatment?

Oral EC is unlikely to have a meaningful effect on psychiatric symptoms or management, particularly when compared to the significant impacts of unintended pregnancies. Neither medication is known to have any clinically significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medications, although the effectiveness of both medications can be impaired by CYP3A4 inducers such as carbamazepine.5 In addition, while research has not specifically examined the impact of EC on psychiatric symptoms, the broader literature on hormonal contraception indicates that most patients with psychiatric disorders generally report similar or lower rates of mood symptoms associated with their use.16 Some women treated with hormonal contraceptives do develop dysphoric mood,16 but any such effects resulting from LNG would likely be transient. Mood disruptions or other psychiatric symptoms have not been associated with UPA use.

How to prescribe oral emergency contraception

Who and when. Women of reproductive age should be counseled about EC as part of anticipatory guidance, regardless of their current intentions for sexual behaviors. Patients do not need a physical examination or pregnancy test before being prescribed or using oral EC.9 Much like how intranasal naloxone is prescribed, prescriptions should be provided in advance of need, with multiple refills to facilitate ready access when needed.

Continue to: Which to prescribe

Which to prescribe. UPA is more effective in preventing pregnancy than LNG at all time points up to 120 hours after sex, including for women who are overweight or obese.15 As such, it is recommended as the first-line choice. However, because LNG is available without prescription and is more readily available (including via online order), it may be a good choice for patients who need rapid EC or who prefer a medication that does not require a prescription (Table 24,5,8,9,15).

What to tell patients. Patients should be instructed to fill their prescription before they expect to use it, to ensure ready availability when desired (Table 35,9). Oral EC is shelf stable for at least 3 years when stored in a cool, dry environment. Patients should take the medication as soon as possible following at-risk sexual intercourse (Table 4). Tell them that if they vomit within 3 hours of taking the medication, they should take a second dose. Remind patients that EC does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, or from sex that occurs after the medication is taken (in fact, they can increase the possibility of pregnancy later in that menstrual cycle due to delayed ovulation).9 Counsel patients to abstain from sex or to use barrier contraception for 7 days after use. Those who take birth control pills can resume use immediately after using LNG; they should wait 5 days after taking UPA.

No routine follow-up is needed after taking UPA or LNG. However, patients should get a pregnancy test if their period does not start within 3 weeks, and should seek medical evaluation if they experience significant lower abdominal pain or persistent irregular bleeding in order to rule out pregnancy-related complications. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be recommended to pursue routine contraceptive care.

Billing. Counseling your patients about contraception can increase the reimbursement you receive by adding to the complexity of the encounter (regardless of whether you prescribe a medication) through use of the ICD-10 code Z30.0.

Emergency contraception for special populations

Some patients face additional challenges to effective EC that should be considered when counseling and prescribing. Table 54,5,7,15,17-21 discusses the use of EC in these special populations. Of particular importance for psychiatrists, LNG is less effective at preventing undesired pregnancy among patients who are overweight or obese,15,17,18 and strong CYP3A4-inducing agents may decrease the effectiveness of both LNG and UPA.5 Keep in mind, however, that the advantages of using either UPA or LNG outweigh the risks for all populations.5 Patients must be aware of appropriate information in order to make informed decisions, but should not be discouraged from using EC.

Continue to: Other groups of patients...

Other groups of patients may face barriers due to some clinicians’ hesitancy regarding their ability to consent to reproductive care. Most patients with psychiatric illnesses have decision-making capacity regarding reproductive issues.22 Although EC is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics,7 patients age <18 have varying rights to consent across states,21 and merit special consideration.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. A does not wish to get pregnant at this time, and expresses fears that her recent contraceptive failure could lead to an unintended pregnancy. In addition to her psychiatric treatment, her psychiatrist should discuss EC options with her. She has a healthy BMI and had inadequately protected sex <1 day ago, so her clinician may prescribe LNG (to ensure rapid access for immediate use) in addition to UPA for her to have available in case of future “scares.” The psychiatrist should consider pharmacologic treatment with an antidepressant with a relatively safe reproductive record (eg, sertraline).23 This is considered preventive ethics, since Ms. A is of reproductive age, even if she is not presently planning to get pregnant, due to the aforementioned high rate of unplanned pregnancy.23,24 It is also important for the psychiatrist to continue the dialogue in future sessions about preventing unintended pregnancy. Since Ms. A has benefited from a psychotropic medication when not pregnant, it will be important to discuss with her the risks and benefits of medication should she plan a pregnancy.

Bottom Line

Patients with mental illnesses are at increased risk of adverse outcomes resulting from unintended pregnancies. Clinicians should counsel patients about emergency contraception (EC) as a part of routine psychiatric care, and should prescribe oral EC in advance of patient need to facilitate effective use.

Related Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on Emergency Contraception. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/ articles/2015/09/emergency-contraception

- State policies on emergency contraception. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/emergency-contraception

- State policies on minors’ access to contraceptive services. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

- Patient-oriented contraceptive education materials (in English and Spanish). https://shop.powertodecide.org/ptd-category/educational-materials

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Levonorgestrel • Plan B One-Step, Fallback

Metformin • Glucophage

Naloxone • Narcan

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

Ulipristal acetate • Ella

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Ms. A, age 22, is a college student who presents for an initial psychiatric evaluation. Her body mass index (BMI) is 20 (normal range: 18.5 to 24.9), and her medical history is positive only for childhood asthma. She has been treated for major depressive disorder with venlafaxine by her previous psychiatrist. While this antidepressant has been effective for some symptoms, she has experienced adverse effects and is interested in a different medication. During the evaluation, Ms. A remarks that she had a “scare” last night when the condom broke while having sex with her boyfriend. She says that she is interested in having children at some point, but not at present; she is concerned that getting pregnant now would cause her depression to “spiral out of control.”

Unwanted or mistimed pregnancies account for 45% of all pregnancies.1 While there are ramifications for any unintended pregnancy, the risks for patients with mental illness are greater and include potential adverse effects on the neonate from both psychiatric disease and psychiatric medication use, worse obstetrical outcomes for patients with untreated mental illness, and worsening of psychiatric symptoms and suicide risk in the peripartum period.2 These risks become even more pronounced when psychiatric medications are reflexively discontinued or reduced in pregnancy, which is commonly done contrary to best practice recommendations. In the United States, the recent Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v Jackson Women’s Health Organization has erased federal protections for abortion previously conferred by Roe v Wade. As a result, as of early October 2022, abortion had been made illegal in 11 states, and was likely to be banned in many others, most commonly in states where there is limited support for either parents or children. Thus, preventing unplanned pregnancies should be a treatment consideration for all medical disciplines.3

Psychiatrists may hesitate to prescribe emergency contraception (EC) due to fears it falls outside the scope of their practice. However, psychiatry has already moved towards prescribing nonpsychiatric medications when doing so clearly benefits the patient. One example is prescribing metformin to address metabolic syndrome related to the use of second-generation antipsychotics. Emergency contraceptives have strong safety profiles and are easy to prescribe. Unfortunately, there are many barriers to increasing access to emergency contraceptives for psychiatric patients.4 These include the erroneous belief that laboratory and physical exams are needed before starting EC, cost and/or limited stock of emergency contraceptives at pharmacies, and general confusion regarding what constitutes EC vs an oral abortive (Table 15-10). Psychiatrists are particularly well-positioned to support the reproductive autonomy and well-being of patients who struggle to engage with other clinicians. This article aims to help psychiatrists better understand EC so they can comfortably prescribe it before their patients need it.

What is emergency contraception?

EC is medications or devices that patients can use after sexual intercourse to prevent pregnancy. They do not impede the development of an established pregnancy and thus are not abortifacients. EC is not recommended as a primary means of contraception,9 but it can be extremely valuable to reduce pregnancy risk after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failures such as broken condoms or missed doses of birth control pills. EC can prevent ≥95% of pregnancies when taken within 5 days of at-risk intercourse.11

Methods of EC fall into 2 categories: oral medications (sometimes referred to as “morning after pills”) and intrauterine devices (IUDs). IUDs are the most effective means of EC, especially for patients with higher BMIs or who may be taking medications such as cytochrome P450 (CYP)3A4 inducers that could interfere with the effectiveness of oral methods. IUDs also have the advantage of providing highly effective ongoing contraception.6 However, IUDs require in-office placement by a trained clinician, and patients may experience difficulty obtaining placement within 5 days of unprotected sex. Therefore, oral medication is the most common form of EC.

Oral EC is safe and effective, and professional societies (including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 and the American Academy of Pediatrics7) recommend routinely prescribing oral EC for patients in advance of need. Advance prescribing eliminates barriers to accessing EC, increases the use of EC, and does not encourage risky sexual behaviors.10

Overview of oral emergency contraception

Two medications are FDA-approved for use as oral EC: ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Both are available in generic and branded versions. While many common birth control pills can also be safely used off-label as emergency contraception (an approach known as the Yuzpe method), they are less effective, not as well-tolerated, and require knowledge of the specific type of pill the patient has available.9 Oral EC appears to work primarily through delay or inhibition of ovulation, and is unlikely to prevent implantation of a fertilized egg.9

Continue to: Ulipristal acetate

Ulipristal acetate (UPA) is an oral progesterone receptor agonist-antagonist taken as a single 30 mg dose up to 5 days after unprotected sex. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by UPA use range from 0% to 1.8%.4 Many pharmacies stock UPA, and others (especially chain pharmacies) report being able to order and fill it within 24 hours.12

Levonorgestrel (LNG) is an oral progestin that is available by prescription and has also been approved for over-the-counter sale to patients of all ages and sexes (without the need to show identification) since 2013.8 It is administered as a single 1.5 mg dose taken as soon as possible up to 3 days after unprotected sex, although it may continue to provide benefits when taken within 5 days. Pregnancy rates from a single act of unprotected sex followed by LNG use range from 0.3% to 2.6%, with much higher odds among women who are obese.4 LNG is available both by prescription or over-the-counter,13 although it is often kept in a locked cabinet or behind the counter, and staff are often misinformed regarding the lack of age restrictions for sale without a prescription.14

Safety and adverse effects. According to the CDC, there are no conditions for which the risks outweigh the advantages of use of either UPA or LNG,5 and patients for whom hormonal birth control is otherwise contraindicated can still use them safely. If a pregnancy has already occurred, taking EC will not harm the developing fetus; it is also safe to use when breastfeeding.5 Both medications are generally well-tolerated—neither has been causally linked to deaths or serious complications,5 and the most common adverse effects are headache (approximately 19%) and nausea (approximately 12%), in addition to irregular bleeding, fatigue, dizziness, and abdominal pain.15 Oral EC may be used more than once, even within the same menstrual cycle. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be encouraged to discuss more efficacious contraceptive options with their primary physician or gynecologist.

Will oral EC affect psychiatric treatment?

Oral EC is unlikely to have a meaningful effect on psychiatric symptoms or management, particularly when compared to the significant impacts of unintended pregnancies. Neither medication is known to have any clinically significant impacts on the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of psychotropic medications, although the effectiveness of both medications can be impaired by CYP3A4 inducers such as carbamazepine.5 In addition, while research has not specifically examined the impact of EC on psychiatric symptoms, the broader literature on hormonal contraception indicates that most patients with psychiatric disorders generally report similar or lower rates of mood symptoms associated with their use.16 Some women treated with hormonal contraceptives do develop dysphoric mood,16 but any such effects resulting from LNG would likely be transient. Mood disruptions or other psychiatric symptoms have not been associated with UPA use.

How to prescribe oral emergency contraception

Who and when. Women of reproductive age should be counseled about EC as part of anticipatory guidance, regardless of their current intentions for sexual behaviors. Patients do not need a physical examination or pregnancy test before being prescribed or using oral EC.9 Much like how intranasal naloxone is prescribed, prescriptions should be provided in advance of need, with multiple refills to facilitate ready access when needed.

Continue to: Which to prescribe

Which to prescribe. UPA is more effective in preventing pregnancy than LNG at all time points up to 120 hours after sex, including for women who are overweight or obese.15 As such, it is recommended as the first-line choice. However, because LNG is available without prescription and is more readily available (including via online order), it may be a good choice for patients who need rapid EC or who prefer a medication that does not require a prescription (Table 24,5,8,9,15).

What to tell patients. Patients should be instructed to fill their prescription before they expect to use it, to ensure ready availability when desired (Table 35,9). Oral EC is shelf stable for at least 3 years when stored in a cool, dry environment. Patients should take the medication as soon as possible following at-risk sexual intercourse (Table 4). Tell them that if they vomit within 3 hours of taking the medication, they should take a second dose. Remind patients that EC does not protect against sexually transmitted infections, or from sex that occurs after the medication is taken (in fact, they can increase the possibility of pregnancy later in that menstrual cycle due to delayed ovulation).9 Counsel patients to abstain from sex or to use barrier contraception for 7 days after use. Those who take birth control pills can resume use immediately after using LNG; they should wait 5 days after taking UPA.

No routine follow-up is needed after taking UPA or LNG. However, patients should get a pregnancy test if their period does not start within 3 weeks, and should seek medical evaluation if they experience significant lower abdominal pain or persistent irregular bleeding in order to rule out pregnancy-related complications. Patients who use EC repeatedly should be recommended to pursue routine contraceptive care.

Billing. Counseling your patients about contraception can increase the reimbursement you receive by adding to the complexity of the encounter (regardless of whether you prescribe a medication) through use of the ICD-10 code Z30.0.

Emergency contraception for special populations

Some patients face additional challenges to effective EC that should be considered when counseling and prescribing. Table 54,5,7,15,17-21 discusses the use of EC in these special populations. Of particular importance for psychiatrists, LNG is less effective at preventing undesired pregnancy among patients who are overweight or obese,15,17,18 and strong CYP3A4-inducing agents may decrease the effectiveness of both LNG and UPA.5 Keep in mind, however, that the advantages of using either UPA or LNG outweigh the risks for all populations.5 Patients must be aware of appropriate information in order to make informed decisions, but should not be discouraged from using EC.

Continue to: Other groups of patients...

Other groups of patients may face barriers due to some clinicians’ hesitancy regarding their ability to consent to reproductive care. Most patients with psychiatric illnesses have decision-making capacity regarding reproductive issues.22 Although EC is supported by the American Academy of Pediatrics,7 patients age <18 have varying rights to consent across states,21 and merit special consideration.

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. A does not wish to get pregnant at this time, and expresses fears that her recent contraceptive failure could lead to an unintended pregnancy. In addition to her psychiatric treatment, her psychiatrist should discuss EC options with her. She has a healthy BMI and had inadequately protected sex <1 day ago, so her clinician may prescribe LNG (to ensure rapid access for immediate use) in addition to UPA for her to have available in case of future “scares.” The psychiatrist should consider pharmacologic treatment with an antidepressant with a relatively safe reproductive record (eg, sertraline).23 This is considered preventive ethics, since Ms. A is of reproductive age, even if she is not presently planning to get pregnant, due to the aforementioned high rate of unplanned pregnancy.23,24 It is also important for the psychiatrist to continue the dialogue in future sessions about preventing unintended pregnancy. Since Ms. A has benefited from a psychotropic medication when not pregnant, it will be important to discuss with her the risks and benefits of medication should she plan a pregnancy.

Bottom Line

Patients with mental illnesses are at increased risk of adverse outcomes resulting from unintended pregnancies. Clinicians should counsel patients about emergency contraception (EC) as a part of routine psychiatric care, and should prescribe oral EC in advance of patient need to facilitate effective use.

Related Resources

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Practice Bulletin on Emergency Contraception. https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-bulletin/ articles/2015/09/emergency-contraception

- State policies on emergency contraception. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/emergency-contraception

- State policies on minors’ access to contraceptive services. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

- Patient-oriented contraceptive education materials (in English and Spanish). https://shop.powertodecide.org/ptd-category/educational-materials

Drug Brand Names

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Levonorgestrel • Plan B One-Step, Fallback

Metformin • Glucophage

Naloxone • Narcan

Norethindrone • Aygestin

Sertraline • Zoloft

Topiramate • Topamax

Ulipristal acetate • Ella

Venlafaxine • Effexor

1. Grossman D. Expanding access to short-acting hormonal contraceptive methods in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1209-1210.

2. Gur TL, Kim DR, Epperson CN. Central nervous system effects of prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: sensing the signal through the noise. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227:567-582.

3. Ross N, Landess J, Kaempf A, et al. Pregnancy termination: what psychiatrists need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21:8-9.

4. Haeger KO, Lamme J, Cleland K. State of emergency contraception in the US, 2018. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:20.

5. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-3.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 707: Access to emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e48-e52.

7. Upadhya KK, Breuner CC, Alderman EM, et al. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193149.

8. Rowan A. Obama administration yields to the courts and the evidence, allows emergency contraception to be sold without restrictions. Guttmacher Institute. Published June 25, 2013. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/obama-administration-yields-courts-and-evidence-allows-emergency-contraception-be-sold#

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e1-e11.

10. Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, Gaffield ML, et al. Advance supply of emergency contraception: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:590-601.

11. World Health Organization. Emergency contraception. Published November 9, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/emergency-contraception

12. Shigesato M, Elia J, Tschann M, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in major cities throughout the United States. Contraception. 2018;97:264-269.

13. Wilkinson TA, Clark P, Rafie S, et al. Access to emergency contraception after removal of age restrictions. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20164262.

14. Cleland K, Bass J, Doci F, et al. Access to emergency contraception in the over-the-counter era. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:622-627.

15. Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555-562.

16. McCloskey LR, Wisner KL, Cattan MK, et al. Contraception for women with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:247-255.

17. Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:97-104.

18. Festin MP, Peregoudov A, Seuc A, et al. Effect of BMI and body weight on pregnancy rates with LNG as emergency contraception: analysis of four WHO HRP studies. Contraception. 2017;95:50-54.

19. Edelman AB, Hennebold JD, Bond K, et al. Double dosing levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception for individuals with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):48-54.

20. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FSRH clinical guideline: Emergency contraception. Published March 2017. Amended December 2020. Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/

21. Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ access to contraceptive services. Guttmacher Institute. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

22. Ross NE, Webster TG, Tastenhoye CA, et al. Reproductive decision-making capacity in women with psychiatric illness: a systematic review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63:61-70.

23. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20:30-36.

24. Friedman SH. The ethics of treating depression in pregnancy. J Primary Healthcare. 2015;7:81-83.

1. Grossman D. Expanding access to short-acting hormonal contraceptive methods in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1209-1210.

2. Gur TL, Kim DR, Epperson CN. Central nervous system effects of prenatal selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: sensing the signal through the noise. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;227:567-582.

3. Ross N, Landess J, Kaempf A, et al. Pregnancy termination: what psychiatrists need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21:8-9.

4. Haeger KO, Lamme J, Cleland K. State of emergency contraception in the US, 2018. Contracept Reprod Med. 2018;3:20.

5. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65:1-3.

6. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No 707: Access to emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:e48-e52.

7. Upadhya KK, Breuner CC, Alderman EM, et al. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2019;144:e20193149.

8. Rowan A. Obama administration yields to the courts and the evidence, allows emergency contraception to be sold without restrictions. Guttmacher Institute. Published June 25, 2013. Accessed July 31, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/gpr/2013/06/obama-administration-yields-courts-and-evidence-allows-emergency-contraception-be-sold#

9. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 152: Emergency contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:e1-e11.

10. Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, Gaffield ML, et al. Advance supply of emergency contraception: a systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:590-601.

11. World Health Organization. Emergency contraception. Published November 9, 2021. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/emergency-contraception

12. Shigesato M, Elia J, Tschann M, et al. Pharmacy access to ulipristal acetate in major cities throughout the United States. Contraception. 2018;97:264-269.

13. Wilkinson TA, Clark P, Rafie S, et al. Access to emergency contraception after removal of age restrictions. Pediatrics. 2017;140:e20164262.

14. Cleland K, Bass J, Doci F, et al. Access to emergency contraception in the over-the-counter era. Women’s Health Issues. 2016;26:622-627.

15. Glasier AF, Cameron ST, Fine PM, et al. Ulipristal acetate versus levonorgestrel for emergency contraception: a randomised non-inferiority trial and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:555-562.

16. McCloskey LR, Wisner KL, Cattan MK, et al. Contraception for women with psychiatric disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2021;178:247-255.

17. Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathé H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91:97-104.

18. Festin MP, Peregoudov A, Seuc A, et al. Effect of BMI and body weight on pregnancy rates with LNG as emergency contraception: analysis of four WHO HRP studies. Contraception. 2017;95:50-54.

19. Edelman AB, Hennebold JD, Bond K, et al. Double dosing levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception for individuals with obesity: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):48-54.

20. FSRH Clinical Effectiveness Unit. FSRH clinical guideline: Emergency contraception. Published March 2017. Amended December 2020. Faculty of Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.fsrh.org/documents/ceu-clinical-guidance-emergency-contraception-march-2017/

21. Guttmacher Institute. Minors’ access to contraceptive services. Guttmacher Institute. Accessed August 4, 2022. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/minors-access-contraceptive-services

22. Ross NE, Webster TG, Tastenhoye CA, et al. Reproductive decision-making capacity in women with psychiatric illness: a systematic review. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2022;63:61-70.

23. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20:30-36.

24. Friedman SH. The ethics of treating depression in pregnancy. J Primary Healthcare. 2015;7:81-83.