User login

Managing diabetes is a complex undertaking, with an extensive regimen of self-care—including regular exercise, meal planning, blood glucose monitoring, medication scheduling, and multiple visits—that is critically linked to glycemic control and the prevention of complications. Incorporating all of these elements into daily life can be daunting.1-3

In fact, nearly half of US adults with diabetes fail to meet the recommended targets.4 This leads to frustration, which often manifests in psychosocial problems that further hamper efforts to manage the disease.5-10 The most notable is a psychosocial disorder known as diabetes distress, which affects close to 45% of those with diabetes.11,12

It is important to note that diabetes distress is not a psychiatric disorder;13 rather, it is a broad affective reaction to the stress of living with this chronic and complex disease.14,15 By negatively affecting adherence to a self-care regimen, diabetes distress contributes to worsening glycemic control and increasing morbidity.16-18

Recognizing that about 80% of those with diabetes are treated in primary care settings,19 we wrote this review to call your attention to diabetes distress, alert you to brief screening tools that can easily be incorporated into clinic visits, and offer guidance in matching proposed interventions to the aspects of diabetes self-management that cause patients the greatest distress.

Diabetes distress: What it is, what it’s not

For patients with type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress centers around 4 main issues:

- frustration with the demands of self-care;

- apprehension about the future and the possibility of developing serious complications;

- concern about both the quality and the cost of required medical care; and

- perceived lack of support from family and/or friends.11,12,20

As mentioned earlier, diabetes distress is not a psychiatric condition and should not be confused with major depressive disorder (MDD). Here’s help in telling the difference.

For starters, a diagnosis of depression is symptom-based.13 MDD requires the presence of at least 5 of the 9 symptoms defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. (DSM-5)—eg, persistent feelings of worthlessness or guilt, sleep disturbances, lack of interest in normal activities—for at least 2 weeks.21 What’s more, the diagnostic criteria for MDD do not specify a cause or disease process. Nor do they distinguish between a pathological response and an expected reaction to a stressful life event.22 Further, depression measures reflect symptoms (eg, hyperglycemia), as well as stressful experiences resulting from diabetes self-care, which may contribute to the high rate of false positives or incorrect diagnoses of MDD and missed diagnoses of diabetes distress.23

Unlike MDD, diabetes distress has a specific cause—diabetes—and can best be understood as an emotional response to a demanding health condition.13 And, because the source of the problem is identified, diabetes distress can be treated with specific interventions targeting the areas causing the highest levels of stress.

When a psychiatric condition and diabetes distress overlap

MDD, anxiety disorders, and diabetes distress are all common in patients with diabetes,24 and the co-occurrence of a psychiatric disorder and diabetes distress is high.25 Thus, it is important not only to identify cases of diabetes distress but also to consider comorbid depression and/or anxiety in patients with diabetes distress.

More often, though, it is the other way around, according to the Distress and Depression in Diabetes (3D) study. The researchers recently found that 84% of patients with moderate or high diabetes distress did not fulfill the criteria for MDD, but that 67% of diabetes patients with MDD also had moderate or high diabetes distress.13,15,17,25

The data highlight the importance of screening patients with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and MDD for diabetes distress. Keep in mind that individuals diagnosed with both diabetes distress and a comorbid psychiatric condition may require more complex and intensive treatment than those with either diabetes distress or MDD alone.25

Screening for diabetes distress

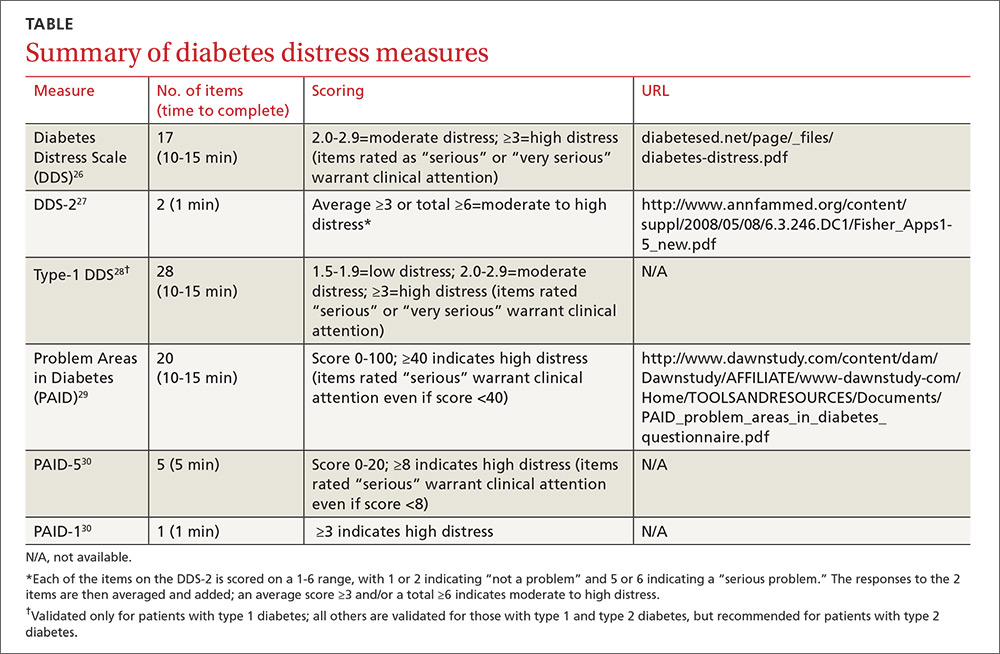

Diabetes distress can be easily assessed using one of several patient-reported outcome measures. Six validated measures, ranging in length from one to 28 questions, are designed for use in primary care (TABLE).26-30 Some of the measures are easily accessible online; others require subscription to MEDLINE.

Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID): There are 3 versions of PAID—a 20-item screen assessing a broad range of feelings related to living with diabetes and its treatment, a 5-item version (PAID-5) with high rates of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (89%), and a single-item test (PAID-1) that is highly correlated with the longer version.26,27

Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS): This tool is available in a 17-item measure assessing diabetes distress as it relates to the emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress, and interpersonal distress.28 DDS is also available in a short form (DDS-2) with 2 items29 and a 28-item scale specifically for patients with type 1 diabetes.30 T1-DDS, the only diabetes distress measure focused on this particular patient population, assesses the 7 sources of distress found to be common among adults with type 1 diabetes: powerlessness, negative social perceptions, physician distress, friend/family distress, hypoglycemia distress, management distress, and eating distress.

Studies have shown that not only do those with type 1 diabetes experience different stressors compared with their type 2 counterparts, but that they tend to experience distress differently. For patients with type 1 diabetes, for example, powerlessness ranked as the highest source of distress, followed by eating distress and hypoglycemia distress. These sources of distress differ from the regimen distress, emotional burden, interpersonal distress, and physician distress identified by those with type 2 diabetes.30

How to respond to diabetes distress

Diabetes distress is easier to identify than to successfully treat. Few validated treatments for diabetes distress exist and, to our knowledge, only 2 studies have assessed interventions aimed at reduction of such distress.31,32

The REDEEM trial31 recruited adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetes distress to participate in a 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT). The trial had 3 arms, comparing the effectiveness of a computer-assisted self-management (CASM) program alone, a CASM program plus in-person diabetes distress-specific problem-solving therapy, and a computer-assisted minimally supportive intervention. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (using the DDS scale and subscales), along with self-management behaviors and HbA1c.

Participants in all 3 arms showed significant reductions in total diabetes distress and improvements in self-management behaviors, with no significant differences among the groups. No differences in HbA1c were found. However, those in the CASM program plus distress-specific therapy arm showed a larger reduction in regimen distress compared with the other 2 groups.31

The DIAMOS trial32 recruited adults who had type 1 or type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress, and subclinical depressive symptoms for a 2-arm RCT. One group underwent cognitive behavioral interventions, while the controls had standard group-based diabetes education. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (measured via the PAID scale), depressive symptoms, well-being, diabetes self-care, diabetes acceptance, satisfaction with diabetes treatment, HbA1c, and subclinical inflammation.

The intervention group showed greater improvement in diabetes distress and depressive symptoms compared with the control group, but no differences in well-being, self-care, treatment satisfaction, HbA1c, or subclinical inflammation were observed.32

Both studies support the use of problem-solving therapy and cognitive behavioral interventions for patients with diabetes distress. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in the primary care setting.

What else to offer when challenges mount?

Diabetes is a progressive disease, and most patients experience multiple challenges over time. These typically include complications and comorbidities, physical limitations, polypharmacy, hypoglycemia, and cognitive impairment, as well as changes in everything from medication and lifestyle to insurance coverage and social support.33,34 All increase the risk for diabetes distress, as well as related psychiatric conditions.

Aging and diabetes are independent risk factors for cognitive impairment, for example, and the presence of both increases this risk.35 What’s more, diabetes alone is associated with poorer executive function,36-38 the higher-level cognitive processes that allow individuals to engage in independent, purposeful, and flexible goal-related behaviors. Both poor cognitive function and impaired executive function interfere with the ability to perform self-care behaviors such as adjusting insulin doses, drawing insulin into a syringe, or dialing an insulin dose with an insulin pen.39 This in turn can lead to frustration and increase the likelihood of moderate to high diabetes distress.

Assessing diabetes distress in patients with cognitive impairment, poor executive functioning, or other psychological limitations is particularly difficult, however, as no diabetes distress measures take such deficits into account. Thus, primary care physicians without expertise in neuropsychology should consider referring patients with such problems to specialists for assessment.

The progressive nature of diabetes also highlights the need for primary care physicians to periodically screen for diabetes distress and engage in ongoing discussions about what type of care is best for individual patients, and why. When developing or updating treatment plans and making recommendations, it is crucial to consider the impact the treatment would likely have on the patient’s physical and mental health and to explicitly inquire about and acknowledge his or her values and preferences for care.40-44

It is also important to remain aware of socioeconomic changes—in employment, insurance coverage, and living situations, for example—which are not addressed in the screening tools.

Moderate to high diabetes distress scores, as well as individual items patients identify as “very serious” problems, represent clinical red flags that should be the focus of careful discussion during a medical visit. Patients with moderate to high distress should be referred to a therapist trained in cognitive behavioral therapy or problem-solving therapy. Physicians who lack access to such resources can incorporate cognitive behavioral and problem-solving techniques into patient discussion. (See “Directing help where it’s most needed.”) All patients should be referred to a certified diabetes educator—a key component of diabetes care.45,46

SIDEBAR

Directing help where it's most needed

CASE 1 ›

Conduct a behavioral experiment

Fred J, a 67-year-old diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 6 years ago, comes in for a diabetes check-up. He is a new patient who recently retired from his job as a contractor and was referred by a colleague. In response to a question about his diabetes management, Mr. J tells you he’s having a hard time.

“I get down on myself,” the patient says. “I take my medications every day at the exact same time, but when I test my sugar, it’s 260 or 280. I know I did this to myself. If only I weighed less, ate better, or exercised more.”

At other times, “I think, 'Why bother?'” Mr. J adds. “I feel like there’s nothing I can do to make it better.”

The DDS-2 screen you gave Mr. J bears out his high level of distress and his fear of complications. He tells you about an aunt who “had diabetes like me and had to go on dialysis, then died 2 years later.” When you ask what he fears most, Mr. J says he worries about kidney failure. “I don’t want to go on dialysis,” he insists.

You take the opportunity to point out that nephropathy is not inevitable and that he can perform self-care behaviors now that will prevent or delay kidney complications.

You also decide to try a cognitive behavioral technique in an attempt to change his thought process. You ask Mr. J to agree to a week-long behavioral experiment to examine the effect of walking for 30 minutes each day.

He agrees. You advise him to write down his predictions before he begins the experiment and then to keep a log, checking and recording his glucose levels before and after each walk. You schedule a follow-up visit to discuss the results, hoping that a reduction in blood glucose levels will convince Mr. J that exercise is beneficial to his diabetes.

CASE 2 ›

Identify the problem; brainstorm with the patient

Susan T, a 46-year-old with a husband and 2 teenage children, comes in for her 3-month diabetes check-up. At her last visit, she expressed concerns about her family’s lack of cooperation as she struggled to change her diet. This time, she appears frustrated and distraught.

Your nurse administered the PAID-5 while Ms. T was in the waiting room and entered her score—8, indicating high diabetes distress—in the electronic medical record. You ask Ms. T what’s happening, knowing that encouraging her to verbalize her feelings is a way to increase her trust and help alleviate her concerns.

You also try the following problem-solving technique:

Define the problem. Ms. T is having a hard time maintaining a healthy diet. Her husband and children refuse to eat the healthy meals she prepares and want her to cook separate dinners for them.

Identify challenges. The patient works full-time and does not have the time or energy to cook separate meals. In addition, she is upset by her family’s lack of support in her efforts to control her disease.

Brainstorm multiple solutions:

1) Ms. T can prepare all of her own meals for the work week on Sunday, then cook for the others when she returns from work.

2) Her husband and children can make their own dinner if they do not want to eat the healthier meals she prepares.

3) The patient can join a diabetes support group where she will meet, and possibly learn from, other patients who may be struggling with diabetes self-care.

4) Ms. T can ask her husband and children to come to her next diabetes check-up so they can learn about the importance of family support in diabetes management directly from you.

5) The patient’s family can receive information about a healthy diabetes diet from a certified diabetes educator.

Decide on appropriate solutions. The patient agrees to try and prepare her weekday meals on Sunday so that she is not tempted to eat less healthy options. She also agrees to bring her family to her next diabetes check-up and to diabetes education classes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, 35 W. Green Drive, Athens, OH 45701; beverle1@ohio.edu.

1. Gafarian CT, Heiby EM, Blair P, et al. The diabetes time management questionnaire. Diabetes Educator. 1999;25:585-592.

2. Wdowik MJ, Kendall PA, Harris MA. College students with diabetes: using focus groups and interviews to determine psychosocial issues and barriers to control. Diabetes Educator. 1997;23:558-562.

3. Rubin RR. Psychological issues and treatment for people with diabetes. J Clin Psych. 2001;57:457-478.

4. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999-2010. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:287-288.

5. Lloyd CE, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: Review of the links. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18:121-127.

6. Weinger K. Psychosocial issues and self-care. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(6 suppl): S34-S38.

7. Weinger K, Jacobson AM. Psychosocial and quality of life correlates of glycemic control during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Education Counseling. 2001;42:123-131.

8. Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: an RRNeST study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354-360.

9. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2222-2227.

10. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1102-1107.

11. Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RI, et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2013;30:767-777.

12. Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky W, et al. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful?: establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:259-264.

13. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

14. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, et al. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetic Med. 2009;26:622-627.

15. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:542-548.

16. Gonzalez JS, Delahanty LM, Safren SA, et al. Differentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2822-1825.

17. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, et al. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:23-28.

18. Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, Devellis BM, et al. Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: a systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33:1080-1103; 1104-1086.

19. Peterson KA, Radosevich DM, O’Connor PJ, et al. Improving diabetes care in practice: findings from the TRANSLATE trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2238-2243.

20. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA. The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1034-1036.

21. Cole J, McGuffin P, Farmer AE. The classification of depression: are we still confused? Br J Psychiatr. 2008;192:83-85.

22. Wakefield JC. The concept of mental disorder. On the boundary between biological facts and social values. Am Psychologist. 1992;47:373-388.

23. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

24. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278-3285.

25. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. A longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1096-1101.

26. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754-760.

27. McGuire BE, Morrison TG, Hermanns N, et al. Short-form measures of diabetes-related emotional distress: the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID)-5 and PAID-1. Diabetologia. 2010;53:66-69.

28. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626-631.

29. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Mullan JT, et al. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:246-252.

30. Fisher L, Polonsky WH, Hessler DM, et al. Understanding the sources of diabetes distress in adults with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:572-577.

31. Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2551-2558.

32. Hermanns N, Schmitt A, Gahr A, et al. The effect of a Diabetes-Specific Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Program (DIAMOS) for patients with diabetes and subclinical depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:551-560.

33. Weinger K, Beverly EA, Smaldone A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. Western J Nurs Res. 2014;36:1272-1298.

34. Beverly EA, Ritholz MD, Shepherd C, et al. The psychosocial challenges and care of older adults with diabetes: “can’t do what I used to do; can’t be who I once was.” Curr Diabetes Rep. 2016;16:48.

35. Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2009;4:e4144.

36. Thabit H, Kyaw TT, McDermott J, et al. Executive function and diabetes mellitus—a stone left unturned? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8:109-115.

37. McNally K, Rohan J, Pendley JS, et al. Executive functioning, treatment adherence, and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1159-1162.

38. Rucker JL, McDowd JM, Kluding PM. Executive function and type 2 diabetes: putting the pieces together. Phys Ther. 2012;92:454-462.

39. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2650-2664.

40. Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006;295:1935-1940.

41. Oftedal B, Karlsen B, Bru E. Life values and self-regulation behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2548-2556.

42. Morrow AS, Haidet P, Skinner J, et al. Integrating diabetes self-management with the health goals of older adults: a qualitative exploration. Patient Education Counseling. 2008;72:418-423.

43. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:306-311.

44. Beverly EA, Wray LA, LaCoe CL, et al. Listening to older adults’ values and preferences for Type 2 diabetes care: a qualitative study. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27:44-49.

45. American Association of Diabetes Educators. Why refer for diabetes education? American Association of Diabetes Educators. Available at: https://www.diabeteseducator.org/practice/provider-resources/why-refer-for-diabetes-education. Accessed August 15, 2016.

46. Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363:1589-1597.

Managing diabetes is a complex undertaking, with an extensive regimen of self-care—including regular exercise, meal planning, blood glucose monitoring, medication scheduling, and multiple visits—that is critically linked to glycemic control and the prevention of complications. Incorporating all of these elements into daily life can be daunting.1-3

In fact, nearly half of US adults with diabetes fail to meet the recommended targets.4 This leads to frustration, which often manifests in psychosocial problems that further hamper efforts to manage the disease.5-10 The most notable is a psychosocial disorder known as diabetes distress, which affects close to 45% of those with diabetes.11,12

It is important to note that diabetes distress is not a psychiatric disorder;13 rather, it is a broad affective reaction to the stress of living with this chronic and complex disease.14,15 By negatively affecting adherence to a self-care regimen, diabetes distress contributes to worsening glycemic control and increasing morbidity.16-18

Recognizing that about 80% of those with diabetes are treated in primary care settings,19 we wrote this review to call your attention to diabetes distress, alert you to brief screening tools that can easily be incorporated into clinic visits, and offer guidance in matching proposed interventions to the aspects of diabetes self-management that cause patients the greatest distress.

Diabetes distress: What it is, what it’s not

For patients with type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress centers around 4 main issues:

- frustration with the demands of self-care;

- apprehension about the future and the possibility of developing serious complications;

- concern about both the quality and the cost of required medical care; and

- perceived lack of support from family and/or friends.11,12,20

As mentioned earlier, diabetes distress is not a psychiatric condition and should not be confused with major depressive disorder (MDD). Here’s help in telling the difference.

For starters, a diagnosis of depression is symptom-based.13 MDD requires the presence of at least 5 of the 9 symptoms defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. (DSM-5)—eg, persistent feelings of worthlessness or guilt, sleep disturbances, lack of interest in normal activities—for at least 2 weeks.21 What’s more, the diagnostic criteria for MDD do not specify a cause or disease process. Nor do they distinguish between a pathological response and an expected reaction to a stressful life event.22 Further, depression measures reflect symptoms (eg, hyperglycemia), as well as stressful experiences resulting from diabetes self-care, which may contribute to the high rate of false positives or incorrect diagnoses of MDD and missed diagnoses of diabetes distress.23

Unlike MDD, diabetes distress has a specific cause—diabetes—and can best be understood as an emotional response to a demanding health condition.13 And, because the source of the problem is identified, diabetes distress can be treated with specific interventions targeting the areas causing the highest levels of stress.

When a psychiatric condition and diabetes distress overlap

MDD, anxiety disorders, and diabetes distress are all common in patients with diabetes,24 and the co-occurrence of a psychiatric disorder and diabetes distress is high.25 Thus, it is important not only to identify cases of diabetes distress but also to consider comorbid depression and/or anxiety in patients with diabetes distress.

More often, though, it is the other way around, according to the Distress and Depression in Diabetes (3D) study. The researchers recently found that 84% of patients with moderate or high diabetes distress did not fulfill the criteria for MDD, but that 67% of diabetes patients with MDD also had moderate or high diabetes distress.13,15,17,25

The data highlight the importance of screening patients with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and MDD for diabetes distress. Keep in mind that individuals diagnosed with both diabetes distress and a comorbid psychiatric condition may require more complex and intensive treatment than those with either diabetes distress or MDD alone.25

Screening for diabetes distress

Diabetes distress can be easily assessed using one of several patient-reported outcome measures. Six validated measures, ranging in length from one to 28 questions, are designed for use in primary care (TABLE).26-30 Some of the measures are easily accessible online; others require subscription to MEDLINE.

Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID): There are 3 versions of PAID—a 20-item screen assessing a broad range of feelings related to living with diabetes and its treatment, a 5-item version (PAID-5) with high rates of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (89%), and a single-item test (PAID-1) that is highly correlated with the longer version.26,27

Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS): This tool is available in a 17-item measure assessing diabetes distress as it relates to the emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress, and interpersonal distress.28 DDS is also available in a short form (DDS-2) with 2 items29 and a 28-item scale specifically for patients with type 1 diabetes.30 T1-DDS, the only diabetes distress measure focused on this particular patient population, assesses the 7 sources of distress found to be common among adults with type 1 diabetes: powerlessness, negative social perceptions, physician distress, friend/family distress, hypoglycemia distress, management distress, and eating distress.

Studies have shown that not only do those with type 1 diabetes experience different stressors compared with their type 2 counterparts, but that they tend to experience distress differently. For patients with type 1 diabetes, for example, powerlessness ranked as the highest source of distress, followed by eating distress and hypoglycemia distress. These sources of distress differ from the regimen distress, emotional burden, interpersonal distress, and physician distress identified by those with type 2 diabetes.30

How to respond to diabetes distress

Diabetes distress is easier to identify than to successfully treat. Few validated treatments for diabetes distress exist and, to our knowledge, only 2 studies have assessed interventions aimed at reduction of such distress.31,32

The REDEEM trial31 recruited adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetes distress to participate in a 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT). The trial had 3 arms, comparing the effectiveness of a computer-assisted self-management (CASM) program alone, a CASM program plus in-person diabetes distress-specific problem-solving therapy, and a computer-assisted minimally supportive intervention. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (using the DDS scale and subscales), along with self-management behaviors and HbA1c.

Participants in all 3 arms showed significant reductions in total diabetes distress and improvements in self-management behaviors, with no significant differences among the groups. No differences in HbA1c were found. However, those in the CASM program plus distress-specific therapy arm showed a larger reduction in regimen distress compared with the other 2 groups.31

The DIAMOS trial32 recruited adults who had type 1 or type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress, and subclinical depressive symptoms for a 2-arm RCT. One group underwent cognitive behavioral interventions, while the controls had standard group-based diabetes education. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (measured via the PAID scale), depressive symptoms, well-being, diabetes self-care, diabetes acceptance, satisfaction with diabetes treatment, HbA1c, and subclinical inflammation.

The intervention group showed greater improvement in diabetes distress and depressive symptoms compared with the control group, but no differences in well-being, self-care, treatment satisfaction, HbA1c, or subclinical inflammation were observed.32

Both studies support the use of problem-solving therapy and cognitive behavioral interventions for patients with diabetes distress. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in the primary care setting.

What else to offer when challenges mount?

Diabetes is a progressive disease, and most patients experience multiple challenges over time. These typically include complications and comorbidities, physical limitations, polypharmacy, hypoglycemia, and cognitive impairment, as well as changes in everything from medication and lifestyle to insurance coverage and social support.33,34 All increase the risk for diabetes distress, as well as related psychiatric conditions.

Aging and diabetes are independent risk factors for cognitive impairment, for example, and the presence of both increases this risk.35 What’s more, diabetes alone is associated with poorer executive function,36-38 the higher-level cognitive processes that allow individuals to engage in independent, purposeful, and flexible goal-related behaviors. Both poor cognitive function and impaired executive function interfere with the ability to perform self-care behaviors such as adjusting insulin doses, drawing insulin into a syringe, or dialing an insulin dose with an insulin pen.39 This in turn can lead to frustration and increase the likelihood of moderate to high diabetes distress.

Assessing diabetes distress in patients with cognitive impairment, poor executive functioning, or other psychological limitations is particularly difficult, however, as no diabetes distress measures take such deficits into account. Thus, primary care physicians without expertise in neuropsychology should consider referring patients with such problems to specialists for assessment.

The progressive nature of diabetes also highlights the need for primary care physicians to periodically screen for diabetes distress and engage in ongoing discussions about what type of care is best for individual patients, and why. When developing or updating treatment plans and making recommendations, it is crucial to consider the impact the treatment would likely have on the patient’s physical and mental health and to explicitly inquire about and acknowledge his or her values and preferences for care.40-44

It is also important to remain aware of socioeconomic changes—in employment, insurance coverage, and living situations, for example—which are not addressed in the screening tools.

Moderate to high diabetes distress scores, as well as individual items patients identify as “very serious” problems, represent clinical red flags that should be the focus of careful discussion during a medical visit. Patients with moderate to high distress should be referred to a therapist trained in cognitive behavioral therapy or problem-solving therapy. Physicians who lack access to such resources can incorporate cognitive behavioral and problem-solving techniques into patient discussion. (See “Directing help where it’s most needed.”) All patients should be referred to a certified diabetes educator—a key component of diabetes care.45,46

SIDEBAR

Directing help where it's most needed

CASE 1 ›

Conduct a behavioral experiment

Fred J, a 67-year-old diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 6 years ago, comes in for a diabetes check-up. He is a new patient who recently retired from his job as a contractor and was referred by a colleague. In response to a question about his diabetes management, Mr. J tells you he’s having a hard time.

“I get down on myself,” the patient says. “I take my medications every day at the exact same time, but when I test my sugar, it’s 260 or 280. I know I did this to myself. If only I weighed less, ate better, or exercised more.”

At other times, “I think, 'Why bother?'” Mr. J adds. “I feel like there’s nothing I can do to make it better.”

The DDS-2 screen you gave Mr. J bears out his high level of distress and his fear of complications. He tells you about an aunt who “had diabetes like me and had to go on dialysis, then died 2 years later.” When you ask what he fears most, Mr. J says he worries about kidney failure. “I don’t want to go on dialysis,” he insists.

You take the opportunity to point out that nephropathy is not inevitable and that he can perform self-care behaviors now that will prevent or delay kidney complications.

You also decide to try a cognitive behavioral technique in an attempt to change his thought process. You ask Mr. J to agree to a week-long behavioral experiment to examine the effect of walking for 30 minutes each day.

He agrees. You advise him to write down his predictions before he begins the experiment and then to keep a log, checking and recording his glucose levels before and after each walk. You schedule a follow-up visit to discuss the results, hoping that a reduction in blood glucose levels will convince Mr. J that exercise is beneficial to his diabetes.

CASE 2 ›

Identify the problem; brainstorm with the patient

Susan T, a 46-year-old with a husband and 2 teenage children, comes in for her 3-month diabetes check-up. At her last visit, she expressed concerns about her family’s lack of cooperation as she struggled to change her diet. This time, she appears frustrated and distraught.

Your nurse administered the PAID-5 while Ms. T was in the waiting room and entered her score—8, indicating high diabetes distress—in the electronic medical record. You ask Ms. T what’s happening, knowing that encouraging her to verbalize her feelings is a way to increase her trust and help alleviate her concerns.

You also try the following problem-solving technique:

Define the problem. Ms. T is having a hard time maintaining a healthy diet. Her husband and children refuse to eat the healthy meals she prepares and want her to cook separate dinners for them.

Identify challenges. The patient works full-time and does not have the time or energy to cook separate meals. In addition, she is upset by her family’s lack of support in her efforts to control her disease.

Brainstorm multiple solutions:

1) Ms. T can prepare all of her own meals for the work week on Sunday, then cook for the others when she returns from work.

2) Her husband and children can make their own dinner if they do not want to eat the healthier meals she prepares.

3) The patient can join a diabetes support group where she will meet, and possibly learn from, other patients who may be struggling with diabetes self-care.

4) Ms. T can ask her husband and children to come to her next diabetes check-up so they can learn about the importance of family support in diabetes management directly from you.

5) The patient’s family can receive information about a healthy diabetes diet from a certified diabetes educator.

Decide on appropriate solutions. The patient agrees to try and prepare her weekday meals on Sunday so that she is not tempted to eat less healthy options. She also agrees to bring her family to her next diabetes check-up and to diabetes education classes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, 35 W. Green Drive, Athens, OH 45701; beverle1@ohio.edu.

Managing diabetes is a complex undertaking, with an extensive regimen of self-care—including regular exercise, meal planning, blood glucose monitoring, medication scheduling, and multiple visits—that is critically linked to glycemic control and the prevention of complications. Incorporating all of these elements into daily life can be daunting.1-3

In fact, nearly half of US adults with diabetes fail to meet the recommended targets.4 This leads to frustration, which often manifests in psychosocial problems that further hamper efforts to manage the disease.5-10 The most notable is a psychosocial disorder known as diabetes distress, which affects close to 45% of those with diabetes.11,12

It is important to note that diabetes distress is not a psychiatric disorder;13 rather, it is a broad affective reaction to the stress of living with this chronic and complex disease.14,15 By negatively affecting adherence to a self-care regimen, diabetes distress contributes to worsening glycemic control and increasing morbidity.16-18

Recognizing that about 80% of those with diabetes are treated in primary care settings,19 we wrote this review to call your attention to diabetes distress, alert you to brief screening tools that can easily be incorporated into clinic visits, and offer guidance in matching proposed interventions to the aspects of diabetes self-management that cause patients the greatest distress.

Diabetes distress: What it is, what it’s not

For patients with type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress centers around 4 main issues:

- frustration with the demands of self-care;

- apprehension about the future and the possibility of developing serious complications;

- concern about both the quality and the cost of required medical care; and

- perceived lack of support from family and/or friends.11,12,20

As mentioned earlier, diabetes distress is not a psychiatric condition and should not be confused with major depressive disorder (MDD). Here’s help in telling the difference.

For starters, a diagnosis of depression is symptom-based.13 MDD requires the presence of at least 5 of the 9 symptoms defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth ed. (DSM-5)—eg, persistent feelings of worthlessness or guilt, sleep disturbances, lack of interest in normal activities—for at least 2 weeks.21 What’s more, the diagnostic criteria for MDD do not specify a cause or disease process. Nor do they distinguish between a pathological response and an expected reaction to a stressful life event.22 Further, depression measures reflect symptoms (eg, hyperglycemia), as well as stressful experiences resulting from diabetes self-care, which may contribute to the high rate of false positives or incorrect diagnoses of MDD and missed diagnoses of diabetes distress.23

Unlike MDD, diabetes distress has a specific cause—diabetes—and can best be understood as an emotional response to a demanding health condition.13 And, because the source of the problem is identified, diabetes distress can be treated with specific interventions targeting the areas causing the highest levels of stress.

When a psychiatric condition and diabetes distress overlap

MDD, anxiety disorders, and diabetes distress are all common in patients with diabetes,24 and the co-occurrence of a psychiatric disorder and diabetes distress is high.25 Thus, it is important not only to identify cases of diabetes distress but also to consider comorbid depression and/or anxiety in patients with diabetes distress.

More often, though, it is the other way around, according to the Distress and Depression in Diabetes (3D) study. The researchers recently found that 84% of patients with moderate or high diabetes distress did not fulfill the criteria for MDD, but that 67% of diabetes patients with MDD also had moderate or high diabetes distress.13,15,17,25

The data highlight the importance of screening patients with a dual diagnosis of diabetes and MDD for diabetes distress. Keep in mind that individuals diagnosed with both diabetes distress and a comorbid psychiatric condition may require more complex and intensive treatment than those with either diabetes distress or MDD alone.25

Screening for diabetes distress

Diabetes distress can be easily assessed using one of several patient-reported outcome measures. Six validated measures, ranging in length from one to 28 questions, are designed for use in primary care (TABLE).26-30 Some of the measures are easily accessible online; others require subscription to MEDLINE.

Problem Areas in Diabetes (PAID): There are 3 versions of PAID—a 20-item screen assessing a broad range of feelings related to living with diabetes and its treatment, a 5-item version (PAID-5) with high rates of sensitivity (95%) and specificity (89%), and a single-item test (PAID-1) that is highly correlated with the longer version.26,27

Diabetes Distress Scale (DDS): This tool is available in a 17-item measure assessing diabetes distress as it relates to the emotional burden, physician-related distress, regimen-related distress, and interpersonal distress.28 DDS is also available in a short form (DDS-2) with 2 items29 and a 28-item scale specifically for patients with type 1 diabetes.30 T1-DDS, the only diabetes distress measure focused on this particular patient population, assesses the 7 sources of distress found to be common among adults with type 1 diabetes: powerlessness, negative social perceptions, physician distress, friend/family distress, hypoglycemia distress, management distress, and eating distress.

Studies have shown that not only do those with type 1 diabetes experience different stressors compared with their type 2 counterparts, but that they tend to experience distress differently. For patients with type 1 diabetes, for example, powerlessness ranked as the highest source of distress, followed by eating distress and hypoglycemia distress. These sources of distress differ from the regimen distress, emotional burden, interpersonal distress, and physician distress identified by those with type 2 diabetes.30

How to respond to diabetes distress

Diabetes distress is easier to identify than to successfully treat. Few validated treatments for diabetes distress exist and, to our knowledge, only 2 studies have assessed interventions aimed at reduction of such distress.31,32

The REDEEM trial31 recruited adults with type 2 diabetes and diabetes distress to participate in a 12-month randomized controlled trial (RCT). The trial had 3 arms, comparing the effectiveness of a computer-assisted self-management (CASM) program alone, a CASM program plus in-person diabetes distress-specific problem-solving therapy, and a computer-assisted minimally supportive intervention. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (using the DDS scale and subscales), along with self-management behaviors and HbA1c.

Participants in all 3 arms showed significant reductions in total diabetes distress and improvements in self-management behaviors, with no significant differences among the groups. No differences in HbA1c were found. However, those in the CASM program plus distress-specific therapy arm showed a larger reduction in regimen distress compared with the other 2 groups.31

The DIAMOS trial32 recruited adults who had type 1 or type 2 diabetes, diabetes distress, and subclinical depressive symptoms for a 2-arm RCT. One group underwent cognitive behavioral interventions, while the controls had standard group-based diabetes education. The main outcomes included diabetes distress (measured via the PAID scale), depressive symptoms, well-being, diabetes self-care, diabetes acceptance, satisfaction with diabetes treatment, HbA1c, and subclinical inflammation.

The intervention group showed greater improvement in diabetes distress and depressive symptoms compared with the control group, but no differences in well-being, self-care, treatment satisfaction, HbA1c, or subclinical inflammation were observed.32

Both studies support the use of problem-solving therapy and cognitive behavioral interventions for patients with diabetes distress. Future research should evaluate the effectiveness of these interventions in the primary care setting.

What else to offer when challenges mount?

Diabetes is a progressive disease, and most patients experience multiple challenges over time. These typically include complications and comorbidities, physical limitations, polypharmacy, hypoglycemia, and cognitive impairment, as well as changes in everything from medication and lifestyle to insurance coverage and social support.33,34 All increase the risk for diabetes distress, as well as related psychiatric conditions.

Aging and diabetes are independent risk factors for cognitive impairment, for example, and the presence of both increases this risk.35 What’s more, diabetes alone is associated with poorer executive function,36-38 the higher-level cognitive processes that allow individuals to engage in independent, purposeful, and flexible goal-related behaviors. Both poor cognitive function and impaired executive function interfere with the ability to perform self-care behaviors such as adjusting insulin doses, drawing insulin into a syringe, or dialing an insulin dose with an insulin pen.39 This in turn can lead to frustration and increase the likelihood of moderate to high diabetes distress.

Assessing diabetes distress in patients with cognitive impairment, poor executive functioning, or other psychological limitations is particularly difficult, however, as no diabetes distress measures take such deficits into account. Thus, primary care physicians without expertise in neuropsychology should consider referring patients with such problems to specialists for assessment.

The progressive nature of diabetes also highlights the need for primary care physicians to periodically screen for diabetes distress and engage in ongoing discussions about what type of care is best for individual patients, and why. When developing or updating treatment plans and making recommendations, it is crucial to consider the impact the treatment would likely have on the patient’s physical and mental health and to explicitly inquire about and acknowledge his or her values and preferences for care.40-44

It is also important to remain aware of socioeconomic changes—in employment, insurance coverage, and living situations, for example—which are not addressed in the screening tools.

Moderate to high diabetes distress scores, as well as individual items patients identify as “very serious” problems, represent clinical red flags that should be the focus of careful discussion during a medical visit. Patients with moderate to high distress should be referred to a therapist trained in cognitive behavioral therapy or problem-solving therapy. Physicians who lack access to such resources can incorporate cognitive behavioral and problem-solving techniques into patient discussion. (See “Directing help where it’s most needed.”) All patients should be referred to a certified diabetes educator—a key component of diabetes care.45,46

SIDEBAR

Directing help where it's most needed

CASE 1 ›

Conduct a behavioral experiment

Fred J, a 67-year-old diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 6 years ago, comes in for a diabetes check-up. He is a new patient who recently retired from his job as a contractor and was referred by a colleague. In response to a question about his diabetes management, Mr. J tells you he’s having a hard time.

“I get down on myself,” the patient says. “I take my medications every day at the exact same time, but when I test my sugar, it’s 260 or 280. I know I did this to myself. If only I weighed less, ate better, or exercised more.”

At other times, “I think, 'Why bother?'” Mr. J adds. “I feel like there’s nothing I can do to make it better.”

The DDS-2 screen you gave Mr. J bears out his high level of distress and his fear of complications. He tells you about an aunt who “had diabetes like me and had to go on dialysis, then died 2 years later.” When you ask what he fears most, Mr. J says he worries about kidney failure. “I don’t want to go on dialysis,” he insists.

You take the opportunity to point out that nephropathy is not inevitable and that he can perform self-care behaviors now that will prevent or delay kidney complications.

You also decide to try a cognitive behavioral technique in an attempt to change his thought process. You ask Mr. J to agree to a week-long behavioral experiment to examine the effect of walking for 30 minutes each day.

He agrees. You advise him to write down his predictions before he begins the experiment and then to keep a log, checking and recording his glucose levels before and after each walk. You schedule a follow-up visit to discuss the results, hoping that a reduction in blood glucose levels will convince Mr. J that exercise is beneficial to his diabetes.

CASE 2 ›

Identify the problem; brainstorm with the patient

Susan T, a 46-year-old with a husband and 2 teenage children, comes in for her 3-month diabetes check-up. At her last visit, she expressed concerns about her family’s lack of cooperation as she struggled to change her diet. This time, she appears frustrated and distraught.

Your nurse administered the PAID-5 while Ms. T was in the waiting room and entered her score—8, indicating high diabetes distress—in the electronic medical record. You ask Ms. T what’s happening, knowing that encouraging her to verbalize her feelings is a way to increase her trust and help alleviate her concerns.

You also try the following problem-solving technique:

Define the problem. Ms. T is having a hard time maintaining a healthy diet. Her husband and children refuse to eat the healthy meals she prepares and want her to cook separate dinners for them.

Identify challenges. The patient works full-time and does not have the time or energy to cook separate meals. In addition, she is upset by her family’s lack of support in her efforts to control her disease.

Brainstorm multiple solutions:

1) Ms. T can prepare all of her own meals for the work week on Sunday, then cook for the others when she returns from work.

2) Her husband and children can make their own dinner if they do not want to eat the healthier meals she prepares.

3) The patient can join a diabetes support group where she will meet, and possibly learn from, other patients who may be struggling with diabetes self-care.

4) Ms. T can ask her husband and children to come to her next diabetes check-up so they can learn about the importance of family support in diabetes management directly from you.

5) The patient’s family can receive information about a healthy diabetes diet from a certified diabetes educator.

Decide on appropriate solutions. The patient agrees to try and prepare her weekday meals on Sunday so that she is not tempted to eat less healthy options. She also agrees to bring her family to her next diabetes check-up and to diabetes education classes.

CORRESPONDENCE

Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD, Department of Family Medicine, Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, 35 W. Green Drive, Athens, OH 45701; beverle1@ohio.edu.

1. Gafarian CT, Heiby EM, Blair P, et al. The diabetes time management questionnaire. Diabetes Educator. 1999;25:585-592.

2. Wdowik MJ, Kendall PA, Harris MA. College students with diabetes: using focus groups and interviews to determine psychosocial issues and barriers to control. Diabetes Educator. 1997;23:558-562.

3. Rubin RR. Psychological issues and treatment for people with diabetes. J Clin Psych. 2001;57:457-478.

4. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999-2010. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:287-288.

5. Lloyd CE, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: Review of the links. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18:121-127.

6. Weinger K. Psychosocial issues and self-care. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(6 suppl): S34-S38.

7. Weinger K, Jacobson AM. Psychosocial and quality of life correlates of glycemic control during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Education Counseling. 2001;42:123-131.

8. Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: an RRNeST study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354-360.

9. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2222-2227.

10. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1102-1107.

11. Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RI, et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2013;30:767-777.

12. Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky W, et al. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful?: establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:259-264.

13. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

14. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, et al. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetic Med. 2009;26:622-627.

15. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:542-548.

16. Gonzalez JS, Delahanty LM, Safren SA, et al. Differentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2822-1825.

17. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, et al. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:23-28.

18. Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, Devellis BM, et al. Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: a systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33:1080-1103; 1104-1086.

19. Peterson KA, Radosevich DM, O’Connor PJ, et al. Improving diabetes care in practice: findings from the TRANSLATE trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2238-2243.

20. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA. The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1034-1036.

21. Cole J, McGuffin P, Farmer AE. The classification of depression: are we still confused? Br J Psychiatr. 2008;192:83-85.

22. Wakefield JC. The concept of mental disorder. On the boundary between biological facts and social values. Am Psychologist. 1992;47:373-388.

23. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

24. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278-3285.

25. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. A longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1096-1101.

26. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754-760.

27. McGuire BE, Morrison TG, Hermanns N, et al. Short-form measures of diabetes-related emotional distress: the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID)-5 and PAID-1. Diabetologia. 2010;53:66-69.

28. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626-631.

29. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Mullan JT, et al. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:246-252.

30. Fisher L, Polonsky WH, Hessler DM, et al. Understanding the sources of diabetes distress in adults with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:572-577.

31. Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2551-2558.

32. Hermanns N, Schmitt A, Gahr A, et al. The effect of a Diabetes-Specific Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Program (DIAMOS) for patients with diabetes and subclinical depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:551-560.

33. Weinger K, Beverly EA, Smaldone A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. Western J Nurs Res. 2014;36:1272-1298.

34. Beverly EA, Ritholz MD, Shepherd C, et al. The psychosocial challenges and care of older adults with diabetes: “can’t do what I used to do; can’t be who I once was.” Curr Diabetes Rep. 2016;16:48.

35. Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2009;4:e4144.

36. Thabit H, Kyaw TT, McDermott J, et al. Executive function and diabetes mellitus—a stone left unturned? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8:109-115.

37. McNally K, Rohan J, Pendley JS, et al. Executive functioning, treatment adherence, and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1159-1162.

38. Rucker JL, McDowd JM, Kluding PM. Executive function and type 2 diabetes: putting the pieces together. Phys Ther. 2012;92:454-462.

39. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2650-2664.

40. Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006;295:1935-1940.

41. Oftedal B, Karlsen B, Bru E. Life values and self-regulation behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2548-2556.

42. Morrow AS, Haidet P, Skinner J, et al. Integrating diabetes self-management with the health goals of older adults: a qualitative exploration. Patient Education Counseling. 2008;72:418-423.

43. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:306-311.

44. Beverly EA, Wray LA, LaCoe CL, et al. Listening to older adults’ values and preferences for Type 2 diabetes care: a qualitative study. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27:44-49.

45. American Association of Diabetes Educators. Why refer for diabetes education? American Association of Diabetes Educators. Available at: https://www.diabeteseducator.org/practice/provider-resources/why-refer-for-diabetes-education. Accessed August 15, 2016.

46. Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363:1589-1597.

1. Gafarian CT, Heiby EM, Blair P, et al. The diabetes time management questionnaire. Diabetes Educator. 1999;25:585-592.

2. Wdowik MJ, Kendall PA, Harris MA. College students with diabetes: using focus groups and interviews to determine psychosocial issues and barriers to control. Diabetes Educator. 1997;23:558-562.

3. Rubin RR. Psychological issues and treatment for people with diabetes. J Clin Psych. 2001;57:457-478.

4. Ali MK, Bullard KM, Gregg EW. Achievement of goals in US diabetes care, 1999-2010. New Engl J Med. 2013;369:287-288.

5. Lloyd CE, Smith J, Weinger K. Stress and diabetes: Review of the links. Diabetes Spectrum. 2005;18:121-127.

6. Weinger K. Psychosocial issues and self-care. Am J Nurs. 2007;107(6 suppl): S34-S38.

7. Weinger K, Jacobson AM. Psychosocial and quality of life correlates of glycemic control during intensive treatment of type 1 diabetes. Patient Education Counseling. 2001;42:123-131.

8. Albright TL, Parchman M, Burge SK. Predictors of self-care behavior in adults with type 2 diabetes: an RRNeST study. Fam Med. 2001;33:354-360.

9. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Cagliero E, et al. Depression, self-care, and medication adherence in type 2 diabetes: relationships across the full range of symptom severity. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:2222-2227.

10. Gonzalez JS, Safren SA, Delahanty LM, et al. Symptoms of depression prospectively predict poorer self-care in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1102-1107.

11. Nicolucci A, Kovacs Burns K, Holt RI, et al. Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs second study (DAWN2): cross-national benchmarking of diabetes-related psychosocial outcomes for people with diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2013;30:767-777.

12. Fisher L, Hessler DM, Polonsky W, et al. When is diabetes distress clinically meaningful?: establishing cut points for the Diabetes Distress Scale. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:259-264.

13. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

14. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Skaff MM, et al. Predicting diabetes distress in patients with Type 2 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Diabetic Med. 2009;26:622-627.

15. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. Clinical depression versus distress among patients with type 2 diabetes: not just a question of semantics. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:542-548.

16. Gonzalez JS, Delahanty LM, Safren SA, et al. Differentiating symptoms of depression from diabetes-specific distress: relationships with self-care in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:2822-1825.

17. Fisher L, Mullan JT, Arean P, et al. Diabetes distress but not clinical depression or depressive symptoms is associated with glycemic control in both cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:23-28.

18. Fisher EB, Thorpe CT, Devellis BM, et al. Healthy coping, negative emotions, and diabetes management: a systematic review and appraisal. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33:1080-1103; 1104-1086.

19. Peterson KA, Radosevich DM, O’Connor PJ, et al. Improving diabetes care in practice: findings from the TRANSLATE trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2238-2243.

20. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Strycker LA. The relationship between diabetes distress and clinical depression with glycemic control among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1034-1036.

21. Cole J, McGuffin P, Farmer AE. The classification of depression: are we still confused? Br J Psychiatr. 2008;192:83-85.

22. Wakefield JC. The concept of mental disorder. On the boundary between biological facts and social values. Am Psychologist. 1992;47:373-388.

23. Fisher L, Gonzalez JS, Polonsky WH. The confusing tale of depression and distress in patients with diabetes: a call for greater clarity and precision. Diabetic Med. 2014;31:764-772.

24. Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE. Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3278-3285.

25. Fisher L, Skaff MM, Mullan JT, et al. A longitudinal study of affective and anxiety disorders, depressive affect and diabetes distress in adults with Type 2 diabetes. Diabetic Med. 2008;25:1096-1101.

26. Polonsky WH, Anderson BJ, Lohrer PA, et al. Assessment of diabetes-related distress. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:754-760.

27. McGuire BE, Morrison TG, Hermanns N, et al. Short-form measures of diabetes-related emotional distress: the Problem Areas in Diabetes Scale (PAID)-5 and PAID-1. Diabetologia. 2010;53:66-69.

28. Polonsky WH, Fisher L, Earles J, et al. Assessing psychosocial distress in diabetes: development of the diabetes distress scale. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:626-631.

29. Fisher L, Glasgow RE, Mullan JT, et al. Development of a brief diabetes distress screening instrument. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6:246-252.

30. Fisher L, Polonsky WH, Hessler DM, et al. Understanding the sources of diabetes distress in adults with type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29:572-577.

31. Fisher L, Hessler D, Glasgow RE, et al. REDEEM: a pragmatic trial to reduce diabetes distress. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:2551-2558.

32. Hermanns N, Schmitt A, Gahr A, et al. The effect of a Diabetes-Specific Cognitive Behavioral Treatment Program (DIAMOS) for patients with diabetes and subclinical depression: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:551-560.

33. Weinger K, Beverly EA, Smaldone A. Diabetes self-care and the older adult. Western J Nurs Res. 2014;36:1272-1298.

34. Beverly EA, Ritholz MD, Shepherd C, et al. The psychosocial challenges and care of older adults with diabetes: “can’t do what I used to do; can’t be who I once was.” Curr Diabetes Rep. 2016;16:48.

35. Lu FP, Lin KP, Kuo HK. Diabetes and the risk of multi-system aging phenotypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2009;4:e4144.

36. Thabit H, Kyaw TT, McDermott J, et al. Executive function and diabetes mellitus—a stone left unturned? Curr Diabetes Rev. 2012;8:109-115.

37. McNally K, Rohan J, Pendley JS, et al. Executive functioning, treatment adherence, and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1159-1162.

38. Rucker JL, McDowd JM, Kluding PM. Executive function and type 2 diabetes: putting the pieces together. Phys Ther. 2012;92:454-462.

39. Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, et al. Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2650-2664.

40. Durso SC. Using clinical guidelines designed for older adults with diabetes mellitus and complex health status. JAMA. 2006;295:1935-1940.

41. Oftedal B, Karlsen B, Bru E. Life values and self-regulation behaviours among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Clin Nurs. 2010;19:2548-2556.

42. Morrow AS, Haidet P, Skinner J, et al. Integrating diabetes self-management with the health goals of older adults: a qualitative exploration. Patient Education Counseling. 2008;72:418-423.

43. Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH. Self-reported goals of older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:306-311.

44. Beverly EA, Wray LA, LaCoe CL, et al. Listening to older adults’ values and preferences for Type 2 diabetes care: a qualitative study. Diabetes Spectrum. 2014;27:44-49.

45. American Association of Diabetes Educators. Why refer for diabetes education? American Association of Diabetes Educators. Available at: https://www.diabeteseducator.org/practice/provider-resources/why-refer-for-diabetes-education. Accessed August 15, 2016.

46. Ismail K, Winkley K, Rabe-Hesketh S. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of psychological interventions to improve glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363:1589-1597.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Educate patients about diabetes distress, explaining that diabetes is manageable and that neither complications nor diabetes distress is inevitable. C

› Empower patients to take an active role in self-management of diabetes, encouraging them to express their concerns and ask open-ended questions. A

› Support shared decision-making by inquiring about patients’ values and treatment preferences, presenting options, and reviewing the risks and benefits of each. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series