User login

The past 10 years have brought a formidable challenge to the clinical arena, as carbapenems, until now the most reliable antibiotics against Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli, and other Enterobacteriaceae, are becoming increasingly ineffective.

Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) pose a serious threat to hospitalized patients. Moreover, CRE often demonstrate resistance to many other classes of antibiotics, thus limiting our therapeutic options. Furthermore, few new antibiotics are in line to replace carbapenems. This public health crisis demands redefined and refocused efforts in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of infections in hospitalized patients.

Here, we present an overview of CRE and discuss avenues to escape a new era of untreatable infections.

INCREASED USE OF CARBAPENEMS AND EMERGENCE OF RESISTANCE

Developed in the 1980s, carbapenems are derivatives of thyanamycin. Imipenem and meropenem, the first members of the class, had a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity that included coverage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, adequately positioning them for the treatment of nosocomial infections. Back then, nearly all Enterobacteriaceae were susceptible to carbapenems.1

In the 1990s, Enterobacteriaceae started to develop resistance to cephalosporins—till then, the first-line antibiotics for these organisms—by acquiring extended-spectrum betalactamases, which inactivate those agents. Consequently, the use of cephalosporins had to be restricted, while carbapenems, which remained impervious to these enzymes, had to be used more.2 In pivotal international studies in the treatment of infections caused by strains of K pneumoniae that produced these inactivating enzymes, outcomes were better with carbapenems than with cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.3,4

Ertapenem, a carbapenem without antipseudomonal activity and highly bound to protein, was released in 2001. Its prolonged half-life permitted once-daily dosing, which positioned it as an option for treating infections in community dwellers.5 Doripenem is the newest member of the class of carbapenems, and its spectrum of activity is similar to that of imipenem and meropenem and includes P aeruginosa.6 The use of carbapenems, measured in a representative sample of 35 university hospitals in the United States, increased by 59% between 2002 and 2006.7

In the early 2000s, carbapenem resistance in K pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae was rare in North America. But then, after initial outbreaks occurred in hospitals in the Northeast (especially New York City), CRE began to spread throughout the United States. By 2009–2010, the National Healthcare Safety Network from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that 12.8% of K pneumoniae isolates associated with bloodstream infections were resistant to carbapenems.8

In March 2013, the CDC disclosed that 3.9% of short-stay acute-care hospitals and 17.8% of long-term acute-care hospitals reported at least one CRE health care-associated infection in 2012. CRE had extended to 42 states, and the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae that are CRE had increased fourfold over the past 10 years.9

Coinciding with the increased use of carbapenems, multiple factors and modifiers likely contributed to the dramatic increase in CRE. These include use of other antibiotics in humans and animals, their relative penetration and selective effect on the gut microbiota, case-mix and infection control practices in different health care settings, and travel patterns.

POWERFUL ENZYMES THAT TRAVEL FAR

Bacterial acquisition of carbapenemases, enzymes that inactivate carbapenems, is crucial to the emergence of CRE. The enzyme in the sentinel carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae isolate found in 1996 in North Carolina was designated K pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-1). This mechanism also conferred resistance to all cephalosporins, aztreonam, and beta-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid and tazobactam.10

KPC-2 (later determined to be identical to KPC-1) was found in K pneumoniae from Baltimore, and KPC-3 caused an early outbreak in New York City.11,12 To date, 12 additional variants of blaKPC, the gene encoding for the KPC enzyme, have been described.13

The genes encoding carbapenemases are usually found on plasmids or other common mobile genetic elements.14 These genetic elements allow the organism to acquire genes conferring resistance to other classes of antimicrobials, such as aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and fluoroquinolone-resistance determinants, and beta-lactamases.15,16 The result is that CRE isolates are increasingly multidrug-resistant (ie, resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials), extensively drug-resistant (ie, resistant to all but one or two classes), or pandrug-resistant (ie, resistant to all available classes of antibiotics).17 Thus, up to 98% of KPC-producing K pneumoniae are resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 90% are resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 60% are resistant to gentamicin or amikacin.15

The mobility of these genetic elements has also allowed for dispersion into diverse Enterobacteriaceae such as E coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Salmonella species. Furthermore, KPC has been described in non-Enterobacteriaceae such as Acinetobacter baumannii and P aeruginosa.

Extending globally, KPC is now endemic in the Mediterranean basin, including Israel, Greece, and Italy; in South America, especially Colombia, Argentina, and Brazil; and in China.18 Most interesting is the intercontinental transfer of these strains: it has been documented that the index patient with KPC-producing K pneumoniae in Medellin, Colombia, came from Israel to undergo liver transplantation.19 Likewise, KPC-producing K pneumoniae in France and Israel could be linked epidemiologically and genetically to the predominant US strain.20,21

Even more explosive has been the surge of another carbapenemase, the Ambler Class B New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM-1. Initially reported in a urinary isolate of K pneumoniae from a Swedish patient who had been hospitalized in New Delhi in 2008, NDM-1 was soon found throughout India, in Pakistan, and in the United Kingdom.22 Interestingly, several of the UK patients with NDM-1-harboring bacteria had received organ transplants in the Indian subcontinent. Reports from elsewhere in Europe, Australia, and Africa followed suit, usually with a connection to the Indian subcontinent epicenter. In contrast, several other cases in Europe were traced to the Balkans, where there appears to be another focus of NDM-1.23

Penetration of NDM-1 into North America has begun, with cases and outbreaks reported in several US and Canadian regions, and in a military medical facility in Afghanistan. In several of these instances, there has been a documented link with travel and hospitalizations overseas.24–27 However, no such link with travel could be established in a recent outbreak in Ontario.27

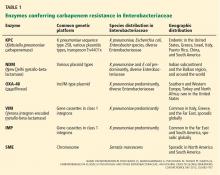

In addition, resistance to carbapenems may result from other enzymes (Table 1), or from combinations of changes in outer membrane porins and the production of extended spectrum beta-lactamases or other cephalosporinases.28

DEADLY IMPACT ON THE MOST VULNERABLE

Regardless of the resistance pattern, Enterobacteriaceae are an important cause of health care-associated infections, including urinary and bloodstream infections in patients with indwelling catheters, pneumonia (often in association with mechanical ventilation), and, less frequently, infections of skin and soft tissues and the central nervous system.29–31

Several studies have examined the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with CRE infections. Those typically affected are elderly and debilitated and have multiple comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression. They are heavily exposed to health care with frequent antecedent hospitalizations and invasive procedures. Furthermore, they are often severely ill and require intensive care. Patients infected with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae, compared with those with carbapenem-susceptible strains, are more likely to have undergone organ or stem cell transplantation or mechanical ventilation, and to have had a longer hospital stay before infection.

They also experience a high mortality rate, which ranges from 30% in patients with nonbacteremic infections to 72% in series of patients with liver transplants or bloodstream infections.32–37

More recently, CRE has been reported in other vulnerable populations, such as children with critical illness or cancer and in burn patients.38–40

Elderly and critically ill patients with bacteremia originating from a high-risk source (eg, pneumonia) typically face the most adverse outcomes. With increasing drug resistance, inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy is more commonly seen and may account for some of these poor outcomes.37,41

LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES IN THE EYE OF THE STORM

A growing body of evidence suggests that long-term care facilities play a crucial role in the spread of CRE.

In an investigation into carbapenem-resistant A baumanii and K pneumoniae in a hospital system,36 75% of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae were admitted from long-term care facilities, and only 1 of 13 patients was discharged home.

In a series of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae bloodstream infections, 42% survived their index hospital stay. Of these patients, only 32% were discharged home, and readmissions were very common.32

Admission from a long-term care facility or transfer from another hospital is significantly associated with carbapenem resistance in patients with Enterobacteriaceae.42 Similarly, in Israel, a large reservoir of CRE was found in postacute care facilities.43

It is clear that long-term care residents are at increased risk of colonization and infection with CRE. However, further studies are needed to evaluate whether this simply refects an overlap in risk factors, or whether significant patient-to-patient transmission occurs in these settings.

INFECTION CONTROL TAKES CENTER STAGE

It is important to note that risk factors for CRE match those of various nosocomial infections, including other resistant gram-negative bacilli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Candida species, and Clostridium difficile; in fact, CRE often coexist with other multidrug-resistant organisms.44,45

Common risk factors include residence in a long-term care facility, an intensive care unit stay, use of lines and catheters, and antibiotic exposure. This commonality of risk factors implies that systematic infection-prevention measures will have an impact on the prevalence and incidence rates of multidrug-resistant organism infections across the board, CRE included. It should be emphasized that strict compliance with hand hygiene is still the foundation of any infection-prevention strategy.

Infection prevention and the control of transmission of CRE in long-term care facilities pose unique challenges. Guidelines from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control recommend the use of contact precautions for patients with multidrug-resistant organisms, including CRE, who are ill and totally dependent on health care workers for activities of daily living or whose secretions or drainage cannot be contained. These same guidelines advise against attempting to eradicate multidrug-resistant organism colonization status.46

In acute care facilities, Best Infection Control Practices from the CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee encourage mechanisms for the rapid recognition and reporting of CRE cases to infection prevention personnel so that contact precautions can be implemented. Furthermore, facilities without CRE cases should carry out periodic laboratory reviews to identify cases, and patients exposed to CRE cases should be screened with surveillance cultures.47

Outbreaks of CRE may require extraordinary infection control measures. An approach combining point-prevalence surveillance of colonization, detection of environmental and common-equipment contamination, with the implementation of a bundle consisting of chlorhexidine baths, cohorting of colonized patients and health care personnel, increased environmental cleaning, and staff education may be effective in controlling outbreaks of CRE.48

Nevertheless, control of CRE may prove exceptionally difficult. A recent high-profile outbreak of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Maryland caused infections in 18 patients, 11 of whom died.49 Of note, carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected in this outbreak in both respiratory equipment and sink drains. The outbreak was ultimately contained by detection through surveillance cultures and by strict cohorting of colonized patients, which minimized common medical equipment and personnel between affected patients and other patients in the hospital. Additionally, rooms were sanitized with hydrogen peroxide vapor, and sinks and drains where carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected were removed.

CHALLENGES IN THE MICROBIOLOGY LABORATORY

Adequate treatment and control of CRE infections is predicated upon their accurate and prompt diagnosis from patient samples in the clinical microbiology laboratory.50

Traditional and current culture-based methods take several days to provide that information, delaying effective antibiotic therapy and permitting the transmission of undetected CRE. Furthermore, interpretative criteria of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of carbapenems recently required readjustment, as many KPC-producing strains of K pneumoniae had MICs below the previous breakpoint of resistance. In the past, this contributed to instances of “silent” dissemination of KPC-producing K pneumoniae.51

In contrast, using the new lower breakpoints of resistance for carbapenems without using a phenotypic test such as the modified Hodge test or the carbapenem-EDTA combination tests will result in a lack of differentiation between various mechanisms of carbapenem resistance.28,52,53 This may be clinically relevant, as the clinical response to carbapenem therapy may vary depending on the mechanism of resistance.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES APPLY

In treating patients infected with CRE, clinicians need to strictly observe general principles of infectious disease management to ensure the best possible outcomes. These include:

Timely and accurate diagnosis, as discussed above.

Source control, which should include drainage of any infected collections, and removal of lines, devices, and urinary catheters.

Distinguishing between infection and colonization. CRE are often encountered as urinary isolates, and the distinction between asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection may be extremely difficult, especially in residents of long-term care facilities with chronic indwelling catheters, who are thegroup at highest risk of CRE colonization and infection. Urinalysis may be helpful in the absence of pyuria, as this rules out an infection; however, it must be emphasized that the presence of pyuria is not a helpful feature, as pyuria is common in both asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection.54 Symptoms should be carefully evaluated in every patient with bacteriuria, and urinary tract infection should be a diagnosis of exclusion in patients with functional symptoms such as confusion or falls.

Selection of the most appropriate antibiotic regimen. While the emphasis is often on the antibiotic regimen, the above elements should not be neglected.

A DWINDLING THERAPEUTIC ARSENAL

Clinicians treating CRE infections are left with only a few antibiotic options. These options are generally limited by a lack of clinical data on efficacy, as well as by concerns about toxicity. These “drugs of last resort” include polymyxins (such as colistin), aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and fosfomycin. The role of carbapenem therapy, potentially in combination regimens, in a high-dose prolonged infusion, or even “double carbapenem therapy” remains to be determined.37,55,56

Colistin

Colistin is one of the first-line agents for treating CRE infections. First introduced in the 1950s, its use was mostly abandoned in favor of aminoglycosides. A proportion of the data on safety and efficacy of colistin, therefore, is based on older, less rigorous studies.

Neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity are the two main concerns with colistin, and while the incidence of these adverse events does appear to be lower with modern preparations, it is still substantial.57 Dosing issues have not been completely clarified either, especially in relation to renal clearance and in patients on renal replacement therapy.58,59 Unfortunately, there have been reports of outbreaks of CRE displaying resistance to colistin.60

Tigecycline

Tigecycline is a newer antibiotic of the glycylcycline class. Like colistin, it has no oral preparation for systemic infections.

The main side effect of tigecycline is nausea.61 Other reported issues include pancreatitis and extreme alkaline phosphatase elevations.

The efficacy of tigecycline has come into question in view of meta-analyses of clinical trials, some of which have shown higher mortality rates in patients treated with tigecycline than with comparator agents.62–65 Based on these data, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a warning in 2010 regarding the increased mortality risk. Although these meta-analyses did not include patients with CRE for whom available comparators would have been ineffective, it is an important safety signal.

The efficacy of tigecycline is further limited by increasing in vitro resistance in CRE. Serum and urinary levels of tigecycline are low, and most experts discourage the use of tigecycline as monotherapy for blood stream or urinary tract infections.

Aminoglycosides

CRE display variable in vitro susceptibility to different aminoglycosides. If the organism is susceptible, aminoglycosides may be very useful in the treatment of CRE infections, especially urinary tract infectons. In a study of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae urinary tract infections, patients who were treated with polymyxins or tigecycline were significantly less likely to have clearance of their urine as compared with patients treated with aminoglycosides.66

Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are demonstrated adverse effects of aminoglycosides. Close monitoring of serum levels, interval audiology examinations at baseline and during therapy, and the use of extended-interval dosing may help to decrease the incidence of these toxicities.

Fosfomycin

Fosfomycin is only available as an oral formulation in the United States, although intravenous administration has been used in other countries. It is exclusively used to treat urinary tract infections.

CRE often retain susceptibility to fosfomycin, and clearance of urine in cystitis may be attempted with this agent to avoid the need for intravenous treatment.29,67

Combination therapy, other topics to be explored

Recent observational reports from Greece, Italy, and the United States describe higher survival rates in patients with CRE infections treated with a combination regimen rather than monotherapy with colistin or tigecycline. This is despite reliable activity of colistin and tigecycline, and often in regimens containing carbapenems. Clinical experiments are needed to clarify the value of combination regimens that include carbapenems for the treatment of CRE infections.

Similarly, the role of carbapenems given as a high-dose prolonged infusion or as double carbapenem therapy needs to be explored further.37,55,56,68

Also to be determined is the optimal duration of treatment. To date, there is no evidence that increasing the duration of treatment beyond that recommended for infections with more susceptible bacteria results in improved outcomes. Therefore, commonly used durations include 1 week for complicated urinary tract infections, 2 weeks for bacteremia (from the first day with negative blood cultures and source control), and 8 to 14 days for pneumonia.

A SERIOUS THREAT

The emergence of CRE is a serious threat to the safety of patients in our health care system. CRE are highly successful nosocomial pathogens selected by the use of antibiotics, which burden patients debilitated by advanced age, comorbidities, and medical interventions. Infections with CRE result in poor outcomes, and available treatments of last resort such as tigecycline and colistin are of unclear efficacy and safety.

Control of CRE transmission is hindered by the transit of patients through long-term care facilities, and detection of CRE is difficult because of the myriad mechanisms involved and the imperfect methods currently available. Clinicians are concerned and frustrated, especially given the paucity of antibiotics in development to address the therapeutic dilemma posed by CRE. The challenge of CRE and other multidrug-resistant organisms requires the concerted response of professionals in various disciplines, including pharmacists, microbiologists, infection control practitioners, and infectious disease clinicians (Table 2).

Control of transmission by infection prevention strategies and by antimicrobial stewardship is going to be crucial in the years to come, not only for limiting the spread of CRE, but also for preventing the next multidrug-resistant “superbug” from emerging. However, the current reality is that health care providers will be faced with increased numbers of patients infected with CRE.

Prospective studies into transmission, molecular characteristics, and, most of all, treatment regimens are urgently needed. In addition, the development of new antimicrobials and nontraditional antimicrobial methods should have international priority.

- Papp-Wallace KM, Endimiani A, Taracila MA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenems: past, present, and future. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:4943–4960.

- Rahal JJ, Urban C, Horn D, et al. Class restriction of cephalosporin use to control total cephalosporin resistance in nosocomial Klebsiella. JAMA 1998; 280:1233–1237.

- Paterson DL, Ko WC, Von Gottberg A, et al. International prospective study of Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia: implications of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase production in nosocomial Infections. Ann Intern Med 2004; 140:26–32.

- Endimiani A, Luzzaro F, Perilli M, et al. Bacteremia due to Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates producing the TEM-52 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase: treatment outcome of patients receiving imipenem or ciprofoxacin. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:243–251.

- Livermore DM, Sefton AM, Scott GM. Properties and potential of ertapenem. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003; 52:331–344.

- Bazan JA, Martin SI, Kaye KM. Newer beta-lactam antibiotics: doripenem, ceftobiprole, ceftaroline, and cefepime. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009; 23:983–996, ix.

- Pakyz AL, MacDougall C, Oinonen M, Polk RE. Trends in antibacterial use in US academic health centers: 2002 to 2006. Arch Intern Med 2008; 168:2254–2260.

- Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2013; 34:1–14.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. MMWR 2013; 62:165–170.

- Yigit H, Queenan AM, Anderson GJ, et al. Novel carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase, KPC-1, from a carbapenem-resistant strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2001; 45:1151–1161.

- Smith Moland E, Hanson ND, Herrera VL, et al. Plasmid-mediated, carbapenem-hydrolysing beta-lactamase, KPC-2, in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother 2003; 51:711–714.

- Woodford N, Tierno PM, Young K, et al. Outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing a new carbapenem-hydrolyzing class A beta-lactamase, KPC-3, in a New York medical center. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2004; 48:4793–4799.

- Lehey Clinic. OXA-type β-Lactamases. http://www.lahey.org/Studies/other.asp#table1. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- Mathers AJ, Cox HL, Kitchel B, et al. Molecular dissection of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae reveals intergenus KPC carbapenemase transmission through a promiscuous plasmid. MBio 2011; 2 6:e00204–11.

- Endimiani A, Hujer AM, Perez F, et al. Characterization of blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates detected in different institutions in the Eastern USA. J Antimicrob Chemother 2009; 63:427–437.

- Endimiani A, Carias LL, Hujer AM, et al. Presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates possessing blaKPC in the United States. Antimicro Agents Chemother 2008; 52:2680–2682.

- Magiorakos A P, Srinivasan A, Carey RB, et al. Multidrug-resistant, extensively drug-resistant and pandrug-resistant bacteria: an international expert proposal for interim standard definitions for acquired resistance. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18:268–281.

- Tzouvelekis LS, Markogiannakis A, Psichogiou M, Tassios PT, Daikos GL. Carbapenemases in Klebsiella pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae: an evolving crisis of global dimensions. Clin Microbiol Rev 2012; 25:682–707.

- Lopez JA, Correa A, Navon-Venezia S, et al. Intercontinental spread from Israel to Colombia of a KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strain. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:52–56.

- Naas T, Nordmann P, Vedel G, Poyart C. Plasmid-mediated carbapenem-hydrolyzing beta-lactamase KPC in a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate from France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2005; 49:4423–4424.

- Navon-Venezia S, Leavitt A, Schwaber MJ, et al. First report on a hyperepidemic clone of KPC-3-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Israel genetically related to a strain causing outbreaks in the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:818–820.

- Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-beta-lactamase gene, bla(NDM-1), and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:5046–5054.

- Livermore DM, Walsh TR, Toleman M, Woodford N. Balkan NDM-1: escape or transplant? Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:164.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae containing New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase in two patients - Rhode Island, March 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2012Jun 22; 61:446–448.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Detection of Enterobacteriaceae isolates carrying metallo-beta-lactamase—United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2010; 59:750.

- McGann P, Hang J, Clifford RJ, et al. Complete sequence of a novel 178-kilobase plasmid carrying bla(NDM-1) in a Providencia stuartii strain isolated in Afghanistan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:1673–1679.

- Borgia S, Lastovetska O, Richardson D, et al. Outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing blaNDM-1, Ontario, Canada. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:e109–e117.

- Endimiani A, Perez F, Bajaksouzian S, et al. Evaluation of updated interpretative criteria for categorizing Klebsiella pneumoniae with reduced carbapenem susceptibility. J Clinic Microbiol 2010; 48:4417–4425.

- Neuner EA, Sekeres J, Hall GS, van Duin D. Experience with fosfomycin for treatment of urinary tract infections due to multidrug-resistant organisms. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:5744–5748.

- Neuner EA, Yeh JY, Hall GS, et al. Treatment and outcomes in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Diagnostic Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 69:357–362.

- van Duin D, Kaye KS, Neuner EA, Bonomo RA. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: a review of treatment and outcomes. Diagnostic Microbiol Infect Dis 2013; 75:115–120.

- Neuner EA, Yeh J-Y, Hall GS, et al. Treatment and outcomes in carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infections. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2011; 69:357–362.

- Patel G, Huprikar S, Factor SH, Jenkins SG, Calfee DP. Outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection and the impact of antimicrobial and adjunctive therapies. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29:1099–1106.

- Borer A, Saidel-Odes L, Riesenberg K, et al. Attributable mortality rate for carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2009; 30:972–976.

- Marchaim D, Chopra T, Perez F, et al. Outcomes and genetic relatedness of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae at Detroit medical center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32:861–871.

- Perez F, Endimiani A, Ray AJ, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Klebsiella pneumoniae across a hospital system: impact of post-acute care facilities on dissemination. J Antimicrob Chemother 2010; 65:1807–1818.

- Tumbarello M, Viale P, Viscoli C, et al. Predictors of mortality in bloodstream infections caused by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae: importance of combination therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:943–950.

- Little ML, Qin X, Zerr DM, Weissman SJ. Molecular diversity in mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in paediatric Enterobacteriaceae. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 39:52–57.

- Logan LK. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging problem in children. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55:852–859.

- Rastegar Lari A, Azimi L, Rahbar M, Fallah F, Alaghehbandan R. Phenotypic detection of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase among burns patients: first report from Iran. Burns 2013; 39:174–176.

- Zarkotou O, Pournaras S, Tselioti P, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with bloodstream infections caused by KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae and impact of appropriate antimicrobial treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:1798–1803.

- Hyle EP, Ferraro MJ, Silver M, Lee H, Hooper DC. Ertapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: risk factors for acquisition and outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:1242–1249.

- Ben-David D, Masarwa S, Navon-Venezia S, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in post-acute-care facilities in Israel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2011; 32:845–853.

- Safdar N, Maki DG. The commonality of risk factors for nosocomial colonization and infection with antimicrobial-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, enterococcus, gram-negative bacilli, Clostridium difficile, and Candida. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:834–844.

- Marchaim D, Perez F, Lee J, et al. “Swimming in resistance”: co-colonization with carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae and Acinetobacter baumannii or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.” Am J Infect Control 2012; 40:830–835.

- Smith PW, Bennett G, Bradley S, et al. SHEA/APIC Guideline: Infection prevention and control in the long-term care facility. Am J Infect Control 2008; 36:504–535.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for control of infections with carbapenem-resistant or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in acute care facilities. MMWR 2009; 58:256–260.

- Munoz-Price LS, De La Cuesta C, Adams S, et al. Successful eradication of a monoclonal strain of Klebsiella pneumoniae during a K. pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae outbreak in a surgical intensive care unit in Miami, Florida. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2010; 31:1074–1077.

- Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Thomas PJ, et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with wholegenome sequencing. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4:148ra16.

- Srinivasan A, Patel JB. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing organisms: an ounce of prevention really is worth a pound of cure. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2008; 29:1107–1109.

- Viau RA, Hujer AM, Marshall SH, et al. “Silent” dissemination of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates bearing K pneumoniae carbapenemase in a long-term care facility for children and young adults in Northeast Ohio”. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1314–1321.

- Galani I, Rekatsina PD, Hatzaki D, Plachouras D, Souli M, Giamarellou H. Evaluation of different laboratory tests for the detection of metallo-beta-lactamase production in Enterobacteriaceae. J Antimicrob Chemother 2008; 61:548–553.

- Anderson KF, Lonsway DR, Rasheed JK, et al. Evaluation of methods to identify the Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase in Enterobacteriaceae. J Clin Microbiol 2007; 45:2723–2725.

- Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, Rice JC, Schaeffer A, Hooton TM. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2005; 40:643–654.

- Daikos GL, Markogiannakis A. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: (when) might we still consider treating with carbapenems? Clin Microbiol Infect 2011; 17:1135–1141.

- Bulik CC, Nicolau DP. Double-carbapenem therapy for carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:3002–3004.

- Pogue JM, Lee J, Marchaim D, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for colistin-associated nephrotoxicity in a large academic health system. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53:879–884.

- Garonzik SM, Li J, Thamlikitkul V, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulfonate and formed colistin in critically ill patients from a multicenter study provide dosing suggestions for various categories of patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:3284–3294.

- Dalfno L, Puntillo F, Mosca A, et al. High-dose, extended-interval colistin administration in critically ill patients: is this the right dosing strategy? A preliminary study. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1720–1726.

- Marchaim D, Chopra T, Pogue JM, et al. Outbreak of colistin-resistant, carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in metropolitan Detroit, Michigan. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:593–599.

- Bonilla MF, Avery RK, Rehm SJ, Neuner EA, Isada CM, van Duin D. Extreme alkaline phosphatase elevation associated with tigecycline. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66:952–953.

- Prasad P, Sun J, Danner RL, Natanson C. Excess deaths associated with tigecycline after approval based on noninferiority trials. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 54:1699–1709.

- Tasina E, Haidich AB, Kokkali S, Arvanitidou M. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline for the treatment of infectious diseases: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis 2011; 11:834–844.

- Cai Y, Wang R, Liang B, Bai N, Liu Y. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and safety of tigecycline for treatment of infectious disease. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:1162–1172.

- Yahav D, Lador A, Paul M, Leibovici L. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 2011; 66:1963–1971.

- Satlin MJ, Kubin CJ, Blumenthal JS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of aminoglycosides, polymyxin B, and tigecycline for clearance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from urine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55:5893–5899.

- Endimiani A, Patel G, Hujer KM, et al. In vitro activity of fosfomycin against blaKPC-containing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates, including those nonsusceptible to tigecycline and/or colistin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54:526–529.

- Qureshi ZA, Paterson DL, Potoski BA, et al. Treatment outcome of bacteremia due to KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: superiority of combination antimicrobial regimens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56:2108–2113.

The past 10 years have brought a formidable challenge to the clinical arena, as carbapenems, until now the most reliable antibiotics against Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli, and other Enterobacteriaceae, are becoming increasingly ineffective.

Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) pose a serious threat to hospitalized patients. Moreover, CRE often demonstrate resistance to many other classes of antibiotics, thus limiting our therapeutic options. Furthermore, few new antibiotics are in line to replace carbapenems. This public health crisis demands redefined and refocused efforts in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of infections in hospitalized patients.

Here, we present an overview of CRE and discuss avenues to escape a new era of untreatable infections.

INCREASED USE OF CARBAPENEMS AND EMERGENCE OF RESISTANCE

Developed in the 1980s, carbapenems are derivatives of thyanamycin. Imipenem and meropenem, the first members of the class, had a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity that included coverage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, adequately positioning them for the treatment of nosocomial infections. Back then, nearly all Enterobacteriaceae were susceptible to carbapenems.1

In the 1990s, Enterobacteriaceae started to develop resistance to cephalosporins—till then, the first-line antibiotics for these organisms—by acquiring extended-spectrum betalactamases, which inactivate those agents. Consequently, the use of cephalosporins had to be restricted, while carbapenems, which remained impervious to these enzymes, had to be used more.2 In pivotal international studies in the treatment of infections caused by strains of K pneumoniae that produced these inactivating enzymes, outcomes were better with carbapenems than with cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.3,4

Ertapenem, a carbapenem without antipseudomonal activity and highly bound to protein, was released in 2001. Its prolonged half-life permitted once-daily dosing, which positioned it as an option for treating infections in community dwellers.5 Doripenem is the newest member of the class of carbapenems, and its spectrum of activity is similar to that of imipenem and meropenem and includes P aeruginosa.6 The use of carbapenems, measured in a representative sample of 35 university hospitals in the United States, increased by 59% between 2002 and 2006.7

In the early 2000s, carbapenem resistance in K pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae was rare in North America. But then, after initial outbreaks occurred in hospitals in the Northeast (especially New York City), CRE began to spread throughout the United States. By 2009–2010, the National Healthcare Safety Network from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that 12.8% of K pneumoniae isolates associated with bloodstream infections were resistant to carbapenems.8

In March 2013, the CDC disclosed that 3.9% of short-stay acute-care hospitals and 17.8% of long-term acute-care hospitals reported at least one CRE health care-associated infection in 2012. CRE had extended to 42 states, and the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae that are CRE had increased fourfold over the past 10 years.9

Coinciding with the increased use of carbapenems, multiple factors and modifiers likely contributed to the dramatic increase in CRE. These include use of other antibiotics in humans and animals, their relative penetration and selective effect on the gut microbiota, case-mix and infection control practices in different health care settings, and travel patterns.

POWERFUL ENZYMES THAT TRAVEL FAR

Bacterial acquisition of carbapenemases, enzymes that inactivate carbapenems, is crucial to the emergence of CRE. The enzyme in the sentinel carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae isolate found in 1996 in North Carolina was designated K pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-1). This mechanism also conferred resistance to all cephalosporins, aztreonam, and beta-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid and tazobactam.10

KPC-2 (later determined to be identical to KPC-1) was found in K pneumoniae from Baltimore, and KPC-3 caused an early outbreak in New York City.11,12 To date, 12 additional variants of blaKPC, the gene encoding for the KPC enzyme, have been described.13

The genes encoding carbapenemases are usually found on plasmids or other common mobile genetic elements.14 These genetic elements allow the organism to acquire genes conferring resistance to other classes of antimicrobials, such as aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and fluoroquinolone-resistance determinants, and beta-lactamases.15,16 The result is that CRE isolates are increasingly multidrug-resistant (ie, resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials), extensively drug-resistant (ie, resistant to all but one or two classes), or pandrug-resistant (ie, resistant to all available classes of antibiotics).17 Thus, up to 98% of KPC-producing K pneumoniae are resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 90% are resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 60% are resistant to gentamicin or amikacin.15

The mobility of these genetic elements has also allowed for dispersion into diverse Enterobacteriaceae such as E coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Salmonella species. Furthermore, KPC has been described in non-Enterobacteriaceae such as Acinetobacter baumannii and P aeruginosa.

Extending globally, KPC is now endemic in the Mediterranean basin, including Israel, Greece, and Italy; in South America, especially Colombia, Argentina, and Brazil; and in China.18 Most interesting is the intercontinental transfer of these strains: it has been documented that the index patient with KPC-producing K pneumoniae in Medellin, Colombia, came from Israel to undergo liver transplantation.19 Likewise, KPC-producing K pneumoniae in France and Israel could be linked epidemiologically and genetically to the predominant US strain.20,21

Even more explosive has been the surge of another carbapenemase, the Ambler Class B New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM-1. Initially reported in a urinary isolate of K pneumoniae from a Swedish patient who had been hospitalized in New Delhi in 2008, NDM-1 was soon found throughout India, in Pakistan, and in the United Kingdom.22 Interestingly, several of the UK patients with NDM-1-harboring bacteria had received organ transplants in the Indian subcontinent. Reports from elsewhere in Europe, Australia, and Africa followed suit, usually with a connection to the Indian subcontinent epicenter. In contrast, several other cases in Europe were traced to the Balkans, where there appears to be another focus of NDM-1.23

Penetration of NDM-1 into North America has begun, with cases and outbreaks reported in several US and Canadian regions, and in a military medical facility in Afghanistan. In several of these instances, there has been a documented link with travel and hospitalizations overseas.24–27 However, no such link with travel could be established in a recent outbreak in Ontario.27

In addition, resistance to carbapenems may result from other enzymes (Table 1), or from combinations of changes in outer membrane porins and the production of extended spectrum beta-lactamases or other cephalosporinases.28

DEADLY IMPACT ON THE MOST VULNERABLE

Regardless of the resistance pattern, Enterobacteriaceae are an important cause of health care-associated infections, including urinary and bloodstream infections in patients with indwelling catheters, pneumonia (often in association with mechanical ventilation), and, less frequently, infections of skin and soft tissues and the central nervous system.29–31

Several studies have examined the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with CRE infections. Those typically affected are elderly and debilitated and have multiple comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression. They are heavily exposed to health care with frequent antecedent hospitalizations and invasive procedures. Furthermore, they are often severely ill and require intensive care. Patients infected with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae, compared with those with carbapenem-susceptible strains, are more likely to have undergone organ or stem cell transplantation or mechanical ventilation, and to have had a longer hospital stay before infection.

They also experience a high mortality rate, which ranges from 30% in patients with nonbacteremic infections to 72% in series of patients with liver transplants or bloodstream infections.32–37

More recently, CRE has been reported in other vulnerable populations, such as children with critical illness or cancer and in burn patients.38–40

Elderly and critically ill patients with bacteremia originating from a high-risk source (eg, pneumonia) typically face the most adverse outcomes. With increasing drug resistance, inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy is more commonly seen and may account for some of these poor outcomes.37,41

LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES IN THE EYE OF THE STORM

A growing body of evidence suggests that long-term care facilities play a crucial role in the spread of CRE.

In an investigation into carbapenem-resistant A baumanii and K pneumoniae in a hospital system,36 75% of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae were admitted from long-term care facilities, and only 1 of 13 patients was discharged home.

In a series of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae bloodstream infections, 42% survived their index hospital stay. Of these patients, only 32% were discharged home, and readmissions were very common.32

Admission from a long-term care facility or transfer from another hospital is significantly associated with carbapenem resistance in patients with Enterobacteriaceae.42 Similarly, in Israel, a large reservoir of CRE was found in postacute care facilities.43

It is clear that long-term care residents are at increased risk of colonization and infection with CRE. However, further studies are needed to evaluate whether this simply refects an overlap in risk factors, or whether significant patient-to-patient transmission occurs in these settings.

INFECTION CONTROL TAKES CENTER STAGE

It is important to note that risk factors for CRE match those of various nosocomial infections, including other resistant gram-negative bacilli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Candida species, and Clostridium difficile; in fact, CRE often coexist with other multidrug-resistant organisms.44,45

Common risk factors include residence in a long-term care facility, an intensive care unit stay, use of lines and catheters, and antibiotic exposure. This commonality of risk factors implies that systematic infection-prevention measures will have an impact on the prevalence and incidence rates of multidrug-resistant organism infections across the board, CRE included. It should be emphasized that strict compliance with hand hygiene is still the foundation of any infection-prevention strategy.

Infection prevention and the control of transmission of CRE in long-term care facilities pose unique challenges. Guidelines from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control recommend the use of contact precautions for patients with multidrug-resistant organisms, including CRE, who are ill and totally dependent on health care workers for activities of daily living or whose secretions or drainage cannot be contained. These same guidelines advise against attempting to eradicate multidrug-resistant organism colonization status.46

In acute care facilities, Best Infection Control Practices from the CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee encourage mechanisms for the rapid recognition and reporting of CRE cases to infection prevention personnel so that contact precautions can be implemented. Furthermore, facilities without CRE cases should carry out periodic laboratory reviews to identify cases, and patients exposed to CRE cases should be screened with surveillance cultures.47

Outbreaks of CRE may require extraordinary infection control measures. An approach combining point-prevalence surveillance of colonization, detection of environmental and common-equipment contamination, with the implementation of a bundle consisting of chlorhexidine baths, cohorting of colonized patients and health care personnel, increased environmental cleaning, and staff education may be effective in controlling outbreaks of CRE.48

Nevertheless, control of CRE may prove exceptionally difficult. A recent high-profile outbreak of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Maryland caused infections in 18 patients, 11 of whom died.49 Of note, carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected in this outbreak in both respiratory equipment and sink drains. The outbreak was ultimately contained by detection through surveillance cultures and by strict cohorting of colonized patients, which minimized common medical equipment and personnel between affected patients and other patients in the hospital. Additionally, rooms were sanitized with hydrogen peroxide vapor, and sinks and drains where carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected were removed.

CHALLENGES IN THE MICROBIOLOGY LABORATORY

Adequate treatment and control of CRE infections is predicated upon their accurate and prompt diagnosis from patient samples in the clinical microbiology laboratory.50

Traditional and current culture-based methods take several days to provide that information, delaying effective antibiotic therapy and permitting the transmission of undetected CRE. Furthermore, interpretative criteria of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of carbapenems recently required readjustment, as many KPC-producing strains of K pneumoniae had MICs below the previous breakpoint of resistance. In the past, this contributed to instances of “silent” dissemination of KPC-producing K pneumoniae.51

In contrast, using the new lower breakpoints of resistance for carbapenems without using a phenotypic test such as the modified Hodge test or the carbapenem-EDTA combination tests will result in a lack of differentiation between various mechanisms of carbapenem resistance.28,52,53 This may be clinically relevant, as the clinical response to carbapenem therapy may vary depending on the mechanism of resistance.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES APPLY

In treating patients infected with CRE, clinicians need to strictly observe general principles of infectious disease management to ensure the best possible outcomes. These include:

Timely and accurate diagnosis, as discussed above.

Source control, which should include drainage of any infected collections, and removal of lines, devices, and urinary catheters.

Distinguishing between infection and colonization. CRE are often encountered as urinary isolates, and the distinction between asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection may be extremely difficult, especially in residents of long-term care facilities with chronic indwelling catheters, who are thegroup at highest risk of CRE colonization and infection. Urinalysis may be helpful in the absence of pyuria, as this rules out an infection; however, it must be emphasized that the presence of pyuria is not a helpful feature, as pyuria is common in both asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection.54 Symptoms should be carefully evaluated in every patient with bacteriuria, and urinary tract infection should be a diagnosis of exclusion in patients with functional symptoms such as confusion or falls.

Selection of the most appropriate antibiotic regimen. While the emphasis is often on the antibiotic regimen, the above elements should not be neglected.

A DWINDLING THERAPEUTIC ARSENAL

Clinicians treating CRE infections are left with only a few antibiotic options. These options are generally limited by a lack of clinical data on efficacy, as well as by concerns about toxicity. These “drugs of last resort” include polymyxins (such as colistin), aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and fosfomycin. The role of carbapenem therapy, potentially in combination regimens, in a high-dose prolonged infusion, or even “double carbapenem therapy” remains to be determined.37,55,56

Colistin

Colistin is one of the first-line agents for treating CRE infections. First introduced in the 1950s, its use was mostly abandoned in favor of aminoglycosides. A proportion of the data on safety and efficacy of colistin, therefore, is based on older, less rigorous studies.

Neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity are the two main concerns with colistin, and while the incidence of these adverse events does appear to be lower with modern preparations, it is still substantial.57 Dosing issues have not been completely clarified either, especially in relation to renal clearance and in patients on renal replacement therapy.58,59 Unfortunately, there have been reports of outbreaks of CRE displaying resistance to colistin.60

Tigecycline

Tigecycline is a newer antibiotic of the glycylcycline class. Like colistin, it has no oral preparation for systemic infections.

The main side effect of tigecycline is nausea.61 Other reported issues include pancreatitis and extreme alkaline phosphatase elevations.

The efficacy of tigecycline has come into question in view of meta-analyses of clinical trials, some of which have shown higher mortality rates in patients treated with tigecycline than with comparator agents.62–65 Based on these data, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a warning in 2010 regarding the increased mortality risk. Although these meta-analyses did not include patients with CRE for whom available comparators would have been ineffective, it is an important safety signal.

The efficacy of tigecycline is further limited by increasing in vitro resistance in CRE. Serum and urinary levels of tigecycline are low, and most experts discourage the use of tigecycline as monotherapy for blood stream or urinary tract infections.

Aminoglycosides

CRE display variable in vitro susceptibility to different aminoglycosides. If the organism is susceptible, aminoglycosides may be very useful in the treatment of CRE infections, especially urinary tract infectons. In a study of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae urinary tract infections, patients who were treated with polymyxins or tigecycline were significantly less likely to have clearance of their urine as compared with patients treated with aminoglycosides.66

Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are demonstrated adverse effects of aminoglycosides. Close monitoring of serum levels, interval audiology examinations at baseline and during therapy, and the use of extended-interval dosing may help to decrease the incidence of these toxicities.

Fosfomycin

Fosfomycin is only available as an oral formulation in the United States, although intravenous administration has been used in other countries. It is exclusively used to treat urinary tract infections.

CRE often retain susceptibility to fosfomycin, and clearance of urine in cystitis may be attempted with this agent to avoid the need for intravenous treatment.29,67

Combination therapy, other topics to be explored

Recent observational reports from Greece, Italy, and the United States describe higher survival rates in patients with CRE infections treated with a combination regimen rather than monotherapy with colistin or tigecycline. This is despite reliable activity of colistin and tigecycline, and often in regimens containing carbapenems. Clinical experiments are needed to clarify the value of combination regimens that include carbapenems for the treatment of CRE infections.

Similarly, the role of carbapenems given as a high-dose prolonged infusion or as double carbapenem therapy needs to be explored further.37,55,56,68

Also to be determined is the optimal duration of treatment. To date, there is no evidence that increasing the duration of treatment beyond that recommended for infections with more susceptible bacteria results in improved outcomes. Therefore, commonly used durations include 1 week for complicated urinary tract infections, 2 weeks for bacteremia (from the first day with negative blood cultures and source control), and 8 to 14 days for pneumonia.

A SERIOUS THREAT

The emergence of CRE is a serious threat to the safety of patients in our health care system. CRE are highly successful nosocomial pathogens selected by the use of antibiotics, which burden patients debilitated by advanced age, comorbidities, and medical interventions. Infections with CRE result in poor outcomes, and available treatments of last resort such as tigecycline and colistin are of unclear efficacy and safety.

Control of CRE transmission is hindered by the transit of patients through long-term care facilities, and detection of CRE is difficult because of the myriad mechanisms involved and the imperfect methods currently available. Clinicians are concerned and frustrated, especially given the paucity of antibiotics in development to address the therapeutic dilemma posed by CRE. The challenge of CRE and other multidrug-resistant organisms requires the concerted response of professionals in various disciplines, including pharmacists, microbiologists, infection control practitioners, and infectious disease clinicians (Table 2).

Control of transmission by infection prevention strategies and by antimicrobial stewardship is going to be crucial in the years to come, not only for limiting the spread of CRE, but also for preventing the next multidrug-resistant “superbug” from emerging. However, the current reality is that health care providers will be faced with increased numbers of patients infected with CRE.

Prospective studies into transmission, molecular characteristics, and, most of all, treatment regimens are urgently needed. In addition, the development of new antimicrobials and nontraditional antimicrobial methods should have international priority.

The past 10 years have brought a formidable challenge to the clinical arena, as carbapenems, until now the most reliable antibiotics against Klebsiella species, Escherichia coli, and other Enterobacteriaceae, are becoming increasingly ineffective.

Infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) pose a serious threat to hospitalized patients. Moreover, CRE often demonstrate resistance to many other classes of antibiotics, thus limiting our therapeutic options. Furthermore, few new antibiotics are in line to replace carbapenems. This public health crisis demands redefined and refocused efforts in the diagnosis, treatment, and control of infections in hospitalized patients.

Here, we present an overview of CRE and discuss avenues to escape a new era of untreatable infections.

INCREASED USE OF CARBAPENEMS AND EMERGENCE OF RESISTANCE

Developed in the 1980s, carbapenems are derivatives of thyanamycin. Imipenem and meropenem, the first members of the class, had a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity that included coverage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, adequately positioning them for the treatment of nosocomial infections. Back then, nearly all Enterobacteriaceae were susceptible to carbapenems.1

In the 1990s, Enterobacteriaceae started to develop resistance to cephalosporins—till then, the first-line antibiotics for these organisms—by acquiring extended-spectrum betalactamases, which inactivate those agents. Consequently, the use of cephalosporins had to be restricted, while carbapenems, which remained impervious to these enzymes, had to be used more.2 In pivotal international studies in the treatment of infections caused by strains of K pneumoniae that produced these inactivating enzymes, outcomes were better with carbapenems than with cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.3,4

Ertapenem, a carbapenem without antipseudomonal activity and highly bound to protein, was released in 2001. Its prolonged half-life permitted once-daily dosing, which positioned it as an option for treating infections in community dwellers.5 Doripenem is the newest member of the class of carbapenems, and its spectrum of activity is similar to that of imipenem and meropenem and includes P aeruginosa.6 The use of carbapenems, measured in a representative sample of 35 university hospitals in the United States, increased by 59% between 2002 and 2006.7

In the early 2000s, carbapenem resistance in K pneumoniae and other Enterobacteriaceae was rare in North America. But then, after initial outbreaks occurred in hospitals in the Northeast (especially New York City), CRE began to spread throughout the United States. By 2009–2010, the National Healthcare Safety Network from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) revealed that 12.8% of K pneumoniae isolates associated with bloodstream infections were resistant to carbapenems.8

In March 2013, the CDC disclosed that 3.9% of short-stay acute-care hospitals and 17.8% of long-term acute-care hospitals reported at least one CRE health care-associated infection in 2012. CRE had extended to 42 states, and the proportion of Enterobacteriaceae that are CRE had increased fourfold over the past 10 years.9

Coinciding with the increased use of carbapenems, multiple factors and modifiers likely contributed to the dramatic increase in CRE. These include use of other antibiotics in humans and animals, their relative penetration and selective effect on the gut microbiota, case-mix and infection control practices in different health care settings, and travel patterns.

POWERFUL ENZYMES THAT TRAVEL FAR

Bacterial acquisition of carbapenemases, enzymes that inactivate carbapenems, is crucial to the emergence of CRE. The enzyme in the sentinel carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae isolate found in 1996 in North Carolina was designated K pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC-1). This mechanism also conferred resistance to all cephalosporins, aztreonam, and beta-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid and tazobactam.10

KPC-2 (later determined to be identical to KPC-1) was found in K pneumoniae from Baltimore, and KPC-3 caused an early outbreak in New York City.11,12 To date, 12 additional variants of blaKPC, the gene encoding for the KPC enzyme, have been described.13

The genes encoding carbapenemases are usually found on plasmids or other common mobile genetic elements.14 These genetic elements allow the organism to acquire genes conferring resistance to other classes of antimicrobials, such as aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes and fluoroquinolone-resistance determinants, and beta-lactamases.15,16 The result is that CRE isolates are increasingly multidrug-resistant (ie, resistant to three or more classes of antimicrobials), extensively drug-resistant (ie, resistant to all but one or two classes), or pandrug-resistant (ie, resistant to all available classes of antibiotics).17 Thus, up to 98% of KPC-producing K pneumoniae are resistant to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 90% are resistant to fluoroquinolones, and 60% are resistant to gentamicin or amikacin.15

The mobility of these genetic elements has also allowed for dispersion into diverse Enterobacteriaceae such as E coli, Klebsiella oxytoca, Enterobacter, Serratia, and Salmonella species. Furthermore, KPC has been described in non-Enterobacteriaceae such as Acinetobacter baumannii and P aeruginosa.

Extending globally, KPC is now endemic in the Mediterranean basin, including Israel, Greece, and Italy; in South America, especially Colombia, Argentina, and Brazil; and in China.18 Most interesting is the intercontinental transfer of these strains: it has been documented that the index patient with KPC-producing K pneumoniae in Medellin, Colombia, came from Israel to undergo liver transplantation.19 Likewise, KPC-producing K pneumoniae in France and Israel could be linked epidemiologically and genetically to the predominant US strain.20,21

Even more explosive has been the surge of another carbapenemase, the Ambler Class B New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase, or NDM-1. Initially reported in a urinary isolate of K pneumoniae from a Swedish patient who had been hospitalized in New Delhi in 2008, NDM-1 was soon found throughout India, in Pakistan, and in the United Kingdom.22 Interestingly, several of the UK patients with NDM-1-harboring bacteria had received organ transplants in the Indian subcontinent. Reports from elsewhere in Europe, Australia, and Africa followed suit, usually with a connection to the Indian subcontinent epicenter. In contrast, several other cases in Europe were traced to the Balkans, where there appears to be another focus of NDM-1.23

Penetration of NDM-1 into North America has begun, with cases and outbreaks reported in several US and Canadian regions, and in a military medical facility in Afghanistan. In several of these instances, there has been a documented link with travel and hospitalizations overseas.24–27 However, no such link with travel could be established in a recent outbreak in Ontario.27

In addition, resistance to carbapenems may result from other enzymes (Table 1), or from combinations of changes in outer membrane porins and the production of extended spectrum beta-lactamases or other cephalosporinases.28

DEADLY IMPACT ON THE MOST VULNERABLE

Regardless of the resistance pattern, Enterobacteriaceae are an important cause of health care-associated infections, including urinary and bloodstream infections in patients with indwelling catheters, pneumonia (often in association with mechanical ventilation), and, less frequently, infections of skin and soft tissues and the central nervous system.29–31

Several studies have examined the clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients with CRE infections. Those typically affected are elderly and debilitated and have multiple comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus and immunosuppression. They are heavily exposed to health care with frequent antecedent hospitalizations and invasive procedures. Furthermore, they are often severely ill and require intensive care. Patients infected with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae, compared with those with carbapenem-susceptible strains, are more likely to have undergone organ or stem cell transplantation or mechanical ventilation, and to have had a longer hospital stay before infection.

They also experience a high mortality rate, which ranges from 30% in patients with nonbacteremic infections to 72% in series of patients with liver transplants or bloodstream infections.32–37

More recently, CRE has been reported in other vulnerable populations, such as children with critical illness or cancer and in burn patients.38–40

Elderly and critically ill patients with bacteremia originating from a high-risk source (eg, pneumonia) typically face the most adverse outcomes. With increasing drug resistance, inadequate initial antimicrobial therapy is more commonly seen and may account for some of these poor outcomes.37,41

LONG-TERM CARE FACILITIES IN THE EYE OF THE STORM

A growing body of evidence suggests that long-term care facilities play a crucial role in the spread of CRE.

In an investigation into carbapenem-resistant A baumanii and K pneumoniae in a hospital system,36 75% of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae were admitted from long-term care facilities, and only 1 of 13 patients was discharged home.

In a series of patients with carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae bloodstream infections, 42% survived their index hospital stay. Of these patients, only 32% were discharged home, and readmissions were very common.32

Admission from a long-term care facility or transfer from another hospital is significantly associated with carbapenem resistance in patients with Enterobacteriaceae.42 Similarly, in Israel, a large reservoir of CRE was found in postacute care facilities.43

It is clear that long-term care residents are at increased risk of colonization and infection with CRE. However, further studies are needed to evaluate whether this simply refects an overlap in risk factors, or whether significant patient-to-patient transmission occurs in these settings.

INFECTION CONTROL TAKES CENTER STAGE

It is important to note that risk factors for CRE match those of various nosocomial infections, including other resistant gram-negative bacilli, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Candida species, and Clostridium difficile; in fact, CRE often coexist with other multidrug-resistant organisms.44,45

Common risk factors include residence in a long-term care facility, an intensive care unit stay, use of lines and catheters, and antibiotic exposure. This commonality of risk factors implies that systematic infection-prevention measures will have an impact on the prevalence and incidence rates of multidrug-resistant organism infections across the board, CRE included. It should be emphasized that strict compliance with hand hygiene is still the foundation of any infection-prevention strategy.

Infection prevention and the control of transmission of CRE in long-term care facilities pose unique challenges. Guidelines from the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology and the Association for Professionals in Infection Control recommend the use of contact precautions for patients with multidrug-resistant organisms, including CRE, who are ill and totally dependent on health care workers for activities of daily living or whose secretions or drainage cannot be contained. These same guidelines advise against attempting to eradicate multidrug-resistant organism colonization status.46

In acute care facilities, Best Infection Control Practices from the CDC and the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee encourage mechanisms for the rapid recognition and reporting of CRE cases to infection prevention personnel so that contact precautions can be implemented. Furthermore, facilities without CRE cases should carry out periodic laboratory reviews to identify cases, and patients exposed to CRE cases should be screened with surveillance cultures.47

Outbreaks of CRE may require extraordinary infection control measures. An approach combining point-prevalence surveillance of colonization, detection of environmental and common-equipment contamination, with the implementation of a bundle consisting of chlorhexidine baths, cohorting of colonized patients and health care personnel, increased environmental cleaning, and staff education may be effective in controlling outbreaks of CRE.48

Nevertheless, control of CRE may prove exceptionally difficult. A recent high-profile outbreak of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center in Maryland caused infections in 18 patients, 11 of whom died.49 Of note, carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected in this outbreak in both respiratory equipment and sink drains. The outbreak was ultimately contained by detection through surveillance cultures and by strict cohorting of colonized patients, which minimized common medical equipment and personnel between affected patients and other patients in the hospital. Additionally, rooms were sanitized with hydrogen peroxide vapor, and sinks and drains where carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae was detected were removed.

CHALLENGES IN THE MICROBIOLOGY LABORATORY

Adequate treatment and control of CRE infections is predicated upon their accurate and prompt diagnosis from patient samples in the clinical microbiology laboratory.50

Traditional and current culture-based methods take several days to provide that information, delaying effective antibiotic therapy and permitting the transmission of undetected CRE. Furthermore, interpretative criteria of minimal inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of carbapenems recently required readjustment, as many KPC-producing strains of K pneumoniae had MICs below the previous breakpoint of resistance. In the past, this contributed to instances of “silent” dissemination of KPC-producing K pneumoniae.51

In contrast, using the new lower breakpoints of resistance for carbapenems without using a phenotypic test such as the modified Hodge test or the carbapenem-EDTA combination tests will result in a lack of differentiation between various mechanisms of carbapenem resistance.28,52,53 This may be clinically relevant, as the clinical response to carbapenem therapy may vary depending on the mechanism of resistance.

GENERAL PRINCIPLES APPLY

In treating patients infected with CRE, clinicians need to strictly observe general principles of infectious disease management to ensure the best possible outcomes. These include:

Timely and accurate diagnosis, as discussed above.

Source control, which should include drainage of any infected collections, and removal of lines, devices, and urinary catheters.

Distinguishing between infection and colonization. CRE are often encountered as urinary isolates, and the distinction between asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection may be extremely difficult, especially in residents of long-term care facilities with chronic indwelling catheters, who are thegroup at highest risk of CRE colonization and infection. Urinalysis may be helpful in the absence of pyuria, as this rules out an infection; however, it must be emphasized that the presence of pyuria is not a helpful feature, as pyuria is common in both asymptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection.54 Symptoms should be carefully evaluated in every patient with bacteriuria, and urinary tract infection should be a diagnosis of exclusion in patients with functional symptoms such as confusion or falls.

Selection of the most appropriate antibiotic regimen. While the emphasis is often on the antibiotic regimen, the above elements should not be neglected.

A DWINDLING THERAPEUTIC ARSENAL

Clinicians treating CRE infections are left with only a few antibiotic options. These options are generally limited by a lack of clinical data on efficacy, as well as by concerns about toxicity. These “drugs of last resort” include polymyxins (such as colistin), aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and fosfomycin. The role of carbapenem therapy, potentially in combination regimens, in a high-dose prolonged infusion, or even “double carbapenem therapy” remains to be determined.37,55,56

Colistin

Colistin is one of the first-line agents for treating CRE infections. First introduced in the 1950s, its use was mostly abandoned in favor of aminoglycosides. A proportion of the data on safety and efficacy of colistin, therefore, is based on older, less rigorous studies.

Neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity are the two main concerns with colistin, and while the incidence of these adverse events does appear to be lower with modern preparations, it is still substantial.57 Dosing issues have not been completely clarified either, especially in relation to renal clearance and in patients on renal replacement therapy.58,59 Unfortunately, there have been reports of outbreaks of CRE displaying resistance to colistin.60

Tigecycline

Tigecycline is a newer antibiotic of the glycylcycline class. Like colistin, it has no oral preparation for systemic infections.

The main side effect of tigecycline is nausea.61 Other reported issues include pancreatitis and extreme alkaline phosphatase elevations.

The efficacy of tigecycline has come into question in view of meta-analyses of clinical trials, some of which have shown higher mortality rates in patients treated with tigecycline than with comparator agents.62–65 Based on these data, the US Food and Drug Administration issued a warning in 2010 regarding the increased mortality risk. Although these meta-analyses did not include patients with CRE for whom available comparators would have been ineffective, it is an important safety signal.

The efficacy of tigecycline is further limited by increasing in vitro resistance in CRE. Serum and urinary levels of tigecycline are low, and most experts discourage the use of tigecycline as monotherapy for blood stream or urinary tract infections.

Aminoglycosides

CRE display variable in vitro susceptibility to different aminoglycosides. If the organism is susceptible, aminoglycosides may be very useful in the treatment of CRE infections, especially urinary tract infectons. In a study of carbapenem-resistant K pneumoniae urinary tract infections, patients who were treated with polymyxins or tigecycline were significantly less likely to have clearance of their urine as compared with patients treated with aminoglycosides.66

Ototoxicity and nephrotoxicity are demonstrated adverse effects of aminoglycosides. Close monitoring of serum levels, interval audiology examinations at baseline and during therapy, and the use of extended-interval dosing may help to decrease the incidence of these toxicities.

Fosfomycin

Fosfomycin is only available as an oral formulation in the United States, although intravenous administration has been used in other countries. It is exclusively used to treat urinary tract infections.

CRE often retain susceptibility to fosfomycin, and clearance of urine in cystitis may be attempted with this agent to avoid the need for intravenous treatment.29,67

Combination therapy, other topics to be explored

Recent observational reports from Greece, Italy, and the United States describe higher survival rates in patients with CRE infections treated with a combination regimen rather than monotherapy with colistin or tigecycline. This is despite reliable activity of colistin and tigecycline, and often in regimens containing carbapenems. Clinical experiments are needed to clarify the value of combination regimens that include carbapenems for the treatment of CRE infections.

Similarly, the role of carbapenems given as a high-dose prolonged infusion or as double carbapenem therapy needs to be explored further.37,55,56,68

Also to be determined is the optimal duration of treatment. To date, there is no evidence that increasing the duration of treatment beyond that recommended for infections with more susceptible bacteria results in improved outcomes. Therefore, commonly used durations include 1 week for complicated urinary tract infections, 2 weeks for bacteremia (from the first day with negative blood cultures and source control), and 8 to 14 days for pneumonia.

A SERIOUS THREAT

The emergence of CRE is a serious threat to the safety of patients in our health care system. CRE are highly successful nosocomial pathogens selected by the use of antibiotics, which burden patients debilitated by advanced age, comorbidities, and medical interventions. Infections with CRE result in poor outcomes, and available treatments of last resort such as tigecycline and colistin are of unclear efficacy and safety.