User login

Hysterectomy for benign disease is a very effective operation to treat moderate to severe uterine bleeding or pain caused by uterine problems. There are 3 main surgical approaches to performing a hysterectomy: vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal.

“Abdominal hysterectomy” is a term that indicates the procedure was performed using a relatively large incision in the abdominal wall. It also is possible for 2 surgical routes to be combined into one operation, such as a laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or a laparoscopic hysterectomy with a mini-laparotomy incision to remove the uterus.

Substantial evidence indicates that vaginal and laparoscopic approaches to hysterectomy result in superior outcomes when compared with abdominal hysterectomy. In this editorial I highlight that data, as well as offer concrete ways in which we can increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy while reducing the current reliance on an abdominal approach.

Vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy are associated with more rapid recoveryAuthors of a meta-analysis of 47 randomized trials involving 5,102 women concluded that women who underwent vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy had faster return to full activity, compared with women who had an abdominal hysterectomy. Compared with vaginal hysterectomy, the abdominal approach required an additional 12 days of postoperative recovery before return to normal activities and 1 additional day of postoperative hospitalization.1

In the same meta-analysis, when compared with the laparoscopic approach, abdominal hysterectomy required 15 additional days to return to normal activity and 2.6 more days of postoperative hospitalization.1 The evidence indicates that to maximize rapid return of the patient to full activity, we should reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease.

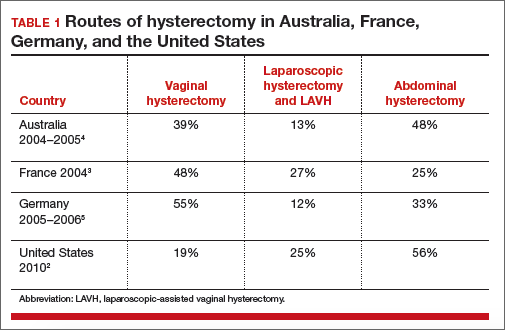

Abdominal hysterectomy is the most frequent US surgical approach In the United States in 2010, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 56% abdominal, 25% laparoscopic, and 19% vaginal.2 In contrast to US practice, French, German, and Australian gynecologists prioritize the vaginal route. In France in 2004, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 48% vaginal, 27% laparoscopic, and 25% abdominal.3 In Australia and Germany, vaginal hysterectomy is performed in 39% and 55% of all hysterectomy cases, respectively—a greater rate of vaginal hysterectomy than observed in the United States (TABLE 1).4,5

Our goal should be 40% or less for abdominal hysterectomy. Based on the experience of French,3 Australian,4 and German5 surgeons, a realistic goal is to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy in the United States to a rate of 40% or less and to increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy to a combined rate of 60% or more.

Perceived contraindications for vaginal hysterectomy may not be valid

Surgeons may avoid selecting a vaginal route for hysterectomy for benign uterine disease when the patient has a markedly enlarged uterus (for example, >16 weeks’ size) or a markedly enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment. The large uterus may be difficult to remove through the vagina and an enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment may make it difficult to enter the peritoneal cavity.

However, large uteri can be removed through the vagina using uterine reduction techniques, including uterine bisection and intramyometrial coring. In one randomized clinical trial,1 women with enlarged uteri were randomly assigned to vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy. Both approaches were successful in removing large uteri. When compared with abdominal hysterectomy, the vaginal approach was associated with shorter operative time, less postoperative fever, less postoperative pain, and fewer hospital days following surgery.

Reference

How will we increase vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease?In order to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy, a multipronged effort is needed:

- Leaders in gynecology need to champion the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Educators in gynecology need to refocus and intensify surgical training to ensure that trainees are confident in their ability to perform both vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Hospital departments need to provide the continuing education and senior surgical mentoring that will facilitate reducing the use of abdominal hysterectomy.

- Quality review committees need to review the indication for abdominal hysterectomy procedures and question whether they could be better performed by a vaginal or laparoscopic route.

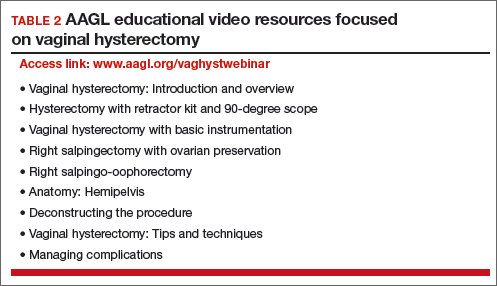

AAGL launches comprehensive video cooperative. A major new educational video offering on vaginal hysterectomy recently was released by the AAGL (TABLE 2). Produced by the AAGL and cosponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, this resource includes detailed videos focused on basic instrumentation and technique, techniques for adnexal surgery at vaginal hysterectomy, and managing complications. I believe this resource will be of great value as momentum builds to increase the use of vaginal hysterectomy. In addition, OBG Management will continue to publish major articles by leading surgeons focused on vaginal hysterectomy.

Are you a champion of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy? Every hospital should identify champions of these approaches. These master surgeons could help advance the capability of the hospital staff to confidently and safely prioritize the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease by mentoring other surgeons. If we reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy we will improve outcomes and significantly advance women’s health.

Select OBG Management publications on vaginal surgery and minimally invasive gynecology

Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most

daunting challenges

Rosanne M. Kho, MD (July 2014)

The Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction ExCITE technique

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (November 2014)

Update on vaginal hysterectomy

Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2015)

The ExCITE technique, Part 2: Simulation made simple

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (Coming soon)

The following articles are based on the master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by AAGL and cosponsored by ACOG and SGS.

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

Barbara S. Levy, MD (October 2015)

Technique for salpingectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (In this issue, page 26)

Managing complications in vaginal hysterectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Coming soon)

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD003677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub5.

- Cohen SL, Vitonis AF, Einarsson JI. Updated hysterectomy surveillance and factors associated with minimally invasive hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(3):e2014.00096.

- David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, Darai E; Collegiale d’Obstétrique et Gynécologie de Paris-Ile de France. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):260–265.

- Hill E, Graham M, Shelley J. Hysterectomy trends in Australia—between 2000/01 and 2004/05. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(2):153–158.

- Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Nationwide rates of conversion from laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):125–133.

Hysterectomy for benign disease is a very effective operation to treat moderate to severe uterine bleeding or pain caused by uterine problems. There are 3 main surgical approaches to performing a hysterectomy: vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal.

“Abdominal hysterectomy” is a term that indicates the procedure was performed using a relatively large incision in the abdominal wall. It also is possible for 2 surgical routes to be combined into one operation, such as a laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or a laparoscopic hysterectomy with a mini-laparotomy incision to remove the uterus.

Substantial evidence indicates that vaginal and laparoscopic approaches to hysterectomy result in superior outcomes when compared with abdominal hysterectomy. In this editorial I highlight that data, as well as offer concrete ways in which we can increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy while reducing the current reliance on an abdominal approach.

Vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy are associated with more rapid recoveryAuthors of a meta-analysis of 47 randomized trials involving 5,102 women concluded that women who underwent vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy had faster return to full activity, compared with women who had an abdominal hysterectomy. Compared with vaginal hysterectomy, the abdominal approach required an additional 12 days of postoperative recovery before return to normal activities and 1 additional day of postoperative hospitalization.1

In the same meta-analysis, when compared with the laparoscopic approach, abdominal hysterectomy required 15 additional days to return to normal activity and 2.6 more days of postoperative hospitalization.1 The evidence indicates that to maximize rapid return of the patient to full activity, we should reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease.

Abdominal hysterectomy is the most frequent US surgical approach In the United States in 2010, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 56% abdominal, 25% laparoscopic, and 19% vaginal.2 In contrast to US practice, French, German, and Australian gynecologists prioritize the vaginal route. In France in 2004, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 48% vaginal, 27% laparoscopic, and 25% abdominal.3 In Australia and Germany, vaginal hysterectomy is performed in 39% and 55% of all hysterectomy cases, respectively—a greater rate of vaginal hysterectomy than observed in the United States (TABLE 1).4,5

Our goal should be 40% or less for abdominal hysterectomy. Based on the experience of French,3 Australian,4 and German5 surgeons, a realistic goal is to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy in the United States to a rate of 40% or less and to increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy to a combined rate of 60% or more.

Perceived contraindications for vaginal hysterectomy may not be valid

Surgeons may avoid selecting a vaginal route for hysterectomy for benign uterine disease when the patient has a markedly enlarged uterus (for example, >16 weeks’ size) or a markedly enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment. The large uterus may be difficult to remove through the vagina and an enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment may make it difficult to enter the peritoneal cavity.

However, large uteri can be removed through the vagina using uterine reduction techniques, including uterine bisection and intramyometrial coring. In one randomized clinical trial,1 women with enlarged uteri were randomly assigned to vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy. Both approaches were successful in removing large uteri. When compared with abdominal hysterectomy, the vaginal approach was associated with shorter operative time, less postoperative fever, less postoperative pain, and fewer hospital days following surgery.

Reference

How will we increase vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease?In order to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy, a multipronged effort is needed:

- Leaders in gynecology need to champion the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Educators in gynecology need to refocus and intensify surgical training to ensure that trainees are confident in their ability to perform both vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Hospital departments need to provide the continuing education and senior surgical mentoring that will facilitate reducing the use of abdominal hysterectomy.

- Quality review committees need to review the indication for abdominal hysterectomy procedures and question whether they could be better performed by a vaginal or laparoscopic route.

AAGL launches comprehensive video cooperative. A major new educational video offering on vaginal hysterectomy recently was released by the AAGL (TABLE 2). Produced by the AAGL and cosponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, this resource includes detailed videos focused on basic instrumentation and technique, techniques for adnexal surgery at vaginal hysterectomy, and managing complications. I believe this resource will be of great value as momentum builds to increase the use of vaginal hysterectomy. In addition, OBG Management will continue to publish major articles by leading surgeons focused on vaginal hysterectomy.

Are you a champion of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy? Every hospital should identify champions of these approaches. These master surgeons could help advance the capability of the hospital staff to confidently and safely prioritize the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease by mentoring other surgeons. If we reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy we will improve outcomes and significantly advance women’s health.

Select OBG Management publications on vaginal surgery and minimally invasive gynecology

Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most

daunting challenges

Rosanne M. Kho, MD (July 2014)

The Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction ExCITE technique

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (November 2014)

Update on vaginal hysterectomy

Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2015)

The ExCITE technique, Part 2: Simulation made simple

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (Coming soon)

The following articles are based on the master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by AAGL and cosponsored by ACOG and SGS.

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

Barbara S. Levy, MD (October 2015)

Technique for salpingectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (In this issue, page 26)

Managing complications in vaginal hysterectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Coming soon)

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Hysterectomy for benign disease is a very effective operation to treat moderate to severe uterine bleeding or pain caused by uterine problems. There are 3 main surgical approaches to performing a hysterectomy: vaginal, laparoscopic, and abdominal.

“Abdominal hysterectomy” is a term that indicates the procedure was performed using a relatively large incision in the abdominal wall. It also is possible for 2 surgical routes to be combined into one operation, such as a laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or a laparoscopic hysterectomy with a mini-laparotomy incision to remove the uterus.

Substantial evidence indicates that vaginal and laparoscopic approaches to hysterectomy result in superior outcomes when compared with abdominal hysterectomy. In this editorial I highlight that data, as well as offer concrete ways in which we can increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy while reducing the current reliance on an abdominal approach.

Vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy are associated with more rapid recoveryAuthors of a meta-analysis of 47 randomized trials involving 5,102 women concluded that women who underwent vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy had faster return to full activity, compared with women who had an abdominal hysterectomy. Compared with vaginal hysterectomy, the abdominal approach required an additional 12 days of postoperative recovery before return to normal activities and 1 additional day of postoperative hospitalization.1

In the same meta-analysis, when compared with the laparoscopic approach, abdominal hysterectomy required 15 additional days to return to normal activity and 2.6 more days of postoperative hospitalization.1 The evidence indicates that to maximize rapid return of the patient to full activity, we should reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy for benign disease.

Abdominal hysterectomy is the most frequent US surgical approach In the United States in 2010, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 56% abdominal, 25% laparoscopic, and 19% vaginal.2 In contrast to US practice, French, German, and Australian gynecologists prioritize the vaginal route. In France in 2004, the rates of hysterectomy by route were 48% vaginal, 27% laparoscopic, and 25% abdominal.3 In Australia and Germany, vaginal hysterectomy is performed in 39% and 55% of all hysterectomy cases, respectively—a greater rate of vaginal hysterectomy than observed in the United States (TABLE 1).4,5

Our goal should be 40% or less for abdominal hysterectomy. Based on the experience of French,3 Australian,4 and German5 surgeons, a realistic goal is to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy in the United States to a rate of 40% or less and to increase the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy to a combined rate of 60% or more.

Perceived contraindications for vaginal hysterectomy may not be valid

Surgeons may avoid selecting a vaginal route for hysterectomy for benign uterine disease when the patient has a markedly enlarged uterus (for example, >16 weeks’ size) or a markedly enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment. The large uterus may be difficult to remove through the vagina and an enlarged cervix or lower uterine segment may make it difficult to enter the peritoneal cavity.

However, large uteri can be removed through the vagina using uterine reduction techniques, including uterine bisection and intramyometrial coring. In one randomized clinical trial,1 women with enlarged uteri were randomly assigned to vaginal or abdominal hysterectomy. Both approaches were successful in removing large uteri. When compared with abdominal hysterectomy, the vaginal approach was associated with shorter operative time, less postoperative fever, less postoperative pain, and fewer hospital days following surgery.

Reference

How will we increase vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease?In order to reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy, a multipronged effort is needed:

- Leaders in gynecology need to champion the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Educators in gynecology need to refocus and intensify surgical training to ensure that trainees are confident in their ability to perform both vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy.

- Hospital departments need to provide the continuing education and senior surgical mentoring that will facilitate reducing the use of abdominal hysterectomy.

- Quality review committees need to review the indication for abdominal hysterectomy procedures and question whether they could be better performed by a vaginal or laparoscopic route.

AAGL launches comprehensive video cooperative. A major new educational video offering on vaginal hysterectomy recently was released by the AAGL (TABLE 2). Produced by the AAGL and cosponsored by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons, this resource includes detailed videos focused on basic instrumentation and technique, techniques for adnexal surgery at vaginal hysterectomy, and managing complications. I believe this resource will be of great value as momentum builds to increase the use of vaginal hysterectomy. In addition, OBG Management will continue to publish major articles by leading surgeons focused on vaginal hysterectomy.

Are you a champion of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy? Every hospital should identify champions of these approaches. These master surgeons could help advance the capability of the hospital staff to confidently and safely prioritize the use of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy for benign disease by mentoring other surgeons. If we reduce the use of abdominal hysterectomy we will improve outcomes and significantly advance women’s health.

Select OBG Management publications on vaginal surgery and minimally invasive gynecology

Transforming vaginal hysterectomy: 7 solutions to the most

daunting challenges

Rosanne M. Kho, MD (July 2014)

The Extracorporeal C-Incision Tissue Extraction ExCITE technique

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (November 2014)

Update on vaginal hysterectomy

Barbara S. Levy, MD (September 2015)

The ExCITE technique, Part 2: Simulation made simple

Mireille D. Truong, MD, and Arnold P. Advincula, MD (Coming soon)

The following articles are based on the master class in vaginal hysterectomy produced by AAGL and cosponsored by ACOG and SGS.

Vaginal hysterectomy with basic instrumentation

Barbara S. Levy, MD (October 2015)

Technique for salpingectomy and salpingo-oophorectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (In this issue, page 26)

Managing complications in vaginal hysterectomy

John B. Gebhart, MD, MS (Coming soon)

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD003677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub5.

- Cohen SL, Vitonis AF, Einarsson JI. Updated hysterectomy surveillance and factors associated with minimally invasive hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(3):e2014.00096.

- David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, Darai E; Collegiale d’Obstétrique et Gynécologie de Paris-Ile de France. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):260–265.

- Hill E, Graham M, Shelley J. Hysterectomy trends in Australia—between 2000/01 and 2004/05. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(2):153–158.

- Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Nationwide rates of conversion from laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):125–133.

- Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(8):CD003677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub5.

- Cohen SL, Vitonis AF, Einarsson JI. Updated hysterectomy surveillance and factors associated with minimally invasive hysterectomy. JSLS. 2014;18(3):e2014.00096.

- David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, Darai E; Collegiale d’Obstétrique et Gynécologie de Paris-Ile de France. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):260–265.

- Hill E, Graham M, Shelley J. Hysterectomy trends in Australia—between 2000/01 and 2004/05. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2010;50(2):153–158.

- Stang A, Merrill RM, Kuss O. Nationwide rates of conversion from laparoscopic or vaginal hysterectomy to open abdominal hysterectomy in Germany. Eur J Epidemiol. 2011;26(2):125–133.