User login

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

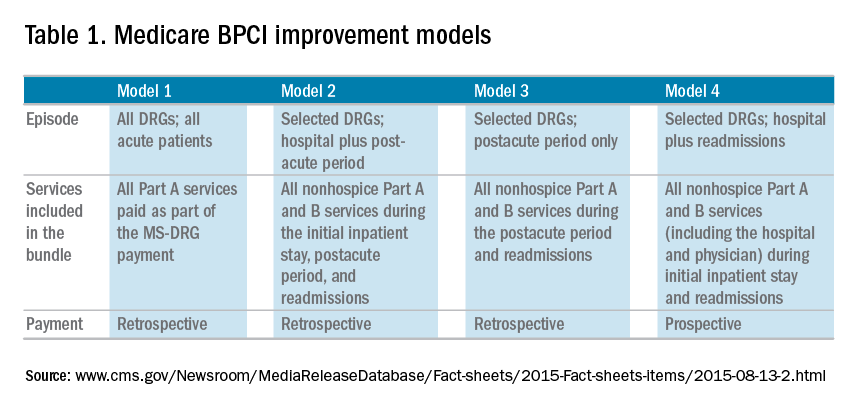

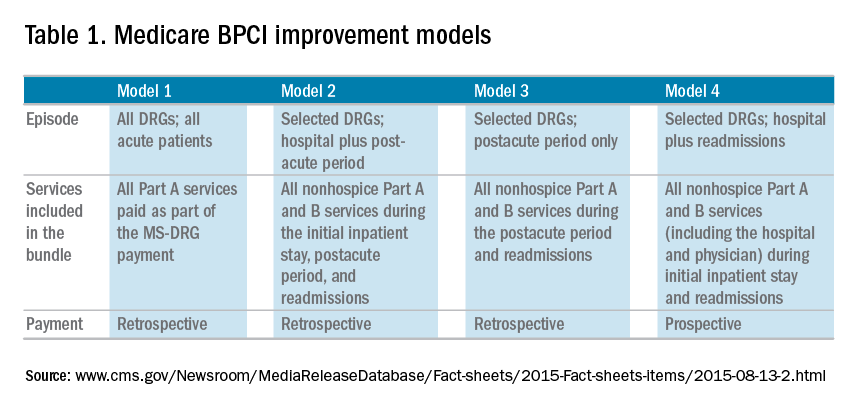

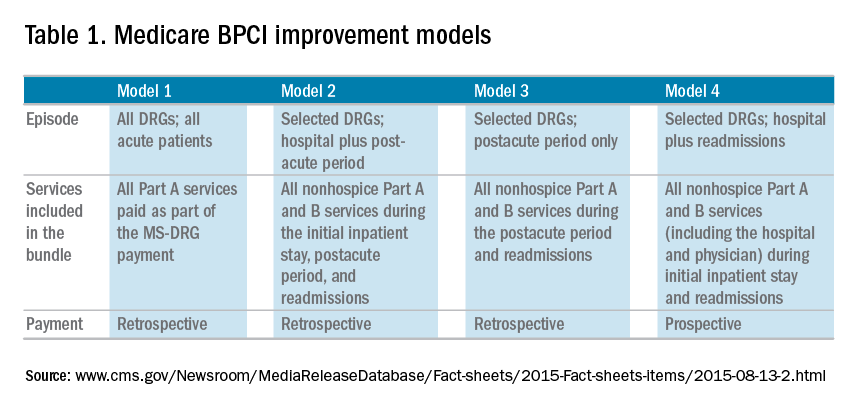

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.

The Medicare Access and Chips Reauthorization Act (MACRA) is now law; it passed with bipartisan, virtually unanimous support in both chambers of Congress. MACRA replaced the Sustainable Growth Rate formula for physician reimbursement and replaced it with a pathway to value-based payment. This law will alter our practices more than the Affordable Care Act and to an extent not seen since the passage of the original Medicare Act. Practices that continue to hang on to our traditional colonoscopy-based fee-for-service reimbursement model will increasingly be marginalized (or discounted) by Medicare, commercial payers, and regional health systems. To thrive in the coming decade, innovative practices will move toward alternative payment models. Many practices have risk-linked bundled payments for colonoscopy, but this step is only for the interim. Long-term success will come to practices that understand the implications of episode payments, specialty medical homes, and total cost of care. Do not wait for the finances to magically appear – start now to build infrastructure. In this month’s article, Dr. Mehta provides a detailed description of how a practice might construct a bundled payment for a common inpatient disorder. No one is paying for this yet, but it will come. Now is not the time to be a “WIMP” (Gastroenterology. 2016;150:295-9).

John I. Allen, MD, MBA, AGAF

Editor in Chief

In January 2016, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) model. This payment model aims to improve the value of care provided to Medicare beneficiaries for hip and knee replacement surgery during the inpatient stay and 90-day period after discharge by holding hospitals accountable for cost and quality.1 It includes hospitals in 67 geographic areas across the United States and marks the first time that a postacute bundled payment model is mandatory for traditional Medicare patients. Although this may not seem to be relevant for gastroenterology, it marks an important signal by CMS that there will likely be more episode-payment models in the future.

Gastroenterologists have not been primary drivers or participants in these models, but gastrointestinal hemorrhage is included as 1 of the 48 clinical conditions for the postacute bundled payment program. In addition, CMS recently announced that clinical episode-based payment for GI hemorrhage will be included in hospital inpatient quality reporting (IQR) for fiscal year 2019.4 This is an opportunity for the field of gastroenterology to take a leadership role in an alternate payment model as it has for colonoscopy bundled payment,5 but it requires an understanding of the history of postacute bundled payments and the opportunities for and challenges to applying this model to GI hemorrhage. In this article, I will describe insights from our health system’s experience in evaluating different postacute bundled payment programs and participating in a GI bundled payment program.

Inpatient and postacute bundled payments

A bundled payment refers to a situation in which hospitals and physicians are incentivized to coordinate care for an episode of care across the continuum and eliminate unnecessary spending. In 1983, Medicare initiated a type of bundled payment for Part A spending on inpatient hospital care by creating prospective payment that is based on diagnosis-related groups (DRGs). This was a response to the rising cost of inpatient care resulting from retrospective payment that is based on hospital charges. Because hospitals would get paid the same amount for similar conditions, it resulted in shortened length of stay and reduction in the rise of inpatient costs, along with no measurable impact on quality of care.6 This was followed by prospective payment for outpatient hospital fees and skilled nursing facility (SNF) care as a result of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. Medicare built on this by bundling physician and hospital fees through demonstration projects in coronary artery bypass graft surgery from 1991 to 1996 and orthopedic and cardiovascular surgery from 2009 to 2012, both resulting in reduced costs and no measurable impact on quality.

The Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) program built on these results in 2013 by expanding to include Part A and B services rendered up to 90 days after discharge, and as of January 2016, it includes 1,574 participants across the country. On a voluntary basis, hospitals, physician groups, and postacute providers and conveners were able to participate in 1 of 4 bundled payment models that were anchored on an inpatient for any of 48 clinical conditions that were based on MS-DRG (Table 1).

• Model 1 defined the episode as the inpatient hospital stay and bundled the facility and physician fees, similar to prior demonstration projects.

• Model 2 is a retrospective bundled payment for Part A and B services in the inpatient hospital stay and up to 90 days after discharge.

• Model 3 is a retrospective model that starts after hospital discharge and includes up to 90 days. (Models 1-3 maintain the current payment structure and retrospectively compare the actual reimbursement with target values that are based on historical data for that hospital with a 2%-3% payment reduction.)

• Model 4 makes a single, prospectively determined global payment to a hospital that encompasses all services during the hospital stay.

Opportunities in inpatient and postacute bundled payments

Participation in bundled payments requires a new set of analytic and organizational capabilities.

• The first step is to identify the patient population on the basis of inclusion and exclusion criteria and to measure the current cost of care through external claims data and internal hospital data. This includes payments for hospital inpatient services, physician fees, postacute care, readmissions, other Part B services, and home health services. The biggest opportunity for postacute bundles is shifting site of service from postacute care to lower-cost settings and reducing readmission rates.

• Subsequently, they need to identify areas of opportunity to reduce expenditure, while also demonstrating consistent or improved quality and outcomes.

• On the basis of this, the team can identify variation in care within the cohort and in comparison with benchmarks across the country.

• After identifying areas of opportunity, the team needs to develop strategies to improve value such as care pathways, information technology tools, care coordination, and remote services.

Of the 48 clinical conditions in BPCI, 4 could be described as related to GI: esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders (Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Group [MS-DRG] 391, 392); gastrointestinal hemorrhage (MS-DRG 377, 378, 379); gastrointestinal obstruction (MS-DRG 388, 389, 390); and major bowel procedure (MS-DRG 329, 330, 331). After evaluating the GI bundles, it was apparent that these were created for billing purposes and were not clinically intuitive, which is why our institution immediately excluded the broad category of esophagitis, gastroenteritis, and other digestive disorders. GI obstruction and major bowel surgery relate to the care of gastroenterologists, but surgeons are typically primary drivers of care for these patients. Thus, we believed that GI hemorrhage was most appropriate because gastroenterologists drive care for this condition, and there is substantial evidence about established guidelines and pathways during this episode.

Bundled payment for gastrointestinal hemorrhage

We built a multidisciplinary team of physicians, data analysts, clinical documentation specialists, and care managers to start developing a plan for improving the value of care in this population. This included data about readmissions and site of postacute care for this population, which were supplemented by chart review of financial outliers and readmissions. We quickly learned about some of the challenges to medical bundles and the GI hemorrhage bundle in particular. It is difficult to identify these patients early in the hospital stay because inclusion is based on a billing code. Many of these patients also have cardiovascular disease, cancer, or cirrhosis, which makes it hard to identify which patients will end up with primary GI hemorrhage coding until after the patient is discharged. They are also on many different inpatient services; in our hospital, there were at least 12 different admitting services. In addition, almost one-third of the patients actually had an admission before this hospitalization, often for different clinical conditions.

Most importantly, it was very challenging to develop protocols to improve the value of care in this population. Most of the patients had many comorbid conditions, so a GI hemorrhage pathway alone would not be sufficient to alter care. The two main areas of opportunity for cost savings in postacute bundled payments are postacute site of service and readmissions, both of which are hard to change for medical GI patients. For medical patients, they have many comorbidities before admission, so postacute site of service is typically driven by which site they were admitted from. This is different from surgical patients who are in SNF or rehabilitation facilities for limited time frames, and there may be more discretion to shift to lower cost settings. In addition, readmissions have not been studied much in GI hemorrhage, so it is not clear how to improve them. On the basis of these factors and the limited sample size for this condition, our health system opted to stop taking financial risk for this population.

Future opportunities for gastroenterology

However, the latest CMS Inpatient Prospective Payment System rule describes the implementation of a new quality metric for hospital IQR called the Gastrointestinal Hemorrhage Clinical Episode-Based Payment. This would hold hospitals accountable for the cost of care for GI hemorrhage admissions plus the 90 days after discharge, similar to model 2 of BPCI. This announcement, as well as the launch of mandatory orthopedic bundles, demonstrates that hospital reimbursement is shifting toward an expansion of bundled payments to include the postacute time frame. This is manifested in postacute bundles, episode-based payment, and readmission penalties. This reignited our GI hemorrhage episode team’s efforts, but with a broader purpose.

Gastroenterologists can take a leadership role in responding to episode-based payments as a way for us to demonstrate value in our collaboration with hospitals, health systems, and payers. The focus on cardiovascular disease as part of readmission penalties and core measures has allowed our cardiology colleagues to partner closely with service lines, learn about episode-based care, and garner resources to build and lead disease and episode teams. Because patients do not fit into the different clinical areas in mutually exclusive categories, we will need to collaborate with other specialties to care for the overlap with other conditions. Many heart failure and myocardial infarction patients will get readmitted for GI hemorrhage, and many GI hemorrhage patients will have concomitant cardiovascular disease or cancer. This suggests that future strategies need to integrate efforts of service lines and that there is greater opportunity for gastroenterologists than just the GI bundles.

Gastroenterologists should also participate in a proactive way. Any new payment mechanism will have some flaws in implementation, so it is more important to do what is right from a clinical standpoint rather than focusing too much on the specific billing code or payment model. These models are evolving, and we have an opportunity to have impact on future implementation. This starts with identifying and including patients from a clinical perspective rather than focusing on specific insurance types that participate in bundled payments. Some examples to improve the value of care in GI hemorrhage include creating evidence-based care pathways that span the episode of care, structured documentation after endoscopy for risk stratification, integrating pathways into the workflow of providers through the electronic health record, and increased coordination between specialties across the continuum of care. Other diagnoses that might be included in future bundles include cirrhosis, bowel obstruction, and inflammatory bowel disease. We can also learn from successful efforts in other clinical specialties that have identified variations in care and implemented a multi-modal strategy to improving care and measuring impact.

References

1. Mechanic, R.E. Mandatory Medicare bundled payment: Is it ready for prime time? N Engl J Med. 2015;373[14]:1291-3.

2. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. January 26, 2015. Available from: http://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2015/01/26/better-smarter-healthier-in-historic-announcement-hhs-sets-clear-goals-and-timeline-for-shifting-medicare-reimbursements-from-volume-to-value.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

3. Patel, K., Presser, E., George, M., et al. Shifting away from fee-for-service: Alternative approaches to payment in gastroenterology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14[4]:497-506.

4. Medicare FY 2016 IPPS final rule. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/FY2016-IPPS-Final-Rule-Home-Page.html. Accessed June 28, 2016.

5. Ketover, S.R. Bundled payment for colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11[5]:454-7.

6. Coulam, R.F., Gaumer, G.L. Medicare’s prospective payment system: a critical appraisal. Health Care Financ Rev Annu Suppl. 1991:45-77.

Dr. Mehta is in the division of gastroenterology, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, and Penn Medicine Center for Health Care Innovation, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. The author discloses no conflicts of interest.