User login

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

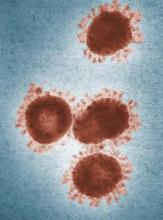

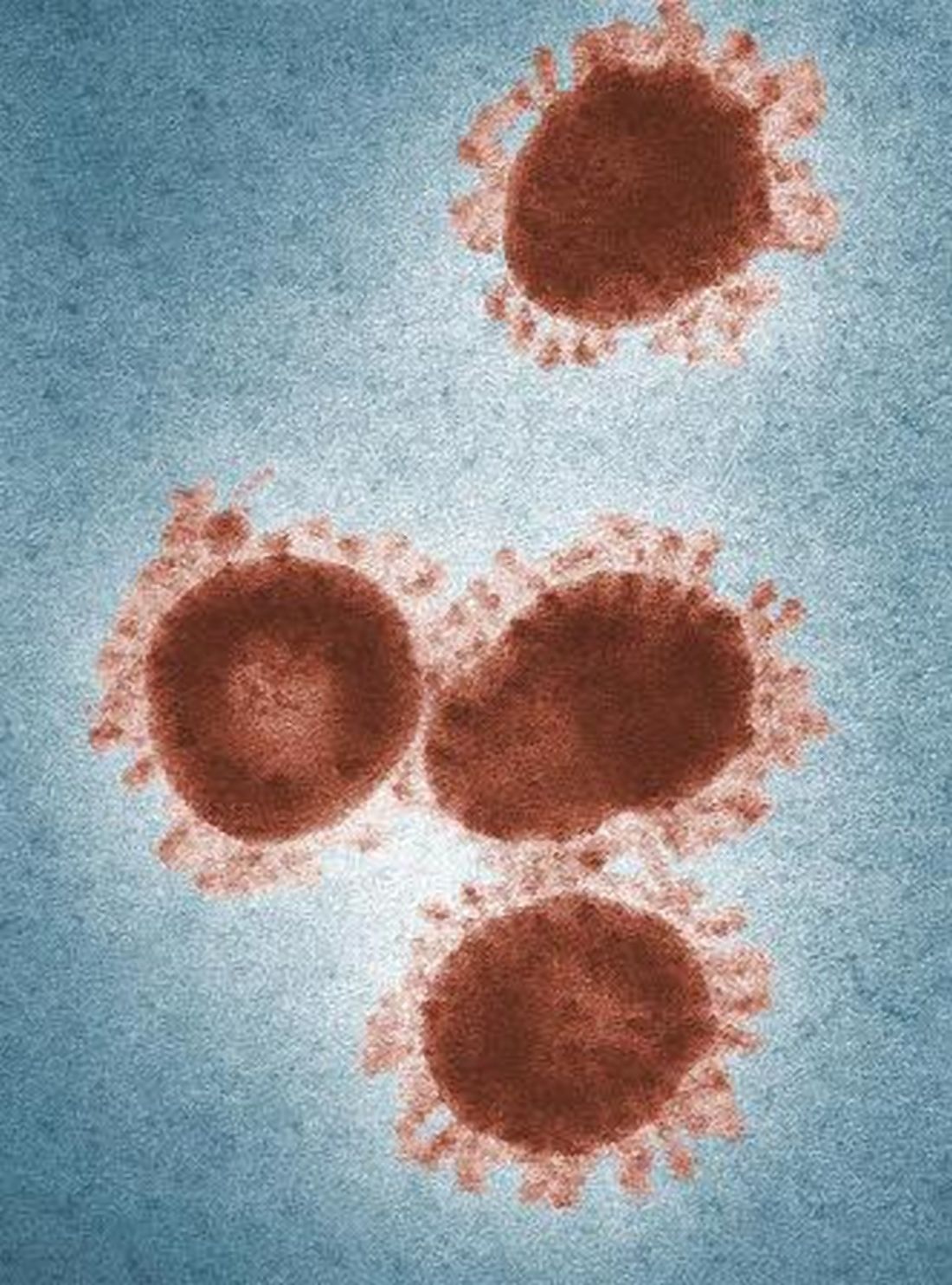

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.

In late January, signs were posted in all of the offices in our faculty medical practice building.

Combined with current worldwide health concerns and flu season, we are now asking all patients two questions:

1. Do you have a fever, cough or shortness of breath?

2. Have you traveled to China in the last 2 weeks, or have you had contact with someone who has and who now is sick?

Similar signs appeared in medical offices and EDs across the city. Truth be told, when the signs first went up, some thought it was an overreaction. I practice in a city in the Southeast that is not a port of entry and has no scheduled international passenger flights. Wuhan City, China and the threat of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) seemed very far away.

As the international tally of cases has grown, so have local concerns.

Hopefully, proactive public health measures to care for the few individuals currently infected in the United States and appropriately assessing individuals arriving from mainland China will prevent widespread circulation of 2019-nCoV here. If this is the case, most of us likely will never see a case of the virus. Still, there are important lessons to be learned from current preparedness efforts.

A travel history is important. Several years ago, during the height of concern over the spread of Ebola, the health care systems in which I practice asked everyone about travel to West Africa as soon as they approached the registration desk. In the intervening years, asking about a travel history largely was delegated to providers, and I suspect it largely was driven by patient presentation. Child presenting with 10 days of fever? The clinician likely took a travel history. Child presenting for runny nose, ear ache, or rash? Maybe not. With more consistent screening, we are learning how frequently our patients and their families do travel, and that is helping us expand our differential diagnosis.

We need to practice cough etiquette. Patients who endorse respiratory symptoms as part of 2019 n-CoV screening are handed a mask. Those who have traveled to China in the last 14 days are promptly escorted to an exam room. In truth, we should be following cough etiquette and offering all patients with respiratory symptoms a mask. Heightened awareness of this practice may help prevent the spread of much more common viruses such as influenza. Reliable processes to recognize and rapidly triage patients with an infectious illness are critically important in ambulatory settings, and now we have an opportunity to trial and improve these processes. No one wants a child with measles or chicken pox to sit in the waiting room!

Offices must stock personal protective equipment to comply with standard precautions. The recommended PPE when caring for a patient with 2019 n-CoV includes a gown, gloves, mask (n95 or PAPR if available), and eye protection, such as a face shield or goggles. An initial survey of PPE supplies locally revealed of shortage of PPE for eye protection in some offices. Eye protection should be readily available in pediatric and other primary care offices because it must be used as part of standard precautions during procedures likely to generate droplets of blood or body fluids. Examples of common procedures that require eye protection include swabbing the nasopharynx to obtain a specimen for respiratory virus testing or swabbing the throat to test for group A streptococcus.

We should use diagnostic testing judiciously. Over the last couple of weeks, we’ve had a couple of patients who wanted to be tested for 2019 n-CoV but did not meet person under investigation (PUI) criteria. Public health authorities, who must approve all 2019 n-CoV testing, said no. This is enforced diagnostic stewardship, but it is a reminder that, when a diagnostic test is performed in a person with a low likelihood of disease, there is a risk of a false-positive result. What if we applied this principle to tests we send routinely? We would send fewer urine cultures in patients with normal urinalyses and stop testing infants for Clostridioides difficile.

Frontline providers must partner with public health colleagues during outbreaks. Providers have been instructed to immediately notify local or state health departments when a patient is suspected of having 2019 n-CoV specifically because the PUI criteria are met. This notification was crucial in diagnosing the first cases of 2019 n-CoV in the United States. Nine of the first 11 U.S. cases were in travelers from Wuhan, and according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, eight of these “were identified as a result of patients seeking clinical care for symptoms and clinicians connecting with the appropriate public health systems.” Locally, daytime and after hours phone numbers for the health department have been posted in offices across our health care system. The state health department is hosting well-attended webinars to provide updates and answer questions from clinicians. We may never have a case of 2019 n-CoV in Kentucky, but activities like these build relationships between providers and our colleagues in public health, strengthening infrastructure and the capacity to respond to future outbreaks. I suspect the same is true in many other communities.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Norton Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at pdnews@mdedge.com.