User login

For the past 40 to 50 years, the first-line treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) has been excisional procedures (including loop electrosurgical excision [LEEP], cone biopsy, cryosurgery, and laser therapy), and these treatments work well. It appears, however, that these procedures potentially can lead to preterm birth.1–3 With results from large, comprehensive meta-analyses that control for such risk factors as smoking and other factors that could contribute to both preterm birth and high-grade CIN, we have learned that excision treatment can result in a 2% to 5% increased risk for preterm birth, depending on the size and the extent of excision performed.1–3 The preterm birth rate in the United States is about 11.4%.4 With about 500,000 excisional treatments for high-grade CIN performed in the United States every year, and about 2% of preterm births caused by excisional procedures, conservatively, about 5,000 to 10,000 US preterm births are directly related to excisional procedures for high-grade CIN annually.

Clearly, excisional treatment for high-grade CIN and its connection to preterm birth adds to health care costs and long-term morbidity because babies that are born preterm potentially have diminished functionality. We need a better treatment approach other than excision to CIN, which is known to be a virally mediated disease. Consider the fact that just because excisional procedures remove potentially cancerous cells does not mean that these treatments remove the underlying reason behind the high-grade CIN—HPV. We cannot cut out a virus. Consequently, many studies have explored better-targeted therapies against high-grade CIN. Immune-based therapies, which can train a patient’s own immune system to attack HPV-infected cells, are exciting possibilities.

In this Update, I focus on 2 studies of immune-based therapies to treat cervical cancer. In addition, I discuss long-term follow-up data that are available regarding efficacy of primary HPV testing.

HPV therapeutic vaccine shows promise in RCT

Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2078-2088.

While the promise of immune-based therapies to target a virally mediated disease has good scientific rationale, there have been many generally negative studies published in the past 15 years on immune-based targeted therapies. This study by Trimble and colleagues has interesting results because it is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using a DNA vaccine delivered with a novel approach called electroporation. Electroporation generates a small electrical shot at the vaccine site that potentially increases a vaccine's DNA uptake and the patient's immune response.

Details of the study

Women aged 18 to 55 years with HPV16- or HPV18-positive high-grade CIN from 36 academic and private gynecology practices in 7 countries were assigned in a 3:1 blinded randomization to receive vaccine (6 mg; VGX-3100) or placebo (1 mL), given intramuscularly at 0, 4, and 12 weeks. Patients were stratified by age 25 or older versus younger than 25 and by CIN2 versus CIN3. The primary efficacy endpoint was regression to CIN1 or normal pathology 36 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

A mandatory interim safety colposcopy was performed 12 weeks after the third vaccine dose. At 36 weeks (the primary endpoint visit), patients with colposcopic evidence of residual disease underwent standard excision (LEEP or cone). In patients with no evidence of disease, investigators could biopsy the site of the original lesions. At 40 weeks, when all patients had completed their first visit after the primary endpoint, the data were unmasked. Long-term follow-up data were collected on all patients with remaining visits. Patients and study site investigators and personnel stayed masked to treatment until study data were final.

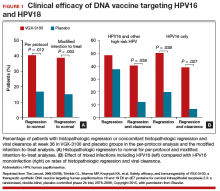

Results indicated a significant clinical response as well as an immune response in those patients who were treated with electroporation and the vaccine versus electroporation and placebo. In the per-protocol analysis, 53 (49.5%) of 107 vaccine recipients and 11 (30.6%) of 36 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (percentage point difference [PPD], 19.0 [95% confidence interval CI, 1.4-36.6]; P = .034) (FIGURE 1). In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, 55 (48.2%) of 114 vaccine recipients and 12 (30.0%) of 40 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (PPD, 18.2; 95% CI, 1.3-34.4; P = .034).

Injection-site reactions occurred in most patients, but only erythema was significantly more common in the vaccine group than in the placebo group (PPD, 21.3 [95% CI, 5.3-37.8]; P = .007).

What this evidence means for practice

In prior studies of immunotherapies, there have not been good correlations between immune responses and clinical responses, and this is one of the important differences between this study by Trimble and colleagues and prior studies in this space. Unfortunately, immune-based therapies are a "shot in the dark," with researchers not knowing which patients may have an increased immune response but no clinical response or a clinical response but no immune response. The measured immune responses are from peripheral blood, an immune response that might not reflect the milieu of immune responses in the cervical-vaginal tract.

If perfected, technologies like these hold the promise of minimizing the amount of patients who need to undergo excisional procedures because patients' own immune systems have been trained to target HPV-infected cells. The bigger hope is that we will be able to minimize preterm births that are directly related to treatment of dysplasia.

Adoptive T-cell therapy offers targeted treatment for recurrent cervical cancer

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543-1550.

Stevanovic and colleagues have been developing another immune-based therapy that has been tested for other cancers. This uses a method for generating T-cell cultures from HPV-positive cancers and selecting specific HPV oncoprotein- reactive cultures for administration to patients. Termed adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT), this targeted approach to recurrent cervical cancer is what I would consider one of the most intriguing future treatments of cervical disease. In the past, the largest barrier to an effective HPV vaccine to treat cervical cancer has been lack of clinical response to existing cytotoxic regimens. In this, albeit small, trial, investigators found a correlation between HPV reactivity and the infused T cells and objective clinical responses.

What is adoptive T-cell therapy?

ACT allows for more rigorous control over the magnitude of the targeted response than tumor vaccination treatment strategies because the T cells used for therapy are identified and selected in vitro. The cells selected are exposed to cytokines and immunomodulators that influence differentiation during priming and are expanded to large numbers. The resulting number of antigen-specific T cells produced in the peripheral blood is much greater (more than 10-fold) than that possible by current vaccine regimens alone.

Studies conducted by the National Cancer Institute of adoptive transfer of in vitro-selected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were the first to demonstrate the potential of T-cell immunotherapy to eradicate solid tumors.5,6 Among 13 patients with melanoma, treatment with adoptive transfer of ex vivo-amplified autologous tumor-infiltrating T cells resulted in treatment response in 10 of the patients—clinical responses in 6 and mixed responses in 4.

Details of the study

This study by Stevanovic and colleagues involved 9 patients with metastatic cervical cancer who previously had received optimal recommended chemotherapy or concomitant chemoradiotherapy regimens. Patients were treated with a single infusion of tumor-infiltrating T cells specifically selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Patients received lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy before ACT and aldesleukin chemotherapy injection after ACT.

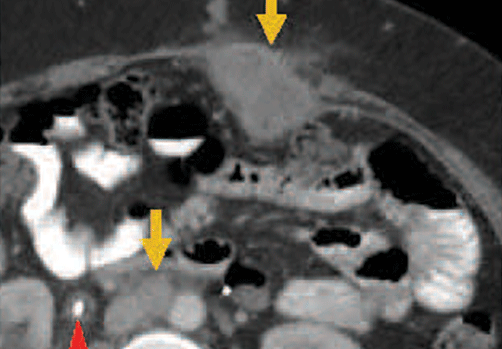

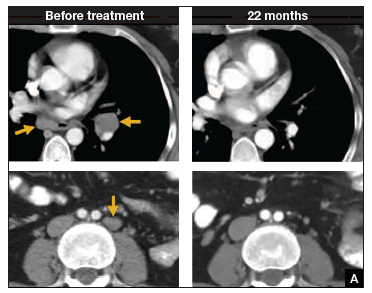

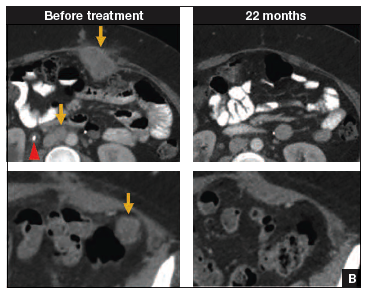

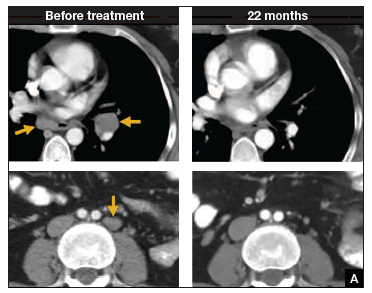

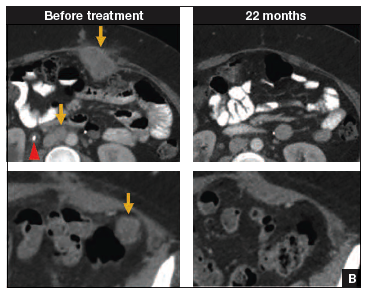

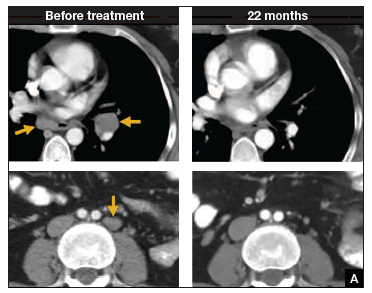

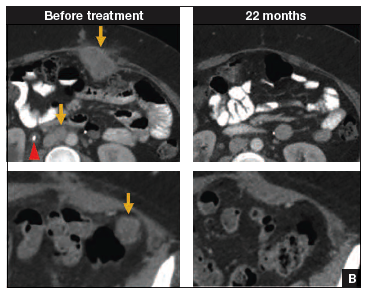

In such a phase I population, one would not expect clinical responses over persistent stable disease. However, in this small trial, 2 patients had complete tumor regression and 1 patient had a partial treatment response, demonstrating that a complete response to metastatic cervical cancer can occur after a single infusion of HPV-TILs. The partial response lasted 3 months. The 2 complete responses were ongoing 22 and 15 months after treatment (FIGURE 2).

Editorialists point out that, only when the infusion product had reactivity against the HPV E6 and E7 peptides did the patients show objective clinical response, suggesting it was the immune response that contributed to the tumor regression.7 In addition, in the 3 patients with objective responses, HPV-specific T cells persisted in peripheral blood for several months.

| FIGURE 2 Patients with complete tumor responses with adoptive T-cell therapy | ||

|  | |

Two patients with metastatic cervical cancer had complete tumor responses with treatment with tumor-infiltrating T cells selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans obtained before treatment and at most recent follow-up for both patients. (A) First patient (patient 3) had disease involving para-aortic, bilateral hilar, subcarinal, and left iliac lymph nodes (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 22 months after treatment. (B) Second patient (patient 6) had metastatic disease in para-aortic lymph node, abdominal wall, aortocaval lymph node, left pericolic pelvic mass, and right ureteral nodule (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 15 months after treatment. (Red arrowhead indicates ureteral stent that was removed after right ureteral tumor regressed.) | ||

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells.J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543–1550. Used with permission.

What this evidence means for practice

The recent approval of bevacizumab has been a major breakthrough in the treatment of advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. Although ACT is a treatment that is in early clinical development, it is the next major advance in this area. Its promise is currently limited, as the process is cumbersome and complex, involving surgical removal of a patient's lymph nodes, culturing of the T cells from the lymph nodes, and infusing the T cells with the oncoproteins that will train those T cells to infiltrate the cancer tumor. The process is wrought with potential problems in laboratory and translational techniques. However, this group of investigators from the NCI has perfected the process of ACT, creating T cells that will target the HPV that is integrated into each cervical cancer tumor.

The patients who demonstrated good T-cell reactivity against HPV were the ones who had a treatment response, which demonstrates the targeted precision of ACT therapy. There might come a day when we can select patients with recurrent cervical cancer who are going to have T-cell reactivity, and send them for treatment to a center specialized in ACT. Typically in phase 1 trials, we are happy to see a number of patients responding with stable disease. In this trial, 2 patients had a complete response. The results demonstrated by Stevanovic and colleagues are very exciting for the future treatment of patients with cervical cancer.

Primary HPV screening shows up to 70% greater protection against invasive cervical cancer than cytology

Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):424-532.

In my 2015 "Update on Cervical Disease,"8 I discussed the newly published interim guidance for managing abnormal screening results for cervical cancer from a collective expert panel from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 4 more societies.9 The guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Papanicolaou test. In 2016, follow-up data from 4 RCTs provide long-term data on the efficacy of HPV primary testing.

Details of the trial

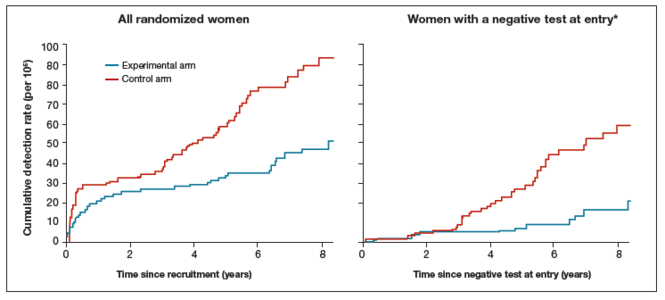

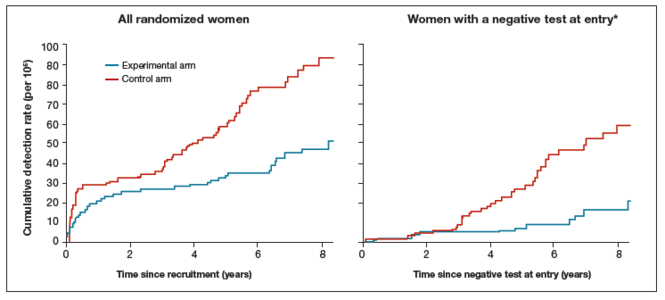

Incidence of invasive cervical cancer was the endpoint in 4 European trials comparing HPV-based with cytology-based screening. In total, 176,464 women aged 20 to 64 years were randomly assigned to either screening strategy. Median follow-up was 6.5 years (1,214,415 person-years). Using screening, pathology, and cancer registries investigators identified 107 invasive cervical carcinomas, with masked review of histologic specimens and reports.

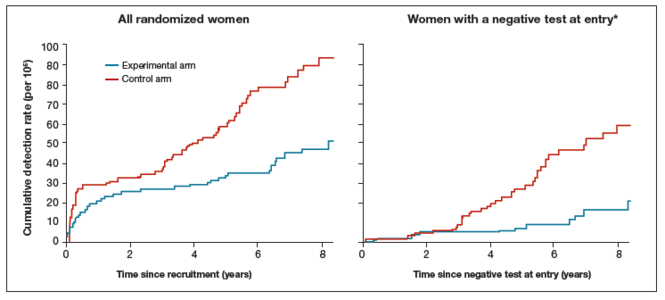

Investigators calculated the rate ratios (defined as the cancer detection rate in the primary HPV testing-based versus cytology-based arms) for incidence of invasive cervical cancer. During the first 2.5 years of follow-up, detection of invasive cancer was similar between screening methods (0.79, 0.46-1.36). Thereafter, however, cumulative cancer detection was lower in the primary HPV testing-based arm (0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative cytology test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 15.4 per 105 (95% CI, 7.9-27.0) and 36.0 per 105 (23.2-53.5), respectively. At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative HPV test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 4.6 per 105 (1.1-12.1) and 8.7 per 105 (3.3-18.6), respectively (FIGURE 3).

| FIGURE 3 Cumulative detection of invasive cervical carcinoma | ||

| ||

*Observations are censored 2.5 years after CIN2 or CIN3 detection, if any.

| ||

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The 4 studies in this report were completed across Europe (in England, Netherlands, Sweden, and Italy): different regions, different sites, hospitals, and screening systems. The women in Europe are not any different than the women in the United States in terms of rates of HPV and age and incidence of HPV. Therefore, these results are globally generalizable.

The US trial by Wright and colleagues10 that led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of HPV primary testing was different than this European study in that all trial sites had to perform screening in the same way. In addition, the end point was high-grade dysplasia; in this trial by Ronco and colleagues the end point is cancer. These current investigators found no difference with either screening arm in terms of detection of invasive cervical cancer. Even more interesting is that, over time, the cervical cancer rates in the primary HPV testing-based arm were much less than that in the cytology-based arm.

The real strengths of this study are the long-term follow-up and the study size. We are not likely to see validation cohorts this big again. This study demonstrates that, overall, we should be able to continue to reduce the incidence of invasive cervical cancer with a primary HPV testing-based screening strategy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Conner SN, Frey HA, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Colditz GA, Tuuli MG. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):752−761.

- Kyrgiou M, Valasoulis G, Stasinou SM, et al. Proportion of cervical excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):141−147.

- Miller ES, Grobman WA. The association between cervical excisional procedures, midtrimester cervical length, and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(3):242.e1−e4.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. Published January 15, 2015. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346−2357.

- Zsiros E, Tsuli T, Odunsi K. Adoptive T-cell therapy is a promising salvage approach for advanced or recurrent metastatic cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1521−1522.

- Einstein MH. Update on cervical disease: New ammo for HPV prevention and screening. OBG Manag. 2015;27(5):32−39.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

For the past 40 to 50 years, the first-line treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) has been excisional procedures (including loop electrosurgical excision [LEEP], cone biopsy, cryosurgery, and laser therapy), and these treatments work well. It appears, however, that these procedures potentially can lead to preterm birth.1–3 With results from large, comprehensive meta-analyses that control for such risk factors as smoking and other factors that could contribute to both preterm birth and high-grade CIN, we have learned that excision treatment can result in a 2% to 5% increased risk for preterm birth, depending on the size and the extent of excision performed.1–3 The preterm birth rate in the United States is about 11.4%.4 With about 500,000 excisional treatments for high-grade CIN performed in the United States every year, and about 2% of preterm births caused by excisional procedures, conservatively, about 5,000 to 10,000 US preterm births are directly related to excisional procedures for high-grade CIN annually.

Clearly, excisional treatment for high-grade CIN and its connection to preterm birth adds to health care costs and long-term morbidity because babies that are born preterm potentially have diminished functionality. We need a better treatment approach other than excision to CIN, which is known to be a virally mediated disease. Consider the fact that just because excisional procedures remove potentially cancerous cells does not mean that these treatments remove the underlying reason behind the high-grade CIN—HPV. We cannot cut out a virus. Consequently, many studies have explored better-targeted therapies against high-grade CIN. Immune-based therapies, which can train a patient’s own immune system to attack HPV-infected cells, are exciting possibilities.

In this Update, I focus on 2 studies of immune-based therapies to treat cervical cancer. In addition, I discuss long-term follow-up data that are available regarding efficacy of primary HPV testing.

HPV therapeutic vaccine shows promise in RCT

Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2078-2088.

While the promise of immune-based therapies to target a virally mediated disease has good scientific rationale, there have been many generally negative studies published in the past 15 years on immune-based targeted therapies. This study by Trimble and colleagues has interesting results because it is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using a DNA vaccine delivered with a novel approach called electroporation. Electroporation generates a small electrical shot at the vaccine site that potentially increases a vaccine's DNA uptake and the patient's immune response.

Details of the study

Women aged 18 to 55 years with HPV16- or HPV18-positive high-grade CIN from 36 academic and private gynecology practices in 7 countries were assigned in a 3:1 blinded randomization to receive vaccine (6 mg; VGX-3100) or placebo (1 mL), given intramuscularly at 0, 4, and 12 weeks. Patients were stratified by age 25 or older versus younger than 25 and by CIN2 versus CIN3. The primary efficacy endpoint was regression to CIN1 or normal pathology 36 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

A mandatory interim safety colposcopy was performed 12 weeks after the third vaccine dose. At 36 weeks (the primary endpoint visit), patients with colposcopic evidence of residual disease underwent standard excision (LEEP or cone). In patients with no evidence of disease, investigators could biopsy the site of the original lesions. At 40 weeks, when all patients had completed their first visit after the primary endpoint, the data were unmasked. Long-term follow-up data were collected on all patients with remaining visits. Patients and study site investigators and personnel stayed masked to treatment until study data were final.

Results indicated a significant clinical response as well as an immune response in those patients who were treated with electroporation and the vaccine versus electroporation and placebo. In the per-protocol analysis, 53 (49.5%) of 107 vaccine recipients and 11 (30.6%) of 36 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (percentage point difference [PPD], 19.0 [95% confidence interval CI, 1.4-36.6]; P = .034) (FIGURE 1). In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, 55 (48.2%) of 114 vaccine recipients and 12 (30.0%) of 40 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (PPD, 18.2; 95% CI, 1.3-34.4; P = .034).

Injection-site reactions occurred in most patients, but only erythema was significantly more common in the vaccine group than in the placebo group (PPD, 21.3 [95% CI, 5.3-37.8]; P = .007).

What this evidence means for practice

In prior studies of immunotherapies, there have not been good correlations between immune responses and clinical responses, and this is one of the important differences between this study by Trimble and colleagues and prior studies in this space. Unfortunately, immune-based therapies are a "shot in the dark," with researchers not knowing which patients may have an increased immune response but no clinical response or a clinical response but no immune response. The measured immune responses are from peripheral blood, an immune response that might not reflect the milieu of immune responses in the cervical-vaginal tract.

If perfected, technologies like these hold the promise of minimizing the amount of patients who need to undergo excisional procedures because patients' own immune systems have been trained to target HPV-infected cells. The bigger hope is that we will be able to minimize preterm births that are directly related to treatment of dysplasia.

Adoptive T-cell therapy offers targeted treatment for recurrent cervical cancer

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543-1550.

Stevanovic and colleagues have been developing another immune-based therapy that has been tested for other cancers. This uses a method for generating T-cell cultures from HPV-positive cancers and selecting specific HPV oncoprotein- reactive cultures for administration to patients. Termed adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT), this targeted approach to recurrent cervical cancer is what I would consider one of the most intriguing future treatments of cervical disease. In the past, the largest barrier to an effective HPV vaccine to treat cervical cancer has been lack of clinical response to existing cytotoxic regimens. In this, albeit small, trial, investigators found a correlation between HPV reactivity and the infused T cells and objective clinical responses.

What is adoptive T-cell therapy?

ACT allows for more rigorous control over the magnitude of the targeted response than tumor vaccination treatment strategies because the T cells used for therapy are identified and selected in vitro. The cells selected are exposed to cytokines and immunomodulators that influence differentiation during priming and are expanded to large numbers. The resulting number of antigen-specific T cells produced in the peripheral blood is much greater (more than 10-fold) than that possible by current vaccine regimens alone.

Studies conducted by the National Cancer Institute of adoptive transfer of in vitro-selected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were the first to demonstrate the potential of T-cell immunotherapy to eradicate solid tumors.5,6 Among 13 patients with melanoma, treatment with adoptive transfer of ex vivo-amplified autologous tumor-infiltrating T cells resulted in treatment response in 10 of the patients—clinical responses in 6 and mixed responses in 4.

Details of the study

This study by Stevanovic and colleagues involved 9 patients with metastatic cervical cancer who previously had received optimal recommended chemotherapy or concomitant chemoradiotherapy regimens. Patients were treated with a single infusion of tumor-infiltrating T cells specifically selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Patients received lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy before ACT and aldesleukin chemotherapy injection after ACT.

In such a phase I population, one would not expect clinical responses over persistent stable disease. However, in this small trial, 2 patients had complete tumor regression and 1 patient had a partial treatment response, demonstrating that a complete response to metastatic cervical cancer can occur after a single infusion of HPV-TILs. The partial response lasted 3 months. The 2 complete responses were ongoing 22 and 15 months after treatment (FIGURE 2).

Editorialists point out that, only when the infusion product had reactivity against the HPV E6 and E7 peptides did the patients show objective clinical response, suggesting it was the immune response that contributed to the tumor regression.7 In addition, in the 3 patients with objective responses, HPV-specific T cells persisted in peripheral blood for several months.

| FIGURE 2 Patients with complete tumor responses with adoptive T-cell therapy | ||

|  | |

Two patients with metastatic cervical cancer had complete tumor responses with treatment with tumor-infiltrating T cells selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans obtained before treatment and at most recent follow-up for both patients. (A) First patient (patient 3) had disease involving para-aortic, bilateral hilar, subcarinal, and left iliac lymph nodes (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 22 months after treatment. (B) Second patient (patient 6) had metastatic disease in para-aortic lymph node, abdominal wall, aortocaval lymph node, left pericolic pelvic mass, and right ureteral nodule (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 15 months after treatment. (Red arrowhead indicates ureteral stent that was removed after right ureteral tumor regressed.) | ||

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells.J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543–1550. Used with permission.

What this evidence means for practice

The recent approval of bevacizumab has been a major breakthrough in the treatment of advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. Although ACT is a treatment that is in early clinical development, it is the next major advance in this area. Its promise is currently limited, as the process is cumbersome and complex, involving surgical removal of a patient's lymph nodes, culturing of the T cells from the lymph nodes, and infusing the T cells with the oncoproteins that will train those T cells to infiltrate the cancer tumor. The process is wrought with potential problems in laboratory and translational techniques. However, this group of investigators from the NCI has perfected the process of ACT, creating T cells that will target the HPV that is integrated into each cervical cancer tumor.

The patients who demonstrated good T-cell reactivity against HPV were the ones who had a treatment response, which demonstrates the targeted precision of ACT therapy. There might come a day when we can select patients with recurrent cervical cancer who are going to have T-cell reactivity, and send them for treatment to a center specialized in ACT. Typically in phase 1 trials, we are happy to see a number of patients responding with stable disease. In this trial, 2 patients had a complete response. The results demonstrated by Stevanovic and colleagues are very exciting for the future treatment of patients with cervical cancer.

Primary HPV screening shows up to 70% greater protection against invasive cervical cancer than cytology

Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):424-532.

In my 2015 "Update on Cervical Disease,"8 I discussed the newly published interim guidance for managing abnormal screening results for cervical cancer from a collective expert panel from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 4 more societies.9 The guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Papanicolaou test. In 2016, follow-up data from 4 RCTs provide long-term data on the efficacy of HPV primary testing.

Details of the trial

Incidence of invasive cervical cancer was the endpoint in 4 European trials comparing HPV-based with cytology-based screening. In total, 176,464 women aged 20 to 64 years were randomly assigned to either screening strategy. Median follow-up was 6.5 years (1,214,415 person-years). Using screening, pathology, and cancer registries investigators identified 107 invasive cervical carcinomas, with masked review of histologic specimens and reports.

Investigators calculated the rate ratios (defined as the cancer detection rate in the primary HPV testing-based versus cytology-based arms) for incidence of invasive cervical cancer. During the first 2.5 years of follow-up, detection of invasive cancer was similar between screening methods (0.79, 0.46-1.36). Thereafter, however, cumulative cancer detection was lower in the primary HPV testing-based arm (0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative cytology test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 15.4 per 105 (95% CI, 7.9-27.0) and 36.0 per 105 (23.2-53.5), respectively. At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative HPV test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 4.6 per 105 (1.1-12.1) and 8.7 per 105 (3.3-18.6), respectively (FIGURE 3).

| FIGURE 3 Cumulative detection of invasive cervical carcinoma | ||

| ||

*Observations are censored 2.5 years after CIN2 or CIN3 detection, if any.

| ||

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The 4 studies in this report were completed across Europe (in England, Netherlands, Sweden, and Italy): different regions, different sites, hospitals, and screening systems. The women in Europe are not any different than the women in the United States in terms of rates of HPV and age and incidence of HPV. Therefore, these results are globally generalizable.

The US trial by Wright and colleagues10 that led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of HPV primary testing was different than this European study in that all trial sites had to perform screening in the same way. In addition, the end point was high-grade dysplasia; in this trial by Ronco and colleagues the end point is cancer. These current investigators found no difference with either screening arm in terms of detection of invasive cervical cancer. Even more interesting is that, over time, the cervical cancer rates in the primary HPV testing-based arm were much less than that in the cytology-based arm.

The real strengths of this study are the long-term follow-up and the study size. We are not likely to see validation cohorts this big again. This study demonstrates that, overall, we should be able to continue to reduce the incidence of invasive cervical cancer with a primary HPV testing-based screening strategy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

For the past 40 to 50 years, the first-line treatment for high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) has been excisional procedures (including loop electrosurgical excision [LEEP], cone biopsy, cryosurgery, and laser therapy), and these treatments work well. It appears, however, that these procedures potentially can lead to preterm birth.1–3 With results from large, comprehensive meta-analyses that control for such risk factors as smoking and other factors that could contribute to both preterm birth and high-grade CIN, we have learned that excision treatment can result in a 2% to 5% increased risk for preterm birth, depending on the size and the extent of excision performed.1–3 The preterm birth rate in the United States is about 11.4%.4 With about 500,000 excisional treatments for high-grade CIN performed in the United States every year, and about 2% of preterm births caused by excisional procedures, conservatively, about 5,000 to 10,000 US preterm births are directly related to excisional procedures for high-grade CIN annually.

Clearly, excisional treatment for high-grade CIN and its connection to preterm birth adds to health care costs and long-term morbidity because babies that are born preterm potentially have diminished functionality. We need a better treatment approach other than excision to CIN, which is known to be a virally mediated disease. Consider the fact that just because excisional procedures remove potentially cancerous cells does not mean that these treatments remove the underlying reason behind the high-grade CIN—HPV. We cannot cut out a virus. Consequently, many studies have explored better-targeted therapies against high-grade CIN. Immune-based therapies, which can train a patient’s own immune system to attack HPV-infected cells, are exciting possibilities.

In this Update, I focus on 2 studies of immune-based therapies to treat cervical cancer. In addition, I discuss long-term follow-up data that are available regarding efficacy of primary HPV testing.

HPV therapeutic vaccine shows promise in RCT

Trimble CL, Morrow MP, Kraynyak KA, et al. Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of VGX-3100, a therapeutic synthetic DNA vaccine targeting human papillomavirus 16 and 18 E6 and E7 proteins for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 2/3: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2b trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2078-2088.

While the promise of immune-based therapies to target a virally mediated disease has good scientific rationale, there have been many generally negative studies published in the past 15 years on immune-based targeted therapies. This study by Trimble and colleagues has interesting results because it is a randomized controlled trial (RCT) using a DNA vaccine delivered with a novel approach called electroporation. Electroporation generates a small electrical shot at the vaccine site that potentially increases a vaccine's DNA uptake and the patient's immune response.

Details of the study

Women aged 18 to 55 years with HPV16- or HPV18-positive high-grade CIN from 36 academic and private gynecology practices in 7 countries were assigned in a 3:1 blinded randomization to receive vaccine (6 mg; VGX-3100) or placebo (1 mL), given intramuscularly at 0, 4, and 12 weeks. Patients were stratified by age 25 or older versus younger than 25 and by CIN2 versus CIN3. The primary efficacy endpoint was regression to CIN1 or normal pathology 36 weeks after the first vaccine dose.

A mandatory interim safety colposcopy was performed 12 weeks after the third vaccine dose. At 36 weeks (the primary endpoint visit), patients with colposcopic evidence of residual disease underwent standard excision (LEEP or cone). In patients with no evidence of disease, investigators could biopsy the site of the original lesions. At 40 weeks, when all patients had completed their first visit after the primary endpoint, the data were unmasked. Long-term follow-up data were collected on all patients with remaining visits. Patients and study site investigators and personnel stayed masked to treatment until study data were final.

Results indicated a significant clinical response as well as an immune response in those patients who were treated with electroporation and the vaccine versus electroporation and placebo. In the per-protocol analysis, 53 (49.5%) of 107 vaccine recipients and 11 (30.6%) of 36 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (percentage point difference [PPD], 19.0 [95% confidence interval CI, 1.4-36.6]; P = .034) (FIGURE 1). In the modified intention-to-treat analysis, 55 (48.2%) of 114 vaccine recipients and 12 (30.0%) of 40 placebo recipients had histopathologic regression (PPD, 18.2; 95% CI, 1.3-34.4; P = .034).

Injection-site reactions occurred in most patients, but only erythema was significantly more common in the vaccine group than in the placebo group (PPD, 21.3 [95% CI, 5.3-37.8]; P = .007).

What this evidence means for practice

In prior studies of immunotherapies, there have not been good correlations between immune responses and clinical responses, and this is one of the important differences between this study by Trimble and colleagues and prior studies in this space. Unfortunately, immune-based therapies are a "shot in the dark," with researchers not knowing which patients may have an increased immune response but no clinical response or a clinical response but no immune response. The measured immune responses are from peripheral blood, an immune response that might not reflect the milieu of immune responses in the cervical-vaginal tract.

If perfected, technologies like these hold the promise of minimizing the amount of patients who need to undergo excisional procedures because patients' own immune systems have been trained to target HPV-infected cells. The bigger hope is that we will be able to minimize preterm births that are directly related to treatment of dysplasia.

Adoptive T-cell therapy offers targeted treatment for recurrent cervical cancer

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543-1550.

Stevanovic and colleagues have been developing another immune-based therapy that has been tested for other cancers. This uses a method for generating T-cell cultures from HPV-positive cancers and selecting specific HPV oncoprotein- reactive cultures for administration to patients. Termed adoptive T-cell therapy (ACT), this targeted approach to recurrent cervical cancer is what I would consider one of the most intriguing future treatments of cervical disease. In the past, the largest barrier to an effective HPV vaccine to treat cervical cancer has been lack of clinical response to existing cytotoxic regimens. In this, albeit small, trial, investigators found a correlation between HPV reactivity and the infused T cells and objective clinical responses.

What is adoptive T-cell therapy?

ACT allows for more rigorous control over the magnitude of the targeted response than tumor vaccination treatment strategies because the T cells used for therapy are identified and selected in vitro. The cells selected are exposed to cytokines and immunomodulators that influence differentiation during priming and are expanded to large numbers. The resulting number of antigen-specific T cells produced in the peripheral blood is much greater (more than 10-fold) than that possible by current vaccine regimens alone.

Studies conducted by the National Cancer Institute of adoptive transfer of in vitro-selected tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes were the first to demonstrate the potential of T-cell immunotherapy to eradicate solid tumors.5,6 Among 13 patients with melanoma, treatment with adoptive transfer of ex vivo-amplified autologous tumor-infiltrating T cells resulted in treatment response in 10 of the patients—clinical responses in 6 and mixed responses in 4.

Details of the study

This study by Stevanovic and colleagues involved 9 patients with metastatic cervical cancer who previously had received optimal recommended chemotherapy or concomitant chemoradiotherapy regimens. Patients were treated with a single infusion of tumor-infiltrating T cells specifically selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Patients received lymphocyte-depleting chemotherapy before ACT and aldesleukin chemotherapy injection after ACT.

In such a phase I population, one would not expect clinical responses over persistent stable disease. However, in this small trial, 2 patients had complete tumor regression and 1 patient had a partial treatment response, demonstrating that a complete response to metastatic cervical cancer can occur after a single infusion of HPV-TILs. The partial response lasted 3 months. The 2 complete responses were ongoing 22 and 15 months after treatment (FIGURE 2).

Editorialists point out that, only when the infusion product had reactivity against the HPV E6 and E7 peptides did the patients show objective clinical response, suggesting it was the immune response that contributed to the tumor regression.7 In addition, in the 3 patients with objective responses, HPV-specific T cells persisted in peripheral blood for several months.

| FIGURE 2 Patients with complete tumor responses with adoptive T-cell therapy | ||

|  | |

Two patients with metastatic cervical cancer had complete tumor responses with treatment with tumor-infiltrating T cells selected for HPV E6 and E7 reactivity (HPV-TILs). Contrast-enhanced computed tomography scans obtained before treatment and at most recent follow-up for both patients. (A) First patient (patient 3) had disease involving para-aortic, bilateral hilar, subcarinal, and left iliac lymph nodes (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 22 months after treatment. (B) Second patient (patient 6) had metastatic disease in para-aortic lymph node, abdominal wall, aortocaval lymph node, left pericolic pelvic mass, and right ureteral nodule (gold arrows). Patient had no evidence of disease 15 months after treatment. (Red arrowhead indicates ureteral stent that was removed after right ureteral tumor regressed.) | ||

Stevanovic S, Draper LM, Langhan MM, et al. Complete regression of metastatic cervical cancer after treatment with human papillomavirus-targeted tumor-infiltrating T cells.J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1543–1550. Used with permission.

What this evidence means for practice

The recent approval of bevacizumab has been a major breakthrough in the treatment of advanced and recurrent cervical cancer. Although ACT is a treatment that is in early clinical development, it is the next major advance in this area. Its promise is currently limited, as the process is cumbersome and complex, involving surgical removal of a patient's lymph nodes, culturing of the T cells from the lymph nodes, and infusing the T cells with the oncoproteins that will train those T cells to infiltrate the cancer tumor. The process is wrought with potential problems in laboratory and translational techniques. However, this group of investigators from the NCI has perfected the process of ACT, creating T cells that will target the HPV that is integrated into each cervical cancer tumor.

The patients who demonstrated good T-cell reactivity against HPV were the ones who had a treatment response, which demonstrates the targeted precision of ACT therapy. There might come a day when we can select patients with recurrent cervical cancer who are going to have T-cell reactivity, and send them for treatment to a center specialized in ACT. Typically in phase 1 trials, we are happy to see a number of patients responding with stable disease. In this trial, 2 patients had a complete response. The results demonstrated by Stevanovic and colleagues are very exciting for the future treatment of patients with cervical cancer.

Primary HPV screening shows up to 70% greater protection against invasive cervical cancer than cytology

Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383(9916):424-532.

In my 2015 "Update on Cervical Disease,"8 I discussed the newly published interim guidance for managing abnormal screening results for cervical cancer from a collective expert panel from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, Society of Gynecologic Oncology, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 4 more societies.9 The guidelines support use of HPV testing alone or with the Papanicolaou test. In 2016, follow-up data from 4 RCTs provide long-term data on the efficacy of HPV primary testing.

Details of the trial

Incidence of invasive cervical cancer was the endpoint in 4 European trials comparing HPV-based with cytology-based screening. In total, 176,464 women aged 20 to 64 years were randomly assigned to either screening strategy. Median follow-up was 6.5 years (1,214,415 person-years). Using screening, pathology, and cancer registries investigators identified 107 invasive cervical carcinomas, with masked review of histologic specimens and reports.

Investigators calculated the rate ratios (defined as the cancer detection rate in the primary HPV testing-based versus cytology-based arms) for incidence of invasive cervical cancer. During the first 2.5 years of follow-up, detection of invasive cancer was similar between screening methods (0.79, 0.46-1.36). Thereafter, however, cumulative cancer detection was lower in the primary HPV testing-based arm (0.45; 95% CI, 0.25-0.81).

At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative cytology test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 15.4 per 105 (95% CI, 7.9-27.0) and 36.0 per 105 (23.2-53.5), respectively. At 3.5 and 5.5 years after a negative HPV test on entry, cumulative cancer incidence was 4.6 per 105 (1.1-12.1) and 8.7 per 105 (3.3-18.6), respectively (FIGURE 3).

| FIGURE 3 Cumulative detection of invasive cervical carcinoma | ||

| ||

*Observations are censored 2.5 years after CIN2 or CIN3 detection, if any.

| ||

What this EVIDENCE means for practice

The 4 studies in this report were completed across Europe (in England, Netherlands, Sweden, and Italy): different regions, different sites, hospitals, and screening systems. The women in Europe are not any different than the women in the United States in terms of rates of HPV and age and incidence of HPV. Therefore, these results are globally generalizable.

The US trial by Wright and colleagues10 that led to US Food and Drug Administration approval of HPV primary testing was different than this European study in that all trial sites had to perform screening in the same way. In addition, the end point was high-grade dysplasia; in this trial by Ronco and colleagues the end point is cancer. These current investigators found no difference with either screening arm in terms of detection of invasive cervical cancer. Even more interesting is that, over time, the cervical cancer rates in the primary HPV testing-based arm were much less than that in the cytology-based arm.

The real strengths of this study are the long-term follow-up and the study size. We are not likely to see validation cohorts this big again. This study demonstrates that, overall, we should be able to continue to reduce the incidence of invasive cervical cancer with a primary HPV testing-based screening strategy.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Conner SN, Frey HA, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Colditz GA, Tuuli MG. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):752−761.

- Kyrgiou M, Valasoulis G, Stasinou SM, et al. Proportion of cervical excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):141−147.

- Miller ES, Grobman WA. The association between cervical excisional procedures, midtrimester cervical length, and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(3):242.e1−e4.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. Published January 15, 2015. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346−2357.

- Zsiros E, Tsuli T, Odunsi K. Adoptive T-cell therapy is a promising salvage approach for advanced or recurrent metastatic cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1521−1522.

- Einstein MH. Update on cervical disease: New ammo for HPV prevention and screening. OBG Manag. 2015;27(5):32−39.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

- Conner SN, Frey HA, Cahill AG, Macones GA, Colditz GA, Tuuli MG. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure and risk of preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(4):752−761.

- Kyrgiou M, Valasoulis G, Stasinou SM, et al. Proportion of cervical excision for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia as a predictor of pregnancy outcomes. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):141−147.

- Miller ES, Grobman WA. The association between cervical excisional procedures, midtrimester cervical length, and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;211(3):242.e1−e4.

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Curtin SC, Mathews TJ. Births: Final data for 2013. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2015;64(1):1–65. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr64/nvsr64_01.pdf. Published January 15, 2015. Accessed April 20, 2016.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298(5594):850–854.

- Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Yang JC, et al. Adoptive cell transfer therapy following non-myeloablative but lymphodepleting chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with refractory metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(10):2346−2357.

- Zsiros E, Tsuli T, Odunsi K. Adoptive T-cell therapy is a promising salvage approach for advanced or recurrent metastatic cervical cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(14):1521−1522.

- Einstein MH. Update on cervical disease: New ammo for HPV prevention and screening. OBG Manag. 2015;27(5):32−39.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):178–182.

- Wright TC, Stoler MH, Behrens CM, Sharma A, Zhang G, Wright TL. Primary cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus: end of study results from the ATHENA study using HPV as the first-line screening test. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136(2):189–197.

In this article

• The success of adoptive T-cell therapy

• Long-term follow-up of primary HPV screening