User login

Diagnosing borderline personality disorder: Avoid these pitfalls

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with impaired psychosocial functioning, reduced quality of life, increased use of health care services, and excess mortality.1 Unfortunately, this disorder is often underrecognized and underdiagnosed, and patients with BPD may not receive an accurate diagnosis for years after first seeking treatment.1 Problems in diagnosing BPD include:

Stigma. Some patients may view the term “borderline” as stigmatizing, as if we are calling these patients borderline human beings. One of the symptoms of BPD is a “markedly and persistently unstable self-image.”2 Such patients do not need a stigmatizing label to worsen their self-image.

Terminology. The word borderline may also imply relatively mild psychiatric symptoms. However, “borderline personality disorder” does not refer to a mild personality disorder. DSM-5 describes potential BPD symptoms as “intense,” “marked,” or “severe,” and 1 of the symptoms is suicidal behavior.2

Symptoms. To meet the criteria for a BPD diagnosis, a patient must exhibit ≥5 of 9 severe symptoms2:

- frantic efforts to avoid abandonment

- unstable and intense interpersonal relationships

- unstable self-image

- impulsivity in ≥2 areas that are potentially self-damaging

- suicidal behavior

- affective instability

- chronic feelings of emptiness

- inappropriate anger

- transient paranoid ideation or dissociative symptoms.

Asking about all 9 of these criteria and their severity is not part of a routine psychiatric evaluation. A patient might not volunteer any of this information because they are concerned about potential stigma. Additionally, perhaps most of the general population has had a “BPD-like” symptom at least once during their lives. This symptom might not have been severe enough to qualify as a true BPD symptom. Clinicians might have difficulty discerning BPD-like symptoms from true BPD symptoms.

Comorbidities. Many patients with BPD also have a comorbid mood disorder or substance use disorder.1,3 Clinicians might focus on a comorbid diagnosis and not recognize BPD.

Stress. BPD symptoms may become more severe when the patient faces a stressful situation. The BPD symptoms might seem more severe than the stress would warrant.2 However, clinicians might blame the BPD symptoms solely on stress and not acknowledge the underlying BPD diagnosis.

Awareness of these factors can help clinicians keep BPD in the differential diagnosis when conducting a psychiatric evaluation, thus reducing the chances of overlooking this serious disorder.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

1. Zimmerman M. Improving the recognition of borderline personality disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(10):13-19.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:663-666.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008:69(4)533-545.

The evolution of manic and hypomanic symptoms

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

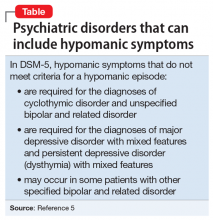

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

Since publication of the first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952,1 the diagnosis of manic and hypomanic symptoms has evolved significantly. This evolution has changed my approach to patients who exhibit these symptoms, which include increased goal-directed activity, decreased need for sleep, and racing thoughts. Here I outline these diagnostic changes in each edition of the DSM and discuss their therapeutic importance and the possibility of future changes.

DSM-I (1952) described manic symptoms as having psychotic features.1 The term “manic episode” was not used, but manic symptoms were described as having a “tendency to remission and recurrence.”1

DSM-II (1968) introduced the term “manic episode” as having psychotic features.2 Manic episodes were characterized by symptoms of excessive elation, irritability, talkativeness, flight of ideas, and accelerated speech and motor activity.2

DSM-III (1980) explained that a manic episode could occur without psychotic features.3 The term “hypomanic episode” was introduced. It described manic features that do not meet criteria for a manic episode.3

DSM-IV (1994) reiterated the criteria for a manic episode.4 In addition, it established criteria for a hypomanic episode as lasting at least 4 days and requires ≥3 symptoms.4

DSM-5 (2013) describes hypomanic symptoms that do not meet criteria for a hypomanic episode (Table).5 These symptoms may require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic medication.5

Suggested changes for the next DSM

Although DSM-5 does not discuss the duration of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient, these can vary widely.6 The same patient may have increased activity for 2 days, increased irritability for 2 weeks, and racing thoughts every day. Future versions of the DSM could include the varying durations of different manic or hypomanic symptoms in the same patient.

Continue to: Racing thoughts without...

Racing thoughts without increased energy or activity occur frequently and often go unnoticed.7 They can be mistaken for severe worrying or obsessive ideation. Depending on the severity of the patient’s racing thoughts, treatment might include a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. All 5 DSM-5 diagnoses listed in the Table5 may include this symptom pattern, but do not specifically mention it. A diagnosis or specifier, such as “racing thoughts without increased energy or activity,” might help clinicians better recognize and treat this symptom pattern.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1952:24-25.

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1968:35-37.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1980:208-210,223.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994:332,338.

5. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013:139-140,148-149,169,184-185.

6. Wilf TJ. When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes. Current Psychiatry. 2012;11(8):55.

7. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59(5):570-575.

Racing thoughts: What to consider

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

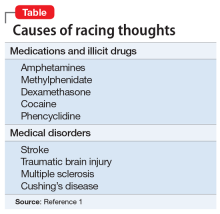

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

Have you ever had times in your life when you had a tremendous amount of energy, like too much energy, with racing thoughts? I initially ask patients this question when evaluating for bipolar disorder. Some patients insist that they have racing thoughts—thoughts occurring at a rate faster than they can be expressed through speech1—but not episodes of hyperactivity. This response suggests that some patients can have racing thoughts without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder.

Among the patients I treat, racing thoughts vary in severity, duration, and treatment. When untreated, a patient’s racing thoughts may range from a mild disturbance lasting a few days to a more severe disturbance occurring daily. In this article, I suggest treatments that may help ameliorate racing thoughts, and describe possible causes that include, but are not limited to, mood disorders.

Major depressive disorder

Many patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) have racing thoughts that often go unrecognized, and this symptom is associated with more severe depression.2 Those with a DSM-5 diagnosis of MDD with mixed features could experience prolonged racing thoughts during a major depressive episode.1 Untreated racing thoughts may explain why many patients with MDD do not improve with an antidepressant alone.3 These patients might benefit from augmentation with a mood stabilizer such as lithium4 or a second-generation antipsychotic.5

Other potential causes

Racing thoughts are a symptom, not a diagnosis. Apprehension and anxiety could cause racing thoughts that do not require treatment with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic. Patients who often worry about having panic attacks or experience severe chronic stress may have racing thoughts. Also, some patients may be taking medications or illicit drugs or have a medical disorder that could cause symptoms of mania or hypomania that include racing thoughts (Table1).

In summary, when caring for a patient who reports having racing thoughts, consider:

- whether that patient actually does have racing thoughts

- the potential causes, severity, duration, and treatment of the racing thoughts

- the possibility that for a patient with MDD, augmenting an antidepressant with a mood stabilizer or antipsychotic could decrease racing thoughts, thereby helping to alleviate many cases of MDD.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Benazzi F. Unipolar depression with racing thoughts: a bipolar spectrum disorder? Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:570-575.

3. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ. Randomized, placebo-controlled trials of antidepressants for acute major depression: thirty-year meta-analytic review. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(4):851-864.

4. Bauer M, Adli M, Bschor T, et al. Lithium’s emerging role in the treatment of refractory major depressive episodes: augmentation of antidepressants. Neuropsychobiology. 2010;62(1):36-42.

5. Nelson JC, Papakostas GI. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):980-991.

The benzodiazepine dilemma

As clinicians, we are faced with a conflict when deciding whether or not to prescribe a benzodiazepine. If we prescribe one of these agents, we might be putting our patients at risk for dependence and abuse. However, if we do not prescribe them, we risk providing inadequate treatment, especially for patients with panic disorder.

Benzodiazepine dependence and abuse can take many forms. Dependence can be psychological as well as physiologic. While many patients will adhere to their prescribing regimen, some may sell their benzodiazepines, falsely claim that they have “panic attacks,” or take a fatal overdose of an opioid and benzodiazepine combination.

Here I discuss the pros and cons of restricting benzodiazepines use to low doses and/or combination therapy with antidepressants.

_

Weighing the benefits of restricted prescribing

Some double-blind studies referenced in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2010 Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder1 suggest that benzodiazepine duration of treatment and dosages should be severely restricted. These studies found that:

- Although the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and a benzodiazepine initially decreased the number of panic attacks more quickly than SSRI monotherapy, the 2 treatments are equally effective after 4 or 5 weeks.2,3

- For the treatment of panic disorder, a low dosage of a benzodiazepine (clonazepam 1 mg/d or alprazolam 2 mg/d) was as effective as a higher dosage (clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 6 mg/d).4,5

However, these studies could be misleading. They all excluded patients with a comorbid condition, such as bipolar disorder or depression, that was more severe than their panic disorder. Severe comorbidity is associated with more severe panic symptoms,6,7 which might require an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination or a higher benzodiazepine dosage.

The APA Practice Guideline suggests the following possible options:

- benzodiazepine augmentation if there is a partial response to an SSRI

- substitution with a different SSRI or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) if there is no response to an SSRI

- benzodiazepine augmentation or substitution if there is still no therapeutic response.

Continue to: The APA Practice Guideline also states...

The APA Practice Guideline also states that although the highest “usual therapeutic dose” for panic disorder is clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 4 mg/d, “higher doses are sometimes used for patients who do not respond to the usual therapeutic dose.”1

Presumably, an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination should be considered if an SSRI alleviates major depressive disorder but does not alleviate a comorbid panic disorder. However, the APA Practice Guideline does not include studies that investigated this clinical scenario.

Monitor carefully for dependency/abuse

Restricting benzodiazepine use to low doses over a short period of time may decrease the risk of dependence and abuse. However, this practice may also limit or prevent effective treatment for adherent patients with panic disorder who do not adequately respond to SSRI or SNRI monotherapy.

Therefore, clinicians need to carefully differentiate between patients who are adherent to their prescribed dosages and those who may be at risk for benzodiazepine dependence and abuse. Consider using prescription drug monitoring programs and drug screens to help detect patients who “doctor shop” for benzodiazepines, or who could be abusing opioids, alcohol, marijuana, or other substances while taking a benzodiazepine.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2010. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-686.

3. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(3):276-282.

4. Lydiard RB, Lesser IM, Ballenger JC, et al. A fixed-dose study of alprazolam 2 mg, alprazolam 6 mg, and placebo in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12(2):966-103.

5. Rosenbaum JF, Moroz G, Bowden CL. Clonazepam in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a dose-response study of efficacy, safety, and discontinuance. Clonazepam Panic Disorder Dose-Response Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(5):390-400.

6. Goodwin RD, Hoven CW. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2002;70(1):27-33.

7. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, et al. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:229-235.

As clinicians, we are faced with a conflict when deciding whether or not to prescribe a benzodiazepine. If we prescribe one of these agents, we might be putting our patients at risk for dependence and abuse. However, if we do not prescribe them, we risk providing inadequate treatment, especially for patients with panic disorder.

Benzodiazepine dependence and abuse can take many forms. Dependence can be psychological as well as physiologic. While many patients will adhere to their prescribing regimen, some may sell their benzodiazepines, falsely claim that they have “panic attacks,” or take a fatal overdose of an opioid and benzodiazepine combination.

Here I discuss the pros and cons of restricting benzodiazepines use to low doses and/or combination therapy with antidepressants.

_

Weighing the benefits of restricted prescribing

Some double-blind studies referenced in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2010 Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder1 suggest that benzodiazepine duration of treatment and dosages should be severely restricted. These studies found that:

- Although the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and a benzodiazepine initially decreased the number of panic attacks more quickly than SSRI monotherapy, the 2 treatments are equally effective after 4 or 5 weeks.2,3

- For the treatment of panic disorder, a low dosage of a benzodiazepine (clonazepam 1 mg/d or alprazolam 2 mg/d) was as effective as a higher dosage (clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 6 mg/d).4,5

However, these studies could be misleading. They all excluded patients with a comorbid condition, such as bipolar disorder or depression, that was more severe than their panic disorder. Severe comorbidity is associated with more severe panic symptoms,6,7 which might require an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination or a higher benzodiazepine dosage.

The APA Practice Guideline suggests the following possible options:

- benzodiazepine augmentation if there is a partial response to an SSRI

- substitution with a different SSRI or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) if there is no response to an SSRI

- benzodiazepine augmentation or substitution if there is still no therapeutic response.

Continue to: The APA Practice Guideline also states...

The APA Practice Guideline also states that although the highest “usual therapeutic dose” for panic disorder is clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 4 mg/d, “higher doses are sometimes used for patients who do not respond to the usual therapeutic dose.”1

Presumably, an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination should be considered if an SSRI alleviates major depressive disorder but does not alleviate a comorbid panic disorder. However, the APA Practice Guideline does not include studies that investigated this clinical scenario.

Monitor carefully for dependency/abuse

Restricting benzodiazepine use to low doses over a short period of time may decrease the risk of dependence and abuse. However, this practice may also limit or prevent effective treatment for adherent patients with panic disorder who do not adequately respond to SSRI or SNRI monotherapy.

Therefore, clinicians need to carefully differentiate between patients who are adherent to their prescribed dosages and those who may be at risk for benzodiazepine dependence and abuse. Consider using prescription drug monitoring programs and drug screens to help detect patients who “doctor shop” for benzodiazepines, or who could be abusing opioids, alcohol, marijuana, or other substances while taking a benzodiazepine.

As clinicians, we are faced with a conflict when deciding whether or not to prescribe a benzodiazepine. If we prescribe one of these agents, we might be putting our patients at risk for dependence and abuse. However, if we do not prescribe them, we risk providing inadequate treatment, especially for patients with panic disorder.

Benzodiazepine dependence and abuse can take many forms. Dependence can be psychological as well as physiologic. While many patients will adhere to their prescribing regimen, some may sell their benzodiazepines, falsely claim that they have “panic attacks,” or take a fatal overdose of an opioid and benzodiazepine combination.

Here I discuss the pros and cons of restricting benzodiazepines use to low doses and/or combination therapy with antidepressants.

_

Weighing the benefits of restricted prescribing

Some double-blind studies referenced in the American Psychiatric Association (APA) 2010 Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Panic Disorder1 suggest that benzodiazepine duration of treatment and dosages should be severely restricted. These studies found that:

- Although the combination of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and a benzodiazepine initially decreased the number of panic attacks more quickly than SSRI monotherapy, the 2 treatments are equally effective after 4 or 5 weeks.2,3

- For the treatment of panic disorder, a low dosage of a benzodiazepine (clonazepam 1 mg/d or alprazolam 2 mg/d) was as effective as a higher dosage (clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 6 mg/d).4,5

However, these studies could be misleading. They all excluded patients with a comorbid condition, such as bipolar disorder or depression, that was more severe than their panic disorder. Severe comorbidity is associated with more severe panic symptoms,6,7 which might require an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination or a higher benzodiazepine dosage.

The APA Practice Guideline suggests the following possible options:

- benzodiazepine augmentation if there is a partial response to an SSRI

- substitution with a different SSRI or a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) if there is no response to an SSRI

- benzodiazepine augmentation or substitution if there is still no therapeutic response.

Continue to: The APA Practice Guideline also states...

The APA Practice Guideline also states that although the highest “usual therapeutic dose” for panic disorder is clonazepam 2 mg/d or alprazolam 4 mg/d, “higher doses are sometimes used for patients who do not respond to the usual therapeutic dose.”1

Presumably, an SSRI/benzodiazepine combination should be considered if an SSRI alleviates major depressive disorder but does not alleviate a comorbid panic disorder. However, the APA Practice Guideline does not include studies that investigated this clinical scenario.

Monitor carefully for dependency/abuse

Restricting benzodiazepine use to low doses over a short period of time may decrease the risk of dependence and abuse. However, this practice may also limit or prevent effective treatment for adherent patients with panic disorder who do not adequately respond to SSRI or SNRI monotherapy.

Therefore, clinicians need to carefully differentiate between patients who are adherent to their prescribed dosages and those who may be at risk for benzodiazepine dependence and abuse. Consider using prescription drug monitoring programs and drug screens to help detect patients who “doctor shop” for benzodiazepines, or who could be abusing opioids, alcohol, marijuana, or other substances while taking a benzodiazepine.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2010. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-686.

3. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(3):276-282.

4. Lydiard RB, Lesser IM, Ballenger JC, et al. A fixed-dose study of alprazolam 2 mg, alprazolam 6 mg, and placebo in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12(2):966-103.

5. Rosenbaum JF, Moroz G, Bowden CL. Clonazepam in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a dose-response study of efficacy, safety, and discontinuance. Clonazepam Panic Disorder Dose-Response Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(5):390-400.

6. Goodwin RD, Hoven CW. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2002;70(1):27-33.

7. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, et al. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:229-235.

1. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder, 2nd edition. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2010. https://psychiatryonline.org/pb/assets/raw/sitewide/practice_guidelines/guidelines/panicdisorder.pdf. Accessed March 7, 2018.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(7):681-686.

3. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17(3):276-282.

4. Lydiard RB, Lesser IM, Ballenger JC, et al. A fixed-dose study of alprazolam 2 mg, alprazolam 6 mg, and placebo in panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1992;12(2):966-103.

5. Rosenbaum JF, Moroz G, Bowden CL. Clonazepam in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia: a dose-response study of efficacy, safety, and discontinuance. Clonazepam Panic Disorder Dose-Response Study Group. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1997;17(5):390-400.

6. Goodwin RD, Hoven CW. Bipolar-panic comorbidity in the general population: prevalence and associated morbidity. J Affect Disord. 2002;70(1):27-33.

7. Roy-Byrne PP, Stang P, Wittchen HU, et al. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Association with symptoms, impairment, course and help-seeking. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:229-235.

When to treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes

According to DSM-IV-TR, the minimal duration of a hypomanic episode is 4 days.1 Should we treat patients for hypomanic symptoms that last <4 days? Could antidepressants’ high failure rate2 be because many depressed patients have untreated “subthreshold hypomanic episodes”? Aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lithium all have been shown to alleviate depression when added to an antidepressant.3-5 Is it possible that these medications are treating subthreshold hypomanic episodes rather than depression?

The literature does not answer these questions. To further confuse matters, a subthreshold hypomanic episode may not be a discrete episode. In such episodes, hypomanic symptoms may overlap at some point and the duration of each symptom may vary.

When I administer the Mood Disorder Questionnaire,6,7 I ask patients about 13 hypomanic symptoms. Patient responses to questions about 7 of these symptoms—increased energy, irritability, talking, and activity, feeling “hyper,” racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep—can help demonstrate the variability of symptom duration. For example, a patient may complain of increased energy and irritability for 3 days, increased activity and feeling “hyper” for 2 days, increased talking and a decreased need to sleep for 1 day, and racing thoughts every day.

Alternative criteria

Considering this variation, I often use the following criteria when considering whether to treat subthreshold hypomanic symptoms:

- ≥4 symptoms must last ≥2 consecutive days

- ≥3 symptoms must overlap at some point, and

- ≥2 of the symptoms must be increased energy, increased activity, or racing thoughts.

However, some patients have hypomanic symptoms that do not meet these relaxed criteria but require treatment.8 I also need to know when these episodes started, how frequently they occur, and how much of a problem they cause in the patient’s life. I often treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes with an antipsychotic or a mood stabilizer. As with all patients I see, I consider the patient’s reliability, substance abuse history, and mental status during the interview.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Pigott HE, Leventhal AM, Alter GS, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: current status of research. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(5):267-279.

3. Nelson JC, Pikalov A, Berman RM. Augmentation treatment in major depressive disorder: focus on aripiprazole. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(5):937-948.

4. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH. A review of quetiapine in combination with antidepressant therapy in patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(6):855-867.

5. Price LH, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR. Lithium augmentation for refractory depression: a critical reappraisal. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(11):35-42.

6. Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1873-1875.

7. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. http://www.drpaddison.com/mood.pdf. Accessed June 20 2012.

8. Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed bipolar disorders in patients with a major depressive episode: the BRIDGE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):791-798.

According to DSM-IV-TR, the minimal duration of a hypomanic episode is 4 days.1 Should we treat patients for hypomanic symptoms that last <4 days? Could antidepressants’ high failure rate2 be because many depressed patients have untreated “subthreshold hypomanic episodes”? Aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lithium all have been shown to alleviate depression when added to an antidepressant.3-5 Is it possible that these medications are treating subthreshold hypomanic episodes rather than depression?

The literature does not answer these questions. To further confuse matters, a subthreshold hypomanic episode may not be a discrete episode. In such episodes, hypomanic symptoms may overlap at some point and the duration of each symptom may vary.

When I administer the Mood Disorder Questionnaire,6,7 I ask patients about 13 hypomanic symptoms. Patient responses to questions about 7 of these symptoms—increased energy, irritability, talking, and activity, feeling “hyper,” racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep—can help demonstrate the variability of symptom duration. For example, a patient may complain of increased energy and irritability for 3 days, increased activity and feeling “hyper” for 2 days, increased talking and a decreased need to sleep for 1 day, and racing thoughts every day.

Alternative criteria

Considering this variation, I often use the following criteria when considering whether to treat subthreshold hypomanic symptoms:

- ≥4 symptoms must last ≥2 consecutive days

- ≥3 symptoms must overlap at some point, and

- ≥2 of the symptoms must be increased energy, increased activity, or racing thoughts.

However, some patients have hypomanic symptoms that do not meet these relaxed criteria but require treatment.8 I also need to know when these episodes started, how frequently they occur, and how much of a problem they cause in the patient’s life. I often treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes with an antipsychotic or a mood stabilizer. As with all patients I see, I consider the patient’s reliability, substance abuse history, and mental status during the interview.

According to DSM-IV-TR, the minimal duration of a hypomanic episode is 4 days.1 Should we treat patients for hypomanic symptoms that last <4 days? Could antidepressants’ high failure rate2 be because many depressed patients have untreated “subthreshold hypomanic episodes”? Aripiprazole, quetiapine, and lithium all have been shown to alleviate depression when added to an antidepressant.3-5 Is it possible that these medications are treating subthreshold hypomanic episodes rather than depression?

The literature does not answer these questions. To further confuse matters, a subthreshold hypomanic episode may not be a discrete episode. In such episodes, hypomanic symptoms may overlap at some point and the duration of each symptom may vary.

When I administer the Mood Disorder Questionnaire,6,7 I ask patients about 13 hypomanic symptoms. Patient responses to questions about 7 of these symptoms—increased energy, irritability, talking, and activity, feeling “hyper,” racing thoughts, and decreased need for sleep—can help demonstrate the variability of symptom duration. For example, a patient may complain of increased energy and irritability for 3 days, increased activity and feeling “hyper” for 2 days, increased talking and a decreased need to sleep for 1 day, and racing thoughts every day.

Alternative criteria

Considering this variation, I often use the following criteria when considering whether to treat subthreshold hypomanic symptoms:

- ≥4 symptoms must last ≥2 consecutive days

- ≥3 symptoms must overlap at some point, and

- ≥2 of the symptoms must be increased energy, increased activity, or racing thoughts.

However, some patients have hypomanic symptoms that do not meet these relaxed criteria but require treatment.8 I also need to know when these episodes started, how frequently they occur, and how much of a problem they cause in the patient’s life. I often treat subthreshold hypomanic episodes with an antipsychotic or a mood stabilizer. As with all patients I see, I consider the patient’s reliability, substance abuse history, and mental status during the interview.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Pigott HE, Leventhal AM, Alter GS, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: current status of research. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(5):267-279.

3. Nelson JC, Pikalov A, Berman RM. Augmentation treatment in major depressive disorder: focus on aripiprazole. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(5):937-948.

4. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH. A review of quetiapine in combination with antidepressant therapy in patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(6):855-867.

5. Price LH, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR. Lithium augmentation for refractory depression: a critical reappraisal. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(11):35-42.

6. Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1873-1875.

7. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. http://www.drpaddison.com/mood.pdf. Accessed June 20 2012.

8. Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed bipolar disorders in patients with a major depressive episode: the BRIDGE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):791-798.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

2. Pigott HE, Leventhal AM, Alter GS, et al. Efficacy and effectiveness of antidepressants: current status of research. Psychother Psychosom. 2010;79(5):267-279.

3. Nelson JC, Pikalov A, Berman RM. Augmentation treatment in major depressive disorder: focus on aripiprazole. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4(5):937-948.

4. Daly EJ, Trivedi MH. A review of quetiapine in combination with antidepressant therapy in patients with depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(6):855-867.

5. Price LH, Carpenter LL, Tyrka AR. Lithium augmentation for refractory depression: a critical reappraisal. Prim Psychiatry. 2008;15(11):35-42.

6. Hirschfeld RM, Williams JB, Spitzer RL, et al. Development and validation of a screening instrument for bipolar spectrum disorder: the Mood Disorder Questionnaire. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1873-1875.

7. The Mood Disorder Questionnaire. http://www.drpaddison.com/mood.pdf. Accessed June 20 2012.

8. Angst J, Azorin JM, Bowden CL, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of undiagnosed bipolar disorders in patients with a major depressive episode: the BRIDGE study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(8):791-798.

Pharmacotherapy for panic disorder: Clinical experience vs the literature

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Clinical experiences sometimes contradict the psychiatric literature. For example, some of my patients with panic disorder (PD) benefit from adding benzodiazepines to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). However, 2 double-blind studies show that adding benzodiazepines to SSRIs does not help PD patients.1,2 Why are my patients different from those in the studies? Some of my patients may have been misusing benzodiazepines or were psychologically habituated to them, but I doubt that explains all of the improvement I observed.

A more relevant reason for the different responses seen in my patients and those in the 2 studies may be differences in the populations involved. For example, many of my PD patients had not responded to SSRIs alone. In contrast, none of the patients in the studies had been unresponsive to SSRIs.

Also, unlike patients in the studies, many of my patients with PD have severe psychiatric comorbidity—they also may have a diagnosis of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, or depression. Comorbidity may affect the severity of PD and treatment response. For example, PD with recurrent comorbid depression has been shown to be more difficult to treat, suggesting the need for “combination treatment with SSRI and benzodiazepines or with pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavior therapy.”3

I am not suggesting that benzodiazepines should be added to SSRIs for every patient with PD and severe comorbidity. Some of my patients with PD and comorbid psychiatric disorders do quite well with SSRIs alone. I suggest that patients who do not respond to SSRIs may benefit from adjunctive benzodiazepines. Severe comorbidity may suggest the need for adding benzodiazepines; the lack of response to high doses of SSRIs also may be a determining factor.

Disclosure: Dr Wilf reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.

1. Pollack MH, Simon NM, Worthington JJ, et al. Combined paroxetine and clonazepam treatment strategies compared to paroxetine monotherapy for panic disorder. J Psychopharmacol. 2003;17:276-282.

2. Goddard AW, Brouette T, Almai A, et al. Early coadministration of clonazepam with sertraline for panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:681-686.

3. Marchesi C, Cantoni A, Fonto S, et al. Predictors of symptom resolution in panic disorder after one year of pharmacological treatment: a naturalistic study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2006;39:60-65.