User login

New-onset epilepsy in the elderly: Challenges for the internist

Contrary to the popular belief that epilepsy is mainly a disease of youth, nearly 25% of new-onset seizures occur after age 65.1,2 The incidence of epilepsy in this age group is almost twice the rate in children, and in people over age 80, it is triple the rate in children.3 As our population ages, the burden of “elderly-onset” epilepsy will rise.

A seizure diagnosis carries significant implications in older people, who are already vulnerable to cognitive decline, loss of functional independence, driving restrictions, and risk of falls. Newly diagnosed epilepsy further worsens quality of life.4

The causes and clinical manifestations of seizures and epilepsy in the elderly differ from those in younger people.5 Hence, it is often difficult to make a diagnosis with certainty from a wide range of differential diagnoses. Older people are also more likely to have comorbidities, further complicating the situation.

Managing seizures in the elderly is also challenging, as age-associated physiologic changes can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs. Diagnosing and managing elderly-onset epilepsy can be challenging for a family physician, an internist, a geriatrician, or even a neurologist.

In this review, we emphasize the common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly and the assessment of the clinical clues that are essential for making an accurate diagnosis. We also review the pharmacology of antiepileptic drugs used in old age and highlight the need for psychological support for patients and caregivers.

RISING PREVALENCE IN THE ELDERLY

In US Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older, the average annual incidence rate of epilepsy in 2001 to 2005 was 10.8 per 1,000.6 A large study in Finland revealed falling incidence rates of epilepsy in childhood and middle age and rising trends in the elderly.7

In the United States, the rates are higher in African Americans (18.7 per 1,000) and lower in Asian Americans and Native Americans (5.5 and 7.7 per 1,000) than in whites (10.2 per 1,000).6 Incidence rates are slightly higher for women than for men and increase with age in both sexes and all racial groups.

Acute symptomatic seizure is also common in older patients. The incidence of acute seizures in patients over age 60 was estimated at 50 to 100 per 100,000 per year in one study.7 The rate was considerably higher in men than in women. The study also found a 3.6% risk of experiencing an acute symptomatic seizure in an 80-year lifespan, which approaches that of developing epilepsy.8 The major causes of acute symptomatic seizure were traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular disease, drug withdrawal, and central nervous system infection.

CAUSES OF NEW-ONSET EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

The most common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly include cerebrovascular disease, metabolic disturbances, dementia, traumatic brain injury, tumors, and drugs.3,9–11

Cerebrovascular disease

In older adults, acute stroke is the most common cause, accounting for up to half of cases.5,12

Seizures occur in 4.4% to 8.9% of acute cerebrovascular events.13,14 The risk varies by stroke subtype, although all stroke subtypes, including transient ischemic attack, can be associated with seizure.15 For example, although 1% to 2% of patients experienced a seizure within 15 days of a transient ischemic attack or a lacunar infarct, this risk was 16.6% after an embolic stroke.15

Beyond this increased risk of “acute seizure” in the immediate poststroke period (usually defined as 1 week), the risk of epilepsy was also 20 times higher in the first year after a stroke.14 However, seizures tend to occur within the first 48 hours after the onset of ischemic stroke. In subarachnoid hemorrhage, seizures generally occur within hours.16

In a population-based study in Rochester, NY,17 epilepsy developed in two-thirds of patients with seizure related to acute stroke. Two factors that independently predicted the development of epilepsy were early seizure occurrence and recurrence of stroke.

Interestingly, the risk of stroke was three times higher in older patients who had new-onset seizure.18 Therefore, any elderly person with new-onset seizure should be assessed for cerebrovascular risk factors and treated accordingly for stroke prevention.

Metabolic disturbances

Acute metabolic disorders are common in elderly patients because of multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy. Hypoglycemia and hyponatremia need to be particularly considered in this population.19

Other well-documented metabolic causes of acute seizure, including nonketotic hyperglycemia, hypocalcemia, and uremic or hepatic encephalopathy, can all be considerations, albeit less specific to this age group.

Dementia

Primary neurodegenerative disorders associated with cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer disease, are major risk factors for new-onset epilepsy in older patients.3,5 Seizures occur in about 10% of Alzheimer patients.20 Those who have brief periods of increased confusion may actually be experiencing unrecognized complex partial seizures.21

A case-control study discovered incidence rates of epilepsy almost 10 times higher in patients who had Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia than in nondemented patients.22 A prospective cohort study in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease established that younger age, a greater degree of cognitive impairment, and a history of antipsychotic use were independent risk factors for new-onset seizures in the elderly.23 Preexisting dementia also increases the risk of poststroke epilepsy.24

Traumatic brain injury

The most common cause of brain trauma in the elderly is falls. Subdural hematoma, which can occur in the elderly with trivial trauma or sometimes even without it, needs to be considered. The risk of posttraumatic hemorrhage is especially relevant in patients taking anticoagulants.

Traumatic brain injury has a poorer prognosis in older people than in the young,25 and it accounts for up to 20% of cases of epilepsy in the elderly.26 Although no study has specifically addressed the longitudinal risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in the elderly, a study in children and young adults revealed the risk was highest in the first year, with the increased risk persisting for more than 10 years.27

Brain tumors

Between 10% and 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly are associated with tumor, typically glioma, meningioma, and brain metastasis.28,29 Seizures are usually associated more with primary than with secondary tumors, and more with low-grade tumors than high-grade ones.30

Drug-induced

Drugs and drug withdrawal can contribute to up to 10% of acute symptomatic seizures in the geriatric population.5,8,29 The elderly are susceptible to drug-induced seizure because of a higher prevalence of polypharmacy, impaired drug clearance, and heightened sensitivity to the proconvulsant side effects of medications.1 A number of commonly used drugs have been implicated,31 including:

Antibiotics such as carbapenems and high-dose penicillin

Antihistamines such as desloratadine (Clarinex)

Pain medications such as tramadol (Ul-tram) and high-dose opiates

Neuromodulators

Antidepressants such as clomipramine (Anafranil), maprotiline (Ludiomil), amoxapine (Asendin), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).32

Seizures also follow alcohol, benzodiazepine, and barbiturate withdrawal.33

Other causes

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis is a rare cause of seizures in the elderly.34 It can present with refractory seizures, confusion, and behavioral changes with or without a known concurrent neoplastic disease.

Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome, another rare consideration, can particularly affect immunosuppressed elderly patients. This syndrome is characterized clinically by headache, confusion, seizures, vomiting, and visual disturbances with radiographic vasogenic edema.35

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The signs and symptoms of a seizure may be atypical in the elderly. Seizures more often have a picture of “epileptic amnesia,” with confusion, sleepiness, or clumsiness, rather than motor manifestations such as tonic stiffening or automatism.36,37 Postictal states are also prolonged, particularly if there is underlying brain dysfunction.38 All these features render the clinical seizure manifestations more subtle and, as such, more difficult for the uninitiated caregiver to identify.

Convulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as a single generalized seizure lasting more than 5 minutes or a series of seizures lasting longer than 30 minutes without the patient’s regaining consciousness.39 The greatest increase in the incidence of status epilepticus occurs after age 60.40 It is the first seizure in about 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly.41

Mortality rates increase with age, anoxia, and duration of status epilepticus and are over 50% in patients age 80 and older.40,42

Convulsive status epilepticus is most commonly caused by stroke.40

Absence status epilepticus can occur in elderly patients as a late complication of idiopathic generalized epilepsy related to benzodiazepine withdrawal, alcohol intoxication, or initiation of psychotropic drugs.42

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus manifests as altered mental status, psychosis, lethargy, or coma.42–44 Occasionally, it presents as a more focal cognitive disturbance with aphasia or a neglect syndrome.42,45 Electroencephalographic correlates of nonconvulsive status epilepticus include focal rhythmic discharges, often arising from frontal or temporal lobes, or generalized spike or sharp and slow-wave activity.46 Its management is challenging because of delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. The risk of death is higher in patients with severely impaired mental status or acute complications.47

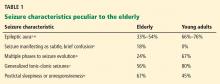

Table 1 lists the typical seizure manifestations peculiar to the elderly.37,48

Differential diagnosis of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly

New-onset epilepsy in elderly patients can be confused with syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac arrhythmia, metabolic disturbances, transient global amnesia, neurodegenerative disease, rapid-eye-movement sleep behavior disorder, psychogenic disorders, and other conditions (Table 2). If there is a high clinical suspicion of seizure, the patient should undergo electroencephalography (EEG) and be referred to a neurologist or epileptologist.

KEYS TO THE DIAGNOSIS

Clinical history

A reliable history and description of the event from an eyewitness or a video recording of the event are invaluable to the diagnosis of epileptic seizure. Signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis include aura, ictal pallor, urinary incontinence, tongue-biting, and motor symptoms, as well as postictal confusion, drowsiness, and speech disturbance.

Electroencephalography

EEG is the most useful diagnostic tool in epilepsy. However, an interictal EEG reading (ie, between epileptic attacks) in an elderly patient has limited utility, showing epileptiform activity in only about one-fourth of patients.49 Nonspecific EEG abnormalities such as intermittent focal slowing are seen in many older people even without seizure.50 Also, normal findings on outpatient EEG do not rule out epilepsy, as EEG is normal in about one-third of patients with epilepsy, irrespective of age.1,49 Activation procedures such as hyperventilation and photic stimulation add little to the diagnosis in the elderly.49

On the other hand, video-EEG monitoring is an excellent tool for evaluating possible epilepsy, as it allows accurate assessment of brain electrical activity during the events in question. Moreover, studies of video-EEG recording of seizures in elderly patients demonstrated epileptiform discharges on EEG in 76% of clinical ictal events.50

Therefore, routine EEG is a useful screening tool, and inpatient video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard to characterize events of concern and distinguish between epileptic and nonepileptic or psychogenic seizures.

Other diagnostic studies

Brain imaging, preferably magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, should be done in every patient with possible epilepsy due to stroke, traumatic brain injury, or other structural brain disease.51

Electrocardiography helps exclude cardiac causes such as arrhythmia.

Blood testing. Metabolically provoked seizure can be distinguished by blood analysis for electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, calcium, magnesium, liver enzymes, and drug levels (eg, ethanol). A complete blood cell count with differential and platelets should also be done in anticipation of starting antiepileptic drug therapy.

Lumbar puncture for cell count, protein, glucose, stains, and cultures should be performed whenever meningitis or encephalitis is suspected.

A sleep study with concurrent video-EEG monitoring may be required to distinguish epileptic seizures from sleep disorders.

Neuropsychological testing may help account for the degree of cognitive impairment present.

Risk factors for stroke should be assessed in every elderly person who has new-onset seizures, because the risk of stroke is high.17

Figure 1 shows the workup for an elderly patient with suspected new-onset epilepsy.

TREATING EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

Therapeutic challenges

Age-associated changes in drug absorption, protein binding, and distribution in body compartments require adjustments in drug selection and dosage. The causes and manifestations of these changes are typically multifactorial, mainly related to altered metabolism, declining plasma albumin concentrations, and increasing competition for protein binding by concomitantly used drugs.

The differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs depend on the patient’s physical status, relevant comorbidities, and concomitant medications.52 Renal and hepatic function may decline in an elderly patient; accordingly, precaution is needed in the prescribing and dosing of antiepileptic drugs.

Adverse effects from seizure medications are twice as common in elderly patients compared with younger patients. Ataxia, tremor, visual disturbance, and sedation are the most common.1 Antiepileptic drugs are also harmful to bone; induced abnormalities in bone metabolism include hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, decreased levels of active vitamin D metabolites, and hyperparathyroidism.53

Elderly patients tend to take multiple drugs, and some drugs can lower the seizure threshold, particularly antidepressants, anti-psychotics, and antibiotics.32 The herbal remedy ginkgo biloba can also precipitate seizure in this population.54

Antiepileptic drugs such as phenobarbital, primidone (Mysoline), phenytoin (Dilantin), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) can be broad-spectrum enzyme-inducers, increasing the metabolism of many drugs, including warfarin (Coumadin), cytotoxic agents, statins, cardiac antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.55 For example, carbamazepine can alter the metabolism of several hepatically metabolized drugs and cause significant hyponatremia. This is problematic in patients already taking sodium-depleting antihypertensives. Age-related cognitive decline can worsen the situation, often leading to misdiagnosis or patient noncompliance.

Table 3 profiles the interactions of commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

The ideal pharmacotherapy

No single drug is ideal for elderly patients with new-onset epilepsy. The choice mostly depends on the type of seizure and the patient’s comorbidities. The ideal antiepileptic drug would have minimal enzyme interaction, little protein binding, linear kinetics, a long half-life, a good safety profile, and a high therapeutic index. The goal of management should be to maintain the patient’s normal lifestyle with complete control of seizures and with minimal side effects.

The only randomized controlled trial in new-onset geriatric epilepsy concluded that gabapentin (Neurontin) and lamotrigine (Lamictal) should be the initial therapy in such patients.56 Trials indicate extended-release carbamazepine or levetiracetam (Keppra) can also be tried.57

The prescribing strategy includes lower initial dose, slower titration, and a lower target dose than for younger patients. Intense monitoring of dosing and drug levels is necessary to avoid toxicity. If the first drug is not tolerated well, another should be substituted. If seizures persist despite increasing dosage, a drug with a different mechanism of action should be tried.58 A patient with drug-resistant epilepsy (failure to respond to two adequate and appropriate antiepileptic drug trials59) should be referred to an epilepsy surgical center for reevaluation and consideration of epilepsy surgery.

Patient and caregiver support is an essential component of management. New-onset epilepsy in the elderly has a significant effect on quality of life, more so if the patient is already cognitively impaired. It erodes self-confidence, survival becomes difficult, and the condition is worse for patients who live alone. Driving restrictions further limit independence and increase isolation. Hence, psychological support programs can significantly boost the self-esteem and morale of such patients and their caregivers.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATION: EPILEPSY IN THE NURSING HOME

Certain points apply to the growing proportion of elderly who reside in nursing homes:

- Several studies in the United States and in Europe60–62 suggest that this subgroup is at higher risk of polypharmacy and more likely to be treated with older antiepileptic drugs.

- Only a minority of these patients (as low as 42% in one study60) received adequate monitoring of antiepileptic drug levels.

- The clinical characteristics and epileptic etiologies of these patients are less well defined.

Together, these observations highlight a particularly vulnerable population, at risk for medication toxicity as well as for undertreatment.

OUR KNOWLEDGE IS STILL GROWING

New-onset epilepsy, although common in the elderly, is difficult to diagnose because of its atypical presentation, concomitant cognitive impairment, and nonspecific abnormalities in routine investigations. But knowledge of its common causes and differential diagnoses makes the task easier. A high suspicion warrants referral to a neurologist or epileptologist.

Challenges to the management of seizures in the elderly include deranged physiologic processes, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy. No single drug is ideal for antiepileptic therapy in the elderly; the choice of drug is usually dictated by seizure type, comorbidities, and tolerance level. The treatment regimen in the elderly is more conservative, and the target dosage is lower than for younger adults. Emotional support of patient and caregivers should be an important aspect of management.

Our knowledge about new-onset epilepsy in the elderly is still growing, and future research should explore its diagnosis, treatment strategies, and care-delivery models.

- Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology 2004; 62(suppl 2):S24–S29.

- Sander JW, Hart YM, Johnson AL, Shorvon SD. National General Practice Study of Epilepsy: newly diagnosed epileptic seizures in a general population. Lancet 1990; 336:1267–1271.

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1993; 34:453–468.

- Laccheo I, Ablah E, Heinrichs R, Sadler T, Baade L, Liow K. Assessment of quality of life among the elderly with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008; 12:257–261.

- Stephen LJ, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000; 355:1441–1446.

- Faught E, Richman J, Martin R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy among older US Medicare beneficiaries. Neurology 2012; 78:448–453.

- Sillanpää M, Lastunen S, Helenius H, Schmidt D. Regional differences and secular trends in the incidence of epilepsy in Finland: a nationwide 23-year registry study. Epilepsia 2011; 52:1857–1867.

- Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Lee JR, Rocca WA. Incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1995; 36:327–333.

- Lühdorf K, Jensen LK, Plesner AM. Etiology of seizures in the elderly. Epilepsia 1986; 27:458–463.

- Granger N, Convers P, Beauchet O, et al. First epileptic seizure in the elderly: electroclinical and etiological data in 341 patients [in French]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2002; 158:1088–1095.

- Pugh MJ, Knoefel JE, Mortensen EM, Amuan ME, Berlowitz DR, Van Cott AC. New-onset epilepsy risk factors in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57:237–242.

- Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8:1019–1030.

- Bladin CF, Alexandrov AV, Bellavance A, et al. Seizures after stroke: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:1617–1622.

- Kilpatrick CJ, Davis SM, Tress BM, Rossiter SC, Hopper JL, Vandendriesen ML. Epileptic seizures in acute stroke. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:157–160.

- Giroud M, Gras P, Fayolle H, André N, Soichot P, Dumas R. Early seizures after acute stroke: a study of 1,640 cases. Epilepsia 1994; 35:959–964.

- Asconapé JJ, Penry JK. Poststroke seizures in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 1991; 7:483–492.

- So EL, Annegers JF, Hauser WA, O’Brien PC, Whisnant JP. Population-based study of seizure disorders after cerebral infarction. Neurology 1996; 46:350–355.

- Cleary P, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Late-onset seizures as a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet 2004; 363:1184–1186.

- Loiseau P. Pathologic processes in the elderly and their association with seizures. In:Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, editors. Seizures and epilepsy in the elderly. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997:63–86.

- Hauser WA, Morris ML, Heston LL, Anderson VE. Seizures and myoclonus in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1986; 36:1226–1230.

- Leppik IE, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1184:208–224.

- Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Schuerch M, Jick SS, Meier CR. Seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia: a population-based nested case-control analysis. Epilepsia 2013; 54:700–707.

- Irizarry MC, Jin S, He F, et al. Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2012; 69:368–372.

- Cordonnier C, Hénon H, Derambure P, Pasquier F, Leys D. Influence of pre-existing dementia on the risk of post-stroke epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76:1649–1653.

- Bruns J, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2003; 44(suppl 10):2–10.

- Hiyoshi T, Yagi K. Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia 2000; 41(suppl 9):31–35.

- Christensen J, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Sidenius P, Olsen J, Vestergaard M. Long-term risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in children and young adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2009; 373:1105–1110.

- Roberts MA, Godfrey JW, Caird FI. Epileptic seizures in the elderly: I. Aetiology and type of seizure. Age Ageing 1982; 11:24–28.

- Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Duché B, Guyot M, Dartigues JF, Aublet B. A survey of epileptic disorders in southwest France: seizures in elderly patients. Ann Neurol 1990; 27:232–237.

- Lote K, Stenwig AE, Skullerud K, Hirschberg H. Prevalence and prognostic significance of epilepsy in patients with gliomas. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34:98–102.

- Franson KL, Hay DP, Neppe V, et al. Drug-induced seizures in the elderly. Causative agents and optimal management. Drugs Aging 1995; 7:38–48.

- Starr P, Klein-Schwartz W, Spiller H, Kern P, Ekleberry SE, Kunkel S. Incidence and onset of delayed seizures after overdoses of extended-release bupropion. Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27:911–915.

- Hauser WA, Ng SK, Brust JC. Alcohol, seizures, and epilepsy. Epilepsia 1988; 29(suppl 2):S66–S78.

- Petit-Pedrol M, Armangue T, Peng X, et al. Encephalitis with refractory seizures, status epilepticus, and antibodies to the GABAA receptor: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:276–286.

- Ait S, Gilbert T, Cotton F, Bonnefoy M. Cortical blindness and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in an older patient. BMJ Case Rep 2012;pii:bcr0920114782.

- Tinuper P, Provini F, Marini C, et al. Partial epilepsy of long duration: changing semiology with age. Epilepsia 1996; 37:162–164.

- Silveira DC, Jehi L, Chapin J, et al. Seizure semiology and aging. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 20:375–377.

- Theodore WH. The postictal state: effects of age and underlying brain dysfunction. Epilepsy Behav 2010; 19:118–120.

- Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:970–976.

- Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Cascino G, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Incidence of status epilepticus in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965–1984. Neurology 1998; 50:735–741.

- Sung CY, Chu NS. Status epilepticus in the elderly: etiology, seizure type and outcome. Acta Neurol Scand 1989; 80:51–56.

- Pro S, Vicenzini E, Randi F, Pulitano P, Mecarelli O. Idiopathic late-onset absence status epilepticus: a case report with an electroclinical 14 years follow-up. Seizure 2011; 20:655–658.

- Martin Y, Artaz MA, Bornand-Rousselot A. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:476–477.

- Fernández-Torre JL, Díaz-Castroverde AG. Non-convulsive status epilepticus in elderly individuals: report of four representative cases. Age Ageing 2004; 33:78–81.

- Chung PW, Seo DW, Kwon JC, Kim H, Na DL. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus presenting as a subacute progressive aphasia. Seizure 2002; 11:449–454.

- Sheth RD, Drazkowski JF, Sirven JI, Gidal BE, Hermann BP. Protracted ictal confusion in elderly patients. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:529–532.

- Shneker BF, Fountain NB. Assessment of acute morbidity and mortality in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Neurology 2003; 61:1066–1073.

- Kellinghaus C, Loddenkemper T, Dinner DS, Lachhwani D, Lüders HO. Seizure semiology in the elderly: a video analysis. Epilepsia 2004; 45:263–267.

- Drury I, Beydoun A. Interictal epileptiform activity in elderly patients with epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998; 106:369–373.

- McBride AE, Shih TT, Hirsch LJ. Video-EEG monitoring in the elderly: a review of 94 patients. Epilepsia 2002; 43:165–169.

- Duncan JS, Sander JW, Sisodiya SM, Walker MC. Adult epilepsy. Lancet 2006; 367:1087–1100.

- McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 2004; 56:163–184.

- Pack AM, Morrell MJ. Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5(suppl 2):S24–S29.

- Granger AS. Ginkgo biloba precipitating epileptic seizures. Age Ageing 2001; 30:523–525.

- Perucca E. Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 61:246–255.

- Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, et al; VA Cooperative Study 428 Group. New onset geriatric epilepsy: a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005; 64:1868–1673.

- Garnett WR. Optimizing antiepileptic drug therapy in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:1852–1860.

- Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Staged approach to epilepsy management. Neurology 2002; 58(suppl 5):S2–S8.

- Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010; 51:1069–1077.

- Huying F, Klimpe S, Werhahn KJ. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: a cross-sectional, regional study. Seizure 2006; 15:194–197.

- Lackner TE, Cloyd JC, Thomas LW, Leppik IE. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: effect of age, gender, and comedication on patterns of use. Epilepsia 1998; 39:1083–1087.

- Galimberti CA, Magri F, Magnani B, et al. Antiepileptic drug use and epileptic seizures in elderly nursing home residents: a survey in the province of Pavia, Northern Italy. Epilepsy Res 2006; 68:1–8.

Contrary to the popular belief that epilepsy is mainly a disease of youth, nearly 25% of new-onset seizures occur after age 65.1,2 The incidence of epilepsy in this age group is almost twice the rate in children, and in people over age 80, it is triple the rate in children.3 As our population ages, the burden of “elderly-onset” epilepsy will rise.

A seizure diagnosis carries significant implications in older people, who are already vulnerable to cognitive decline, loss of functional independence, driving restrictions, and risk of falls. Newly diagnosed epilepsy further worsens quality of life.4

The causes and clinical manifestations of seizures and epilepsy in the elderly differ from those in younger people.5 Hence, it is often difficult to make a diagnosis with certainty from a wide range of differential diagnoses. Older people are also more likely to have comorbidities, further complicating the situation.

Managing seizures in the elderly is also challenging, as age-associated physiologic changes can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs. Diagnosing and managing elderly-onset epilepsy can be challenging for a family physician, an internist, a geriatrician, or even a neurologist.

In this review, we emphasize the common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly and the assessment of the clinical clues that are essential for making an accurate diagnosis. We also review the pharmacology of antiepileptic drugs used in old age and highlight the need for psychological support for patients and caregivers.

RISING PREVALENCE IN THE ELDERLY

In US Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older, the average annual incidence rate of epilepsy in 2001 to 2005 was 10.8 per 1,000.6 A large study in Finland revealed falling incidence rates of epilepsy in childhood and middle age and rising trends in the elderly.7

In the United States, the rates are higher in African Americans (18.7 per 1,000) and lower in Asian Americans and Native Americans (5.5 and 7.7 per 1,000) than in whites (10.2 per 1,000).6 Incidence rates are slightly higher for women than for men and increase with age in both sexes and all racial groups.

Acute symptomatic seizure is also common in older patients. The incidence of acute seizures in patients over age 60 was estimated at 50 to 100 per 100,000 per year in one study.7 The rate was considerably higher in men than in women. The study also found a 3.6% risk of experiencing an acute symptomatic seizure in an 80-year lifespan, which approaches that of developing epilepsy.8 The major causes of acute symptomatic seizure were traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular disease, drug withdrawal, and central nervous system infection.

CAUSES OF NEW-ONSET EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

The most common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly include cerebrovascular disease, metabolic disturbances, dementia, traumatic brain injury, tumors, and drugs.3,9–11

Cerebrovascular disease

In older adults, acute stroke is the most common cause, accounting for up to half of cases.5,12

Seizures occur in 4.4% to 8.9% of acute cerebrovascular events.13,14 The risk varies by stroke subtype, although all stroke subtypes, including transient ischemic attack, can be associated with seizure.15 For example, although 1% to 2% of patients experienced a seizure within 15 days of a transient ischemic attack or a lacunar infarct, this risk was 16.6% after an embolic stroke.15

Beyond this increased risk of “acute seizure” in the immediate poststroke period (usually defined as 1 week), the risk of epilepsy was also 20 times higher in the first year after a stroke.14 However, seizures tend to occur within the first 48 hours after the onset of ischemic stroke. In subarachnoid hemorrhage, seizures generally occur within hours.16

In a population-based study in Rochester, NY,17 epilepsy developed in two-thirds of patients with seizure related to acute stroke. Two factors that independently predicted the development of epilepsy were early seizure occurrence and recurrence of stroke.

Interestingly, the risk of stroke was three times higher in older patients who had new-onset seizure.18 Therefore, any elderly person with new-onset seizure should be assessed for cerebrovascular risk factors and treated accordingly for stroke prevention.

Metabolic disturbances

Acute metabolic disorders are common in elderly patients because of multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy. Hypoglycemia and hyponatremia need to be particularly considered in this population.19

Other well-documented metabolic causes of acute seizure, including nonketotic hyperglycemia, hypocalcemia, and uremic or hepatic encephalopathy, can all be considerations, albeit less specific to this age group.

Dementia

Primary neurodegenerative disorders associated with cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer disease, are major risk factors for new-onset epilepsy in older patients.3,5 Seizures occur in about 10% of Alzheimer patients.20 Those who have brief periods of increased confusion may actually be experiencing unrecognized complex partial seizures.21

A case-control study discovered incidence rates of epilepsy almost 10 times higher in patients who had Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia than in nondemented patients.22 A prospective cohort study in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease established that younger age, a greater degree of cognitive impairment, and a history of antipsychotic use were independent risk factors for new-onset seizures in the elderly.23 Preexisting dementia also increases the risk of poststroke epilepsy.24

Traumatic brain injury

The most common cause of brain trauma in the elderly is falls. Subdural hematoma, which can occur in the elderly with trivial trauma or sometimes even without it, needs to be considered. The risk of posttraumatic hemorrhage is especially relevant in patients taking anticoagulants.

Traumatic brain injury has a poorer prognosis in older people than in the young,25 and it accounts for up to 20% of cases of epilepsy in the elderly.26 Although no study has specifically addressed the longitudinal risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in the elderly, a study in children and young adults revealed the risk was highest in the first year, with the increased risk persisting for more than 10 years.27

Brain tumors

Between 10% and 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly are associated with tumor, typically glioma, meningioma, and brain metastasis.28,29 Seizures are usually associated more with primary than with secondary tumors, and more with low-grade tumors than high-grade ones.30

Drug-induced

Drugs and drug withdrawal can contribute to up to 10% of acute symptomatic seizures in the geriatric population.5,8,29 The elderly are susceptible to drug-induced seizure because of a higher prevalence of polypharmacy, impaired drug clearance, and heightened sensitivity to the proconvulsant side effects of medications.1 A number of commonly used drugs have been implicated,31 including:

Antibiotics such as carbapenems and high-dose penicillin

Antihistamines such as desloratadine (Clarinex)

Pain medications such as tramadol (Ul-tram) and high-dose opiates

Neuromodulators

Antidepressants such as clomipramine (Anafranil), maprotiline (Ludiomil), amoxapine (Asendin), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).32

Seizures also follow alcohol, benzodiazepine, and barbiturate withdrawal.33

Other causes

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis is a rare cause of seizures in the elderly.34 It can present with refractory seizures, confusion, and behavioral changes with or without a known concurrent neoplastic disease.

Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome, another rare consideration, can particularly affect immunosuppressed elderly patients. This syndrome is characterized clinically by headache, confusion, seizures, vomiting, and visual disturbances with radiographic vasogenic edema.35

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The signs and symptoms of a seizure may be atypical in the elderly. Seizures more often have a picture of “epileptic amnesia,” with confusion, sleepiness, or clumsiness, rather than motor manifestations such as tonic stiffening or automatism.36,37 Postictal states are also prolonged, particularly if there is underlying brain dysfunction.38 All these features render the clinical seizure manifestations more subtle and, as such, more difficult for the uninitiated caregiver to identify.

Convulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as a single generalized seizure lasting more than 5 minutes or a series of seizures lasting longer than 30 minutes without the patient’s regaining consciousness.39 The greatest increase in the incidence of status epilepticus occurs after age 60.40 It is the first seizure in about 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly.41

Mortality rates increase with age, anoxia, and duration of status epilepticus and are over 50% in patients age 80 and older.40,42

Convulsive status epilepticus is most commonly caused by stroke.40

Absence status epilepticus can occur in elderly patients as a late complication of idiopathic generalized epilepsy related to benzodiazepine withdrawal, alcohol intoxication, or initiation of psychotropic drugs.42

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus manifests as altered mental status, psychosis, lethargy, or coma.42–44 Occasionally, it presents as a more focal cognitive disturbance with aphasia or a neglect syndrome.42,45 Electroencephalographic correlates of nonconvulsive status epilepticus include focal rhythmic discharges, often arising from frontal or temporal lobes, or generalized spike or sharp and slow-wave activity.46 Its management is challenging because of delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. The risk of death is higher in patients with severely impaired mental status or acute complications.47

Table 1 lists the typical seizure manifestations peculiar to the elderly.37,48

Differential diagnosis of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly

New-onset epilepsy in elderly patients can be confused with syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac arrhythmia, metabolic disturbances, transient global amnesia, neurodegenerative disease, rapid-eye-movement sleep behavior disorder, psychogenic disorders, and other conditions (Table 2). If there is a high clinical suspicion of seizure, the patient should undergo electroencephalography (EEG) and be referred to a neurologist or epileptologist.

KEYS TO THE DIAGNOSIS

Clinical history

A reliable history and description of the event from an eyewitness or a video recording of the event are invaluable to the diagnosis of epileptic seizure. Signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis include aura, ictal pallor, urinary incontinence, tongue-biting, and motor symptoms, as well as postictal confusion, drowsiness, and speech disturbance.

Electroencephalography

EEG is the most useful diagnostic tool in epilepsy. However, an interictal EEG reading (ie, between epileptic attacks) in an elderly patient has limited utility, showing epileptiform activity in only about one-fourth of patients.49 Nonspecific EEG abnormalities such as intermittent focal slowing are seen in many older people even without seizure.50 Also, normal findings on outpatient EEG do not rule out epilepsy, as EEG is normal in about one-third of patients with epilepsy, irrespective of age.1,49 Activation procedures such as hyperventilation and photic stimulation add little to the diagnosis in the elderly.49

On the other hand, video-EEG monitoring is an excellent tool for evaluating possible epilepsy, as it allows accurate assessment of brain electrical activity during the events in question. Moreover, studies of video-EEG recording of seizures in elderly patients demonstrated epileptiform discharges on EEG in 76% of clinical ictal events.50

Therefore, routine EEG is a useful screening tool, and inpatient video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard to characterize events of concern and distinguish between epileptic and nonepileptic or psychogenic seizures.

Other diagnostic studies

Brain imaging, preferably magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, should be done in every patient with possible epilepsy due to stroke, traumatic brain injury, or other structural brain disease.51

Electrocardiography helps exclude cardiac causes such as arrhythmia.

Blood testing. Metabolically provoked seizure can be distinguished by blood analysis for electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, calcium, magnesium, liver enzymes, and drug levels (eg, ethanol). A complete blood cell count with differential and platelets should also be done in anticipation of starting antiepileptic drug therapy.

Lumbar puncture for cell count, protein, glucose, stains, and cultures should be performed whenever meningitis or encephalitis is suspected.

A sleep study with concurrent video-EEG monitoring may be required to distinguish epileptic seizures from sleep disorders.

Neuropsychological testing may help account for the degree of cognitive impairment present.

Risk factors for stroke should be assessed in every elderly person who has new-onset seizures, because the risk of stroke is high.17

Figure 1 shows the workup for an elderly patient with suspected new-onset epilepsy.

TREATING EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

Therapeutic challenges

Age-associated changes in drug absorption, protein binding, and distribution in body compartments require adjustments in drug selection and dosage. The causes and manifestations of these changes are typically multifactorial, mainly related to altered metabolism, declining plasma albumin concentrations, and increasing competition for protein binding by concomitantly used drugs.

The differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs depend on the patient’s physical status, relevant comorbidities, and concomitant medications.52 Renal and hepatic function may decline in an elderly patient; accordingly, precaution is needed in the prescribing and dosing of antiepileptic drugs.

Adverse effects from seizure medications are twice as common in elderly patients compared with younger patients. Ataxia, tremor, visual disturbance, and sedation are the most common.1 Antiepileptic drugs are also harmful to bone; induced abnormalities in bone metabolism include hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, decreased levels of active vitamin D metabolites, and hyperparathyroidism.53

Elderly patients tend to take multiple drugs, and some drugs can lower the seizure threshold, particularly antidepressants, anti-psychotics, and antibiotics.32 The herbal remedy ginkgo biloba can also precipitate seizure in this population.54

Antiepileptic drugs such as phenobarbital, primidone (Mysoline), phenytoin (Dilantin), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) can be broad-spectrum enzyme-inducers, increasing the metabolism of many drugs, including warfarin (Coumadin), cytotoxic agents, statins, cardiac antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.55 For example, carbamazepine can alter the metabolism of several hepatically metabolized drugs and cause significant hyponatremia. This is problematic in patients already taking sodium-depleting antihypertensives. Age-related cognitive decline can worsen the situation, often leading to misdiagnosis or patient noncompliance.

Table 3 profiles the interactions of commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

The ideal pharmacotherapy

No single drug is ideal for elderly patients with new-onset epilepsy. The choice mostly depends on the type of seizure and the patient’s comorbidities. The ideal antiepileptic drug would have minimal enzyme interaction, little protein binding, linear kinetics, a long half-life, a good safety profile, and a high therapeutic index. The goal of management should be to maintain the patient’s normal lifestyle with complete control of seizures and with minimal side effects.

The only randomized controlled trial in new-onset geriatric epilepsy concluded that gabapentin (Neurontin) and lamotrigine (Lamictal) should be the initial therapy in such patients.56 Trials indicate extended-release carbamazepine or levetiracetam (Keppra) can also be tried.57

The prescribing strategy includes lower initial dose, slower titration, and a lower target dose than for younger patients. Intense monitoring of dosing and drug levels is necessary to avoid toxicity. If the first drug is not tolerated well, another should be substituted. If seizures persist despite increasing dosage, a drug with a different mechanism of action should be tried.58 A patient with drug-resistant epilepsy (failure to respond to two adequate and appropriate antiepileptic drug trials59) should be referred to an epilepsy surgical center for reevaluation and consideration of epilepsy surgery.

Patient and caregiver support is an essential component of management. New-onset epilepsy in the elderly has a significant effect on quality of life, more so if the patient is already cognitively impaired. It erodes self-confidence, survival becomes difficult, and the condition is worse for patients who live alone. Driving restrictions further limit independence and increase isolation. Hence, psychological support programs can significantly boost the self-esteem and morale of such patients and their caregivers.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATION: EPILEPSY IN THE NURSING HOME

Certain points apply to the growing proportion of elderly who reside in nursing homes:

- Several studies in the United States and in Europe60–62 suggest that this subgroup is at higher risk of polypharmacy and more likely to be treated with older antiepileptic drugs.

- Only a minority of these patients (as low as 42% in one study60) received adequate monitoring of antiepileptic drug levels.

- The clinical characteristics and epileptic etiologies of these patients are less well defined.

Together, these observations highlight a particularly vulnerable population, at risk for medication toxicity as well as for undertreatment.

OUR KNOWLEDGE IS STILL GROWING

New-onset epilepsy, although common in the elderly, is difficult to diagnose because of its atypical presentation, concomitant cognitive impairment, and nonspecific abnormalities in routine investigations. But knowledge of its common causes and differential diagnoses makes the task easier. A high suspicion warrants referral to a neurologist or epileptologist.

Challenges to the management of seizures in the elderly include deranged physiologic processes, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy. No single drug is ideal for antiepileptic therapy in the elderly; the choice of drug is usually dictated by seizure type, comorbidities, and tolerance level. The treatment regimen in the elderly is more conservative, and the target dosage is lower than for younger adults. Emotional support of patient and caregivers should be an important aspect of management.

Our knowledge about new-onset epilepsy in the elderly is still growing, and future research should explore its diagnosis, treatment strategies, and care-delivery models.

Contrary to the popular belief that epilepsy is mainly a disease of youth, nearly 25% of new-onset seizures occur after age 65.1,2 The incidence of epilepsy in this age group is almost twice the rate in children, and in people over age 80, it is triple the rate in children.3 As our population ages, the burden of “elderly-onset” epilepsy will rise.

A seizure diagnosis carries significant implications in older people, who are already vulnerable to cognitive decline, loss of functional independence, driving restrictions, and risk of falls. Newly diagnosed epilepsy further worsens quality of life.4

The causes and clinical manifestations of seizures and epilepsy in the elderly differ from those in younger people.5 Hence, it is often difficult to make a diagnosis with certainty from a wide range of differential diagnoses. Older people are also more likely to have comorbidities, further complicating the situation.

Managing seizures in the elderly is also challenging, as age-associated physiologic changes can affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs. Diagnosing and managing elderly-onset epilepsy can be challenging for a family physician, an internist, a geriatrician, or even a neurologist.

In this review, we emphasize the common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly and the assessment of the clinical clues that are essential for making an accurate diagnosis. We also review the pharmacology of antiepileptic drugs used in old age and highlight the need for psychological support for patients and caregivers.

RISING PREVALENCE IN THE ELDERLY

In US Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older, the average annual incidence rate of epilepsy in 2001 to 2005 was 10.8 per 1,000.6 A large study in Finland revealed falling incidence rates of epilepsy in childhood and middle age and rising trends in the elderly.7

In the United States, the rates are higher in African Americans (18.7 per 1,000) and lower in Asian Americans and Native Americans (5.5 and 7.7 per 1,000) than in whites (10.2 per 1,000).6 Incidence rates are slightly higher for women than for men and increase with age in both sexes and all racial groups.

Acute symptomatic seizure is also common in older patients. The incidence of acute seizures in patients over age 60 was estimated at 50 to 100 per 100,000 per year in one study.7 The rate was considerably higher in men than in women. The study also found a 3.6% risk of experiencing an acute symptomatic seizure in an 80-year lifespan, which approaches that of developing epilepsy.8 The major causes of acute symptomatic seizure were traumatic brain injury, cerebrovascular disease, drug withdrawal, and central nervous system infection.

CAUSES OF NEW-ONSET EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

The most common causes of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly include cerebrovascular disease, metabolic disturbances, dementia, traumatic brain injury, tumors, and drugs.3,9–11

Cerebrovascular disease

In older adults, acute stroke is the most common cause, accounting for up to half of cases.5,12

Seizures occur in 4.4% to 8.9% of acute cerebrovascular events.13,14 The risk varies by stroke subtype, although all stroke subtypes, including transient ischemic attack, can be associated with seizure.15 For example, although 1% to 2% of patients experienced a seizure within 15 days of a transient ischemic attack or a lacunar infarct, this risk was 16.6% after an embolic stroke.15

Beyond this increased risk of “acute seizure” in the immediate poststroke period (usually defined as 1 week), the risk of epilepsy was also 20 times higher in the first year after a stroke.14 However, seizures tend to occur within the first 48 hours after the onset of ischemic stroke. In subarachnoid hemorrhage, seizures generally occur within hours.16

In a population-based study in Rochester, NY,17 epilepsy developed in two-thirds of patients with seizure related to acute stroke. Two factors that independently predicted the development of epilepsy were early seizure occurrence and recurrence of stroke.

Interestingly, the risk of stroke was three times higher in older patients who had new-onset seizure.18 Therefore, any elderly person with new-onset seizure should be assessed for cerebrovascular risk factors and treated accordingly for stroke prevention.

Metabolic disturbances

Acute metabolic disorders are common in elderly patients because of multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy. Hypoglycemia and hyponatremia need to be particularly considered in this population.19

Other well-documented metabolic causes of acute seizure, including nonketotic hyperglycemia, hypocalcemia, and uremic or hepatic encephalopathy, can all be considerations, albeit less specific to this age group.

Dementia

Primary neurodegenerative disorders associated with cognitive impairment, such as Alzheimer disease, are major risk factors for new-onset epilepsy in older patients.3,5 Seizures occur in about 10% of Alzheimer patients.20 Those who have brief periods of increased confusion may actually be experiencing unrecognized complex partial seizures.21

A case-control study discovered incidence rates of epilepsy almost 10 times higher in patients who had Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia than in nondemented patients.22 A prospective cohort study in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease established that younger age, a greater degree of cognitive impairment, and a history of antipsychotic use were independent risk factors for new-onset seizures in the elderly.23 Preexisting dementia also increases the risk of poststroke epilepsy.24

Traumatic brain injury

The most common cause of brain trauma in the elderly is falls. Subdural hematoma, which can occur in the elderly with trivial trauma or sometimes even without it, needs to be considered. The risk of posttraumatic hemorrhage is especially relevant in patients taking anticoagulants.

Traumatic brain injury has a poorer prognosis in older people than in the young,25 and it accounts for up to 20% of cases of epilepsy in the elderly.26 Although no study has specifically addressed the longitudinal risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in the elderly, a study in children and young adults revealed the risk was highest in the first year, with the increased risk persisting for more than 10 years.27

Brain tumors

Between 10% and 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly are associated with tumor, typically glioma, meningioma, and brain metastasis.28,29 Seizures are usually associated more with primary than with secondary tumors, and more with low-grade tumors than high-grade ones.30

Drug-induced

Drugs and drug withdrawal can contribute to up to 10% of acute symptomatic seizures in the geriatric population.5,8,29 The elderly are susceptible to drug-induced seizure because of a higher prevalence of polypharmacy, impaired drug clearance, and heightened sensitivity to the proconvulsant side effects of medications.1 A number of commonly used drugs have been implicated,31 including:

Antibiotics such as carbapenems and high-dose penicillin

Antihistamines such as desloratadine (Clarinex)

Pain medications such as tramadol (Ul-tram) and high-dose opiates

Neuromodulators

Antidepressants such as clomipramine (Anafranil), maprotiline (Ludiomil), amoxapine (Asendin), and bupropion (Wellbutrin).32

Seizures also follow alcohol, benzodiazepine, and barbiturate withdrawal.33

Other causes

Paraneoplastic limbic encephalitis is a rare cause of seizures in the elderly.34 It can present with refractory seizures, confusion, and behavioral changes with or without a known concurrent neoplastic disease.

Posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy syndrome, another rare consideration, can particularly affect immunosuppressed elderly patients. This syndrome is characterized clinically by headache, confusion, seizures, vomiting, and visual disturbances with radiographic vasogenic edema.35

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

The signs and symptoms of a seizure may be atypical in the elderly. Seizures more often have a picture of “epileptic amnesia,” with confusion, sleepiness, or clumsiness, rather than motor manifestations such as tonic stiffening or automatism.36,37 Postictal states are also prolonged, particularly if there is underlying brain dysfunction.38 All these features render the clinical seizure manifestations more subtle and, as such, more difficult for the uninitiated caregiver to identify.

Convulsive and nonconvulsive status epilepticus

Status epilepticus is defined as a single generalized seizure lasting more than 5 minutes or a series of seizures lasting longer than 30 minutes without the patient’s regaining consciousness.39 The greatest increase in the incidence of status epilepticus occurs after age 60.40 It is the first seizure in about 30% of new-onset seizures in the elderly.41

Mortality rates increase with age, anoxia, and duration of status epilepticus and are over 50% in patients age 80 and older.40,42

Convulsive status epilepticus is most commonly caused by stroke.40

Absence status epilepticus can occur in elderly patients as a late complication of idiopathic generalized epilepsy related to benzodiazepine withdrawal, alcohol intoxication, or initiation of psychotropic drugs.42

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus manifests as altered mental status, psychosis, lethargy, or coma.42–44 Occasionally, it presents as a more focal cognitive disturbance with aphasia or a neglect syndrome.42,45 Electroencephalographic correlates of nonconvulsive status epilepticus include focal rhythmic discharges, often arising from frontal or temporal lobes, or generalized spike or sharp and slow-wave activity.46 Its management is challenging because of delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis. The risk of death is higher in patients with severely impaired mental status or acute complications.47

Table 1 lists the typical seizure manifestations peculiar to the elderly.37,48

Differential diagnosis of new-onset epilepsy in the elderly

New-onset epilepsy in elderly patients can be confused with syncope, transient ischemic attack, cardiac arrhythmia, metabolic disturbances, transient global amnesia, neurodegenerative disease, rapid-eye-movement sleep behavior disorder, psychogenic disorders, and other conditions (Table 2). If there is a high clinical suspicion of seizure, the patient should undergo electroencephalography (EEG) and be referred to a neurologist or epileptologist.

KEYS TO THE DIAGNOSIS

Clinical history

A reliable history and description of the event from an eyewitness or a video recording of the event are invaluable to the diagnosis of epileptic seizure. Signs and symptoms that suggest the diagnosis include aura, ictal pallor, urinary incontinence, tongue-biting, and motor symptoms, as well as postictal confusion, drowsiness, and speech disturbance.

Electroencephalography

EEG is the most useful diagnostic tool in epilepsy. However, an interictal EEG reading (ie, between epileptic attacks) in an elderly patient has limited utility, showing epileptiform activity in only about one-fourth of patients.49 Nonspecific EEG abnormalities such as intermittent focal slowing are seen in many older people even without seizure.50 Also, normal findings on outpatient EEG do not rule out epilepsy, as EEG is normal in about one-third of patients with epilepsy, irrespective of age.1,49 Activation procedures such as hyperventilation and photic stimulation add little to the diagnosis in the elderly.49

On the other hand, video-EEG monitoring is an excellent tool for evaluating possible epilepsy, as it allows accurate assessment of brain electrical activity during the events in question. Moreover, studies of video-EEG recording of seizures in elderly patients demonstrated epileptiform discharges on EEG in 76% of clinical ictal events.50

Therefore, routine EEG is a useful screening tool, and inpatient video-EEG monitoring is the gold standard to characterize events of concern and distinguish between epileptic and nonepileptic or psychogenic seizures.

Other diagnostic studies

Brain imaging, preferably magnetic resonance imaging with contrast, should be done in every patient with possible epilepsy due to stroke, traumatic brain injury, or other structural brain disease.51

Electrocardiography helps exclude cardiac causes such as arrhythmia.

Blood testing. Metabolically provoked seizure can be distinguished by blood analysis for electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, glucose, calcium, magnesium, liver enzymes, and drug levels (eg, ethanol). A complete blood cell count with differential and platelets should also be done in anticipation of starting antiepileptic drug therapy.

Lumbar puncture for cell count, protein, glucose, stains, and cultures should be performed whenever meningitis or encephalitis is suspected.

A sleep study with concurrent video-EEG monitoring may be required to distinguish epileptic seizures from sleep disorders.

Neuropsychological testing may help account for the degree of cognitive impairment present.

Risk factors for stroke should be assessed in every elderly person who has new-onset seizures, because the risk of stroke is high.17

Figure 1 shows the workup for an elderly patient with suspected new-onset epilepsy.

TREATING EPILEPSY IN THE ELDERLY

Therapeutic challenges

Age-associated changes in drug absorption, protein binding, and distribution in body compartments require adjustments in drug selection and dosage. The causes and manifestations of these changes are typically multifactorial, mainly related to altered metabolism, declining plasma albumin concentrations, and increasing competition for protein binding by concomitantly used drugs.

The differences in the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of antiepileptic drugs depend on the patient’s physical status, relevant comorbidities, and concomitant medications.52 Renal and hepatic function may decline in an elderly patient; accordingly, precaution is needed in the prescribing and dosing of antiepileptic drugs.

Adverse effects from seizure medications are twice as common in elderly patients compared with younger patients. Ataxia, tremor, visual disturbance, and sedation are the most common.1 Antiepileptic drugs are also harmful to bone; induced abnormalities in bone metabolism include hypocalcemia, hypophosphatemia, decreased levels of active vitamin D metabolites, and hyperparathyroidism.53

Elderly patients tend to take multiple drugs, and some drugs can lower the seizure threshold, particularly antidepressants, anti-psychotics, and antibiotics.32 The herbal remedy ginkgo biloba can also precipitate seizure in this population.54

Antiepileptic drugs such as phenobarbital, primidone (Mysoline), phenytoin (Dilantin), and carbamazepine (Tegretol) can be broad-spectrum enzyme-inducers, increasing the metabolism of many drugs, including warfarin (Coumadin), cytotoxic agents, statins, cardiac antiarrhythmics, antihypertensives, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants.55 For example, carbamazepine can alter the metabolism of several hepatically metabolized drugs and cause significant hyponatremia. This is problematic in patients already taking sodium-depleting antihypertensives. Age-related cognitive decline can worsen the situation, often leading to misdiagnosis or patient noncompliance.

Table 3 profiles the interactions of commonly used antiepileptic drugs.

The ideal pharmacotherapy

No single drug is ideal for elderly patients with new-onset epilepsy. The choice mostly depends on the type of seizure and the patient’s comorbidities. The ideal antiepileptic drug would have minimal enzyme interaction, little protein binding, linear kinetics, a long half-life, a good safety profile, and a high therapeutic index. The goal of management should be to maintain the patient’s normal lifestyle with complete control of seizures and with minimal side effects.

The only randomized controlled trial in new-onset geriatric epilepsy concluded that gabapentin (Neurontin) and lamotrigine (Lamictal) should be the initial therapy in such patients.56 Trials indicate extended-release carbamazepine or levetiracetam (Keppra) can also be tried.57

The prescribing strategy includes lower initial dose, slower titration, and a lower target dose than for younger patients. Intense monitoring of dosing and drug levels is necessary to avoid toxicity. If the first drug is not tolerated well, another should be substituted. If seizures persist despite increasing dosage, a drug with a different mechanism of action should be tried.58 A patient with drug-resistant epilepsy (failure to respond to two adequate and appropriate antiepileptic drug trials59) should be referred to an epilepsy surgical center for reevaluation and consideration of epilepsy surgery.

Patient and caregiver support is an essential component of management. New-onset epilepsy in the elderly has a significant effect on quality of life, more so if the patient is already cognitively impaired. It erodes self-confidence, survival becomes difficult, and the condition is worse for patients who live alone. Driving restrictions further limit independence and increase isolation. Hence, psychological support programs can significantly boost the self-esteem and morale of such patients and their caregivers.

SPECIAL CONSIDERATION: EPILEPSY IN THE NURSING HOME

Certain points apply to the growing proportion of elderly who reside in nursing homes:

- Several studies in the United States and in Europe60–62 suggest that this subgroup is at higher risk of polypharmacy and more likely to be treated with older antiepileptic drugs.

- Only a minority of these patients (as low as 42% in one study60) received adequate monitoring of antiepileptic drug levels.

- The clinical characteristics and epileptic etiologies of these patients are less well defined.

Together, these observations highlight a particularly vulnerable population, at risk for medication toxicity as well as for undertreatment.

OUR KNOWLEDGE IS STILL GROWING

New-onset epilepsy, although common in the elderly, is difficult to diagnose because of its atypical presentation, concomitant cognitive impairment, and nonspecific abnormalities in routine investigations. But knowledge of its common causes and differential diagnoses makes the task easier. A high suspicion warrants referral to a neurologist or epileptologist.

Challenges to the management of seizures in the elderly include deranged physiologic processes, multiple comorbidities, and polypharmacy. No single drug is ideal for antiepileptic therapy in the elderly; the choice of drug is usually dictated by seizure type, comorbidities, and tolerance level. The treatment regimen in the elderly is more conservative, and the target dosage is lower than for younger adults. Emotional support of patient and caregivers should be an important aspect of management.

Our knowledge about new-onset epilepsy in the elderly is still growing, and future research should explore its diagnosis, treatment strategies, and care-delivery models.

- Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology 2004; 62(suppl 2):S24–S29.

- Sander JW, Hart YM, Johnson AL, Shorvon SD. National General Practice Study of Epilepsy: newly diagnosed epileptic seizures in a general population. Lancet 1990; 336:1267–1271.

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1993; 34:453–468.

- Laccheo I, Ablah E, Heinrichs R, Sadler T, Baade L, Liow K. Assessment of quality of life among the elderly with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008; 12:257–261.

- Stephen LJ, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000; 355:1441–1446.

- Faught E, Richman J, Martin R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy among older US Medicare beneficiaries. Neurology 2012; 78:448–453.

- Sillanpää M, Lastunen S, Helenius H, Schmidt D. Regional differences and secular trends in the incidence of epilepsy in Finland: a nationwide 23-year registry study. Epilepsia 2011; 52:1857–1867.

- Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Lee JR, Rocca WA. Incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1995; 36:327–333.

- Lühdorf K, Jensen LK, Plesner AM. Etiology of seizures in the elderly. Epilepsia 1986; 27:458–463.

- Granger N, Convers P, Beauchet O, et al. First epileptic seizure in the elderly: electroclinical and etiological data in 341 patients [in French]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2002; 158:1088–1095.

- Pugh MJ, Knoefel JE, Mortensen EM, Amuan ME, Berlowitz DR, Van Cott AC. New-onset epilepsy risk factors in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57:237–242.

- Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8:1019–1030.

- Bladin CF, Alexandrov AV, Bellavance A, et al. Seizures after stroke: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:1617–1622.

- Kilpatrick CJ, Davis SM, Tress BM, Rossiter SC, Hopper JL, Vandendriesen ML. Epileptic seizures in acute stroke. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:157–160.

- Giroud M, Gras P, Fayolle H, André N, Soichot P, Dumas R. Early seizures after acute stroke: a study of 1,640 cases. Epilepsia 1994; 35:959–964.

- Asconapé JJ, Penry JK. Poststroke seizures in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 1991; 7:483–492.

- So EL, Annegers JF, Hauser WA, O’Brien PC, Whisnant JP. Population-based study of seizure disorders after cerebral infarction. Neurology 1996; 46:350–355.

- Cleary P, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Late-onset seizures as a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet 2004; 363:1184–1186.

- Loiseau P. Pathologic processes in the elderly and their association with seizures. In:Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, editors. Seizures and epilepsy in the elderly. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1997:63–86.

- Hauser WA, Morris ML, Heston LL, Anderson VE. Seizures and myoclonus in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 1986; 36:1226–1230.

- Leppik IE, Birnbaum AK. Epilepsy in the elderly. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2010; 1184:208–224.

- Imfeld P, Bodmer M, Schuerch M, Jick SS, Meier CR. Seizures in patients with Alzheimer’s disease or vascular dementia: a population-based nested case-control analysis. Epilepsia 2013; 54:700–707.

- Irizarry MC, Jin S, He F, et al. Incidence of new-onset seizures in mild to moderate Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 2012; 69:368–372.

- Cordonnier C, Hénon H, Derambure P, Pasquier F, Leys D. Influence of pre-existing dementia on the risk of post-stroke epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2005; 76:1649–1653.

- Bruns J, Hauser WA. The epidemiology of traumatic brain injury: a review. Epilepsia 2003; 44(suppl 10):2–10.

- Hiyoshi T, Yagi K. Epilepsy in the elderly. Epilepsia 2000; 41(suppl 9):31–35.

- Christensen J, Pedersen MG, Pedersen CB, Sidenius P, Olsen J, Vestergaard M. Long-term risk of epilepsy after traumatic brain injury in children and young adults: a population-based cohort study. Lancet 2009; 373:1105–1110.

- Roberts MA, Godfrey JW, Caird FI. Epileptic seizures in the elderly: I. Aetiology and type of seizure. Age Ageing 1982; 11:24–28.

- Loiseau J, Loiseau P, Duché B, Guyot M, Dartigues JF, Aublet B. A survey of epileptic disorders in southwest France: seizures in elderly patients. Ann Neurol 1990; 27:232–237.

- Lote K, Stenwig AE, Skullerud K, Hirschberg H. Prevalence and prognostic significance of epilepsy in patients with gliomas. Eur J Cancer 1998; 34:98–102.

- Franson KL, Hay DP, Neppe V, et al. Drug-induced seizures in the elderly. Causative agents and optimal management. Drugs Aging 1995; 7:38–48.

- Starr P, Klein-Schwartz W, Spiller H, Kern P, Ekleberry SE, Kunkel S. Incidence and onset of delayed seizures after overdoses of extended-release bupropion. Am J Emerg Med 2009; 27:911–915.

- Hauser WA, Ng SK, Brust JC. Alcohol, seizures, and epilepsy. Epilepsia 1988; 29(suppl 2):S66–S78.

- Petit-Pedrol M, Armangue T, Peng X, et al. Encephalitis with refractory seizures, status epilepticus, and antibodies to the GABAA receptor: a case series, characterisation of the antigen, and analysis of the effects of antibodies. Lancet Neurol 2014; 13:276–286.

- Ait S, Gilbert T, Cotton F, Bonnefoy M. Cortical blindness and posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in an older patient. BMJ Case Rep 2012;pii:bcr0920114782.

- Tinuper P, Provini F, Marini C, et al. Partial epilepsy of long duration: changing semiology with age. Epilepsia 1996; 37:162–164.

- Silveira DC, Jehi L, Chapin J, et al. Seizure semiology and aging. Epilepsy Behav 2011; 20:375–377.

- Theodore WH. The postictal state: effects of age and underlying brain dysfunction. Epilepsy Behav 2010; 19:118–120.

- Lowenstein DH, Alldredge BK. Status epilepticus. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:970–976.

- Hesdorffer DC, Logroscino G, Cascino G, Annegers JF, Hauser WA. Incidence of status epilepticus in Rochester, Minnesota, 1965–1984. Neurology 1998; 50:735–741.

- Sung CY, Chu NS. Status epilepticus in the elderly: etiology, seizure type and outcome. Acta Neurol Scand 1989; 80:51–56.

- Pro S, Vicenzini E, Randi F, Pulitano P, Mecarelli O. Idiopathic late-onset absence status epilepticus: a case report with an electroclinical 14 years follow-up. Seizure 2011; 20:655–658.

- Martin Y, Artaz MA, Bornand-Rousselot A. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:476–477.

- Fernández-Torre JL, Díaz-Castroverde AG. Non-convulsive status epilepticus in elderly individuals: report of four representative cases. Age Ageing 2004; 33:78–81.

- Chung PW, Seo DW, Kwon JC, Kim H, Na DL. Nonconvulsive status epilepticus presenting as a subacute progressive aphasia. Seizure 2002; 11:449–454.

- Sheth RD, Drazkowski JF, Sirven JI, Gidal BE, Hermann BP. Protracted ictal confusion in elderly patients. Arch Neurol 2006; 63:529–532.

- Shneker BF, Fountain NB. Assessment of acute morbidity and mortality in nonconvulsive status epilepticus. Neurology 2003; 61:1066–1073.

- Kellinghaus C, Loddenkemper T, Dinner DS, Lachhwani D, Lüders HO. Seizure semiology in the elderly: a video analysis. Epilepsia 2004; 45:263–267.

- Drury I, Beydoun A. Interictal epileptiform activity in elderly patients with epilepsy. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 1998; 106:369–373.

- McBride AE, Shih TT, Hirsch LJ. Video-EEG monitoring in the elderly: a review of 94 patients. Epilepsia 2002; 43:165–169.

- Duncan JS, Sander JW, Sisodiya SM, Walker MC. Adult epilepsy. Lancet 2006; 367:1087–1100.

- McLean AJ, Le Couteur DG. Aging biology and geriatric clinical pharmacology. Pharmacol Rev 2004; 56:163–184.

- Pack AM, Morrell MJ. Epilepsy and bone health in adults. Epilepsy Behav 2004; 5(suppl 2):S24–S29.

- Granger AS. Ginkgo biloba precipitating epileptic seizures. Age Ageing 2001; 30:523–525.

- Perucca E. Clinically relevant drug interactions with antiepileptic drugs. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2006; 61:246–255.

- Rowan AJ, Ramsay RE, Collins JF, et al; VA Cooperative Study 428 Group. New onset geriatric epilepsy: a randomized study of gabapentin, lamotrigine, and carbamazepine. Neurology 2005; 64:1868–1673.

- Garnett WR. Optimizing antiepileptic drug therapy in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother 2005; 39:1852–1860.

- Brodie MJ, Kwan P. Staged approach to epilepsy management. Neurology 2002; 58(suppl 5):S2–S8.

- Kwan P, Arzimanoglou A, Berg AT, et al. Definition of drug resistant epilepsy: consensus proposal by the ad hoc Task Force of the ILAE Commission on Therapeutic Strategies. Epilepsia 2010; 51:1069–1077.

- Huying F, Klimpe S, Werhahn KJ. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: a cross-sectional, regional study. Seizure 2006; 15:194–197.

- Lackner TE, Cloyd JC, Thomas LW, Leppik IE. Antiepileptic drug use in nursing home residents: effect of age, gender, and comedication on patterns of use. Epilepsia 1998; 39:1083–1087.

- Galimberti CA, Magri F, Magnani B, et al. Antiepileptic drug use and epileptic seizures in elderly nursing home residents: a survey in the province of Pavia, Northern Italy. Epilepsy Res 2006; 68:1–8.

- Ramsay RE, Rowan AJ, Pryor FM. Special considerations in treating the elderly patient with epilepsy. Neurology 2004; 62(suppl 2):S24–S29.

- Sander JW, Hart YM, Johnson AL, Shorvon SD. National General Practice Study of Epilepsy: newly diagnosed epileptic seizures in a general population. Lancet 1990; 336:1267–1271.

- Hauser WA, Annegers JF, Kurland LT. Incidence of epilepsy and unprovoked seizures in Rochester, Minnesota: 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1993; 34:453–468.

- Laccheo I, Ablah E, Heinrichs R, Sadler T, Baade L, Liow K. Assessment of quality of life among the elderly with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2008; 12:257–261.

- Stephen LJ, Brodie MJ. Epilepsy in elderly people. Lancet 2000; 355:1441–1446.

- Faught E, Richman J, Martin R, et al. Incidence and prevalence of epilepsy among older US Medicare beneficiaries. Neurology 2012; 78:448–453.

- Sillanpää M, Lastunen S, Helenius H, Schmidt D. Regional differences and secular trends in the incidence of epilepsy in Finland: a nationwide 23-year registry study. Epilepsia 2011; 52:1857–1867.

- Annegers JF, Hauser WA, Lee JR, Rocca WA. Incidence of acute symptomatic seizures in Rochester, Minnesota, 1935–1984. Epilepsia 1995; 36:327–333.

- Lühdorf K, Jensen LK, Plesner AM. Etiology of seizures in the elderly. Epilepsia 1986; 27:458–463.

- Granger N, Convers P, Beauchet O, et al. First epileptic seizure in the elderly: electroclinical and etiological data in 341 patients [in French]. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2002; 158:1088–1095.

- Pugh MJ, Knoefel JE, Mortensen EM, Amuan ME, Berlowitz DR, Van Cott AC. New-onset epilepsy risk factors in older veterans. J Am Geriatr Soc 2009; 57:237–242.

- Brodie MJ, Elder AT, Kwan P. Epilepsy in later life. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8:1019–1030.

- Bladin CF, Alexandrov AV, Bellavance A, et al. Seizures after stroke: a prospective multicenter study. Arch Neurol 2000; 57:1617–1622.

- Kilpatrick CJ, Davis SM, Tress BM, Rossiter SC, Hopper JL, Vandendriesen ML. Epileptic seizures in acute stroke. Arch Neurol 1990; 47:157–160.

- Giroud M, Gras P, Fayolle H, André N, Soichot P, Dumas R. Early seizures after acute stroke: a study of 1,640 cases. Epilepsia 1994; 35:959–964.

- Asconapé JJ, Penry JK. Poststroke seizures in the elderly. Clin Geriatr Med 1991; 7:483–492.

- So EL, Annegers JF, Hauser WA, O’Brien PC, Whisnant JP. Population-based study of seizure disorders after cerebral infarction. Neurology 1996; 46:350–355.

- Cleary P, Shorvon S, Tallis R. Late-onset seizures as a predictor of subsequent stroke. Lancet 2004; 363:1184–1186.