User login

Advanced endoscopy training in the United States

Introduction

Comprehensive training in endoscopic retrograde cholangioscopy (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is difficult to achieve within the curriculum of a standard 3-year Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited gastroenterology fellowship. ERCP and EUS are technically challenging, operator-dependent procedures that require specialized cognitive, technical, and integrative skills.1-4 A survey of physicians performing ERCP found that only 60% felt “very comfortable” performing the procedure after completion of a standard gastroenterology fellowship.5 Procedural volumes in ERCP and EUS tend to be low among general gastroenterology fellows; in a survey, only 9% and 4.5% of trainees in standard gastrointestinal fellowships had anticipated volumes of more than 200 ERCP and EUS procedures, respectively.6 The unique skills required to safely and effectively perform ERCP and EUS, along with the growing portfolio of therapeutic procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoluminal stent placement, deep enteroscopy, advanced closure techniques, bariatric endoscopy, therapeutic EUS, and submucosal endoscopy (including endoscopic submucosal dissection and peroral endoscopic myotomy), has led to the development of dedicated postgraduate advanced endoscopy training programs.7-9

Status of advanced endoscopy training in the United States

Advanced endoscopy fellowships are typically year-long training programs completed at tertiary care centers. Over the last 2 decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of advanced endoscopy training positions.9 In 2012, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy established a match program to standardize the application process (www.asgematch.com).10 Since its inception, there have been approximately 100 applicants per year and 60 participating programs. In the 2018 match, there were 90 advanced endoscopy applicants for 69 positions. Each year, about 20% of graduating gastroenterology fellows apply for advanced endoscopy fellowship, and applicant match rates are approximately 60%.

The goal of advanced endoscopy fellowship is to teach trainees to safely and effectively perform high-risk endoscopic procedures.1,11,12 Without ACGME oversight, no defined curricular requirements exist, and programs can be quite variable. Stronger programs offer close mentorship, conferences, comprehensive didactics, research support, and regular feedback. All programs participating in this year’s match offered training in both ERCP and EUS with most offering training in EMR, ablation, and deep enteroscopy.10 Many programs also offered training in endoluminal stenting and advanced closure techniques, such as suturing. More than half offered training in endoscopic submucosal dissection, peroral endoscopic myotomy, and bariatric endoscopy, but trainee hands-on time is usually limited, and competence is not guaranteed. A recent, large, multicenter, prospective study found that the median number of ERCPs and EUSs performed by trainees during advancing endoscopy training was 350 (range 125-500) and 300 (range 155-650), respectively.2 Median number of ERCPs performed in patients with native papilla was 51 (range 32-79). Most ERCPs were performed for biliary indications, and most EUSs were performed for pancreaticobiliary indications. The study found that most advanced endoscopy trainees have limited exposure to interventional EUS procedures, ERCPs for pancreatic indications, and ERCPs requiring advanced cannulation techniques.

Competency assessment

Advanced endoscopy fellowship programs must ensure trainees have achieved technical and cognitive competence and are safe for independent practice. Methods to assess trainee competence in advanced procedures have changed significantly over the last several years.1 Historically, endoscopic training was based on an apprenticeship model. Procedural volume and subjective assessments from trainers were used as surrogates for competence. Most current societal guidelines now recommend competency thresholds – a minimum number of supervised procedures that a trainee should complete before competency can be assessed – instead of absolute procedure volume requirements.4,13,14 The ASGE recommends that at least 200 supervised independent ERCPs, including 80 independent sphincterotomies and 60 biliary stent placements, should be performed before assessing competence.4 Similarly, 225 supervised independent EUS cases are recommended before assessing competence. Importantly, these guidelines are not validated and do not account for the inherent variability in which different trainees acquire endoscopic skills.15-18

Because of the limitations of volume-based assessments of competence, a greater emphasis has been placed on developing comprehensive, standardized competency assessments. With the ACGME’s adoption of the Next Accreditation System (NAS), a greater emphasis has been placed on competency-based medical education throughout the United States. The goal of the Next Accreditation System is to ensure that specific milestones are achieved by trainees and that trainee progress is clearly reported. Similarly, within advanced endoscopic training, it is now accepted that a minimum procedural volume is a necessary, but insufficient, marker of competence.1 Therefore, recent work has focused on defining milestones, developing assessment tools with strong validity, establishing trainee learning curves, and providing trainees with continuous feedback that allows for targeted improvement. Although the data are limited, a few studies have assessed learning curves among trainees. A prospective study of 15 trainees from the Netherlands found that trainees acquire competence in ERCP skills at variable rates; specifically, trainees achieved competence in native papilla cannulation later than other ERCP skills.18 Similarly, a recent prospective multicenter study of advanced endoscopy trainees using a standardized assessment tool and cumulative sum analysis found significant variability in the learning curves for cognitive and technical aspects of ERCP.15

The EUS and ERCP Skills Assessment Tool (TEESAT) is a competence assessment tool for EUS and ERCP with strong validity evidence.2,15,19-21 The tool assesses several individual technical and cognitive skills, in addition to a global assessment of competence, and should be used in a continuous fashion throughout fellowship training. A prospective, multicenter study using the TEESAT showed substantial variability in EUS and ERCP learning curves among trainees and demonstrated the feasibility of creating a national, centralized database that allows for continuous monitoring and reporting of individualized learning curves for EUS and ERCP among advanced endoscopy trainees.2 Such a database is an important step in evolving with the ACGME/NAS reporting requirement and would allow for fellowship program directors and trainers to identify specific trainee deficiencies in order to deliver targeted remediation.

The impact of individualized feedback on trainee learning curves and EUS and ERCP quality indicators was addressed in a recently published prospective multicenter cohort study.22 In phase 1 of the study, 24 advanced endoscopy trainees from 20 programs were assessed using the TEESAT and given quarterly feedback. By the end of training, 92% and 74% of fellows had achieved overall technical competence in EUS and ERCP, respectively. In phase 2, trainees were assessed in their first year of independent practice to determine whether participation in competency-based fellowship programs results in high-quality care in independent practice. The study found that most trainees met performance thresholds for quality indicators in EUS (94% diagnostic rate of adequate samples and 84% diagnostic yield of malignancy in pancreatic masses) and ERCP (95% overall cannulation rate). While competence could not be confirmed for all trainees after fellowship completion, most met quality indicator thresholds for EUS and ERCP during the first year of independent practice. These data provide construct validity evidence for TEESAT and the data collection and reporting system that provides periodic feedback using learning curves and ultimately affirm the effectiveness of current training programs.

Establishing minimal standards for training programs

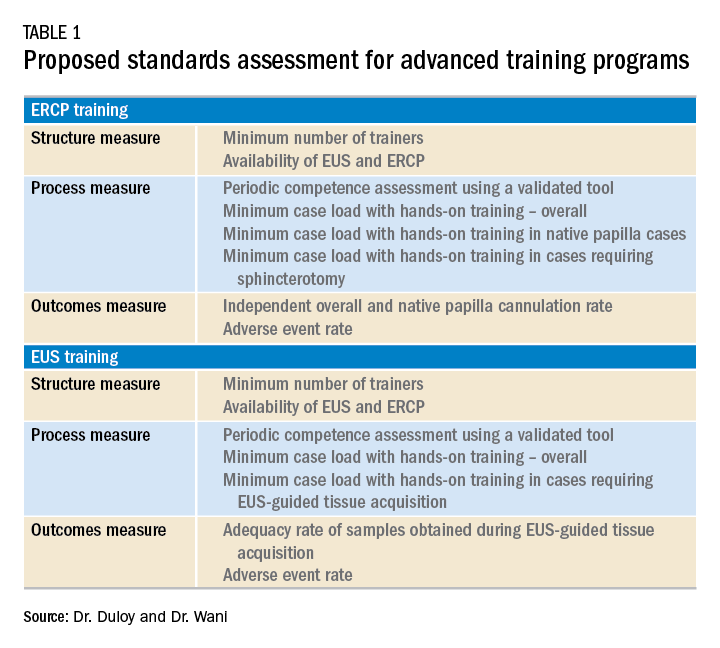

Although the ASGE offers rudimentary metrics to characterize fellowships through the match program, a more comprehensive evaluation of advanced endoscopy training programs would be of value to potential trainees. It is in this context that we offered the minimum ERCP (~250 cases for Grade 1 ERCP and ~300 cases for Grade 2 ERCP) and EUS (~225 cases) volumes that should serve as a basis for a more rigorous assessment of advanced endoscopy training programs. We also recently proposed structure, process, and outcomes measures that should be defined along with associated benchmarks (Table 1). These quality metrics could then be utilized to guide trainees in the selection of a program.

Conclusion

Advanced endoscopy training is a critical first step to ensuring endoscopists have the procedural and cognitive skills necessary to safely and effectively perform these high-risk procedures. As the portfolio of new procedures grows longer and more complex, it will become even more important for training programs to establish a standardized curriculum, adopt universal competency assessment tools, and provide continuous and targeted feedback to their trainees.

References

1. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1371-82.

2. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1758-67 e11.

3. Patel SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:956-62.

4. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:273-81.

5. Cote GA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:65-73 e12.

6. Cotton PB et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86:866-9.

7. Moffatt DC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:615-22.

8. Training and Education Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 1988;94:1083-6.

9. Elta GH et al. Gastroenterology 2015;148:488-90.

10. www.asgematch.com. (Accessed June 21, 2018)

11. Jowell PS et al. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:983-9.

12. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:780-3.

13. Polkowski M et al. Endoscopy 2012;44:190-206.

14. Committee AT et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:279-89.

15. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:711-9 e11.

16. Northup PG et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:677-80.

17. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:846-8.

18. Ekkelenkamp VE et al. Endoscopy 2014;46:949-55.

19. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1318-25 e2.

20. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:558-65.

Dr. Duloy is a therapeutic gastroenterology fellow; Dr. Wani is an associate professor of medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.

Introduction

Comprehensive training in endoscopic retrograde cholangioscopy (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is difficult to achieve within the curriculum of a standard 3-year Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited gastroenterology fellowship. ERCP and EUS are technically challenging, operator-dependent procedures that require specialized cognitive, technical, and integrative skills.1-4 A survey of physicians performing ERCP found that only 60% felt “very comfortable” performing the procedure after completion of a standard gastroenterology fellowship.5 Procedural volumes in ERCP and EUS tend to be low among general gastroenterology fellows; in a survey, only 9% and 4.5% of trainees in standard gastrointestinal fellowships had anticipated volumes of more than 200 ERCP and EUS procedures, respectively.6 The unique skills required to safely and effectively perform ERCP and EUS, along with the growing portfolio of therapeutic procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoluminal stent placement, deep enteroscopy, advanced closure techniques, bariatric endoscopy, therapeutic EUS, and submucosal endoscopy (including endoscopic submucosal dissection and peroral endoscopic myotomy), has led to the development of dedicated postgraduate advanced endoscopy training programs.7-9

Status of advanced endoscopy training in the United States

Advanced endoscopy fellowships are typically year-long training programs completed at tertiary care centers. Over the last 2 decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of advanced endoscopy training positions.9 In 2012, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy established a match program to standardize the application process (www.asgematch.com).10 Since its inception, there have been approximately 100 applicants per year and 60 participating programs. In the 2018 match, there were 90 advanced endoscopy applicants for 69 positions. Each year, about 20% of graduating gastroenterology fellows apply for advanced endoscopy fellowship, and applicant match rates are approximately 60%.

The goal of advanced endoscopy fellowship is to teach trainees to safely and effectively perform high-risk endoscopic procedures.1,11,12 Without ACGME oversight, no defined curricular requirements exist, and programs can be quite variable. Stronger programs offer close mentorship, conferences, comprehensive didactics, research support, and regular feedback. All programs participating in this year’s match offered training in both ERCP and EUS with most offering training in EMR, ablation, and deep enteroscopy.10 Many programs also offered training in endoluminal stenting and advanced closure techniques, such as suturing. More than half offered training in endoscopic submucosal dissection, peroral endoscopic myotomy, and bariatric endoscopy, but trainee hands-on time is usually limited, and competence is not guaranteed. A recent, large, multicenter, prospective study found that the median number of ERCPs and EUSs performed by trainees during advancing endoscopy training was 350 (range 125-500) and 300 (range 155-650), respectively.2 Median number of ERCPs performed in patients with native papilla was 51 (range 32-79). Most ERCPs were performed for biliary indications, and most EUSs were performed for pancreaticobiliary indications. The study found that most advanced endoscopy trainees have limited exposure to interventional EUS procedures, ERCPs for pancreatic indications, and ERCPs requiring advanced cannulation techniques.

Competency assessment

Advanced endoscopy fellowship programs must ensure trainees have achieved technical and cognitive competence and are safe for independent practice. Methods to assess trainee competence in advanced procedures have changed significantly over the last several years.1 Historically, endoscopic training was based on an apprenticeship model. Procedural volume and subjective assessments from trainers were used as surrogates for competence. Most current societal guidelines now recommend competency thresholds – a minimum number of supervised procedures that a trainee should complete before competency can be assessed – instead of absolute procedure volume requirements.4,13,14 The ASGE recommends that at least 200 supervised independent ERCPs, including 80 independent sphincterotomies and 60 biliary stent placements, should be performed before assessing competence.4 Similarly, 225 supervised independent EUS cases are recommended before assessing competence. Importantly, these guidelines are not validated and do not account for the inherent variability in which different trainees acquire endoscopic skills.15-18

Because of the limitations of volume-based assessments of competence, a greater emphasis has been placed on developing comprehensive, standardized competency assessments. With the ACGME’s adoption of the Next Accreditation System (NAS), a greater emphasis has been placed on competency-based medical education throughout the United States. The goal of the Next Accreditation System is to ensure that specific milestones are achieved by trainees and that trainee progress is clearly reported. Similarly, within advanced endoscopic training, it is now accepted that a minimum procedural volume is a necessary, but insufficient, marker of competence.1 Therefore, recent work has focused on defining milestones, developing assessment tools with strong validity, establishing trainee learning curves, and providing trainees with continuous feedback that allows for targeted improvement. Although the data are limited, a few studies have assessed learning curves among trainees. A prospective study of 15 trainees from the Netherlands found that trainees acquire competence in ERCP skills at variable rates; specifically, trainees achieved competence in native papilla cannulation later than other ERCP skills.18 Similarly, a recent prospective multicenter study of advanced endoscopy trainees using a standardized assessment tool and cumulative sum analysis found significant variability in the learning curves for cognitive and technical aspects of ERCP.15

The EUS and ERCP Skills Assessment Tool (TEESAT) is a competence assessment tool for EUS and ERCP with strong validity evidence.2,15,19-21 The tool assesses several individual technical and cognitive skills, in addition to a global assessment of competence, and should be used in a continuous fashion throughout fellowship training. A prospective, multicenter study using the TEESAT showed substantial variability in EUS and ERCP learning curves among trainees and demonstrated the feasibility of creating a national, centralized database that allows for continuous monitoring and reporting of individualized learning curves for EUS and ERCP among advanced endoscopy trainees.2 Such a database is an important step in evolving with the ACGME/NAS reporting requirement and would allow for fellowship program directors and trainers to identify specific trainee deficiencies in order to deliver targeted remediation.

The impact of individualized feedback on trainee learning curves and EUS and ERCP quality indicators was addressed in a recently published prospective multicenter cohort study.22 In phase 1 of the study, 24 advanced endoscopy trainees from 20 programs were assessed using the TEESAT and given quarterly feedback. By the end of training, 92% and 74% of fellows had achieved overall technical competence in EUS and ERCP, respectively. In phase 2, trainees were assessed in their first year of independent practice to determine whether participation in competency-based fellowship programs results in high-quality care in independent practice. The study found that most trainees met performance thresholds for quality indicators in EUS (94% diagnostic rate of adequate samples and 84% diagnostic yield of malignancy in pancreatic masses) and ERCP (95% overall cannulation rate). While competence could not be confirmed for all trainees after fellowship completion, most met quality indicator thresholds for EUS and ERCP during the first year of independent practice. These data provide construct validity evidence for TEESAT and the data collection and reporting system that provides periodic feedback using learning curves and ultimately affirm the effectiveness of current training programs.

Establishing minimal standards for training programs

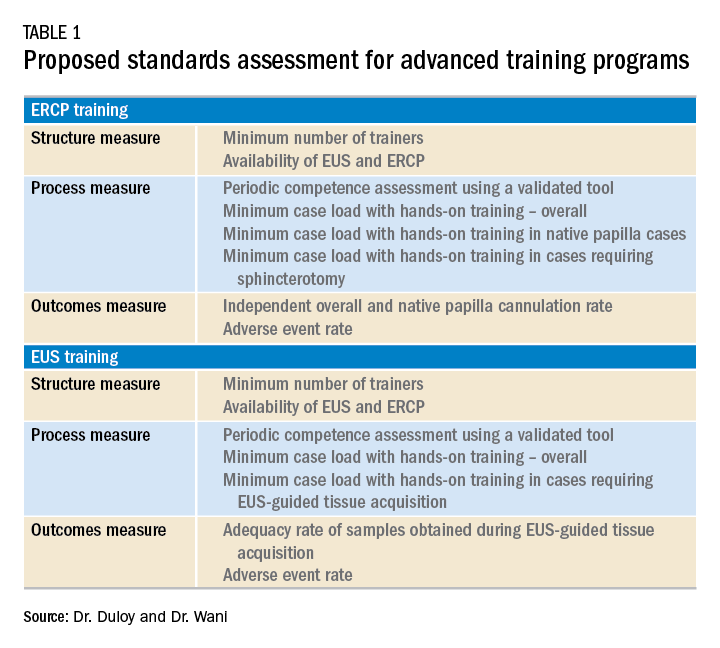

Although the ASGE offers rudimentary metrics to characterize fellowships through the match program, a more comprehensive evaluation of advanced endoscopy training programs would be of value to potential trainees. It is in this context that we offered the minimum ERCP (~250 cases for Grade 1 ERCP and ~300 cases for Grade 2 ERCP) and EUS (~225 cases) volumes that should serve as a basis for a more rigorous assessment of advanced endoscopy training programs. We also recently proposed structure, process, and outcomes measures that should be defined along with associated benchmarks (Table 1). These quality metrics could then be utilized to guide trainees in the selection of a program.

Conclusion

Advanced endoscopy training is a critical first step to ensuring endoscopists have the procedural and cognitive skills necessary to safely and effectively perform these high-risk procedures. As the portfolio of new procedures grows longer and more complex, it will become even more important for training programs to establish a standardized curriculum, adopt universal competency assessment tools, and provide continuous and targeted feedback to their trainees.

References

1. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1371-82.

2. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1758-67 e11.

3. Patel SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:956-62.

4. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:273-81.

5. Cote GA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:65-73 e12.

6. Cotton PB et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86:866-9.

7. Moffatt DC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:615-22.

8. Training and Education Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 1988;94:1083-6.

9. Elta GH et al. Gastroenterology 2015;148:488-90.

10. www.asgematch.com. (Accessed June 21, 2018)

11. Jowell PS et al. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:983-9.

12. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:780-3.

13. Polkowski M et al. Endoscopy 2012;44:190-206.

14. Committee AT et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:279-89.

15. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:711-9 e11.

16. Northup PG et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:677-80.

17. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:846-8.

18. Ekkelenkamp VE et al. Endoscopy 2014;46:949-55.

19. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1318-25 e2.

20. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:558-65.

Dr. Duloy is a therapeutic gastroenterology fellow; Dr. Wani is an associate professor of medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.

Introduction

Comprehensive training in endoscopic retrograde cholangioscopy (ERCP) and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is difficult to achieve within the curriculum of a standard 3-year Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)–accredited gastroenterology fellowship. ERCP and EUS are technically challenging, operator-dependent procedures that require specialized cognitive, technical, and integrative skills.1-4 A survey of physicians performing ERCP found that only 60% felt “very comfortable” performing the procedure after completion of a standard gastroenterology fellowship.5 Procedural volumes in ERCP and EUS tend to be low among general gastroenterology fellows; in a survey, only 9% and 4.5% of trainees in standard gastrointestinal fellowships had anticipated volumes of more than 200 ERCP and EUS procedures, respectively.6 The unique skills required to safely and effectively perform ERCP and EUS, along with the growing portfolio of therapeutic procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR), endoluminal stent placement, deep enteroscopy, advanced closure techniques, bariatric endoscopy, therapeutic EUS, and submucosal endoscopy (including endoscopic submucosal dissection and peroral endoscopic myotomy), has led to the development of dedicated postgraduate advanced endoscopy training programs.7-9

Status of advanced endoscopy training in the United States

Advanced endoscopy fellowships are typically year-long training programs completed at tertiary care centers. Over the last 2 decades, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of advanced endoscopy training positions.9 In 2012, the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy established a match program to standardize the application process (www.asgematch.com).10 Since its inception, there have been approximately 100 applicants per year and 60 participating programs. In the 2018 match, there were 90 advanced endoscopy applicants for 69 positions. Each year, about 20% of graduating gastroenterology fellows apply for advanced endoscopy fellowship, and applicant match rates are approximately 60%.

The goal of advanced endoscopy fellowship is to teach trainees to safely and effectively perform high-risk endoscopic procedures.1,11,12 Without ACGME oversight, no defined curricular requirements exist, and programs can be quite variable. Stronger programs offer close mentorship, conferences, comprehensive didactics, research support, and regular feedback. All programs participating in this year’s match offered training in both ERCP and EUS with most offering training in EMR, ablation, and deep enteroscopy.10 Many programs also offered training in endoluminal stenting and advanced closure techniques, such as suturing. More than half offered training in endoscopic submucosal dissection, peroral endoscopic myotomy, and bariatric endoscopy, but trainee hands-on time is usually limited, and competence is not guaranteed. A recent, large, multicenter, prospective study found that the median number of ERCPs and EUSs performed by trainees during advancing endoscopy training was 350 (range 125-500) and 300 (range 155-650), respectively.2 Median number of ERCPs performed in patients with native papilla was 51 (range 32-79). Most ERCPs were performed for biliary indications, and most EUSs were performed for pancreaticobiliary indications. The study found that most advanced endoscopy trainees have limited exposure to interventional EUS procedures, ERCPs for pancreatic indications, and ERCPs requiring advanced cannulation techniques.

Competency assessment

Advanced endoscopy fellowship programs must ensure trainees have achieved technical and cognitive competence and are safe for independent practice. Methods to assess trainee competence in advanced procedures have changed significantly over the last several years.1 Historically, endoscopic training was based on an apprenticeship model. Procedural volume and subjective assessments from trainers were used as surrogates for competence. Most current societal guidelines now recommend competency thresholds – a minimum number of supervised procedures that a trainee should complete before competency can be assessed – instead of absolute procedure volume requirements.4,13,14 The ASGE recommends that at least 200 supervised independent ERCPs, including 80 independent sphincterotomies and 60 biliary stent placements, should be performed before assessing competence.4 Similarly, 225 supervised independent EUS cases are recommended before assessing competence. Importantly, these guidelines are not validated and do not account for the inherent variability in which different trainees acquire endoscopic skills.15-18

Because of the limitations of volume-based assessments of competence, a greater emphasis has been placed on developing comprehensive, standardized competency assessments. With the ACGME’s adoption of the Next Accreditation System (NAS), a greater emphasis has been placed on competency-based medical education throughout the United States. The goal of the Next Accreditation System is to ensure that specific milestones are achieved by trainees and that trainee progress is clearly reported. Similarly, within advanced endoscopic training, it is now accepted that a minimum procedural volume is a necessary, but insufficient, marker of competence.1 Therefore, recent work has focused on defining milestones, developing assessment tools with strong validity, establishing trainee learning curves, and providing trainees with continuous feedback that allows for targeted improvement. Although the data are limited, a few studies have assessed learning curves among trainees. A prospective study of 15 trainees from the Netherlands found that trainees acquire competence in ERCP skills at variable rates; specifically, trainees achieved competence in native papilla cannulation later than other ERCP skills.18 Similarly, a recent prospective multicenter study of advanced endoscopy trainees using a standardized assessment tool and cumulative sum analysis found significant variability in the learning curves for cognitive and technical aspects of ERCP.15

The EUS and ERCP Skills Assessment Tool (TEESAT) is a competence assessment tool for EUS and ERCP with strong validity evidence.2,15,19-21 The tool assesses several individual technical and cognitive skills, in addition to a global assessment of competence, and should be used in a continuous fashion throughout fellowship training. A prospective, multicenter study using the TEESAT showed substantial variability in EUS and ERCP learning curves among trainees and demonstrated the feasibility of creating a national, centralized database that allows for continuous monitoring and reporting of individualized learning curves for EUS and ERCP among advanced endoscopy trainees.2 Such a database is an important step in evolving with the ACGME/NAS reporting requirement and would allow for fellowship program directors and trainers to identify specific trainee deficiencies in order to deliver targeted remediation.

The impact of individualized feedback on trainee learning curves and EUS and ERCP quality indicators was addressed in a recently published prospective multicenter cohort study.22 In phase 1 of the study, 24 advanced endoscopy trainees from 20 programs were assessed using the TEESAT and given quarterly feedback. By the end of training, 92% and 74% of fellows had achieved overall technical competence in EUS and ERCP, respectively. In phase 2, trainees were assessed in their first year of independent practice to determine whether participation in competency-based fellowship programs results in high-quality care in independent practice. The study found that most trainees met performance thresholds for quality indicators in EUS (94% diagnostic rate of adequate samples and 84% diagnostic yield of malignancy in pancreatic masses) and ERCP (95% overall cannulation rate). While competence could not be confirmed for all trainees after fellowship completion, most met quality indicator thresholds for EUS and ERCP during the first year of independent practice. These data provide construct validity evidence for TEESAT and the data collection and reporting system that provides periodic feedback using learning curves and ultimately affirm the effectiveness of current training programs.

Establishing minimal standards for training programs

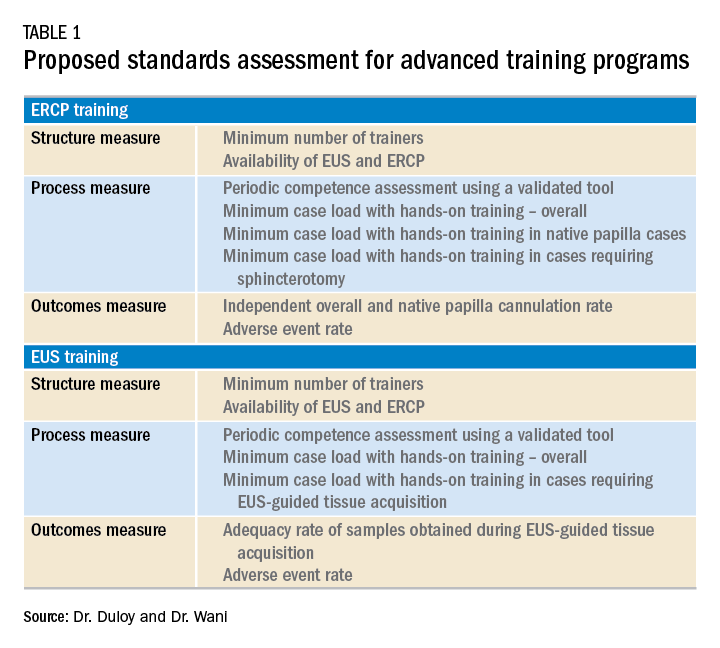

Although the ASGE offers rudimentary metrics to characterize fellowships through the match program, a more comprehensive evaluation of advanced endoscopy training programs would be of value to potential trainees. It is in this context that we offered the minimum ERCP (~250 cases for Grade 1 ERCP and ~300 cases for Grade 2 ERCP) and EUS (~225 cases) volumes that should serve as a basis for a more rigorous assessment of advanced endoscopy training programs. We also recently proposed structure, process, and outcomes measures that should be defined along with associated benchmarks (Table 1). These quality metrics could then be utilized to guide trainees in the selection of a program.

Conclusion

Advanced endoscopy training is a critical first step to ensuring endoscopists have the procedural and cognitive skills necessary to safely and effectively perform these high-risk procedures. As the portfolio of new procedures grows longer and more complex, it will become even more important for training programs to establish a standardized curriculum, adopt universal competency assessment tools, and provide continuous and targeted feedback to their trainees.

References

1. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87:1371-82.

2. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:1758-67 e11.

3. Patel SG et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:956-62.

4. Committee ASoP et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:273-81.

5. Cote GA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:65-73 e12.

6. Cotton PB et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2017;86:866-9.

7. Moffatt DC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:615-22.

8. Training and Education Committee of the American Gastroenterological Association. Gastroenterology 1988;94:1083-6.

9. Elta GH et al. Gastroenterology 2015;148:488-90.

10. www.asgematch.com. (Accessed June 21, 2018)

11. Jowell PS et al. Ann Intern Med 1996;125:983-9.

12. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2002;55:780-3.

13. Polkowski M et al. Endoscopy 2012;44:190-206.

14. Committee AT et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:279-89.

15. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2016;83:711-9 e11.

16. Northup PG et al. Gastroenterology 2013;144:677-80.

17. Eisen GM et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2001;53:846-8.

18. Ekkelenkamp VE et al. Endoscopy 2014;46:949-55.

19. Wani S et al. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1318-25 e2.

20. Wani S et al. Gastrointest Endosc 2013;77:558-65.

Dr. Duloy is a therapeutic gastroenterology fellow; Dr. Wani is an associate professor of medicine, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, Colo.