User login

A Veteran With Recurrent, Painful Knee Effusion

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

Case Presentation: A 39-year-old Air Force veteran was admitted to the US Department of Veterans Affairs Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) for evaluation of recurrent, painful right knee effusions. On presentation, his vital signs were stable, and the examination was significant for a right knee with a large effusion and tenderness to palpation without erythema or warmth. His white blood cell count was 12.0 cells/L with an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 23 mm/h and C-reactive protein of 11.87 mg/L. He was in remission from alcohol use but had relapsed on alcohol in the past day to treat the pain. He had a history of IV drug use but was in remission. He was previously active and enjoyed long hikes. Nine months prior to presentation, he developed his first large right knee effusion associated with pain. He reported no antecedent trauma. At that time, he presented to another hospital and underwent arthrocentesis with orthopedic surgery, but this did not lead to a diagnosis, and the effusion reaccumulated within 24 hours. Four months later, he received a corticosteroid injection that provided only minor, temporary relief. He received 5 additional arthrocenteses over 9 months, all without definitive diagnosis and with rapid reaccumulation of the fluid. His most recent arthrocentesis was 3 weeks before admission.

►Lauren E. Merz, MD, MSc, Chief Medical Resident, VABHS: Dr. Jindal, what is your approach and differential diagnosis for joint effusions in hospitalized patients?

►Shivani Jindal, MD, MPH, Hospitalist, VABHS, Instructor in Medicine, Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM): A thorough history and physical examination are important. I specifically ask about chronicity, pain, and trauma. A medical history of potential infectious exposures and the history of the present illness are also important, such as the risk of sexually transmitted infections, exposure to Lyme disease or other viral illnesses. Gonococcal arthritis is one of the most common causes of nontraumatic monoarthritis in young adults but can also present as a migratory polyarthritis.1

It sounds like he was quite active and liked to hike so a history of tick exposure is important to ascertain. I would also ask about eye inflammation and back pain to assess possible ankylosing spondyarthritis. Other inflammatory etiologies, such as gout are common, but it would be surprising to miss this diagnosis on repeated arthocenteses. A physical examination can confirm monoarthritis over polyarthritis and assess for signs of inflammatory arthritis (eg, warmth and erythema). The most important etiology to assess for and rule out in a person admitted to the hospital is septic arthritis. The severe pain, mild leukocytosis, and mildly elevated inflammatory markers could be consistent with this diagnosis but are nonspecific. However, the chronicity of this patient’s presentation and hemodynamic stability make septic arthritis less likely overall and a more indolent infection or other inflammatory process more likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient’s medical history included posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and antisocial personality disorder with multiple prior suicide attempts. He also had a history of opioid use disorder (OUD) with prior overdose and alcohol use disorder (AUD). Given his stated preference to avoid opioids and normal liver function and liver chemistry testing, the initial treatment was with acetaminophen. After this failed to provide satisfactory pain control, IV hydromorphone was added.

Dr. Jindal, how do you approach pain control in the hospital for musculoskeletal issues like this?

►Dr. Jindal: Typically, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) are most effective for musculoskeletal pain, often in the form of ketorolac or ibuprofen. However, we are often limited in our NSAID use by kidney disease, gastritis, or cardiovascular disease.

►Dr. Merz: On hospital day 1, the patient asked to leave to consume alcohol to ease unremitting pain. He also expressed suicidal ideation and discharge was therefore felt to be unsafe. He was reluctant to engage with psychiatry and became physically combative while attempting to leave the hospital, necessitating the use of sedating medications and physical restraints.

Dr. Shahal, what factors led to the decision to place an involuntary hold, and how do you balance patient autonomy and patient safety?

►Dr. Talya Shahal, MD, Consult-Liaison Psychiatry Service, VABHS, Instructor in Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School: This is a delicate balance that requires constant reassessment. The patient initially presented to the emergency department with suicidal ideation, stating he was not able to tolerate the pain and thus resumed alcohol consumption after a period of nonuse. He had multiple risk factors for suicide, including 9 prior suicide attempts with the latest less than a year before presentation, active substance use with alcohol and other recreational drugs, PTSD, pain, veteran status, male sex, single status, and a history of trauma.3,4 He was also displaying impulsivity and limited insight, did not engage in his psychiatric assessment, and attempted to assault staff. As such, his suicide risk was assessed to be high at the time of the evaluation, which led to the decision to place an involuntary hold. However, we reevaluate this decision at least daily in order to reassess the risk and ensure that the balance between patient safety and autonomy are maintained.

►Dr. Merz: The involuntary hold was removed within 48 hours as the patient remained calm and engaged with the primary and consulting teams. He requested escalating doses of opioids as he felt the short-acting IV medications were not providing sustained relief. However, he was also noted to be walking outside of the hospital without assistance, and he repeatedly declined nonopioid pain modalities as well as buprenorphine/naloxone. The chronic pain service was consulted but was unable to see the patient as he was frequently outside of his room.

Dr. Shahal, how do you address OUD, pain, and stigma in the hospital?

►Dr. Shahal: It is important to remember that patients with substance use disorder (SUD) and mental illness frequently have physical causes for pain and are often undertreated.5 Patients with SUD may also have higher tolerance for opioids and may need higher doses to treat the pain.5 Modalities like buprenorphine/naloxone can be effective to treat OUD and pain, but these usually cannot be initiated while the patient is on short-acting opioids as this would precipitate withdrawal.6 However, withdrawal can be managed while inpatient, and this can be a good time to start these medications as practitioners can aggressively help with symptom control. Proactively addressing mental health concerns, particularly anxiety, AUD, insomnia, PTSD, and depression, can also have a direct impact on the perception of pain and assist with better control.2 In addition, nonpharmacologic options, such as meditation, deep breathing, and even acupuncture and Reiki can be helpful and of course less harmful to treat pain.2

► Dr. Merz: An X-ray of the knee showed no acute fracture or joint space narrowing. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed a large knee effusion with no evidence of ligament injury. Synovial fluid showed turbid, yellow fluid with 14,110 nucleated cells (84% segmented cells and 4000 RBCs). Gram stain was negative, culture had no growth, and there were no crystals. Anticyclic citrullinated peptide (anti-CCP), rheumatoid factor, HIV testing, and HLA-B27 were negative.

Dr. Serrao, what do these studies tell us about the joint effusion and the possible diagnoses?

► Dr. Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease, VABHS, Clinical Associate Professor in Medicine, BUSM: I would expect the white blood cell (WBC) count to be > 50,000 cells with > 75% polymorphonuclear cells and a positive Gram stain if this was a bacterial infection resulting in septic arthritis.7 This patient’s studies are not consistent with this diagnosis nor is the chronicity of his presentation. There are 2 important bacteria that can present with inflammatory arthritis and less pronounced findings on arthrocentesis: Borrelia burgdorferi (the bacteria causing Lyme arthritis) and Neisseria gonorrhea. Lyme arthritis could be consistent with this relapsing remitting presentation as you expect a WBC count between 3000 and 100,000 cells with a mean value between 10,000 and 25,000 cells, > 50% polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and negative Gram stains.8 Gonococcal infections often do not have marked elevations in the WBC count and the Gram stain can be variable, but you still expect the WBC count to be > 30,000 cells.7 Inflammatory causes such as gout or autoimmune conditions such as lupus often have a WBC count between 2000 and 100,000 with a negative Gram stain, which could be consistent with this patient’s presentation.7 However, the lack of crystals rules out gout and the negative anti-CCP, rheumatoid factor, and HLA-B27 make rheumatologic diseases less likely.

►Dr. Merz: The patient received a phone call from another hospital where an arthrocentesis had been performed 3 weeks before. The results included a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test for Lyme disease in the synovial fluid. A subsequent serum Lyme screen was positive for 1 of 3 immunoglobulin (Ig) M bands and 10 of 10 IgG bands.

Dr. Serrao, how does Lyme arthritis typically present, and are there aspects of this case that make you suspect the diagnosis? Does the serum Lyme test give us any additional information?

►Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of Lyme disease. Patients typically have persistent or intermittent arthritis, and large joints are more commonly impacted than small joints. Monoarthritis of the knee is the most common, but oligoarthritis is possible as well. The swelling usually begins abruptly, lasts for weeks to months, and effusions typically recur quickly after aspiration. These findings are consistent with the patient’s clinical history.

For diagnostics, the IgG Western blot is positive if 5 of the 10 bands are positive.9 This patient far exceeds the IgG band number to diagnose Lyme disease. All patients with Lyme arthritis will have positive IgG serologies since Lyme arthritis is a late manifestation of the infection. IgM reactivity may be present, but are not necessary to diagnose Lyme arthritis.10 Synovial fluid is often not analyzed for antibody responses as they are susceptible to false positive results, but synovial PCR testing like this patient had detects approximately 70% of patients with untreated Lyme arthritis.11 However, PCR positivity does not necessarily equate with active infection. Serologic testing for Lyme disease by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western blot as well as careful history and the exclusion of other diagnoses are usually sufficient to make the diagnosis.

► Dr. Merz: On further history the patient reported that 5 years prior he found a tick on his skin with a bull’s-eye rash. He was treated with 28 days of doxycycline at that time. He did not recall any tick bites or rashes in the years since.

Dr. Serrao, is it surprising that he developed Lyme arthritis 5 years after exposure and after being treated appropriately? What is the typical treatment approach for a patient like this?

►Dr. Serrao: It is atypical to develop Lyme arthritis 5 years after reported treatment of what appeared to be early localized disease, namely, erythema migrans. This stage is usually cured with 10 days of treatment alone (he received 28 days) and is generally abortive of subsequent stages, including Lyme arthritis. Furthermore, the patient reported no symptoms of arthritis until recently since that time. Therefore, one can argue that the excessively long span of time from treatment to these first episodes of arthritis suggests the patient could have been reinfected. When available, comparing the types and number of Western blot bands (eg, new and/or more bands on subsequent serologic testing) can support a reinfection diagnosis. A delayed postinfectious inflammatory process from excessive proinflammatory immune responses that block wound repair resulting in proliferative synovitis is also possible.12 This is defined as the postinfectious, postantibiotic, or antibiotic-refractory Lyme arthritis, a diagnosis of exclusion more apparent only after patients receive appropriate antibiotic courses for the possibility of untreated Lyme as an active infection.12

Given the inherent diagnostic uncertainty between an active infection and posttreatment Lyme arthritis syndromes, it is best to approach most cases of Lyme arthritis as an active infection first especially if not yet treated with antibiotics. Diagnosis of postinflammatory processes should be considered if symptoms persist after appropriate antibiotics, and then short-term use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, rather than further courses of antibiotics, is recommended.

► Dr. Merz: The patient was initiated on doxycycline with the plan to transition to ceftriaxone if there was no response. One day after diagnosis and treatment initiation and in the setting of continued pain, the patient again asked to leave the hospital to drink alcohol. After eloping and becoming intoxicated with alcohol, he returned to his room. He remained concerned about his continued pain and lack of adequate pain control. At the time, he was receiving hydromorphone, ketorolac, lorazepam, gabapentin, and quetiapine.

Dr. Serrao, do you expect this degree of pain from Lyme arthritis?

► Dr. Serrao: Lyme arthritis is typically less painful than other forms of infectious or inflammatory arthritis. Pain is usually caused by the pressure from the acute accumulation and reaccumulation of fluid. In this case, the rapid accumulation of fluid that this patient experienced as well as relief with arthrocentesis suggests that the size and acuity of the effusion was causing great discomfort. Repeated arthrocentesis can prove to be a preventative strategy to minimize synovial herniation.

►Dr. Merz: Dr. Shahal, how do you balance the patient subjectively telling you that they are in pain with objective signs that they may be tolerating the pain like walking around unassisted? Is there anything else that could have been done to prevent this adverse outcome?

►Dr. Shahal: This is one of the hardest pieces of pain management. We want to practice beneficence by believing our patients and addressing their discomfort, but we also want to practice nonmaleficence by avoiding inappropriate long-term pain treatments like opioids that have significant harm as well as avoiding exacerbating this patient’s underlying SUD. An agent like buprenorphine/naloxone could have been an excellent fit to treat pain and SUD, but the patient’s lack of interest and the frequent use of short-acting opioids were major barriers. A chronic pain consult early on is helpful in cases like this as well, but they were unable to see him since he was often out of his room. Repeated arthrocentesis may also have helped the pain. Treatment of anxiety and insomnia with medications like hydroxyzine, trazodone, melatonin, gabapentin, or buspirone as well as interventions like sleep hygiene protocols or spiritual care may have helped somewhat as well.

We know that there is a vicious cycle between pain and poorly controlled mood symptoms. Many of our veterans have PTSD, anxiety, and SUD that are exacerbated by hospitalization and pain. Maintaining optimal communication between the patient and the practitioners, using trauma-informed care, understanding the patient’s goals of care, setting expectations and limits, and attempting to address the patient’s needs while attempting to minimize stigma might be helpful. However, despite optimal care, sometimes these events cannot be avoided.

►Dr. Merz: The patient was ultimately transferred to an inpatient psychiatric unit where a taper plan for the short-acting opioids was implemented. He was psychiatrically stabilized and discharged a few days later off opioids and on doxycycline. On follow-up a few weeks later, his pain had markedly improved, and the effusion was significantly reduced in size. His mood and impulsivity had stabilized. He continues to follow-up in the infectious disease clinic.

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

1. Siva C, Velazquez C, Mody A, Brasington R. Diagnosing acute monoarthritis in adults: a practical approach for the family physician. Am Fam Physician. 2003;68(1):83-90.

2. Qaseem A, McLean RM, O’Gurek D, et al. Nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic management of acute pain from non-low back, musculoskeletal injuries in adults: a clinical guideline from the American College of Physicians and American Academy of Family Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(9):739-748. doi:10.7326/M19-3602

3. Silverman MM, Berman AL. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part I: a focus on suicide ideation in assessing suicide risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):420-431. doi:10.1111/sltb.12065

4. Berman AL, Silverman MM. Suicide risk assessment and risk formulation part II: Suicide risk formulation and the determination of levels of risk. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(4):432-443. doi:10.1111/sltb.12067

5. Quinlan J, Cox F. Acute pain management in patients with drug dependence syndrome. Pain Rep. 2017;2(4):e611. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1097/PR9.0000000000000611

6. Chou R, Wagner J, Ahmed AY, et al. Treatments for Acute Pain: A Systematic Review. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK566506/

7. Seidman AJ, Limaiem F. Synovial fluid analysis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022. Updated May 8, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537114

8. Arvikar SL, Steere AC. Diagnosis and treatment of Lyme arthritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2015;29(2):269-280. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2015.02.004

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendations for test performance and interpretation from the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. JAMA. 1995;274(12):937.

10. Craft JE, Grodzicki RL, Steere AC. Antibody response in Lyme disease: evaluation of diagnostic tests. J Infect Dis. 1984;149(5):789-795. doi:10.1093/infdis/149.5.789

11. Nocton JJ, Dressler F, Rutledge BJ, Rys PN, Persing DH, Steere AC. Detection of Borrelia burgdorferi DNA by polymerase chain reaction in synovial fluid from patients with Lyme arthritis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330(4):229-234. doi:10.1056/NEJM199401273300401

12. Steere AC. Posttreatment Lyme disease syndromes: distinct pathogenesis caused by maladaptive host responses. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2148-2151. doi:10.1172/JCI138062

Boston VA Medical Forum: HIV-Positive Veteran With Progressive Visual Changes

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, chief medical resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Serrao, when you hear about vision changes in a patient with HIV, what differential diagnosis is generated? What epidemiologic or historical factors can help distinguish these entities?

►Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease Service, VABHS and assistant professor of medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. The differential diagnoses for vision changes in a patient with HIV is based on the overall immunosuppression of the patient: the lower the patient’s CD4 count, the higher the number of etiologies.1 The portions of the visual pathway as well as the pattern of vision loss are useful in narrowing the differential. For example, monocular visual disturbances with dermatomal vesicles within the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve strongly implicates varicella zoster retinitis or keratitis; abducens nerve palsy could suggest granulomatous basilar meningitis from cryptococcosis. Likewise, ongoing fevers in an advanced AIDS patient with concomitant colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis is strongly suspicious for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis with wide dissemination.

Geographic epidemiologic factors can suggest pathogens more prevalent to certain regions of the world, such as histoplasma chorioretinitis in a resident of the central and eastern U.S. or tuberculosis in a returning traveler. Likewise, a cat owner or one who consumes steak tartare increases the likelihood for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, or syphilis in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the U.S. given that the majority of new cases occur in this patient population. Other clues one should consider include the presence of splinter hemorrhages in the extremities in an intravenous drug user, raising the possibility of embolic endophthalmitis from bacterial or fungal endocarditis. A variety of other diagnoses can certainly occur as a result of drug treatment (uveitis from rifampin, for example), immune reconstitution from HAART, infections with other HIV-associated pathogens, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci, and many non-HIV-related ocular diseases.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Butler, what concerns do you have when you hear about an HIV-infected patient with vision loss from the ophthalmology perspective?

►Nicholas Butler, MD, Ophthalmology Service, Uveitis and Ocular Immunology, VABHS and assistant professor of ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School. Of course, patients with HIV suffer from common causes of vision loss—cataract, glaucoma, diabetes, macular degeneration, for instance—just like those without HIV infection. If there is no significant immunodeficiency, then the patient’s HIV status would be less relevant, and these more common causes of vision loss should be pursued. My first task would be to determine the patient’s most recent CD4 T-cell count.

Assuming an HIV-positive individual is experiencing visual symptoms related to his/her underlying HIV infection (especially in the setting of CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3), ocular opportunistic infections (OOI) come to mind first. Despite a reduction in incidence of 75% to 80% in the HAART-era, CMV retinitis remains the most common OOI in patients with AIDS and carries the greatest risk of ocular morbidity.2 In fact, based on enrollment data for the Longitudinal Study of the Ocular Complications of AIDS (LSOCA), the prevalence of CMV retinitis among patients with AIDS is more than 20-fold higher than all other ocular complications of AIDS (OOIs and ocular neoplastic disease), including Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, ocular syphilis, ocular toxoplasma, necrotizing herpetic retinitis, cryptococcal choroiditis, and pneumocystis choroiditis.3 Beyond ocular opportunistic infections, the most common retinal finding in HIV-positive people is HIV retinopathy, nonspecific microvascular findings in the retina affecting nearly 70% of those with advanced HIV disease. Fortunately, HIV retinopathy is generally asymptomatic.4

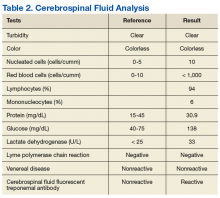

►Dr. Swamy. Thank you for those explanations. Based on Dr. Serrao’s differential, it is worth noting that this patient is MSM. He was evaluated in urgent care with the initial examination showing a temperature of 98.0° F, pulse 83 beats per minute, and blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg. The eye exam showed no injection with normal extraocular movements. Initial laboratory data were notable for a CD4 count of 730 cells/mm3 with fewer than 20 HIV viral copies/mL. Cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G (IgG) was positive, and immunoglobulin M (IgM) was negative. A Lyme antibody was positive with negative IgM and IgG by Western blot. Additional tests can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. The patient has good immunologic and virologic control. How does this change your thinking about the case?

►Dr. Serrao. His CD4 count is well above 350, increasing the likelihood of a relatively uncomplicated course and treatment. Cytomegalovirus antibodies reflect prior infection. As CMV generally does not manifest with disease of any variety (including CMV retinitis) at this high CD4 count, one can presume he does not have CMV retinitis as a cause for his visual changes. CMV retinitis occurs mainly when substantial CD4 depletion has occurred (typically less than 50 cells/mm3). A positive Lyme antibody screen, not specific to Lyme, can be falsely positive in other treponema diseases (eg, Treponema pallidum, the etiologic organism of syphilis) as evidenced by negative confirmatory Western blot IgG and IgM. Antineutrophil cystoplasmic antibodies, lysozyme, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), herpes simplex virus, toxoplasma are generally included in the workup for the differential of uveitis, retinitis, choroiditis, etc.

►Dr. Swamy. Based on the visual changes, the patient was referred for urgent ophthalmologic evaluation. Dr. Butler, when should a generalist consider urgent ophthalmology referral?

►Dr. Butler. In general, all patients with acute (and significant) vision loss should be referred immediately to an ophthalmologist. The challenge for the general practitioner is determining the true extent of the reported vision loss. If possible, some assessment of visual acuity should be obtained, testing each eye independently and with the correct glasses correction (ie, the patient’s distance glasses if the test object is 12 feet or more from the patient or their reading glasses if the test object is held inside arm’s length). If the general practitioner does not have access to an eye chart or near card, any assessment of vision with an appropriate description will be useful (eg, the patient can quickly count fingers at 15 feet in the unaffected eye, but the eye with reported vision loss cannot reliably count fingers outside of 2 feet). Additional ocular symptoms associated with the vision loss, such as pain, redness, photophobia, new flashes or floaters, increase the urgency of the referral. The threshold for referral for any ocular complaint is lower compared with that of the general population for those with evidence of immunodeficiency, such as for this patient with HIV. Any CD4 count < 200 cells/mm3 should raise the practitioner’s concern for an ocular opportunistic infection, with the greatest concern with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3.

►Dr. Swamy. The patient underwent further testing in the ophthalmology clinic. Dr. Butler, can you please interpret the funduscopic exam?

►Dr. Butler. Both eyes demonstrate findings (microaneurysms and small dot-blot hemorrhages) consistent with moderate nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (Figure 1A, white arrows). HIV-associated retinopathy could produce similar findings, but it is not generally seen with CD4 counts > 200 cells/mm3. Additionally, in the left eye, there is a diffuse patch of retinal whitening (retinitis) associated with the inferotemporal vascular arcades (Figure 1B, white arrows). The entire area involved is poorly circumscribed and the whitening is subtle in areas. Overlying some areas of deeper, ground-glass whitening there are scattered, punctate white spots (Figure 1B, green arrows). Wickremasinghe and colleagues described this pattern of retinitis and suggested that it had a high positive-predictive value in the diagnosis of ocular syphilis.5

►Dr. Swamy. The patient then underwent fluorescein angiography and optical coherence tomography (OCT). Dr. Butler, what did the fluorescein angiography show?

►Dr. Butler. The fluorescein angiogram in both eyes revealed leakage of dye consistent with diabetic retinopathy, with the right eye (OD) worse than the left (OS). Additionally, the areas of active retinitis in the left eye displayed gradual staining with leopard-spot changes, along with late leakage of fluorescein dye, indicating vasculopathy in the infected area (Figure 2, arrows). The patient also underwent OCT in the left eye (images not displayed) demonstrating vitreous cells (vitritis), patches of inner retinal thickening with hyperreflectivity, and hyperreflective nodules at the level of the retinal pigment epithelium with overlying photoreceptor disruption. These OCT findings are fairly stereotypic for syphilitic chorioretinitis.6

►Dr. Swamy. Based on the ophthalmic findings, a diagnosis of ocular syphilis was made. Dr. Serrao, what should internists consider as they evaluate and manage a patient with ocular syphilis?

►Dr. Serrao. Although isolated ocular involvement from syphilis is possible, the majority of patients (up to 85%) with HIV can present with concomitant central nervous system infection and about 30% present with symptomatic neurosyphilis (a typical late manifestation of this disease) that reflects the aggressiveness, accelerated course and propensity for wide dissemination of syphilis in this patient population.7

The presence of concomitant cutaneous rashes should prompt universal precautions, because transmission can occur via skin to skin contact. Clinicians should watch for the Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction during treatment, a syndrome of fever, myalgias, and headache, which results from circulating cytokines produced because of rapidly dying spirochetes that could mimic a penicillin drug reaction, yet is treated supportively.

As syphilis is sexually acquired, clinicians should test for coexistent sexually transmitted infections, vaccinate for those that are preventable (eg, hepatitis B), notify sexual partners via assistance from local departments of public health, and assess for coexistent drug use and offer counseling in order to optimize risk reduction. Special attention should be paid to virologic control of HIV since some studies have shown an increase in the propensity for breakthrough HIV viremia while on effective ART.9 This should warrant counseling for ongoing optimal ART adherence and close monitoring in the follow-up visits with a provider specialized in the treatment of syphilis and HIV.

►Dr. Swamy. A lumbar puncture is performed with the results listed in Table 2. Dr. Serrao, is the CSF consistent with neurosyphilis? What would you do next?

►Dr. Serrao. The lumbar puncture is inflammatory with a lymphocytic predominance, consistent with active ocular/neurosyphilis. The CSF Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test is specific but not sensitive so a negative value does not rule out the presence of central nervous system infection.10 The CSF fluorescent treponemal antibody (CSF FTA-ABS) is sensitive but not specific. In this case, the ocular findings, positive serum RPR, CSF lymphocytic predominance, and CSF FTA ABS strongly supports the diagnosis of ocular/early neurosyphilis in a patient with HIV infection in whom early aggressive treatment is warranted to prevent rapid progression/potential loss of vision.11

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Butler, how does syphilis behave in the eye as compared to other infectious or inflammatory diseases? Do visual symptoms respond well to treatment?

►Dr. Butler. As opposed to the dramatic reduction in rates and severity of CMV retinitis, HAART has had a negligible effect on ocular syphilis in the setting of HIV coinfection; in fact, rates of syphilis, including ocular syphilis, are currently surging world-wide, and HIV coinfection portends a worse prognosis.12 This is especially true among gay men. More so, there appears to be no correlation between CD4 count and incidence of developing ocular syphilis, as opposed to CMV retinitis, which occurs far more frequently in those with CD4 counts < 50 cells/mm3. In keeping with its epithet as one of the “Great Imitators,” syphilis can affect virtually every tissue of the eye—conjunctiva, sclera, cornea, iris, lens, vitreous, retina, choroid, optic nerve—unlike other OOI, such as CMV or toxoplasma, which generally hone to the retina. Nonetheless, various findings and patterns on clinical exam and ancillary testing, such as the more recently described punctate inner retinitis (as seen in our patient) and the more classic acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis, carry high specificity for ocular syphilis.13

Patients with ocular syphilis should be treated according to neurosyphilis treatment protocols. In general, these patients respond very well to treatment with resolution of the ocular findings and recovery of complete, or nearly so, visual function, as long as an excessive delay between diagnosis and proper treatment does not occur.14

►Dr. Swamy. Following this testing, the patient completed 14 days of IV penicillin with resolution of symptoms. He had no further vision complaints. He was started on Triumeq (abacavir, dolutegravir, and lamivudine) with good adherence to therapy. Dr. Serrao, in 2016 the CDC released a clinical advisory about ocular syphilis. Can you tell us about why this is an important diagnosis to be aware of today?

►Dr. Serrao. As with any disease, the epidemiologic characteristics of an infection like syphilis allow the clinician to more carefully entertain such a diagnosis in any one individual by improving the index of suspicion for a particular disease. Awareness of an increase in ocular syphilis in HIV positive MSM allows for a more timely assessment and subsequent treatment with the goal of preventing loss of vision.15

1. Cunningham ET Jr, Margolis TP. Ocular manifestations of HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;339(4):236-244.

2. Holtzer CD, Jacobson MA, Hadley WK, et al. Decline in the rate of specific opportunistic infections at San Francisco General Hospital, 1994-1997. AIDS. 1998;12(14):1931-1933.

3. Gangaputra S, Drye L, Vaidya V, Thorne JE, Jabs DA, Lyon AT. Non-cytomegalovirus ocular opportunistic infections in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2013;155(2):206-212.e205.

4. Jabs DA, Van Natta ML, Holbrook JT, et al. Longitudinal study of the ocular complications of AIDS: 1. Ocular diagnoses at enrollment. Ophthalmology. 2007;114(4):780-786.

5. Wickremasinghe S, Ling C, Stawell R, Yeoh J, Hall A, Zamir E. Syphilitic punctate inner retinitis in immunocompetent gay men. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(6):1195-1200.

6. Burkholder BM, Leung TG, Ostheimer TA, Butler NJ, Thorne JE, Dunn JP. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography findings in acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. J Ophthalmic Inflamm Infect. 2014;4(1):2.

7. Musher DM, Hamill RJ, Baughn RE. Effect of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection on the course of syphilis and on the response to treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(11):872-881.

8. Lukehart SA, Hook EW 3rd, Baker-Zander SA, Collier AC, Critchlow CW, Handsfield HH. Invasion of the central nervous system by Treponema pallidum: implications for diagnosis and treatment. Ann Intern Med. 1988;109(11):855-862.

9. Golden MR, Marra CM, Holmes KK. Update on syphilis: resurgence of an old problem. JAMA. 2003;290(11):1510-1514.

10. Marra CM, Tantalo LC, Maxwell CL, Ho EL, Sahi SK, Jones T. The rapid plasma reagin test cannot replace the venereal disease research laboratory test for neurosyphilis diagnosis. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(6):453-457.

11. Harding AS, Ghanem KG. The performance of cerebrospinal fluid treponemal-specific antibody tests in neurosyphilis: a systematic review. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39(4):291-297.

12. Butler NJ, Thorne JE. Current status of HIV infection and ocular disease. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23(6):517-522.

13. Gass JD, Braunstein RA, Chenoweth RG. Acute syphilitic posterior placoid chorioretinitis. Ophthalmology. 1990;97(10):1288-1297.

14. Davis JL. Ocular syphilis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2014;25(6):513-518.

15. Clinical Advisory: Ocular Syphilis in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/std/syphilis/clinicaladvisoryos2015.htm. Accessed September 11, 2017.

►Lakshmana Swamy, MD, chief medical resident, VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS) and Boston Medical Center. Dr. Serrao, when you hear about vision changes in a patient with HIV, what differential diagnosis is generated? What epidemiologic or historical factors can help distinguish these entities?

►Richard Serrao, MD, Infectious Disease Service, VABHS and assistant professor of medicine, Boston University School of Medicine. The differential diagnoses for vision changes in a patient with HIV is based on the overall immunosuppression of the patient: the lower the patient’s CD4 count, the higher the number of etiologies.1 The portions of the visual pathway as well as the pattern of vision loss are useful in narrowing the differential. For example, monocular visual disturbances with dermatomal vesicles within the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve strongly implicates varicella zoster retinitis or keratitis; abducens nerve palsy could suggest granulomatous basilar meningitis from cryptococcosis. Likewise, ongoing fevers in an advanced AIDS patient with concomitant colitis, hepatitis, and pneumonitis is strongly suspicious for cytomegalovirus (CMV) retinitis with wide dissemination.

Geographic epidemiologic factors can suggest pathogens more prevalent to certain regions of the world, such as histoplasma chorioretinitis in a resident of the central and eastern U.S. or tuberculosis in a returning traveler. Likewise, a cat owner or one who consumes steak tartare increases the likelihood for toxoplasma retinochoroiditis, or syphilis in men who have sex with men (MSM) in the U.S. given that the majority of new cases occur in this patient population. Other clues one should consider include the presence of splinter hemorrhages in the extremities in an intravenous drug user, raising the possibility of embolic endophthalmitis from bacterial or fungal endocarditis. A variety of other diagnoses can certainly occur as a result of drug treatment (uveitis from rifampin, for example), immune reconstitution from HAART, infections with other HIV-associated pathogens, such as Pneumocystis jiroveci, and many non-HIV-related ocular diseases.

►Dr. Swamy. Dr. Butler, what concerns do you have when you hear about an HIV-infected patient with vision loss from the ophthalmology perspective?

►Nicholas Butler, MD, Ophthalmology Service, Uveitis and Ocular Immunology, VABHS and assistant professor of ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School. Of course, patients with HIV suffer from common causes of vision loss—cataract, glaucoma, diabetes, macular degeneration, for instance—just like those without HIV infection. If there is no significant immunodeficiency, then the patient’s HIV status would be less relevant, and these more common causes of vision loss should be pursued. My first task would be to determine the patient’s most recent CD4 T-cell count.

Assuming an HIV-positive individual is experiencing visual symptoms related to his/her underlying HIV infection (especially in the setting of CD4 counts < 200 cells/mm3), ocular opportunistic infections (OOI) come to mind first. Despite a reduction in incidence of 75% to 80% in the HAART-era, CMV retinitis remains the most common OOI in patients with AIDS and carries the greatest risk of ocular morbidity.2 In fact, based on enrollment data for the Longitudinal Study of the Ocular Complications of AIDS (LSOCA), the prevalence of CMV retinitis among patients with AIDS is more than 20-fold higher than all other ocular complications of AIDS (OOIs and ocular neoplastic disease), including Kaposi sarcoma, lymphoma, herpes zoster ophthalmicus, ocular syphilis, ocular toxoplasma, necrotizing herpetic retinitis, cryptococcal choroiditis, and pneumocystis choroiditis.3 Beyond ocular opportunistic infections, the most common retinal finding in HIV-positive people is HIV retinopathy, nonspecific microvascular findings in the retina affecting nearly 70% of those with advanced HIV disease. Fortunately, HIV retinopathy is generally asymptomatic.4

►Dr. Swamy. Thank you for those explanations. Based on Dr. Serrao’s differential, it is worth noting that this patient is MSM. He was evaluated in urgent care with the initial examination showing a temperature of 98.0° F, pulse 83 beats per minute, and blood pressure 110/70 mm Hg. The eye exam showed no injection with normal extraocular movements. Initial laboratory data were notable for a CD4 count of 730 cells/mm3 with fewer than 20 HIV viral copies/mL. Cytomegalovirus immunoglobulin G (IgG) was positive, and immunoglobulin M (IgM) was negative. A Lyme antibody was positive with negative IgM and IgG by Western blot. Additional tests can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. The patient has good immunologic and virologic control. How does this change your thinking about the case?

►Dr. Serrao. His CD4 count is well above 350, increasing the likelihood of a relatively uncomplicated course and treatment. Cytomegalovirus antibodies reflect prior infection. As CMV generally does not manifest with disease of any variety (including CMV retinitis) at this high CD4 count, one can presume he does not have CMV retinitis as a cause for his visual changes. CMV retinitis occurs mainly when substantial CD4 depletion has occurred (typically less than 50 cells/mm3). A positive Lyme antibody screen, not specific to Lyme, can be falsely positive in other treponema diseases (eg, Treponema pallidum, the etiologic organism of syphilis) as evidenced by negative confirmatory Western blot IgG and IgM. Antineutrophil cystoplasmic antibodies, lysozyme, angiotensin-converting enzyme, rapid plasma reagin (RPR), herpes simplex virus, toxoplasma are generally included in the workup for the differential of uveitis, retinitis, choroiditis, etc.

►Dr. Swamy. Based on the visual changes, the patient was referred for urgent ophthalmologic evaluation. Dr. Butler, when should a generalist consider urgent ophthalmology referral?