User login

Time to Stop Glucosamine and Chondroitin for Knee OA?

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member. Should you tell the patient to continue taking the medication?

Knee OA is a common condition in the United States, affecting an estimated 12% of adults ages 60 and older and 16% of those ages 70 and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that firstline treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical NSAIDs; the latter are also used if pain is unresponsive to acetaminophen.3,4 If initial therapy is inadequate to control pain, tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate are alternatives.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses ≥ 800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk for bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N > 200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8 There was no statistically significant difference in adverse events for glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, based on data from three studies included in the review.8

This RCT from Roman-Blas et al evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid), maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.1

Continue to: STUDY SUMMARY

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine not better than placebo

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in nine rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate (1,200 mg) plus glucosamine sulfate (1,500 mg) (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate-to-severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Knee pain severity was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40 to 80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics; average age in the CS/GS group was 67 and in the placebo group, 65. Exclusion criteria included BMI ≥ 35, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary endpoint was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at six months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P < .03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at six months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (–20 mm vs –12 mm; P = .029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P = .01).

Continue to: In the CS/GS group...

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the six-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P = .018).1

WHAT’S NEW

Pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone, or different dosing, would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2018. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2018; 67[9]:566-568).

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

Time to stop glucosamine and chondroitin for knee OA?

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member.

Should you tell the patient it’s okay to continue the medication?

Knee OA in the United States is a common condition and affects an estimated 12% of adults 60 years and older and 16% of adults 70 years and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that first-line treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (either initially or if unresponsive to acetaminophen).3,4 Alternative medication options for patients with an inadequate response to initial therapy include tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence of OA.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional recommendation).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses of ≥800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk of bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

[polldaddy:10097537]

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N>200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8

Continue to: Three studies included...

Three studies included in the 2015 systematic review provided data on adverse events when comparing glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, and found no statistically significant difference.8

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Roman-Blas et al1 evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid, Spain) maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine was not better than placebo for pain

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 9 rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate 1200 mg plus glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate to severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Level of knee pain was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40-80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics, and the average age in the CS/GS group was 67 years vs 65 years in the placebo group. Exclusion criteria included body mass index of ≥35 kg/m2, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary end point was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Continue to: Baseline global pain scores were...

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P<.03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at 6 months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (-20 mm vs -12 mm; P=.029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P=.01).

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the 6-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P=.018).1

WHAT’S NEW

A pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings to CS or GS alone, or different dosages

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone or different dosing would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

An all-too-common product presents challenges

CS/GC is available over the counter and advertised directly to consumers. With this medication so readily available, identifying patients who are taking the supplement and encouraging discontinuation can be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member.

Should you tell the patient it’s okay to continue the medication?

Knee OA in the United States is a common condition and affects an estimated 12% of adults 60 years and older and 16% of adults 70 years and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that first-line treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (either initially or if unresponsive to acetaminophen).3,4 Alternative medication options for patients with an inadequate response to initial therapy include tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence of OA.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional recommendation).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses of ≥800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk of bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

[polldaddy:10097537]

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N>200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8

Continue to: Three studies included...

Three studies included in the 2015 systematic review provided data on adverse events when comparing glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, and found no statistically significant difference.8

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Roman-Blas et al1 evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid, Spain) maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine was not better than placebo for pain

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 9 rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate 1200 mg plus glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate to severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Level of knee pain was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40-80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics, and the average age in the CS/GS group was 67 years vs 65 years in the placebo group. Exclusion criteria included body mass index of ≥35 kg/m2, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary end point was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Continue to: Baseline global pain scores were...

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P<.03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at 6 months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (-20 mm vs -12 mm; P=.029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P=.01).

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the 6-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P=.018).1

WHAT’S NEW

A pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings to CS or GS alone, or different dosages

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone or different dosing would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

An all-too-common product presents challenges

CS/GC is available over the counter and advertised directly to consumers. With this medication so readily available, identifying patients who are taking the supplement and encouraging discontinuation can be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

A 65-year-old man with moderately severe osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee presents to your office for his annual exam. During the medication review, the patient mentions he is using glucosamine and chondroitin for his knee pain, which was recommended by a family member.

Should you tell the patient it’s okay to continue the medication?

Knee OA in the United States is a common condition and affects an estimated 12% of adults 60 years and older and 16% of adults 70 years and older.2 The primary goals of OA therapy are to minimize pain and improve function. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) agree that first-line treatment recommendations include aerobic exercise, resistance training, and weight loss.

Initial pharmacologic therapies include full-strength acetaminophen or oral/topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (either initially or if unresponsive to acetaminophen).3,4 Alternative medication options for patients with an inadequate response to initial therapy include tramadol, other opioids, duloxetine, or intra-articular injections with corticosteroids or hyaluronate.3,4 Total knee replacement may be indicated in moderate or severe knee OA with radiographic evidence of OA.5 Vitamin D, lateral wedge insoles, and antioxidants are not currently recommended.6

Prior studies evaluating glucosamine and/or chondroitin have provided conflicting results regarding evidence on pain reduction, function, and quality of life. Therefore, guidelines on OA management do not recommend their use (AAOS, strong; ACR, conditional recommendation).3,4 However, consumption remains high, with 6.5 million US adults reporting use of glucosamine and/or chondroitin in the prior 30 days.7

A 2015 systematic review of 43 randomized trials evaluating oral chondroitin sulfate for OA of varying severity suggested there may be a significant decrease in short-term and long-term pain with doses of ≥800 mg/d compared with placebo (level of evidence, low; risk of bias, high).8 However, no significant difference was noted in short- or long-term function, and the trials were highly heterogeneous.

[polldaddy:10097537]

Studies included in the 2015 systematic review found that glucosamine plus chondroitin did not have a significant effect on short- or long-term pain or physical function compared with placebo. Although glucosamine plus chondroitin led to significantly decreased pain compared with other medication, sensitivity analyses conducted for larger studies (N>200) with adequate methods of blinding and allocation concealment found no difference in pain.8

Continue to: Three studies included...

Three studies included in the 2015 systematic review provided data on adverse events when comparing glucosamine plus chondroitin vs placebo, and found no statistically significant difference.8

This randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Roman-Blas et al1 evaluated chondroitin and glucosamine vs placebo in patients with more severe OA. The study was supported by Tedec-Meiji Farma (Madrid, Spain) maker of the combination of chondroitin plus glucosamine used in the study.

STUDY SUMMARY

Chondroitin + glucosamine was not better than placebo for pain

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 9 rheumatology referral centers and one orthopedic center in Spain. The trial evaluated the efficacy of chondroitin sulfate 1200 mg plus glucosamine sulfate 1500 mg (CS/GS) compared with placebo in 164 patients with Grade 2 or 3 knee OA and moderate to severe knee pain. OA grade was ascertained using the Kellgren-Lawrence scale, corresponding to osteophytes and either possible (Grade 2) or definite (Grade 3) joint space narrowing. Level of knee pain was defined by a self-reported global pain score of 40-80 mm on a 100-mm visual analog scale (VAS).

No significant difference was noted in group characteristics, and the average age in the CS/GS group was 67 years vs 65 years in the placebo group. Exclusion criteria included body mass index of ≥35 kg/m2, concurrent arthritic conditions, and any coexisting chronic disease that would prevent successful completion of the trial.1

The primary end point was mean reduction in global pain score on a 0- to 100-mm VAS at 6 months. Secondary outcomes included mean reduction in total and subscale scores in pain and function on the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis (WOMAC) index (0–100-mm VAS for each) and the use of rescue medication.

Continue to: Baseline global pain scores were...

Baseline global pain scores were 62 mm in both groups. Acetaminophen, up to 3 g/d, was the only allowed rescue medication. Clinic visits occurred at 4, 12, and 24 weeks. A statistically significant difference between groups was defined as P<.03.1

Results. In the intention-to-treat analysis at 6 months, patients in the placebo group had a greater reduction in pain than the CS/GC group (-20 mm vs -12 mm; P=.029). No other difference was noted between the placebo and CS/GS groups in the total or subscales of the WOMAC index, and no difference was noted in use of acetaminophen. More patients in the placebo group had at least a 50% improvement in pain or function compared with the CS/GS group (47.4% vs 27.5%; P=.01).

In the CS/GS group, 31% did not complete the 6-month treatment period, compared with 18% in the placebo group. More patients dropped out because of adverse effects (diarrhea, upper abdominal pain, and constipation) in the CS/GS group than the placebo group (33 vs 19; P=.018).1

WHAT’S NEW

A pharma-sponsored study finds treatment ineffective

The effectiveness of CS/GS for the treatment of knee OA has been in question for years, but this RCT is the first trial sponsored by a pharmaceutical company to evaluate CS/GS efficacy. This trial found evidence of a lack of efficacy. In patients with more severe OA of the knee, placebo was more effective than CS/GS, and CS/GS had significantly more adverse events. Therefore, it may be time to advise patients to stop taking their CS/GS supplement.

CAVEATS

Cannot generalize findings to CS or GS alone, or different dosages

The study compared only one medication dosing regimen using a combination of CS and GS. Whether either agent alone or different dosing would lead to the same outcome is unknown.

Continue to: CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

An all-too-common product presents challenges

CS/GC is available over the counter and advertised directly to consumers. With this medication so readily available, identifying patients who are taking the supplement and encouraging discontinuation can be a challenge.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

1. Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

2. Dillon CF, Rasch EK, Gu Q, et al. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis in the United States: arthritis data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1991-94. J Rheumatol. 2006;33:2271-2279.

3. Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64:465-474.

4. Brown GA. AAOS clinical practice guideline: treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: evidence-based guideline, 2nd ed. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21:577-579.

5. Jordan KM, Arden NK, Doherty M, et al. EULAR Recommendations 2003: an evidence based approach to the management of knee osteoarthritis: report of a Task Force of the Standing Committee for International Clinical Studies Including Therapeutic Trials (ESCISIT). Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1145-1155.

6. Ebell MH. Osteoarthritis: rapid evidence review. Am Fam Physician. 2018;97:523-526.

7. Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ, et al. Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002-2012. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2015;(79):1-16.

8. Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, MacDonald R, et al. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD005614.

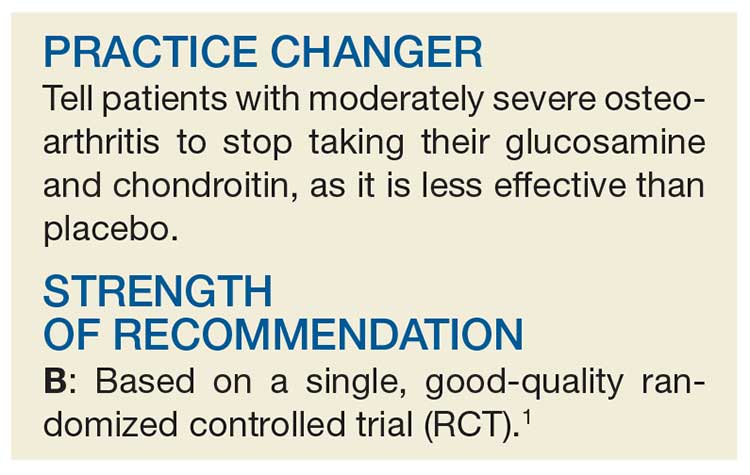

PRACTICE CHANGER

Tell patients with moderately severe osteoarthritis to stop taking their glucosamine and chondroitin as it is less effective than placebo.1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

B: Based on single, good-quality randomized controlled trial.

Roman-Blas JA, Castañeda S, Sánchez-Pernaute O, et al. Combined treatment with chondroitin sulfate and glucosamine sulfate shows no superiority over placebo for reduction of joint pain and functional impairment in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a six-month multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69:77-85.

Does exercise relieve vasomotor menopausal symptoms?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 733 patients examined the effectiveness of any type of exercise in decreasing vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The studies compared exercise—defined as structured exercise or physical activity through active living—with no active treatment, yoga, or hormone therapy (HT) over a 3- to 24-month follow-up period.

Three trials of 454 women that compared exercise with no active treatment found no difference between groups in frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms (standard mean difference [SMD]= -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.33 to 0.13).

Two trials with 279 women that compared exercise with yoga didn’t find a difference in reported frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms between the groups (SMD= -0.03; 95% CI, -0.45 to 0.38).

One small trial (14 women) of exercise and HT found that HT patients reported decreased frequency of flushes over 24 hours compared with the exercise group (mean difference [MD]=5.8; 95% CI, 3.17-8.43).

Overall, the evidence was of low quality because of heterogeneity in study design.1

Two exercise interventions fail to reduce symptoms

A 2014 RCT, published after the Cochrane search date, investigated exercise as a treatment for VMS in 261 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women ages 48 to 57 years.2 Patients had a history of at least 5 hot flashes or night sweats per day and hadn’t taken HT in the previous 3 months.

The women were randomized to one of 2 exercise interventions or a control group. The exercise interventions both entailed 2 one-on-one consultations with a physical activity facilitator and use of a pedometer. Patients were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 3 days a week during Weeks 1 through 12, then increase the frequency to 3 to 5 days a week during Weeks 13 through 24. In one intervention arm, the women also received an informational DVD and 5 educational leaflets.

In the other arm, they were invited to attend 3 exercise support groups in their local community. The control group was offered an opportunity for exercise consultation and given a pedometer at the end of the study.

At the end of the 6-month intervention, neither exercise intervention significantly decreased self-reported hot flashes/night sweats per week compared with the control group (DVD exercise arm vs control: MD= -8.9; 95% CI, -20 to 2.2; social support exercise arm vs control: MD= -5.2; 95% CI, -16.7 to 6.3). The study also found no difference in hot flashes/night sweats per week at 12-month follow-up between the DVD exercise arm and controls (MD= -3.2; 95% CI, -12.7 to 6.4) and the social-support group and controls (MD= -3.5; 95% CI, -13.2 to 6.1).

Drug therapy relieves symptoms, but other methods—not so much

An analysis of pooled individual data from 3 RCTs compared exercise with 5 other interventions for VMS in 899 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 Patients had at least 14 bothersome symptoms per week.

The 6 interventions ranged from nonpharmacologic therapies, such as aerobic exercise and yoga, to pharmacologic treatments, including escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/d, venlafaxine 75 mg/d, oral estradiol (E2) 0.5 mg/d, and omega-3 supplementation 1.8 g/d. The primary outcome was a change in VMS frequency and bother as assessed by a symptom diary over the 4- to 12-week follow-up.

The analysis found a significant 6-week reduction in daily VMS frequency relative to placebo for escitalopram (MD= -1.4; 95% CI, -2.7 to -0.2), low-dose E2 (MD= -1.9; 95% CI, -2.9 to -0.9), and venlafaxine (MD= -1.3; 95% CI, -2.3 to -0.3). However, no difference in VMS frequency or bother was found with exercise (MD= -0.4; 95% CI, -1.1 to 0.3), yoga (MD= -0.6; 95% CI, -1.3 to 0.1), or omega-3 supplementation (MD= 0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) doesn’t offer specific recommendations regarding exercise as a treatment for symptoms of menopause. The 2014 ACOG guidelines for managing symptoms report that data don’t support phytoestrogens, supplements, or lifestyle modifications (Level B, based on limited or inconsistent evidence). ACOG recommends basic palliative measures such as drinking cool drinks and decreasing layers of clothing (Level B).4

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ recommendations don’t mention exercise as a menopause therapy.5

The North American Menopause Society’s 2015 statement regarding the nonhormonal treatment of menopause symptoms doesn’t recommend exercise as an effective therapy because of insufficient or inconclusive data.6

1. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Thomas A, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD006108.

2. Daley AJ, Thomas A, Roalfe AK, et al. The effectiveness of exercise as treatment for vasomotor menopausal symptoms: randomized controlled trial. BJOG. 2015;122:565-575.

3. Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Ensrud KE, et al. Pooled analysis of six pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:413-422.

4. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

5. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Ginzburg SB, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:949-954.

6. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:1155-1172.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 733 patients examined the effectiveness of any type of exercise in decreasing vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The studies compared exercise—defined as structured exercise or physical activity through active living—with no active treatment, yoga, or hormone therapy (HT) over a 3- to 24-month follow-up period.

Three trials of 454 women that compared exercise with no active treatment found no difference between groups in frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms (standard mean difference [SMD]= -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.33 to 0.13).

Two trials with 279 women that compared exercise with yoga didn’t find a difference in reported frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms between the groups (SMD= -0.03; 95% CI, -0.45 to 0.38).

One small trial (14 women) of exercise and HT found that HT patients reported decreased frequency of flushes over 24 hours compared with the exercise group (mean difference [MD]=5.8; 95% CI, 3.17-8.43).

Overall, the evidence was of low quality because of heterogeneity in study design.1

Two exercise interventions fail to reduce symptoms

A 2014 RCT, published after the Cochrane search date, investigated exercise as a treatment for VMS in 261 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women ages 48 to 57 years.2 Patients had a history of at least 5 hot flashes or night sweats per day and hadn’t taken HT in the previous 3 months.

The women were randomized to one of 2 exercise interventions or a control group. The exercise interventions both entailed 2 one-on-one consultations with a physical activity facilitator and use of a pedometer. Patients were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 3 days a week during Weeks 1 through 12, then increase the frequency to 3 to 5 days a week during Weeks 13 through 24. In one intervention arm, the women also received an informational DVD and 5 educational leaflets.

In the other arm, they were invited to attend 3 exercise support groups in their local community. The control group was offered an opportunity for exercise consultation and given a pedometer at the end of the study.

At the end of the 6-month intervention, neither exercise intervention significantly decreased self-reported hot flashes/night sweats per week compared with the control group (DVD exercise arm vs control: MD= -8.9; 95% CI, -20 to 2.2; social support exercise arm vs control: MD= -5.2; 95% CI, -16.7 to 6.3). The study also found no difference in hot flashes/night sweats per week at 12-month follow-up between the DVD exercise arm and controls (MD= -3.2; 95% CI, -12.7 to 6.4) and the social-support group and controls (MD= -3.5; 95% CI, -13.2 to 6.1).

Drug therapy relieves symptoms, but other methods—not so much

An analysis of pooled individual data from 3 RCTs compared exercise with 5 other interventions for VMS in 899 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 Patients had at least 14 bothersome symptoms per week.

The 6 interventions ranged from nonpharmacologic therapies, such as aerobic exercise and yoga, to pharmacologic treatments, including escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/d, venlafaxine 75 mg/d, oral estradiol (E2) 0.5 mg/d, and omega-3 supplementation 1.8 g/d. The primary outcome was a change in VMS frequency and bother as assessed by a symptom diary over the 4- to 12-week follow-up.

The analysis found a significant 6-week reduction in daily VMS frequency relative to placebo for escitalopram (MD= -1.4; 95% CI, -2.7 to -0.2), low-dose E2 (MD= -1.9; 95% CI, -2.9 to -0.9), and venlafaxine (MD= -1.3; 95% CI, -2.3 to -0.3). However, no difference in VMS frequency or bother was found with exercise (MD= -0.4; 95% CI, -1.1 to 0.3), yoga (MD= -0.6; 95% CI, -1.3 to 0.1), or omega-3 supplementation (MD= 0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) doesn’t offer specific recommendations regarding exercise as a treatment for symptoms of menopause. The 2014 ACOG guidelines for managing symptoms report that data don’t support phytoestrogens, supplements, or lifestyle modifications (Level B, based on limited or inconsistent evidence). ACOG recommends basic palliative measures such as drinking cool drinks and decreasing layers of clothing (Level B).4

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ recommendations don’t mention exercise as a menopause therapy.5

The North American Menopause Society’s 2015 statement regarding the nonhormonal treatment of menopause symptoms doesn’t recommend exercise as an effective therapy because of insufficient or inconclusive data.6

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 Cochrane meta-analysis of 5 RCTs with a total of 733 patients examined the effectiveness of any type of exercise in decreasing vasomotor symptoms in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.1 The studies compared exercise—defined as structured exercise or physical activity through active living—with no active treatment, yoga, or hormone therapy (HT) over a 3- to 24-month follow-up period.

Three trials of 454 women that compared exercise with no active treatment found no difference between groups in frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms (standard mean difference [SMD]= -0.10; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.33 to 0.13).

Two trials with 279 women that compared exercise with yoga didn’t find a difference in reported frequency or intensity of vasomotor symptoms between the groups (SMD= -0.03; 95% CI, -0.45 to 0.38).

One small trial (14 women) of exercise and HT found that HT patients reported decreased frequency of flushes over 24 hours compared with the exercise group (mean difference [MD]=5.8; 95% CI, 3.17-8.43).

Overall, the evidence was of low quality because of heterogeneity in study design.1

Two exercise interventions fail to reduce symptoms

A 2014 RCT, published after the Cochrane search date, investigated exercise as a treatment for VMS in 261 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women ages 48 to 57 years.2 Patients had a history of at least 5 hot flashes or night sweats per day and hadn’t taken HT in the previous 3 months.

The women were randomized to one of 2 exercise interventions or a control group. The exercise interventions both entailed 2 one-on-one consultations with a physical activity facilitator and use of a pedometer. Patients were encouraged to perform 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise 3 days a week during Weeks 1 through 12, then increase the frequency to 3 to 5 days a week during Weeks 13 through 24. In one intervention arm, the women also received an informational DVD and 5 educational leaflets.

In the other arm, they were invited to attend 3 exercise support groups in their local community. The control group was offered an opportunity for exercise consultation and given a pedometer at the end of the study.

At the end of the 6-month intervention, neither exercise intervention significantly decreased self-reported hot flashes/night sweats per week compared with the control group (DVD exercise arm vs control: MD= -8.9; 95% CI, -20 to 2.2; social support exercise arm vs control: MD= -5.2; 95% CI, -16.7 to 6.3). The study also found no difference in hot flashes/night sweats per week at 12-month follow-up between the DVD exercise arm and controls (MD= -3.2; 95% CI, -12.7 to 6.4) and the social-support group and controls (MD= -3.5; 95% CI, -13.2 to 6.1).

Drug therapy relieves symptoms, but other methods—not so much

An analysis of pooled individual data from 3 RCTs compared exercise with 5 other interventions for VMS in 899 perimenopausal and postmenopausal women.3 Patients had at least 14 bothersome symptoms per week.

The 6 interventions ranged from nonpharmacologic therapies, such as aerobic exercise and yoga, to pharmacologic treatments, including escitalopram 10 to 20 mg/d, venlafaxine 75 mg/d, oral estradiol (E2) 0.5 mg/d, and omega-3 supplementation 1.8 g/d. The primary outcome was a change in VMS frequency and bother as assessed by a symptom diary over the 4- to 12-week follow-up.

The analysis found a significant 6-week reduction in daily VMS frequency relative to placebo for escitalopram (MD= -1.4; 95% CI, -2.7 to -0.2), low-dose E2 (MD= -1.9; 95% CI, -2.9 to -0.9), and venlafaxine (MD= -1.3; 95% CI, -2.3 to -0.3). However, no difference in VMS frequency or bother was found with exercise (MD= -0.4; 95% CI, -1.1 to 0.3), yoga (MD= -0.6; 95% CI, -1.3 to 0.1), or omega-3 supplementation (MD= 0.2; 95% CI, -0.4 to 0.8).

RECOMMENDATIONS

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) doesn’t offer specific recommendations regarding exercise as a treatment for symptoms of menopause. The 2014 ACOG guidelines for managing symptoms report that data don’t support phytoestrogens, supplements, or lifestyle modifications (Level B, based on limited or inconsistent evidence). ACOG recommends basic palliative measures such as drinking cool drinks and decreasing layers of clothing (Level B).4

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists’ recommendations don’t mention exercise as a menopause therapy.5

The North American Menopause Society’s 2015 statement regarding the nonhormonal treatment of menopause symptoms doesn’t recommend exercise as an effective therapy because of insufficient or inconclusive data.6

1. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Thomas A, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD006108.

2. Daley AJ, Thomas A, Roalfe AK, et al. The effectiveness of exercise as treatment for vasomotor menopausal symptoms: randomized controlled trial. BJOG. 2015;122:565-575.

3. Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Ensrud KE, et al. Pooled analysis of six pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:413-422.

4. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

5. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Ginzburg SB, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:949-954.

6. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:1155-1172.

1. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H, Thomas A, et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD006108.

2. Daley AJ, Thomas A, Roalfe AK, et al. The effectiveness of exercise as treatment for vasomotor menopausal symptoms: randomized controlled trial. BJOG. 2015;122:565-575.

3. Guthrie KA, LaCroix AZ, Ensrud KE, et al. Pooled analysis of six pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions for vasomotor symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;126:413-422.

4. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123:202-216.

5. Goodman NF, Cobin RH, Ginzburg SB, et al; American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists Medical Guidelines for Clinical Practice for the diagnosis and treatment of menopause: executive summary of recommendations. Endocr Pract. 2011;17:949-954.

6. Nonhormonal management of menopause-associated vasomotor symptoms: 2015 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause. 2015;22:1155-1172.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Exercise doesn’t decrease the frequency or severity of vasomotor menopausal symptoms (VMS) in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (strength of recommendation: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and consistent RCT).