User login

The Impact of COVID-19 on Colorectal Cancer Screening Programs

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-164. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

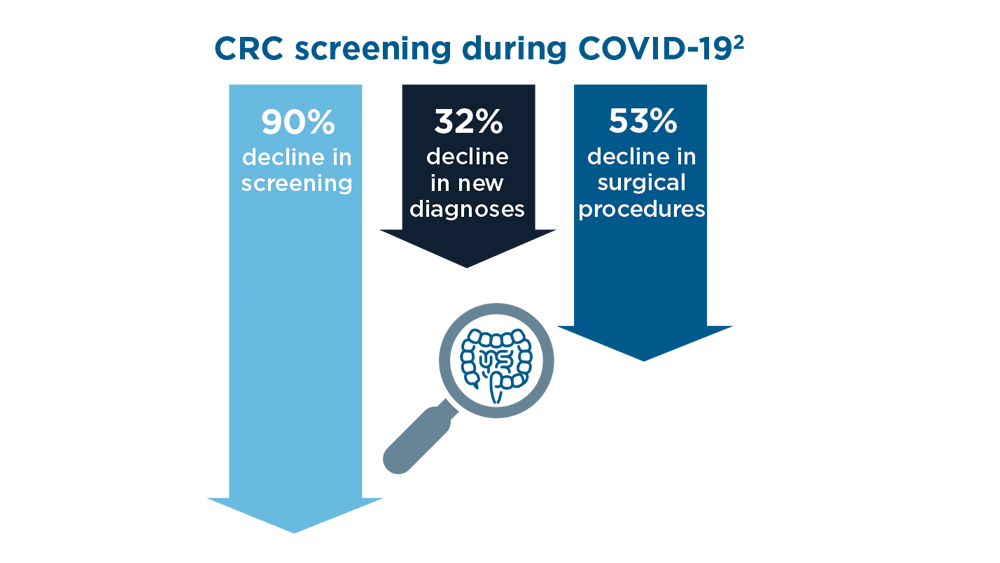

- Issaka RB, Somsouk M. Colorectal cancer screening and prevention in the COVID-19 era. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200588. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0588

- Balzora S, Issaka RB, Anyane-Yeboa A, Gray DM 2nd, May FP. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer disparities and the way forward. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):946-950. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042

- Truman BI, Chang MH, Moonesinghe R. Provisional COVID-19 age-adjusted death rates, by race and ethnicity – United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(17):601-605. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7117e2

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns – United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575-582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

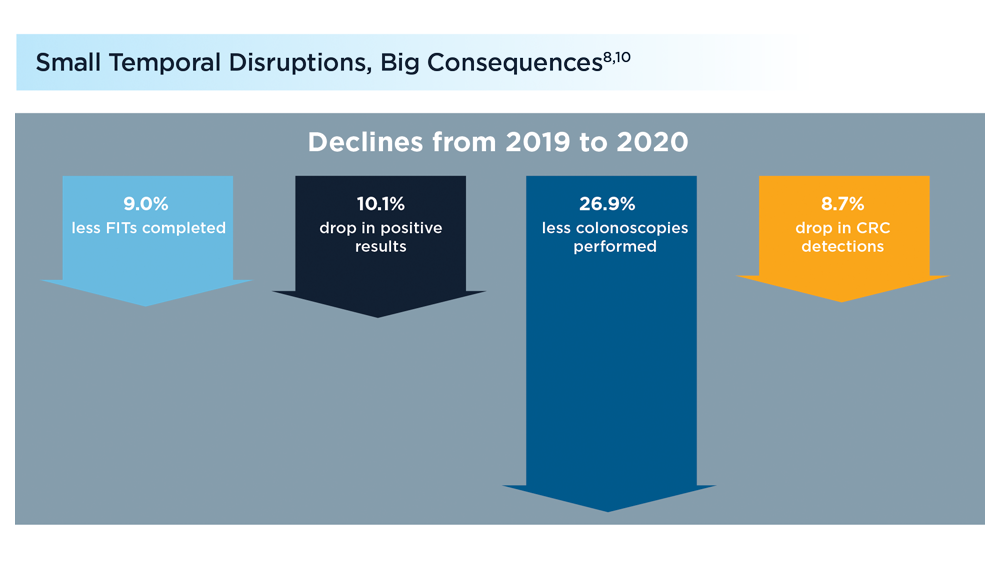

- Fedewa SA, Star J, Bandi P, et al. Changes in cancer screening in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2215490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15490

- Levin TR, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Effects of organized colorectal cancer screening on cancer incidence and mortality in a large community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1383-1391.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.017

- Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Zhao W, Lau Y, Jensen CD, Levin TR. Association between improved colorectal screening and racial disparities. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(8):796-798. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2112409

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Issaka RB, Taylor P, Baxi A, Inadomi JM, Ramsey SD, Roth J. Model-based estimation of colorectal cancer screening and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216454. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6454

- Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, et al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–sponsored summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):283-298. doi:10.3322/caac.21615

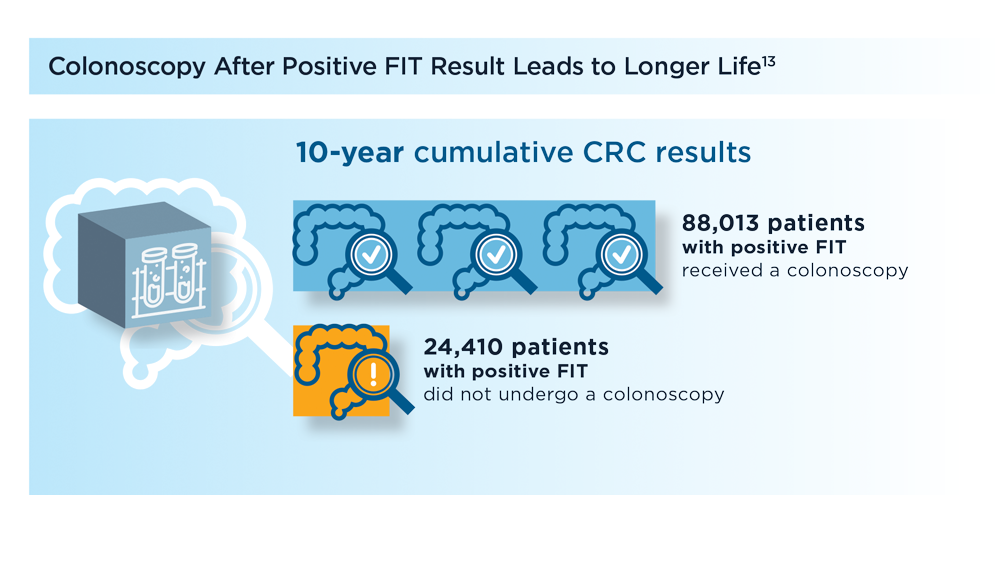

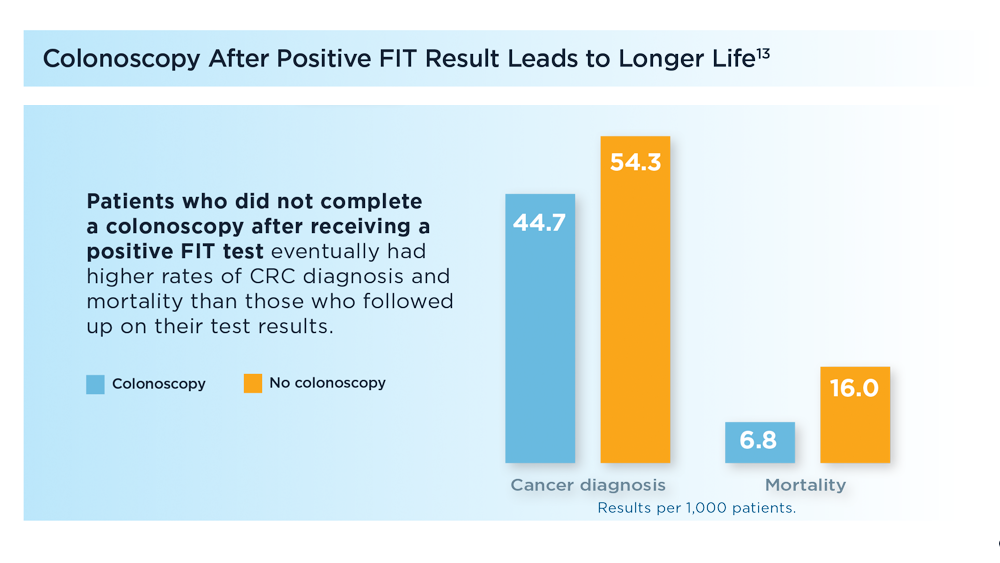

- Zorzi M, Battagello J, Selby K, et al. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut. 2022;71(3):561-567. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322192

- Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Brill JV, et al. Reducing the burden of colorectal cancer: AGA position statements. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(2):520-526. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.011

- Bell-Brown A, Chew L, Weiner BJ, et al. Operationalizing a rideshare intervention for colonoscopy completion: barriers, facilitators, and process recommendations. Front Health Serv. 2022;1:799816. doi:10.3389/frhs.2021.799816

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-164. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

- Issaka RB, Somsouk M. Colorectal cancer screening and prevention in the COVID-19 era. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200588. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0588

- Balzora S, Issaka RB, Anyane-Yeboa A, Gray DM 2nd, May FP. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer disparities and the way forward. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):946-950. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042

- Truman BI, Chang MH, Moonesinghe R. Provisional COVID-19 age-adjusted death rates, by race and ethnicity – United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(17):601-605. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7117e2

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns – United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575-582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Fedewa SA, Star J, Bandi P, et al. Changes in cancer screening in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2215490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15490

- Levin TR, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Effects of organized colorectal cancer screening on cancer incidence and mortality in a large community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1383-1391.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.017

- Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Zhao W, Lau Y, Jensen CD, Levin TR. Association between improved colorectal screening and racial disparities. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(8):796-798. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2112409

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Issaka RB, Taylor P, Baxi A, Inadomi JM, Ramsey SD, Roth J. Model-based estimation of colorectal cancer screening and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216454. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6454

- Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, et al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–sponsored summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):283-298. doi:10.3322/caac.21615

- Zorzi M, Battagello J, Selby K, et al. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut. 2022;71(3):561-567. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322192

- Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Brill JV, et al. Reducing the burden of colorectal cancer: AGA position statements. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(2):520-526. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.011

- Bell-Brown A, Chew L, Weiner BJ, et al. Operationalizing a rideshare intervention for colonoscopy completion: barriers, facilitators, and process recommendations. Front Health Serv. 2022;1:799816. doi:10.3389/frhs.2021.799816

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(3):145-164. doi:10.3322/caac.21601

- Issaka RB, Somsouk M. Colorectal cancer screening and prevention in the COVID-19 era. JAMA Health Forum. 2020;1(5):e200588. doi:10.1001/jamahealthforum.2020.0588

- Balzora S, Issaka RB, Anyane-Yeboa A, Gray DM 2nd, May FP. Impact of COVID-19 on colorectal cancer disparities and the way forward. Gastrointest Endosc. 2020;92(4):946-950. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2020.06.042

- Truman BI, Chang MH, Moonesinghe R. Provisional COVID-19 age-adjusted death rates, by race and ethnicity – United States, 2020–2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(17):601-605. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7117e2

- Czeisler MÉ, Marynak K, Clarke KEN, et al. Delay or avoidance of medical care because of COVID-19-related concerns – United States, June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(36):1250-1257. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6936a4

- Inadomi JM, Vijan S, Janz NK, et al. Adherence to colorectal cancer screening: a randomized clinical trial of competing strategies. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(7):575-582. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2012.332

- Fedewa SA, Star J, Bandi P, et al. Changes in cancer screening in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(6):e2215490. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.15490

- Levin TR, Corley DA, Jensen CD, et al. Effects of organized colorectal cancer screening on cancer incidence and mortality in a large community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(5):1383-1391.e5. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.07.017

- Doubeni CA, Corley DA, Zhao W, Lau Y, Jensen CD, Levin TR. Association between improved colorectal screening and racial disparities. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(8):796-798. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2112409

- Lee JK, Lam AY, Jensen CD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on fecal immunochemical testing, colonoscopy services, and colorectal neoplasia detection in a large United States community-based population. Gastroenterology. 2022;S0016-5085(22)00503-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.014

- Issaka RB, Taylor P, Baxi A, Inadomi JM, Ramsey SD, Roth J. Model-based estimation of colorectal cancer screening and outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(4):e216454. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6454

- Gupta S, Coronado GD, Argenbright K, et al. Mailed fecal immunochemical test outreach for colorectal cancer screening: summary of a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–sponsored summit. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(4):283-298. doi:10.3322/caac.21615

- Zorzi M, Battagello J, Selby K, et al. Non-compliance with colonoscopy after a positive faecal immunochemical test doubles the risk of dying from colorectal cancer. Gut. 2022;71(3):561-567. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322192

- Lieberman D, Ladabaum U, Brill JV, et al. Reducing the burden of colorectal cancer: AGA position statements. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(2):520-526. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2022.05.011

- Bell-Brown A, Chew L, Weiner BJ, et al. Operationalizing a rideshare intervention for colonoscopy completion: barriers, facilitators, and process recommendations. Front Health Serv. 2022;1:799816. doi:10.3389/frhs.2021.799816

Microaggressions, racism, and antiracism: The role of gastroenterology

On a busy call day, Oviea (a second-year gastroenterology fellow), paused in the hallway to listen to a conversation between an endoscopy nurse and a patient. The nurse was requesting the patient’s permission for a gastroenterology fellow to participate in their care and the patient, well acquainted with the role from prior procedures, immediately agreed. Oviea entered the patient’s room, introduced himself as “Dr. Akpotaire, the gastroenterology fellow,” as he had with hundreds of other patients during his fellowship, and completed the informed consent. The interaction was brief but pleasant. As Oviea was leaving the room, the patient asked: “When will I meet the doctor”?

This question was familiar to Oviea. Despite always introducing himself by title and wearing matching identification, many patients had dismissed his credentials since graduating from medical school. His answer was equally familiar: “I am a doctor, and Dr. X, the supervising physician, will meet you soon.” With the patient seemingly placated, Oviea delivered the consent form to the procedure room. Minutes later, he was surprised to learn that the patient specifically requested that he not be allowed to participate in their care. This in combination with the patient’s initial dismissal of Oviea’s credentials, left a sting. While none of the other team members outwardly questioned the reason for the patient’s change of heart, Oviea continued to wonder if the patient’s decision was because of his race.

Beyond gastroenterology, similar experiences are common in other spheres. The Twitter thread #BlackintheIvory recounts stories of microaggressions and structural racism in medicine and academia. The cumulative toll of these experiences leads to departures of Black physicians including Uché Blackstock, MD;1 Aysha Khoury, MD, MPH;2 Ben Danielson, MD;3 Princess Dennar, MD;4 and others.

Microaggressions as proxy for bias

The term microaggression was coined by Chester Pierce, MD, the first Black tenured professor at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1970’s, to describe the frequent, yet subtle dismissals Black Americans experienced in society. Over time, the term has been expanded to include “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults” to any marginalized group.5

While the term microaggressions is useful in contextualizing individual experiences, it narrowly focuses on conscious or unconscious interpersonal prejudices. In medicine, this misdirects attention away from the policies and practices that create and reinforce prejudices; these policies and practices do so by systematically excluding underrepresented minority (URM) physicians,6 defined by the American Association of Medical Colleges as physicians who are Black, Hispanic, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives,7 from the medical workforce. Ultimately, this leads to and exacerbates poor health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients.

Microaggressions represent our society’s deepest and oldest biases and are rooted in structural racism, as well as misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.8 For URM physicians, experiences like the example above are frequently caused by structural racism.

Structural racism in medicine

Structural racism refers to the policies, practices, cultural representations, and norms that reinforce inequities by providing privileges to White people at the disadvantage of non-White people.9 In 1910, Abraham Flexner, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and the American Medical Association, wrote that African American physicians should be trained in hygiene rather than surgery and should primarily serve as “sanitarians” whose purpose was to “protect Whites” from common diseases like tuberculosis.10 The 1910 Flexner Report also emphasized the importance of prerequisite basic sciences education and recommended that only two of the seven existing Black medical schools remain open because Flexner believed that only these schools had the potential to meet the new requirements for medical education.11 A recent analysis found that, had the other five medical schools affiliated with historically Black colleges and universities remained open, this would have resulted in an additional 33,315 Black medical school graduates by 2019.12 Structural racism explains why the majority of practicing physicians, medical educators, National Institutes of Health–funded researchers, and hospital executives are White and, similarly, why White patients are overrepresented in clinical trials, have better health outcomes, and live longer lives than several racial and ethnic minority groups.13

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and the inequitable toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black, Hispanic, and Native American people renewed the dialogue regarding structural racism in America. Beyond criminal justice and police reform, the current social justice movement demands that structural racism is examined in all spheres. In medicine and health care, acknowledging the history of exclusion and exploitation of Black people and other URM groups is an important first step, but this must be followed by a commitment to an antiracist future for the benefit of all medical professionals and patients.14,15

Antiracism as a path forward

Antiracism refers to actions and policies that seek to dismantle structural racism. While individuals can and should engage in antiracist actions, it is equally important for organizations and government to actively participate in this process as well.

Individual and interpersonal levels

Gastroenterologists should advocate an end to racist practices within their organizations (e.g., unjustified use of race-based corrections in diagnostic algorithms and practice guidelines),16 and interrupt microaggressions and racist actions in real time (e.g., overpolicing of underrepresented groups in health care settings).17 Gastroenterologists from underrepresented groups may also need to unlearn internalized racism, which is defined as acceptance by members of disadvantaged races of the negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.18

Organizational level

Gastroenterology divisions and practices must ensure that the entire workforce, including leadership, reflects the diversity of our country. Underrepresented groups represent 33% of the U.S. population, but only 9.1% of gastroenterology fellows and 10% of gastroenterology faculty are from underrepresented groups.19 In addition to diversifying the field of gastroenterology through financial and operational support of pipeline educational programs, organizations should also promote the scholarship of URM groups, whose work is often undervalued, and redistribute power by elevating voices that have been historically absent.20 Gastroenterology practices should also collect high-quality patient data disaggregated by demographic factors. Doing so will enable rapid identification of disparate health outcomes by demographic variables and inform interventions to eliminate identified disparities.

Government level

The “Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” issued by President Biden on Jan. 20, 2021, is an example of how government can promote antiracism.21 The executive order states that domestic policies cause group inequities and calls for the removal of systemic barriers in current and future domestic policies. The executive order outlines several additional ways to improve equity in current and future policy, including engagement, consultation, and coordination with members of underserved communities. The details outlined in the executive order should serve as the foundation for establishing new standards at the state, county, and city levels as well. Gastroenterologists can influence government by voting for officials at all levels that support and promote these standards.

Conclusion

Beyond calling out microaggressions in real time, we must also interrogate the biases, policies, and practices that support them in medicine and beyond. As Black gastroenterologists who have experienced microaggressions and overt acts of racism, we ground Oviea’s experience in structural racism and offer strategies that individuals, organizations, and governing institutions can adopt toward an antiracist future. This model can be applied to experiences rooted in misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.

As a nation, we must make an active and collective choice to address structural racism. In health care, doing so will strengthen communities, enhance the lived experiences of URM physician colleagues, and save patient lives. Gastroenterologists, as trusted health care providers, are uniquely positioned to lead the way.

Dr. Akpotaire is a second-year GI fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Issaka is an assistant professor with both the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington.

References

1. Blackstock U. “Why Black doctors like me are leaving faculty positions in academic medical centers.” STAT News, 2020.

2. Asare JG. “One Doctor Shares Her Story of Racism in Medicine.” Forbes. 2021 Feb 1.

3. Kroman D. “Revered doctor steps down, accusing Seattle Children’s Hospital of racism.” Crosscut. 2020 Dec 31.

4. United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana. Princess Dennar, M.D. v. The Administrators of the Tulane Educational Fund, 2020.

5. Sue DW. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2010.

6. Boyd RW. Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):2484-5.

7. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine Facts and Figures 2019. Washington, D.C., 2019.

8. Overland MK et al. PM R. 2019 Sep;11(9):1004-12.

9. Jones CP. Ethn Dis. 2018 Aug 9;28(Suppl 1):231-4.

10. Hlavinka E. “Racial Bias in Flexner Report Permeates Medical Education Today.” Medpage Today. 2020 Jun 18.

11. Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York: 1910. Republished: Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

12. Campbell KM et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3;3(8):e2015220.

13. Malat J et al. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Feb;199:148-56.

14. Kendi IX. How to be an antiracist. New York: Random House Books, 2019.

15. Gray DM 2nd et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Oct;17(10):589-90.

16. Vyas DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 27;383(9):874-82.

17. Green CR et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018 Feb;110(1):37-43.

18. Jones CP. Am J Public Health. 2000 Aug;90(8):1212-5.

19. Anyane-Yeboa A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug;115(8):1147-9.

20. Issaka RB. JAMA. 2020 Aug 11;324(6):556-7.

21. Biden JR. Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Washington, D.C.: The White House, 2021.

On a busy call day, Oviea (a second-year gastroenterology fellow), paused in the hallway to listen to a conversation between an endoscopy nurse and a patient. The nurse was requesting the patient’s permission for a gastroenterology fellow to participate in their care and the patient, well acquainted with the role from prior procedures, immediately agreed. Oviea entered the patient’s room, introduced himself as “Dr. Akpotaire, the gastroenterology fellow,” as he had with hundreds of other patients during his fellowship, and completed the informed consent. The interaction was brief but pleasant. As Oviea was leaving the room, the patient asked: “When will I meet the doctor”?

This question was familiar to Oviea. Despite always introducing himself by title and wearing matching identification, many patients had dismissed his credentials since graduating from medical school. His answer was equally familiar: “I am a doctor, and Dr. X, the supervising physician, will meet you soon.” With the patient seemingly placated, Oviea delivered the consent form to the procedure room. Minutes later, he was surprised to learn that the patient specifically requested that he not be allowed to participate in their care. This in combination with the patient’s initial dismissal of Oviea’s credentials, left a sting. While none of the other team members outwardly questioned the reason for the patient’s change of heart, Oviea continued to wonder if the patient’s decision was because of his race.

Beyond gastroenterology, similar experiences are common in other spheres. The Twitter thread #BlackintheIvory recounts stories of microaggressions and structural racism in medicine and academia. The cumulative toll of these experiences leads to departures of Black physicians including Uché Blackstock, MD;1 Aysha Khoury, MD, MPH;2 Ben Danielson, MD;3 Princess Dennar, MD;4 and others.

Microaggressions as proxy for bias

The term microaggression was coined by Chester Pierce, MD, the first Black tenured professor at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1970’s, to describe the frequent, yet subtle dismissals Black Americans experienced in society. Over time, the term has been expanded to include “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults” to any marginalized group.5

While the term microaggressions is useful in contextualizing individual experiences, it narrowly focuses on conscious or unconscious interpersonal prejudices. In medicine, this misdirects attention away from the policies and practices that create and reinforce prejudices; these policies and practices do so by systematically excluding underrepresented minority (URM) physicians,6 defined by the American Association of Medical Colleges as physicians who are Black, Hispanic, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives,7 from the medical workforce. Ultimately, this leads to and exacerbates poor health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients.

Microaggressions represent our society’s deepest and oldest biases and are rooted in structural racism, as well as misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.8 For URM physicians, experiences like the example above are frequently caused by structural racism.

Structural racism in medicine

Structural racism refers to the policies, practices, cultural representations, and norms that reinforce inequities by providing privileges to White people at the disadvantage of non-White people.9 In 1910, Abraham Flexner, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and the American Medical Association, wrote that African American physicians should be trained in hygiene rather than surgery and should primarily serve as “sanitarians” whose purpose was to “protect Whites” from common diseases like tuberculosis.10 The 1910 Flexner Report also emphasized the importance of prerequisite basic sciences education and recommended that only two of the seven existing Black medical schools remain open because Flexner believed that only these schools had the potential to meet the new requirements for medical education.11 A recent analysis found that, had the other five medical schools affiliated with historically Black colleges and universities remained open, this would have resulted in an additional 33,315 Black medical school graduates by 2019.12 Structural racism explains why the majority of practicing physicians, medical educators, National Institutes of Health–funded researchers, and hospital executives are White and, similarly, why White patients are overrepresented in clinical trials, have better health outcomes, and live longer lives than several racial and ethnic minority groups.13

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and the inequitable toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black, Hispanic, and Native American people renewed the dialogue regarding structural racism in America. Beyond criminal justice and police reform, the current social justice movement demands that structural racism is examined in all spheres. In medicine and health care, acknowledging the history of exclusion and exploitation of Black people and other URM groups is an important first step, but this must be followed by a commitment to an antiracist future for the benefit of all medical professionals and patients.14,15

Antiracism as a path forward

Antiracism refers to actions and policies that seek to dismantle structural racism. While individuals can and should engage in antiracist actions, it is equally important for organizations and government to actively participate in this process as well.

Individual and interpersonal levels

Gastroenterologists should advocate an end to racist practices within their organizations (e.g., unjustified use of race-based corrections in diagnostic algorithms and practice guidelines),16 and interrupt microaggressions and racist actions in real time (e.g., overpolicing of underrepresented groups in health care settings).17 Gastroenterologists from underrepresented groups may also need to unlearn internalized racism, which is defined as acceptance by members of disadvantaged races of the negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.18

Organizational level

Gastroenterology divisions and practices must ensure that the entire workforce, including leadership, reflects the diversity of our country. Underrepresented groups represent 33% of the U.S. population, but only 9.1% of gastroenterology fellows and 10% of gastroenterology faculty are from underrepresented groups.19 In addition to diversifying the field of gastroenterology through financial and operational support of pipeline educational programs, organizations should also promote the scholarship of URM groups, whose work is often undervalued, and redistribute power by elevating voices that have been historically absent.20 Gastroenterology practices should also collect high-quality patient data disaggregated by demographic factors. Doing so will enable rapid identification of disparate health outcomes by demographic variables and inform interventions to eliminate identified disparities.

Government level

The “Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” issued by President Biden on Jan. 20, 2021, is an example of how government can promote antiracism.21 The executive order states that domestic policies cause group inequities and calls for the removal of systemic barriers in current and future domestic policies. The executive order outlines several additional ways to improve equity in current and future policy, including engagement, consultation, and coordination with members of underserved communities. The details outlined in the executive order should serve as the foundation for establishing new standards at the state, county, and city levels as well. Gastroenterologists can influence government by voting for officials at all levels that support and promote these standards.

Conclusion

Beyond calling out microaggressions in real time, we must also interrogate the biases, policies, and practices that support them in medicine and beyond. As Black gastroenterologists who have experienced microaggressions and overt acts of racism, we ground Oviea’s experience in structural racism and offer strategies that individuals, organizations, and governing institutions can adopt toward an antiracist future. This model can be applied to experiences rooted in misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.

As a nation, we must make an active and collective choice to address structural racism. In health care, doing so will strengthen communities, enhance the lived experiences of URM physician colleagues, and save patient lives. Gastroenterologists, as trusted health care providers, are uniquely positioned to lead the way.

Dr. Akpotaire is a second-year GI fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Issaka is an assistant professor with both the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington.

References

1. Blackstock U. “Why Black doctors like me are leaving faculty positions in academic medical centers.” STAT News, 2020.

2. Asare JG. “One Doctor Shares Her Story of Racism in Medicine.” Forbes. 2021 Feb 1.

3. Kroman D. “Revered doctor steps down, accusing Seattle Children’s Hospital of racism.” Crosscut. 2020 Dec 31.

4. United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana. Princess Dennar, M.D. v. The Administrators of the Tulane Educational Fund, 2020.

5. Sue DW. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2010.

6. Boyd RW. Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):2484-5.

7. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine Facts and Figures 2019. Washington, D.C., 2019.

8. Overland MK et al. PM R. 2019 Sep;11(9):1004-12.

9. Jones CP. Ethn Dis. 2018 Aug 9;28(Suppl 1):231-4.

10. Hlavinka E. “Racial Bias in Flexner Report Permeates Medical Education Today.” Medpage Today. 2020 Jun 18.

11. Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York: 1910. Republished: Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

12. Campbell KM et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3;3(8):e2015220.

13. Malat J et al. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Feb;199:148-56.

14. Kendi IX. How to be an antiracist. New York: Random House Books, 2019.

15. Gray DM 2nd et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Oct;17(10):589-90.

16. Vyas DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 27;383(9):874-82.

17. Green CR et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018 Feb;110(1):37-43.

18. Jones CP. Am J Public Health. 2000 Aug;90(8):1212-5.

19. Anyane-Yeboa A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug;115(8):1147-9.

20. Issaka RB. JAMA. 2020 Aug 11;324(6):556-7.

21. Biden JR. Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Washington, D.C.: The White House, 2021.

On a busy call day, Oviea (a second-year gastroenterology fellow), paused in the hallway to listen to a conversation between an endoscopy nurse and a patient. The nurse was requesting the patient’s permission for a gastroenterology fellow to participate in their care and the patient, well acquainted with the role from prior procedures, immediately agreed. Oviea entered the patient’s room, introduced himself as “Dr. Akpotaire, the gastroenterology fellow,” as he had with hundreds of other patients during his fellowship, and completed the informed consent. The interaction was brief but pleasant. As Oviea was leaving the room, the patient asked: “When will I meet the doctor”?

This question was familiar to Oviea. Despite always introducing himself by title and wearing matching identification, many patients had dismissed his credentials since graduating from medical school. His answer was equally familiar: “I am a doctor, and Dr. X, the supervising physician, will meet you soon.” With the patient seemingly placated, Oviea delivered the consent form to the procedure room. Minutes later, he was surprised to learn that the patient specifically requested that he not be allowed to participate in their care. This in combination with the patient’s initial dismissal of Oviea’s credentials, left a sting. While none of the other team members outwardly questioned the reason for the patient’s change of heart, Oviea continued to wonder if the patient’s decision was because of his race.

Beyond gastroenterology, similar experiences are common in other spheres. The Twitter thread #BlackintheIvory recounts stories of microaggressions and structural racism in medicine and academia. The cumulative toll of these experiences leads to departures of Black physicians including Uché Blackstock, MD;1 Aysha Khoury, MD, MPH;2 Ben Danielson, MD;3 Princess Dennar, MD;4 and others.

Microaggressions as proxy for bias

The term microaggression was coined by Chester Pierce, MD, the first Black tenured professor at Massachusetts General Hospital in the 1970’s, to describe the frequent, yet subtle dismissals Black Americans experienced in society. Over time, the term has been expanded to include “brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioral, or environmental indignities, intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative slights and insults” to any marginalized group.5

While the term microaggressions is useful in contextualizing individual experiences, it narrowly focuses on conscious or unconscious interpersonal prejudices. In medicine, this misdirects attention away from the policies and practices that create and reinforce prejudices; these policies and practices do so by systematically excluding underrepresented minority (URM) physicians,6 defined by the American Association of Medical Colleges as physicians who are Black, Hispanic, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives,7 from the medical workforce. Ultimately, this leads to and exacerbates poor health outcomes for racial and ethnic minority patients.

Microaggressions represent our society’s deepest and oldest biases and are rooted in structural racism, as well as misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.8 For URM physicians, experiences like the example above are frequently caused by structural racism.

Structural racism in medicine

Structural racism refers to the policies, practices, cultural representations, and norms that reinforce inequities by providing privileges to White people at the disadvantage of non-White people.9 In 1910, Abraham Flexner, commissioned by the Carnegie Foundation and the American Medical Association, wrote that African American physicians should be trained in hygiene rather than surgery and should primarily serve as “sanitarians” whose purpose was to “protect Whites” from common diseases like tuberculosis.10 The 1910 Flexner Report also emphasized the importance of prerequisite basic sciences education and recommended that only two of the seven existing Black medical schools remain open because Flexner believed that only these schools had the potential to meet the new requirements for medical education.11 A recent analysis found that, had the other five medical schools affiliated with historically Black colleges and universities remained open, this would have resulted in an additional 33,315 Black medical school graduates by 2019.12 Structural racism explains why the majority of practicing physicians, medical educators, National Institutes of Health–funded researchers, and hospital executives are White and, similarly, why White patients are overrepresented in clinical trials, have better health outcomes, and live longer lives than several racial and ethnic minority groups.13

The murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd and the inequitable toll of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black, Hispanic, and Native American people renewed the dialogue regarding structural racism in America. Beyond criminal justice and police reform, the current social justice movement demands that structural racism is examined in all spheres. In medicine and health care, acknowledging the history of exclusion and exploitation of Black people and other URM groups is an important first step, but this must be followed by a commitment to an antiracist future for the benefit of all medical professionals and patients.14,15

Antiracism as a path forward

Antiracism refers to actions and policies that seek to dismantle structural racism. While individuals can and should engage in antiracist actions, it is equally important for organizations and government to actively participate in this process as well.

Individual and interpersonal levels

Gastroenterologists should advocate an end to racist practices within their organizations (e.g., unjustified use of race-based corrections in diagnostic algorithms and practice guidelines),16 and interrupt microaggressions and racist actions in real time (e.g., overpolicing of underrepresented groups in health care settings).17 Gastroenterologists from underrepresented groups may also need to unlearn internalized racism, which is defined as acceptance by members of disadvantaged races of the negative messages about their own abilities and intrinsic worth.18

Organizational level

Gastroenterology divisions and practices must ensure that the entire workforce, including leadership, reflects the diversity of our country. Underrepresented groups represent 33% of the U.S. population, but only 9.1% of gastroenterology fellows and 10% of gastroenterology faculty are from underrepresented groups.19 In addition to diversifying the field of gastroenterology through financial and operational support of pipeline educational programs, organizations should also promote the scholarship of URM groups, whose work is often undervalued, and redistribute power by elevating voices that have been historically absent.20 Gastroenterology practices should also collect high-quality patient data disaggregated by demographic factors. Doing so will enable rapid identification of disparate health outcomes by demographic variables and inform interventions to eliminate identified disparities.

Government level

The “Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government” issued by President Biden on Jan. 20, 2021, is an example of how government can promote antiracism.21 The executive order states that domestic policies cause group inequities and calls for the removal of systemic barriers in current and future domestic policies. The executive order outlines several additional ways to improve equity in current and future policy, including engagement, consultation, and coordination with members of underserved communities. The details outlined in the executive order should serve as the foundation for establishing new standards at the state, county, and city levels as well. Gastroenterologists can influence government by voting for officials at all levels that support and promote these standards.

Conclusion

Beyond calling out microaggressions in real time, we must also interrogate the biases, policies, and practices that support them in medicine and beyond. As Black gastroenterologists who have experienced microaggressions and overt acts of racism, we ground Oviea’s experience in structural racism and offer strategies that individuals, organizations, and governing institutions can adopt toward an antiracist future. This model can be applied to experiences rooted in misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, xenophobia, ableism, and other prejudices.

As a nation, we must make an active and collective choice to address structural racism. In health care, doing so will strengthen communities, enhance the lived experiences of URM physician colleagues, and save patient lives. Gastroenterologists, as trusted health care providers, are uniquely positioned to lead the way.

Dr. Akpotaire is a second-year GI fellow in the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Dr. Issaka is an assistant professor with both the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and the division of gastroenterology at the University of Washington.

References

1. Blackstock U. “Why Black doctors like me are leaving faculty positions in academic medical centers.” STAT News, 2020.

2. Asare JG. “One Doctor Shares Her Story of Racism in Medicine.” Forbes. 2021 Feb 1.

3. Kroman D. “Revered doctor steps down, accusing Seattle Children’s Hospital of racism.” Crosscut. 2020 Dec 31.

4. United States District Court Eastern District of Louisiana. Princess Dennar, M.D. v. The Administrators of the Tulane Educational Fund, 2020.

5. Sue DW. Microaggressions in Everyday Life: Race, Gender, and Sexual Orientation. Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley, 2010.

6. Boyd RW. Lancet. 2019 Jun 22;393(10190):2484-5.

7. AAMC. Diversity in Medicine Facts and Figures 2019. Washington, D.C., 2019.

8. Overland MK et al. PM R. 2019 Sep;11(9):1004-12.

9. Jones CP. Ethn Dis. 2018 Aug 9;28(Suppl 1):231-4.

10. Hlavinka E. “Racial Bias in Flexner Report Permeates Medical Education Today.” Medpage Today. 2020 Jun 18.

11. Flexner A. Medical Education in the United States and Canada. New York: 1910. Republished: Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

12. Campbell KM et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020 Aug 3;3(8):e2015220.

13. Malat J et al. Soc Sci Med. 2018 Feb;199:148-56.

14. Kendi IX. How to be an antiracist. New York: Random House Books, 2019.

15. Gray DM 2nd et al. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Oct;17(10):589-90.

16. Vyas DA et al. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 27;383(9):874-82.

17. Green CR et al. J Natl Med Assoc. 2018 Feb;110(1):37-43.

18. Jones CP. Am J Public Health. 2000 Aug;90(8):1212-5.

19. Anyane-Yeboa A et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Aug;115(8):1147-9.

20. Issaka RB. JAMA. 2020 Aug 11;324(6):556-7.

21. Biden JR. Executive Order On Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government. Washington, D.C.: The White House, 2021.