User login

Abnormal sexual behaviors in frontotemporal dementia

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

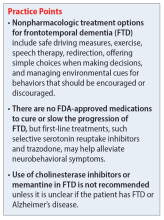

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

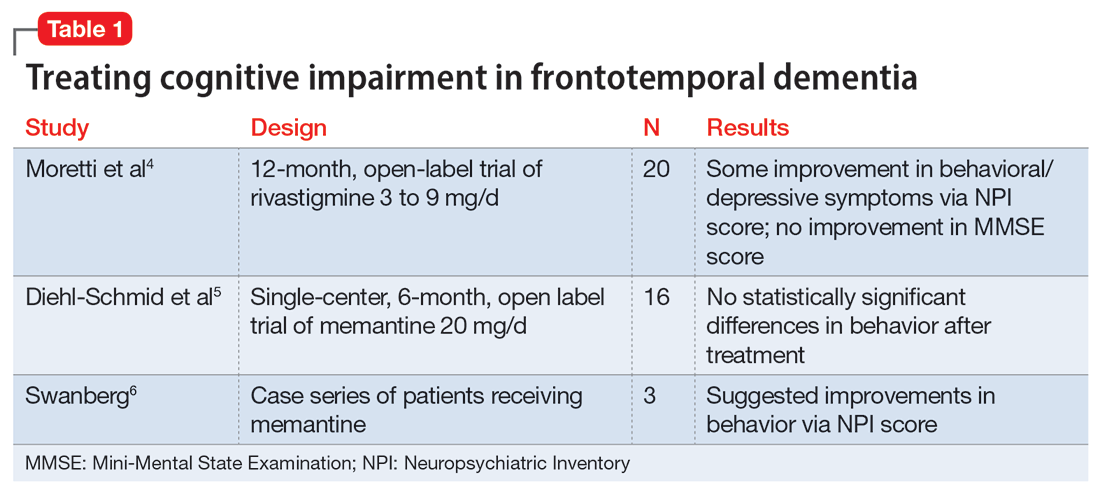

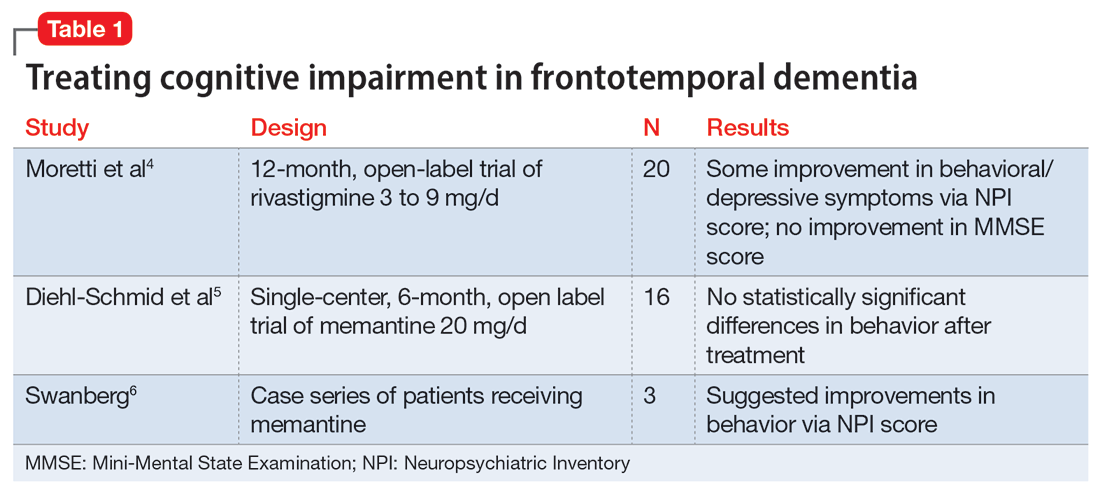

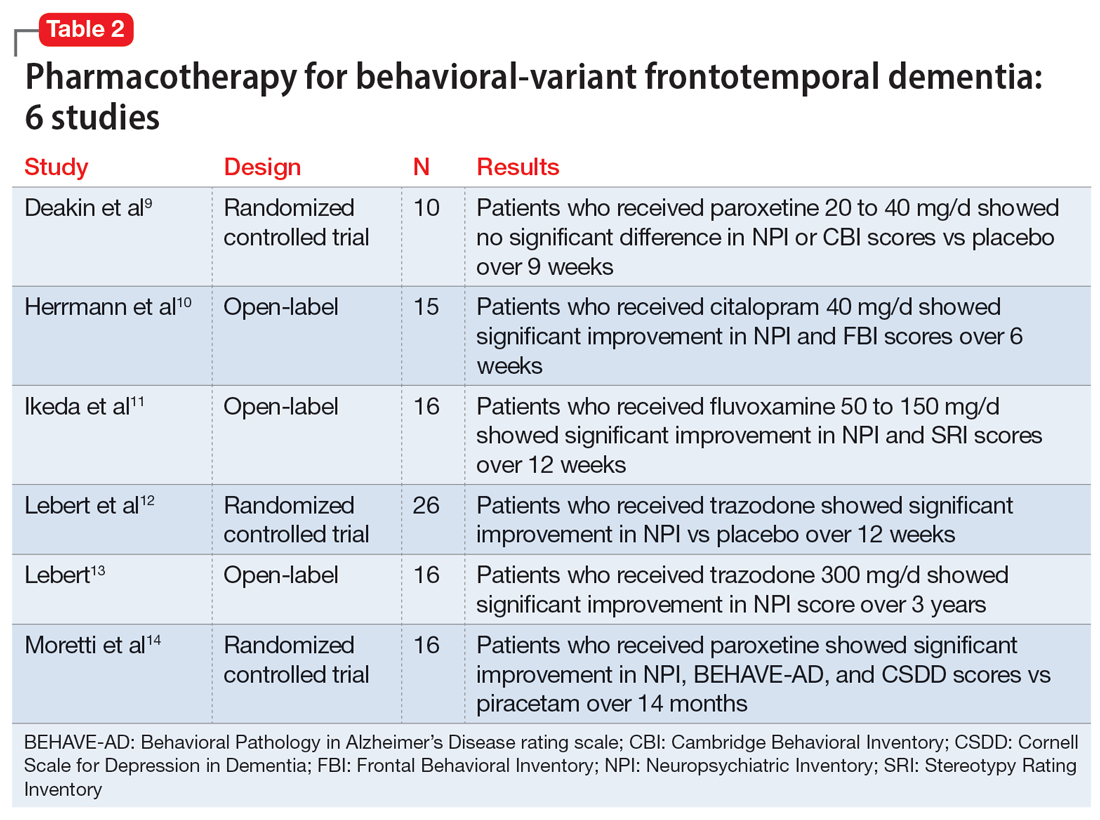

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

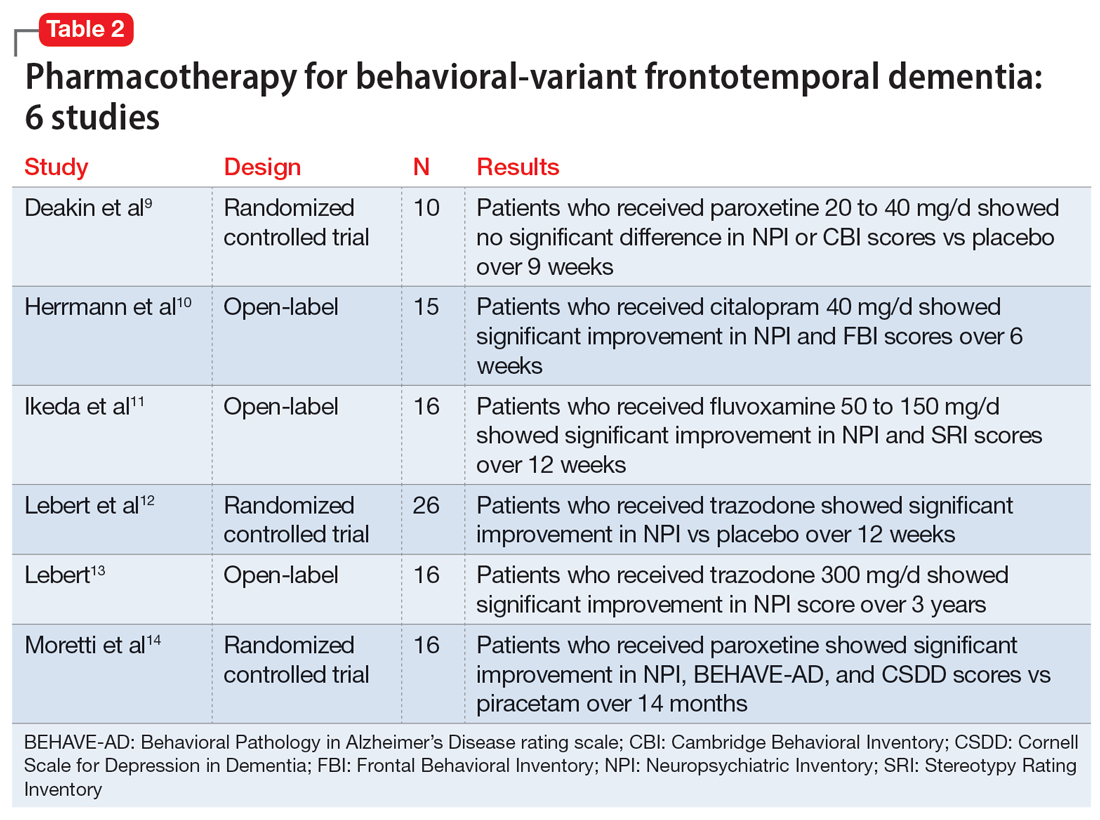

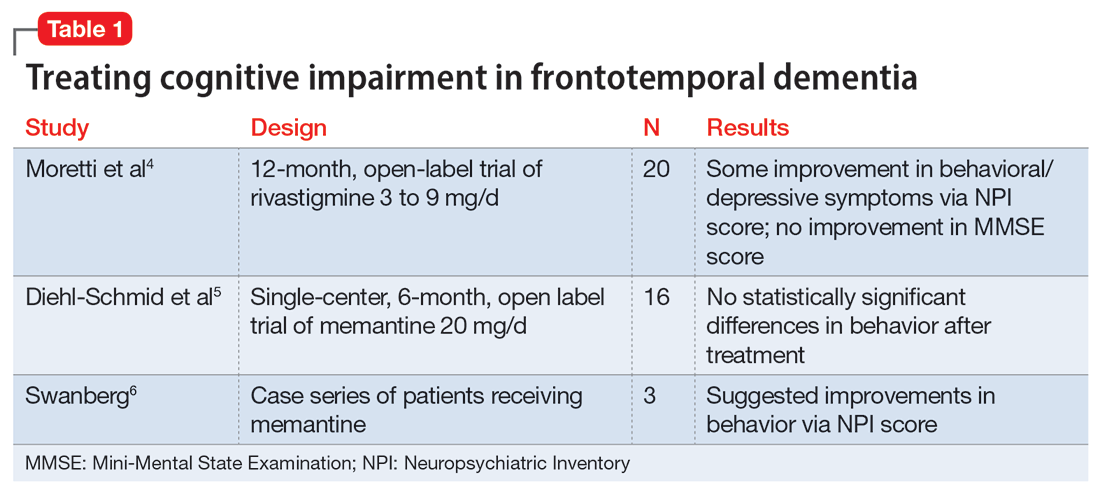

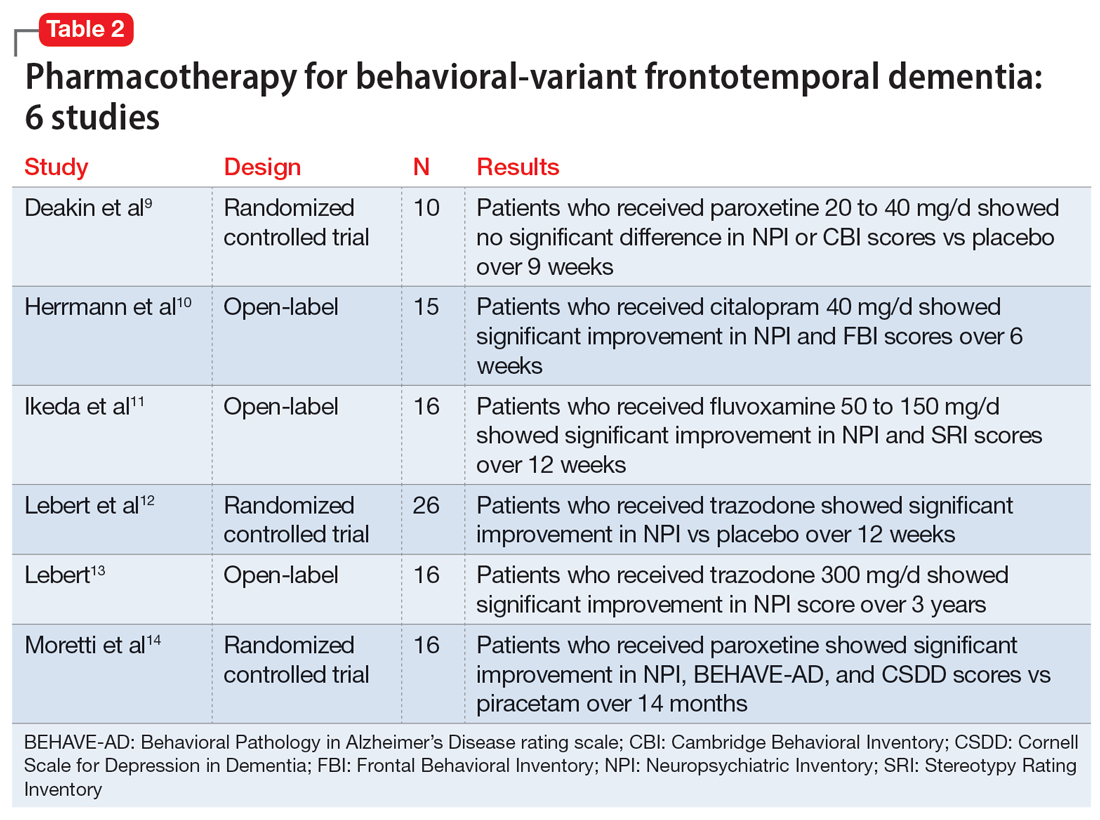

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

Mr. S, age 77, is admitted to a long-term care facility due to progressive cognitive impairment and sexually inappropriate behavior. He has a history of sexual assault of medical staff. His medical history includes significant frontotemporal dementia (FTD) with behavioral disturbances, abnormal sexual behaviors, subclinical hypothyroidism, schizoid personality disorder, Parkinson disease, posttraumatic stress disorder, and hyperammonemia.

Upon admission, Mr. S’s vital signs are within normal limits except for an elevated thyroid-stimulating hormone (4.54 mIU/L; reference range 0.40 to 4.50 mIU/L). Prior cognitive testing results and updated ammonia levels are unavailable. Mr. S’s current medications include acetaminophen 650 mg every 4 hours as needed for pain, calcium carbonate/vitamin D twice daily for bone health, carbidopa/levodopa 25/100 mg twice daily for Parkinson disease, melatonin 3 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia, quetiapine 25 mg twice daily for psychosis with disturbance of behavior and 12.5 mg every 4 hours as needed for agitation, and trazodone 50 mg/d at bedtime for insomnia. Before Mr. S was admitted, previous therapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) had been tapered and discontinued. Mr. S had also started antipsychotic therapy at another facility due to worsening behaviors.

In patients with dementia, the brain is experiencing neurodegeneration. Progressively, neurons may stop functioning, lose connections with other neurons, and ultimately face cell death. The specific dementia diagnosis and its clinical features depend on the type of neurons and region of the brain affected.1,2

FTD occurs in response to damage to the frontal and temporal lobes. The frontal lobe correlates to executive functioning, while the temporal lobe plays a role in speech and comprehension. Damage to these areas may result in loss of movement, trouble speaking, difficulty solving complex problems, and problems with social behavior. Specifically, damage to the orbital frontal cortex may cause disinhibition and abnormal behaviors, including emotional lability, vulgarity, and indifference to social nuances.1 Within an FTD diagnosis, there are 3 disorders: behavioral-variant FTD (bvFTD), semantic dementia, and progressive nonfluent aphasia.1 Specifically, bvFTD can result in abnormal sexual behaviors such as making sexually inappropriate statements, masturbating in public, undressing in public, inappropriately or aggressively touching others, or confusing another individual as an intimate partner. In addition to cognitive impairment, these neurobehavioral symptoms can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life while increasing caregiver burden.2

Occurring at a similar frequency to Alzheimer’s disease in patients age <65, FTD is one of the more common causes of early-onset dementia. The mean age of onset is 58 and onset after age 75 is particularly unusual. Memory may not be affected early in the course of the disease, but social changes are likely. As FTD progresses, symptoms will resemble those of Alzheimer’s disease and patients will require assistance with activities of daily living. In later stages of FTD, patients will exhibit language and behavior symptoms. Due to its unique progression, FTD can be commonly misdiagnosed as other mental illnesses or neurocognitive disorders.1

Approaches to treatment: What to consider

Both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic interventions are appropriate for addressing FTD. Because nonpharmacologic options improve patient safety and overall physical health, they should be used whenever practical. These interventions include safe driving measures, exercise, speech therapy, redirection, offering simple choices when making decisions, and managing environmental cues for behaviors that should be encouraged or discouraged.3

There are no FDA-approved medications to cure or slow the progression of FTD. Therefore, treatment is focused on alleviating neurobehavioral symptoms. The symptoms depend on the type of FTD the patient has; they include cognitive impairment, anxiety, insomnia or sleep disturbances, compulsive behaviors, speech and language problems, and agitation. While many medications have been commonly used for symptomatic relief, evidence for the efficacy of these treatments in FTD is limited.2

Continue to: A review of the literature...

A review of the literature on potential treatments for cognitive impairment and behavioral symptoms of FTD identified 2 trials and 1 case series (Table 14-6) in addition to a 2014 review article7 of current pharmacologic treatments. These trials evaluated cognitive improvement with rivastigmine, memantine, galantamine, and donepezil. None of the trials found a significant benefit from any of these medications for cognitive improvement in FTD. Data were conflicting on whether these medications improved or worsened behavioral symptoms. For example, the case series of 3 patients by Swanberg6 suggested improvement in behavior with memantine, while an open-label study analyzed in a 2014 review article7 found that donepezil may have worsened behaviors. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine in FTD is not recommended unless it is not certain if the patient has FTD or Alzheimer’s disease.7

Addressing sexual behaviors. Creating a treatment regimen for FTD behavioral symptoms—specifically for abnormal sexual behaviors—can be challenging. Before starting pharmacotherapy directed at behavioral symptoms secondary to FTD, other causes of symptoms such as delirium, pain, or discomfort should be excluded. Nonpharmacologic approaches should be aimed at the type of sexual behavior and likely underlying environmental cause. For example, patients may inappropriately disrobe themselves. To address this behavior, hospital staff or caregivers should first eliminate environmental causes by ensuring the room is at a comfortable temperature, dressing the patient in light, breathable clothing, or checking if the patient needs to use the bathroom. If no environmental causes are found, a one-piece jumpsuit with closures on the back of the garment could be utilized to increase the difficulty of undressing.

Other nonpharmacologic methods include providing private areas for patients who are behaving inappropriately or removing potentially stimulating television or media from the environment. Another option is to increase the use of positive, pleasant stimuli. One approach that has shown benefit is music therapy, utilizing popular music genres from the patient’s youth.3

Evidence for pharmacotherapy is limited and largely from case reports and case series. A 2020 meta-analysis by Trieu et al8 reviewed 23 studies to expand on current clinical guidance for patients with bvFTD. These studies showed improvements in behavioral symptoms and reductions in caregiver fatigue with citalopram, trazodone, paroxetine, and fluvoxamine. Six of the trials included in this meta-analysis that evaluated these 4 medications are summarized in Table 2.9-14

Due to the lower risk of adverse effects and favorable safety profiles, SSRIs and trazodone are considered first-line treatment options. Benefit from these medications is theorized to be a result of their serotonergic effects, because serotonin abnormalities and dysfunction have been linked to FTD symptoms. For example, in a patient experiencing hypersexuality, the common adverse effect of low libido associated with SSRIs can be particularly beneficial.8

Continue to: Other medication classes studied in patients...

Other medication classes studied in patients with FTD include antipsychotics, stimulants, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines, and hormonal therapies. In addition to a black box warning for increased mortality in older patients with dementia-related psychosis, antipsychotics are associated with other serious adverse effects and should be used with caution.7

FTD is a debilitating disease that has a major impact on quality of life, particularly when behavioral symptoms accompany cognitive decline. Though some therapies may possibly improve behavioral symptoms, their routine use remains controversial due to a lack of clear evidence of benefit. In caring for patients with FTD and behavioral symptoms, a multimodal, team-based approach is vital.1

CASE CONTINUED

The treatment team starts Mr. S on several of the modalities discussed in this article over the span of 2 years, with limited efficacy. Nonpharmacologic methods do not provide much benefit because Mr. S is extremely difficult to redirect. Given Mr. S’s past trials of SSRIs prior to admission, sertraline was retrialed and titrated over 2 years. The highest dose utilized during his admission was 200 mg/d. The team starts estrogen therapy but tapers and discontinues it due to ineffectiveness. Mr. S’s use of carbidopa/levodopa is thought to be contributing to his behavioral abnormalities, so the team tapers it to discontinuation; however, Mr. S’s sexually inappropriate behaviors and agitation continue. The team initiates a plan to reduce the dose of quetiapine and switch to gabapentin, but Mr. S fails gradual dose reduction due to his worsening behaviors. He starts gabapentin. The team gradually increases the dose of gabapentin to decrease libido and agitation, respectively. The increase in sertraline dose and use of nonpharmacologic modalities causes Mr. S’s use of as-needed antipsychotics to decrease.

Related Resources

- Ellison JM. What are the stages of frontotemporal dementia? BrightFocus Foundation. July 5, 2021. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://www.brightfocus.org/alzheimers/article/what-are-stages-frontotemporal-dementia

- Dementia and sexually inappropriate behavior. ReaDementia. January 31, 2022. Accessed July 7, 2023. https://readementia.com/dementia-and-sexually-inappropriate-behavior/

Drug Brand Names

Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

Citalopram • Celexa

Donepezil • Aricept

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Galantamine • Razadyne

Memantine • Namenda

Paroxetine • Paxil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Sertraline • Zoloft

Trazodone • Desyrel

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021

1. Grossman M. Frontotemporal dementia: a review. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2002;8(4):566-583. doi:10.1017/s1355617702814357

2. The Johns Hopkins University. Frontotemporal dementia. Johns Hopkins Medicine. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/health/conditions-and-diseases/dementia/frontotemporal-dementia

3. Shinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283-293. doi:10.3233/JAD-142109

4. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Rivastigmine in frontotemporal dementia: an open-label study. Drugs Aging. 2004;21(14):931-937. doi:10.2165/00002512-200421140-00003

5. Diehl-Schmid J, Förstl H, Perneczky R, et al. A 6-month, open-label study for memantine in patients with frontotemporal dementia. In J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(7):754-759. doi:10.1002/gps.1973

6. Swanberg MM. Memantine for behavioral disturbances in frontotemporal dementia: a case series. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(2):164-166. doi:10.1097/WAD.0b013e318047df5d

7. Tsai RM, Boxer AL. Treatment of frontotemporal dementia. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2014;16(11):319. doi:10.1007/s11940-014-0319-0

8. Trieu C, Gossink F, Stek ML, et al. Effectiveness of pharmacological interventions for symptoms of behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2020;33(1):1-15. doi:10.1097/WNN.0000000000000217

9. Deakin JB, Rahman S, Nestor PJ, et al. Paroxetine does not improve symptoms and impairs cognition in frontotemporal dementia: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;172(4):400-408. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1686-5

10. Herrmann N, Black SE, Chow T, et al. Serotonergic function and treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of frontotemporal dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(9):789-797. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31823033f3

11. Ikeda M, Shigenobu K, Fukuhara R, et al. Efficacy of fluvoxamine as a treatment for behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration patients. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(3):117-121. doi:10.1159/000076343

12. Lebert F, Stekke W, Hasenbroekx C, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: a randomised, controlled trial with trazodone. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17(4):355-359. doi:10.1159/000077171

13. Lebert F. Behavioral benefits of trazodone are sustained for the long term in frontotemporal dementia. Therapy. 2006;3(1):93-96. doi:10.1586/14750708.3.1.93

14. Moretti R, Torre P, Antonello RM, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: paroxetine as a possible treatment of behavior symptoms. A randomized, controlled, open 14-month study. Eur Neurol. 2003;49(1):13-19. doi:10.1159/000067021