User login

Managing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

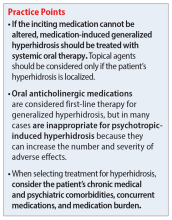

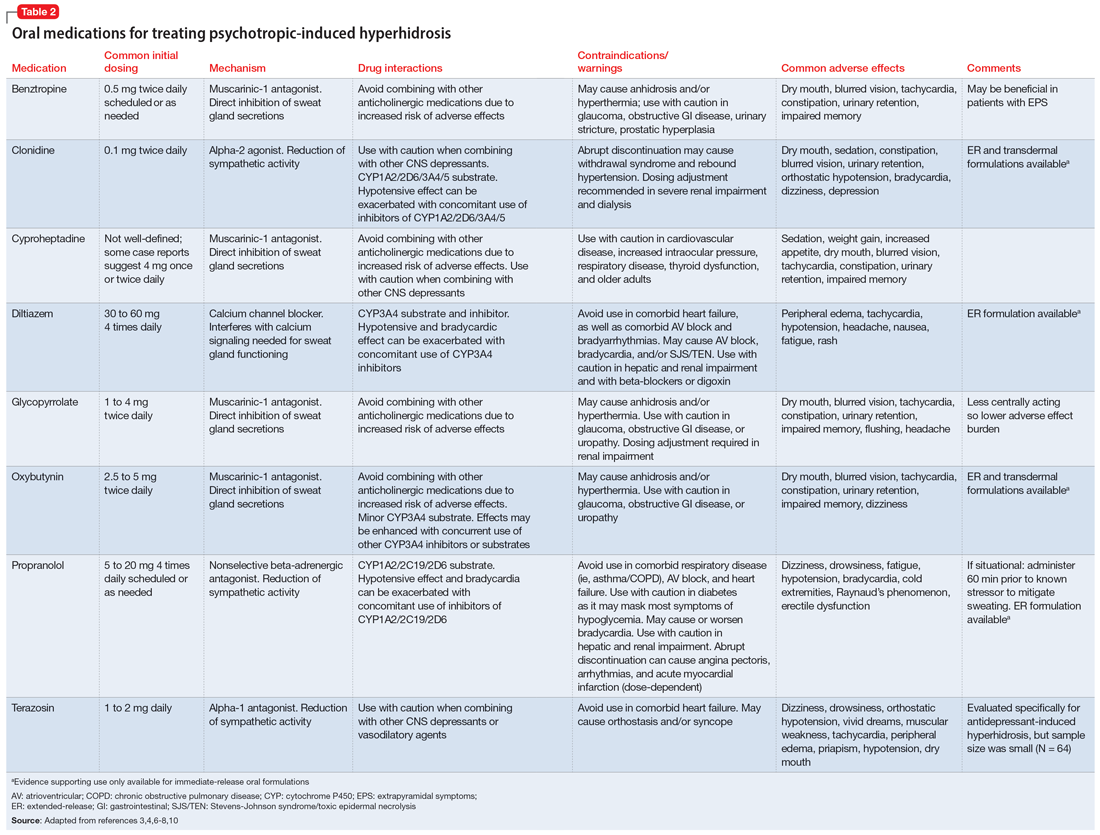

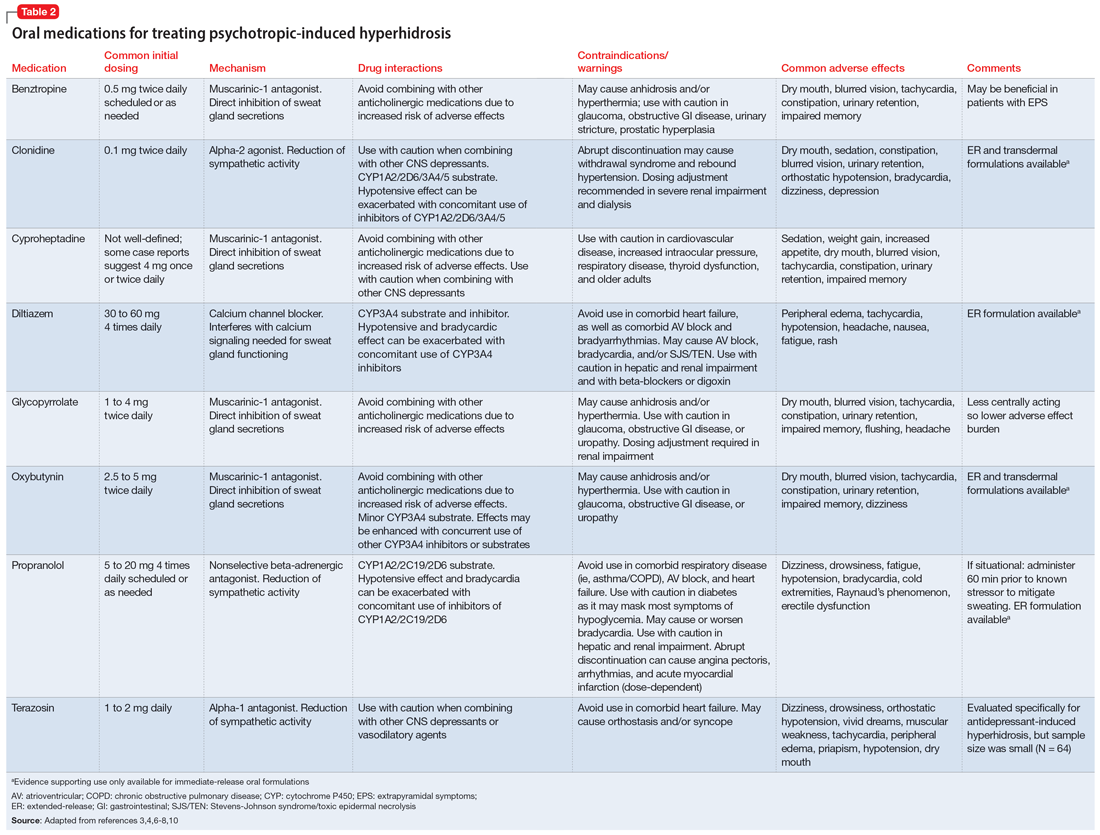

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

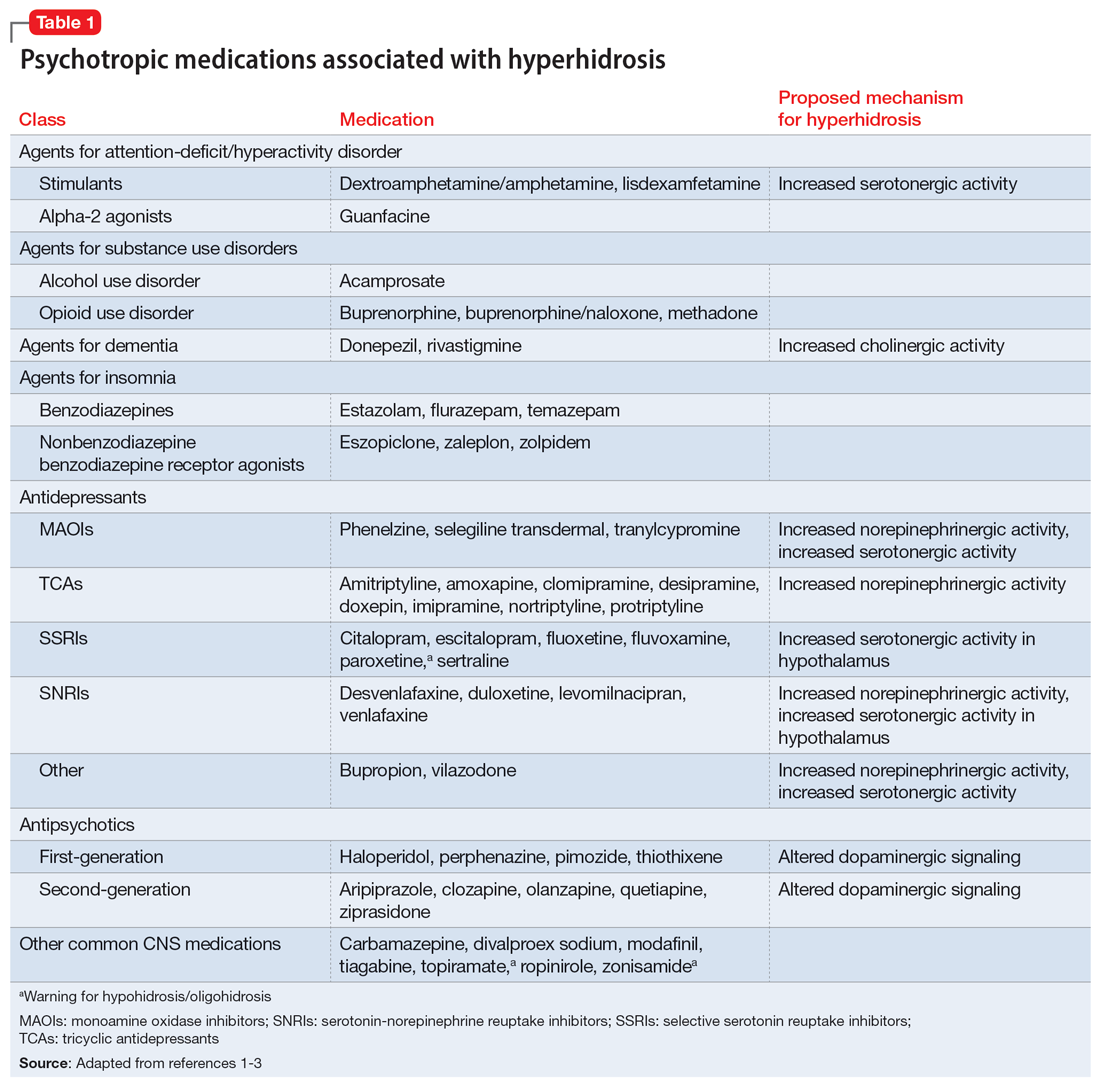

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

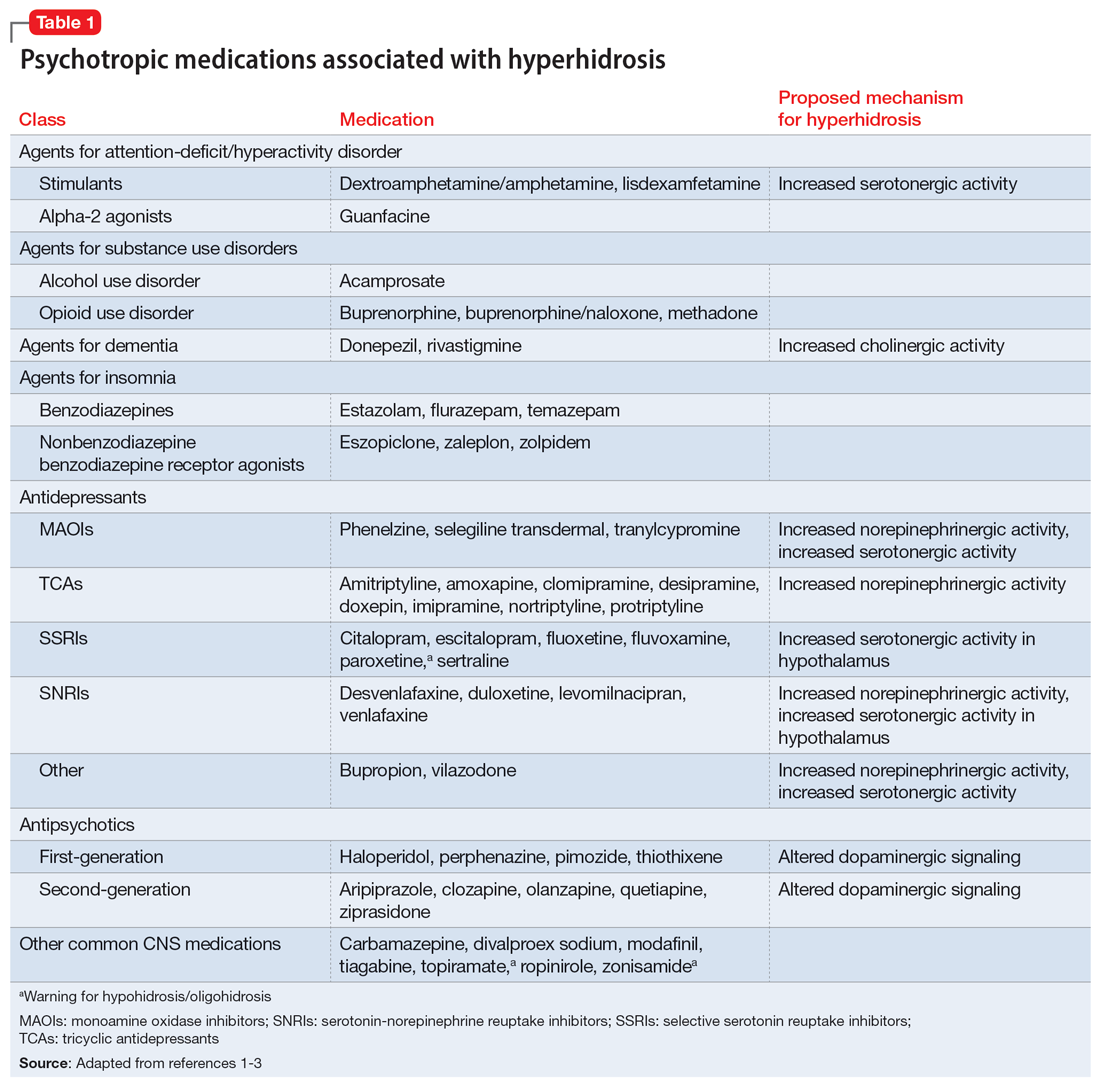

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

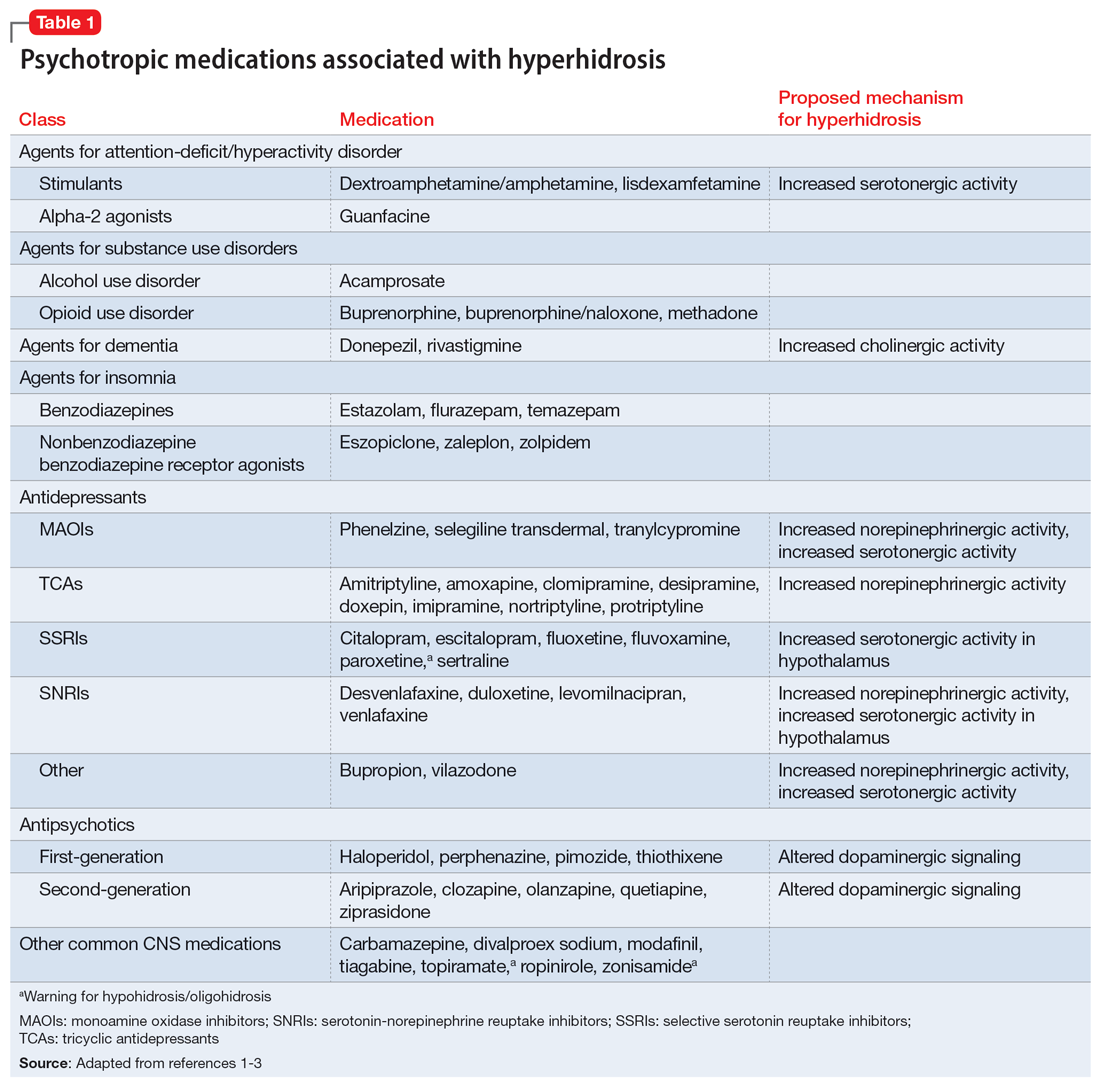

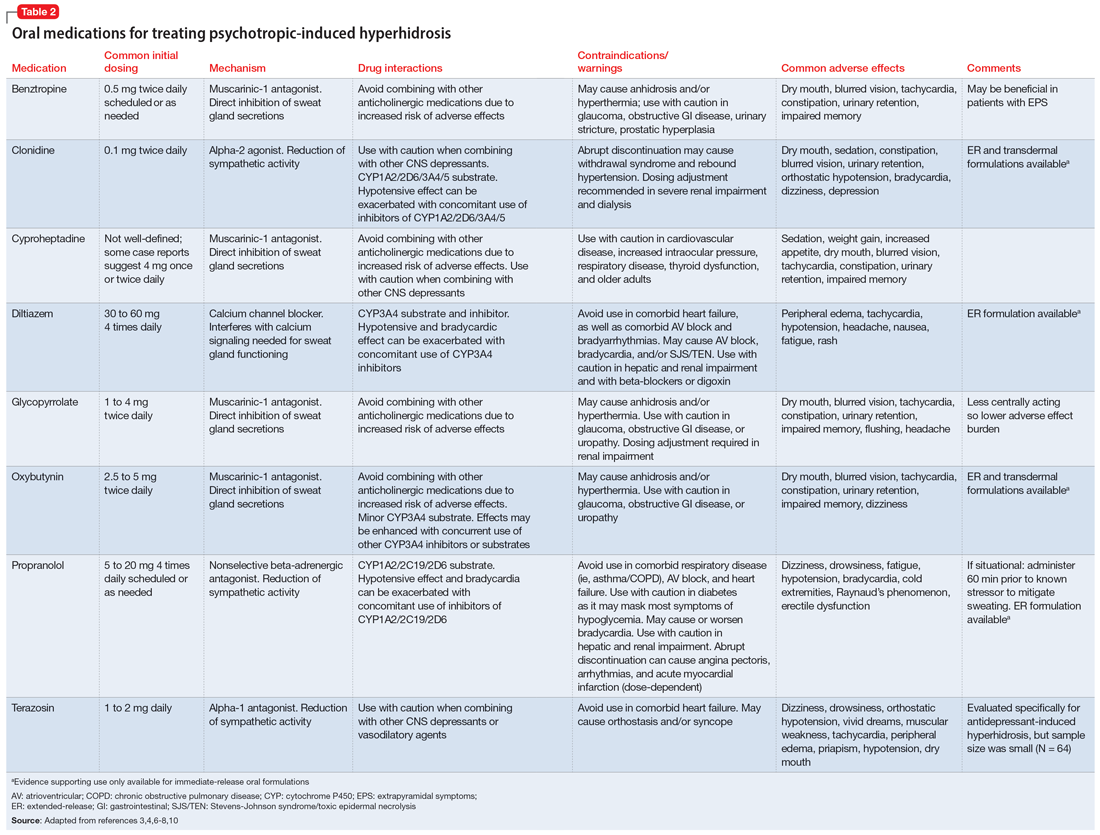

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

Ms. K, age 32, presents to the psychiatric clinic for a routine follow-up. Her history includes agoraphobia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and schizoaffective disorder. Ms. K’s current medications are oral hydroxyzine 50 mg 4 times daily as needed for anxiety and paliperidone palmitate 234 mg IM monthly. Since her last follow-up, she has been switched from oral sertraline 150 mg/d to oral paroxetine 20 mg/d. Ms. K reports having constipation (which improves by taking oral docusate 100 mg twice daily) and generalized hyperhidrosis. She wants to alleviate the hyperhidrosis without changing her paroxetine because that medication improved her symptoms.

Hyperhidrosis—excessive sweating not needed to maintain a normal body temperature—is an uncommon and uncomfortable adverse effect of many medications, including psychotropics.1 This long-term adverse effect typically is not dose-related and does not remit with continued therapy.2Table 11-3 lists psychotropic medications associated with hyperhidrosis as well as postulated mechanisms.

The incidence of medication-induced hyperhidrosis is unknown,but for psychotropic medications it is estimated to be 5% to 20%.3 Patients may not report hyperhidrosis due to embarrassment; in clinical trials, reporting measures may be inconsistent and, in some cases, misleading. For example, it is possible hyperhidrosis that appears to be associated with buprenorphine is actually a symptom of the withdrawal syndrome rather than a direct effect of the medication. Also, some medications, including certain psychotropics (eg, paroxetine4 and topiramate3) may cause either hyperhidrosis or hypohidrosis (decreased sweating). Few medications carry labeled warnings for hypohidrosis; the condition generally is not of clinical concern unless patients experience heat intolerance or hyperthermia.3

Psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis is likely an idiopathic effect. There are few known predisposing factors, but some medications carry a greater risk than others. In a meta-analysis, Beyer et al2 found certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, had a higher risk of causing hyperhidrosis. Fluvoxamine, bupropion, and vortioxetine had the lowest risk. The class risk for SSRIs was comparable to that of serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which all carried a comparable risk. In this analysis, neither indication nor dose were reliable indicators of risk of causing hyperhidrosis. However, the study found that for both SSRIs and SNRIs, increased affinity for the dopamine transporter was correlated with an increased risk of hyperhidrosis.2

Treatment

Treatment of hyperhidrosis depends on its cause and presentation.5 Hyperhidrosis may be categorized as primary (idiopathic) or secondary (also termed diaphoresis), and either focal or generalized.6 Many treatment recommendations focus on primary or focal hyperhidrosis and prioritize topical therapies.5 Because medication-induced hyperhidrosis most commonly presents as generalized3 and thus affects a large body surface area, the use of topical therapies is precluded. Topical therapy for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be pursued only if the patient’s sweating is localized.

Treating medication-induced hyperhidrosis becomes more complicated if it is not possible to alter the inciting medication (ie, because the medication is effective or the patient is resistant to change). In such scenarios, discontinuing the medication and initiating an alternative therapy may not be effective or feasible.2 For generalized presentations of medication-induced hyperhidrosis, if the inciting medication cannot be altered, initiating an oral systemic therapy is the preferred treatment.3,5

Oral anticholinergic medications (eg, benztropine, glycopyrrolate, and oxybutynin),4-6 act directly on muscarinic receptors within the eccrine sweat glands to decrease or stop sweating. They are considered first-line for generalized hyperhidrosis but may be inappropriate for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis because many psychotropics (eg, tricyclic antidepressants, paroxetine, olanzapine, quetiapine, and clozapine) have anticholinergic properties. Adding an anticholinergic medication to these patients’ regimens may increase the adverse effect burden and worsen cognitive deficits. Additionally, approximately one-third of patients discontinue anticholinergic medications due to tolerability issues (eg, dry mouth).

Continue to: However, anticholinergic medications...

However, anticholinergic medications may still have a role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis. Benztropine3,7,8 and cyproheptadine2,3,9 may be effective options, though their role in treating psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis should be limited and reserved for patients who have another compelling indication for these medications (eg, extrapyramidal symptoms) or when other treatment options are ineffective or intolerable.

Avoiding anticholinergic medications can also be justified based on the proposed mechanism of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as an extension of the medication’s toxic effects. Conceptualizing psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis as similar to the diaphoresis and hyperthermia observed in neuroleptic malignant syndrome and serotonin syndrome offers a clearer target for treatment. Though the specifics of the mechanisms remain unknown,2 many medications that cause hyperhidrosis do so by increasing sweat gland secretions, either directly by increasing cholinergic activity or indirectly via increased sympathetic transmission.

Considering this pathophysiology, another target for psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis may be altered and/or excessive catecholamine activity. The use of medications such as clonidine,3-6 propranolol,4-6 or terazosin2,3,10 should be considered given their beneficial effects on the activation of the sympathetic nervous system, although clonidine also possesses anticholinergic activity. The calcium channel blocker diltiazem can improve hyperhidrosis symptoms by interfering with the calcium signaling necessary for normal sweat gland function.4,5 Comorbid cardiovascular diseases and tachycardia, an adverse effect of many psychotropic medications, may also be managed with these treatment options. Some research suggests using benzodiazepines to treat psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis.4-6 As is the case for anticholinergic medications, the use of benzodiazepines would require another compelling indication for long-term use.

Table 23,4,6-8,10 provides recommended dosing and caveats for the use of these medications and other potentially appropriate medications.

Research of investigational treatments for generalized hyperhidrosis is ongoing. It is possible some of these medications may have a future role in the treatment of psychotropic-induced hyperhidrosis, with improved efficacy and better tolerability.

Continue to: CASE CONTINUED

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. K’s medication-induced hyperhidrosis is generalized and therefore ineligible for topical therapies, and because the inciting medication (paroxetine) cannot be switched to an alternative, the treatment team considers adding an oral medication. Treatment with an anticholinergic medication, such as benztropine, is not preferred due to the anticholinergic activity associated with paroxetine and Ms. K’s history of constipation. After discussing other oral treatment options with Ms. K, the team ultimately decides to initiate propranolol at a low dose (5 mg twice daily) to minimize the chances of an interaction with paroxetine, and titrate based on efficacy and tolerability.

Related Resources

- International Hyperhidrosis Society. Hyperhidrosis treatment overview. www.sweathelp.org/hyperhidrosis-treatments/treatment-overview.html

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Buprenorphine • Sublocade

Buprenorphine/naloxone • Zubsolv

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Tegretol

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Clonidine • Catapres

Clozapine • Clozaril

Desipramine • Norpramin

Desvenlafaxine • Pristiq

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine • Adderall

Diltiazem • Cardizem

Divalproex • Depakote

Donepezil • Aricept

Doxepin • Silenor

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Eszopiclone • Lunesta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Guanfacine • Intuniv

Glycopyrrolate • Cuvposa

Hydroxyzine • Vistaril

Imipramine • Tofranil

Levomilnacipran • Fetzima

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methadone • Dolophine, Methadose

Modafinil • Provigil

Nortriptyline • Pamelor

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Paliperidone palmitate • Invega Sustenna

Paroxetine • Paxil

Phenelzine • Nardil

Pimozide • Orap

Protriptyline • Vivactil

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Rivastigmine • Exelon

Selegiline transdermal • Emsam

Sertraline • Zoloft

Temazepam • Restoril

Thiothixene • Navane

Tiagabine • Gabitril

Topiramate • Topamax

Tranylcypromine • Parnate

Vilazodone • Viibryd

Vortioxetine • Trintellix

Zaleplon • Sonata

Ziprasidone • Geodon

Zolpidem • Ambien

Zonisamide • Zonegran

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449

1. International Hyperhidrosis Society. Drugs/medications known to cause hyperhidrosis. Sweathelp.org. 2022. Accessed September 6, 2022. https://www.sweathelp.org/pdf/drugs_2009.pdf

2. Beyer C, Cappetta K, Johnson JA, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of hyperhidrosis with second-generation antidepressants. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(12):1134-1146. doi:10.1002/da.22680

3. Cheshire WP, Fealey RD. Drug-induced hyperhidrosis and hypohidrosis: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf. 2008;31(2):109-126. doi:10.2165/00002018-200831020-00002

4. del Boz J. Systemic treatment of hyperhidrosis. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2015;106(4):271-277. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2014.11.012

5. Nawrocki S, Cha J. The etiology, diagnosis, and management of hyperhidrosis: a comprehensive review: therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81(3):669-680. doi:10.1016/j.jaad2018.11.066

6. Glaser DA. Oral medications. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32(4):527-532. doi:10.1016/j.det.2014.06.002

7. Garber A, Gregory RJ. Benztropine in the treatment of venlafaxine-induced sweating. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(4):176-177. doi:10.4088/jcp.v58n0407e

8. Kolli V, Ramaswamy S. Improvement of antidepressant-induced sweating with as-required benztropine. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(11-12):10-11.

9. Ashton AK, Weinstein WL. Cyproheptadine for drug-induced sweating. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(5):875. doi:10.1176/APPI.AJP.159.5.874-A

10. Ghaleiha A, Shahidi KM, Afzali S, et al. Effect of terazosin on sweating in patients with major depressive disorder receiving sertraline: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2013;17(1):44-47. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.687449