User login

Addressing the Shortage of Physician Assistants in Medicine Clerkship Sites

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

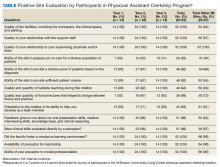

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

The Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics projects 37% job growth for physician assistants (PAs) from 2016 to 2026, much greater than the average for all other occupations as well as for other medical professions.1 This growth has been accompanied by increased enrollment in medical (doctor of medicine [MD], doctor of osteopathic medicine) and nurse practitioner (NP) schools.2 Clinical teaching sites serve a crucial function in the training of all clinical disciplines. These sites provide hands-on and experiential learning in medical settings, necessary components for learners practicing to become clinicians. Significant PA program expansion has led to increased demand for clinical training, creating competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors.3

This challenge has been recognized by PA program directors. In the Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey, PA program directors expressed concern about the adequacy of clinical opportunities for students, increased difficulty developing new core sites, and preserving existing core sites. In addition, they noted that a shortage of clinical sites was one of the greatest barriers to the PA programs’ sustained growth and success.4

Program directors also indicated difficulty securing clinical training sites in internal medicine (IM) and high rates of attrition of medicine clinical preceptors for their students.5 The reasons are multifold: increasing clinical demands, time, teaching competence, lack of experience, academic affiliation, lack of reimbursement, or compensation. Moreover, there is a declining number of PAs who work in primary care compared with specialty and subspecialty care, limiting the availability of clinical training preceptors in medicine and primary care.6-8 According to the American Academy of PAs (AAPA) census and salary survey data, the percentage of PAs working in the primary care specialties (ie, family medicine, IM, and general pediatrics) has decreased from > 47% in 1995 to 24% in 2017.9 As such, there is a need to broaden the educational landscape to provide more high-quality training sites in IM.

The postacute health care setting may address this training need. It offers a unique clinical opportunity to expose learners to a broad range of disease complexity and clinical acuity, as the percentage of patients discharged from hospitals to postacute care (PAC) has increased and care shifts from the hospital to the PAC setting.10,11 The longer PAC length of stay also enables learners to follow patients longitudinally over several weeks and experience interprofessional team-based care. In addition, the PAC setting offers learners the ability to acquire the necessary skills for smooth and effective transitions of care. This setting has been extensively used for trainees of nursing, pharmacy, physical therapy (PT) and occupational therapy (OT), speech-language pathology, psychology, and social work (SW), but few programs have used the PAC setting as clerkship sites for IM rotations for PA students. To address this need for IM sites, the VA Boston Healthcare System (VABHS), in conjunction with the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program, developed a novel medicine clinical clerkship site for physician assistants in the PAC unit of the community living center (CLC) at VABHS. This report describes the program structure, curriculum, and participant evaluation results.

Clinical Clerkship Program

VABHS CLC is a 110-bed facility comprising 3 units: a 65-bed PAC unit, a 15-bed closed hospice/palliative care unit, and a 30-bed long-term care unit. The service is staffed continuously with physicians, PAs, and NPs. A majority of patients are admitted from the acute care hospital of VABHS (West Roxbury campus) and other regional VA facilities. The CLC offers dynamic services, including phlebotomy, general radiology, IV diuretics and antibiotics, wound care, and subacute PT, OT, and speech-language pathology rehabilitation. The CLC serves as a venue for transitioning patients from acute inpatient care to home. The patient population is often elderly, with multiple active comorbidities and variable medical literacy, adherence, and follow-up.

The CLC provides a diverse interprofessional learning environment, offering core IM rotations for first-year psychiatry residents, oral and maxillofacial surgery residents, and PA students. The CLC also has expanded as a clinical site both for transitions-in-care IM resident curricula and electives as well as a geriatrics fellowship. In addition, the site offers rotations for NPs, nursing, pharmacy, physical and occupational therapies, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW.

The Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program was founded in 2015 as a master’s degree program completed over 28 months. The first 12 months are didactic, and the following 16 months are clinical training with 14 months of rotations (2 IM, family medicine, pediatrics, emergency medicine, general surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, psychiatry, neurology, and 5 elective rotations), and 2 months for a thesis. The program has about 30 students per year and 4 clerkship sites for IM.

Program Description

The VABHS medicine clerkship hosts 1 to 2 PA students for 4-week blocks in the PAC unit of the CLC. Each student rotates on both PA and MD teams. Students follow 3 to 4 patients and participate fully in their care from admission to discharge; they prepare daily presentations and participate in medical management, family meetings, chart documentation, and care coordination with the interprofessional team. Students are provided a physical examination checklist and feedback form, and they are expected to track findings and record feedback and goals with their supervising preceptor weekly. They also make formal case presentations and participate in monthly medicine didactic rounds available to all VABHS IM students and trainees via videoconference.

In addition, beginning in July 2017, all PA students in the CLC began to participate in a 4-week Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care. The curriculum includes 14 didactic lectures taught by 16 interprofessional faculty, including medicine, geriatric, and palliative care physicians; PAs; social workers; physical and occupational therapists; pharmacists; and a geriatric psychologist. The didactics include topics on the interprofessional team, the care continuum, teams and teamwork, interdisciplinary coordination of care, components of effective transitions in care, medication reconciliation, approaching difficult conversations, advance care planning, and quality improvement. The goal of the curriculum is to provide learners the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary for high-quality transitional care and interprofessional practice as well as specific training for effective and safe transfers of care between clinical settings. Although PA students are the main participants in this curriculum, all other learners in the PAC unit are also invited to attend the lectures.

The unique attributes of this training site include direct interaction with supervising PAs and physicians, rather than experiencing the traditional teaching hierarchy (with interns, residents, fellows); observation of the natural progression of disease of both acute care and primary care issues due to the longer length of stay (2 to 6 weeks, where the typical student will see the same patient 7 to 10 times during their rotation); exposure to a host of medically complex patients offering a multitude of clinical scenarios and abnormal physical exam findings; exposure to a hospice/palliative care ward and end-of-life care; and interaction within an interprofessional training environment of nursing, pharmacy, PT, OT, speech-language pathology, psychology, and SW trainees.

Program Evaluation

At the end of rotations continuously through the year, PA students electronically complete a site evaluation from the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program. The evaluation consists of 14 questions: 6 about site quality and 8 about instruction quality. The questions are answered on a 5-point Likert scale. Also included are 2 open-ended response questions that ask what they liked about the rotation and what they felt could be improved. Results are anonymous, de-identified and blinded both to the program as well as the clerkship site. Results are aggregated and provided to program sites annually. Responses are converted to a dichotomous variable, where any good or excellent response (4 or 5) is considered positive and any neutral or below (3, 2, 1) is considered a nonpositive response.

Results

The clerkship site has been operational since June 22, 2015. There have been 59 students who participated in the rotation. A different scale in these evaluations was used between June 22, 2015, and September 13, 2015. Therefore, 7 responses were excluded from the analysis, leaving 52 usable evaluations. The responses were analyzed both in total (for the CLC as well as other IM rotation sites) and by individual clerkship year to look for any trends over time: September 14, 2015, through April 24, 2016; April 25, 2016, through April 28, 2017; and May 1, 2017, through March 1, 2018 (Table).

Site evaluations showed high satisfaction regarding the quality of the physical environment as well as the learning environment. Students endorsed the PAC unit having resources and physical space for them, such as a desk and computer, opportunity for participation in patient care, and parking (100%; n = 52). Site evaluations revealed high satisfaction with the quality of teaching and faculty encouragement and support of their learning (100%; n = 52). The evaluations revealed that bedside teaching was strong (94%; n = 49). The students reported high satisfaction with the volume of patients provided (92%; n = 48) as well as the diversity of diagnoses (92%; n = 48).

There were fewer positive responses in the first 2 years of the rotation with regard to formal lectures (50% and 67%; 7/14 and 16/24, respectively). In the third year of the rotation, students had a much higher satisfaction rate (93%; 13/14). This increased satisfaction was associated with the development and incorporation of the Interprofessional Curriculum in Transitional Care in 2017.

Discussion

Access to high-quality PA student clerkship sites has become a pressing issue in recent years because of increased competition for sites and a shortage of willing and well-trained preceptors. There has been marked growth in schools and enrollment across all medical professions. The Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the PA (ARC-PA) reported that the total number of accredited entry-level PA programs in 2018 was 246, with 58 new accredited programs projected by 2022.12 The Joint Report of the 2013 Multi-Discipline Clerkship/Clinical Training Site Survey reported a 66% increase in first-year enrollment in PA programs from 2002 to 2012.5 Programs must implement alternative strategies to attract clinical sites (eg, academic appointments, increased clinical resources to training sites) or face continued challenges with recruiting training sites for their students. Postacute care may be a natural extension to expand the footprint for clinical sites for these programs, augmenting acute inpatient and outpatient rotations. This implementation would increase the pool of clinical training sites and preceptors.

The experience with this novel training site, based on PA student feedback and evaluations, has been positive, and the postacute setting can provide students with high-quality IM clinical experiences. Students report adequate patient volume and diversity. In addition, evaluations are comparable with that of other IM site rotations the students experience. Qualitative feedback has emphasized the value of following patients over longer periods; eg, weeks vs days (as in acute care) enabling students to build relationships with patients as well as observe a richer clinical spectrum of disease over a less compressed period. “Patients have complex issues, so from a medical standpoint it challenges you to think of new ways to manage their care,” commented a representative student. “It is really beneficial that you can follow them over time.”

Furthermore, in response to student feedback on didactics, an interprofessional curriculum was developed to add formal structure as well as to create a curriculum in care transitions. This curriculum provided a unique opportunity for PA students to receive formal instruction on areas of particular relevance for transitional care (eg, care continuum, end of life issues, and care transitions). The curriculum also allows the interprofessional faculty a unique and enjoyable opportunity for interprofessional collaboration.

The 1 month PAC rotation is augmented with inpatient IM and outpatient family medicine rotations, consequently giving exposure to the full continuum of care. The PAC setting provides learners multifaceted benefits: the opportunity to strengthen and develop the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary for IM; increased understanding of other professions by observing and interacting as a team caring for a patient over a longer period as opposed to the acute care setting; the ability to perform effective, efficient, and safe transfer between clinical settings; and broad exposure to transitional care. As a result, the PAC rotation enhances but does not replace the necessary and essential rotations of inpatient and outpatient medicine.

Moreover, this rotation provides unique and core IM training for PA students. Our site focuses on interprofessional collaboration, emphasizing the importance of team-based care, an essential concept in modern day medicine. Formal exposure to other care specialties, such as PT and OT, SW, and mental health, is essential for students to appreciate clinical medicine and a patient’s physical and mental experience over the course of a disease and clinical state. In addition, the physical exam checklist ensures that students are exposed to the full spectrum of IM examination findings during their rotation. Finally, weekly feedback forms require students to ask and receive concrete feedback from their supervising providers.

Limitations

The generalizability of this model requires careful consideration. VABHS is a tertiary care integrated health care system, enabling students to learn from patients moving through multiple care transitions in a single health care system. In addition, other settings may not have the staffing or clinical volume to sustain such a model. All PAC clinical faculty teach voluntarily, and local leadership has set expectations for all clinicians to participate in teaching of trainees and PA students. Evaluations also note less diversity in the patient population, a challenge that some VA facilities face. This issue could be addressed by ensuring that students also have IM rotations at other inpatient medical facilities. A more balanced experience, where students reap the positive benefits of PAC but do not lose exposure to a diverse patient pool, could result. Furthermore, some of the perceived positive impacts also may be related to professional and personal attributes of the teaching clinicians rather than to the PAC setting.

Conclusion

PAC settings can be effective training sites for medicine clerkships for PA students and can provide high-quality training in IM as PA programs continue to expand. This setting offers students exposure to interprofessional, team-based care and the opportunity to care for patients with a broad range of disease complexity. Learning is further enhanced by the ability to follow patients longitudinally over their disease course as well as to work directly with teaching faculty and other interprofessional health care professionals. Evaluations of this novel clerkship experience have shown high levels of student satisfaction in knowledge growth, clinical skills, bedside teaching, and mentorship.

Acknowledgments

We thank Juman Hijab for her critical role in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank Steven Simon, Matt Russell, and Thomas Parrino for their leadership and guidance in establishing and maintaining the clerkship. We thank the Boston University School of Medicine Physician Assistant Program Director Mary Warner for her support and guidance in creating and supporting the clerkship. In addition, we thank the interprofessional education faculty for their dedicated involvement in teaching, including Stephanie Saunders, Lindsay Lefers, Jessica Rawlins, Lindsay Brennan, Angela Viani, Eric Charette, Nicole O’Neil, Susan Nathan, Jordana Meyerson, Shivani Jindal, Wei Shen, Amy Hanson, Gilda Cain, and Kate Hinrichs.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.

1. US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. Occupational outlook handbook: physician assistants. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/physician-assistants.htm. Updated June 18, 2019. Accessed August 13, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. 2019 update: the complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2017 to 2032. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/production/media/filer_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-2032.pdf. Published April 2019. Accessed August 15, 2019.

3. Glicken AD, Miller AA. Physician assistants: from pipeline to practice. Acad Med. 2013;88(12):1883-1889.

4. Erikson C, Hamann R, Levitan T, Pankow S, Stanley J, Whatley M. Recruiting and maintaining US clinical training sites: joint report of the 2013 multi-discipline clerkship/clinical training site survey. https://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Recruiting-and-Maintaining-U.S.-Clinical-Training-Sites.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2019.

5. Physician Assistant Education Association. By the numbers: 30th annual report on physician assistant educational programs. 2015. http://paeaonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/2015-by-the-numbers-program-report-30.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed August 15, 2019.

6. Morgan P, Himmerick KA, Leach B, Dieter P, Everett C. Scarcity of primary care positions may divert physician assistants into specialty practice. Med Care Res Rev. 2017;74(1):109-122.

7. Coplan B, Cawley J, Stoehr J. Physician assistants in primary care: trends and characteristics. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):75-79.

8. Morgan P, Leach B, Himmerick K, Everett C. Job openings for PAs by specialty. JAAPA. 2018;31(1):45-47.

9. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2017 AAPA Salary Report. Alexandria, VA; 2017.

10. Barnett ML, Grabowski DC, Mehrotra A. Home-to-home time—measuring what matters to patients and payers. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(1):4-6.

11. Werner RM, Konetzka RT. Trends in post-acute care use among Medicare beneficiaries: 2000 to 2015. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1616-1617.

12. Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant. http://www.arc-pa.org/accreditation/accredited-programs. Accessed May 10, 2019.