User login

Does niacin decrease cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CVD patients?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

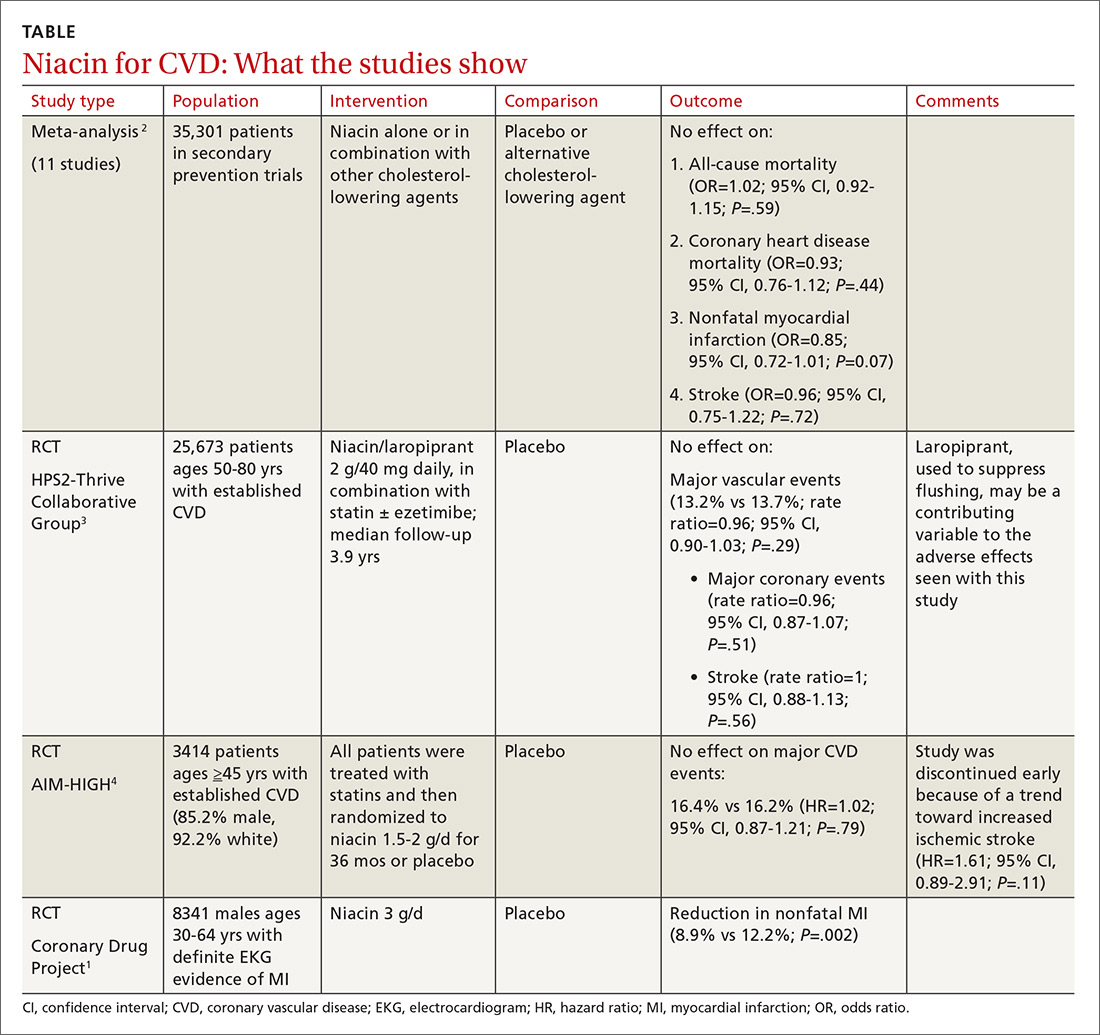

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Before the statin era, the Coronary Drug Project RCT (8341 patients) showed that niacin monotherapy in patients with definite electrocardiographic evidence of previous myocardial infarction (MI) reduced nonfatal MI to 8.9% compared with 12.2% for placebo (P=.002).1 (See TABLE.1-4) It also decreased long-term mortality by 11% compared with placebo (P=.0004).5

Adverse effects such as flushing, hyperglycemia, gastrointestinal disturbance, and elevated liver enzymes interfered with adherence to niacin treatment (66.3% of patients were adherent to treatment with niacin vs 77.8% for placebo). The study was limited by the fact that flushing essentially unblinded participants and physicians.

But adding niacin to a statin has no effect

A 2014 meta-analysis driven by the power of the large HPS2-Thrive study evaluated data from 35,301 patients primarily in secondary prevention trials.2,3 It found that adding niacin to statins had no effect on all-cause mortality, coronary heart disease mortality, nonfatal MI, or stroke. The subset of 6 trials (N=4991) assessing niacin monotherapy did show a reduction in cardiovascular events (odds ratio [OR]=0.62; confidence interval [CI], 0.54-0.82), whereas the 5 studies (30,310 patients) involving niacin with a statin demonstrated no effect (OR=0.94; CI, 0.83-1.06).

No benefit from niacin/statin therapy despite an improved lipid profile

A 2011 RCT included 3414 patients with coronary heart disease on simvastatin who were randomized to niacin or placebo.4 All patients received simvastatin 40 to 80 mg ± ezetimibe 10 mg/d to achieve low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels of 40 to 80 mg/dL.

At 3 years, no benefit was seen in the composite CVD primary endpoint (hazard ratio=1.02; 95% CI, 0.87-1.21; P=.79) even though the niacin group had significantly increased median high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol compared with placebo and lower triglycerides and LDL cholesterol compared with baseline.

A nonsignificant trend toward increased stroke in the niacin group compared with placebo led to early termination of the study. However, multivariate analysis showed independent associations between ischemic stroke risk and age older than 65 years, history of stroke/transient ischemic attack/carotid artery disease, and elevated baseline cholesterol.6

Niacin combined with a statin increases the risk of adverse events

The largest RCT in the 2014 meta-analysis (HPS2-Thrive) evaluated 25,673 patients with established CVD receiving cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe who were randomized to niacin or placebo for a median follow-up period of 3.9 years.3 A pre-randomization run-in phase established effective cholesterol-lowering therapy with simvastatin ± ezetimibe.

Niacin didn’t reduce the incidence of major vascular events even though, once again, it decreased LDL and increased HDL more than placebo. Niacin increased the risk of serious adverse events 56% vs 53% (risk ratio [RR]=6; 95% CI, 3-8; number needed to harm [NNH]=35; 95% CI, 25-60), such as new onset diabetes (5.7% vs 4.3%; P<.001; NNH=71) and gastrointestinal bleeding/ulceration and other gastrointestinal disorders (4.8% vs 3.8%; P<.001; NNH=100).

A subsequent 2014 study examined the adverse events recorded in the AIM-HIGH4 study and found that niacin caused more gastrointestinal disorders (7.4% vs 5.5%; P=.02; NNH=53) and infections and infestations (8.1% vs 5.8%; P=.008; NNH=43) than placebo.7 The overall observed rate of serious hemorrhagic adverse events was low, however, showing no significant difference between the 2 groups (3.4% vs 2.9%; P=.36).

RECOMMENDATIONS

As of November 2013, the Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends against using niacin in combination with statins because of the increased risk of adverse events without a reduction in CVD outcomes. Niacin may be considered as monotherapy in patients who can’t tolerate statins or fibrates based on results of the Coronary Drug Project and other studies completed before the era of widespread statin use.8

Similarly, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines state that patients who are completely statin intolerant may use nonstatin cholesterol-lowering drugs, including niacin, that have been shown to reduce CVD events in RCTs if the CVD risk-reduction benefits outweigh the potential for adverse effects.9

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

1. Coronary Drug Project Research Group. Colofibrate and niacin in coronary heart disease. JAMA. 1975;231:360-81.

2. Keene D, Price C, Shun-Shin MJ, et al. Effect on cardiovascular risk of high density lipoprotein targeted drug treatments niacin, fibrates, and CETP inhibitors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials including 117,411 patients. BMJ. 2014;349:g4379.

3. HPS2-Thrive Collaborative Group. Effects of extended-release niacin with laropiprant in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:203-212.

4. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Niacin in patients with low HDL cholesterol levels receiving intensive statin therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2255-2267.

5. Canner PL, Berge KG, Wender NK, et al. Fifteen-year mortality in Coronary Drug Project patients: long-term benefit with niacin. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1986;8:1245-1255.

6. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Extended-release niacin therapy and risk of ischemic stroke in patients with cardiovascular disease: the Atherothrombosis Intervention in Metabolic Syndrome with low HDL/High Triglycerides: Impact on Global Health Outcome (AIM-HIGH) trial. Stroke. 2013;44:2688-2693.

7. AIM-HIGH Investigators. Safety profile of extended-release niacin in the AIM-HIGH trial. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:288-290.

8. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guideline summary: Lipid management in adults. National Guideline Clearinghouse. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov. Accessed July 20, 2015.

9. Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;25 (suppl 2):S1-S45.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE BASED ANSWER:

No. Niacin doesn’t reduce cardiovascular disease (CVD) morbidity or mortality in patients with established disease (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and subsequent large RCTs).

Niacin may be considered as monotherapy for patients intolerant of statins (SOR: B, one well-done RCT).

Can Yoga Reduce Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression?

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

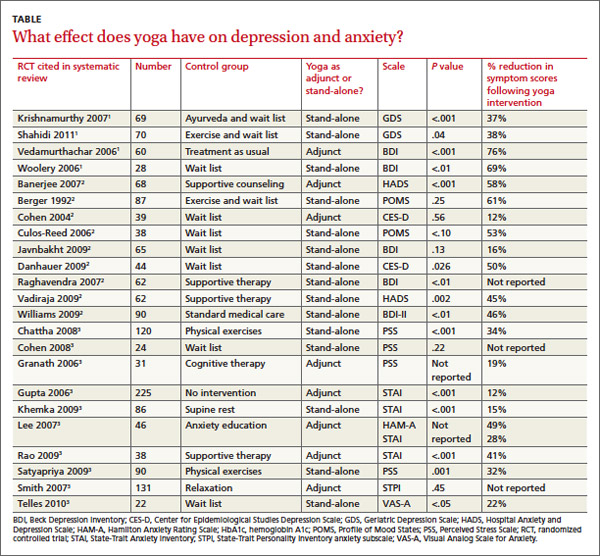

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

Continue for recommendations >>

recommendations

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

Continue for recommendations >>

recommendations

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

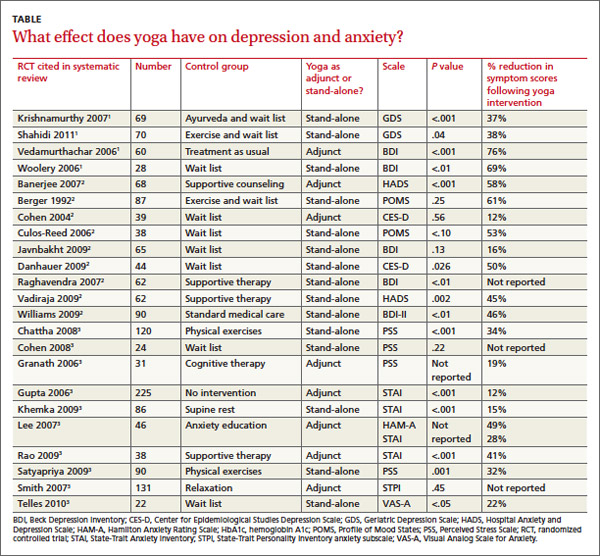

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

Continue for recommendations >>

recommendations

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

Can yoga reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression?

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

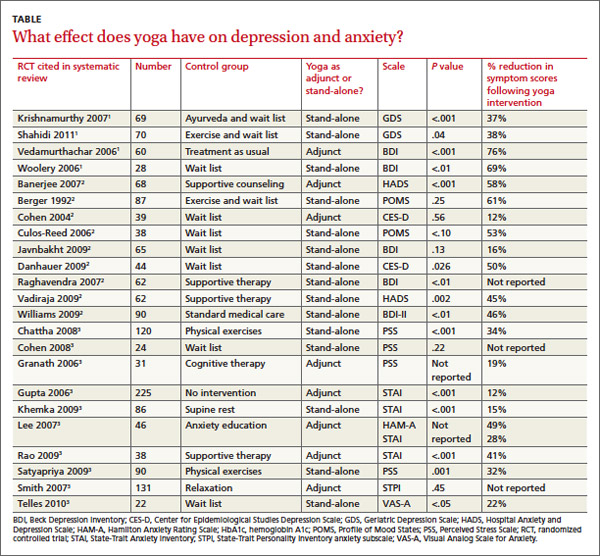

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

Yes, yoga can reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] with significant heterogeneity). Across multiple RCTs using varied yoga interventions and diverse study populations, yoga typically improves overall symptom scores for anxiety and depression by about 40%, both by itself and as an adjunctive treatment. It produces no reported harmful side effects.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Across 3 systematic reviews of yoga for depression, anxiety, and stress, yoga produced overall reductions of symptoms between 12% and 76%, with an average of 39% net reduction in symptom scores across measures (TABLE).1-3 The RCTs included in the systematic reviews were too heterogeneous to allow quantitative analyses of effect sizes.

Yoga found to significantly reduce depression symptoms

Two 2012 systematic reviews of yoga for depression evaluated 13 RCTs with a total of 782 participants, ages 18 to 80 years with mild to moderate depression. In the 12 RCTs that reported gender, 82% of participants were female; in 6 RCTs a total of 313 patients had cancer.1,2

The RCTs compared yoga to wait-list controls, counseling, education, exercise, or usual care. They evaluated yoga both as a stand-alone intervention and an adjunct to usual care. Yoga sessions varied from 1 hour weekly to 90 minutes daily over 2 to 24 weeks and included physical postures, relaxation, and breathing techniques.

Eight moderate- to high-quality RCTs with a total of 483 participants reported statistically significant reductions in depression symptoms in the yoga groups compared with control groups. In 3 RCTs, yoga was equivalent to wait-list controls; 2 RCTs showed results equivalent to exercise and superior to wait-list controls.

Yoga alleviates anxiety and stress without adverse effects

A 2012 systematic review of yoga for stress and anxiety evaluated 10 RCTs with a total of 813 heterogeneous participants, ages 18 to 76 years, including pregnant women, breast cancer patients, flood survivors, healthy volunteers, patients with chronic illnesses, perimenopausal women, adults with metabolic syndrome, and people working in finance, all with a range of anxiety and stress symptoms.3 The RCTs compared yoga, as an adjunctive or stand-alone treatment, with wait-list controls, relaxation, therapy, anxiety education, rest, or exercise. Yoga regimens varied from a single 20-minute session to 16 weeks of daily 1-hour sessions, with most regimens lasting 6 to 10 weeks.

Of the 10 RCTs reviewed, 7 moderate- to high-quality studies with a total of 627 participants found statistically significant reductions in anxiety and stress in yoga groups compared with control groups. Of the remaining 3 studies, 1 found yoga equivalent to cognitive therapy; 1 found a nonsignificant benefit for yoga compared with wait-list controls; and 1 found no improvement with either yoga or relaxation.

Study limitations included a range of symptom severity, variable type and length of yoga, lack of participant blinding, wait-list rather than active-treatment controls, and a lack of consistent long-term follow-up data. The RCTs didn’t report any adverse effects of yoga, and yoga is considered safe when taught by a competent instructor.3,4

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments recommend yoga as an effective adjunctive treatment to decrease the severity of depression symptoms.5,6

The Veterans Health Administration and the US Department of Defense recommend yoga as a potential adjunctive treatment to manage the hyperarousal symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7

The Work Loss Data Institute recommends yoga as an intervention for workers compensation conditions including occupational stress, major depressive disorder, PTSD, and other mental disorders.8

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

1. Balasubramaniam M, Telles S, Doraiswamy PM. Yoga on our minds: a systematic review of yoga for neuropsychiatric disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2012;3:117.

2. D’Silva S, Poscablo C, Habousha R, et al. Mind-body medicine therapies for a range of depression severity: a systematic review. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:407-423.

3. Li AW, Goldsmith CA. The effects of yoga on anxiety and stress. Altern Med Rev. 2012;17:21-35.

4. Brown RP, Gerbarg PL. Sudarshan Kriya Yogic breathing in the treatment of stress, anxiety, and depression. Part II—clinical applications and guidelines. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:711-717.

5. Mitchell J, Trangle M, Degnan B, et al. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Adult depression primary care. Available at: https://www.icsi.org/_asset/fnhdm3/Depr-Interactive0512b.pdf. Updated September 2013. Accessed March 6, 2014.

6. Ravindran AV, Lam RW, Filteau MJ, et al; Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT). Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) clinical guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. V. Complementary and alternative medicine treatments. J Affect Disord. 2009;117(suppl 1):S54-S64.

7. US Department of Veterans Affairs. VA/DoD clinical practice guideline for management of post-traumatic stress disorder and acute stress reaction. US Department of Veterans Affairs Web site. Available at: http://www.healthquality.va.gov/ptsd/. Accessed March 6, 2014.

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Mental illness & stress. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Web site. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/content.aspx?id=47588. Updated May 2011. Accessed June 17, 2014

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Which treatments help women with reduced libido?

SEVERAL TREATMENTS produce modest, but statistically significant, clinical increases in sexual desire and function in women.

The testosterone transdermal patch improves hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in postmenopausal women (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, 2 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Bupropion may be effective for HSDD in premenopausal women (SOR: B, 2 RCTs).

Sildenafil improves HSDD associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Evidence Summary

Two RCTs examined the effect of testosterone on postmenopausal women with HSDD. One trial randomized 272 women ages 40 to 70 years to a 300-mcg transdermal testosterone patch (TTP; 142 women) or placebo (130 women).1 At 6 months, women using the TTP reported more sexually satisfying episodes (1.69 vs 0.59 episodes in 4 weeks; P=.0089) and a minimal increase in sexual desire scores (12.2 vs 4.56 on a 100-point sexual desire scale; P=.0007) compared with women using placebo.

A second trial randomized 814 postmenopausal women (mean age 54.2 years) to placebo (277 women), a 150-mcg TTP (267 women), or a 300-mcg TTP (270 women).2 At 24 weeks, women taking 300 mcg (but not 150 mcg) of testosterone reported a greater number of satisfying sexual episodes than women taking placebo (2.1 vs 0.7; P<.0001). The 300-mcg TTP caused more unwanted hair growth than placebo (19.9% vs 10.5%; no P value given). The study didn’t continue long enough to assess cardiovascular risks.

Bupropion may improve sexual function in premenopausal women

Two RCTs found benefit from bupropion for premenopausal women with HSDD. In the first, investigators randomized 232 women 20 to 40 years of age to bupropion sustained release (SR) 150 mg daily or placebo. They assessed sexual function at 12 weeks with the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women—a scale with scores ranging from -16 (poor functioning) to +75 (maximum functioning), with a mean value in normal women of 33.6.3 Women taking bupropion reported greater increases in scores than women taking placebo (15.8 to 33.9, vs 15.5 to 16.9; P=.001) and no serious adverse events.

A second RCT randomized 66 premenopausal women (mean age 36.1 years) to take either bupropion SR 150 mg daily, increased to 300 mg daily after one week, or placebo.4 Researchers measured sexual responsiveness (arousal, pleasure, and orgasm) using the Change in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire at baseline and on Days 28, 56, 84, and 112. Women taking bupropion had higher scores by Day 28 than women taking placebo and maintained the difference through Day 112 (P=.05). The authors indicated that the clinical significance of the change is unclear.

Sildenafil increases low sexual desire associated with antidepressants

A double-blind RCT enrolling 98 premenopausal women (mean age 36.7 years) with sexual dysfunction related to SSRIs found that sildenafil (50-100 mg) improved sexual functioning more than placebo using the 7-point Clinical Global Impression score (sildenafil: 1.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6-2.3; placebo: 1.1 points; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P=.001).5

The investigators didn’t specify whether the change was clinically significant. However, another RCT that studied 881 pre- and postmenopausal women with HSDD unassociated with SSRIs found no difference between sildenafil (10-100 mg) and placebo.6

Recommendations

The US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t recommend androgens for female sexual dysfunction.

The Endocrine Society says that bupropion may be used for HSDD (although it isn’t licensed for such use) and doesn’t recommend long-term use of testosterone because of inadequate safety studies.7

The North American Menopause Society recommends testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women with HSDD.8

1. Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13:121-131.

2. Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone for low libido in women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

3. Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY, Asgari MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of bupropion for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in ovulating women. BJU Int. 2010;106:832-839.

4. Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. Buproprion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:339-342.

5. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

6. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:367-377.

7. Wierman M, Basson R, Davis SR, et al. Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3697-3710.

8. Braunstein GD. The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline and The North American Menopause Society position statement on androgen therapy in women: another one of Yogi’s forks. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4091-4093.

SEVERAL TREATMENTS produce modest, but statistically significant, clinical increases in sexual desire and function in women.

The testosterone transdermal patch improves hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in postmenopausal women (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, 2 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Bupropion may be effective for HSDD in premenopausal women (SOR: B, 2 RCTs).

Sildenafil improves HSDD associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Evidence Summary

Two RCTs examined the effect of testosterone on postmenopausal women with HSDD. One trial randomized 272 women ages 40 to 70 years to a 300-mcg transdermal testosterone patch (TTP; 142 women) or placebo (130 women).1 At 6 months, women using the TTP reported more sexually satisfying episodes (1.69 vs 0.59 episodes in 4 weeks; P=.0089) and a minimal increase in sexual desire scores (12.2 vs 4.56 on a 100-point sexual desire scale; P=.0007) compared with women using placebo.

A second trial randomized 814 postmenopausal women (mean age 54.2 years) to placebo (277 women), a 150-mcg TTP (267 women), or a 300-mcg TTP (270 women).2 At 24 weeks, women taking 300 mcg (but not 150 mcg) of testosterone reported a greater number of satisfying sexual episodes than women taking placebo (2.1 vs 0.7; P<.0001). The 300-mcg TTP caused more unwanted hair growth than placebo (19.9% vs 10.5%; no P value given). The study didn’t continue long enough to assess cardiovascular risks.

Bupropion may improve sexual function in premenopausal women

Two RCTs found benefit from bupropion for premenopausal women with HSDD. In the first, investigators randomized 232 women 20 to 40 years of age to bupropion sustained release (SR) 150 mg daily or placebo. They assessed sexual function at 12 weeks with the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women—a scale with scores ranging from -16 (poor functioning) to +75 (maximum functioning), with a mean value in normal women of 33.6.3 Women taking bupropion reported greater increases in scores than women taking placebo (15.8 to 33.9, vs 15.5 to 16.9; P=.001) and no serious adverse events.

A second RCT randomized 66 premenopausal women (mean age 36.1 years) to take either bupropion SR 150 mg daily, increased to 300 mg daily after one week, or placebo.4 Researchers measured sexual responsiveness (arousal, pleasure, and orgasm) using the Change in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire at baseline and on Days 28, 56, 84, and 112. Women taking bupropion had higher scores by Day 28 than women taking placebo and maintained the difference through Day 112 (P=.05). The authors indicated that the clinical significance of the change is unclear.

Sildenafil increases low sexual desire associated with antidepressants

A double-blind RCT enrolling 98 premenopausal women (mean age 36.7 years) with sexual dysfunction related to SSRIs found that sildenafil (50-100 mg) improved sexual functioning more than placebo using the 7-point Clinical Global Impression score (sildenafil: 1.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6-2.3; placebo: 1.1 points; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P=.001).5

The investigators didn’t specify whether the change was clinically significant. However, another RCT that studied 881 pre- and postmenopausal women with HSDD unassociated with SSRIs found no difference between sildenafil (10-100 mg) and placebo.6

Recommendations

The US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t recommend androgens for female sexual dysfunction.

The Endocrine Society says that bupropion may be used for HSDD (although it isn’t licensed for such use) and doesn’t recommend long-term use of testosterone because of inadequate safety studies.7

The North American Menopause Society recommends testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women with HSDD.8

SEVERAL TREATMENTS produce modest, but statistically significant, clinical increases in sexual desire and function in women.

The testosterone transdermal patch improves hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD) in postmenopausal women (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, 2 randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Bupropion may be effective for HSDD in premenopausal women (SOR: B, 2 RCTs).

Sildenafil improves HSDD associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (SOR: B, 1 RCT).

Evidence Summary

Two RCTs examined the effect of testosterone on postmenopausal women with HSDD. One trial randomized 272 women ages 40 to 70 years to a 300-mcg transdermal testosterone patch (TTP; 142 women) or placebo (130 women).1 At 6 months, women using the TTP reported more sexually satisfying episodes (1.69 vs 0.59 episodes in 4 weeks; P=.0089) and a minimal increase in sexual desire scores (12.2 vs 4.56 on a 100-point sexual desire scale; P=.0007) compared with women using placebo.

A second trial randomized 814 postmenopausal women (mean age 54.2 years) to placebo (277 women), a 150-mcg TTP (267 women), or a 300-mcg TTP (270 women).2 At 24 weeks, women taking 300 mcg (but not 150 mcg) of testosterone reported a greater number of satisfying sexual episodes than women taking placebo (2.1 vs 0.7; P<.0001). The 300-mcg TTP caused more unwanted hair growth than placebo (19.9% vs 10.5%; no P value given). The study didn’t continue long enough to assess cardiovascular risks.

Bupropion may improve sexual function in premenopausal women

Two RCTs found benefit from bupropion for premenopausal women with HSDD. In the first, investigators randomized 232 women 20 to 40 years of age to bupropion sustained release (SR) 150 mg daily or placebo. They assessed sexual function at 12 weeks with the Brief Index of Sexual Functioning for Women—a scale with scores ranging from -16 (poor functioning) to +75 (maximum functioning), with a mean value in normal women of 33.6.3 Women taking bupropion reported greater increases in scores than women taking placebo (15.8 to 33.9, vs 15.5 to 16.9; P=.001) and no serious adverse events.

A second RCT randomized 66 premenopausal women (mean age 36.1 years) to take either bupropion SR 150 mg daily, increased to 300 mg daily after one week, or placebo.4 Researchers measured sexual responsiveness (arousal, pleasure, and orgasm) using the Change in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire at baseline and on Days 28, 56, 84, and 112. Women taking bupropion had higher scores by Day 28 than women taking placebo and maintained the difference through Day 112 (P=.05). The authors indicated that the clinical significance of the change is unclear.

Sildenafil increases low sexual desire associated with antidepressants

A double-blind RCT enrolling 98 premenopausal women (mean age 36.7 years) with sexual dysfunction related to SSRIs found that sildenafil (50-100 mg) improved sexual functioning more than placebo using the 7-point Clinical Global Impression score (sildenafil: 1.9 points; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.6-2.3; placebo: 1.1 points; 95% CI, 0.8-1.5; P=.001).5

The investigators didn’t specify whether the change was clinically significant. However, another RCT that studied 881 pre- and postmenopausal women with HSDD unassociated with SSRIs found no difference between sildenafil (10-100 mg) and placebo.6

Recommendations

The US Food and Drug Administration doesn’t recommend androgens for female sexual dysfunction.

The Endocrine Society says that bupropion may be used for HSDD (although it isn’t licensed for such use) and doesn’t recommend long-term use of testosterone because of inadequate safety studies.7

The North American Menopause Society recommends testosterone therapy for postmenopausal women with HSDD.8

1. Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13:121-131.

2. Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone for low libido in women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

3. Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY, Asgari MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of bupropion for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in ovulating women. BJU Int. 2010;106:832-839.

4. Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. Buproprion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:339-342.

5. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

6. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:367-377.

7. Wierman M, Basson R, Davis SR, et al. Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3697-3710.

8. Braunstein GD. The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline and The North American Menopause Society position statement on androgen therapy in women: another one of Yogi’s forks. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4091-4093.

1. Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric. 2010;13:121-131.

2. Davis SR, Moreau M, et al. Testosterone for low libido in women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2005-2017.

3. Safarinejad MR, Hosseini SY, Asgari MA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of bupropion for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder in ovulating women. BJU Int. 2010;106:832-839.

4. Segraves RT, Clayton A, Croft H, et al. Buproprion sustained release for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire in premenopausal women. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24:339-342.

5. Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, et al. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. JAMA. 2008;300:395-404.

6. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2002;11:367-377.

7. Wierman M, Basson R, Davis SR, et al. Androgen therapy in women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:3697-3710.

8. Braunstein GD. The Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline and The North American Menopause Society position statement on androgen therapy in women: another one of Yogi’s forks. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4091-4093.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network