User login

Perifollicular petechiae and easy bruising

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

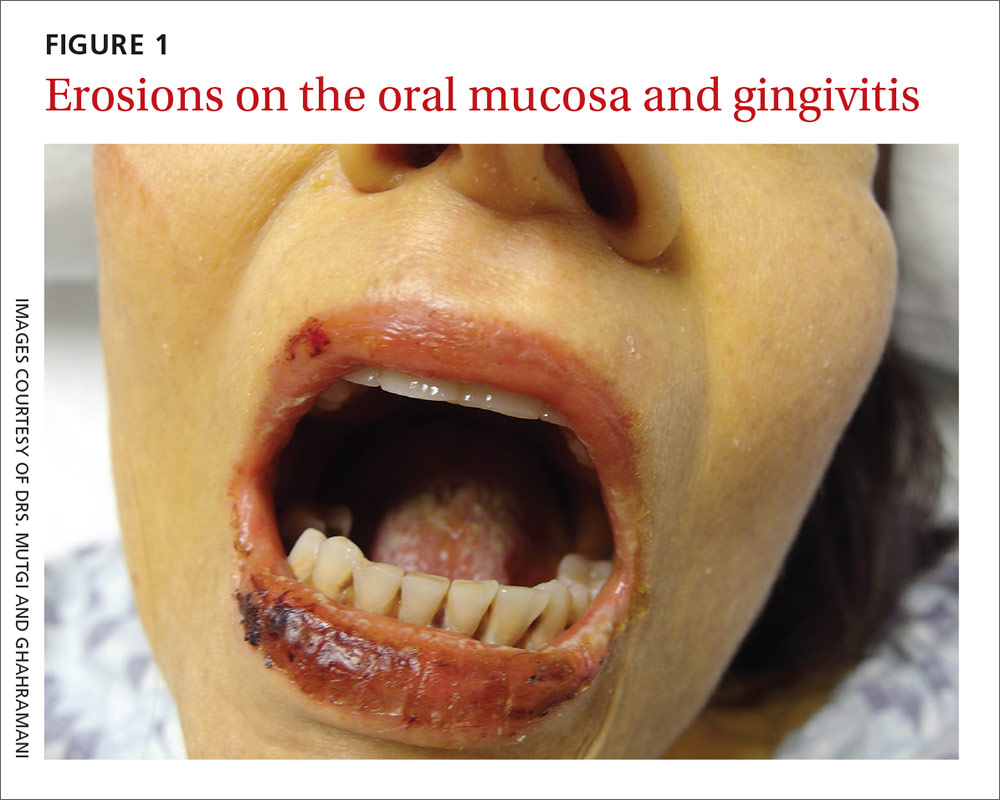

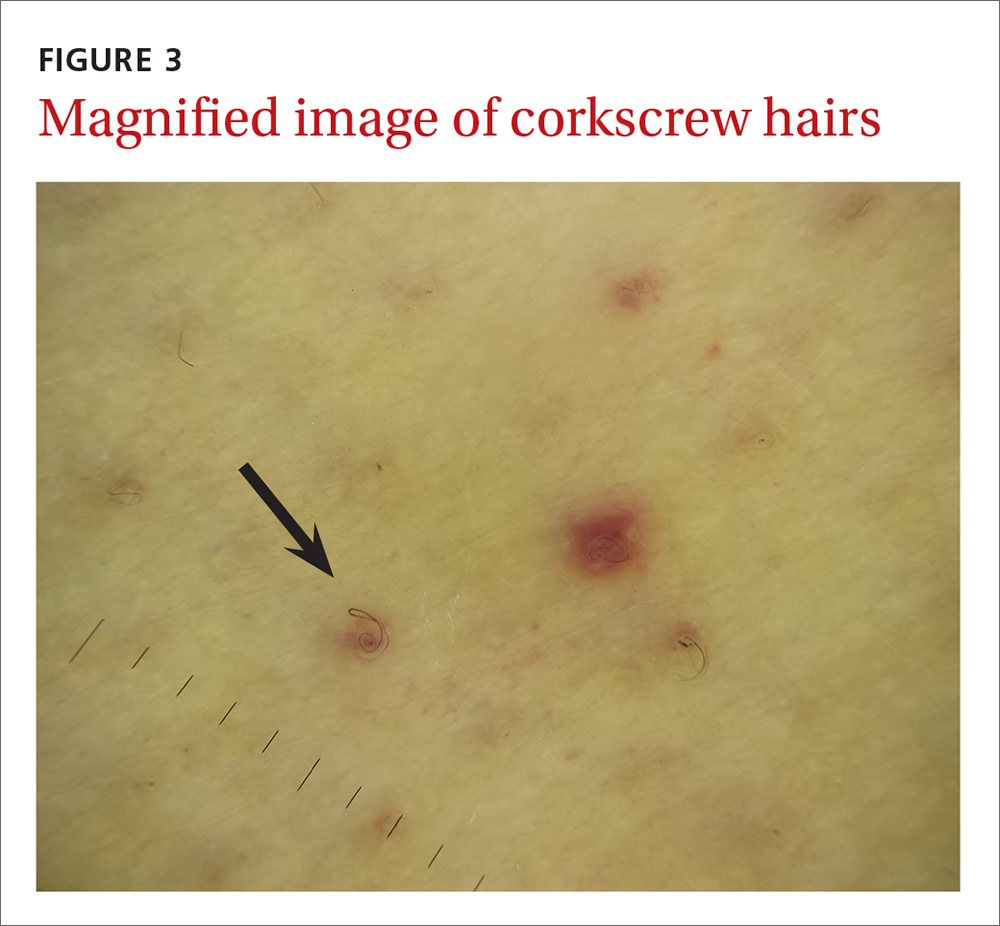

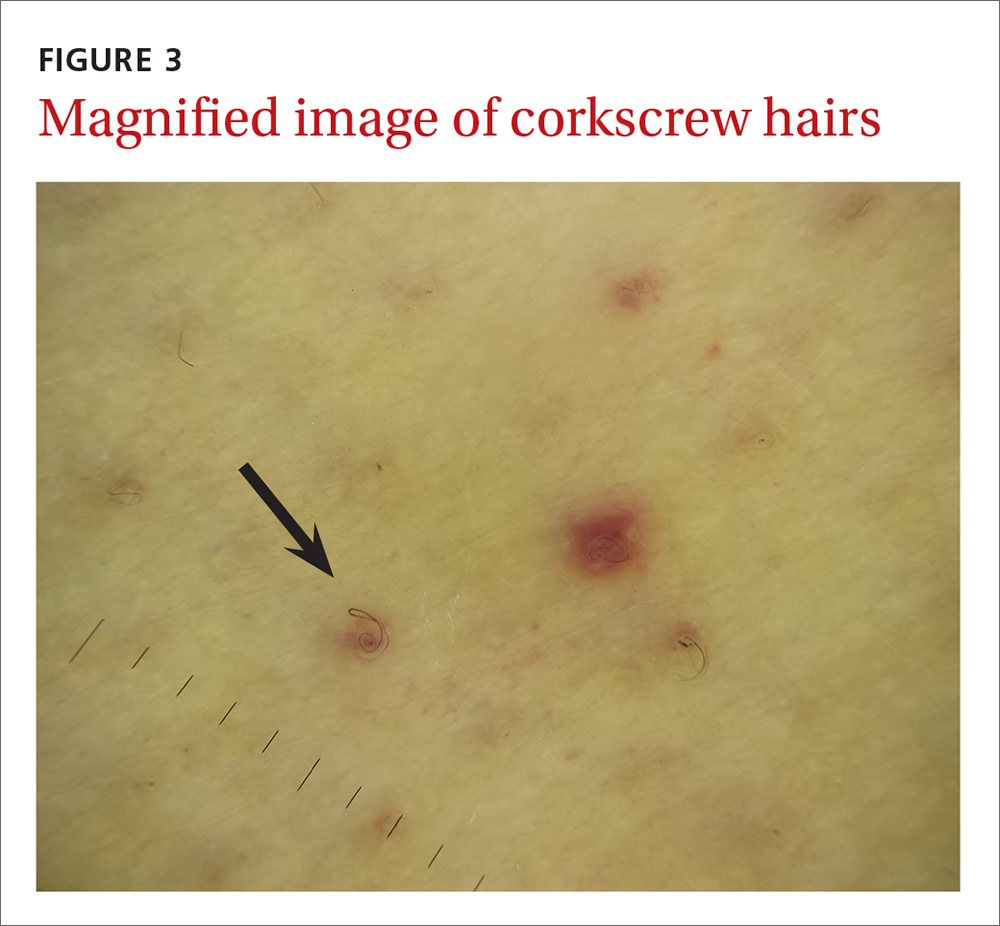

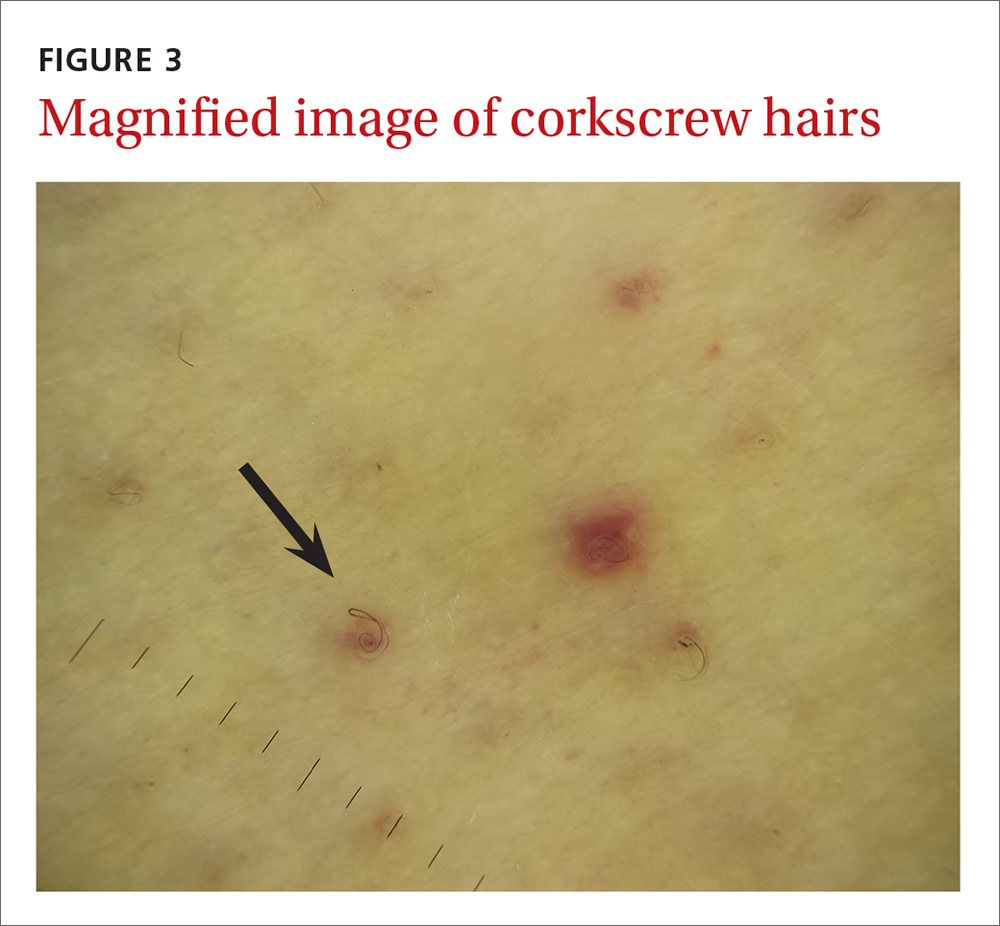

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

A 45-year-old woman presented to our hospital with recurrent cirrhosis and sepsis secondary to a hepatic abscess from Pseudomonas aeromonas and Candida albicans. Ten years earlier, she had received a liver transplant due to sclerosing cholangitis. The patient had a history of nausea from her liver disease and malnutrition due to a diet that consisted predominantly of cereal with minimal fresh fruits and vegetables. Her family reported that she bruised easily and had worsening dry, flaky skin.

The physical examination revealed jaundice, scleral icterus, purpuric macules, superficial desquamation, gingivitis (FIGURE 1), and perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs (FIGURES 2 and 3). The patient also had acute kidney injury, delirium, and pancytopenia. She was admitted to the hospital and was started on piperacillin-tazobactam and fluconazole for sepsis, as well as rifaximin and lactulose for hepatic encephalopathy.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Vitamin C deficiency

We diagnosed this patient with vitamin C deficiency (scurvy) based on the fact that she had perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs, which is a pathognomonic feature of the deficiency. The diagnosis was confirmed with a blood vitamin C level of 10 mcmol/L (normal range: 11-114 mcmol/L). It’s important to note that a vitamin C level drawn after hospitalization may be falsely normal due to an improved diet during hospitalization, so a normal vitamin C level doesn’t always rule out a deficiency.

Vitamin C is absorbed from the small intestine and excreted renally. A low vitamin C level occurs in the presence of several conditions—specifically alcoholism and critical illnesses such as sepsis, trauma, major surgery, or stroke—possibly due to decreased absorption and increased oxidative stress. Vitamin C is necessary for multiple hydroxylation reactions, including hydroxylation of proline and lysine in collagen synthesis, beta-hydroxybutyric acid in carnitine synthesis, and dopamine-beta-hydroxylase in catecholamine synthesis.1

Early vitamin C deficiency presents with nonspecific symptoms, such as malaise, fatigue, and lethargy, followed by the development of anemia, myalgia, bone pain, easy bruising, edema, petechiae, perifollicular hemorrhages, corkscrew hairs, gingivitis, poor wound healing, and mood changes. If untreated, jaundice, neuropathy, hemolysis, seizures, and death can occur.2-4

Perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs are characteristic of the Dx

The differential diagnosis of vitamin C deficiency includes vasculitis, thrombocytopenia, multiple myeloma, and folliculitis.

Vasculitis typically presents with palpable purpura and is not exclusively perifollicular.5 Thrombocytopenia may present with petechiae, but the petechiae are generally not perifollicular and hair shaft abnormalities are generally absent. Multiple myeloma may present with purpura with minimal trauma and larger ecchymosis that isn’t petechial in appearance. Folliculitis typically presents with folliculocentric pustules that have surrounding erythema, but no hemorrhaging.

Suspect vitamin C deficiency in patients with alcoholism, a poor diet, and those who are critically ill.6 During the physical exam, look for ecchymosis, edema, gingivitis, impaired wound healing, jaundice, and the tell-tale sign of perifollicular hemorrhages with corkscrew hairs.7

If lab values and/or circumstances leave doubt as to whether a true vitamin C deficiency exists, a punch biopsy of an area of perifollicular hemorrhage may be performed. The punch biopsy should demonstrate follicular hyperkeratosis overlying multiple fragmented hair shafts that are surrounded by a perifollicular lymphohistiocytic infiltrate with extravasated red blood cells.4

Treat with vitamin C

Vitamin C can be replaced via the oral or intravenous (IV) route. There is currently no consensus on a single best replacement regimen, but several effective regimens have been reported in the literature.8,9

We started our patient on IV vitamin C 1 g/d, which improved her cutaneous lesions. Unfortunately, though, she succumbed to complications of her liver disease shortly after starting the therapy.

CORRESPONDENCE

Krishna AJ Mutgi, MD, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 555 S. 18th Street, Columbus, OH 43205; Krishna.Mutgi@nationwidechildrens.org.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.

1. Chambial S, Dwivedi S, Shukla KK, et al. Vitamin C in disease prevention and cure: an overview. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2013;28:314-328.

2. Touyz LZ. Oral scurvy and periodontal disease. J Can Dent Assoc. 1997;63:837-845.

3. Singh S, Richards SJ, Lykins M, et al. An underdiagnosed ailment: scurvy in a tertiary care academic center. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349:372-373.

4. Al-Dabagh A, Milliron BJ, Strowd L, et al. A disease of the present: scurvy in “well-nourished” patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:e246-e247.

5. Francescone MA, Levitt J. Scurvy masquerading as leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report and review of the literature. Cutis. 2005;76:261-266.

6. Holley AD, Osland E, Barnes J, et al. Scurvy: historically a plague of the sailor that remains a consideration in the modern intensive care unit. Intern Med J. 2011;41:283-285.

7. Cinotti E, Perrot JL, Labeille B, et al. A dermoscopic clue for scurvy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:S37-S38.

8. De Luna RH, Colley BJ 3rd, Smith K, et al. Scurvy: an often forgotten cause of bleeding. Am J Hematol. 2003;74:85-87.

9. Stephen R, Utecht T. Scurvy identified in the emergency department: a case report. J Emerg Med. 2001;21:235-237.