User login

Acute pain management in hospitalized adult patients with opioid dependence: a narrative review and guide for clinicians

Up to 40% of Americans experience chronic pain of some kind.1 In the United States, opioid analgesics are the most prescribed class of medications,2 with 245 million prescriptions filled in 2014 alone. Thirty-five percent of these prescriptions were for long-term therapy.3 It is now apparent that opioid pain medication use presents serious risks. In 2014, 10.3 million persons reported using prescription opioids for nonmedical reasons.4 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died of overdose related to opioid medication.5 In addition, heroin use in the United States has increased over the past decade.6 Opioid agonist maintenance therapy is also increasingly used to treat patients with opioid use disorder.

Given the prevalence of opioid use in the United States, it is important for hospitalists to be able to appropriately and safely manage acute pain in patients who have been exposed long-term to opioids, whether it is therapeutic or non-medical in origin. Although nonopioid medications and nondrug treatments are essential components of managing all acute pain, opioids continue to be the mainstay of treatment for severe acute pain in both opioid-naïve and opioid-dependent patients.

Given the paucity of published trials meeting the typical criteria, we did not perform a structured meta-analysis but, instead, a case-based narrative review of the relevant published literature. Our goal in performing this review is to guide hospitalists in the appropriate and safe use of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain in hospitalized patients who are opioid-dependent.

DEFINITIONS

When managing acute pain in patients with opioid dependence it is important to have a clear understanding of the definitions related to opioid use. Addiction, physical dependence and tolerance have been defined by a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, American Academy of Pain Medicine, and American Pain Society7: Addiction is a primary, chronic, biological disease, with genetic, psychosocial and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

Physical Dependence is a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

Tolerance is the state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress with symptoms including a strong desire for opioids, inability to control or reduce use of opioids, continued use despite adverse consequences, and development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Physical dependence and tolerance are common consequences of long-term opioid use. In contrast, OUD has been reported to affect only 2% to 6% of individuals exposed to opioids.9 The underlying mechanisms that lead an individual to abuse or become addicted to opioids largely due to the effects opioids have on endogenous μ-opioid receptors. As analgesics, opioids exert their effects by binding primarily to these μ-opioid receptors, with a large concentration in the brain regions regulating pain perception.10,11 There is also a large concentration of μ-opioid receptors in the brain reward regions, leading to perceptions of pleasure and euphoria. Repeated administration of opioids conditions the brain to a learned association between receiving the opiate and euphoria.12,13 This association becomes stronger as the frequency and duration of administration increases over time, ultimately leading to the desire or craving of the opioid’s effect.

The effect of tolerance also contributes to the pathophysiology of opioid abuse as it leads to a decrease in opioid potency with repeated administration.14-16 To achieve analgesia as well as the reward effect, opioid dosage and/or frequency must be increased, strengthening the association between receipt of opioid and reward. Tolerance to the reward effect occurs quickly, whereas tolerance to respiratory depression occurs much more slowly.17 This mismatch in tolerance of effect may lead to increase in opioid doses to maintain analgesia or euphoria, and also places patients at a higher risk of overdose.18

ACUTE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Clinical Example: Heroin User

A 47-year-old man is admitted with fever, chills, and severe mid-back pain and receives a diagnosis of sepsis. The patient admits to using intravenous heroin 500 mg (five 100 mg “bags”) on a daily basis. He is admitted, fluid resuscitated and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Blood cultures quickly grow Staphylococcus aureus. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine shows cervical vertebral osteomyelitis. On examination, the patient is diaphoretic and complains of diffuse myalgias and diarrhea. The patient’s back pain is so severe that he cannot ambulate. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

Managing acute pain in a patient using heroin can be challenging for many reasons. First, both physicians and pharmacists report a lack of confidence in their ability to prescribe opioids safely or to treat patients with a history of opioid abuse.19 Second, there is a paucity of evidence in treating acute pain in heroin users. Finally, due to the clandestine manufacturing of illicit drugs, the actual purity of the drug is often unknown making it difficult to assess the dose of opioids in heroin users. Drug Enforcement Agency seizure data indicate a wide range of heroin purity: 30% to 70%.20

In the hospital setting, acute pain is often undertreated in patients with a history of active opioid abuse. This may be due to providers’ misconceptions regarding pain and behavior in opioid addicts, including worrying that the patient’s pain is exaggerated in order to obtain drugs, thinking that a regular opioid habit eliminates pain, believing that opioid therapy is not effective in drug addicts, or worrying that prescribing opioids will exacerbate drug addiction.21 Data demonstrates that the presence of opioid addiction seems to worsen the experience of acute pain.22 These patients also often have a higher tolerance and thus require higher dosages and more frequent dosing of opioids to adequately treat their pain.23

Converting daily heroin use to morphine equivalents is necessary to establish a baseline analgesic requirement and to prevent withdrawal. It is challenging to convert illicit heroin to morphine equivalents however, as one must take into account the wide variation in purity and understand that the stated use of heroin (e.g. 500 mg daily) reflects weight and not dosage of heroin.20

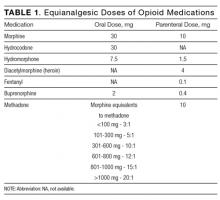

In these patients, treatment of acute pain should be individualized according to presenting illness and comorbidities. Previous data and an average purity of 40% suggest that the parenteral morphine equivalent to a bag of heroin (100 mg) is 15 to 30 mg.20,24,25 Common equianalgesic doses of opioid medications are listed in Table 1. Because of increased tolerance, the frequency of administration should be shortened, from every 4 hours to every 2 or 3 hours. Except for a shorter onset of action, there has not been a difference shown in superiority between oral and parenteral routes of administration. Finally, patients should receive both long-acting basal and short-acting as-needed analgesics based on their daily use of opioids.23

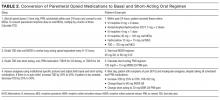

In our clinical example, IV heroin 500 mg daily converts to parenteral morphine 75 to 150 mg every 24 hours. We recommend initiating IV morphine 10 mg every 3 hours as needed for pain and withdrawal symptoms, with early reassessment regarding need for a higher dose or a shorter frequency based on symptoms. Nonopioid analgesics should also be administered with the goal of decreasing the opioid requirement. As soon as possible, the patient should be changed to oral basal and short-acting opioids as needed for breakthrough pain. The appropriate dose of long acting basal analgesia can be determined the following day based on the patient’s total daily dose (TDD) of opioids. An example of converting from intravenous PRN morphine to oral basal and short acting opioids is shown in Table 2.

In communicating with a patient with opioid-use disorder with acute pain, it is best to outline the pain management plan at admission including: the plan to effectively treat the patient’s acute pain, prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms, change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible, discussion of non-opioid and non-drug treatments, reinforcement that opioids will be tapered as the acute pain episode resolves, and a detailed plan for discharge Later in this article, we describe discharge planning.

Clinical Example: Patient on Chronic Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

A 64 year-old man was involved in a motorcycle accident and suffered a right distal tibia-fibula fracture and several broken ribs with a secondary pneumothorax. The patient’s past medical history is significant for chronic low back pain for which he states he takes morphine sustained release 30 mg orally every 8 hours and morphine immediate release 15 mg orally four times daily for breakthrough pain. The patient states his pain is much worse than prior to the accident. Trauma surgery requests recommendations on appropriate pain management. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

When treating acute pain in patients with chronic pain on opioid therapy, it is vital to establish the patient’s baseline pain level and to accurately reconcile the patient’s outpatient daily opioid use. The patient’s prescription record should be verified in the state’s prescription drug monitoring program. On admission, a urine drug test should be obtained to assess for use of other potential illicit substances (eg, cocaine). Patients who test positive for illicit substances are at high risk for a substance use disorder. Management and discharge plans should be as outlined in the above case. It is important to know that the first-tier immunoassay urine toxicology screens used by hospitals test for natural opioids (morphine, codeine, heroin). Semi-synthetic (example, oxycodone) or synthetic (example, fentanyl) opioids are unlikely to be detected and thus the urine drug screen may not be helpful to determine adherence to certain prescription opioids. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry is the most sensitive and specific type of urine screen and can be ordered to confirm a prescribed opioid if needed.26

Pain management should begin with calculating the TDD of oral opioids that the patient was taking prior to admission, and converting to morphine equivalents. For moderate acute pain, TDD can be increased by 25% to 50%. The revised TDD can then be prescribed as a long-acting opioid every 8 to 12 hours to provide basal analgesia. The dose of additional immediate-release medication available throughout the day to manage breakthrough pain is determined by dividing the new TDD into every 3 to 4 hours as-needed dosing (Table 2).

If severe pain is anticipated, patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is an effective alternative to deliver opioids. The use of PCA allows self-titration, on demand analgesia, and minimizes the likelihood of under-dosing the patient.27 The revised TDD is a useful starting point when calculating the PCA dosage regimen. Ideally, the revised TDD should be prescribed as a long acting oral opioid medication every 8 to 12 hours for basal analgesia, with PCA administered as an as-needed bolus. If a patient cannot tolerate oral medications, PCA can provide continuous infusion of medication to provide basal analgesia, though the risk of oversedation and respiratory depression is increased.28

For our clinical example, we recommend increasing the preadmission TDD of opioids (180 mg morphine equivalents) by 25% (225 mg) and administering as morphine 75 mg sustained-release every 8 hours to provide baseline analgesia and prevent withdrawal symptoms. The acute pain can be managed by initiating morphine PCA without continuous infusion at 0.5 mg bolus every 8 minutes as needed for breakthrough pain or oral morphine 30 mg immediate-release tablets every 3 hours as needed for pain. The patient should be assessed frequently, and naloxone kept readily available. In addition, nonopioid and nondrug treatments should be optimized.

When communicating with patients with underlying chronic pain on chronic opioid therapy, it is important to discuss the treatment plan early, including addressing that they will likely not be pain free during their hospitalization, but rather goals of pain relief and improved function should be established. The plan to change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible and importance of multi-modal treatment should be emphasized. The patient should be informed that medication changes are for the short-term only and that the underlying chronic pain will likely remain unchanged.

Clinical Example: Patient on Medication-Assisted Therapy

A 42-year-old woman presents with acute epigastric pain and receives a diagnosis of acute gallstone pancreatitis. She states that her pain is very severe and appears uncomfortable. Her past medical history is significant for heroin addiction, but she has been successfully treated for opioid-use disorder with buprenorphine 16 mg daily for the past three years. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with her about her pain management?

Medication-assisted therapies (MATs) for treatment of opioid abuse, which include methadone and buprenorphine (Table 3), have been shown to be effective in helping patients recover in opioid-use disorder, are cost-effective and reduce the risk of opioid overdose.29 However, treatment for acute pain in patients who are receiving methadone or buprenorphine MAT is a challenge because of pharmacokinetic changes that occur with prolonged use. It is important to know that patients receiving opioid agonist MAT are usually treated with 1 dose every 24 to 48 hours and do not receive sustained analgesia.30

In the case of patients on methadone as MAT, the methadone should be continued at the prescribed daily dose and additional short-acting opioid analgesics given to provide appropriate pain relief.27,31 Because of opioid tolerance, patients receiving MAT often require increased and more frequent doses of short-acting opioid analgesics to achieve adequate pain control.

Buprenorphine is a mu-opioid receptor partial agonist. The partial agonist properties of buprenorphine result in a “ceiling effect” that limits maximal analgesic and euphoric potential. Buprenorphine’s high affinity for the mu receptor also may result in competition with full opioid agonist analgesics, creating a challenge in treating acute pain. Because of the erratic dissociation of buprenorphine from the mu receptor, naloxone should be available and patients should be frequently monitored when the two agents are administered together. Recommendations regarding acute pain management in patients being treated with buprenorphine are largely based on expert opinion. Treatment options include32-34:

- Continue maintenance therapy with buprenorphine and treat acute pain with short acting opioid agonists. Higher doses of opioid agonists and more frequent dosing may be needed to provide adequate pain relief since they compete with buprenorphine at the mu receptor. Opioids with higher affinity for the mu receptor (morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl) may be more efficacious.

- Discontinue buprenorphine and treat the patient with scheduled full opioid analgesics, titrating the dose initially to try to avoid withdrawal and then to provide pain relief. The partial agonism of the mu-receptor from buprenorphine and the blockade of other opioids can persist for as long as 72 hours. During this period, close monitoring and keeping naloxone available are important. When acute pain resolves, discontinue full opioid agonist therapy and resume buprenorphine using an induction protocol.

For our clinical example, we recommend continuing buprenorphine at 16 mg daily, optimizing nonopioid treatment strategies, and using a higher dose parenteral full opioid agonist every 3 hours as needed to achieve adequate analgesia. The patient should be frequently monitored for adverse effects, and naloxone kept available. Full opioid analgesics should be tapered and discontinued as the acute pain resolves. The patient should be reassured that there is no evidence that using opioids to treat acute pain episodes increases the risk of relapse and that untreated acute pain is a more likely trigger for relapse. The patient’s buprenorphine provider should be contacted at admission to verify dose as well as at discharge.

DISCHARGE PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT

Early discharge planning is essential for appropriate and safe management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence. The major goals are to treat acute pain effectively, improve function, and return care to the patient’s usual treating physician or methadone clinic. Patients on chronic opioid therapy often have a written opioid treatment agreement specifying only 1 prescriber. Therefore, verbal communication with the patient’s authorized prescriber at admission and at discharge is essential, particularly given that the discharge summary may not be available at follow-up. Additional or higher doses of opioids should not be prescribed at discharge unless discussed with the patient’s authorized prescriber. If it is believed necessary to provide opioid medication at discharge it should only be provided for a short period: 3 to 7 days.35 Patients with OUD should be referred for addiction treatment, including MAT, and should be educated on harm-reduction strategies, including safe injecting, obtaining clean needles, and recognizing, avoiding, and treating opioid overdose. Prescribing intranasal naloxone should be strongly considered for patients with OUD and for patients who are taking more than 50 mg oral morphine equivalents for chronic pain.34

CONCLUSION

Management of acute pain in opioid-dependent patients is a complex and increasingly common problem encountered by hospitalists. In addition, given the OUD epidemic in the United States, safe opioid prescribing has become a paramount goal for all physicians. Although acute pain management will be individualized and will encompass clinical judgment, this review provides an evidence-based guide to effective and safe acute pain management and optimal opioid prescribing for hospitalized opioid-dependent patients.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats. Therapeutic drug use. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/faststats/drug-use-therapeutic.htm. Accessed August 23, 2016.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Latest Prescription Trends for Controlled Prescription Drugs. http://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/meetings-events/2015/09/latest-prescription-trends-controlled-prescription-drugs. Published September 1, 2015. Accessed August 23, 2016.

4. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple cause of death data. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed September 9, 2016.

6. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154-163. PubMed

7. American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. https://www.naabt.org/documents/APS_consenus_document.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed August 23, 2016.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):384-396. PubMed

10. McNicol E, Carr DB. Pharmacological treatment of pain. In: McCarberg B, Passik SD, eds. Expert Guide to Pain Management. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2005:145-178.

11. Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker, JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223-255. PubMed

12. Miguez G, Laborda MA, Miller RR. Classical conditioning and pain: conditioned analgesia and hyperalgesia. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2014;145:10-20. PubMed

13. Ewan EE, Martin TJ. Analgesics as reinforcers with chronic pain: evidence from operant studies. Neurosci Lett. 2013;557(pt A):60-64. PubMed

14. Mehta V, Langford R. Acute pain management in opioid dependent patients. Rev Pain. 2009;3(2):10-14. PubMed

15. Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1253-1263. PubMed

16. Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(1):299-343. PubMed

17. Ling GS, Paul D, Simantov R, Pasternak GW. Differential development of acute tolerance to analgesia, respiratory depression, gastrointestinal transit and hormone release in a morphine infusion model. Life Sci. 1989;45(18):1627-1636. PubMed

18. Pattinson KT. Opioids and the control of respiration. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(6):747-758. PubMed

19. Hagemeier NE, Gray JA, Pack RP. Prescription drug abuse: a comparison of prescriber and pharmacist perspectives. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):761-768. PubMed

20. Drug Enforcement Administration, US Department of Justice. National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary. Washington, DC: Drug Enforcement Administration, US Dept of Justice; 2015. DEA intelligence report DEA-DCT-DIR-039-15.

21. Laroche F, Rostaing S, Aubrun F, Perrot S. Pain management in heroin and cocaine users. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(5):446-450. PubMed

22. Savage SR, Schofferman J. Pharmacological therapies of pain in drug and alcohol addictions. In: Miller N, Gold M, eds. Pharmacological Therapies for Drug and Alcohol Addictions. New York, NY: Dekker; 1995:373-409.

23. Vadivelu N, Lumermann L, Zhu R, Kodumudi G, Elhassan AO, Kaye AD. Pain control in the presence of drug addiction. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(5):35. PubMed

24. Johns AR, Gossop M. Prescribing methadone for the opiate addict: a problem of dosage conversion. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;16(1):61-66. PubMed

25. Halbsguth U, Rentsch KM, Eich-Höchli D, Diterich I, Fattinger K. Oral diacetylmorphine (heroin) yields greater morphine bioavailability than oral morphine: bioavailability related to dosage and prior opioid exposure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(6):781-791. PubMed

26. Milone MC. Laboratory testing for prescription opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(4):408-416. PubMed

27. Huxtable CA, Roberts LJ, Somogyi AA, MacIntyre PE. Acute pain management in opioid-tolerant patients: a growing challenge. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(5):804-823. PubMed

28. George JA, Lin EE, Hanna MN, et al. The effect of intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia with and without background infusion on respiratory depression: a meta-analysis. J Opioid Manag. 2010;6(1):47-54. PubMed

29. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. PubMed

30. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):127-134. PubMed

31. Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(3):269-276. PubMed

32. Sen S, Arulkumar S, Cornett EM, et al. New pain management options for the surgical patient on methadone and buprenorphine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(3):16. PubMed

33. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. PubMed

34. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice—integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. PubMed

35. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. PubMed

Up to 40% of Americans experience chronic pain of some kind.1 In the United States, opioid analgesics are the most prescribed class of medications,2 with 245 million prescriptions filled in 2014 alone. Thirty-five percent of these prescriptions were for long-term therapy.3 It is now apparent that opioid pain medication use presents serious risks. In 2014, 10.3 million persons reported using prescription opioids for nonmedical reasons.4 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died of overdose related to opioid medication.5 In addition, heroin use in the United States has increased over the past decade.6 Opioid agonist maintenance therapy is also increasingly used to treat patients with opioid use disorder.

Given the prevalence of opioid use in the United States, it is important for hospitalists to be able to appropriately and safely manage acute pain in patients who have been exposed long-term to opioids, whether it is therapeutic or non-medical in origin. Although nonopioid medications and nondrug treatments are essential components of managing all acute pain, opioids continue to be the mainstay of treatment for severe acute pain in both opioid-naïve and opioid-dependent patients.

Given the paucity of published trials meeting the typical criteria, we did not perform a structured meta-analysis but, instead, a case-based narrative review of the relevant published literature. Our goal in performing this review is to guide hospitalists in the appropriate and safe use of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain in hospitalized patients who are opioid-dependent.

DEFINITIONS

When managing acute pain in patients with opioid dependence it is important to have a clear understanding of the definitions related to opioid use. Addiction, physical dependence and tolerance have been defined by a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, American Academy of Pain Medicine, and American Pain Society7: Addiction is a primary, chronic, biological disease, with genetic, psychosocial and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

Physical Dependence is a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

Tolerance is the state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress with symptoms including a strong desire for opioids, inability to control or reduce use of opioids, continued use despite adverse consequences, and development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Physical dependence and tolerance are common consequences of long-term opioid use. In contrast, OUD has been reported to affect only 2% to 6% of individuals exposed to opioids.9 The underlying mechanisms that lead an individual to abuse or become addicted to opioids largely due to the effects opioids have on endogenous μ-opioid receptors. As analgesics, opioids exert their effects by binding primarily to these μ-opioid receptors, with a large concentration in the brain regions regulating pain perception.10,11 There is also a large concentration of μ-opioid receptors in the brain reward regions, leading to perceptions of pleasure and euphoria. Repeated administration of opioids conditions the brain to a learned association between receiving the opiate and euphoria.12,13 This association becomes stronger as the frequency and duration of administration increases over time, ultimately leading to the desire or craving of the opioid’s effect.

The effect of tolerance also contributes to the pathophysiology of opioid abuse as it leads to a decrease in opioid potency with repeated administration.14-16 To achieve analgesia as well as the reward effect, opioid dosage and/or frequency must be increased, strengthening the association between receipt of opioid and reward. Tolerance to the reward effect occurs quickly, whereas tolerance to respiratory depression occurs much more slowly.17 This mismatch in tolerance of effect may lead to increase in opioid doses to maintain analgesia or euphoria, and also places patients at a higher risk of overdose.18

ACUTE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Clinical Example: Heroin User

A 47-year-old man is admitted with fever, chills, and severe mid-back pain and receives a diagnosis of sepsis. The patient admits to using intravenous heroin 500 mg (five 100 mg “bags”) on a daily basis. He is admitted, fluid resuscitated and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Blood cultures quickly grow Staphylococcus aureus. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine shows cervical vertebral osteomyelitis. On examination, the patient is diaphoretic and complains of diffuse myalgias and diarrhea. The patient’s back pain is so severe that he cannot ambulate. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

Managing acute pain in a patient using heroin can be challenging for many reasons. First, both physicians and pharmacists report a lack of confidence in their ability to prescribe opioids safely or to treat patients with a history of opioid abuse.19 Second, there is a paucity of evidence in treating acute pain in heroin users. Finally, due to the clandestine manufacturing of illicit drugs, the actual purity of the drug is often unknown making it difficult to assess the dose of opioids in heroin users. Drug Enforcement Agency seizure data indicate a wide range of heroin purity: 30% to 70%.20

In the hospital setting, acute pain is often undertreated in patients with a history of active opioid abuse. This may be due to providers’ misconceptions regarding pain and behavior in opioid addicts, including worrying that the patient’s pain is exaggerated in order to obtain drugs, thinking that a regular opioid habit eliminates pain, believing that opioid therapy is not effective in drug addicts, or worrying that prescribing opioids will exacerbate drug addiction.21 Data demonstrates that the presence of opioid addiction seems to worsen the experience of acute pain.22 These patients also often have a higher tolerance and thus require higher dosages and more frequent dosing of opioids to adequately treat their pain.23

Converting daily heroin use to morphine equivalents is necessary to establish a baseline analgesic requirement and to prevent withdrawal. It is challenging to convert illicit heroin to morphine equivalents however, as one must take into account the wide variation in purity and understand that the stated use of heroin (e.g. 500 mg daily) reflects weight and not dosage of heroin.20

In these patients, treatment of acute pain should be individualized according to presenting illness and comorbidities. Previous data and an average purity of 40% suggest that the parenteral morphine equivalent to a bag of heroin (100 mg) is 15 to 30 mg.20,24,25 Common equianalgesic doses of opioid medications are listed in Table 1. Because of increased tolerance, the frequency of administration should be shortened, from every 4 hours to every 2 or 3 hours. Except for a shorter onset of action, there has not been a difference shown in superiority between oral and parenteral routes of administration. Finally, patients should receive both long-acting basal and short-acting as-needed analgesics based on their daily use of opioids.23

In our clinical example, IV heroin 500 mg daily converts to parenteral morphine 75 to 150 mg every 24 hours. We recommend initiating IV morphine 10 mg every 3 hours as needed for pain and withdrawal symptoms, with early reassessment regarding need for a higher dose or a shorter frequency based on symptoms. Nonopioid analgesics should also be administered with the goal of decreasing the opioid requirement. As soon as possible, the patient should be changed to oral basal and short-acting opioids as needed for breakthrough pain. The appropriate dose of long acting basal analgesia can be determined the following day based on the patient’s total daily dose (TDD) of opioids. An example of converting from intravenous PRN morphine to oral basal and short acting opioids is shown in Table 2.

In communicating with a patient with opioid-use disorder with acute pain, it is best to outline the pain management plan at admission including: the plan to effectively treat the patient’s acute pain, prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms, change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible, discussion of non-opioid and non-drug treatments, reinforcement that opioids will be tapered as the acute pain episode resolves, and a detailed plan for discharge Later in this article, we describe discharge planning.

Clinical Example: Patient on Chronic Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

A 64 year-old man was involved in a motorcycle accident and suffered a right distal tibia-fibula fracture and several broken ribs with a secondary pneumothorax. The patient’s past medical history is significant for chronic low back pain for which he states he takes morphine sustained release 30 mg orally every 8 hours and morphine immediate release 15 mg orally four times daily for breakthrough pain. The patient states his pain is much worse than prior to the accident. Trauma surgery requests recommendations on appropriate pain management. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

When treating acute pain in patients with chronic pain on opioid therapy, it is vital to establish the patient’s baseline pain level and to accurately reconcile the patient’s outpatient daily opioid use. The patient’s prescription record should be verified in the state’s prescription drug monitoring program. On admission, a urine drug test should be obtained to assess for use of other potential illicit substances (eg, cocaine). Patients who test positive for illicit substances are at high risk for a substance use disorder. Management and discharge plans should be as outlined in the above case. It is important to know that the first-tier immunoassay urine toxicology screens used by hospitals test for natural opioids (morphine, codeine, heroin). Semi-synthetic (example, oxycodone) or synthetic (example, fentanyl) opioids are unlikely to be detected and thus the urine drug screen may not be helpful to determine adherence to certain prescription opioids. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry is the most sensitive and specific type of urine screen and can be ordered to confirm a prescribed opioid if needed.26

Pain management should begin with calculating the TDD of oral opioids that the patient was taking prior to admission, and converting to morphine equivalents. For moderate acute pain, TDD can be increased by 25% to 50%. The revised TDD can then be prescribed as a long-acting opioid every 8 to 12 hours to provide basal analgesia. The dose of additional immediate-release medication available throughout the day to manage breakthrough pain is determined by dividing the new TDD into every 3 to 4 hours as-needed dosing (Table 2).

If severe pain is anticipated, patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is an effective alternative to deliver opioids. The use of PCA allows self-titration, on demand analgesia, and minimizes the likelihood of under-dosing the patient.27 The revised TDD is a useful starting point when calculating the PCA dosage regimen. Ideally, the revised TDD should be prescribed as a long acting oral opioid medication every 8 to 12 hours for basal analgesia, with PCA administered as an as-needed bolus. If a patient cannot tolerate oral medications, PCA can provide continuous infusion of medication to provide basal analgesia, though the risk of oversedation and respiratory depression is increased.28

For our clinical example, we recommend increasing the preadmission TDD of opioids (180 mg morphine equivalents) by 25% (225 mg) and administering as morphine 75 mg sustained-release every 8 hours to provide baseline analgesia and prevent withdrawal symptoms. The acute pain can be managed by initiating morphine PCA without continuous infusion at 0.5 mg bolus every 8 minutes as needed for breakthrough pain or oral morphine 30 mg immediate-release tablets every 3 hours as needed for pain. The patient should be assessed frequently, and naloxone kept readily available. In addition, nonopioid and nondrug treatments should be optimized.

When communicating with patients with underlying chronic pain on chronic opioid therapy, it is important to discuss the treatment plan early, including addressing that they will likely not be pain free during their hospitalization, but rather goals of pain relief and improved function should be established. The plan to change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible and importance of multi-modal treatment should be emphasized. The patient should be informed that medication changes are for the short-term only and that the underlying chronic pain will likely remain unchanged.

Clinical Example: Patient on Medication-Assisted Therapy

A 42-year-old woman presents with acute epigastric pain and receives a diagnosis of acute gallstone pancreatitis. She states that her pain is very severe and appears uncomfortable. Her past medical history is significant for heroin addiction, but she has been successfully treated for opioid-use disorder with buprenorphine 16 mg daily for the past three years. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with her about her pain management?

Medication-assisted therapies (MATs) for treatment of opioid abuse, which include methadone and buprenorphine (Table 3), have been shown to be effective in helping patients recover in opioid-use disorder, are cost-effective and reduce the risk of opioid overdose.29 However, treatment for acute pain in patients who are receiving methadone or buprenorphine MAT is a challenge because of pharmacokinetic changes that occur with prolonged use. It is important to know that patients receiving opioid agonist MAT are usually treated with 1 dose every 24 to 48 hours and do not receive sustained analgesia.30

In the case of patients on methadone as MAT, the methadone should be continued at the prescribed daily dose and additional short-acting opioid analgesics given to provide appropriate pain relief.27,31 Because of opioid tolerance, patients receiving MAT often require increased and more frequent doses of short-acting opioid analgesics to achieve adequate pain control.

Buprenorphine is a mu-opioid receptor partial agonist. The partial agonist properties of buprenorphine result in a “ceiling effect” that limits maximal analgesic and euphoric potential. Buprenorphine’s high affinity for the mu receptor also may result in competition with full opioid agonist analgesics, creating a challenge in treating acute pain. Because of the erratic dissociation of buprenorphine from the mu receptor, naloxone should be available and patients should be frequently monitored when the two agents are administered together. Recommendations regarding acute pain management in patients being treated with buprenorphine are largely based on expert opinion. Treatment options include32-34:

- Continue maintenance therapy with buprenorphine and treat acute pain with short acting opioid agonists. Higher doses of opioid agonists and more frequent dosing may be needed to provide adequate pain relief since they compete with buprenorphine at the mu receptor. Opioids with higher affinity for the mu receptor (morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl) may be more efficacious.

- Discontinue buprenorphine and treat the patient with scheduled full opioid analgesics, titrating the dose initially to try to avoid withdrawal and then to provide pain relief. The partial agonism of the mu-receptor from buprenorphine and the blockade of other opioids can persist for as long as 72 hours. During this period, close monitoring and keeping naloxone available are important. When acute pain resolves, discontinue full opioid agonist therapy and resume buprenorphine using an induction protocol.

For our clinical example, we recommend continuing buprenorphine at 16 mg daily, optimizing nonopioid treatment strategies, and using a higher dose parenteral full opioid agonist every 3 hours as needed to achieve adequate analgesia. The patient should be frequently monitored for adverse effects, and naloxone kept available. Full opioid analgesics should be tapered and discontinued as the acute pain resolves. The patient should be reassured that there is no evidence that using opioids to treat acute pain episodes increases the risk of relapse and that untreated acute pain is a more likely trigger for relapse. The patient’s buprenorphine provider should be contacted at admission to verify dose as well as at discharge.

DISCHARGE PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT

Early discharge planning is essential for appropriate and safe management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence. The major goals are to treat acute pain effectively, improve function, and return care to the patient’s usual treating physician or methadone clinic. Patients on chronic opioid therapy often have a written opioid treatment agreement specifying only 1 prescriber. Therefore, verbal communication with the patient’s authorized prescriber at admission and at discharge is essential, particularly given that the discharge summary may not be available at follow-up. Additional or higher doses of opioids should not be prescribed at discharge unless discussed with the patient’s authorized prescriber. If it is believed necessary to provide opioid medication at discharge it should only be provided for a short period: 3 to 7 days.35 Patients with OUD should be referred for addiction treatment, including MAT, and should be educated on harm-reduction strategies, including safe injecting, obtaining clean needles, and recognizing, avoiding, and treating opioid overdose. Prescribing intranasal naloxone should be strongly considered for patients with OUD and for patients who are taking more than 50 mg oral morphine equivalents for chronic pain.34

CONCLUSION

Management of acute pain in opioid-dependent patients is a complex and increasingly common problem encountered by hospitalists. In addition, given the OUD epidemic in the United States, safe opioid prescribing has become a paramount goal for all physicians. Although acute pain management will be individualized and will encompass clinical judgment, this review provides an evidence-based guide to effective and safe acute pain management and optimal opioid prescribing for hospitalized opioid-dependent patients.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Up to 40% of Americans experience chronic pain of some kind.1 In the United States, opioid analgesics are the most prescribed class of medications,2 with 245 million prescriptions filled in 2014 alone. Thirty-five percent of these prescriptions were for long-term therapy.3 It is now apparent that opioid pain medication use presents serious risks. In 2014, 10.3 million persons reported using prescription opioids for nonmedical reasons.4 Between 1999 and 2014, more than 165,000 people in the United States died of overdose related to opioid medication.5 In addition, heroin use in the United States has increased over the past decade.6 Opioid agonist maintenance therapy is also increasingly used to treat patients with opioid use disorder.

Given the prevalence of opioid use in the United States, it is important for hospitalists to be able to appropriately and safely manage acute pain in patients who have been exposed long-term to opioids, whether it is therapeutic or non-medical in origin. Although nonopioid medications and nondrug treatments are essential components of managing all acute pain, opioids continue to be the mainstay of treatment for severe acute pain in both opioid-naïve and opioid-dependent patients.

Given the paucity of published trials meeting the typical criteria, we did not perform a structured meta-analysis but, instead, a case-based narrative review of the relevant published literature. Our goal in performing this review is to guide hospitalists in the appropriate and safe use of opioid analgesics in treating acute pain in hospitalized patients who are opioid-dependent.

DEFINITIONS

When managing acute pain in patients with opioid dependence it is important to have a clear understanding of the definitions related to opioid use. Addiction, physical dependence and tolerance have been defined by a joint consensus statement of the American Society of Addiction Medicine, American Academy of Pain Medicine, and American Pain Society7: Addiction is a primary, chronic, biological disease, with genetic, psychosocial and environmental factors influencing its development and manifestations. It is characterized by behaviors that include one or more of the following: impaired control over drug use, compulsive use, continued use despite harm, and craving.

Physical Dependence is a state of adaptation that is manifested by a drug class specific withdrawal syndrome that can be produced by abrupt cessation, rapid dose reduction, decreasing blood level of the drug, and/or administration of an antagonist.

Tolerance is the state of adaptation in which exposure to a drug induces changes that result in a diminution of one or more of the drug’s effects over time.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is defined as a problematic pattern of opioid use leading to clinically significant impairment or distress with symptoms including a strong desire for opioids, inability to control or reduce use of opioids, continued use despite adverse consequences, and development of tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.8

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Physical dependence and tolerance are common consequences of long-term opioid use. In contrast, OUD has been reported to affect only 2% to 6% of individuals exposed to opioids.9 The underlying mechanisms that lead an individual to abuse or become addicted to opioids largely due to the effects opioids have on endogenous μ-opioid receptors. As analgesics, opioids exert their effects by binding primarily to these μ-opioid receptors, with a large concentration in the brain regions regulating pain perception.10,11 There is also a large concentration of μ-opioid receptors in the brain reward regions, leading to perceptions of pleasure and euphoria. Repeated administration of opioids conditions the brain to a learned association between receiving the opiate and euphoria.12,13 This association becomes stronger as the frequency and duration of administration increases over time, ultimately leading to the desire or craving of the opioid’s effect.

The effect of tolerance also contributes to the pathophysiology of opioid abuse as it leads to a decrease in opioid potency with repeated administration.14-16 To achieve analgesia as well as the reward effect, opioid dosage and/or frequency must be increased, strengthening the association between receipt of opioid and reward. Tolerance to the reward effect occurs quickly, whereas tolerance to respiratory depression occurs much more slowly.17 This mismatch in tolerance of effect may lead to increase in opioid doses to maintain analgesia or euphoria, and also places patients at a higher risk of overdose.18

ACUTE PAIN MANAGEMENT

Clinical Example: Heroin User

A 47-year-old man is admitted with fever, chills, and severe mid-back pain and receives a diagnosis of sepsis. The patient admits to using intravenous heroin 500 mg (five 100 mg “bags”) on a daily basis. He is admitted, fluid resuscitated and started on broad spectrum antibiotics. Blood cultures quickly grow Staphylococcus aureus. Magnetic resonance imaging of the spine shows cervical vertebral osteomyelitis. On examination, the patient is diaphoretic and complains of diffuse myalgias and diarrhea. The patient’s back pain is so severe that he cannot ambulate. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

Managing acute pain in a patient using heroin can be challenging for many reasons. First, both physicians and pharmacists report a lack of confidence in their ability to prescribe opioids safely or to treat patients with a history of opioid abuse.19 Second, there is a paucity of evidence in treating acute pain in heroin users. Finally, due to the clandestine manufacturing of illicit drugs, the actual purity of the drug is often unknown making it difficult to assess the dose of opioids in heroin users. Drug Enforcement Agency seizure data indicate a wide range of heroin purity: 30% to 70%.20

In the hospital setting, acute pain is often undertreated in patients with a history of active opioid abuse. This may be due to providers’ misconceptions regarding pain and behavior in opioid addicts, including worrying that the patient’s pain is exaggerated in order to obtain drugs, thinking that a regular opioid habit eliminates pain, believing that opioid therapy is not effective in drug addicts, or worrying that prescribing opioids will exacerbate drug addiction.21 Data demonstrates that the presence of opioid addiction seems to worsen the experience of acute pain.22 These patients also often have a higher tolerance and thus require higher dosages and more frequent dosing of opioids to adequately treat their pain.23

Converting daily heroin use to morphine equivalents is necessary to establish a baseline analgesic requirement and to prevent withdrawal. It is challenging to convert illicit heroin to morphine equivalents however, as one must take into account the wide variation in purity and understand that the stated use of heroin (e.g. 500 mg daily) reflects weight and not dosage of heroin.20

In these patients, treatment of acute pain should be individualized according to presenting illness and comorbidities. Previous data and an average purity of 40% suggest that the parenteral morphine equivalent to a bag of heroin (100 mg) is 15 to 30 mg.20,24,25 Common equianalgesic doses of opioid medications are listed in Table 1. Because of increased tolerance, the frequency of administration should be shortened, from every 4 hours to every 2 or 3 hours. Except for a shorter onset of action, there has not been a difference shown in superiority between oral and parenteral routes of administration. Finally, patients should receive both long-acting basal and short-acting as-needed analgesics based on their daily use of opioids.23

In our clinical example, IV heroin 500 mg daily converts to parenteral morphine 75 to 150 mg every 24 hours. We recommend initiating IV morphine 10 mg every 3 hours as needed for pain and withdrawal symptoms, with early reassessment regarding need for a higher dose or a shorter frequency based on symptoms. Nonopioid analgesics should also be administered with the goal of decreasing the opioid requirement. As soon as possible, the patient should be changed to oral basal and short-acting opioids as needed for breakthrough pain. The appropriate dose of long acting basal analgesia can be determined the following day based on the patient’s total daily dose (TDD) of opioids. An example of converting from intravenous PRN morphine to oral basal and short acting opioids is shown in Table 2.

In communicating with a patient with opioid-use disorder with acute pain, it is best to outline the pain management plan at admission including: the plan to effectively treat the patient’s acute pain, prevent opioid withdrawal symptoms, change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible, discussion of non-opioid and non-drug treatments, reinforcement that opioids will be tapered as the acute pain episode resolves, and a detailed plan for discharge Later in this article, we describe discharge planning.

Clinical Example: Patient on Chronic Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain

A 64 year-old man was involved in a motorcycle accident and suffered a right distal tibia-fibula fracture and several broken ribs with a secondary pneumothorax. The patient’s past medical history is significant for chronic low back pain for which he states he takes morphine sustained release 30 mg orally every 8 hours and morphine immediate release 15 mg orally four times daily for breakthrough pain. The patient states his pain is much worse than prior to the accident. Trauma surgery requests recommendations on appropriate pain management. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with him about his pain management?

When treating acute pain in patients with chronic pain on opioid therapy, it is vital to establish the patient’s baseline pain level and to accurately reconcile the patient’s outpatient daily opioid use. The patient’s prescription record should be verified in the state’s prescription drug monitoring program. On admission, a urine drug test should be obtained to assess for use of other potential illicit substances (eg, cocaine). Patients who test positive for illicit substances are at high risk for a substance use disorder. Management and discharge plans should be as outlined in the above case. It is important to know that the first-tier immunoassay urine toxicology screens used by hospitals test for natural opioids (morphine, codeine, heroin). Semi-synthetic (example, oxycodone) or synthetic (example, fentanyl) opioids are unlikely to be detected and thus the urine drug screen may not be helpful to determine adherence to certain prescription opioids. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry is the most sensitive and specific type of urine screen and can be ordered to confirm a prescribed opioid if needed.26

Pain management should begin with calculating the TDD of oral opioids that the patient was taking prior to admission, and converting to morphine equivalents. For moderate acute pain, TDD can be increased by 25% to 50%. The revised TDD can then be prescribed as a long-acting opioid every 8 to 12 hours to provide basal analgesia. The dose of additional immediate-release medication available throughout the day to manage breakthrough pain is determined by dividing the new TDD into every 3 to 4 hours as-needed dosing (Table 2).

If severe pain is anticipated, patient controlled analgesia (PCA) is an effective alternative to deliver opioids. The use of PCA allows self-titration, on demand analgesia, and minimizes the likelihood of under-dosing the patient.27 The revised TDD is a useful starting point when calculating the PCA dosage regimen. Ideally, the revised TDD should be prescribed as a long acting oral opioid medication every 8 to 12 hours for basal analgesia, with PCA administered as an as-needed bolus. If a patient cannot tolerate oral medications, PCA can provide continuous infusion of medication to provide basal analgesia, though the risk of oversedation and respiratory depression is increased.28

For our clinical example, we recommend increasing the preadmission TDD of opioids (180 mg morphine equivalents) by 25% (225 mg) and administering as morphine 75 mg sustained-release every 8 hours to provide baseline analgesia and prevent withdrawal symptoms. The acute pain can be managed by initiating morphine PCA without continuous infusion at 0.5 mg bolus every 8 minutes as needed for breakthrough pain or oral morphine 30 mg immediate-release tablets every 3 hours as needed for pain. The patient should be assessed frequently, and naloxone kept readily available. In addition, nonopioid and nondrug treatments should be optimized.

When communicating with patients with underlying chronic pain on chronic opioid therapy, it is important to discuss the treatment plan early, including addressing that they will likely not be pain free during their hospitalization, but rather goals of pain relief and improved function should be established. The plan to change to oral opioid analgesics as soon as possible and importance of multi-modal treatment should be emphasized. The patient should be informed that medication changes are for the short-term only and that the underlying chronic pain will likely remain unchanged.

Clinical Example: Patient on Medication-Assisted Therapy

A 42-year-old woman presents with acute epigastric pain and receives a diagnosis of acute gallstone pancreatitis. She states that her pain is very severe and appears uncomfortable. Her past medical history is significant for heroin addiction, but she has been successfully treated for opioid-use disorder with buprenorphine 16 mg daily for the past three years. What is the best way to manage this patient’s acute pain and communicate with her about her pain management?

Medication-assisted therapies (MATs) for treatment of opioid abuse, which include methadone and buprenorphine (Table 3), have been shown to be effective in helping patients recover in opioid-use disorder, are cost-effective and reduce the risk of opioid overdose.29 However, treatment for acute pain in patients who are receiving methadone or buprenorphine MAT is a challenge because of pharmacokinetic changes that occur with prolonged use. It is important to know that patients receiving opioid agonist MAT are usually treated with 1 dose every 24 to 48 hours and do not receive sustained analgesia.30

In the case of patients on methadone as MAT, the methadone should be continued at the prescribed daily dose and additional short-acting opioid analgesics given to provide appropriate pain relief.27,31 Because of opioid tolerance, patients receiving MAT often require increased and more frequent doses of short-acting opioid analgesics to achieve adequate pain control.

Buprenorphine is a mu-opioid receptor partial agonist. The partial agonist properties of buprenorphine result in a “ceiling effect” that limits maximal analgesic and euphoric potential. Buprenorphine’s high affinity for the mu receptor also may result in competition with full opioid agonist analgesics, creating a challenge in treating acute pain. Because of the erratic dissociation of buprenorphine from the mu receptor, naloxone should be available and patients should be frequently monitored when the two agents are administered together. Recommendations regarding acute pain management in patients being treated with buprenorphine are largely based on expert opinion. Treatment options include32-34:

- Continue maintenance therapy with buprenorphine and treat acute pain with short acting opioid agonists. Higher doses of opioid agonists and more frequent dosing may be needed to provide adequate pain relief since they compete with buprenorphine at the mu receptor. Opioids with higher affinity for the mu receptor (morphine, hydromorphone, fentanyl) may be more efficacious.

- Discontinue buprenorphine and treat the patient with scheduled full opioid analgesics, titrating the dose initially to try to avoid withdrawal and then to provide pain relief. The partial agonism of the mu-receptor from buprenorphine and the blockade of other opioids can persist for as long as 72 hours. During this period, close monitoring and keeping naloxone available are important. When acute pain resolves, discontinue full opioid agonist therapy and resume buprenorphine using an induction protocol.

For our clinical example, we recommend continuing buprenorphine at 16 mg daily, optimizing nonopioid treatment strategies, and using a higher dose parenteral full opioid agonist every 3 hours as needed to achieve adequate analgesia. The patient should be frequently monitored for adverse effects, and naloxone kept available. Full opioid analgesics should be tapered and discontinued as the acute pain resolves. The patient should be reassured that there is no evidence that using opioids to treat acute pain episodes increases the risk of relapse and that untreated acute pain is a more likely trigger for relapse. The patient’s buprenorphine provider should be contacted at admission to verify dose as well as at discharge.

DISCHARGE PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT

Early discharge planning is essential for appropriate and safe management of acute pain in hospitalized patients with opioid dependence. The major goals are to treat acute pain effectively, improve function, and return care to the patient’s usual treating physician or methadone clinic. Patients on chronic opioid therapy often have a written opioid treatment agreement specifying only 1 prescriber. Therefore, verbal communication with the patient’s authorized prescriber at admission and at discharge is essential, particularly given that the discharge summary may not be available at follow-up. Additional or higher doses of opioids should not be prescribed at discharge unless discussed with the patient’s authorized prescriber. If it is believed necessary to provide opioid medication at discharge it should only be provided for a short period: 3 to 7 days.35 Patients with OUD should be referred for addiction treatment, including MAT, and should be educated on harm-reduction strategies, including safe injecting, obtaining clean needles, and recognizing, avoiding, and treating opioid overdose. Prescribing intranasal naloxone should be strongly considered for patients with OUD and for patients who are taking more than 50 mg oral morphine equivalents for chronic pain.34

CONCLUSION

Management of acute pain in opioid-dependent patients is a complex and increasingly common problem encountered by hospitalists. In addition, given the OUD epidemic in the United States, safe opioid prescribing has become a paramount goal for all physicians. Although acute pain management will be individualized and will encompass clinical judgment, this review provides an evidence-based guide to effective and safe acute pain management and optimal opioid prescribing for hospitalized opioid-dependent patients.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats. Therapeutic drug use. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/faststats/drug-use-therapeutic.htm. Accessed August 23, 2016.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Latest Prescription Trends for Controlled Prescription Drugs. http://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/meetings-events/2015/09/latest-prescription-trends-controlled-prescription-drugs. Published September 1, 2015. Accessed August 23, 2016.

4. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple cause of death data. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed September 9, 2016.

6. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154-163. PubMed

7. American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. https://www.naabt.org/documents/APS_consenus_document.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed August 23, 2016.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):384-396. PubMed

10. McNicol E, Carr DB. Pharmacological treatment of pain. In: McCarberg B, Passik SD, eds. Expert Guide to Pain Management. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2005:145-178.

11. Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker, JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223-255. PubMed

12. Miguez G, Laborda MA, Miller RR. Classical conditioning and pain: conditioned analgesia and hyperalgesia. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2014;145:10-20. PubMed

13. Ewan EE, Martin TJ. Analgesics as reinforcers with chronic pain: evidence from operant studies. Neurosci Lett. 2013;557(pt A):60-64. PubMed

14. Mehta V, Langford R. Acute pain management in opioid dependent patients. Rev Pain. 2009;3(2):10-14. PubMed

15. Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1253-1263. PubMed

16. Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(1):299-343. PubMed

17. Ling GS, Paul D, Simantov R, Pasternak GW. Differential development of acute tolerance to analgesia, respiratory depression, gastrointestinal transit and hormone release in a morphine infusion model. Life Sci. 1989;45(18):1627-1636. PubMed

18. Pattinson KT. Opioids and the control of respiration. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(6):747-758. PubMed

19. Hagemeier NE, Gray JA, Pack RP. Prescription drug abuse: a comparison of prescriber and pharmacist perspectives. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):761-768. PubMed

20. Drug Enforcement Administration, US Department of Justice. National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary. Washington, DC: Drug Enforcement Administration, US Dept of Justice; 2015. DEA intelligence report DEA-DCT-DIR-039-15.

21. Laroche F, Rostaing S, Aubrun F, Perrot S. Pain management in heroin and cocaine users. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(5):446-450. PubMed

22. Savage SR, Schofferman J. Pharmacological therapies of pain in drug and alcohol addictions. In: Miller N, Gold M, eds. Pharmacological Therapies for Drug and Alcohol Addictions. New York, NY: Dekker; 1995:373-409.

23. Vadivelu N, Lumermann L, Zhu R, Kodumudi G, Elhassan AO, Kaye AD. Pain control in the presence of drug addiction. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(5):35. PubMed

24. Johns AR, Gossop M. Prescribing methadone for the opiate addict: a problem of dosage conversion. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;16(1):61-66. PubMed

25. Halbsguth U, Rentsch KM, Eich-Höchli D, Diterich I, Fattinger K. Oral diacetylmorphine (heroin) yields greater morphine bioavailability than oral morphine: bioavailability related to dosage and prior opioid exposure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(6):781-791. PubMed

26. Milone MC. Laboratory testing for prescription opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(4):408-416. PubMed

27. Huxtable CA, Roberts LJ, Somogyi AA, MacIntyre PE. Acute pain management in opioid-tolerant patients: a growing challenge. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(5):804-823. PubMed

28. George JA, Lin EE, Hanna MN, et al. The effect of intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia with and without background infusion on respiratory depression: a meta-analysis. J Opioid Manag. 2010;6(1):47-54. PubMed

29. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. PubMed

30. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):127-134. PubMed

31. Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(3):269-276. PubMed

32. Sen S, Arulkumar S, Cornett EM, et al. New pain management options for the surgical patient on methadone and buprenorphine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(3):16. PubMed

33. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. PubMed

34. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice—integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. PubMed

35. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. PubMed

1. Institute of Medicine. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education and Research. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. PubMed

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FastStats. Therapeutic drug use. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/faststats/drug-use-therapeutic.htm. Accessed August 23, 2016.

3. National Institute on Drug Abuse. The Latest Prescription Trends for Controlled Prescription Drugs. http://www.drugabuse.gov/news-events/meetings-events/2015/09/latest-prescription-trends-controlled-prescription-drugs. Published September 1, 2015. Accessed August 23, 2016.

4. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multiple cause of death data. https://wonder.cdc.gov/mcd.html. Accessed September 9, 2016.

6. Compton WM, Jones CM, Baldwin GT. Relationship between nonmedical prescription-opioid use and heroin use. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(2):154-163. PubMed

7. American Academy of Pain Medicine, American Pain Society, American Society of Addiction Medicine. https://www.naabt.org/documents/APS_consenus_document.pdf. Published 2001. Accessed August 23, 2016.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154(2):384-396. PubMed

10. McNicol E, Carr DB. Pharmacological treatment of pain. In: McCarberg B, Passik SD, eds. Expert Guide to Pain Management. Philadelphia, PA: American College of Physicians; 2005:145-178.

11. Akil H, Watson SJ, Young E, Lewis ME, Khachaturian H, Walker, JM. Endogenous opioids: biology and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:223-255. PubMed

12. Miguez G, Laborda MA, Miller RR. Classical conditioning and pain: conditioned analgesia and hyperalgesia. Acta Psychol (Amst). 2014;145:10-20. PubMed

13. Ewan EE, Martin TJ. Analgesics as reinforcers with chronic pain: evidence from operant studies. Neurosci Lett. 2013;557(pt A):60-64. PubMed

14. Mehta V, Langford R. Acute pain management in opioid dependent patients. Rev Pain. 2009;3(2):10-14. PubMed

15. Volkow ND, McLellan AT. Opioid abuse in chronic pain—misconceptions and mitigation strategies. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(13):1253-1263. PubMed

16. Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81(1):299-343. PubMed

17. Ling GS, Paul D, Simantov R, Pasternak GW. Differential development of acute tolerance to analgesia, respiratory depression, gastrointestinal transit and hormone release in a morphine infusion model. Life Sci. 1989;45(18):1627-1636. PubMed

18. Pattinson KT. Opioids and the control of respiration. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100(6):747-758. PubMed

19. Hagemeier NE, Gray JA, Pack RP. Prescription drug abuse: a comparison of prescriber and pharmacist perspectives. Subst Use Misuse. 2013;48(9):761-768. PubMed

20. Drug Enforcement Administration, US Department of Justice. National Heroin Threat Assessment Summary. Washington, DC: Drug Enforcement Administration, US Dept of Justice; 2015. DEA intelligence report DEA-DCT-DIR-039-15.

21. Laroche F, Rostaing S, Aubrun F, Perrot S. Pain management in heroin and cocaine users. Joint Bone Spine. 2012;79(5):446-450. PubMed

22. Savage SR, Schofferman J. Pharmacological therapies of pain in drug and alcohol addictions. In: Miller N, Gold M, eds. Pharmacological Therapies for Drug and Alcohol Addictions. New York, NY: Dekker; 1995:373-409.

23. Vadivelu N, Lumermann L, Zhu R, Kodumudi G, Elhassan AO, Kaye AD. Pain control in the presence of drug addiction. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(5):35. PubMed

24. Johns AR, Gossop M. Prescribing methadone for the opiate addict: a problem of dosage conversion. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1985;16(1):61-66. PubMed

25. Halbsguth U, Rentsch KM, Eich-Höchli D, Diterich I, Fattinger K. Oral diacetylmorphine (heroin) yields greater morphine bioavailability than oral morphine: bioavailability related to dosage and prior opioid exposure. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;66(6):781-791. PubMed

26. Milone MC. Laboratory testing for prescription opioids. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(4):408-416. PubMed

27. Huxtable CA, Roberts LJ, Somogyi AA, MacIntyre PE. Acute pain management in opioid-tolerant patients: a growing challenge. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(5):804-823. PubMed

28. George JA, Lin EE, Hanna MN, et al. The effect of intravenous opioid patient-controlled analgesia with and without background infusion on respiratory depression: a meta-analysis. J Opioid Manag. 2010;6(1):47-54. PubMed

29. Volkow ND, Frieden TR, Hyde PS, Cha SS. Medication-assisted therapies—tackling the opioid-overdose epidemic. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2063-2066. PubMed

30. Alford DP, Compton P, Samet JH. Acute pain management for patients receiving maintenance methadone or buprenorphine therapy. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(2):127-134. PubMed

31. Mehta V, Langford RM. Acute pain management for opioid dependent patients. Anaesthesia. 2006;61(3):269-276. PubMed

32. Sen S, Arulkumar S, Cornett EM, et al. New pain management options for the surgical patient on methadone and buprenorphine. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016;20(3):16. PubMed

33. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. PubMed

34. Fanucchi L, Lofwall MR. Putting parity into practice—integrating opioid-use disorder treatment into the hospital setting. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(9):811-813. PubMed

35. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain—United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(1):1-49. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical patients

Deprived of alcohol while in the hospital, up to 80% of patients who are alcohol-dependent risk developing alcohol withdrawal syndrome,1 a potentially life-threatening condition. Clinicians should anticipate the syndrome and be ready to treat and prevent its complications.

Because alcoholism is common, nearly every provider will encounter its complications and withdrawal symptoms. Each year, an estimated 1.2 million hospital admissions are related to alcohol abuse, and about 500,000 episodes of withdrawal symptoms are severe enough to require clinical attention.1–3 Nearly 50% of patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome are middle-class, highly functional individuals, making withdrawal difficult to recognize.1

While acute trauma patients or those with alcohol withdrawal delirium are often admitted directly to an intensive care unit (ICU), many others are at risk for or develop alcohol withdrawal syndrome and are managed initially or wholly on the acute medical unit. While specific statistics have not been published on non-ICU patients with alcohol withdrawal syndrome, they are an important group of patients who need to be well managed to prevent the progression of alcohol withdrawal syndrome to alcohol withdrawal delirium, alcohol withdrawal-induced seizure, and other complications.

This article reviews how to identify and manage alcohol withdrawal symptoms in noncritical, acutely ill medical patients, with practical recommendations for diagnosis and management.

CAN LEAD TO DELIRIUM TREMENS

In people who are physiologically dependent on alcohol, symptoms of withdrawal usually occur after abrupt cessation.4 If not addressed early in the hospitalization, alcohol withdrawal syndrome can progress to alcohol withdrawal delirium (also known as delirium tremens or DTs), in which the mortality rate is 5% to 10%.5,6 Potential mechanisms of DTs include increased dopamine release and dopamine receptor activity, hypersensitivity to N-methyl-d-aspartate, and reduced levels of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).7

Long-term changes are thought to occur in neurons after repeated detoxification from alcohol, a phenomenon called “kindling.” After each detoxification, alcohol craving and obsessive thoughts increase,8 and subsequent episodes of alcohol withdrawal tend to be progressively worse.

Withdrawal symptoms

Alcohol withdrawal syndrome encompasses a spectrum of symptoms and conditions, from minor (eg, insomnia, tremulousness) to severe (seizures, DTs).2 The symptoms typically depend on the amount of alcohol consumed, the time since the last drink, and the number of previous detoxifications.9

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition,1 states that to establish a diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, a patient must meet four criteria:

- The patient must have ceased or reduced alcohol intake after heavy or prolonged use.

- Two or more of the following must develop within a few hours to a few days: autonomic hyperactivity (sweating or pulse greater than 100 beats per minute); increased hand tremor; insomnia; nausea or vomiting; transient visual, tactile, or auditory hallucinations or illusions; psychomotor agitation; anxiety; grand mal seizure.

- The above symptoms must cause significant distress or functional impairment.

- The symptoms must not be related to another medical condition.