User login

Update on feeding tubes: Indications and troubleshooting complications

Introduction

Gastroenterologists are in a unique position to manage individuals with feeding tubes as their training underscores principles in digestion, absorption, nutrition support, and enteral tube placement. Adequate management of individuals with feeding tubes and, importantly, the complications that arise from feeding tube use and placement require a basic understanding of intestinal anatomy and physiology. Therefore, gastroenterologists are well suited to both place and manage individuals with feeding tubes in the long term.

Indications for tube feeding

When deciding on the appropriate route for artificial nutrition support, the first decision to be made is enteral access versus parenteral nutrition support. Enteral nutrition confers multiple benefits, including preservation of the mucosal lining, reductions in complicated infections, decreased costs, and improved patient compliance. All attempts at adequate enteral access should be made before deciding on the use of parenteral nutrition. Following the clinical decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support and enteral access, the next common decision is the anticipated duration of nutrition support. Generally, the oral or nasal tubes are used for short durations (i.e., less than 4 weeks) with percutaneous placement into the stomach or small intestine for longer-term feeding (i.e., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy [PEJ]).

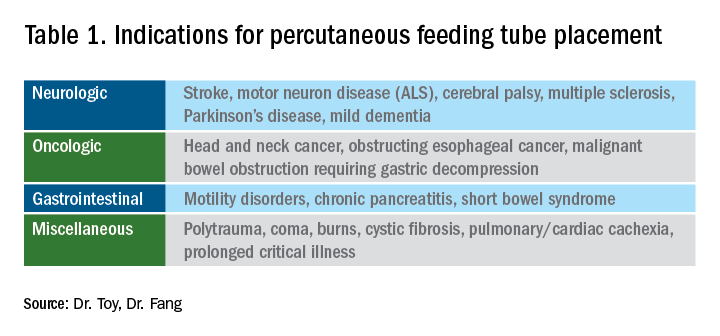

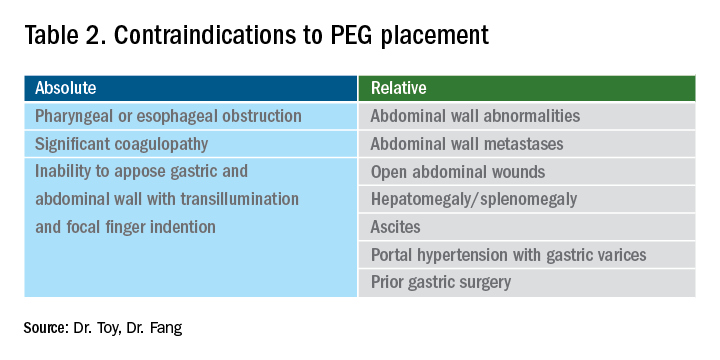

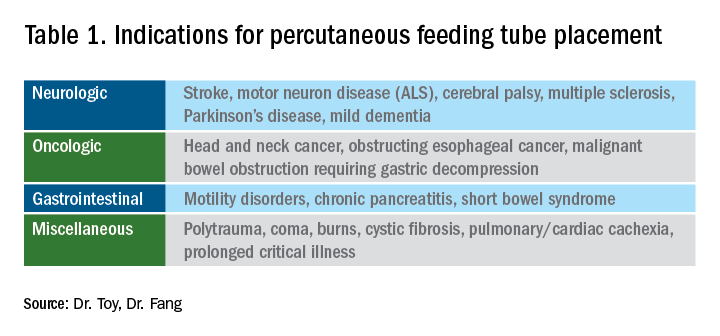

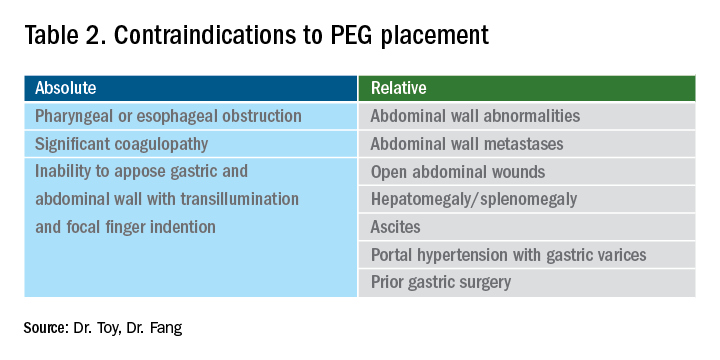

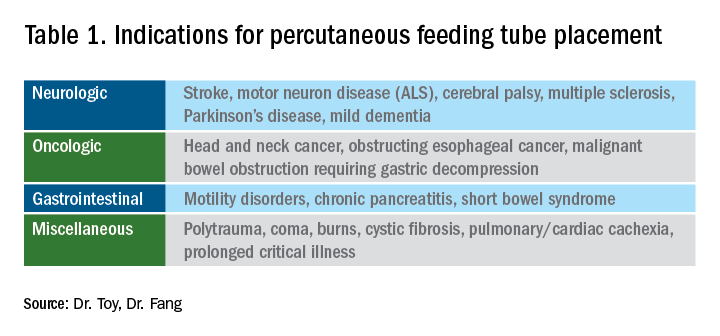

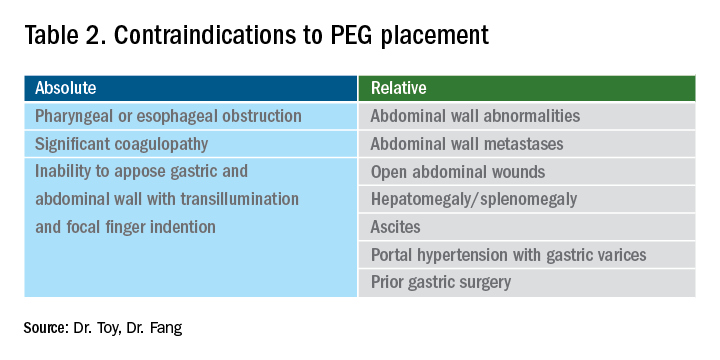

The most general indication for nutrition support is an inability to maintain adequate nutritional needs with oral intake alone. General categories of inadequate oral intake include neurologic disorders, malignancy, and gastrointestinal conditions affecting digestion and absorption (Table 1). Absolute and relative contraindications to PEG placement are listed in Table 2. If an endoscopic placement is not possible, alternative means of placement (i.e., surgery or interventional radiology) can be considered to avoid the consequences of prolonged malnutrition. In-hospital mortality following PEG placement has decreased 40% over the last 10 years, which can be attributed to improved patient selection, enhanced discharge practices, and exclusion of patients with the highest comorbidity and mortality rates, like those with advanced dementia or terminal cancer.1

PEG placement in patients with dementia is controversial, with previous studies not demonstrating improved outcomes and association with high mortality rates,2 so the practice is currently not recommended by the American Geriatrics Society in individuals with advanced dementia.3 However, a large Japanese study showed that careful selection of patients with mild dementia to undergo gastrostomy increased independence fourfold; therefore, multidisciplinary involvement is often necessary in the decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support in this population.4

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed additional strains on endoscopic placement and has highlighted the effect of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) on GI symptoms. A recent meta-analysis showed an overall incidence of GI symptoms of 17.6% in the following conditions in decreasing order of prevalence: anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort.5 In addition, the prolonged ventilatory requirements among a subset of individuals with the most severe COVID-19 results in extended periods of nutrition support via enteral tube placements. In individuals with ICU-acquired weakness and discharge to long-term care facilities, the placement of percutaneous endoscopic tubes may be required, although with the additional consideration of the need for an aerosolizing procedure. Delay of placement has been advocated, in addition to appropriate personal protective equipment, in order to ensure safe placement for the endoscopy staff.6

Types of feeding tubes

After deciding to feed a patient enterally and determining the anticipated duration of enteral support, the next decision is to determine the most appropriate location of feeding delivery: into the stomach or the small bowel. Gastric feeding is advantageous most commonly because of its increased capacity, allowing for larger volumes to be delivered over shorter durations. However, in the setting of postsurgical anatomy, gastroparesis, or obstructing tumors/pancreatic inflammation, distal delivery of tube feeds may be required into the jejunum. Additionally, percutaneous tubes placed into the stomach can have extenders into the small bowel (GJ tubes) to allow for feeding into the small bowel and decompression or delivery of medications into the stomach.

In general, gastric feeding is preferred over small bowel feeding as PEG tubes are more stable and have fewer complications than either PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Gastrostomy tubes are generally shorter and larger in diameter making them less likely to clog. PEG-J tubes have separate lumens for gastric and small intestinal access, but the smaller-bore jejunal extension tubes are more likely to clog or become dislodged. While direct PEJ is shown to have higher rates of tube patency and decreased rates of endoscopic re-intervention, compared with PEG-J,7 one limitation of a direct PEJ is difficulty in placement and site selection, which can be performed with a pediatric colonoscope or balloon enteroscopy system. Most commonly, this procedure is performed under general anesthesia.

In the case of a critically ill patient in the ICU, it is recommended to start enteral nutrition within 24-48 hours of arrival to avoid complications of prolonged calorie deficits. Nasally inserted feeding tubes (e.g., Cortrak, Avanos Medical Devices, Alpharetta, Ga.) are most commonly used at the bedside and can be placed blindly using electromagnetic image guidance, radiographically, or endoscopy. However, the small caliber of nasoenteric tubes comes with the common complication of clogging, which can be overcome with slightly larger bore gastric feeding tubes. If gastric feeding is not tolerated (e.g., in the case of vomiting, witnessed aspiration), small bowel feeding should be initiated and can be a more durable form of enteral feeding with fewer interruptions as feedings do not need to be held for procedures or symptomatic gastric intolerance. In clinical areas of question, or if there is a concern for intolerance of enteral feeding, a short trial with nasogastric or nasojejunal tube placement should be performed before a more definitive percutaneous placement.

With respect to percutaneous tubes, important characteristics to choose are the size (diameter in French units), type of internal retention device, and external appearance of the tube (standard or low profile). All percutaneous tubes contain an external retention device (i.e., bumper) that fits against the skin and an internal retention device that is either a balloon or plastic dome or funnel that prevents the tube from becoming dislodged. Balloon retention tubes require replacement every 3-6 months, while nonballoon tubes generally require replacement annually in order to prevent the plastic from cracking, which can make removal complicated. Low-profile tubes have an external cap, which, when opened, allows for extension tubing to be securely attached while in use and detached while not in use. Low-profile tubes are often preferred among younger, active patients and those with adequate dexterity to allow for attachment of the external extension tubing. These tubes are most often inserted as a replacement for an initially endoscopically placed tube, although one-step systems for initial placement are available. The size of the low-profile tube is chosen based on the size of the existing PEG tube and by measuring the length of the stoma tract using specialized measuring devices.8 Patients and caregivers can also be trained to replace balloon-type tubes on their own to limit complications of displaced or cracked tubes. Low-profile tubes are commercially available for both gastric placement and gastric placement with extension into the small bowel, which often requires fluoroscopy for secure placement.

All percutaneous enteral tubes are being transitioned to the ENfit connector system, which prevents connections from the enteral system to nonenteral systems (namely intravenous lines, chest tubes) and vice versa. Tubing misconnections have been rarely reported, and the EnFIT system is designed to prevent such misadventures that have resulted in serious complications and even mortality.9 Adapter devices are available that may be required for patients with feeding tubes who have not been transitioned yet. Most commonly with new tube placements and replacements, patients and providers will have to become familiar with the new syringes and feeding bags required with EnFIT connectors.

Gastrostomy placement can be considered a higher-risk endoscopic procedure. One complicating factor is the increased use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies in individuals with a history of neurologic insults. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines recommend that coumadin be held 5 days before the procedure and bridged with heparin if the patient is at high risk of thromboembolic complications. For patients on dual anti-platelet therapy, thienopyridines like clopidogrel are often stopped 5-7 days prior to procedure with continuation of aspirin,10 but there are more recent data that PEG insertion is safe with continued use of DAPT.11 Direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) are often stopped 24-48 hours prior to procedure and then restarted 48 hours after tube placement, but this is dependent on the half-life of the specific DOAC and the patient’s renal function. Patients with decreased creatinine clearance may need to hold the DOAC up to 3-4 days prior to the procedure. In this situation, referring to ASGE guidelines and consultation with a hematologist or managing anti-coagulation clinic is advised.10

Troubleshooting complications

Nasoenteric tubes: One of the most common and irritating complications with nasoenteric feeding tubes is clogging. To prevent clogging, the tube should be flushed frequently.12 At least 30 mL of free water should be used to flush the tube every 4-8 hours for continuous feedings or before and after bolus feeding. Additionally, 15-30 mL of water should be given with each separate medication administration, and if possible, medication administration via small-bore small bowel feeding tubes should be avoided.12 Water flushing is especially important with small-caliber tubes and pumps that deliver both feeding and water flushes. It is available for small bowel feeding in order to allow for programmed water delivery.

Warm water flushes can also help unclog the tube,12 and additional pharmacologic and mechanical devices have been promoted for clogged tubes. One common technique is mixing pancreatic enzymes (Viokase) with a crushed 325-mg tablet of nonenteric coated sodium bicarbonate and 5 mL of water to create a solution that has the alkaline properties allowing for both pancreatic enzyme activation and clog dissolution. Additionally, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter can be placed into longer feeding tubes to directly infuse the activated agent to the site of the clog.13 If water and enzymes are not successful in unclogging the tube, commercially available brushes can help remove clogs. The TubeClear® system (Actuated Medical, Bellefonte, Penna) has a single-use stem that is connected to AC power to create a jackhammerlike movement to remove clogs in longer nasoenteral and gastrojejunal tubes.

PEG tubes (short-term complications): Procedural and immediate postprocedural complications include bleeding, aspiration, pneumoperitoneum, and perforation. Pneumoperitoneum occurs in approximately 50% of cases and is generally clinically insignificant. The risk of pneumoperitoneum can be reduced by using CO2 insufflation.14 If the patient develops systemic signs of infection or peritoneal signs, CT scan with oral contrast is warranted for further evaluation and to assess for inadvertent perforation of overlying bowel or dislodged tube. Aspiration during or following endoscopy is another common complication of PEG placement and risk factors include over-sedation, supine positioning, advanced age, and neurologic dysfunction. This risk can be mitigated by avoiding over-sedation, immediately aspirating gastric contents when the stomach is reached, and avoiding excessive insufflation.15 In addition, elevating the head of the bed during the procedure and dedicating an assistant to perform oral suctioning during the entire procedure is recommended.

PEG tubes (long-term complications): More delayed complications of PEG insertion include wound infection, buried bumper syndrome, tumor seeding, peristomal leakage, and tube dislodgement. The prevalence of wound infection is 5%- 25%,16 and randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of a single dose of an IV antibiotic (i.e., cephalosporin) in those not already receiving a broad spectrum antibiotic and administered prophylactically before tube placement.17 The significance of this reduction is such that antibiotic administration before tube placement should be considered a quality measure for the procedure. A small amount of redness around the tube site (less than 5 mm) is typical, but extension of erythema, warmth, tenderness, purulent drainage, or systemic symptoms is consistent with infection and warrants additional antibiotic administration. Minor infections can be treated with local antiseptics and oral antibiotics, and early intervention is important to prevent need for hospital admission, systemic antibiotics, and even surgical debridement.

Peristomal leakage is reported in approximately 1%-2% of patients.18 Photographs of the site can be very useful in evaluating and managing peristomal leakage and infections. Interventions include reducing gastric secretions with proton pump inhibitors and management of the skin with barrier creams, such as zinc oxide (Calmoseptine®) ointment. Placement of a larger-diameter tube only enlarges the stoma track and worsens the leakage. In such cases, thorough evaluations for delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis), distal obstruction, or constipation should be performed and managed accordingly. Opiates are common contributors to constipation and delayed gastric emptying and often require reduction in use or directed antagonist therapy to reduce leaking. Continuous feeding over bolus feedings and delivering nutrition distally into the small bowel (PEG-J placement) can improve leaking from gastrostomy tubes. Additional means of management include stabilizing the tube by replacing a traditional tube with a low-profile tube or using right-angle external bumpers. If all measures fail, removing the tube and allowing for stomal closure can be attempted,16 although this option often requires parenteral nutrition support to prevent prolonged periods of inadequate nutrition.

Buried bumper syndrome (BBS) occurs in 1.5%-8.8% of PEG placements and is a common late complication of PEG placement, although early reports have been described.18 The development of BBS occurs when the internal bumper migrates from the gastric lumen through and into the stomach or abdominal wall. It occurs more frequently with solid nonballoon retention tubes and is caused by excessive compression of the external bumper against the skin and abdominal wall. Patients with BBS usually present with an immobile catheter, resistance with feeds (because of a closure of the stomach wall around the internal portion of the gastrostomy tube), abdominal pain, or peristomal leakage. Physicians should be aware of and assess tubes for BBS, in particular when replacing an immobile tube (cannot be pushed into the free stomach lumen) or when there is difficulty in flushing water into the tube. This complication can be easily prevented by allowing a minimum of 0.5-1.0 cm (1 finger breadth) between the external bumper and the abdominal wall. In particular, patients and caregivers should be warned that if the patient gains significant amounts of weight, the outer bumper will need to be loosened. Once BBS is diagnosed, the PEG tube requires removal and replacement as it can cause bleeding, infection, or fasciitis. The general steps to replacement include endoscopic removal of the existing tube and replacement of new PEG in the existing tract as long as the BBS is not severe. In most cases a replacement tube can be pulled into place using the pull-PEG technique at the same gastrostomy site as long as the stoma tract can be cannulated with a wire after the existing tube is removed.

Similar to nasoenteric tubes, PEG tubes can become clogged, although this complication is infrequent. The primary steps for prevention include adequately flushing with water before and after feeds and ensuring that all medications are liquid or well crushed and dissolved before instilling. Timely tube replacement also ensures that the internal portions of the gastrostomy tube remain free of debris. Management is similar to that of unclogging nasoenteral tubes, as discussed above, and specific commercial declogging devices for PEG tubes include the Bionix Declogger® (Bionix Development Corp., Toledo, Ohio) and the Bard® PEG cleaning brush (Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc., Tempe, Ariz.). The Bionix system has a plastic stem with a screw and thread design that will remove clogs in 14-24 French PEG tubes, while the Bard brush has a flexible nylon stem with soft bristles at the end to prevent mucosal injury and can be used for prophylaxis against clogs, as well as removing clogs themselves.12

Lastly, a rare but important complication of PEG placement is tumor seeding of the PEG site in patients with active head and neck or upper gastrointestinal cancer.19 The presumed mechanism is shearing of tumor cells as the PEG is pulled through the upper aerodigestive tract and through the wall of the stomach, as prior studies have demonstrated frequent seeding of tubes and incision sites as shown by brushing the tube for malignant cells after tube placement.20 It is important to recognize this complication and not misdiagnose it as granulation tissue, infection, or bleeding as the spread of the cancer generally portends a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is best to use a PEG insertion technique that does not involve pulling or pushing the PEG through the upper aerodigestive tract in patients with active cancer and instead place tubes via an external approach by colleagues in interventional radiology or via direct surgical placement.

Conclusion

Gastroenterologists occupy a unique role in evaluation, diagnosis, and management of patients requiring enteral feeding. In addition, they are best equipped to place, prevent, and manage complications of tube feeding. For this reason, it is imperative that gastroenterologists familiarize themselves with indications for enteral tubes and types of enteral tubes available, as well as the identification and management of common complications. Comprehensive understanding of these concepts will augment the practicing gastroenterologist’s ability to manage patients requiring enteral nutrition support with confidence.

References

1. Stein DJ et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020 Jun 19. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06396-y.

2. American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee and Clinical Practice and Models of Care Committee. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1590-3.

3. Dietrich CG, Schoppmeyer K. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(20):2464-71.

4. Suzuki Y et al. T Gastroenterology Res.2012 Feb;5(1):10-20.

5. Cheung KS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159(1):81-95.

6. Micic D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep;115(9):1367-70.

7. Fan AC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(6):890-4.

8. Tang SJ. Video J Encycl GI Endosc. 2014;2(2):70-3.

9. Guenter P, Lyman B. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31(6):769-72.

10. Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(1):3-16.

11. Richter JA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):22-34.

12. Boullata JI et al. JPEN. 2017;41(1):15-103.

13. McClave SA. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;3(1):62-8.

14. Murphy CJ et al. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(3):E292. doi: 10.1053/tgie.2001.19915.

15. Lynch CR et al. Pract Gastroenterology. 2004;28:66-77.

16. Hucl T et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30(5):769-81. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.10.002.

17. Jafri NS et al. Aliment Pharmacol & Therapeut. 2007;25(6):647-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03247.x.

18. Blumenstein I et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8505-24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505.

19. Fung E et al. Surgical Endosc. 2017;31(9):3623-7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5394-8.

20. Ellrichmann M et al. Endoscopy. 2013;45(07):526-31. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344023.

Dr. Toy is with the department of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Fang is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Utah.

Introduction

Gastroenterologists are in a unique position to manage individuals with feeding tubes as their training underscores principles in digestion, absorption, nutrition support, and enteral tube placement. Adequate management of individuals with feeding tubes and, importantly, the complications that arise from feeding tube use and placement require a basic understanding of intestinal anatomy and physiology. Therefore, gastroenterologists are well suited to both place and manage individuals with feeding tubes in the long term.

Indications for tube feeding

When deciding on the appropriate route for artificial nutrition support, the first decision to be made is enteral access versus parenteral nutrition support. Enteral nutrition confers multiple benefits, including preservation of the mucosal lining, reductions in complicated infections, decreased costs, and improved patient compliance. All attempts at adequate enteral access should be made before deciding on the use of parenteral nutrition. Following the clinical decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support and enteral access, the next common decision is the anticipated duration of nutrition support. Generally, the oral or nasal tubes are used for short durations (i.e., less than 4 weeks) with percutaneous placement into the stomach or small intestine for longer-term feeding (i.e., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy [PEJ]).

The most general indication for nutrition support is an inability to maintain adequate nutritional needs with oral intake alone. General categories of inadequate oral intake include neurologic disorders, malignancy, and gastrointestinal conditions affecting digestion and absorption (Table 1). Absolute and relative contraindications to PEG placement are listed in Table 2. If an endoscopic placement is not possible, alternative means of placement (i.e., surgery or interventional radiology) can be considered to avoid the consequences of prolonged malnutrition. In-hospital mortality following PEG placement has decreased 40% over the last 10 years, which can be attributed to improved patient selection, enhanced discharge practices, and exclusion of patients with the highest comorbidity and mortality rates, like those with advanced dementia or terminal cancer.1

PEG placement in patients with dementia is controversial, with previous studies not demonstrating improved outcomes and association with high mortality rates,2 so the practice is currently not recommended by the American Geriatrics Society in individuals with advanced dementia.3 However, a large Japanese study showed that careful selection of patients with mild dementia to undergo gastrostomy increased independence fourfold; therefore, multidisciplinary involvement is often necessary in the decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support in this population.4

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed additional strains on endoscopic placement and has highlighted the effect of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) on GI symptoms. A recent meta-analysis showed an overall incidence of GI symptoms of 17.6% in the following conditions in decreasing order of prevalence: anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort.5 In addition, the prolonged ventilatory requirements among a subset of individuals with the most severe COVID-19 results in extended periods of nutrition support via enteral tube placements. In individuals with ICU-acquired weakness and discharge to long-term care facilities, the placement of percutaneous endoscopic tubes may be required, although with the additional consideration of the need for an aerosolizing procedure. Delay of placement has been advocated, in addition to appropriate personal protective equipment, in order to ensure safe placement for the endoscopy staff.6

Types of feeding tubes

After deciding to feed a patient enterally and determining the anticipated duration of enteral support, the next decision is to determine the most appropriate location of feeding delivery: into the stomach or the small bowel. Gastric feeding is advantageous most commonly because of its increased capacity, allowing for larger volumes to be delivered over shorter durations. However, in the setting of postsurgical anatomy, gastroparesis, or obstructing tumors/pancreatic inflammation, distal delivery of tube feeds may be required into the jejunum. Additionally, percutaneous tubes placed into the stomach can have extenders into the small bowel (GJ tubes) to allow for feeding into the small bowel and decompression or delivery of medications into the stomach.

In general, gastric feeding is preferred over small bowel feeding as PEG tubes are more stable and have fewer complications than either PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Gastrostomy tubes are generally shorter and larger in diameter making them less likely to clog. PEG-J tubes have separate lumens for gastric and small intestinal access, but the smaller-bore jejunal extension tubes are more likely to clog or become dislodged. While direct PEJ is shown to have higher rates of tube patency and decreased rates of endoscopic re-intervention, compared with PEG-J,7 one limitation of a direct PEJ is difficulty in placement and site selection, which can be performed with a pediatric colonoscope or balloon enteroscopy system. Most commonly, this procedure is performed under general anesthesia.

In the case of a critically ill patient in the ICU, it is recommended to start enteral nutrition within 24-48 hours of arrival to avoid complications of prolonged calorie deficits. Nasally inserted feeding tubes (e.g., Cortrak, Avanos Medical Devices, Alpharetta, Ga.) are most commonly used at the bedside and can be placed blindly using electromagnetic image guidance, radiographically, or endoscopy. However, the small caliber of nasoenteric tubes comes with the common complication of clogging, which can be overcome with slightly larger bore gastric feeding tubes. If gastric feeding is not tolerated (e.g., in the case of vomiting, witnessed aspiration), small bowel feeding should be initiated and can be a more durable form of enteral feeding with fewer interruptions as feedings do not need to be held for procedures or symptomatic gastric intolerance. In clinical areas of question, or if there is a concern for intolerance of enteral feeding, a short trial with nasogastric or nasojejunal tube placement should be performed before a more definitive percutaneous placement.

With respect to percutaneous tubes, important characteristics to choose are the size (diameter in French units), type of internal retention device, and external appearance of the tube (standard or low profile). All percutaneous tubes contain an external retention device (i.e., bumper) that fits against the skin and an internal retention device that is either a balloon or plastic dome or funnel that prevents the tube from becoming dislodged. Balloon retention tubes require replacement every 3-6 months, while nonballoon tubes generally require replacement annually in order to prevent the plastic from cracking, which can make removal complicated. Low-profile tubes have an external cap, which, when opened, allows for extension tubing to be securely attached while in use and detached while not in use. Low-profile tubes are often preferred among younger, active patients and those with adequate dexterity to allow for attachment of the external extension tubing. These tubes are most often inserted as a replacement for an initially endoscopically placed tube, although one-step systems for initial placement are available. The size of the low-profile tube is chosen based on the size of the existing PEG tube and by measuring the length of the stoma tract using specialized measuring devices.8 Patients and caregivers can also be trained to replace balloon-type tubes on their own to limit complications of displaced or cracked tubes. Low-profile tubes are commercially available for both gastric placement and gastric placement with extension into the small bowel, which often requires fluoroscopy for secure placement.

All percutaneous enteral tubes are being transitioned to the ENfit connector system, which prevents connections from the enteral system to nonenteral systems (namely intravenous lines, chest tubes) and vice versa. Tubing misconnections have been rarely reported, and the EnFIT system is designed to prevent such misadventures that have resulted in serious complications and even mortality.9 Adapter devices are available that may be required for patients with feeding tubes who have not been transitioned yet. Most commonly with new tube placements and replacements, patients and providers will have to become familiar with the new syringes and feeding bags required with EnFIT connectors.

Gastrostomy placement can be considered a higher-risk endoscopic procedure. One complicating factor is the increased use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies in individuals with a history of neurologic insults. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines recommend that coumadin be held 5 days before the procedure and bridged with heparin if the patient is at high risk of thromboembolic complications. For patients on dual anti-platelet therapy, thienopyridines like clopidogrel are often stopped 5-7 days prior to procedure with continuation of aspirin,10 but there are more recent data that PEG insertion is safe with continued use of DAPT.11 Direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) are often stopped 24-48 hours prior to procedure and then restarted 48 hours after tube placement, but this is dependent on the half-life of the specific DOAC and the patient’s renal function. Patients with decreased creatinine clearance may need to hold the DOAC up to 3-4 days prior to the procedure. In this situation, referring to ASGE guidelines and consultation with a hematologist or managing anti-coagulation clinic is advised.10

Troubleshooting complications

Nasoenteric tubes: One of the most common and irritating complications with nasoenteric feeding tubes is clogging. To prevent clogging, the tube should be flushed frequently.12 At least 30 mL of free water should be used to flush the tube every 4-8 hours for continuous feedings or before and after bolus feeding. Additionally, 15-30 mL of water should be given with each separate medication administration, and if possible, medication administration via small-bore small bowel feeding tubes should be avoided.12 Water flushing is especially important with small-caliber tubes and pumps that deliver both feeding and water flushes. It is available for small bowel feeding in order to allow for programmed water delivery.

Warm water flushes can also help unclog the tube,12 and additional pharmacologic and mechanical devices have been promoted for clogged tubes. One common technique is mixing pancreatic enzymes (Viokase) with a crushed 325-mg tablet of nonenteric coated sodium bicarbonate and 5 mL of water to create a solution that has the alkaline properties allowing for both pancreatic enzyme activation and clog dissolution. Additionally, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter can be placed into longer feeding tubes to directly infuse the activated agent to the site of the clog.13 If water and enzymes are not successful in unclogging the tube, commercially available brushes can help remove clogs. The TubeClear® system (Actuated Medical, Bellefonte, Penna) has a single-use stem that is connected to AC power to create a jackhammerlike movement to remove clogs in longer nasoenteral and gastrojejunal tubes.

PEG tubes (short-term complications): Procedural and immediate postprocedural complications include bleeding, aspiration, pneumoperitoneum, and perforation. Pneumoperitoneum occurs in approximately 50% of cases and is generally clinically insignificant. The risk of pneumoperitoneum can be reduced by using CO2 insufflation.14 If the patient develops systemic signs of infection or peritoneal signs, CT scan with oral contrast is warranted for further evaluation and to assess for inadvertent perforation of overlying bowel or dislodged tube. Aspiration during or following endoscopy is another common complication of PEG placement and risk factors include over-sedation, supine positioning, advanced age, and neurologic dysfunction. This risk can be mitigated by avoiding over-sedation, immediately aspirating gastric contents when the stomach is reached, and avoiding excessive insufflation.15 In addition, elevating the head of the bed during the procedure and dedicating an assistant to perform oral suctioning during the entire procedure is recommended.

PEG tubes (long-term complications): More delayed complications of PEG insertion include wound infection, buried bumper syndrome, tumor seeding, peristomal leakage, and tube dislodgement. The prevalence of wound infection is 5%- 25%,16 and randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of a single dose of an IV antibiotic (i.e., cephalosporin) in those not already receiving a broad spectrum antibiotic and administered prophylactically before tube placement.17 The significance of this reduction is such that antibiotic administration before tube placement should be considered a quality measure for the procedure. A small amount of redness around the tube site (less than 5 mm) is typical, but extension of erythema, warmth, tenderness, purulent drainage, or systemic symptoms is consistent with infection and warrants additional antibiotic administration. Minor infections can be treated with local antiseptics and oral antibiotics, and early intervention is important to prevent need for hospital admission, systemic antibiotics, and even surgical debridement.

Peristomal leakage is reported in approximately 1%-2% of patients.18 Photographs of the site can be very useful in evaluating and managing peristomal leakage and infections. Interventions include reducing gastric secretions with proton pump inhibitors and management of the skin with barrier creams, such as zinc oxide (Calmoseptine®) ointment. Placement of a larger-diameter tube only enlarges the stoma track and worsens the leakage. In such cases, thorough evaluations for delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis), distal obstruction, or constipation should be performed and managed accordingly. Opiates are common contributors to constipation and delayed gastric emptying and often require reduction in use or directed antagonist therapy to reduce leaking. Continuous feeding over bolus feedings and delivering nutrition distally into the small bowel (PEG-J placement) can improve leaking from gastrostomy tubes. Additional means of management include stabilizing the tube by replacing a traditional tube with a low-profile tube or using right-angle external bumpers. If all measures fail, removing the tube and allowing for stomal closure can be attempted,16 although this option often requires parenteral nutrition support to prevent prolonged periods of inadequate nutrition.

Buried bumper syndrome (BBS) occurs in 1.5%-8.8% of PEG placements and is a common late complication of PEG placement, although early reports have been described.18 The development of BBS occurs when the internal bumper migrates from the gastric lumen through and into the stomach or abdominal wall. It occurs more frequently with solid nonballoon retention tubes and is caused by excessive compression of the external bumper against the skin and abdominal wall. Patients with BBS usually present with an immobile catheter, resistance with feeds (because of a closure of the stomach wall around the internal portion of the gastrostomy tube), abdominal pain, or peristomal leakage. Physicians should be aware of and assess tubes for BBS, in particular when replacing an immobile tube (cannot be pushed into the free stomach lumen) or when there is difficulty in flushing water into the tube. This complication can be easily prevented by allowing a minimum of 0.5-1.0 cm (1 finger breadth) between the external bumper and the abdominal wall. In particular, patients and caregivers should be warned that if the patient gains significant amounts of weight, the outer bumper will need to be loosened. Once BBS is diagnosed, the PEG tube requires removal and replacement as it can cause bleeding, infection, or fasciitis. The general steps to replacement include endoscopic removal of the existing tube and replacement of new PEG in the existing tract as long as the BBS is not severe. In most cases a replacement tube can be pulled into place using the pull-PEG technique at the same gastrostomy site as long as the stoma tract can be cannulated with a wire after the existing tube is removed.

Similar to nasoenteric tubes, PEG tubes can become clogged, although this complication is infrequent. The primary steps for prevention include adequately flushing with water before and after feeds and ensuring that all medications are liquid or well crushed and dissolved before instilling. Timely tube replacement also ensures that the internal portions of the gastrostomy tube remain free of debris. Management is similar to that of unclogging nasoenteral tubes, as discussed above, and specific commercial declogging devices for PEG tubes include the Bionix Declogger® (Bionix Development Corp., Toledo, Ohio) and the Bard® PEG cleaning brush (Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc., Tempe, Ariz.). The Bionix system has a plastic stem with a screw and thread design that will remove clogs in 14-24 French PEG tubes, while the Bard brush has a flexible nylon stem with soft bristles at the end to prevent mucosal injury and can be used for prophylaxis against clogs, as well as removing clogs themselves.12

Lastly, a rare but important complication of PEG placement is tumor seeding of the PEG site in patients with active head and neck or upper gastrointestinal cancer.19 The presumed mechanism is shearing of tumor cells as the PEG is pulled through the upper aerodigestive tract and through the wall of the stomach, as prior studies have demonstrated frequent seeding of tubes and incision sites as shown by brushing the tube for malignant cells after tube placement.20 It is important to recognize this complication and not misdiagnose it as granulation tissue, infection, or bleeding as the spread of the cancer generally portends a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is best to use a PEG insertion technique that does not involve pulling or pushing the PEG through the upper aerodigestive tract in patients with active cancer and instead place tubes via an external approach by colleagues in interventional radiology or via direct surgical placement.

Conclusion

Gastroenterologists occupy a unique role in evaluation, diagnosis, and management of patients requiring enteral feeding. In addition, they are best equipped to place, prevent, and manage complications of tube feeding. For this reason, it is imperative that gastroenterologists familiarize themselves with indications for enteral tubes and types of enteral tubes available, as well as the identification and management of common complications. Comprehensive understanding of these concepts will augment the practicing gastroenterologist’s ability to manage patients requiring enteral nutrition support with confidence.

References

1. Stein DJ et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020 Jun 19. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06396-y.

2. American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee and Clinical Practice and Models of Care Committee. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1590-3.

3. Dietrich CG, Schoppmeyer K. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(20):2464-71.

4. Suzuki Y et al. T Gastroenterology Res.2012 Feb;5(1):10-20.

5. Cheung KS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159(1):81-95.

6. Micic D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep;115(9):1367-70.

7. Fan AC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(6):890-4.

8. Tang SJ. Video J Encycl GI Endosc. 2014;2(2):70-3.

9. Guenter P, Lyman B. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31(6):769-72.

10. Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(1):3-16.

11. Richter JA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):22-34.

12. Boullata JI et al. JPEN. 2017;41(1):15-103.

13. McClave SA. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;3(1):62-8.

14. Murphy CJ et al. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(3):E292. doi: 10.1053/tgie.2001.19915.

15. Lynch CR et al. Pract Gastroenterology. 2004;28:66-77.

16. Hucl T et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30(5):769-81. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.10.002.

17. Jafri NS et al. Aliment Pharmacol & Therapeut. 2007;25(6):647-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03247.x.

18. Blumenstein I et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8505-24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505.

19. Fung E et al. Surgical Endosc. 2017;31(9):3623-7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5394-8.

20. Ellrichmann M et al. Endoscopy. 2013;45(07):526-31. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344023.

Dr. Toy is with the department of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Fang is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Utah.

Introduction

Gastroenterologists are in a unique position to manage individuals with feeding tubes as their training underscores principles in digestion, absorption, nutrition support, and enteral tube placement. Adequate management of individuals with feeding tubes and, importantly, the complications that arise from feeding tube use and placement require a basic understanding of intestinal anatomy and physiology. Therefore, gastroenterologists are well suited to both place and manage individuals with feeding tubes in the long term.

Indications for tube feeding

When deciding on the appropriate route for artificial nutrition support, the first decision to be made is enteral access versus parenteral nutrition support. Enteral nutrition confers multiple benefits, including preservation of the mucosal lining, reductions in complicated infections, decreased costs, and improved patient compliance. All attempts at adequate enteral access should be made before deciding on the use of parenteral nutrition. Following the clinical decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support and enteral access, the next common decision is the anticipated duration of nutrition support. Generally, the oral or nasal tubes are used for short durations (i.e., less than 4 weeks) with percutaneous placement into the stomach or small intestine for longer-term feeding (i.e., percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy [PEG] or percutaneous endoscopic jejunostomy [PEJ]).

The most general indication for nutrition support is an inability to maintain adequate nutritional needs with oral intake alone. General categories of inadequate oral intake include neurologic disorders, malignancy, and gastrointestinal conditions affecting digestion and absorption (Table 1). Absolute and relative contraindications to PEG placement are listed in Table 2. If an endoscopic placement is not possible, alternative means of placement (i.e., surgery or interventional radiology) can be considered to avoid the consequences of prolonged malnutrition. In-hospital mortality following PEG placement has decreased 40% over the last 10 years, which can be attributed to improved patient selection, enhanced discharge practices, and exclusion of patients with the highest comorbidity and mortality rates, like those with advanced dementia or terminal cancer.1

PEG placement in patients with dementia is controversial, with previous studies not demonstrating improved outcomes and association with high mortality rates,2 so the practice is currently not recommended by the American Geriatrics Society in individuals with advanced dementia.3 However, a large Japanese study showed that careful selection of patients with mild dementia to undergo gastrostomy increased independence fourfold; therefore, multidisciplinary involvement is often necessary in the decision to pursue artificial means of nutrition support in this population.4

The recent coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has placed additional strains on endoscopic placement and has highlighted the effect of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-COV-2) on GI symptoms. A recent meta-analysis showed an overall incidence of GI symptoms of 17.6% in the following conditions in decreasing order of prevalence: anorexia, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal discomfort.5 In addition, the prolonged ventilatory requirements among a subset of individuals with the most severe COVID-19 results in extended periods of nutrition support via enteral tube placements. In individuals with ICU-acquired weakness and discharge to long-term care facilities, the placement of percutaneous endoscopic tubes may be required, although with the additional consideration of the need for an aerosolizing procedure. Delay of placement has been advocated, in addition to appropriate personal protective equipment, in order to ensure safe placement for the endoscopy staff.6

Types of feeding tubes

After deciding to feed a patient enterally and determining the anticipated duration of enteral support, the next decision is to determine the most appropriate location of feeding delivery: into the stomach or the small bowel. Gastric feeding is advantageous most commonly because of its increased capacity, allowing for larger volumes to be delivered over shorter durations. However, in the setting of postsurgical anatomy, gastroparesis, or obstructing tumors/pancreatic inflammation, distal delivery of tube feeds may be required into the jejunum. Additionally, percutaneous tubes placed into the stomach can have extenders into the small bowel (GJ tubes) to allow for feeding into the small bowel and decompression or delivery of medications into the stomach.

In general, gastric feeding is preferred over small bowel feeding as PEG tubes are more stable and have fewer complications than either PEG-J or direct PEJ tubes. Gastrostomy tubes are generally shorter and larger in diameter making them less likely to clog. PEG-J tubes have separate lumens for gastric and small intestinal access, but the smaller-bore jejunal extension tubes are more likely to clog or become dislodged. While direct PEJ is shown to have higher rates of tube patency and decreased rates of endoscopic re-intervention, compared with PEG-J,7 one limitation of a direct PEJ is difficulty in placement and site selection, which can be performed with a pediatric colonoscope or balloon enteroscopy system. Most commonly, this procedure is performed under general anesthesia.

In the case of a critically ill patient in the ICU, it is recommended to start enteral nutrition within 24-48 hours of arrival to avoid complications of prolonged calorie deficits. Nasally inserted feeding tubes (e.g., Cortrak, Avanos Medical Devices, Alpharetta, Ga.) are most commonly used at the bedside and can be placed blindly using electromagnetic image guidance, radiographically, or endoscopy. However, the small caliber of nasoenteric tubes comes with the common complication of clogging, which can be overcome with slightly larger bore gastric feeding tubes. If gastric feeding is not tolerated (e.g., in the case of vomiting, witnessed aspiration), small bowel feeding should be initiated and can be a more durable form of enteral feeding with fewer interruptions as feedings do not need to be held for procedures or symptomatic gastric intolerance. In clinical areas of question, or if there is a concern for intolerance of enteral feeding, a short trial with nasogastric or nasojejunal tube placement should be performed before a more definitive percutaneous placement.

With respect to percutaneous tubes, important characteristics to choose are the size (diameter in French units), type of internal retention device, and external appearance of the tube (standard or low profile). All percutaneous tubes contain an external retention device (i.e., bumper) that fits against the skin and an internal retention device that is either a balloon or plastic dome or funnel that prevents the tube from becoming dislodged. Balloon retention tubes require replacement every 3-6 months, while nonballoon tubes generally require replacement annually in order to prevent the plastic from cracking, which can make removal complicated. Low-profile tubes have an external cap, which, when opened, allows for extension tubing to be securely attached while in use and detached while not in use. Low-profile tubes are often preferred among younger, active patients and those with adequate dexterity to allow for attachment of the external extension tubing. These tubes are most often inserted as a replacement for an initially endoscopically placed tube, although one-step systems for initial placement are available. The size of the low-profile tube is chosen based on the size of the existing PEG tube and by measuring the length of the stoma tract using specialized measuring devices.8 Patients and caregivers can also be trained to replace balloon-type tubes on their own to limit complications of displaced or cracked tubes. Low-profile tubes are commercially available for both gastric placement and gastric placement with extension into the small bowel, which often requires fluoroscopy for secure placement.

All percutaneous enteral tubes are being transitioned to the ENfit connector system, which prevents connections from the enteral system to nonenteral systems (namely intravenous lines, chest tubes) and vice versa. Tubing misconnections have been rarely reported, and the EnFIT system is designed to prevent such misadventures that have resulted in serious complications and even mortality.9 Adapter devices are available that may be required for patients with feeding tubes who have not been transitioned yet. Most commonly with new tube placements and replacements, patients and providers will have to become familiar with the new syringes and feeding bags required with EnFIT connectors.

Gastrostomy placement can be considered a higher-risk endoscopic procedure. One complicating factor is the increased use of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies in individuals with a history of neurologic insults. The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) guidelines recommend that coumadin be held 5 days before the procedure and bridged with heparin if the patient is at high risk of thromboembolic complications. For patients on dual anti-platelet therapy, thienopyridines like clopidogrel are often stopped 5-7 days prior to procedure with continuation of aspirin,10 but there are more recent data that PEG insertion is safe with continued use of DAPT.11 Direct-acting anticoagulants (DOACs) are often stopped 24-48 hours prior to procedure and then restarted 48 hours after tube placement, but this is dependent on the half-life of the specific DOAC and the patient’s renal function. Patients with decreased creatinine clearance may need to hold the DOAC up to 3-4 days prior to the procedure. In this situation, referring to ASGE guidelines and consultation with a hematologist or managing anti-coagulation clinic is advised.10

Troubleshooting complications

Nasoenteric tubes: One of the most common and irritating complications with nasoenteric feeding tubes is clogging. To prevent clogging, the tube should be flushed frequently.12 At least 30 mL of free water should be used to flush the tube every 4-8 hours for continuous feedings or before and after bolus feeding. Additionally, 15-30 mL of water should be given with each separate medication administration, and if possible, medication administration via small-bore small bowel feeding tubes should be avoided.12 Water flushing is especially important with small-caliber tubes and pumps that deliver both feeding and water flushes. It is available for small bowel feeding in order to allow for programmed water delivery.

Warm water flushes can also help unclog the tube,12 and additional pharmacologic and mechanical devices have been promoted for clogged tubes. One common technique is mixing pancreatic enzymes (Viokase) with a crushed 325-mg tablet of nonenteric coated sodium bicarbonate and 5 mL of water to create a solution that has the alkaline properties allowing for both pancreatic enzyme activation and clog dissolution. Additionally, an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) catheter can be placed into longer feeding tubes to directly infuse the activated agent to the site of the clog.13 If water and enzymes are not successful in unclogging the tube, commercially available brushes can help remove clogs. The TubeClear® system (Actuated Medical, Bellefonte, Penna) has a single-use stem that is connected to AC power to create a jackhammerlike movement to remove clogs in longer nasoenteral and gastrojejunal tubes.

PEG tubes (short-term complications): Procedural and immediate postprocedural complications include bleeding, aspiration, pneumoperitoneum, and perforation. Pneumoperitoneum occurs in approximately 50% of cases and is generally clinically insignificant. The risk of pneumoperitoneum can be reduced by using CO2 insufflation.14 If the patient develops systemic signs of infection or peritoneal signs, CT scan with oral contrast is warranted for further evaluation and to assess for inadvertent perforation of overlying bowel or dislodged tube. Aspiration during or following endoscopy is another common complication of PEG placement and risk factors include over-sedation, supine positioning, advanced age, and neurologic dysfunction. This risk can be mitigated by avoiding over-sedation, immediately aspirating gastric contents when the stomach is reached, and avoiding excessive insufflation.15 In addition, elevating the head of the bed during the procedure and dedicating an assistant to perform oral suctioning during the entire procedure is recommended.

PEG tubes (long-term complications): More delayed complications of PEG insertion include wound infection, buried bumper syndrome, tumor seeding, peristomal leakage, and tube dislodgement. The prevalence of wound infection is 5%- 25%,16 and randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of a single dose of an IV antibiotic (i.e., cephalosporin) in those not already receiving a broad spectrum antibiotic and administered prophylactically before tube placement.17 The significance of this reduction is such that antibiotic administration before tube placement should be considered a quality measure for the procedure. A small amount of redness around the tube site (less than 5 mm) is typical, but extension of erythema, warmth, tenderness, purulent drainage, or systemic symptoms is consistent with infection and warrants additional antibiotic administration. Minor infections can be treated with local antiseptics and oral antibiotics, and early intervention is important to prevent need for hospital admission, systemic antibiotics, and even surgical debridement.

Peristomal leakage is reported in approximately 1%-2% of patients.18 Photographs of the site can be very useful in evaluating and managing peristomal leakage and infections. Interventions include reducing gastric secretions with proton pump inhibitors and management of the skin with barrier creams, such as zinc oxide (Calmoseptine®) ointment. Placement of a larger-diameter tube only enlarges the stoma track and worsens the leakage. In such cases, thorough evaluations for delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis), distal obstruction, or constipation should be performed and managed accordingly. Opiates are common contributors to constipation and delayed gastric emptying and often require reduction in use or directed antagonist therapy to reduce leaking. Continuous feeding over bolus feedings and delivering nutrition distally into the small bowel (PEG-J placement) can improve leaking from gastrostomy tubes. Additional means of management include stabilizing the tube by replacing a traditional tube with a low-profile tube or using right-angle external bumpers. If all measures fail, removing the tube and allowing for stomal closure can be attempted,16 although this option often requires parenteral nutrition support to prevent prolonged periods of inadequate nutrition.

Buried bumper syndrome (BBS) occurs in 1.5%-8.8% of PEG placements and is a common late complication of PEG placement, although early reports have been described.18 The development of BBS occurs when the internal bumper migrates from the gastric lumen through and into the stomach or abdominal wall. It occurs more frequently with solid nonballoon retention tubes and is caused by excessive compression of the external bumper against the skin and abdominal wall. Patients with BBS usually present with an immobile catheter, resistance with feeds (because of a closure of the stomach wall around the internal portion of the gastrostomy tube), abdominal pain, or peristomal leakage. Physicians should be aware of and assess tubes for BBS, in particular when replacing an immobile tube (cannot be pushed into the free stomach lumen) or when there is difficulty in flushing water into the tube. This complication can be easily prevented by allowing a minimum of 0.5-1.0 cm (1 finger breadth) between the external bumper and the abdominal wall. In particular, patients and caregivers should be warned that if the patient gains significant amounts of weight, the outer bumper will need to be loosened. Once BBS is diagnosed, the PEG tube requires removal and replacement as it can cause bleeding, infection, or fasciitis. The general steps to replacement include endoscopic removal of the existing tube and replacement of new PEG in the existing tract as long as the BBS is not severe. In most cases a replacement tube can be pulled into place using the pull-PEG technique at the same gastrostomy site as long as the stoma tract can be cannulated with a wire after the existing tube is removed.

Similar to nasoenteric tubes, PEG tubes can become clogged, although this complication is infrequent. The primary steps for prevention include adequately flushing with water before and after feeds and ensuring that all medications are liquid or well crushed and dissolved before instilling. Timely tube replacement also ensures that the internal portions of the gastrostomy tube remain free of debris. Management is similar to that of unclogging nasoenteral tubes, as discussed above, and specific commercial declogging devices for PEG tubes include the Bionix Declogger® (Bionix Development Corp., Toledo, Ohio) and the Bard® PEG cleaning brush (Bard Peripheral Vascular Inc., Tempe, Ariz.). The Bionix system has a plastic stem with a screw and thread design that will remove clogs in 14-24 French PEG tubes, while the Bard brush has a flexible nylon stem with soft bristles at the end to prevent mucosal injury and can be used for prophylaxis against clogs, as well as removing clogs themselves.12

Lastly, a rare but important complication of PEG placement is tumor seeding of the PEG site in patients with active head and neck or upper gastrointestinal cancer.19 The presumed mechanism is shearing of tumor cells as the PEG is pulled through the upper aerodigestive tract and through the wall of the stomach, as prior studies have demonstrated frequent seeding of tubes and incision sites as shown by brushing the tube for malignant cells after tube placement.20 It is important to recognize this complication and not misdiagnose it as granulation tissue, infection, or bleeding as the spread of the cancer generally portends a poor prognosis. Therefore, it is best to use a PEG insertion technique that does not involve pulling or pushing the PEG through the upper aerodigestive tract in patients with active cancer and instead place tubes via an external approach by colleagues in interventional radiology or via direct surgical placement.

Conclusion

Gastroenterologists occupy a unique role in evaluation, diagnosis, and management of patients requiring enteral feeding. In addition, they are best equipped to place, prevent, and manage complications of tube feeding. For this reason, it is imperative that gastroenterologists familiarize themselves with indications for enteral tubes and types of enteral tubes available, as well as the identification and management of common complications. Comprehensive understanding of these concepts will augment the practicing gastroenterologist’s ability to manage patients requiring enteral nutrition support with confidence.

References

1. Stein DJ et al. Dig Dis Sci. 2020 Jun 19. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06396-y.

2. American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee and Clinical Practice and Models of Care Committee. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(8):1590-3.

3. Dietrich CG, Schoppmeyer K. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26(20):2464-71.

4. Suzuki Y et al. T Gastroenterology Res.2012 Feb;5(1):10-20.

5. Cheung KS et al. Gastroenterology. 2020 Jul;159(1):81-95.

6. Micic D et al. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Sep;115(9):1367-70.

7. Fan AC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56(6):890-4.

8. Tang SJ. Video J Encycl GI Endosc. 2014;2(2):70-3.

9. Guenter P, Lyman B. Nutr Clin Pract. 2016;31(6):769-72.

10. Acosta RD et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016;83(1):3-16.

11. Richter JA et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74(1):22-34.

12. Boullata JI et al. JPEN. 2017;41(1):15-103.

13. McClave SA. Tech Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;3(1):62-8.

14. Murphy CJ et al. Endosc Int Open. 2016;4(3):E292. doi: 10.1053/tgie.2001.19915.

15. Lynch CR et al. Pract Gastroenterology. 2004;28:66-77.

16. Hucl T et al. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;30(5):769-81. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2016.10.002.

17. Jafri NS et al. Aliment Pharmacol & Therapeut. 2007;25(6):647-56. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03247.x.

18. Blumenstein I et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(26):8505-24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505.

19. Fung E et al. Surgical Endosc. 2017;31(9):3623-7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-016-5394-8.

20. Ellrichmann M et al. Endoscopy. 2013;45(07):526-31. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1344023.

Dr. Toy is with the department of internal medicine at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City. Dr. Fang is with the division of gastroenterology and hepatology at the University of Utah.