User login

What is the most effective treatment for scabies?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2007 Cochrane review on scabies treatment identified 11 trials that evaluated permethrin for treating scabies.1 In 2 trials, 140 patients were randomized to receive either 200 mcg/kg of oral ivermectin or overnight application of 5% topical permethrin. Topical permethrin was superior to oral ivermectin with failure rates at 2 weeks of 8% and 39%, respectively (number needed to treat [NNT]=4; risk ratio [RR]=4.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.07-10.26).

Two trials compared 5% topical permethrin with 10% topical crotamiton in 194 patients with follow-up at 28 days. Permethrin was superior to crotamiton with failure rates of 6% and 26%, respectively (NNT=6; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.10-0.55).

Five trials with 753 patients compared topical permethrin, 2.5% to 3.5%, with topical 1% lindane, but heterogeneity precluded pooling all the studies. In the 3 studies (554 patients) that were comparable, topical 3.5% permethrin was superior to lindane after a single application of each with failure rates of 9% and 15%, respectively (NNT=17; RR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37-0.95).

Two trials that compared permethrin with topical benzyl benzoate (53 patients) and natural synergized pyrethrins (40 patients) showed no difference in treatment failures, but the trials were small and lacked sufficient statistical power.

Four additional studies included in the review compared crotamiton with lindane (100 patients), lindane with sulfur (68 patients), benzyl benzoate with sulfur (158 patients), and benzyl benzoate with natural synergized pyrethrins (240 patients). None demonstrated superiority, but all were small studies.1 A single small trial of 55 patients that compared oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with placebo showed failure rates at one week of 21% and 85%, respectively (NNT=2; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.12-0.51).1

Topical permethrin vs oral ivermectin

A 2014 systematic review of 5 studies included 2 new studies done after the 2007 Cochrane review.2 The new RCTs compared a single application of 5% topical permethrin with a single dose or 2 doses of oral ivermectin given 2 weeks apart. No statistically significant differences were found in these studies.2 Both underpowered studies favored topical permethrin, however.

The P value was .42 in one study of 242 adults and children, and this trial showed a clinical cure rate at 2 weeks of 93% using topical permethrin vs 86% using oral ivermectin.2

The other study of 120 adults and children didn’t report a P value or identify statistically significant differences between topical permethrin and oral ivermectin.2 This study reported a clinical cure rate of 87% with topical permethrin, 78% with a single dose of oral ivermectin, and 67% with 2 doses of oral ivermectin 2 weeks apart.2

Ivermectin may control endemic scabies better than permethrin

A 2015 randomized controlled trial with 2051 patients compared mass treatments in a scabies-endemic population in Fiji.3 The trial had 3 arms: a standard-care group treated with 5% topical permethrin if symptoms were present and retreated at 2 weeks if symptoms persisted; a permethrin group in which all participants, whether infected or not, received 5% permethrin followed by a second dose at 7 to 14 days if symptoms persisted; and an oral ivermectin group in which participants were treated with 200 mcg/kg, repeated in 7 to 14 days for those with baseline scabies.

At 12 months, the relative risk reductions were 94% (95% CI, 83%-100%) for the ivermectin group, 62% (95% CI, 49%-75%) for the permethrin group, and 49% (95% CI, 37%-60%) for the standard-care group.3 The study had multiple limitations, and all groups were permitted to receive standard care at any time during the 12-month follow-up period. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that endemic scabies control with ivermectin may be superior to topical permethrin.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)4 and the European Guideline for the Management of Scabies5 both recommend topical permethrin as first-line therapy for classical scabies and note that oral ivermectin may be safe and effective but isn’t licensed for scabies treatment in most countries. Ivermectin isn’t approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treating scabies.

The CDC recommendations note that the safety of ivermectin in children weighing less than 15 kg and pregnant women hasn’t been established.4

1. Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD000320.

2. Johnstone P, Strong M. Scabies. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014:1707.

3. Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scabies. Treatment. Available at: www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/health_professionals/meds.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

5. Scott G, Chosidow O. European guideline for the management of scabies, 2010. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:301-303.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2007 Cochrane review on scabies treatment identified 11 trials that evaluated permethrin for treating scabies.1 In 2 trials, 140 patients were randomized to receive either 200 mcg/kg of oral ivermectin or overnight application of 5% topical permethrin. Topical permethrin was superior to oral ivermectin with failure rates at 2 weeks of 8% and 39%, respectively (number needed to treat [NNT]=4; risk ratio [RR]=4.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.07-10.26).

Two trials compared 5% topical permethrin with 10% topical crotamiton in 194 patients with follow-up at 28 days. Permethrin was superior to crotamiton with failure rates of 6% and 26%, respectively (NNT=6; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.10-0.55).

Five trials with 753 patients compared topical permethrin, 2.5% to 3.5%, with topical 1% lindane, but heterogeneity precluded pooling all the studies. In the 3 studies (554 patients) that were comparable, topical 3.5% permethrin was superior to lindane after a single application of each with failure rates of 9% and 15%, respectively (NNT=17; RR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37-0.95).

Two trials that compared permethrin with topical benzyl benzoate (53 patients) and natural synergized pyrethrins (40 patients) showed no difference in treatment failures, but the trials were small and lacked sufficient statistical power.

Four additional studies included in the review compared crotamiton with lindane (100 patients), lindane with sulfur (68 patients), benzyl benzoate with sulfur (158 patients), and benzyl benzoate with natural synergized pyrethrins (240 patients). None demonstrated superiority, but all were small studies.1 A single small trial of 55 patients that compared oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with placebo showed failure rates at one week of 21% and 85%, respectively (NNT=2; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.12-0.51).1

Topical permethrin vs oral ivermectin

A 2014 systematic review of 5 studies included 2 new studies done after the 2007 Cochrane review.2 The new RCTs compared a single application of 5% topical permethrin with a single dose or 2 doses of oral ivermectin given 2 weeks apart. No statistically significant differences were found in these studies.2 Both underpowered studies favored topical permethrin, however.

The P value was .42 in one study of 242 adults and children, and this trial showed a clinical cure rate at 2 weeks of 93% using topical permethrin vs 86% using oral ivermectin.2

The other study of 120 adults and children didn’t report a P value or identify statistically significant differences between topical permethrin and oral ivermectin.2 This study reported a clinical cure rate of 87% with topical permethrin, 78% with a single dose of oral ivermectin, and 67% with 2 doses of oral ivermectin 2 weeks apart.2

Ivermectin may control endemic scabies better than permethrin

A 2015 randomized controlled trial with 2051 patients compared mass treatments in a scabies-endemic population in Fiji.3 The trial had 3 arms: a standard-care group treated with 5% topical permethrin if symptoms were present and retreated at 2 weeks if symptoms persisted; a permethrin group in which all participants, whether infected or not, received 5% permethrin followed by a second dose at 7 to 14 days if symptoms persisted; and an oral ivermectin group in which participants were treated with 200 mcg/kg, repeated in 7 to 14 days for those with baseline scabies.

At 12 months, the relative risk reductions were 94% (95% CI, 83%-100%) for the ivermectin group, 62% (95% CI, 49%-75%) for the permethrin group, and 49% (95% CI, 37%-60%) for the standard-care group.3 The study had multiple limitations, and all groups were permitted to receive standard care at any time during the 12-month follow-up period. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that endemic scabies control with ivermectin may be superior to topical permethrin.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)4 and the European Guideline for the Management of Scabies5 both recommend topical permethrin as first-line therapy for classical scabies and note that oral ivermectin may be safe and effective but isn’t licensed for scabies treatment in most countries. Ivermectin isn’t approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treating scabies.

The CDC recommendations note that the safety of ivermectin in children weighing less than 15 kg and pregnant women hasn’t been established.4

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2007 Cochrane review on scabies treatment identified 11 trials that evaluated permethrin for treating scabies.1 In 2 trials, 140 patients were randomized to receive either 200 mcg/kg of oral ivermectin or overnight application of 5% topical permethrin. Topical permethrin was superior to oral ivermectin with failure rates at 2 weeks of 8% and 39%, respectively (number needed to treat [NNT]=4; risk ratio [RR]=4.61; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.07-10.26).

Two trials compared 5% topical permethrin with 10% topical crotamiton in 194 patients with follow-up at 28 days. Permethrin was superior to crotamiton with failure rates of 6% and 26%, respectively (NNT=6; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.10-0.55).

Five trials with 753 patients compared topical permethrin, 2.5% to 3.5%, with topical 1% lindane, but heterogeneity precluded pooling all the studies. In the 3 studies (554 patients) that were comparable, topical 3.5% permethrin was superior to lindane after a single application of each with failure rates of 9% and 15%, respectively (NNT=17; RR=0.59; 95% CI, 0.37-0.95).

Two trials that compared permethrin with topical benzyl benzoate (53 patients) and natural synergized pyrethrins (40 patients) showed no difference in treatment failures, but the trials were small and lacked sufficient statistical power.

Four additional studies included in the review compared crotamiton with lindane (100 patients), lindane with sulfur (68 patients), benzyl benzoate with sulfur (158 patients), and benzyl benzoate with natural synergized pyrethrins (240 patients). None demonstrated superiority, but all were small studies.1 A single small trial of 55 patients that compared oral ivermectin 200 mcg/kg with placebo showed failure rates at one week of 21% and 85%, respectively (NNT=2; RR=0.24; 95% CI, 0.12-0.51).1

Topical permethrin vs oral ivermectin

A 2014 systematic review of 5 studies included 2 new studies done after the 2007 Cochrane review.2 The new RCTs compared a single application of 5% topical permethrin with a single dose or 2 doses of oral ivermectin given 2 weeks apart. No statistically significant differences were found in these studies.2 Both underpowered studies favored topical permethrin, however.

The P value was .42 in one study of 242 adults and children, and this trial showed a clinical cure rate at 2 weeks of 93% using topical permethrin vs 86% using oral ivermectin.2

The other study of 120 adults and children didn’t report a P value or identify statistically significant differences between topical permethrin and oral ivermectin.2 This study reported a clinical cure rate of 87% with topical permethrin, 78% with a single dose of oral ivermectin, and 67% with 2 doses of oral ivermectin 2 weeks apart.2

Ivermectin may control endemic scabies better than permethrin

A 2015 randomized controlled trial with 2051 patients compared mass treatments in a scabies-endemic population in Fiji.3 The trial had 3 arms: a standard-care group treated with 5% topical permethrin if symptoms were present and retreated at 2 weeks if symptoms persisted; a permethrin group in which all participants, whether infected or not, received 5% permethrin followed by a second dose at 7 to 14 days if symptoms persisted; and an oral ivermectin group in which participants were treated with 200 mcg/kg, repeated in 7 to 14 days for those with baseline scabies.

At 12 months, the relative risk reductions were 94% (95% CI, 83%-100%) for the ivermectin group, 62% (95% CI, 49%-75%) for the permethrin group, and 49% (95% CI, 37%-60%) for the standard-care group.3 The study had multiple limitations, and all groups were permitted to receive standard care at any time during the 12-month follow-up period. Nevertheless, the findings suggest that endemic scabies control with ivermectin may be superior to topical permethrin.

RECOMMENDATIONS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)4 and the European Guideline for the Management of Scabies5 both recommend topical permethrin as first-line therapy for classical scabies and note that oral ivermectin may be safe and effective but isn’t licensed for scabies treatment in most countries. Ivermectin isn’t approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration for treating scabies.

The CDC recommendations note that the safety of ivermectin in children weighing less than 15 kg and pregnant women hasn’t been established.4

1. Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD000320.

2. Johnstone P, Strong M. Scabies. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014:1707.

3. Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scabies. Treatment. Available at: www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/health_professionals/meds.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

5. Scott G, Chosidow O. European guideline for the management of scabies, 2010. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:301-303.

1. Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD000320.

2. Johnstone P, Strong M. Scabies. BMJ Clinical Evidence. 2014:1707.

3. Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, et al. Mass drug administration for scabies control in a population with endemic disease. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2305-2313.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Scabies. Treatment. Available at: www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/health_professionals/meds.html. Accessed February 26, 2016.

5. Scott G, Chosidow O. European guideline for the management of scabies, 2010. Int J STD AIDS. 2011;22:301-303.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Topical permethrin is the most effective treatment for classic scabies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analyses with consistent results).

Topical lindane and crotamiton are inferior to permethrin but appear equivalent to each other and benzyl benzoate, sulfur, and natural synergized pyrethrins (SOR: B, limited randomized trials).

Although not as effective as topical permethrin, oral ivermectin is an effective treatment compared with placebo (SOR: B, a single small randomized trial).

Oral ivermectin may reduce the prevalence of scabies at one year in populations with endemic disease more than topical permethrin (SOR: B, a single randomized trial).

Do ACE inhibitors or ARBs help prevent kidney disease in patients with diabetes and normal BP?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2011 meta-analysis of 5 RCTs (total 2975 patients) that compared ACE inhibitor therapy with placebo in diabetic patients without hypertension and albuminuria found that ACE inhibitors reduced the risk of new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria by 18% (relative risk [RR]=0.82; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.73-0.92).1 Normal albuminuria was defined in all included studies as an albumin excretion rate of <30 mg/d on a timed specimen confirmed with 3 serial measurements.

The RCTs included patients treated with lisinopril, enalapril, and perindopril. All but one examined patients with type 1 diabetes (2781 patients). The study that evaluated type 2 diabetes (194 patients) assessed patients with hypertension who used other antihypertensives to achieve normal blood pressure targets before ACE inhibitor initiation, a potential limitation.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ACE inhibitor therapy reduced the risk of death from any cause (6 studies; 11,350 patients; RR=0.84; 95% CI, 0.73-0.97).1 Patient populations across pooled RCTs were heterogeneous, including subjects with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, with or without hypertension, and with or without albuminuria.

ACE inhibitors increase risk of cough

Patients taking an ACE inhibitor have an increased risk of cough (6 studies; 11,791 patients; RR=1.84; 95% CI, 1.24-2.72).1 ACE inhibitor therapy doesn’t increase the risk of headache or hyperkalemia.

ARBs don’t help prevent diabetic kidney disease in normotensive patients

The 2011 meta-analysis also included 5 RCTs (4604 patients, approximately 3000 with type 2 diabetes and more than 1000 with type 1 diabetes) that compared ARBs with placebo in patients without hypertension.1 Unlike ACE inhibitor therapy, ARB treatment didn’t significantly affect new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria (RR=1.06; 95% CI, 0.67-1.69).

The trials evaluated losartan, candesartan, olmesartan, and valsartan. One study used other antihypertensives to achieve target blood pressure, and another included patients of any albuminuria status.

Compared with placebo or no treatment, ARBs didn’t reduce the risk of death (5 studies; 7653 patients; RR=1.12; 95% CI, 0.88-1.41).1 All 5 RCTs assessed normoalbuminuric patients. Three of the 5 studies examined normotensive patients; one evaluated only hypertensive patients, and another assessed mostly hypertensive patients.

ARBs usually don’t produce significant adverse effects

Within the meta-analysis, ARBs didn’t increase risk of cough, headache, or hyperkalemia.1

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

1. Lv J, Perkovic V, Foote CV, et al. Antihypertensive agents for preventing diabetic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(12):CD004136.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes for angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, no for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs).

In normotensive patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, ACE inhibitor therapy reduces the risk of developing diabetic kidney disease, defined as new-onset microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria, by 18% (strength of recommendation [SOR]: C, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs], disease-oriented evidence).

ACE inhibitor treatment improves all-cause mortality by 16% in patients with diabetes, including patients with and without hypertension. Patients on ACE inhibitor therapy are at increased risk of cough (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

ARB therapy doesn’t lower the risk of developing kidney disease in normotensive patients with type 2 diabetes (SOR: C, meta-analysis of RCTs, disease-oriented evidence); nor does it reduce all-cause mortality in patients with or without hypertension (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs). ARBs aren’t associated with significant adverse events (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs).

Can mobile technology improve weight loss in overweight and obese patients?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

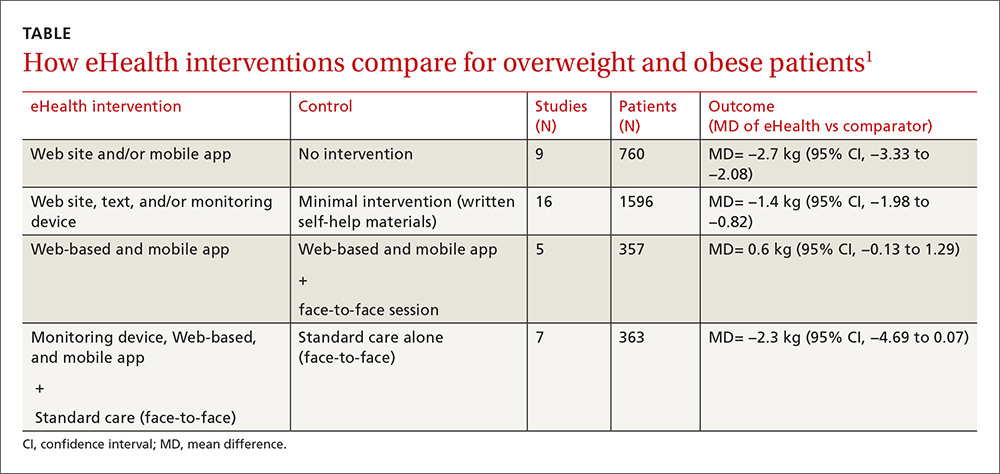

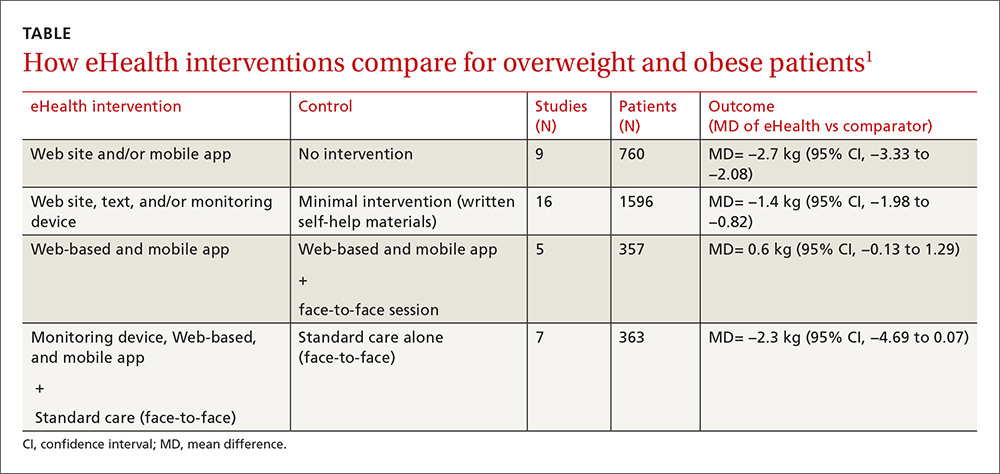

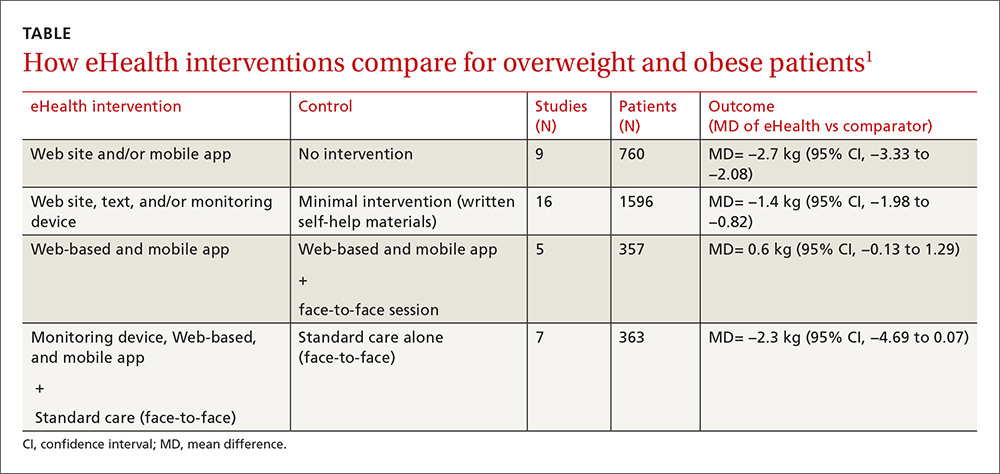

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 84 moderate- to high-quality RCTs with 24,010 patients evaluated the use of “eHealth” interventions in preventing and treating overweight and obesity in adults 35 to 65 years of age (75% female).1 The studies included 183 active intervention arms with durations as long as 24 months (64% <6 months, 46% >6 months). The term eHealth included all forms of information technology used to deliver health care, but predominantly the Internet (Web site/Web-based), e-mail, and text messaging. Sixty percent (84) of eHealth interventional arms used one modality and 34% (47) used 2. Some intervention arms included non-eHealth modalities, such as paper-based measures and counseling.

The eHealth interventions were associated with significantly greater weight loss than minimal or no intervention (TABLE).1 Comparing eHealth interventions with no intervention showed significant differences by eHealth type (P=.05). The greatest weight loss accompanied interventions that combined Web-based measures with a non-eHealth intervention, (mean difference [MD]= −3.7 kg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −4.46 to −2.94), followed by mobile interventions alone (MD= −2.4 kg; 95% CI, −4.09 to −0.71) and Web-based interventions alone (MD= −2.2 kg; 95% CI, −2.98 to −1.44).

Similarly, comparing combined interventions (eHealth + eHealth or eHealth + non-eHealth) with a minimal intervention control showed a trend for difference by eHealth type (P=.005). Only a combination of eHealth with non-eHealth interventions resulted in significantly greater weight loss (Web site + non-eHealth: MD= −2.7 kg; 95% CI, −3.76 to −1.54; text + non-eHealth: MD= −1.8 kg; 95% CI, −2.49 to −1.12; computer + non-eHealth: MD=1.1 kg; 95% CI, −1.36 to −0.89).

Personal coaching plus smartphone monitoring beats interactive app

A 3-arm RCT of 385 overweight and obese participants (mean body mass index [BMI], 35 kg/m2) 18 to 35 years of age compared the effectiveness of weight loss interventions delivered by interactive smartphone application (CP [cell phone]), personal coaching enhanced by smartphone self-monitoring (PC), and usual care (control).2 The PC arm attended 6 weekly group sessions and received monthly phone calls. The usual care arm received 3 handouts on healthy eating and physical activity.

The CP arm showed the least amount of weight loss (−0.9 kg, −1.5 kg, and −1.0 kg at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively) and no significant difference compared with controls at all measurement points. The PC arm had significantly greater weight loss than controls at 6 months (−1.9 kg; 95% CI, −3.17 to −0.67) and significantly greater weight loss than CP at 6 months (−2.2 kg; 95% CI, −3.42 to −0.97) and 12 months (−2.1 kg; 95% CI, −3.94 to −0.27). After 24 months, however, there was no significant difference in mean weight loss among treatment arms.

Automated behavioral program reduced weight and waist circumference

An RCT of 339 prediabetic, overweight, and obese patients 30 to 69 years old (mean BMI, 31 kg/m2) compared the effectiveness of Alive-PD, a fully automated, tailored, behavioral program, to usual care (control) for diabetes prevention.3 In addition to behavioral support, the program included weekly emails, Web-based tracking, a mobile phone app, and automated phone calls.

At 6 months, the intervention group had significantly greater mean weight loss (−3.4 kg vs −1.3 kg; P<.001), mean BMI (−1.1 kg/m2 vs −0.4 kg/m2; P<

Web-based program improves weight loss at 3 months, but not 12 months

An RCT of 65 overweight and obese participants (mean BMI, 32 kg/m2) with at least one cardiovascular risk factor compared the effect of a Web-based program with usual care on weight change at 3, 6, and 12 months.4 Participants in the intervention group were provided with Bluetooth-enabled scales and accelerometer activity bands to allow daily uploads. The Web-based program also provided weekly feedback based on the participant’s performance and a food diary.

The Web-based group had significantly greater weight loss at 3 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.70 to −2.13] vs −0.5 kg [95% CI, −1.55 to 0.52]; P<.001) and 6 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.95 to −1.98] vs −0.8 kg [95% CI, −2.23 to 0.61]; P=.02). At 12 months, however, the groups showed no significant difference (mean= −2.4 kg [95% CI, −3.48 to −0.97] vs −1.8 kg [95% CI, −3.15 to −0.44]; P=.77).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Obesity Society state that electronically delivered weight-loss programs may be prescribed, but may result in smaller weight loss than face-to-face interventions (SOR: B, moderate evidence from RCTs with some limitations or non-randomized trials).5

1. Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Krukowski R, et al. eHealth interventions for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:376-392.

2. Svetkey LP, Batch BC, Lin P, et al. Cell phone intervention for you (CITY): A randomized, controlled trial of behavioral weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:2133-2141.

3. Block G, Azar K, Romanelli R, et al. Diabetes prevention and weight loss with a fully automated behavioral intervention by email, web, and mobile phone: a randomized controlled trial among persons with prediabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e240.

4. Watson S, Woodside J, Ware L, et al. Effect of a web-based behavior change program on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese adults at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e177.

5. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 84 moderate- to high-quality RCTs with 24,010 patients evaluated the use of “eHealth” interventions in preventing and treating overweight and obesity in adults 35 to 65 years of age (75% female).1 The studies included 183 active intervention arms with durations as long as 24 months (64% <6 months, 46% >6 months). The term eHealth included all forms of information technology used to deliver health care, but predominantly the Internet (Web site/Web-based), e-mail, and text messaging. Sixty percent (84) of eHealth interventional arms used one modality and 34% (47) used 2. Some intervention arms included non-eHealth modalities, such as paper-based measures and counseling.

The eHealth interventions were associated with significantly greater weight loss than minimal or no intervention (TABLE).1 Comparing eHealth interventions with no intervention showed significant differences by eHealth type (P=.05). The greatest weight loss accompanied interventions that combined Web-based measures with a non-eHealth intervention, (mean difference [MD]= −3.7 kg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −4.46 to −2.94), followed by mobile interventions alone (MD= −2.4 kg; 95% CI, −4.09 to −0.71) and Web-based interventions alone (MD= −2.2 kg; 95% CI, −2.98 to −1.44).

Similarly, comparing combined interventions (eHealth + eHealth or eHealth + non-eHealth) with a minimal intervention control showed a trend for difference by eHealth type (P=.005). Only a combination of eHealth with non-eHealth interventions resulted in significantly greater weight loss (Web site + non-eHealth: MD= −2.7 kg; 95% CI, −3.76 to −1.54; text + non-eHealth: MD= −1.8 kg; 95% CI, −2.49 to −1.12; computer + non-eHealth: MD=1.1 kg; 95% CI, −1.36 to −0.89).

Personal coaching plus smartphone monitoring beats interactive app

A 3-arm RCT of 385 overweight and obese participants (mean body mass index [BMI], 35 kg/m2) 18 to 35 years of age compared the effectiveness of weight loss interventions delivered by interactive smartphone application (CP [cell phone]), personal coaching enhanced by smartphone self-monitoring (PC), and usual care (control).2 The PC arm attended 6 weekly group sessions and received monthly phone calls. The usual care arm received 3 handouts on healthy eating and physical activity.

The CP arm showed the least amount of weight loss (−0.9 kg, −1.5 kg, and −1.0 kg at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively) and no significant difference compared with controls at all measurement points. The PC arm had significantly greater weight loss than controls at 6 months (−1.9 kg; 95% CI, −3.17 to −0.67) and significantly greater weight loss than CP at 6 months (−2.2 kg; 95% CI, −3.42 to −0.97) and 12 months (−2.1 kg; 95% CI, −3.94 to −0.27). After 24 months, however, there was no significant difference in mean weight loss among treatment arms.

Automated behavioral program reduced weight and waist circumference

An RCT of 339 prediabetic, overweight, and obese patients 30 to 69 years old (mean BMI, 31 kg/m2) compared the effectiveness of Alive-PD, a fully automated, tailored, behavioral program, to usual care (control) for diabetes prevention.3 In addition to behavioral support, the program included weekly emails, Web-based tracking, a mobile phone app, and automated phone calls.

At 6 months, the intervention group had significantly greater mean weight loss (−3.4 kg vs −1.3 kg; P<.001), mean BMI (−1.1 kg/m2 vs −0.4 kg/m2; P<

Web-based program improves weight loss at 3 months, but not 12 months

An RCT of 65 overweight and obese participants (mean BMI, 32 kg/m2) with at least one cardiovascular risk factor compared the effect of a Web-based program with usual care on weight change at 3, 6, and 12 months.4 Participants in the intervention group were provided with Bluetooth-enabled scales and accelerometer activity bands to allow daily uploads. The Web-based program also provided weekly feedback based on the participant’s performance and a food diary.

The Web-based group had significantly greater weight loss at 3 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.70 to −2.13] vs −0.5 kg [95% CI, −1.55 to 0.52]; P<.001) and 6 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.95 to −1.98] vs −0.8 kg [95% CI, −2.23 to 0.61]; P=.02). At 12 months, however, the groups showed no significant difference (mean= −2.4 kg [95% CI, −3.48 to −0.97] vs −1.8 kg [95% CI, −3.15 to −0.44]; P=.77).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Obesity Society state that electronically delivered weight-loss programs may be prescribed, but may result in smaller weight loss than face-to-face interventions (SOR: B, moderate evidence from RCTs with some limitations or non-randomized trials).5

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 84 moderate- to high-quality RCTs with 24,010 patients evaluated the use of “eHealth” interventions in preventing and treating overweight and obesity in adults 35 to 65 years of age (75% female).1 The studies included 183 active intervention arms with durations as long as 24 months (64% <6 months, 46% >6 months). The term eHealth included all forms of information technology used to deliver health care, but predominantly the Internet (Web site/Web-based), e-mail, and text messaging. Sixty percent (84) of eHealth interventional arms used one modality and 34% (47) used 2. Some intervention arms included non-eHealth modalities, such as paper-based measures and counseling.

The eHealth interventions were associated with significantly greater weight loss than minimal or no intervention (TABLE).1 Comparing eHealth interventions with no intervention showed significant differences by eHealth type (P=.05). The greatest weight loss accompanied interventions that combined Web-based measures with a non-eHealth intervention, (mean difference [MD]= −3.7 kg; 95% confidence interval [CI], −4.46 to −2.94), followed by mobile interventions alone (MD= −2.4 kg; 95% CI, −4.09 to −0.71) and Web-based interventions alone (MD= −2.2 kg; 95% CI, −2.98 to −1.44).

Similarly, comparing combined interventions (eHealth + eHealth or eHealth + non-eHealth) with a minimal intervention control showed a trend for difference by eHealth type (P=.005). Only a combination of eHealth with non-eHealth interventions resulted in significantly greater weight loss (Web site + non-eHealth: MD= −2.7 kg; 95% CI, −3.76 to −1.54; text + non-eHealth: MD= −1.8 kg; 95% CI, −2.49 to −1.12; computer + non-eHealth: MD=1.1 kg; 95% CI, −1.36 to −0.89).

Personal coaching plus smartphone monitoring beats interactive app

A 3-arm RCT of 385 overweight and obese participants (mean body mass index [BMI], 35 kg/m2) 18 to 35 years of age compared the effectiveness of weight loss interventions delivered by interactive smartphone application (CP [cell phone]), personal coaching enhanced by smartphone self-monitoring (PC), and usual care (control).2 The PC arm attended 6 weekly group sessions and received monthly phone calls. The usual care arm received 3 handouts on healthy eating and physical activity.

The CP arm showed the least amount of weight loss (−0.9 kg, −1.5 kg, and −1.0 kg at 6, 12, and 24 months, respectively) and no significant difference compared with controls at all measurement points. The PC arm had significantly greater weight loss than controls at 6 months (−1.9 kg; 95% CI, −3.17 to −0.67) and significantly greater weight loss than CP at 6 months (−2.2 kg; 95% CI, −3.42 to −0.97) and 12 months (−2.1 kg; 95% CI, −3.94 to −0.27). After 24 months, however, there was no significant difference in mean weight loss among treatment arms.

Automated behavioral program reduced weight and waist circumference

An RCT of 339 prediabetic, overweight, and obese patients 30 to 69 years old (mean BMI, 31 kg/m2) compared the effectiveness of Alive-PD, a fully automated, tailored, behavioral program, to usual care (control) for diabetes prevention.3 In addition to behavioral support, the program included weekly emails, Web-based tracking, a mobile phone app, and automated phone calls.

At 6 months, the intervention group had significantly greater mean weight loss (−3.4 kg vs −1.3 kg; P<.001), mean BMI (−1.1 kg/m2 vs −0.4 kg/m2; P<

Web-based program improves weight loss at 3 months, but not 12 months

An RCT of 65 overweight and obese participants (mean BMI, 32 kg/m2) with at least one cardiovascular risk factor compared the effect of a Web-based program with usual care on weight change at 3, 6, and 12 months.4 Participants in the intervention group were provided with Bluetooth-enabled scales and accelerometer activity bands to allow daily uploads. The Web-based program also provided weekly feedback based on the participant’s performance and a food diary.

The Web-based group had significantly greater weight loss at 3 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.70 to −2.13] vs −0.5 kg [95% CI, −1.55 to 0.52]; P<.001) and 6 months (mean= −3.4 kg [95% CI, −4.95 to −1.98] vs −0.8 kg [95% CI, −2.23 to 0.61]; P=.02). At 12 months, however, the groups showed no significant difference (mean= −2.4 kg [95% CI, −3.48 to −0.97] vs −1.8 kg [95% CI, −3.15 to −0.44]; P=.77).

RECOMMENDATIONS

Guidelines from the American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association, and Obesity Society state that electronically delivered weight-loss programs may be prescribed, but may result in smaller weight loss than face-to-face interventions (SOR: B, moderate evidence from RCTs with some limitations or non-randomized trials).5

1. Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Krukowski R, et al. eHealth interventions for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:376-392.

2. Svetkey LP, Batch BC, Lin P, et al. Cell phone intervention for you (CITY): A randomized, controlled trial of behavioral weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:2133-2141.

3. Block G, Azar K, Romanelli R, et al. Diabetes prevention and weight loss with a fully automated behavioral intervention by email, web, and mobile phone: a randomized controlled trial among persons with prediabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e240.

4. Watson S, Woodside J, Ware L, et al. Effect of a web-based behavior change program on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese adults at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e177.

5. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

1. Hutchesson MJ, Rollo ME, Krukowski R, et al. eHealth interventions for the prevention and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2015;16:376-392.

2. Svetkey LP, Batch BC, Lin P, et al. Cell phone intervention for you (CITY): A randomized, controlled trial of behavioral weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23:2133-2141.

3. Block G, Azar K, Romanelli R, et al. Diabetes prevention and weight loss with a fully automated behavioral intervention by email, web, and mobile phone: a randomized controlled trial among persons with prediabetes. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e240.

4. Watson S, Woodside J, Ware L, et al. Effect of a web-based behavior change program on weight loss and cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese adults at high risk of developing cardiovascular disease: randomized controlled trial. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e177.

5. Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Circulation. 2014;129:S102-S138.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Yes, this technology can help in the short term. Mobile technology compared with minimal or no intervention increases short-term (<6 months) weight loss (1.4 to 2.7 kg) in overweight and obese patients (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of good-quality studies and randomized controlled trials [RCTs]).

Interventions that combine nonelectronic measures with mobile technology increase weight loss more effectively (3.7 kg) than no intervention (SOR: A, meta-analysis of good-quality studies and RCTs).

Using mobile technology shows no significant benefits for weight loss after 12 months (SOR: A, multiple good-quality RCTs).

Does vitamin D without calcium reduce fracture risk?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

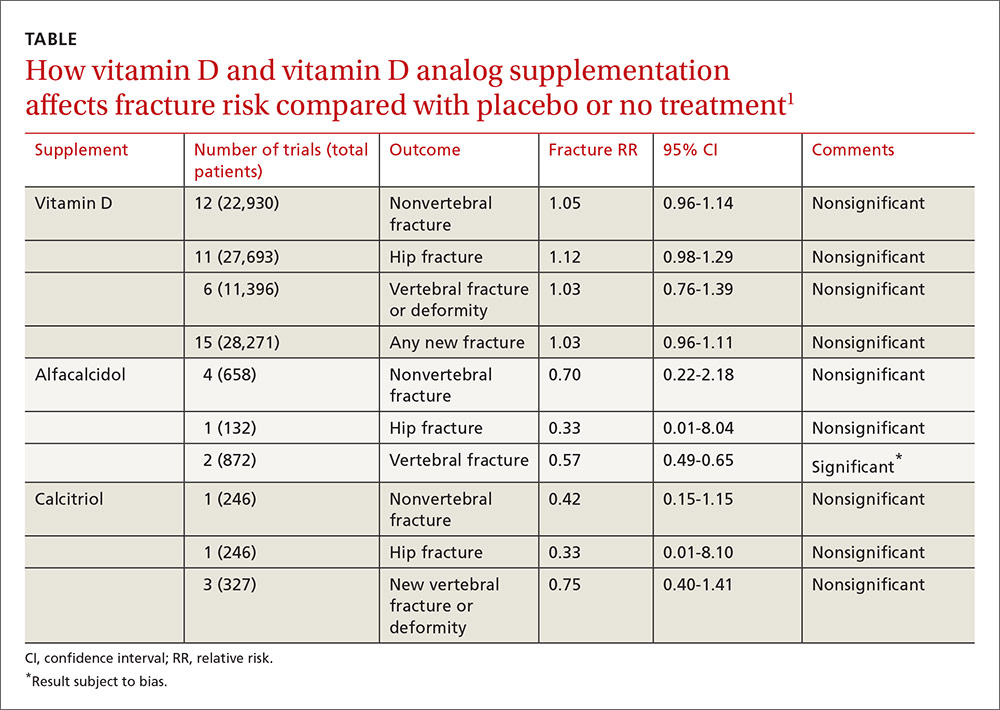

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 meta-analysis of 15 trials (quasi-random and RCT) with a total of 28,271 patients that compared the effect of vitamin D on fracture risk with placebo or no treatment, found no benefit for vitamin D supplementation (TABLE).1 Patients lived in community and nursing home settings and ranged in age from 50 to 85 years; 24% to 100% were female.

Only 3 trials required patients to have had a previous fracture. Exclusions included: diseases affecting bone metabolism, cognitive impairment, drugs affecting bone metabolism (bisphosphonates, selective estrogen receptor modulators, and corticosteroids), renal failure, hypercalcemia, nephrolithiasis, and decreased mobility (recent stroke recovery and Parkinson’s disease).

Formulations of vitamin D included cholecalciferol (D3) 400 to 2000 IU/d for 4 months to 5 years or 100,000 to 500,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 1 to 5 years; calcifediol (25(OH)D3) 600 IU/d for 4 years; and ergocalciferol (D2) 400 IU/d for 2 years or 3000 to 300,000 IU every 3 to 12 months for 10 months to 3 years.

Vitamin D analogs generally have no benefit either

The same meta-analysis compared vitamin D analogs to placebo or no treatment (8 trials, quasi-random and RCT, 1743 patients) on the risk of fracture, again finding no benefit in all but one case. Included patients were mostly by referral to tertiary or university hospitals and outpatient community settings.

Most of the studies included only a small number of patients (about 200), with the largest study having 740 patients. The age range was 50 to 77 years, and 50% to 100% were female. Most of the trials required patients to have osteoporosis or vitamin D deficiency with a previous vertebral deformity on imaging. Study exclusions included osteomalacia, malabsorption, hyperparathyroidism, active kidney stones, history of hypercalciuria, cancer, incurable disease, dementia, severe chronic illness (renal or liver failure), recent stroke or fracture, and drugs that affect bone metabolism.

Vitamin D analogs were given as alfacalcidol (1-alphahydroxyvitamin D3) 0.5 mcg twice daily or 1 mcg/d for 36 weeks to 2 years or calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3) 0.25 to 1 mcg once or twice daily for one to 3 years. Researchers found a significant reduction in vertebral (but not nonvertebral or hip) fractures with alfacalcidol, but the finding occurred in a single trial that was assessed by the authors of the meta-analysis as subject to bias.

Supplementation doesn’t affect mortality, but does have some side effects

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog with or without calcium showed no difference in risk of death compared with patients taking placebo (29 trials, 71,032 patients; relative risk [RR]=0.97; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.93-1.01).

Patients taking vitamin D or an analog were more likely than controls to have mild hypercalcemia, with an average increase of 2.7 mmol/L (21 trials, 17,124 patients; RR=2.28; 95% CI, 1.57-3.31). Patients taking calcitriol had the highest risk (4 trials, 988 patients; RR=4.41; 95% CI, 2.14-9.09).

Gastrointestinal adverse effects (4% increase) and renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency (16% increase) were more common with vitamin D and analogs than placebo (GI adverse effects: 15 trials, 47,761 patients; RR=1.04; 95% CI, 1.00-1.08; renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency: 11 trials, 46,548 patients; RR=1.16; 95% CI, 1.02-1.33).

RECOMMENDATIONS

There are no guidelines recommending vitamin D supplementation without calcium to prevent fracture.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

1. Avenell A, Mak JC, O’Connell D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;4:CD000227.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

No. Supplemental vitamin D without calcium—in doses averaging as much as 800 IU per day—doesn’t reduce the risk of hip, vertebral, or nonvertebral fractures in postmenopausal women and older men (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, large, high-quality meta-analysis of randomized or quasi-randomized placebo-controlled trials).

The vitamin D analogs alfacalcidol and calcitriol also don’t reduce hip or nonvertebral fractures (SOR: A, multiple randomized, controlled trials [RCTs]), although alfacalcidol (but not calcitriol) does reduce vertebral fractures by 43% (SOR: B, one RCT and one quasi-randomized trial with potential for bias)

Vitamin D supplementation, with or without calcium, doesn’t affect mortality. It does double the risk of mild hypercalcemia (about 2.7 mmol/L increase), raise the risk of renal calculi or mild renal insufficiency by 16%, and slightly increase (4%) gastrointestinal adverse effects (SOR: A, meta-analysis of RCTs or quasi-randomized trials).

How do clinical prediction rules compare with joint fluid analysis in diagnosing gout?

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

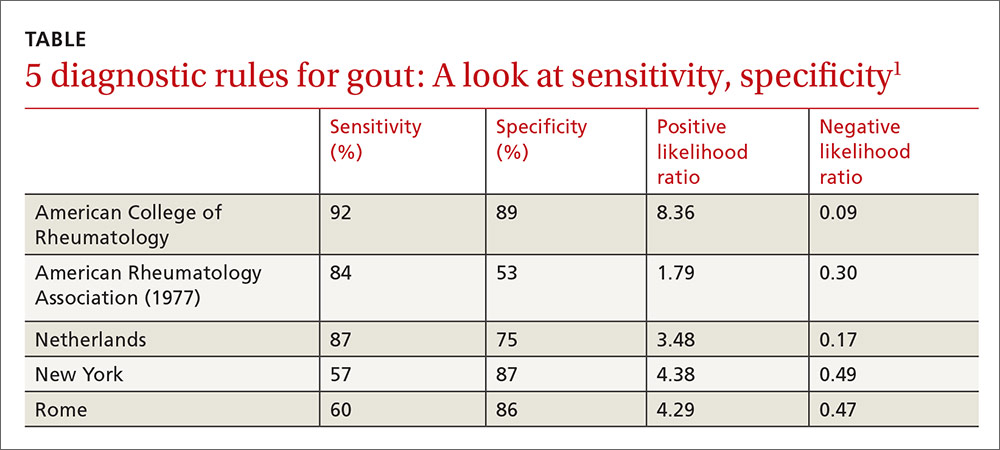

Clinical prediction rules effectively diagnose gout without joint fluid analysis. The American College of Rheumatology clinical prediction rules, the most accurate rules developed for research purposes, have a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 89%, positive likelihood ratio of 8.36, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.09 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, prospective cohort studies).

The Netherlands criteria, developed for use in primary care, have a positive predictive value of more than 80%, a positive likelihood ratio of 3.48, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.17 (SOR: A, prospective cohort study).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In 2015, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) redefined the clinical criteria for diagnosis of gout based on a 3-step system1 that can be found at: http://goutclassificationcalculator.auckland.ac.nz. The ACR rule was derived from a cross-sectional study of 983 patients in 25 rheumatology centers in 16 countries who presented with a swollen joint.2 Of the 983 patients, 509 had gout; the prevalence was 52%. Data from 653 of these patients were used to develop the rule and then validated in the remaining 330 patients.

Compared with the gold standard of monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, the ACR rule has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89%. The rule, designed for the research setting, involves using synovial fluid analysis, ultrasound imaging, and radiography, which makes it less useful in a primary care setting.

The Netherlands rule for primary care

A prospective diagnostic study in 328 family medicine patients (74% male; mean age 57) with monoarthritis tested the ability of multiple clinical variables to diagnose gout using monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid as the gold standard.3 The prevalence of gout in this population was 57%.

The best diagnostic rule (Netherlands rule) comprised the following predefined variables: male sex, previous patient-reported arthritis attack, onset within one day, joint redness, first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP1) involvement, hypertension or cardiovascular disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease), and serum uric acid level above 5.88 mg/dL. The rule gives one point for each item. A score >8 had a positive likelihood ratio for diagnosing gout of 3.48 (TABLE1) and a higher positive predictive value (PPV) than family physicians’ clinical impressions (83% vs 64%).

The prevalence of gout in patients with scores of <4, 4 to 8, and >8 were 2.8%, 27%, and 80%, respectively. For scores of 4 to 8, the probability of gout is indeterminate, and synovial fluid analysis is recommended.

The Netherlands rule, validated in a secondary care practice of 390 patients with monoarthritis, found that a score >8 had a PPV of 87% and a score <4 had a negative predictive value of 95%.4 The probability of gout based on this rule can be calculated at http://www.umcn.nl/goutcalc.

In the study used to develop the Netherlands rule, no patients with a high probability of gout had septic arthritis. The ability of the rule to differentiate between gout and septic arthritis was tested retrospectively in 33 patients with acute gout (podagra excluded) diagnosed by the presence of monosodium urate joint crystals and 27 patients with septic arthritis diagnosed by positive bacterial culture.5 Patients with gout had significantly higher scores than patients with septic arthritis (7.8 ± 1.59 vs 3.4 ± 2.3; P<.001).

American Rheumatology Association, New York, and Rome prediction rules

A study of 82 Veterans Administration patients compared the American Rheumatology Association (ARA), New York, and Rome prediction rules with regard to their ability to diagnose gout with synovial urate crystals.6 The ARA criteria for gout diagnosis require either tophi or monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, or 6 out of a list of 12 other criteria.7

The New York prediction rule requires that patients meet 2 or more of the following criteria: at least 2 attacks of painful joint swelling with complete resolution within 2 weeks, podagra, tophi, and rapid response to colchicine treatment, defined as a major reduction in the objective signs of inflammation within 48 hours.

The Rome prediction rule requires meeting 2 of 3 criteria: serum uric acid >7 mg/dL in men and >6 mg/dL in women, presence of tophi, and history of attacks of painful joint swelling with abrupt onset and resolution within 2 weeks.

The New York prediction rule had the highest positive likelihood ratio of 4.4 compared with the ARA (1.8) and Rome (4.3) rules.6 The utility of the New York and Rome rules, although they have fewer criteria than ARA, is limited by the fact that they include a previous episode of joint swelling and tophi. These criteria increase their specificity but make them less useful in diagnosing a first episode of gout, when tophi are unlikely to have developed.

Prediction rules are more sensitive in established gout

The new ACR prediction rule was compared with the ARA, Rome, and New York clinical prediction rules using urate crystals as the gold standard in early (less than 2 years) and established disease (longer than 2 years).8 All clinical prediction rules were more sensitive in established disease than early disease (95.3% vs 84.1%; P<.001) and more specific in early disease than established disease (79.9% vs 52.5%; P<.001).

1. Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout Classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789-1798.

2. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Jansen TL, et al. Study for Updated Gout Classification Criteria (SUGAR): identification of features to classify gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:1304-1315.

3. Janssens HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1120-1126.

4. Kienhorst LB, Janssens HJ, Fransen J, et al. The validation of a diagnostic rule for gout without joint fluid analysis: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:609-614.

5. Lee K, Choi ST, Kang EJ, et al. SAT0377 The performance of a novel scoring system in the differential diagnosis between acute gout and septic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:A711.

6. Malik A, Schumacher HR, Dinnella JE, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid crystal analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:22.

7. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895-900.

8. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Dalbeth N, et al. Performance of classification criteria for gout in early and established disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:178-182.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Clinical prediction rules effectively diagnose gout without joint fluid analysis. The American College of Rheumatology clinical prediction rules, the most accurate rules developed for research purposes, have a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 89%, positive likelihood ratio of 8.36, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.09 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, prospective cohort studies).

The Netherlands criteria, developed for use in primary care, have a positive predictive value of more than 80%, a positive likelihood ratio of 3.48, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.17 (SOR: A, prospective cohort study).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In 2015, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) redefined the clinical criteria for diagnosis of gout based on a 3-step system1 that can be found at: http://goutclassificationcalculator.auckland.ac.nz. The ACR rule was derived from a cross-sectional study of 983 patients in 25 rheumatology centers in 16 countries who presented with a swollen joint.2 Of the 983 patients, 509 had gout; the prevalence was 52%. Data from 653 of these patients were used to develop the rule and then validated in the remaining 330 patients.

Compared with the gold standard of monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, the ACR rule has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89%. The rule, designed for the research setting, involves using synovial fluid analysis, ultrasound imaging, and radiography, which makes it less useful in a primary care setting.

The Netherlands rule for primary care

A prospective diagnostic study in 328 family medicine patients (74% male; mean age 57) with monoarthritis tested the ability of multiple clinical variables to diagnose gout using monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid as the gold standard.3 The prevalence of gout in this population was 57%.

The best diagnostic rule (Netherlands rule) comprised the following predefined variables: male sex, previous patient-reported arthritis attack, onset within one day, joint redness, first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP1) involvement, hypertension or cardiovascular disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease), and serum uric acid level above 5.88 mg/dL. The rule gives one point for each item. A score >8 had a positive likelihood ratio for diagnosing gout of 3.48 (TABLE1) and a higher positive predictive value (PPV) than family physicians’ clinical impressions (83% vs 64%).

The prevalence of gout in patients with scores of <4, 4 to 8, and >8 were 2.8%, 27%, and 80%, respectively. For scores of 4 to 8, the probability of gout is indeterminate, and synovial fluid analysis is recommended.

The Netherlands rule, validated in a secondary care practice of 390 patients with monoarthritis, found that a score >8 had a PPV of 87% and a score <4 had a negative predictive value of 95%.4 The probability of gout based on this rule can be calculated at http://www.umcn.nl/goutcalc.

In the study used to develop the Netherlands rule, no patients with a high probability of gout had septic arthritis. The ability of the rule to differentiate between gout and septic arthritis was tested retrospectively in 33 patients with acute gout (podagra excluded) diagnosed by the presence of monosodium urate joint crystals and 27 patients with septic arthritis diagnosed by positive bacterial culture.5 Patients with gout had significantly higher scores than patients with septic arthritis (7.8 ± 1.59 vs 3.4 ± 2.3; P<.001).

American Rheumatology Association, New York, and Rome prediction rules

A study of 82 Veterans Administration patients compared the American Rheumatology Association (ARA), New York, and Rome prediction rules with regard to their ability to diagnose gout with synovial urate crystals.6 The ARA criteria for gout diagnosis require either tophi or monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, or 6 out of a list of 12 other criteria.7

The New York prediction rule requires that patients meet 2 or more of the following criteria: at least 2 attacks of painful joint swelling with complete resolution within 2 weeks, podagra, tophi, and rapid response to colchicine treatment, defined as a major reduction in the objective signs of inflammation within 48 hours.

The Rome prediction rule requires meeting 2 of 3 criteria: serum uric acid >7 mg/dL in men and >6 mg/dL in women, presence of tophi, and history of attacks of painful joint swelling with abrupt onset and resolution within 2 weeks.

The New York prediction rule had the highest positive likelihood ratio of 4.4 compared with the ARA (1.8) and Rome (4.3) rules.6 The utility of the New York and Rome rules, although they have fewer criteria than ARA, is limited by the fact that they include a previous episode of joint swelling and tophi. These criteria increase their specificity but make them less useful in diagnosing a first episode of gout, when tophi are unlikely to have developed.

Prediction rules are more sensitive in established gout

The new ACR prediction rule was compared with the ARA, Rome, and New York clinical prediction rules using urate crystals as the gold standard in early (less than 2 years) and established disease (longer than 2 years).8 All clinical prediction rules were more sensitive in established disease than early disease (95.3% vs 84.1%; P<.001) and more specific in early disease than established disease (79.9% vs 52.5%; P<.001).

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

Clinical prediction rules effectively diagnose gout without joint fluid analysis. The American College of Rheumatology clinical prediction rules, the most accurate rules developed for research purposes, have a sensitivity of 92%, specificity of 89%, positive likelihood ratio of 8.36, and negative likelihood ratio of 0.09 (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, prospective cohort studies).

The Netherlands criteria, developed for use in primary care, have a positive predictive value of more than 80%, a positive likelihood ratio of 3.48, and a negative likelihood ratio of 0.17 (SOR: A, prospective cohort study).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In 2015, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) redefined the clinical criteria for diagnosis of gout based on a 3-step system1 that can be found at: http://goutclassificationcalculator.auckland.ac.nz. The ACR rule was derived from a cross-sectional study of 983 patients in 25 rheumatology centers in 16 countries who presented with a swollen joint.2 Of the 983 patients, 509 had gout; the prevalence was 52%. Data from 653 of these patients were used to develop the rule and then validated in the remaining 330 patients.

Compared with the gold standard of monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, the ACR rule has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 89%. The rule, designed for the research setting, involves using synovial fluid analysis, ultrasound imaging, and radiography, which makes it less useful in a primary care setting.

The Netherlands rule for primary care

A prospective diagnostic study in 328 family medicine patients (74% male; mean age 57) with monoarthritis tested the ability of multiple clinical variables to diagnose gout using monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid as the gold standard.3 The prevalence of gout in this population was 57%.

The best diagnostic rule (Netherlands rule) comprised the following predefined variables: male sex, previous patient-reported arthritis attack, onset within one day, joint redness, first metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP1) involvement, hypertension or cardiovascular disease (angina pectoris, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, transient ischemic attack, or peripheral vascular disease), and serum uric acid level above 5.88 mg/dL. The rule gives one point for each item. A score >8 had a positive likelihood ratio for diagnosing gout of 3.48 (TABLE1) and a higher positive predictive value (PPV) than family physicians’ clinical impressions (83% vs 64%).

The prevalence of gout in patients with scores of <4, 4 to 8, and >8 were 2.8%, 27%, and 80%, respectively. For scores of 4 to 8, the probability of gout is indeterminate, and synovial fluid analysis is recommended.

The Netherlands rule, validated in a secondary care practice of 390 patients with monoarthritis, found that a score >8 had a PPV of 87% and a score <4 had a negative predictive value of 95%.4 The probability of gout based on this rule can be calculated at http://www.umcn.nl/goutcalc.

In the study used to develop the Netherlands rule, no patients with a high probability of gout had septic arthritis. The ability of the rule to differentiate between gout and septic arthritis was tested retrospectively in 33 patients with acute gout (podagra excluded) diagnosed by the presence of monosodium urate joint crystals and 27 patients with septic arthritis diagnosed by positive bacterial culture.5 Patients with gout had significantly higher scores than patients with septic arthritis (7.8 ± 1.59 vs 3.4 ± 2.3; P<.001).

American Rheumatology Association, New York, and Rome prediction rules

A study of 82 Veterans Administration patients compared the American Rheumatology Association (ARA), New York, and Rome prediction rules with regard to their ability to diagnose gout with synovial urate crystals.6 The ARA criteria for gout diagnosis require either tophi or monosodium urate crystals in synovial fluid, or 6 out of a list of 12 other criteria.7

The New York prediction rule requires that patients meet 2 or more of the following criteria: at least 2 attacks of painful joint swelling with complete resolution within 2 weeks, podagra, tophi, and rapid response to colchicine treatment, defined as a major reduction in the objective signs of inflammation within 48 hours.

The Rome prediction rule requires meeting 2 of 3 criteria: serum uric acid >7 mg/dL in men and >6 mg/dL in women, presence of tophi, and history of attacks of painful joint swelling with abrupt onset and resolution within 2 weeks.

The New York prediction rule had the highest positive likelihood ratio of 4.4 compared with the ARA (1.8) and Rome (4.3) rules.6 The utility of the New York and Rome rules, although they have fewer criteria than ARA, is limited by the fact that they include a previous episode of joint swelling and tophi. These criteria increase their specificity but make them less useful in diagnosing a first episode of gout, when tophi are unlikely to have developed.

Prediction rules are more sensitive in established gout

The new ACR prediction rule was compared with the ARA, Rome, and New York clinical prediction rules using urate crystals as the gold standard in early (less than 2 years) and established disease (longer than 2 years).8 All clinical prediction rules were more sensitive in established disease than early disease (95.3% vs 84.1%; P<.001) and more specific in early disease than established disease (79.9% vs 52.5%; P<.001).

1. Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout Classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789-1798.

2. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Jansen TL, et al. Study for Updated Gout Classification Criteria (SUGAR): identification of features to classify gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:1304-1315.

3. Janssens HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1120-1126.

4. Kienhorst LB, Janssens HJ, Fransen J, et al. The validation of a diagnostic rule for gout without joint fluid analysis: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:609-614.

5. Lee K, Choi ST, Kang EJ, et al. SAT0377 The performance of a novel scoring system in the differential diagnosis between acute gout and septic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:A711.

6. Malik A, Schumacher HR, Dinnella JE, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid crystal analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:22.

7. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895-900.

8. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Dalbeth N, et al. Performance of classification criteria for gout in early and established disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:178-182.

1. Neogi T, Jansen TL, Dalbeth N, et al. 2015 Gout Classification criteria: an American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1789-1798.

2. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Jansen TL, et al. Study for Updated Gout Classification Criteria (SUGAR): identification of features to classify gout. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015;67:1304-1315.

3. Janssens HJ, Fransen J, van de Lisdonk EH, et al. A diagnostic rule for acute gouty arthritis in primary care without joint fluid analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1120-1126.

4. Kienhorst LB, Janssens HJ, Fransen J, et al. The validation of a diagnostic rule for gout without joint fluid analysis: a prospective study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2015;54:609-614.

5. Lee K, Choi ST, Kang EJ, et al. SAT0377 The performance of a novel scoring system in the differential diagnosis between acute gout and septic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013;72:A711.

6. Malik A, Schumacher HR, Dinnella JE, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria for gout: comparison with the gold standard of synovial fluid crystal analysis. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:22.

7. Wallace SL, Robinson H, Masi AT, et al. Preliminary criteria for the classification of the acute arthritis of primary gout. Arthritis Rheum. 1977;20:895-900.

8. Taylor WJ, Fransen J, Dalbeth N, et al. Performance of classification criteria for gout in early and established disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75:178-182.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Do corticosteroid injections improve carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms?

Yes. Injected corticosteroids reduce symptoms of carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) more effectively than placebo or systemic steroids, but no better than anti-inflammatory medication and splinting, from one to 12 weeks after therapy (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials [RCTs] and consistent RCT).

A 40-mg injection of methylprednisolone reduces symptoms as effectively as an 80-mg injection for as long as 10 weeks, but the 80-mg dose reduces progression to surgery at one year (SOR: B, RCT). Long-term effects of injections decrease by 12 months (SOR: B, RCT).

After corticosteroid injections, 14% of patients proceed to surgery at one year, and 33% proceed to surgery at 5 years (SOR: B, cohort trial).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY