User login

Overcoming LARC complications: 7 case challenges

The use of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods has shown a steady increase in the United States. The major factors for increasing acceptance include high efficacy, ease of use, and an acceptable adverse effect profile. Since these methods require placement under the skin (implantable device) or into the uterus (intrauterine devices [IUDs]), unique management issues arise during their usage. Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a committee opinion addressing several of these clinical challenges—among them: pain with insertion, what to do when the IUD strings are not visualized, and the plan of action for a nonpalpable IUD or contraceptive implant.1 In this article we present 7 cases, and successful management approaches, that reflect ACOG’s recent recommendations and our extensive clinical experience.

Read the first CHALLENGE: Pain with IUD insertion

CHALLENGE 1: Pain with IUD insertion

CASE First-time, nulliparous IUD user apprehensive about insertion pain

A 21-year-old woman (G0) presents for placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD for contraception and treatment of dysmenorrhea. Her medical and surgical histories are unremarkable. She has heard that IUD insertion “is more painful if you haven’t had a baby yet” and she asks what treatments are available to aid in pain relief.

What can you offer her?

A number of approaches have been used to reduce IUD insertion pain, including:

- placing lidocaine gel into or on the cervix

- lidocaine paracervical block

- preinsertion use of misoprostol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Authors of a recent Cochrane review2 indicated that none of these approaches were particularly effective at reducing insertion pain for nulliparous women. Naproxen sodium 550 mg or tramadol 50 mg taken 1 hour prior to IUD insertion have been found to decrease IUD insertion pain in multiparous patients.3 Misoprostol, apart from being ineffective in reducing insertion pain, also requires use for a number of hours before insertion and can cause painful uterine cramping, upset stomach, and diarrhea.2 Some studies do suggest that use of a paracervical block does reduce the pain associated with tenaculum placement but not the IUD insertion itself.

Related article:

Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

A reasonable pain management strategy for nulliparous patients. Given these data, there is not an evidence-based IUD insertion pain management strategy that can be used for the nulliparous case patient. A practical approach for nulliparous patients is to offer naproxen sodium or tramadol, which have been found to be beneficial in multiparous patients, to a nulliparous patient. Additionally, lidocaine gel applied to the cervix or tenaculum-site injection can be considered for tenaculum-associated pain, although it does not appear to help significantly with IUD insertion pain. Misoprostol should be avoided as it does not alleviate the pain of insertion and it can cause bothersome adverse effects.

Read CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CASE No strings palpated 6 weeks after postpartum IUD placement

A 26-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to your office for a postpartum visit 6 weeks after an uncomplicated cesarean delivery at term. She had requested that a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD be placed at the time of delivery, and the delivery report describes an uneventful placement. The patient has not been able to feel the IUD strings using her fingers and you do not find them on examination. She does not remember the IUD falling out.

What are the next steps in her management?

Failure to palpate the IUD strings by the user or failure to visualize the strings is a fairly common occurrence. This is especially true when an IUD is placed immediatelypostpartum, as in this patient’s case.

When the strings cannot be palpated, it is important to exclude pregnancy and recommend a form of backup contraception, such as condoms and emergency contraception if appropriate, until evaluation can be completed.

Steps to locate a device. In the office setting, the strings often can be located by inserting a cytobrush into the endocervical canal to extract them. If that maneuver fails to locate them, an ultrasound should be completed to determine if the device is in the uterus. If the ultrasound does not detect the device in the uterus, obtain an anteroposterior (AP) x-ray encompassing the entire abdomen and pelvis. All IUDs used in the United States are radiopaque and will be observed on x-ray if present. If the IUD is identified, operative removal is indicated.

Related article:

How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound

Intraperitoneal location. If an IUD is found in this location, it is usually the result of a perforation that occurred at the time of insertion. In general, the device can be removed via laparoscopy. Occasionally, laparotomy is needed if there is significant pelvic infection, possible bowel perforation, or if there is an inability to locate the device at laparoscopy.4 The copper IUD is more inflammatory than the levonorgestrel IUDs.

Abdominal location. No matter the IUD type, operative removal of intra-abdominal IUDs should take place expeditiously after they are discovered.

In the case of expulsion. If the IUD is not seen on x-ray, expulsion is the likely cause. Expulsion tends to be more common among5:

- parous users

- those younger than age 20

- placements that immediately follow a delivery or second-trimester abortion.

Nulliparity and type of device are not associated with increased risk of expulsion.

Read CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CASE Strings not palpated in a patient with history of LEEP

A 37-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office for IUD removal. She underwent a loop electrosurgical excision procedure 2 years ago for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 and since then has not been able to feel the IUD strings. On pelvic examination, you do not palpate or visualize the IUD strings after speculum placement.

How can you achieve IUD removal for your patient?

When a patient requests that her IUD be removed, but the strings are not visible and the woman is not pregnant, employ ultrasonography to confirm the IUD remains intrauterine and to rule out expulsion or perforation.

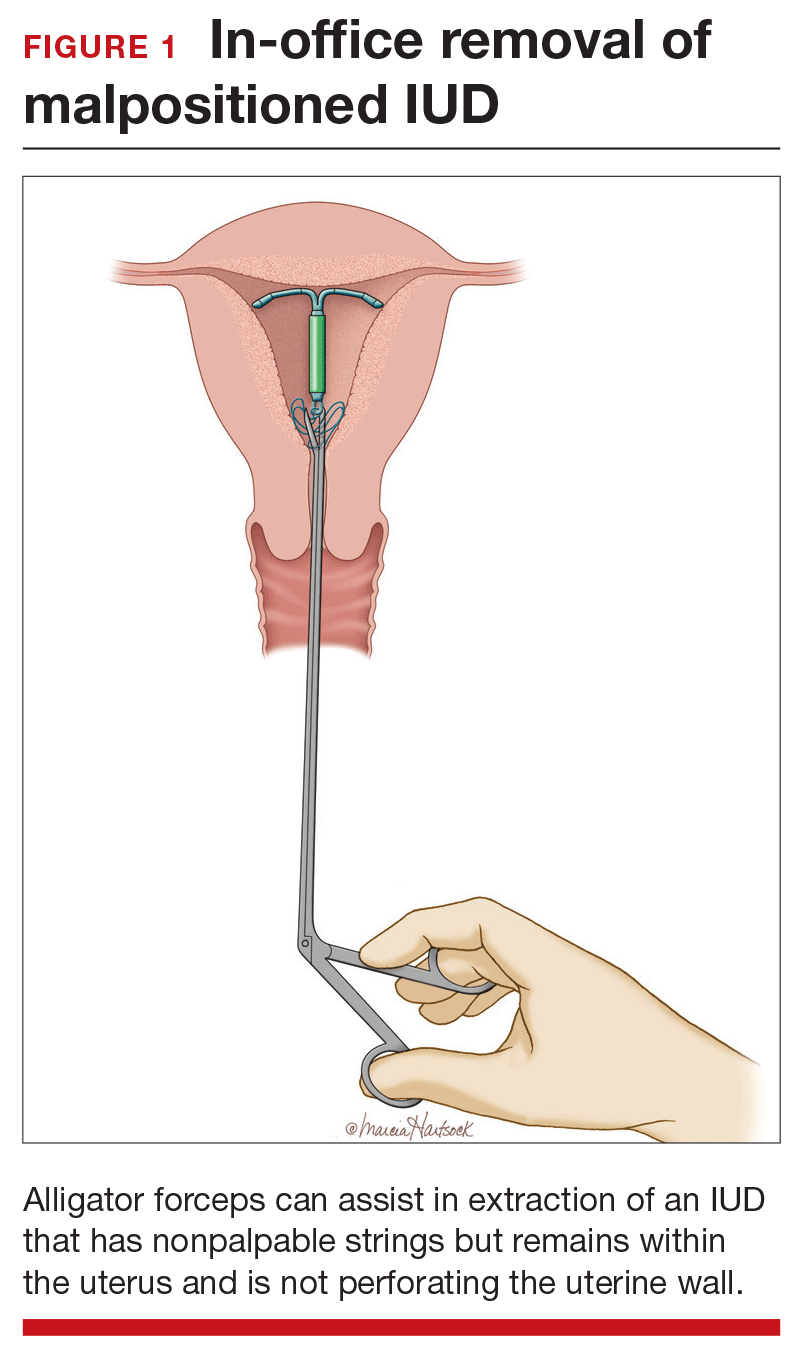

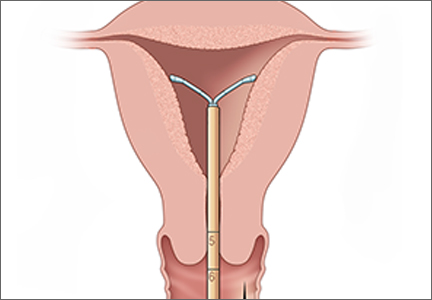

Employ alligator forceps or an IUD hook. Once intrauterine position is confirmed, use an alligator forceps of suitable length and with a small diameter to extract the device (FIGURE 1). It is useful to utilize ultrasonography for guidance during the removal procedure. The alligator forceps will grasp both the IUD device itself and IUD strings well, so either can be targeted during removal.

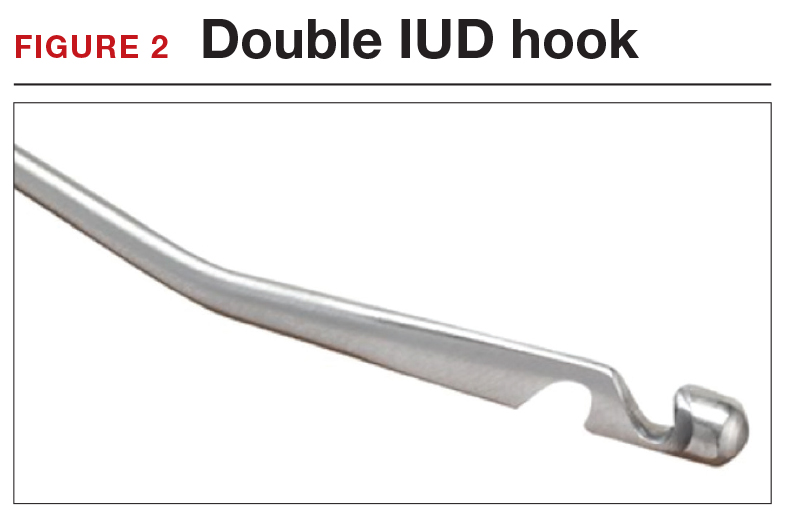

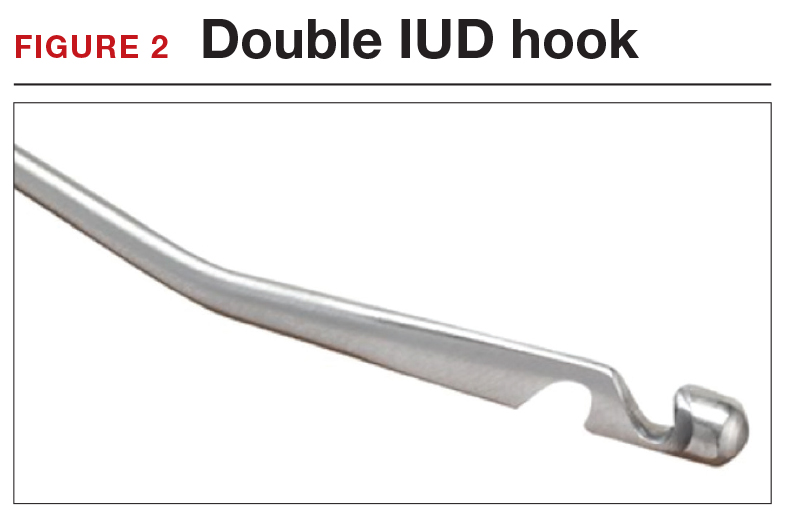

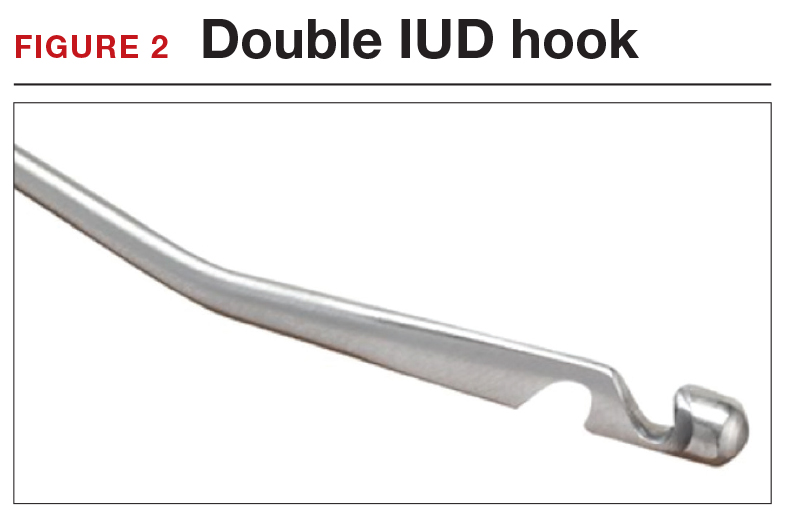

A second useful tool for IUD removal is an IUD hook (FIGURE 2). In a similar way that a curette is used for endometrial sampling, IUD hooks can be used to drag the IUD from the uterus.

Anesthesia is not usually necessary for IUD removal with alligator forceps or an IUD hook, although it may be appropriate in select patients. Data are limited with regard to the utility of paracervical blocks in this situation.

Related article:

Surgical removal of malpositioned IUDs

Hysteroscopy is an option. If removal with an alligator forceps or IUD hook is unsuccessful, or if preferred by the clinician, hysteroscopic-guided removal is a management option. Hysteroscopic removal may be required if the IUD has become embedded in the uterine wall.

Read CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CASE Copper IUD found in lower uterine segment

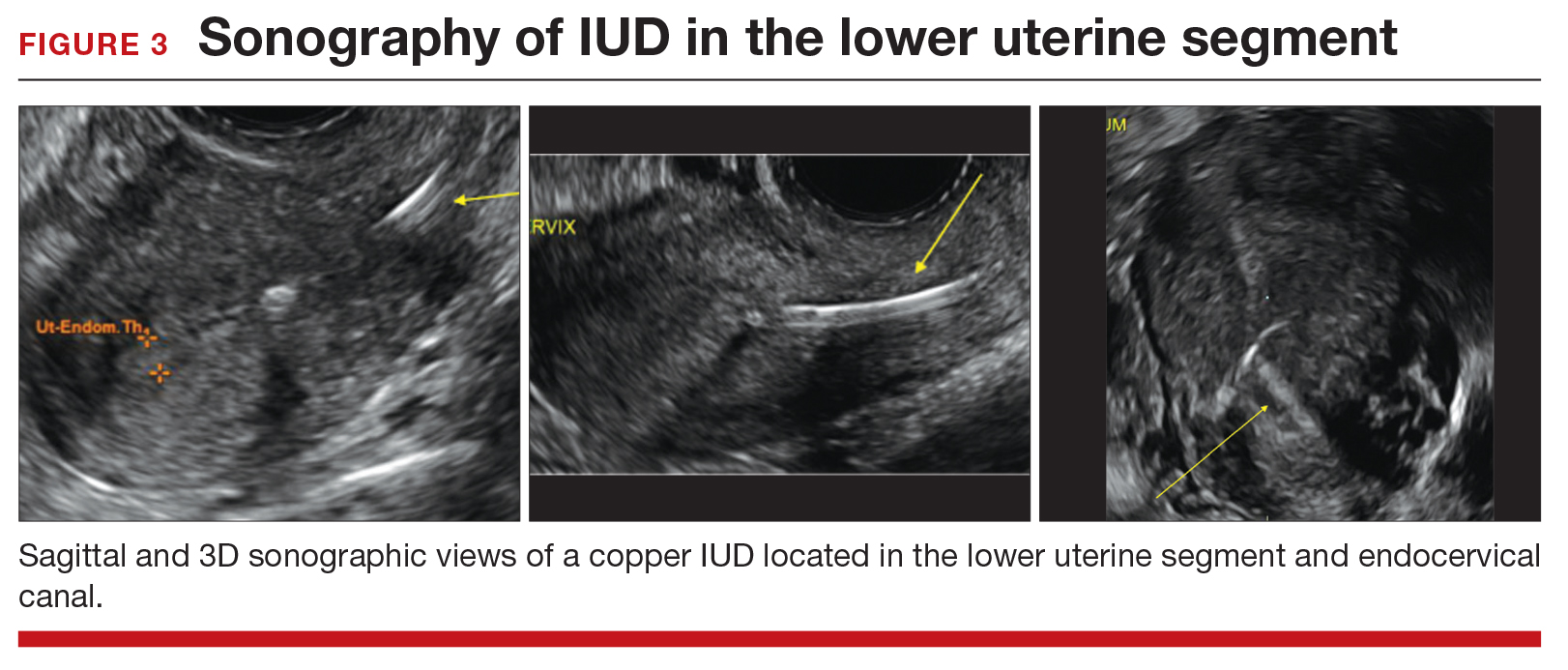

A 31-year-old woman (G1P1) calls your office to report that she thinks her copper IUD strings are longer than before. Office examination confirms that the strings are noticeably longer than is typical. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the copper IUD in the lower uterine segment.

What is the appropriate course of action?

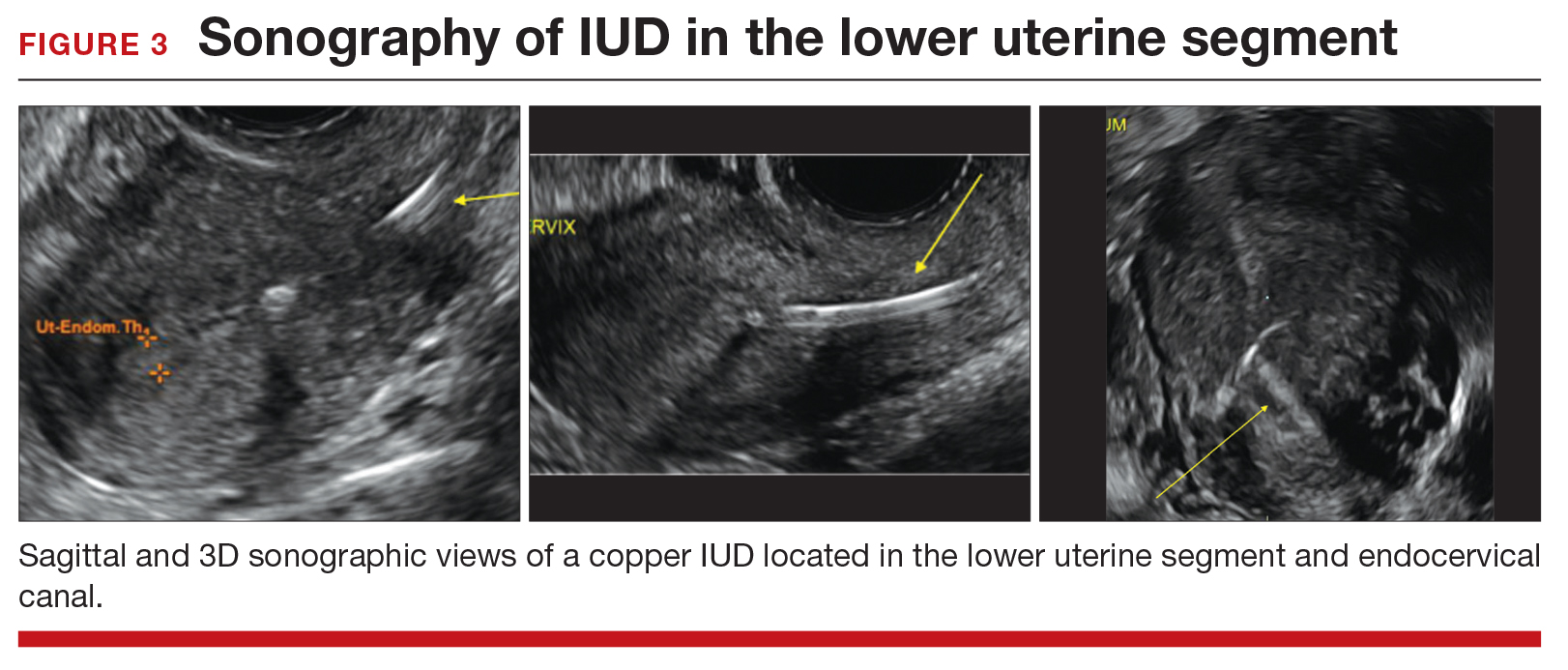

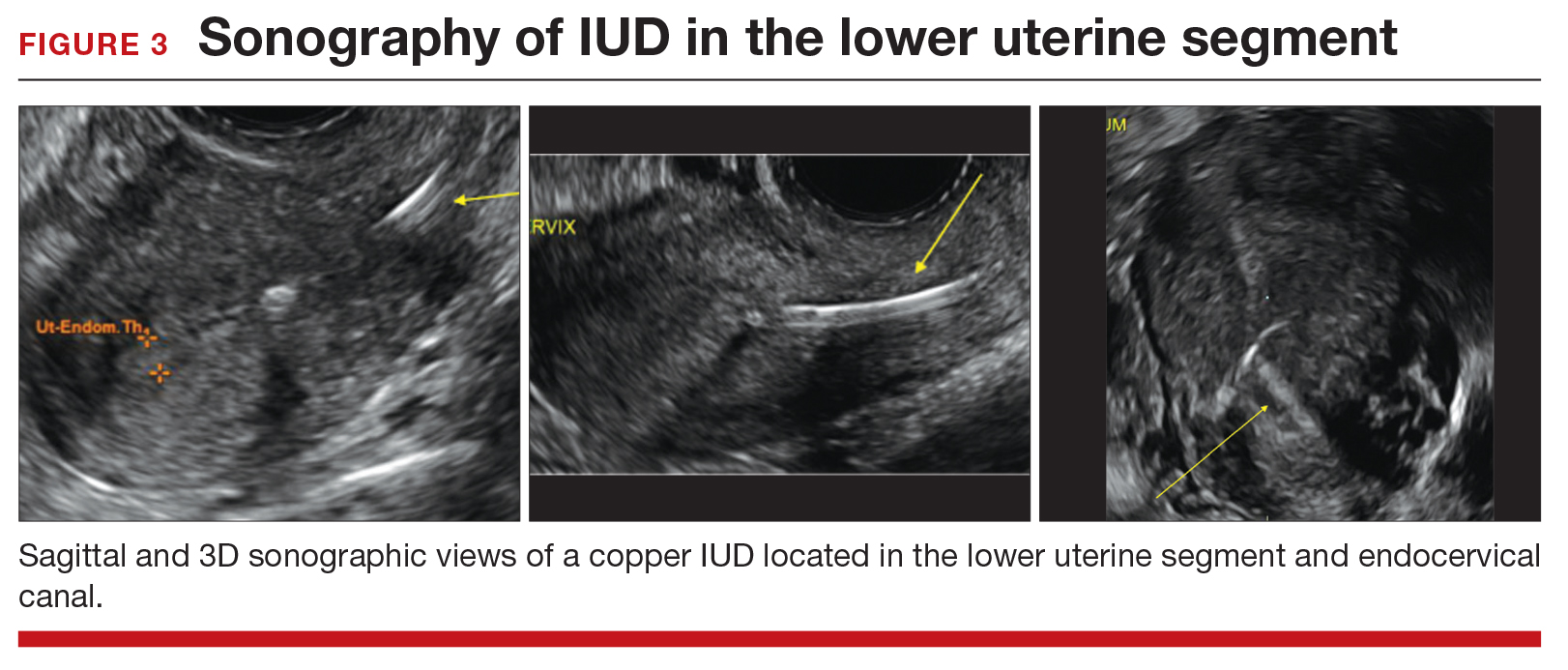

Occasionally, IUDs are noted to be located in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE 3) or cervix. With malposition, users may be experiencing cramping or abnormal bleeding.

Cervical malposition calls for removal. ACOG advises that, regardless of a patient’s presenting symptoms, clinicians should remove IUDs located in the cervix (ie, the stem below the internal os) due to an increased risk of pregnancy and address the woman’s contraceptive needs.

Related article:

STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization

Lower-uterine-segment malposition man‑agement less clear. If the patient is symptomatic, remove the device and initiate some form of contraception. If the woman is asymptomatic, the woman should be given the option of having the device removed or left in place. The mechanisms of action of both the copper and levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs suggest that this lower location is unlikely to be associated with a significant decrease in efficacy.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to estimate the risk of pregnancy for a patient whose device is located in the lower uterine segment. Braaten and Goldberg discussed case-controlled data in their 2012 article that suggest malposition may be more important to the efficacy of copper IUDs than of levonorgestrel IUDs.6,7 As unintended pregnancy is an important risk to avoid, ultimately, it is the woman’s decision as to whether she wants removal or continued IUD use.

Read CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CASE 3-year copper IUD user with positive pregnancy test

A 25-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office because of missed menses and a positive home pregnancy test. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has had a copper IUD in place for 3 years and can feel the strings herself. She has experienced light cramping but no bleeding. Office examination is notable for the IUD stem present at the external cervical os. While the pregnancy is unplanned, the patient desires that it continue.

Should you remove the IUD?

The pregnancy rate among IUD users is less than 1%—a rate that is equivalent to that experienced by women undergoing tubal sterilization. Although there is an overall low risk of pregnancy, a higher proportion of pregnancies among IUD users compared with nonusers are ectopic. Therefore, subsequent management of pregnancy in an IUD user needs to be determined by, using ultrasound, both the location of the pregnancy and whether the IUD is in place.

If an ectopic pregnancy is found, it may be managed medically or surgically with the IUD left in place if desired. If you find an intrauterine pregnancy that is undesired, the IUD can be removed at the time of a surgical abortion or before the initiation of a medical abortion.

If you fail to locate the IUD either before or after the abortion procedure, use an AP x-ray of the entire abdomen and pelvis to determine whether the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity or whether it was likely expelled prior to the pregnancy.

Related article:

In which clinical situations can the use of the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena) and the TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) be extended?

With a desired pregnancy, if the strings are visible, remove the IUD with gentle traction. If the IUD is left in place, the risk of spontaneous abortion is significantly increased. If the strings are not seen, but the device was noted to be in the cervix by ultrasound, remove the device if the stem is below the internal cervical os. For IUDs that are located above the cervix, removal should not be attempted; counsel the patient about the increased risk of spontaneous abortion, infection, and preterm delivery.

Read CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CASE 3-week implant user with positive pregnancy test

Your 21-year-old patient who received a contraceptive implant 3 weeks earlier now pre‑sents with nausea and abdominal cramping. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has regular cycles that are 28 days in length. Results of urine pregnancy testing are positive. Prior to using the implant, the patient inconsistently used condoms.

How should you counsel your patient?

The rate of pregnancy among implant users is very low; it is estimated at 5 pregnancies per 10,000 implant users per year.8 As in this case, apparent “failures” of the contraceptive implant actually may represent placements that occurred before a very early pregnancy was recognized. Similar to IUDs, the proportion of pregnancies that are ectopic among implant users compared to nonusers may be higher.

With a pregnancy that is ectopic or that is intrauterine and undesired, the device may be left in and use continued after the pregnancy has been terminated. Although the effectiveness of medication abortion with pre-existing contraceptive implant in situ is not well known, researchers have demonstrated that medication abortion initiated at the same time as contraceptive implant insertion does not influence success of the medication abortion.9

Related article:

2016 Update on contraception

For women with desired intrauterine pregnancies, remove the device as soon as feasible and counsel the woman that there is no known teratogenic risk associated with the contraceptive implant.

Read CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CASE Patient requests device removal to attempt conception

A 30-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for contraceptive implant removal because she would like to have another child. The device was placed 30 months ago in the patient’s left arm. The insertion note in the patient’s medical record is unremarkable, and standard insertion technique was used. On physical examination, you cannot palpate the device.

What is your next course of action?

Nonpalpable implants, particularly if removal is desired, present a significant clinical challenge. Do not attempt removing a nonpalpable implant before trying to locate the device through past medical records or radiography. Records that describe the original insertion, particularly the location and type of device, are helpful.

Related article:

2015 Update on contraception

Appropriate imaging assistance. Ultrasonography with a high frequency linear array transducer (10 MHz or greater) may allow an experienced radiologist to identify the implant—including earlier versions without barium (Implanon) and later ones with barium (Nexplanon). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography scan, or plain x-ray also can be used to detect a barium-containing device; MRI can be used to locate a non−barium-containing implant.

Carry out removal using ultrasonographic guidance. If a deep insertion is felt to be close to a neurovascular bundle, device removal should be carried out in an operating room by a surgeon familiar with the anatomy of the upper arm.

When an implant cannot be located despite radiography. This is an infrequent occurrence. Merck, the manufacturer of the etonorgestrel implant, provides advice and support in this circumstance. (Visit https://www.merckconnect.com/nexplanon/over view.html.)

Recently, published case reports detail episodes of implants inserted into the venous system with migration to the heart or lungs.10 While this phenomenon is considered rare, the manufacturer has recommended that insertion of the contraceptive implant avoid the sulcus between the biceps and triceps muscles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e69−e77.

- Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Zeng Y, et al. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD007373.

- Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581−584.

- Kho KA, Chamsy DJ. Perforated intraperitoneal intrauterine contraceptive devices: diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):596−601.

- Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Eisenberg DL, Peipert JF. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):718−726.

- Patil E, Bednarek PH. Immediate intrauterine device insertion following surgical abortion. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(4):583−546.

- Braaten and Goldberg. OBG Manag. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):38−46.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397−404.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan YL, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;127(2):306−312.

- Rowlands S, Mansour D, Walling M. Intravascular migration of contraceptive implants: two more cases. Contraception. 2016. In press.

The use of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods has shown a steady increase in the United States. The major factors for increasing acceptance include high efficacy, ease of use, and an acceptable adverse effect profile. Since these methods require placement under the skin (implantable device) or into the uterus (intrauterine devices [IUDs]), unique management issues arise during their usage. Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a committee opinion addressing several of these clinical challenges—among them: pain with insertion, what to do when the IUD strings are not visualized, and the plan of action for a nonpalpable IUD or contraceptive implant.1 In this article we present 7 cases, and successful management approaches, that reflect ACOG’s recent recommendations and our extensive clinical experience.

Read the first CHALLENGE: Pain with IUD insertion

CHALLENGE 1: Pain with IUD insertion

CASE First-time, nulliparous IUD user apprehensive about insertion pain

A 21-year-old woman (G0) presents for placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD for contraception and treatment of dysmenorrhea. Her medical and surgical histories are unremarkable. She has heard that IUD insertion “is more painful if you haven’t had a baby yet” and she asks what treatments are available to aid in pain relief.

What can you offer her?

A number of approaches have been used to reduce IUD insertion pain, including:

- placing lidocaine gel into or on the cervix

- lidocaine paracervical block

- preinsertion use of misoprostol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Authors of a recent Cochrane review2 indicated that none of these approaches were particularly effective at reducing insertion pain for nulliparous women. Naproxen sodium 550 mg or tramadol 50 mg taken 1 hour prior to IUD insertion have been found to decrease IUD insertion pain in multiparous patients.3 Misoprostol, apart from being ineffective in reducing insertion pain, also requires use for a number of hours before insertion and can cause painful uterine cramping, upset stomach, and diarrhea.2 Some studies do suggest that use of a paracervical block does reduce the pain associated with tenaculum placement but not the IUD insertion itself.

Related article:

Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

A reasonable pain management strategy for nulliparous patients. Given these data, there is not an evidence-based IUD insertion pain management strategy that can be used for the nulliparous case patient. A practical approach for nulliparous patients is to offer naproxen sodium or tramadol, which have been found to be beneficial in multiparous patients, to a nulliparous patient. Additionally, lidocaine gel applied to the cervix or tenaculum-site injection can be considered for tenaculum-associated pain, although it does not appear to help significantly with IUD insertion pain. Misoprostol should be avoided as it does not alleviate the pain of insertion and it can cause bothersome adverse effects.

Read CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CASE No strings palpated 6 weeks after postpartum IUD placement

A 26-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to your office for a postpartum visit 6 weeks after an uncomplicated cesarean delivery at term. She had requested that a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD be placed at the time of delivery, and the delivery report describes an uneventful placement. The patient has not been able to feel the IUD strings using her fingers and you do not find them on examination. She does not remember the IUD falling out.

What are the next steps in her management?

Failure to palpate the IUD strings by the user or failure to visualize the strings is a fairly common occurrence. This is especially true when an IUD is placed immediatelypostpartum, as in this patient’s case.

When the strings cannot be palpated, it is important to exclude pregnancy and recommend a form of backup contraception, such as condoms and emergency contraception if appropriate, until evaluation can be completed.

Steps to locate a device. In the office setting, the strings often can be located by inserting a cytobrush into the endocervical canal to extract them. If that maneuver fails to locate them, an ultrasound should be completed to determine if the device is in the uterus. If the ultrasound does not detect the device in the uterus, obtain an anteroposterior (AP) x-ray encompassing the entire abdomen and pelvis. All IUDs used in the United States are radiopaque and will be observed on x-ray if present. If the IUD is identified, operative removal is indicated.

Related article:

How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound

Intraperitoneal location. If an IUD is found in this location, it is usually the result of a perforation that occurred at the time of insertion. In general, the device can be removed via laparoscopy. Occasionally, laparotomy is needed if there is significant pelvic infection, possible bowel perforation, or if there is an inability to locate the device at laparoscopy.4 The copper IUD is more inflammatory than the levonorgestrel IUDs.

Abdominal location. No matter the IUD type, operative removal of intra-abdominal IUDs should take place expeditiously after they are discovered.

In the case of expulsion. If the IUD is not seen on x-ray, expulsion is the likely cause. Expulsion tends to be more common among5:

- parous users

- those younger than age 20

- placements that immediately follow a delivery or second-trimester abortion.

Nulliparity and type of device are not associated with increased risk of expulsion.

Read CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CASE Strings not palpated in a patient with history of LEEP

A 37-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office for IUD removal. She underwent a loop electrosurgical excision procedure 2 years ago for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 and since then has not been able to feel the IUD strings. On pelvic examination, you do not palpate or visualize the IUD strings after speculum placement.

How can you achieve IUD removal for your patient?

When a patient requests that her IUD be removed, but the strings are not visible and the woman is not pregnant, employ ultrasonography to confirm the IUD remains intrauterine and to rule out expulsion or perforation.

Employ alligator forceps or an IUD hook. Once intrauterine position is confirmed, use an alligator forceps of suitable length and with a small diameter to extract the device (FIGURE 1). It is useful to utilize ultrasonography for guidance during the removal procedure. The alligator forceps will grasp both the IUD device itself and IUD strings well, so either can be targeted during removal.

A second useful tool for IUD removal is an IUD hook (FIGURE 2). In a similar way that a curette is used for endometrial sampling, IUD hooks can be used to drag the IUD from the uterus.

Anesthesia is not usually necessary for IUD removal with alligator forceps or an IUD hook, although it may be appropriate in select patients. Data are limited with regard to the utility of paracervical blocks in this situation.

Related article:

Surgical removal of malpositioned IUDs

Hysteroscopy is an option. If removal with an alligator forceps or IUD hook is unsuccessful, or if preferred by the clinician, hysteroscopic-guided removal is a management option. Hysteroscopic removal may be required if the IUD has become embedded in the uterine wall.

Read CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CASE Copper IUD found in lower uterine segment

A 31-year-old woman (G1P1) calls your office to report that she thinks her copper IUD strings are longer than before. Office examination confirms that the strings are noticeably longer than is typical. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the copper IUD in the lower uterine segment.

What is the appropriate course of action?

Occasionally, IUDs are noted to be located in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE 3) or cervix. With malposition, users may be experiencing cramping or abnormal bleeding.

Cervical malposition calls for removal. ACOG advises that, regardless of a patient’s presenting symptoms, clinicians should remove IUDs located in the cervix (ie, the stem below the internal os) due to an increased risk of pregnancy and address the woman’s contraceptive needs.

Related article:

STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization

Lower-uterine-segment malposition man‑agement less clear. If the patient is symptomatic, remove the device and initiate some form of contraception. If the woman is asymptomatic, the woman should be given the option of having the device removed or left in place. The mechanisms of action of both the copper and levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs suggest that this lower location is unlikely to be associated with a significant decrease in efficacy.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to estimate the risk of pregnancy for a patient whose device is located in the lower uterine segment. Braaten and Goldberg discussed case-controlled data in their 2012 article that suggest malposition may be more important to the efficacy of copper IUDs than of levonorgestrel IUDs.6,7 As unintended pregnancy is an important risk to avoid, ultimately, it is the woman’s decision as to whether she wants removal or continued IUD use.

Read CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CASE 3-year copper IUD user with positive pregnancy test

A 25-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office because of missed menses and a positive home pregnancy test. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has had a copper IUD in place for 3 years and can feel the strings herself. She has experienced light cramping but no bleeding. Office examination is notable for the IUD stem present at the external cervical os. While the pregnancy is unplanned, the patient desires that it continue.

Should you remove the IUD?

The pregnancy rate among IUD users is less than 1%—a rate that is equivalent to that experienced by women undergoing tubal sterilization. Although there is an overall low risk of pregnancy, a higher proportion of pregnancies among IUD users compared with nonusers are ectopic. Therefore, subsequent management of pregnancy in an IUD user needs to be determined by, using ultrasound, both the location of the pregnancy and whether the IUD is in place.

If an ectopic pregnancy is found, it may be managed medically or surgically with the IUD left in place if desired. If you find an intrauterine pregnancy that is undesired, the IUD can be removed at the time of a surgical abortion or before the initiation of a medical abortion.

If you fail to locate the IUD either before or after the abortion procedure, use an AP x-ray of the entire abdomen and pelvis to determine whether the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity or whether it was likely expelled prior to the pregnancy.

Related article:

In which clinical situations can the use of the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena) and the TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) be extended?

With a desired pregnancy, if the strings are visible, remove the IUD with gentle traction. If the IUD is left in place, the risk of spontaneous abortion is significantly increased. If the strings are not seen, but the device was noted to be in the cervix by ultrasound, remove the device if the stem is below the internal cervical os. For IUDs that are located above the cervix, removal should not be attempted; counsel the patient about the increased risk of spontaneous abortion, infection, and preterm delivery.

Read CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CASE 3-week implant user with positive pregnancy test

Your 21-year-old patient who received a contraceptive implant 3 weeks earlier now pre‑sents with nausea and abdominal cramping. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has regular cycles that are 28 days in length. Results of urine pregnancy testing are positive. Prior to using the implant, the patient inconsistently used condoms.

How should you counsel your patient?

The rate of pregnancy among implant users is very low; it is estimated at 5 pregnancies per 10,000 implant users per year.8 As in this case, apparent “failures” of the contraceptive implant actually may represent placements that occurred before a very early pregnancy was recognized. Similar to IUDs, the proportion of pregnancies that are ectopic among implant users compared to nonusers may be higher.

With a pregnancy that is ectopic or that is intrauterine and undesired, the device may be left in and use continued after the pregnancy has been terminated. Although the effectiveness of medication abortion with pre-existing contraceptive implant in situ is not well known, researchers have demonstrated that medication abortion initiated at the same time as contraceptive implant insertion does not influence success of the medication abortion.9

Related article:

2016 Update on contraception

For women with desired intrauterine pregnancies, remove the device as soon as feasible and counsel the woman that there is no known teratogenic risk associated with the contraceptive implant.

Read CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CASE Patient requests device removal to attempt conception

A 30-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for contraceptive implant removal because she would like to have another child. The device was placed 30 months ago in the patient’s left arm. The insertion note in the patient’s medical record is unremarkable, and standard insertion technique was used. On physical examination, you cannot palpate the device.

What is your next course of action?

Nonpalpable implants, particularly if removal is desired, present a significant clinical challenge. Do not attempt removing a nonpalpable implant before trying to locate the device through past medical records or radiography. Records that describe the original insertion, particularly the location and type of device, are helpful.

Related article:

2015 Update on contraception

Appropriate imaging assistance. Ultrasonography with a high frequency linear array transducer (10 MHz or greater) may allow an experienced radiologist to identify the implant—including earlier versions without barium (Implanon) and later ones with barium (Nexplanon). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography scan, or plain x-ray also can be used to detect a barium-containing device; MRI can be used to locate a non−barium-containing implant.

Carry out removal using ultrasonographic guidance. If a deep insertion is felt to be close to a neurovascular bundle, device removal should be carried out in an operating room by a surgeon familiar with the anatomy of the upper arm.

When an implant cannot be located despite radiography. This is an infrequent occurrence. Merck, the manufacturer of the etonorgestrel implant, provides advice and support in this circumstance. (Visit https://www.merckconnect.com/nexplanon/over view.html.)

Recently, published case reports detail episodes of implants inserted into the venous system with migration to the heart or lungs.10 While this phenomenon is considered rare, the manufacturer has recommended that insertion of the contraceptive implant avoid the sulcus between the biceps and triceps muscles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

The use of long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods has shown a steady increase in the United States. The major factors for increasing acceptance include high efficacy, ease of use, and an acceptable adverse effect profile. Since these methods require placement under the skin (implantable device) or into the uterus (intrauterine devices [IUDs]), unique management issues arise during their usage. Recently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a committee opinion addressing several of these clinical challenges—among them: pain with insertion, what to do when the IUD strings are not visualized, and the plan of action for a nonpalpable IUD or contraceptive implant.1 In this article we present 7 cases, and successful management approaches, that reflect ACOG’s recent recommendations and our extensive clinical experience.

Read the first CHALLENGE: Pain with IUD insertion

CHALLENGE 1: Pain with IUD insertion

CASE First-time, nulliparous IUD user apprehensive about insertion pain

A 21-year-old woman (G0) presents for placement of a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD for contraception and treatment of dysmenorrhea. Her medical and surgical histories are unremarkable. She has heard that IUD insertion “is more painful if you haven’t had a baby yet” and she asks what treatments are available to aid in pain relief.

What can you offer her?

A number of approaches have been used to reduce IUD insertion pain, including:

- placing lidocaine gel into or on the cervix

- lidocaine paracervical block

- preinsertion use of misoprostol or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Authors of a recent Cochrane review2 indicated that none of these approaches were particularly effective at reducing insertion pain for nulliparous women. Naproxen sodium 550 mg or tramadol 50 mg taken 1 hour prior to IUD insertion have been found to decrease IUD insertion pain in multiparous patients.3 Misoprostol, apart from being ineffective in reducing insertion pain, also requires use for a number of hours before insertion and can cause painful uterine cramping, upset stomach, and diarrhea.2 Some studies do suggest that use of a paracervical block does reduce the pain associated with tenaculum placement but not the IUD insertion itself.

Related article:

Benefit of self-administered vaginal lidocaine gel in IUD placement

A reasonable pain management strategy for nulliparous patients. Given these data, there is not an evidence-based IUD insertion pain management strategy that can be used for the nulliparous case patient. A practical approach for nulliparous patients is to offer naproxen sodium or tramadol, which have been found to be beneficial in multiparous patients, to a nulliparous patient. Additionally, lidocaine gel applied to the cervix or tenaculum-site injection can be considered for tenaculum-associated pain, although it does not appear to help significantly with IUD insertion pain. Misoprostol should be avoided as it does not alleviate the pain of insertion and it can cause bothersome adverse effects.

Read CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CHALLENGE 2: IUD strings not visualized

CASE No strings palpated 6 weeks after postpartum IUD placement

A 26-year-old woman (G2P2) presents to your office for a postpartum visit 6 weeks after an uncomplicated cesarean delivery at term. She had requested that a 52-mg levonorgestrel IUD be placed at the time of delivery, and the delivery report describes an uneventful placement. The patient has not been able to feel the IUD strings using her fingers and you do not find them on examination. She does not remember the IUD falling out.

What are the next steps in her management?

Failure to palpate the IUD strings by the user or failure to visualize the strings is a fairly common occurrence. This is especially true when an IUD is placed immediatelypostpartum, as in this patient’s case.

When the strings cannot be palpated, it is important to exclude pregnancy and recommend a form of backup contraception, such as condoms and emergency contraception if appropriate, until evaluation can be completed.

Steps to locate a device. In the office setting, the strings often can be located by inserting a cytobrush into the endocervical canal to extract them. If that maneuver fails to locate them, an ultrasound should be completed to determine if the device is in the uterus. If the ultrasound does not detect the device in the uterus, obtain an anteroposterior (AP) x-ray encompassing the entire abdomen and pelvis. All IUDs used in the United States are radiopaque and will be observed on x-ray if present. If the IUD is identified, operative removal is indicated.

Related article:

How to identify and localize IUDs on ultrasound

Intraperitoneal location. If an IUD is found in this location, it is usually the result of a perforation that occurred at the time of insertion. In general, the device can be removed via laparoscopy. Occasionally, laparotomy is needed if there is significant pelvic infection, possible bowel perforation, or if there is an inability to locate the device at laparoscopy.4 The copper IUD is more inflammatory than the levonorgestrel IUDs.

Abdominal location. No matter the IUD type, operative removal of intra-abdominal IUDs should take place expeditiously after they are discovered.

In the case of expulsion. If the IUD is not seen on x-ray, expulsion is the likely cause. Expulsion tends to be more common among5:

- parous users

- those younger than age 20

- placements that immediately follow a delivery or second-trimester abortion.

Nulliparity and type of device are not associated with increased risk of expulsion.

Read CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CHALLENGE 3: Difficult IUD removal

CASE Strings not palpated in a patient with history of LEEP

A 37-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office for IUD removal. She underwent a loop electrosurgical excision procedure 2 years ago for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) 2 and since then has not been able to feel the IUD strings. On pelvic examination, you do not palpate or visualize the IUD strings after speculum placement.

How can you achieve IUD removal for your patient?

When a patient requests that her IUD be removed, but the strings are not visible and the woman is not pregnant, employ ultrasonography to confirm the IUD remains intrauterine and to rule out expulsion or perforation.

Employ alligator forceps or an IUD hook. Once intrauterine position is confirmed, use an alligator forceps of suitable length and with a small diameter to extract the device (FIGURE 1). It is useful to utilize ultrasonography for guidance during the removal procedure. The alligator forceps will grasp both the IUD device itself and IUD strings well, so either can be targeted during removal.

A second useful tool for IUD removal is an IUD hook (FIGURE 2). In a similar way that a curette is used for endometrial sampling, IUD hooks can be used to drag the IUD from the uterus.

Anesthesia is not usually necessary for IUD removal with alligator forceps or an IUD hook, although it may be appropriate in select patients. Data are limited with regard to the utility of paracervical blocks in this situation.

Related article:

Surgical removal of malpositioned IUDs

Hysteroscopy is an option. If removal with an alligator forceps or IUD hook is unsuccessful, or if preferred by the clinician, hysteroscopic-guided removal is a management option. Hysteroscopic removal may be required if the IUD has become embedded in the uterine wall.

Read CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CHALLENGE 4: Nonfundal IUD location

CASE Copper IUD found in lower uterine segment

A 31-year-old woman (G1P1) calls your office to report that she thinks her copper IUD strings are longer than before. Office examination confirms that the strings are noticeably longer than is typical. Pelvic ultrasonography shows the copper IUD in the lower uterine segment.

What is the appropriate course of action?

Occasionally, IUDs are noted to be located in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE 3) or cervix. With malposition, users may be experiencing cramping or abnormal bleeding.

Cervical malposition calls for removal. ACOG advises that, regardless of a patient’s presenting symptoms, clinicians should remove IUDs located in the cervix (ie, the stem below the internal os) due to an increased risk of pregnancy and address the woman’s contraceptive needs.

Related article:

STOP relying on 2D ultrasound for IUD localization

Lower-uterine-segment malposition man‑agement less clear. If the patient is symptomatic, remove the device and initiate some form of contraception. If the woman is asymptomatic, the woman should be given the option of having the device removed or left in place. The mechanisms of action of both the copper and levonorgestrel-releasing IUDs suggest that this lower location is unlikely to be associated with a significant decrease in efficacy.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to estimate the risk of pregnancy for a patient whose device is located in the lower uterine segment. Braaten and Goldberg discussed case-controlled data in their 2012 article that suggest malposition may be more important to the efficacy of copper IUDs than of levonorgestrel IUDs.6,7 As unintended pregnancy is an important risk to avoid, ultimately, it is the woman’s decision as to whether she wants removal or continued IUD use.

Read CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CHALLENGE 5: Pregnancy in an IUD user

CASE 3-year copper IUD user with positive pregnancy test

A 25-year-old woman (G3P2) presents to your office because of missed menses and a positive home pregnancy test. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has had a copper IUD in place for 3 years and can feel the strings herself. She has experienced light cramping but no bleeding. Office examination is notable for the IUD stem present at the external cervical os. While the pregnancy is unplanned, the patient desires that it continue.

Should you remove the IUD?

The pregnancy rate among IUD users is less than 1%—a rate that is equivalent to that experienced by women undergoing tubal sterilization. Although there is an overall low risk of pregnancy, a higher proportion of pregnancies among IUD users compared with nonusers are ectopic. Therefore, subsequent management of pregnancy in an IUD user needs to be determined by, using ultrasound, both the location of the pregnancy and whether the IUD is in place.

If an ectopic pregnancy is found, it may be managed medically or surgically with the IUD left in place if desired. If you find an intrauterine pregnancy that is undesired, the IUD can be removed at the time of a surgical abortion or before the initiation of a medical abortion.

If you fail to locate the IUD either before or after the abortion procedure, use an AP x-ray of the entire abdomen and pelvis to determine whether the IUD is in the peritoneal cavity or whether it was likely expelled prior to the pregnancy.

Related article:

In which clinical situations can the use of the 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing IUD (Mirena) and the TCu380A copper-IUD (ParaGard) be extended?

With a desired pregnancy, if the strings are visible, remove the IUD with gentle traction. If the IUD is left in place, the risk of spontaneous abortion is significantly increased. If the strings are not seen, but the device was noted to be in the cervix by ultrasound, remove the device if the stem is below the internal cervical os. For IUDs that are located above the cervix, removal should not be attempted; counsel the patient about the increased risk of spontaneous abortion, infection, and preterm delivery.

Read CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CHALLENGE 6: Pregnancy in an implant user

CASE 3-week implant user with positive pregnancy test

Your 21-year-old patient who received a contraceptive implant 3 weeks earlier now pre‑sents with nausea and abdominal cramping. Her last menstrual period was 6 weeks ago. She has regular cycles that are 28 days in length. Results of urine pregnancy testing are positive. Prior to using the implant, the patient inconsistently used condoms.

How should you counsel your patient?

The rate of pregnancy among implant users is very low; it is estimated at 5 pregnancies per 10,000 implant users per year.8 As in this case, apparent “failures” of the contraceptive implant actually may represent placements that occurred before a very early pregnancy was recognized. Similar to IUDs, the proportion of pregnancies that are ectopic among implant users compared to nonusers may be higher.

With a pregnancy that is ectopic or that is intrauterine and undesired, the device may be left in and use continued after the pregnancy has been terminated. Although the effectiveness of medication abortion with pre-existing contraceptive implant in situ is not well known, researchers have demonstrated that medication abortion initiated at the same time as contraceptive implant insertion does not influence success of the medication abortion.9

Related article:

2016 Update on contraception

For women with desired intrauterine pregnancies, remove the device as soon as feasible and counsel the woman that there is no known teratogenic risk associated with the contraceptive implant.

Read CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CHALLENGE 7: Nonpalpable contraceptive implant

CASE Patient requests device removal to attempt conception

A 30-year-old woman (G2P2) presents for contraceptive implant removal because she would like to have another child. The device was placed 30 months ago in the patient’s left arm. The insertion note in the patient’s medical record is unremarkable, and standard insertion technique was used. On physical examination, you cannot palpate the device.

What is your next course of action?

Nonpalpable implants, particularly if removal is desired, present a significant clinical challenge. Do not attempt removing a nonpalpable implant before trying to locate the device through past medical records or radiography. Records that describe the original insertion, particularly the location and type of device, are helpful.

Related article:

2015 Update on contraception

Appropriate imaging assistance. Ultrasonography with a high frequency linear array transducer (10 MHz or greater) may allow an experienced radiologist to identify the implant—including earlier versions without barium (Implanon) and later ones with barium (Nexplanon). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography scan, or plain x-ray also can be used to detect a barium-containing device; MRI can be used to locate a non−barium-containing implant.

Carry out removal using ultrasonographic guidance. If a deep insertion is felt to be close to a neurovascular bundle, device removal should be carried out in an operating room by a surgeon familiar with the anatomy of the upper arm.

When an implant cannot be located despite radiography. This is an infrequent occurrence. Merck, the manufacturer of the etonorgestrel implant, provides advice and support in this circumstance. (Visit https://www.merckconnect.com/nexplanon/over view.html.)

Recently, published case reports detail episodes of implants inserted into the venous system with migration to the heart or lungs.10 While this phenomenon is considered rare, the manufacturer has recommended that insertion of the contraceptive implant avoid the sulcus between the biceps and triceps muscles.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e69−e77.

- Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Zeng Y, et al. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD007373.

- Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581−584.

- Kho KA, Chamsy DJ. Perforated intraperitoneal intrauterine contraceptive devices: diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):596−601.

- Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Eisenberg DL, Peipert JF. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):718−726.

- Patil E, Bednarek PH. Immediate intrauterine device insertion following surgical abortion. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(4):583−546.

- Braaten and Goldberg. OBG Manag. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):38−46.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397−404.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan YL, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;127(2):306−312.

- Rowlands S, Mansour D, Walling M. Intravascular migration of contraceptive implants: two more cases. Contraception. 2016. In press.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee Opinion No. 672: clinical challenges of long-acting reversible contraceptive methods. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(3):e69−e77.

- Lopez LM, Bernholc A, Zeng Y, et al. Interventions for pain with intrauterine device insertion. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(7):CD007373.

- Karabayirli S, Ayrim AA, Muslu B. Comparison of the analgesic effects of oral tramadol and naproxen sodium on pain relief during IUD insertion. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2012;19(5):581−584.

- Kho KA, Chamsy DJ. Perforated intraperitoneal intrauterine contraceptive devices: diagnosis, management, and clinical outcomes. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21(4):596−601.

- Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, Secura GM, Eisenberg DL, Peipert JF. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(4):718−726.

- Patil E, Bednarek PH. Immediate intrauterine device insertion following surgical abortion. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2015;42(4):583−546.

- Braaten and Goldberg. OBG Manag. Malpositioned IUDs: When you should intervene (and when you should not). OBG Manag. 2012;24(8):38−46.

- Trussell J. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397−404.

- Raymond EG, Weaver MA, Tan YL, et al. Effect of immediate compared with delayed insertion of etonogestrel implants on medical abortion efficacy and repeat pregnancy: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;127(2):306−312.

- Rowlands S, Mansour D, Walling M. Intravascular migration of contraceptive implants: two more cases. Contraception. 2016. In press.

Your teenage patient and contraception: Think “long-acting” first

CASE: Teen patient asks to switch contraceptive methods

A 17-year-old nulliparous woman comes to your clinic for an annual examination. She has no significant health problems, and her examination is normal. She notes that she was started on oral contraceptives (OCs) the year before because of heavy menstrual flow and a desire for birth control but has trouble remembering to take them—though she does usually use condoms. She asks your advice about switching to a different method but indicates that she has lost her health insurance coverage.

What can you offer her as an effective, low-cost contraceptive?

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are especially suited for adolescent and young adult women, for whom daily compliance with a shorter-acting contraceptive may be problematic. Five LARC methods are available in the United States, including a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Liletta), which received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) this year. Like Mirena, Liletta contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel that is released over time. Liletta was introduced by the nonprofit organization Medicines360 and its commercial partner Actavis Pharma in response to evidence that poor women continue to lack access to LARC because of cost or problems with insurance coverage.1

For providers who practice in settings eligible for 340B pricing, Liletta costs $50, a fraction of the cost of alternative intrauterine devices (IUDs). The cost is slightly higher for non-340B providers but is still significantly lower than the cost of other IUDs. For health care practices, the reduced price of Liletta may make it feasible for them to offer LARC to more patients. The reduced pricing also makes Liletta an attractive option for women who choose to pay for the device directly rather than use insurance, such as the patient described above.

Patient experience with Liletta also is key. Not surprisingly, Liletta’s clinical trial found patient satisfaction to be similar to that of Mirena users.2 The failure rate is less than 1%, again comparable to Mirena. The rate of pelvic infection with Liletta use was 0.5%, also comparable to previously published data.3

One difference between Liletta and Mirena is that Liletta carries FDA approval for 3 years of contraceptive efficacy, compared with 5 years for Mirena. In order to make Liletta available to US patients now, Medicines360 decided to apply for 3-year contraceptive labeling while 5- and 7-year efficacy data are being collected. Like Mirena, Liletta is expected to provide excellent contraception for at least 5 years.

How to insert Liletta

- While still pinching the insertion tube, slide the tube through the cervical canal until the upper edge of the flange is approximately 1.5 to 2 cm from the cervix. Do not force the inserter. If necessary, dilate the cervical canal. Release your hold on the tenaculum.

- Hold the insertion tube with the fingers of one hand (Hand A) and the rod with the fingers of the other hand (Hand B).

- Holding the rod in place (Hand B), relax your pinch on the tube and pull the insertion tube back with Hand A to the edge of the second indent of the rod. This will allow the IUS arms to unfold in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE). Wait 10 to 15 seconds for the arms of the IUS to open fully.

- Apply gentle traction with the tenaculum before advancing the IUS. With Hand A still holding the proximal end of the tube, advance both the insertion tube and rod simultaneously up to the uterine fundus. You will feel slight resistance when the IUS is at the fundus. Make sure the flange is touching the cervix when the IUS reaches the uterine fundus. Fundal positioning is important to prevent expulsion.

- Hold the rod still (Hand B) while pulling the insertion tube back with Hand A to the ring of the rod. While holding the inserter tube with Hand A, withdraw the rod from the insertion tube all of the way out to prevent the rod from catching on the knot at the lower end of the IUS. Completely remove the insertion tube.

- Using blunt-tipped sharp scissors, cut the IUS threads perpendicular to the thread length, leaving about 3 cm outside of the cervix. Do not apply tension or pull on the threads when cutting to prevent displacing the IUS. Insertion is now complete.

Source: Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

Skyla is another LARC option for womenseeking an LNG-IUS for contraception. It provides highly effective contraception for at least 3 years through the release of 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel over time. Skyla’s reduced levonorgestrel content, as compared with Mirena and Liletta, means that fewer users will experience amenorrhea (13% vs 25%).

Paragard is a nonhormonal IUD that uses copper for contraceptive efficacy. The device contains a total of 380 mm of copper. Possible mechanisms of action include interference with sperm migration in the uterus and damage to or destruction of ova. It is FDA-approved for at least 10 years of use. The lack of any hormone in Paragard IUDs may make them attractive to women who do not wish to experience amenorrhea.

Nexplanon is a subdermal implant containing 68 mg of etonogestrel; it is approved for at least 3 years of use. It is the only LARC method that does not require a pelvic examination. Providers are required to complete a training course offered by the manufacturer to ensure proper placement and removal technique.

LARC should be a first-line birth control option

The primary indication for LARC is preg-nancy prevention. Because LARC methods are the most effective reversible means to prevent pregnancy—apart from complete abstinence from sexual intercourse—they should be offered as first-line birth control options to patients who do not wish to conceive. The ability to discontinue LARC methods is an attractive option for women who may want to become pregnant in the future, such as the patient in the opening vignette.

Efficacy rates are high

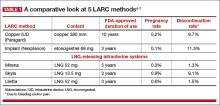

Because LARC methods do not require users to take action daily or prior to intercourse, they carry a risk of pregnancy of less than 1% (TABLE 1)4-7—equal to or better than rates seen with tubal sterilization. In comparison, the OC pill has a typical use contraceptive failure rate of about 8%.

LARC still has a low utilization rate

It is unfortunate that barriers to LARC methods remain in the United States (see, for example, “National organization identifies barriers to LARC,” above). As recently as 2011 to 2013, only 7.2% of US women aged 15 to 44 years used a LARC method.8 Provider inexperience and patient fears surrounding LARC use remain major barriers. In the past, nulliparity and young age were thought to be contraindications to IUD use. Research and experience have demonstrated, however, that IUDs and contraceptive implants are safe for use in young women and those who have not had children.

Cost barriers also have significantly limited the use of LARC methods. Over time, however, these contraceptives have become less costly to patients, and most insurance providers routinely cover LARC devices and insertion fees. The contraceptive mandate of the Affordable Care Act ensures coverage of contraception, including LARC, for interested women. These trends suggest continued improvement in women’s access to LARC.

National organization identifies barriers to LARC

In 2014, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), with support from Bayer Healthcare, organized a meeting of key opinion leaders to discuss ways to eliminate barriers to the most effective contraceptive methods, better known as long-acting reversible contraception (LARC). The resultant issue brief, Women’s Health: Approaches to improving unintended pregnancy rates in the United States, identified a number of key barriers:

- Financial and logistical obstacles. The consensus attendees agreed that LARC methods should be offered to all women not planning a pregnancy in the next 2 years, but acknowledged that operational or administrative process issues sometimes interfere with this goal. One of the most prominent of these issues was the lack of opportunity for same-day insertion of LARC. Other issues included the cost to stock LARC methods, a lack of understanding of billing and reimbursement for LARC, reimbursement policies that prohibit billing for the visit and placement on the same day, and an overabundance of paperwork.

- Timing of the contraceptive counseling session. Many women fail to return for the 6-week postpartum visit—the visit typically set aside for counseling about contraception.

- Lack of a quality measure that would “motivate change in clinical practice.”1 One option: Treat family planning as a “vital sign” that needs to be addressed during the annual visit. “This would lead to stronger evidence for effecting change,” the report notes.1

- Lack of adequate communication skills by the provider. According to the NCQA report, “There are strong positive relationships between a health care team member’s communication skills and a patient’s willingness to follow through with medical recommendations.”1 The establishment of a “current counseling approach” that emphasizes the efficiency and effectiveness of LARC methods as well as the tremendous impact an unintended pregnancy would have on a woman’s whole life course would help improve provider-patient communication and increase the likelihood of LARC methods being utilized.1

- Lack of receptivity among some patients. For some women, the person delivering the message is as important as the message itself, depending on social and cultural norms. Sensitivity of health care providers to these nuances of communication can help enhance patient receptivity to the key message. As the NCQA report notes, “Physicians and the health care system are not always the most trusted source of information, and understanding disparities in contraception care will be important in changing patient behavior.”1

- Basic issues such as cost and access to care.1 Not all women are covered by insurance, particularly in states that opted against expanding access to Medicaid. For these women, the cost of LARC methods and insertion may be prohibitive.

Reference

Noncontraceptive benefits include reduced bleeding

The 3 LNG-IUS methods and the subdermal implant offer several benefits beyond contraception. Because of their progestin content, these methods reduce or even eliminate menses. This benefit can be very helpful for women who experience heavy menstrual periods and the consequent risk of anemia. Because of reduced menstrual flow, users of hormonal LARC methods also commonly experience less cramping associated with menses.

Women with endometriosis often benefit from hormonal LARC methods, as the disease is suppressed by the progestin component. Users of IUDs also have a reduced risk of endometrial cancer.

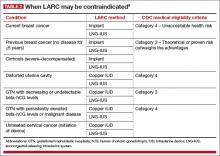

Contraindications to LARC

There are few contraindications to LARC methods, making them an appropriate choice for most women. The US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2010, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contain guidelines that are based on the best available evidence.9 Contraceptive methods that are labeled as Category 1 or 2 are not contraindicated for most women. Methods that fall into Category 3 (theoretical or proven risks outweigh the advantages) or Category 4 (unacceptable health risk) are contraindicated (TABLE 2).9

IUDs once were thought to expose women to an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, but this fear has long been disproven. Screening for chlamydia can be performed at the time of placement, as recommended annually for women younger than 25 years. Unless there is concern for active cervical or uterine infection, there is no need to delay insertion of an IUD while awaiting test results. In most cases, women found to have positive cultures after insertion can be treated successfully without IUD removal.

Main adverse effect is altered bleeding patterns

Adverse effects vary depending on the method being used. All LARC methods may affect menstrual patterns. For example, clinical trials involving the copper IUD indicate that abnormal heavy bleeding may lead to discontinuation in up to 10% of users.5,10 Amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea is uncommon with this method and rarely leads to discontinuation. For example, in one trial involving more than 900 women using a copper IUD for up to 5 years, there were no discontinuations due to amenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea may arise, but data from clinical trials indicate that its frequency decreases over time. In one trial, the frequency of any menstrual pain decreased from about 9% of users to 5% after 8 months or more of use.

The LNG-IUS also can be associated with abnormal uterine bleeding. In contrast to the copper IUD, LNG devices tend to reduce menstrual bleeding and can be unpredictable. Clinical trials involving the 5-year 52-mg LNG-IUS indicate that bleeding decreases over time, with as many as 70% of users developing amenorrhea or oligomenorrhea.5,11 However, some women using an LNG-IUS experience heavy bleeding— although the frequency of such bleeding tends to be substantially less than that experienced by copper IUD users.7

A lack of comparative trials makes it unclear whether the newer 3-year LNG-IUS devices are associated with a significantly altered bleeding pattern. Noncomparative data from the package insert for Skyla suggest that women using it may have a higher frequency of heavy menstrual bleeding and less amenorrhea than users of the 5-year device.6

Data from a 3-year clinical trial of the newest 52-mg LNG-IUS (Liletta) indicate that bleeding and dysmenorrhea led to discontinuation 1% to 2% of the time.2

Although the concentration of progestincirculating systemically is low with the various LNG-IUS devices, some women may experience symptoms such as mood swings, headaches, acne, and breast tenderness.

Expulsions during the first year of use of the copper IUD and the 3 LNG-IUS devices range from 2% to 10%, with the higher rates associated with immediate postpartum insertion.5

Uterine perforation has been reported in about 1 of every 1,000 insertions. Other adverse events are uncommon.

Clinical trials indicate that about 11% of implant users will discontinue the method due to bleeding abnormalities.12 About 25% to 30% of users will experience heavy or prolonged bleeding, while up to 33% will experience infrequent bleeding or amenorrhea. About 50% of implant users will experience improved bleeding patterns over time.

Other reasons for discontinuation of implant use in a very small percentage of users include emotional lability, weight gain, acne, and headaches.4 Complications due to insertion and removal are rare and include pain, bleeding, and hematoma formation.

Public health impact of LARC methods

An important question in regard to LARC use is: How do we best provide safe and effective contraception for teens and young adult women? There is increasing evidence that, with appropriate counseling and the removal of cost barriers, LARC methods can have a significant public health impact in this population.

The Contraceptive CHOICE Project, a cohort study in a teenage population of women in the St. Louis, Missouri, area, achieved increased utilization of LARC methods and significantly lower rates of pregnancy, birth, and abortion.13 Investigators proactively counseled young women about the advantages of LARC methods and offered them free of charge. As a result, 72% of women in the study chose an IUD or implant as their method of contraception. Pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates among participants were 34.0, 19.4, and 9.7 per 1,000 teens, respectively. By comparison, national statistics during the same time frame for pregnancy, birth, and abortion were 158.5, 94.0, and 41.5 per 1,000 US teens, respectively.13

A similar project in Colorado received $23.6 million in 2009 from an outside donor to make LARC methods more affordable to patients in family planning clinics in the state.14 Between 2009 and 2014, 30,000 contraceptive implants or IUDs were made available at low or no cost to low-income women attending 68 family planning clinics statewide. The use of these methods at participating clinics quadrupled. Further, the teen birth rate declined by 40% between 2009 and 2013—from 37 to 22 births per 1,000 teens.14 Seventy-five percent of this decline was attributable to increased use of these methods. The teen abortion rate declined by 35% in the same time frame.

In 2014, the Colorado governor’s office indicated that the state had saved $42.5 million in health care expenditures associated with teen births. It was estimated that, for every dollar spent on contraceptives, the state saved $5.68 in Medicaid costs. However, a bipartisan bill to continue funding the project has failed so far in 2015 due to concerns among some legislators that these methods—particularly the IUDs—are abortifacients. The reduced cost of the 3-year LNG-IUS (Liletta) and recent guidance from the US Department of Health and Human Services mandating that at least 1 form of contraception in each of the FDA-approved categories must be covered by insurers may help to overcome this barrier.

CASE: Resolved

You counsel the patient about the value of each LARC method, letting her know that they are all highly effective in the prevention of pregnancy. You also let her know how each method would affect her menstrual cycle and acknowledge that she may have a preference for whether the contraceptive is placed in her uterus or under the skin of her arm. She chooses the contraceptive implant, which you insert during the same visit. At a follow-up visit 6 weeks later, she reports satisfaction with the method.

Share your thoughts on this article! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

1. Dehlendorf C, Rodriguez MI, Levy K, Borrero S, Steinauer J.Disparities in family planning. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(3):214–220.

2. Eisenberg DL, Schreiber CA, Turok DK, et al. Three-year efficacy and safety of a new 52-mg levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system. Contraception. 2015;92(1):10–16.

3. Sufrin C, Postlethwaite D, Armstrong MA, et al. Neisseria gonorrhea and Chlamydia trachomatis screening at intrauterine device insertion and pelvic inflammatory disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(6):1314–1321.

4. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives—intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(3):705–719.

5. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Practice Bulletin No. 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(1):184–196.

6. Skyla [package insert]. Bayer Healthcare, Wayne, NJ; 2013.

7. Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

8. Branum AM, Jones J. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: NCHS Data Brief No. 188: Trends in Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Use Among US Women Aged 15–44. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db188.htm. Published February 2015. Accessed August 14, 2015.

9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59(RR4):1–86.

10. Andersson K, Odlind VL, Rybo G. Levonorgestrel-releasing and copper-releasing (Nova T) IUDs during five years of use; a randomized comparative trial. Contraception. 1994;49(1):56–72.

11. Sivin I, Stern J, Diaz J, et al. Two years of intrauterine contraception with levonorgestrel and copper: a randomized comparison of the TCu 380Ag and levonorgestrel 20 mcg/day devices. Contraception. 1987;35(3):245–255.

12. Mansour F, Korver T, Marintcheva-Petrova M, Fraser IS. The effects of Implanon on menstrual bleeding patterns. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2008;13(suppl 1):13–28.

13. Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. Provision of no-cost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1316–1323.

14. Tavernise S. Colorado’s effort against teenage pregnancies is a startling success. New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/06/science/colorados-push-against-teenage-pregnancies-is-a-startling-success.html. Published July 6, 2015. Accessed August 17, 2015.

CASE: Teen patient asks to switch contraceptive methods

A 17-year-old nulliparous woman comes to your clinic for an annual examination. She has no significant health problems, and her examination is normal. She notes that she was started on oral contraceptives (OCs) the year before because of heavy menstrual flow and a desire for birth control but has trouble remembering to take them—though she does usually use condoms. She asks your advice about switching to a different method but indicates that she has lost her health insurance coverage.

What can you offer her as an effective, low-cost contraceptive?

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are especially suited for adolescent and young adult women, for whom daily compliance with a shorter-acting contraceptive may be problematic. Five LARC methods are available in the United States, including a new levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS; Liletta), which received approval from the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) this year. Like Mirena, Liletta contains 52 mg of levonorgestrel that is released over time. Liletta was introduced by the nonprofit organization Medicines360 and its commercial partner Actavis Pharma in response to evidence that poor women continue to lack access to LARC because of cost or problems with insurance coverage.1

For providers who practice in settings eligible for 340B pricing, Liletta costs $50, a fraction of the cost of alternative intrauterine devices (IUDs). The cost is slightly higher for non-340B providers but is still significantly lower than the cost of other IUDs. For health care practices, the reduced price of Liletta may make it feasible for them to offer LARC to more patients. The reduced pricing also makes Liletta an attractive option for women who choose to pay for the device directly rather than use insurance, such as the patient described above.

Patient experience with Liletta also is key. Not surprisingly, Liletta’s clinical trial found patient satisfaction to be similar to that of Mirena users.2 The failure rate is less than 1%, again comparable to Mirena. The rate of pelvic infection with Liletta use was 0.5%, also comparable to previously published data.3

One difference between Liletta and Mirena is that Liletta carries FDA approval for 3 years of contraceptive efficacy, compared with 5 years for Mirena. In order to make Liletta available to US patients now, Medicines360 decided to apply for 3-year contraceptive labeling while 5- and 7-year efficacy data are being collected. Like Mirena, Liletta is expected to provide excellent contraception for at least 5 years.

How to insert Liletta

- While still pinching the insertion tube, slide the tube through the cervical canal until the upper edge of the flange is approximately 1.5 to 2 cm from the cervix. Do not force the inserter. If necessary, dilate the cervical canal. Release your hold on the tenaculum.

- Hold the insertion tube with the fingers of one hand (Hand A) and the rod with the fingers of the other hand (Hand B).

- Holding the rod in place (Hand B), relax your pinch on the tube and pull the insertion tube back with Hand A to the edge of the second indent of the rod. This will allow the IUS arms to unfold in the lower uterine segment (FIGURE). Wait 10 to 15 seconds for the arms of the IUS to open fully.

- Apply gentle traction with the tenaculum before advancing the IUS. With Hand A still holding the proximal end of the tube, advance both the insertion tube and rod simultaneously up to the uterine fundus. You will feel slight resistance when the IUS is at the fundus. Make sure the flange is touching the cervix when the IUS reaches the uterine fundus. Fundal positioning is important to prevent expulsion.

- Hold the rod still (Hand B) while pulling the insertion tube back with Hand A to the ring of the rod. While holding the inserter tube with Hand A, withdraw the rod from the insertion tube all of the way out to prevent the rod from catching on the knot at the lower end of the IUS. Completely remove the insertion tube.

- Using blunt-tipped sharp scissors, cut the IUS threads perpendicular to the thread length, leaving about 3 cm outside of the cervix. Do not apply tension or pull on the threads when cutting to prevent displacing the IUS. Insertion is now complete.

Source: Liletta [package insert]. Actavis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ; 2015.

Skyla is another LARC option for womenseeking an LNG-IUS for contraception. It provides highly effective contraception for at least 3 years through the release of 13.5 mg of levonorgestrel over time. Skyla’s reduced levonorgestrel content, as compared with Mirena and Liletta, means that fewer users will experience amenorrhea (13% vs 25%).

Paragard is a nonhormonal IUD that uses copper for contraceptive efficacy. The device contains a total of 380 mm of copper. Possible mechanisms of action include interference with sperm migration in the uterus and damage to or destruction of ova. It is FDA-approved for at least 10 years of use. The lack of any hormone in Paragard IUDs may make them attractive to women who do not wish to experience amenorrhea.

Nexplanon is a subdermal implant containing 68 mg of etonogestrel; it is approved for at least 3 years of use. It is the only LARC method that does not require a pelvic examination. Providers are required to complete a training course offered by the manufacturer to ensure proper placement and removal technique.

LARC should be a first-line birth control option